Abstract

Investigation of the non-equilibrium dynamics after an impulsive impact provides insights into couplings among various excitations. A two-temperature model (TTM) is often a starting point to understand the coupled dynamics of electrons and lattice vibrations: the optical pulse primarily raises the electronic temperature Tel while leaving the lattice temperature Tl low; subsequently the hot electrons heat up the lattice until Tel = Tl is reached. This temporal hierarchy owes to the assumption that the electron-electron scattering rate is much larger than the electron-phonon scattering rate. We report herein that the TTM scheme is seriously invalidated in semimetal graphite. Time-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TrPES) of graphite reveals that fingerprints of coupled optical phonons (COPs) occur from the initial moments where Tel is still not definable. Our study shows that ultrafast-and-efficient phonon generations occur beyond the TTM scheme, presumably associated to the long duration of the non-thermal electrons in graphite.

One of the most interesting observation in the ultrafast dynamics of graphite is that Tel in the sub-picosecond temporal region stays somewhat low even though irradiated with an intense femtosecond optical pulse.1 This led to the picture that the electronic energy is quasi-instantaneously transferred to the COPs through strong electron-phonon couplings1 based on the TTM scheme.2,3,4 However, electron-phonon coupling constant is reported to be moderately small in graphite,6 making the mechanism of the ultrafast COP generation elusive. Subsequent studies also suggest the nearly instantaneous COP generation coupled to the electron dynamics,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 which is considered to affect ballistic transports at high fields.15,16,17,18,19 Nevertheless, direct observation of the electron distribution in the transient is limited,9,12,20,21 and moreover, simultaneous detection of the electron distribution and the phonons in the transient has been beyond reach. TrPES [Fig. 1(a)] is one of the most powerful tools to investigate the dynamics of the electrons, since it can provide information of the transient electron distributions in a wide energy range across the Fermi level (EF).4,20,21,22,23,24 Furthermore, Liu et al.5 recently reported that fingerprints of COPs occur in the photoemission spectra of graphite, as we shall explain below. Therefore, it became possible to monitor simultaneously the electron distribution and the fingerprints of COPs during the ultrafast dynamics of graphite by TrPES.

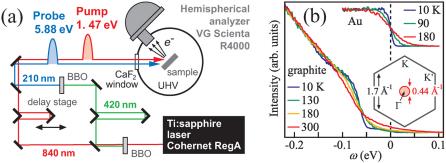

Figure 1. TrPES system.

(a) A schematic of the TrPES system. (b) Spectra of graphite recorded in normal-emission geometry. The increase of the intensity at EF with increasing T is due to the increased population of the COPs.5 Inset of (b) shows the surface Brillouin zone of graphite, and the area probed in the normal-emission geometry is indicated by a circle.

The fingerprints of COPs show up in the spectra recorded in a normal-emission geometry,5 that is, when we detect the photoelectrons around Γ of the surface Brillouin zone of graphite [inset in Fig. 1(b)]. Since there are no bands around Γ in the vicinity of EF, the signal consists of photoelectrons around K (K′) indirectly scattered into the vicinity of Γ mainly by phonons. As we shall see later, signals of direct photoexcitations around the K (K′) point indeed occur in the TrPES spectra recorded in the normal-emission geometry. A gap-like feature of ∼70 meV occurs in the spectra near-EF at low T [Fig. 1(b)], since phonon absorption process is quenched and phonon emission (energyloss) process dominates. With increasing T, phonon absorption process is increased, and the spectral weight tails into higher energies resulting in an increase of the spectral intensity at EF [Fig. 1(b)]. This is similar to anti-Stokes lines in Raman spectra gaining stronger intensity at higher temperatures. Thus, we utilize the spectral intensity at EF in TrPES as a measure of the number of COPs in the transient. The optical phonons monitored herein are assigned to the 67-meV out-of-plane and the ∼150-meV in-plane modes.5

