Abstract

Creating highly electrically conducting cables from macroscopic aggregates of carbon nanotubes, to replace metallic wires, is still a dream. Here we report the fabrication of iodine-doped, double-walled nanotube cables having electrical resistivity reaching ∼10−7 Ω.m. Due to the low density, their specific conductivity (conductivity/weight) is higher than copper and aluminum and is only just below that of the highest specific conductivity metal, sodium. The cables exhibit high current-carrying capacity of 104∼105 A/cm2 and can be joined together into arbitrary length and diameter, without degradation of their electrical properties. The application of such nanotube cables is demonstrated by partly replacing metal wires in a household light bulb circuit. The conductivity variation as a function of temperature for the cables is five times smaller than that for copper. The high conductivity nanotube cables could find a range of applications, from low dimensional interconnects to transmission lines.

Since its discovery1, researchers have tried to translate the excellent properties of individual carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to larger assembled components. Among these, a macroscopic cable that would replace metals as a universal conductive wire would have large applicability2, such as electricity transmission, aerospace and automobile industry. Several methods have been developed for creating multi-walled, double-walled and single-walled carbon nanotube based fibers based on wet and dry spinning methods, over the years2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The main premise for these works has been to generate nanotube fibers with good mechanical properties. The electrical properties have also been reported with resistivities over a large range between 7.1*10−3 to 2*10−6 Ω.m. In the supplementary information provided (Supplementary Table S1), we have listed and compared the resistivities of various nanotube fibers and metals prepared by a variety of techniques. For these fibers, up to now, their resistivity values are 2 to 3 orders higher than that for oxygen free Cu, (1.68*10−8 Ω.m), one of the most conducting metals widely used in current carrying applications.

Results

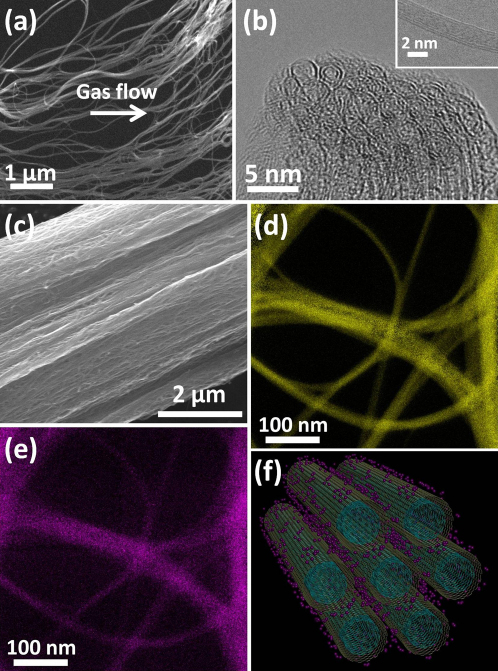

Here we report the fabrication and doping of carbon nanotube cables (we have chosen to use the terminology “cable” rather than fiber, as the main application pursued here is electrical transport), with resistivity one order of magnitude closer to the resistivity of Cu than the predecessors. We believe that the superior conductivity is achieved by a synergistic effect of the unique structure of the CNTs, the rational design of processing and doping. Figure 1 (a) shows the nanotubes aligned in one direction, (see Methods and Supplementary Video S6 for processing information). Supplementary Figure S2 shows the nanotube bundles interconnected and formed into a continuous network (Macroscopically the continuous network has an open-ended cylindrical shape, which we call nanotube “stocking”). The small bundles and the nanotubes by themselves are several microns long. After the nanotubes were fabricated into the cable as shown in supplementary Fig. S2, the natural alignment of the nanotube “stocking” was retained which turns out to be beneficial for the conductivity of the cable. The nanotubes we have used here (Inset of Fig. 1b) are double-walled (DWNT); the diameters are in the range of 2–3 nm and uniform (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Morphology of the raw DWNTs and iodine doped DWNT cable, as well as composition of iodine doped DWNTs.