Results

TrPES spectra

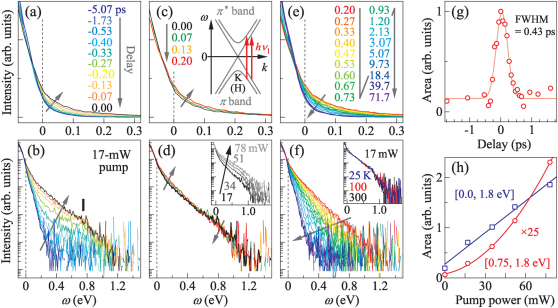

Figure 2(a–f) show TrPES spectra of graphite, I(ω, t), recorded under a pump power p = 17 mW (a fluence of ∼14 µJ/cm−2) at room temperature. A movie file is provided in Supplementary Information. Overall, we observe that the electrons are pumped from the occupied side to the unoccupied side and subsequent recovery dynamics lasting over several tens of picoseconds: at t ≤ 0 ps, the spectral intensity I(ω, t) is increased in the unoccupied side; at 0≤t≤0.20 ps, I(ω, t) at ω ∼ 0.75 eV is decreased, whereas that at ω ∼ 0 eV is increased; at t≥0.20 ps, I(ω, t) in the unoccupied side is decreased. Here, t = 0 ps has been determined utilizing the fast response of ∼20 fs observed at ω > 0.8 eV,12 and the time resolution [full width at half the maximum (FWHM)] is estimated to be Δt = 0.43 ps, see Fig. 2(g).

Figure 2. TrPES of graphite.

Spectra recorded at 17-mW pump at t ≤ 0 ps (a, b), 0 ≤ t ≤ 0.2 ps (c, d), and t ≥ 0.2 ps (e, f). Here, (b, d, f) are semi-logarithmic plots of (a, b, c), respectively. Insets in (d) and (f) show spectra at t = 0 ps recorded at various pump powers and temperatures, respectively. (g) Spectral weight between 0.8 – 1.0 eV as a function of t overlaid with a Gaussian. (h) Spectral weight under 0.75 – 1.8 eV (above the cutoff; circle) and under 0.0 – 1.8 eV (in the unoccupied side; square) at t = 0 ps as a function of pump power overlaid with first and second order polynomial functions, respectively. The schematic in (c) shows direct excitations from the π bands to the π* bands.

We observe a plateau feature in the unoccupied side during the pump [Fig. 2(b) and the movie file in Supplementary Information], which is a hallmark of a non-thermal electron distribution.22 The plateau turns over into an exponential tailing at t ≳ 0.20 ps [Fig. 2(f)], indicating that the electrons are distributed according to the Fermi-Dirac function. That is, electronic thermalization occurs at τe ∼ 0.2 ps so that Tel becomes definable thereafter. In metallic materials, typical time scale for electronic thermalization is considered to be τe ∼ 10 fs or less,2 and if Δt ≫ τe, one would not expect to observe a non-thermal distribution of the hot electrons. In fact, in the TrPES study of a metallic Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ,4 Perfetti et al. observed with Δt ∼ 90 fs that the spectra mostly obey Fermi-Dirac statistics even at t ∼ 0 ps. The smallness of 1/τe in graphite can be attributed to the semimetallic band structure: Since electronic states near EF occur only around K(K′) points of the surface Brillouin zone, the available phase space for electron-electron scatterings becomes vanishingly small in approaching EF particularly after the initial avalanche of the hot electrons towards EF. This can act as a bottleneck for the non-thermal electrons to relax into the thermal (Fermi-Dirac) distribution.

The plateau observed just after the pump extends up to a cutoff at ω ∼ 0.75 eV, as indicated by a bar in Fig. 2(b). This cutoff can be understood as a fingerprint of direct photoexcitations occurring around the K(K′) point: since the π- and π*-bands are nearly symmetric about EF as shown in the schematic in Fig. 2, direct excitations are dominated by the transitions from ω = −hν1/2 to +hν1/2, and therefore, the cutoff energy can be identified to ω ∼ hν1/2 = 0.75 eV. Note that such a fingerprint of direct excitations would not be detected if τe ≪ Δt. Therefore, the ∼0.75-eV cutoff strengthens the conclusion that the duration of the non-thermal electron distribution is detected in the present study.

With increasing p, the cutoff is blurred [inset in Fig. 2(d)], so that the unoccupied side of the spectra becomes featureless and the line shape becomes similar to the TrPES spectra of graphite reported previously.21 The intensity above the cutoff at t = 0 ps grows quadratically with p while the intensity in the unoccupied side grows linearly with p [Fig. 2(h)]. The latter indicates that the number of electrons excited by the pump is proportional to p at least up to 78 mW, whereas the former indicates that the excited electrons are further scattered above the cutoff by other excitations such as the hot electrons themselves or hot phonons, since such scatterings occur roughly proportional to the square of the population of the excited particles. The intensity and the sharpness of the cutoff are almost independent of T [inset of Fig. 2(f)], indicating that the blurring of the cutoff is not related to the thermally populated excitations in the initial state.

We now turn to the variation of the spectral weight around EF, which serves as the fingerprints of COPs in the transient, as explained previously. One can see that the variation starts from the beginning of the transient in accord with the reports of the nearly instantaneous generation of the COPs in graphite.8,11,14 Our findings therefore show that the ultrafast COP generation takes place from the temporal region where the hot electrons are not thermalized [see, Fig. 2(a) and the movie file in Supplementary Information]. After t ∼ 0.2 ps, the intensity at EF starts to decrease, see Fig. 2(e), indicating that the COP generation is mosltly accomplished within t ≲ 0.2 ps. The results are in strong contrast to the TTM scheme, where COPs are assumed to be cool at the beginning and then gradually heated up by the electrons that are thermalized.

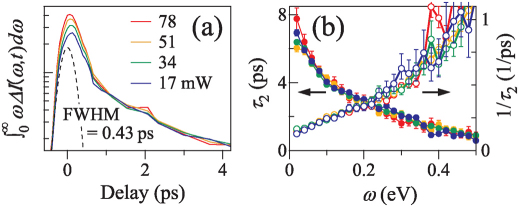

Analysis of TrPES spectra

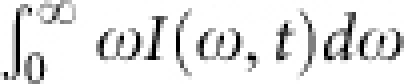

First, we investigate how the total electronic energy dissipates with time. As I(ω, t) reflects the occupied density of states (DOS),  is a measure of the excess electronic energy, and we plot this as a function of t in Fig. 3(a). Here, ΔI(ω, t) = I(ω, t) − I(ω, −5 ps). The energy dissipation occurs with two time scales having distinct pump-power dependences: at t ≲ 1 ps, the energy dissipation rate positively depends on p, whereas at t ≳ 1 ps, it is independent of p. The fast dynamics at t ≲ 1 ps is attributed to the net energy flow from the hot electrons to the hot COPs through electron-phonon scatterings, since this channel is increased quadratically with p due to the increased populations of the hot electrons and hot COPs. Note that the scatterings among the hot electrons cannot account for the loss of the electronic energy.25 At t ∼ 1 ps, the electrons and COPs reach quasi-equilibrium (Tel = TCOP) after a sufficient number of scatterings, and the electron-COP composite dissipates its energy to the heat bath such as acoustic phonons,26 and hence the p-independent energy dissipation at t ≳ 1 ps.