(a) SEM image of a small piece of the carbon nanotube film peeled off from the “stocking”. Carbon nanotubes are aligned in the gas flow direction as marked by the white arrow. (b) TEM image of a DWNT bundle tip. (c) SEM image of the iodine doped cable. Nanotubes are aligned in the long axis direction of the cable. (d) Elemental mapping of carbon by Gatan image filter (GIF). (e) Elemental mapping of iodine. (f) A schematic illustrating the speculated model for iodine doped nanotube bundle. The iodine atoms are decorating the surface of the nanotubes.

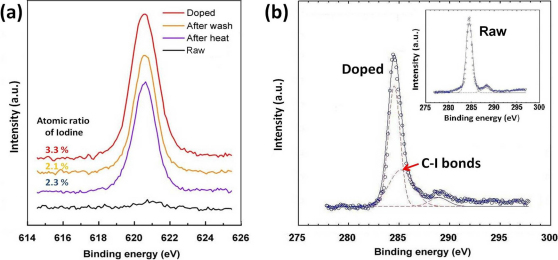

To improve the conductivity of the raw DWNT cable, the nanotubes were doped with iodine20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The raw DWNT cables were placed in the iodine vapor at 200°C for 12 hrs. Figure 1 (c) shows that the surface morphology of the iodine doped cable are similar to the raw cable. By SEM, we could not observe changes in diameter or any other morphology changes as a result of the iodine doping. Supplementary Figure S3 shows high contrast dark spots distributed over the surface of DWNTs, which could correspond to iodine clusters and atoms. The GIF elemental mappings for carbon and iodine as shown in Fig. 1 (d) and Fig. 1 (e) indicate that the location of carbon and iodine overlap, suggesting that iodine is uniformly present within the cable. Figure 1 (f) is a schematic for the proposed model, where the iodine atoms are homogeneously adsorbed on the surface of DWNTs. The molecular simulation shows that iodine atoms are less likely to penetrate into the inter-layer spacing or inside of the tubes, especially when they are well capped. For the DWNT bundles, the iodine atoms can penetrate into interstitial spaces between tubes and form an intercalated structure. To reveal the bonding of iodine atoms with the DWNTs we observed their x-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS). The doped cable without any further treatment has an iodine atomic percentage of 3.3%. After washing and sonicating in ethanol, the iodine concentration drops to 2.1%. In an independent experiment, the doped cable was heated in vacuum (150°C for 72hrs),which brought the iodine level to 2.3% (Fig. 2 (a)). These experiments show that the physically bonded iodine can be removed and the iodine remained on the surface of the DWNTs has a relatively strong chemical bonding. In comparison to the carbon XPS spectra before and after the doping (inset of Fig. 2(b) and Fig. 2(b), respectively), we can see the peak appearing at 285.2 eV after the doping, which corresponds to the energy of the C–I bonds. The peaks at 284.5 eV and 288.7 eV are assigned to C–C and C–O bonds, respectively. The C–O bonds are introduced during the purification procedure.

Figure 2. XPS spectra of the I-doped cable.

(a) Iodine spectra at different treatments. The black and red lines are the spectra for the cable before and after the iodine doping, respectively. The yellow line is collected from the doped cable after it was washed by ethanol. The blue line is collected from the doped cable after it was heated in the vacuum oven at 150°C for 72hrs. Inset of (b) and (b) are the XPS spectra for the cable before and after the iodine doping. The spectra curves (blue circles) are de-convoluted (dashed lines) by Gaussian fitting (solid lines), indicating multiple bonding energies.