is a measure of the excess electronic energy, and we plot this as a function of t in Fig. 3(a). Here, ΔI(ω, t) = I(ω, t) − I(ω, −5 ps). The energy dissipation occurs with two time scales having distinct pump-power dependences: at t ≲ 1 ps, the energy dissipation rate positively depends on p, whereas at t ≳ 1 ps, it is independent of p. The fast dynamics at t ≲ 1 ps is attributed to the net energy flow from the hot electrons to the hot COPs through electron-phonon scatterings, since this channel is increased quadratically with p due to the increased populations of the hot electrons and hot COPs. Note that the scatterings among the hot electrons cannot account for the loss of the electronic energy.25 At t ∼ 1 ps, the electrons and COPs reach quasi-equilibrium (Tel = TCOP) after a sufficient number of scatterings, and the electron-COP composite dissipates its energy to the heat bath such as acoustic phonons,26 and hence the p-independent energy dissipation at t ≳ 1 ps.

Figure 3. Decay rates.

(a) Electronic energy (see text) vs t for various pump powers. Each curve has an arbitrary offset. Dashed line represents the time resolution. (b) The spectra of decay time and decay rate (left and right axes, respectively) of the slow component.

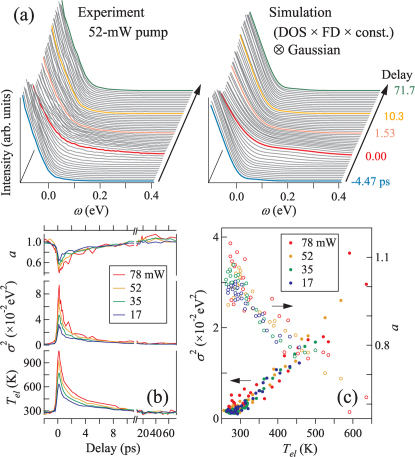

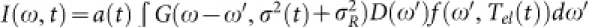

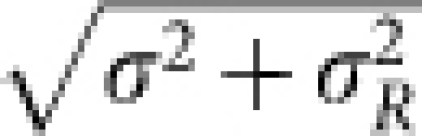

Further analysis of the spectra also supports that the recovery dynamics at t ≳ 1 ps is characterized by Tel = TCOP and decay rates independent of p. First, we derive the decay-rate spectrum for the slower component 1/τ2(ω), which is obtained by fitting I(ω, t) at each energy with a double exponential function (Supplementary Information). As shown in Fig. 3(b), 1/τ2(ω) is independent of p and is quasi-linear to ω at ω ≲ 0.3 eV. Second, we quantify the spectral shape by simulating the spectrum as  . Here,

. Here,  is a Gaussian with FWHM of

is a Gaussian with FWHM of  , f(ω, Tel) is the Fermi-Dirac function, a(t) is a scaling factor, and D(ω) is a DOS. The Gaussian broadening accounts for the spectral weight accumulating from lower energies, so that σ2 becomes a measure of the number of the COPs in the transient. The spectra are nicely reproduced throughout the transient [Fig. 4(a) and Supplementary Information], and the fitting parameters are summarized in Fig. 4(b) and (c). One can see that σ2 and a for t > 1.0 ps scales with Tel and does not explicitly depend on p. This indicates that the number of the COPs at t > 1.0 ps is a function of Tel, i.e., TCOP = Tel, and that the spectral shape at t > 1.0 ps is determined only by Tel, which is the temperature of the electron-COP composite.

, f(ω, Tel) is the Fermi-Dirac function, a(t) is a scaling factor, and D(ω) is a DOS. The Gaussian broadening accounts for the spectral weight accumulating from lower energies, so that σ2 becomes a measure of the number of the COPs in the transient. The spectra are nicely reproduced throughout the transient [Fig. 4(a) and Supplementary Information], and the fitting parameters are summarized in Fig. 4(b) and (c). One can see that σ2 and a for t > 1.0 ps scales with Tel and does not explicitly depend on p. This indicates that the number of the COPs at t > 1.0 ps is a function of Tel, i.e., TCOP = Tel, and that the spectral shape at t > 1.0 ps is determined only by Tel, which is the temperature of the electron-COP composite.

Figure 4. Optical-phonon broadenings during the transient.