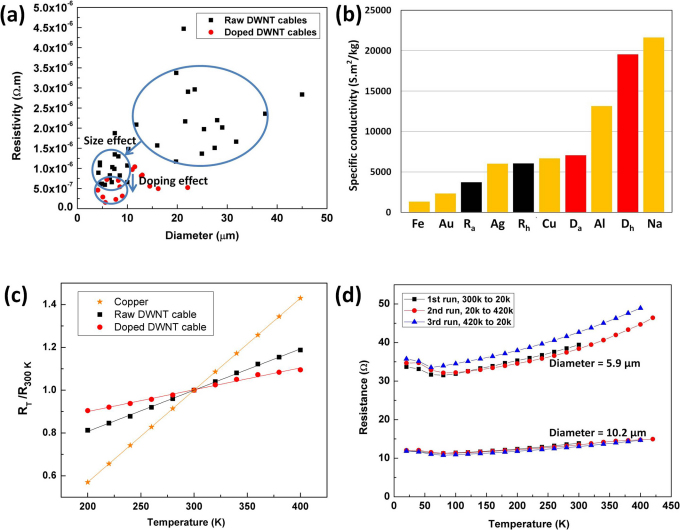

Resistivity of 34 raw DWNT cables with a diameter varying from 4.1 μm up to 44.7 μm was measured. Figure 3 (a) shows that statistically the cables of diameter >10 μm have larger resistivity compared to cables of diameter <10 μm. The size effect could be due to the fact that defects such as voids are invariably introduced into the larger cables during the fabrication process. The lowest resistivity found for the raw cables is ∼5*10−7 Ω.m. After doping with iodine, the cables further decreased in resistivity. The chemically bonded iodine as acceptors form (I3)− and (I5)− polyiodide chains in the intercalated sites, while mobile holes are created in the DWNTs. Due to the increasing density of mobile holes, the electrical conductivity of the cables was improved by the iodine doping21,22. X-ray diffraction spectra (Supplementary Fig. S4) shows that the (002) peak at 2θ∼10.86° corresponding to the inter-layer spacing between the outer and inner wall of the DWNTs shifts to the higher angle after the iodine doping. The shift is due to the suppression of the inter-layer spacing from 3.76 Å to 3.63 Å. The X-ray spectra could be a direct indication of charge transfer and covalent bond formation. The lowest resistivity observed in our cables corresponds to ∼1.5*10−7 Ω.m for the doped cables. Although the raw DWNT cables are not as conductive as metals, their specific conductivity (conductivity/weight) value is very high as the density of the nanotube cable is much lower than the density of metals. The raw DWNT cables have an average density of 0.28 g/cm3 and the iodine doped cables have an average density of 0.33 g/cm3. In terms of specific conductivity, the raw and doped cables are comparable with metals. For the iodine doped cables, the highest specific conductivity of 1.96*104 S.m2/kg was observed, which is higher than that of Al and Cu, but slightly lower than that of sodium, which has the highest specific conductivity of among metals of 2.16*104 S.m2/kg. A comparison in specific conductivity among raw, doped DWNT cables and a variety of metals is shown in Fig. 3 (b).

Figure 3. Electrical properties of the DWNT cables.

(a) The resistivity as a function of diameter for 34 raw DWNT cables and 15 iodine doped cables. (b) A comparison in specific conductivity among raw, doped cables and several metals. Ra and Rh represent for the average and the highest one for the raw cables. Da and Dh are the values for the doped cables. (c) The relative resistance as a function of temperature. (d) The resistance as a function of temperature for two doped cables. The thermal treatment for the cable of 10.2 μm in diameter is continuous, but for the cable of 5.9 μm in diameter, after the 2nd run of the heating process, the temperature was held at 420 k for 4 hrs, and then continued with the 3rd run.

Copper is the most commonly used raw material for conducting wires. In this study, we compared the relative resistance (the ratio of the measured resistance, RT to the resistance at 300 K, R300 K) of our cables with that of copper in the temperature range from 200 K to 400 K (normal operating temperature range for conducting wires). As shown in Fig. 3 (c), the reduced resistance versus temperature curves for copper and the DWNT cables are both linear from 200 K to 400 K. For the iodine doped cable, the resistance at 200 K to 400 K varies by −9% and 9% with respect to the resistance at 300 K. By contrast, the corresponding variations in copper are −43% and 43%31. We also studied the stability of the electrical properties for the iodine doped cables. At room temperature, the doped cables kept the resistance value at a constant level for the whole testing period of a minimum seven days. Figure 3 (d) shows the resistance as a function of temperature measured on two of the doped cables. In the first experiment, a 10.2 μm cable was continuously cooled down from room temperature to 20 K, heated up to 420 K, and cooled down to 20 K again. The heating/cooling rate was 1 K/min. The resistance versus temperature plot shows no hysteresis. This indicates that the iodine doping is stable upon the thermal cycling in this time scale.

Current carrying capacity is a property which measures the maximum current that can be passed through the unit cross sectional area of a conducting medium before it fails. An individual MWNT has extremely high current carrying capacity of 109–1010 A/cm2 32,33. This compares with nanoscale copper having a capacity of 106 A/cm2 34. However, the current carrying capacity for the macroscopic nanotube cables as reported in literature is much lower than that for individual single-walled nanotubes, 105 A/cm2 33. That finding is consistent with our results based on seven raw and seven iodine doped DWNT cables, which have current carrying capacities ranging from 104 to 105 A/cm2. Although the macroscopic cables do not have the extremely high current carrying capacity of individual nanotubes, they still have a sufficiently high capacity to be capable of loading utilities even for small diameter cables. From W. H. Preece's formula, we calculated the current carrying capacity of the copper wires in open air to be104 to 105 A/cm2 (The copper wires of diameter varying from 5 μm to 100 μm)35. DWNT cables' current carrying capacity is competitive to that of copper wires.