(a) TrPES spectra recorded under 52-mW pump (left) and the simulated spectra (right). (b) Fitting parameters. (c) A plot of the fitting parameters σ2 and a with respect to Tel for t > 1.0 ps.

Discussion

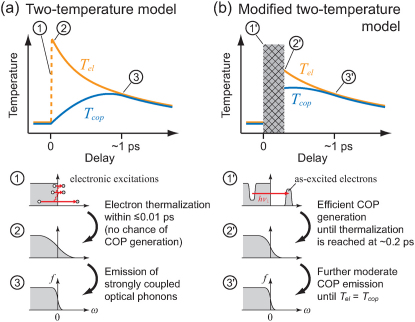

We experimentally find that the electronic distribution is non-thermal at t ≲ 0.2 ps, and also find evidence that the COP generation is mostly accomplished within this initial temporal region. This strongly indicates that the mechanism of the ultrafast COP generation is beyond the TTM scheme, see Fig. 5. Since the duration of the non-thermal electron distribution is longer than that in the TTM scheme, the high-energy electrons, which is considered to be favorable for generating high-energy COPs,27 indeed have more chance to generate COPs before they degrade into low-energy thermalized electrons. Therefore, not only the largeness of the electron-phonon couplings but also the long durations of the non-thermal electron distribution may be crucial for understanding the ultrafast-and-efficient generation of the COPs in graphite. It is interesting to note that a break-down of TTM was also suggested in YBa2Cu3O7–δ,28 in which the DOS becomes vanishingly small around EF in the d-wave superconducting state, similar to the case for graphite. Therefore, coupled dynamics directly involving the non-thermal electrons may be sought in materials that have vanishingly small DOS around EF, for example in neutral graphene,29 in nodal superconductors,28 and on the surface of topological insulators.30 Alternatively, we do not exclude the possibility that the hot COPs and hot electrons are co-generated by the pump, which may be viewed as a counterpart of the breakdown of adiabatic Born-Oppenheimer approximation:31 in as much as the electrons cannot follow the motion of the lattice, COPs are simultaneously generated when the electronic excitation takes place. Whichever the case may be, our study reveals that there is a unique mechanism of ultrafast COP generation where the concept of temperatures is broken.

Figure 5. Two-temperature model (a) and beyond (b).

The top panels show the transient change of Tel and Tcop. Hatched area indicates temporal region where Tel cannot be defined. The lower panels show electron distribution functions (f) at some selected moments. The major difference in the COP-generation mechanism between the two is whether they are generated by the thermal electrons (a) or by the non-thermal electrons (b).

Methods

The TrPES apparatus consists of an amplified Ti:sapphire laser system delivering hν1 = 1.5 eV pulses of 170-fs duration with 250-kHz repetition and a hemispherical analyzer,32 see Fig. 1(a). A portion of the laser is converted into hν4 = 5.9 eV probing pulses using two non-linear crystals, β-BaB2O4 (BBO), and the time delay t from the pump is controlled by a delay stage. The pump and probe pulses are p-polarized and have spot diameters of ∼0.8 and ∼0.3 mm, respectively, at the sample position. The intensity of the probe pulse is minimized to avoid space charge effects. Multi-photon photoemission due to the pump pulse is not observed in the dataset presented herein. EF is referenced to the Fermi cutoff of gold and the energy resolution σR is 11 meV. The base pressure of the photoemission chamber is 1 × 10−10 Torr, and highly-oriented pyrolitic graphite is cleaved in situ.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions Statement Y.I., T. Togashi, K.Y., T.K, M.N., T.S. and S.S. developed the TrPES apparatus. Y.I., T. Togashi, K.Y., M.T. and T. Taniuchi performed the experiments. Y.I. analyzed the data and wrote the paper with S.S. All the authors contributed to discussion.

Supplementary Material

S1_text

S2_Graphite_trPES

Acknowledgments

Y.I. acknowledge support from JSPS KAKENHI (23740256).