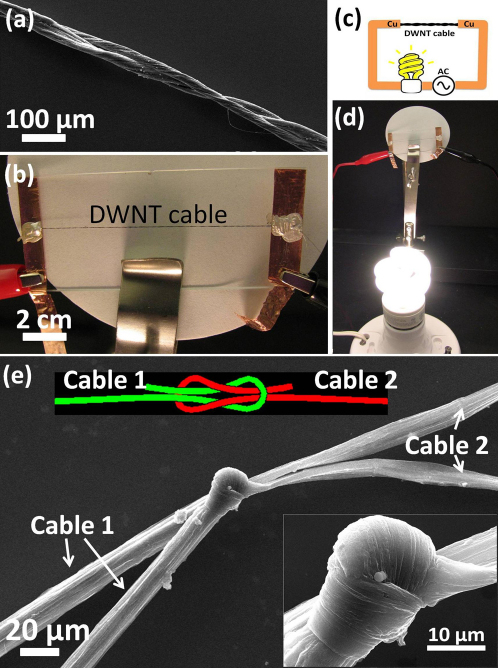

The nanotube cables also have the ability to be joined and assembled into larger structures. For example, two parallel DWNT cables were twisted and braided into one as shown in Fig. 4 (a). Before twisting, the two cables had resistances of 24 Ω and 20 Ω individually. Theoretically, the twisted thick cable from these two cables in a parallel configuration should have a resistance of 10.9 Ω (Rtheoretical = 24 Ω *20 Ω/ (24 Ω +20 Ω). From the measurement, we found that the assembled thick cable has a resistance of 10.5 Ω. This difference might be due to fact that the twisting renders better packing of the nanotubes in the cables and hence decreases the electrical resistivity of the individual cables themselves. This is a good indication suggesting that larger cable/wire structures of any arbitrary sizes can be built from the individual cables without sacrificing their electrical properties. Two individual cables (cable 1, diameter = 13 μm; cable 2, diameter = 11.5 μm) were also serially connected by a tie as shown in Fig. 4 (e). The two cables were knotted by a micromanipulator. Traditional weaving techniques used in the textile industry should also be applicable for making such connections between cables. The resistivity of cable 1 and 2 individually are 9.6*10−7 Ω.m and 9.35*10−7 Ω.m, respectively. Based on the resistivity, diameter and length of each cable (length is for the segment between the tie and its adjacent electrode), we can calculate the resistance of cable 1 and 2 as 15.33 Ω and 16.34 Ω. The assembled structure of cable 1, cable 2 and the tie has a resistance of 31.9 Ω. The resistance from the tie would then be ∼0.23 Ω suggesting that no significant resistance is introduced by the knot and indeed several short cables could be easily assembled to longer ones. The cable as the conducting wire is demonstrated in a circuit as shown in Fig. 4 (b) and (d). A household bulb (9 watts, 0.15A, 120V) was connected with the public power supply through the twisted wire. The light bulb was powered up. The circuit was turned on for 3 days. The nanotube cable functioned well for the whole testing period. In the circuit, the cable replaced a section of copper wire as shown in Fig. 4 (c). Here the nanotube cable is much smaller in diameter than copper wires. It is also found that the cables are mechanically quite robust. The average ultimate tensile strengths for the undoped and doped cables are 320 MPa and 640 MPa, respectively, comparable to metals. Supplementary Figure S5 shows the stress-strain curves for the two samples; after doping, the cable's strength increased but the strain to failure became smaller.

Figure 4. DWNT cables used in parallel and seires electrical circuits.

(a) SEM image of two cables twisted in a parallel configuration. (b) The image of the twisted cable. (c) Schematics of the circuit (d) The cable as a segment of conductive media connected with the household power supply and loaded with a light bulb (9 watts, 0.15 A, 120 V). (e) SEM images shows that cable 1 and 2 can be knotted and joined. Inset is a higher magnification SEM image of the tie.

Discussion

In summary, we have made double-walled carbon nanotube cables that outperform Cu and Al in specific electrical conductivity. Iodine doping effectively increases the conductivity of the cables, as well as their tensile strength. Using cables as the building blocks and employing different assembly methods, larger and longer wires and cables can be created and we have used this approach to demonstrate a nanotube wire circuit to power a household light bulb. These lightweight nanotube cables could be serious contenders for replacing metal wires in electrical transmission as they would have intrinsic advantages to metals such as high temperature stability and chemical resistance.

Methods

The cable preparation includes four steps: nanotube growth, nanotube purification, soaking in the sulfuric acid and shrinking.

Nanotube growth

Double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWNTs) were grown by flow chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method (See Supplementary Video S6)36,37.

Nanotube purification

The DWNTs as-grown contain catalysts. It was found that impurities cause degradation in conductivity. Therefore, we purified DWNTs before making them into cables. The DWNTs were first oxidized by heating the raw macroscopic DWNT bundle in air at 400°C for 1 hour. The oxidization treatment can attach oxidized functional groups to nanotubes and make DWNTs be of a better wettability with water. Then the oxidized DWNTs were soaked into a 30% hydrogen peroxide solution for 72 hours. This soaking process can crack the amorphous carbon and make the catalysts dissociate from the carbon nanotubes. Afterward, the DWNTs were transferred into a 37% hydrogen chloride solution and soaked for another 24 hours. Then, the DWNTs as received from the previous procedure were washed by DI water until they become neutralized38. After the purification, the catalyst weight percentage is below 1%.

Soaking in the sulfuric acid

The diameter of cables is determined by how much DWNTs would be used to make the cable. The purified DWNTs in water are in a bundled form because of van der Waals interaction between tubes. The big bundle would result in making a cable of diameter larger than 20 μm. To peel off a small amount of DWNTs from the bundle to make a cable of diameter sub-10 μm, the bundle needs to be spread. The DWNT bundle was loosen up and spread into thin films by soaking in 98% sulfuric acid for 24 hours. After the soaking treatment, the DWNTs have a form as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. From the thin film, a small amount of DWNTs in a ribbon form can be peeled off.