References

- Kampfrath T., Perfetti L., Schapper F., Frischkorn C. & Wolf M. Strongly coupled optical phonons in the ultrafast dynamics of the electronic energy and current relaxation in graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 187403 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P. B. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1460–1463 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorson S. D. et al.. Femtosecond room-temperature measurement of the electron-phonon coupling constant λ in metallic superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2172–2175 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti L. et al.. Ultrafast electron relaxation in superconducting Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ by time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 197001 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al.. Phonon-induced gaps in graphene and graphite observed by angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136804 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem C. S. et al.. Effect of linear density of states on the quasiparticle dynamics and small electron-phonon coupling in graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 016802 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawlaty J. M., Shivaraman S., Chandrashekhar M., Rana F. & Spencer M. G. Measurement of ultrafast carrier dynamics in epitaxial graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 042116 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishioka K. et al.. Ultrafast electron-phonon decoupling in graphite. Phys. Rev. B 77, 121402 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. et al.. Ultrafast relaxation of excited Dirac fermions in epitaxial graphene using optical differential transmission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 157402 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luer L. et al.. Coherent phonon dynamics in semiconducting carbon nanotubes: A quantitative study of electron-phonon coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 127401 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. et al.. Time-resolved Raman spectroscopy of optical phonons in graphite: Phonon anharmonic coupling and anomalous stiffening. Phys. Rev. B 80, 121403 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Breusing M., Ropers C. & Elsaesser T. Ultrafast carrier dynamics in graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 086809 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al.. Ultrafast relaxation dynamics of hot optical phonons in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 081917 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kang K., Abdula D., Cahill D. G. & Shim M. Lifetimes of optical phonons in graphene and graphite by time-resolved incoherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. B 81, 165405 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Kane C. L. & Dekker C. High-field electrical transport in single-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2941–2944 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae D.-H., Krauss B., von Klitzing K. & Smet J. H. Hot phonons in an electrically biased graphene constriction. Nano Lett. 10, 466–471 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H., Hu B. Y. K. & Sarma S. D. Inelastic carrier lifetime in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 76 115434 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Calandra M. & Mauri F. Electron-phonon coupling and electron self-energy in electron-doped graphene: Calculation of angular-resolved photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. B 76, 205411 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Tse W.-K., Hwang E. H. & Sarma S. D. Ballistic hot electron transport in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93 023128 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Xu S. et al.. Energy dependence of electron lifetime in graphite observed with femtosecond photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 483–486 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos G., Gahl C., Fasel R., Wolf M. & Hertel T. Anisotropy of quasiparticle lifetimes and the role of disorder in graphite from ultrafast time-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 267402 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fann W. S., Storz R., Tom H. W. K. & Bokor J. Electron thermalization in gold. Phys. Rev. B 46, 13592–13595 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti L. et al.. Time evolution of the electronic structure of 1T-TaS2 through the insulator-metal transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067402 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt F. et al.. Transient electronic structure and melting of a charge density wave in TbTe3. Science 321, 1649–1652 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse W.-K. & Sarma S. D. Energy relaxation of hot Dirac fermions in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235406 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bistritzer R. & MacDonald A. H. Electronic cooling in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 206410 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butscher S., Milde F., Hirtschulz M., Malic E. & Knorr A. Hot electron relaxation and phonon dynamics in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 203103 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Pashkin A. et al.. Femtosecond response of quasiparticles and phonons in superconducting YBa2Cu3O7–δ studied by wideband terahertz spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 067001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S. et al.. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M. Z. & Kane C. L. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Pisana S. et al.. Breakdown of the adiabatic Born-Oppenheimer approximation in graphene. Nature Mater. 6, 198–201 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss T. et al.. A versatile system for ultrahigh resolution, low temperature, and polarization dependent Laser-angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 023106 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1_text

S2_Graphite_trPES