Shrinking

When the DWNT ribbon was taken out from the sulfuric acid solution, it would agglomerate into a spherical particle because the surface tension caused by the residual sulfuric acid is isotropic. To retain the length in the long axis direction of the ribbon, we applied the pulling force on the two ends of the ribbon to counteract the tension force from the sulfuric acid when the ribbon was taken out of the sulfuric acid solution. Then, the ribbon was dipped into the DI water to wash out the residual acid. Afterward, the ribbon was taken out of the water. Along with the water evaporation process, the ribbon shrunk into the cables. The shrinking was a synergistic effect of the van der Waals force between tubes and the surface tension force from the water. At the last step of shrinking, other solutions such as ethanol, acetone and chloroform can be the substitutions for water. Microscopically, the original loose DWNT networks shrunk into a dense form.

After the raw cables were prepared, the iodine doping was conducted by placing the raw DWNT cables in the iodine vapor (the iodine vapor concentration is 0.2 mol/l) at 200°C for 12 hrs.

Structure and composition analysis

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was applied to observe nanostructures of DWNTs and iodine doped DWNTs. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to measure the diameter of cables and to observe the structure and the morphology of DWNTs before and after each step of the processing. The elemental composition of the iodine doped cables was characterized by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). To understand the distribution of iodine atoms, the elemental mapping for the iodine doped DWNTs was obtained via a Gatan imaging filter (GIF) attached with the TEM. In addition, Polarized Raman spectra of the raw and iodine doped cables were collected for both the parallel and perpendicular directions to the long axis of the cables (See Supplementary Fig. S8). For this study, a 632 nm laser associated with an 1800/m grating were used. X-ray diffraction spectra were collected for both the raw and iodine doped DWNTs. The X-ray source was generated from a Mo target.

Electrical property measurements

Resistivity was calculated based on the length L, diameter D and resistance R of the cables using the formula, resistivity = R*D2*π/4/L. The calculation is based on the assumption that cables are in a cylindrical shape. In fact, the cross section of some cables is not an ideal circle but an ellipse. In the calculation, we used long axis length as the diameter. By this approximation, the real resistivity of the cable is lower than the calculated value. Diameter, D of each cable plugged into the formula was an average based on the measurements at three different locations along the cable's long axis direction. The data reported in this study was based on the cables with a diameter variation smaller than 10% along the cable's long axis direction. The resistance was characterized by a Keithley 2400 in a four-probe configuration. The representative I–V curve for reading the resistance of the cable was shown in Supplementary Fig. S9.

Current carrying capacity was defined by the ratio of the critical current to the cross sectional area. The cable was connected with a Keithley 2400, which was the current source by two electrodes. The current passing the cable was stepwise increased. The critical current was recorded at the moment that the cable was burned. The representative current versus time curve for recording the critical current was shown in Supplementary Fig. S10.

Mechanical property measurements

Tensile test was conducted on five undoped and five doped cables using an electrodynamic test system (Electroplus 3000, Instron). The strain rate was set at 0.2%/S.

Author Contributions

Y. Z and J.Q.W. contributed equally to this work. Y.Z. and J.Q.W. designed and carried out the experiments (CVD, SEM, TEM, XPS, Raman, fiber preparation, electrical test), and analyzed the data. P.M.A. and E.V.B. was responsible for the project planning. Y.Z., J.Q.W., R.V., P.M.A. and E.V.B. co-wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video-S5 (Ajayan)

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for this research from the Research Partnership to Secure Energy of America (RPSEA), the United States Department of Energy (grant No. D-74876) and AFRL (grant No. FA 8650-08-2-5061). We are also grateful to Zheng Liu, Padraig Monoley, James Huang (Boeing Research & Technology, Huntington Beach, CA), Andres Rodela and Fangbo Xu for helpful discussion.

References

- Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354, 56-58 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Ericson L. M. et al.. Macroscopic, neat, single-walled carbon nanotube fibers. Science 305, 1447-1450 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigolo B. et al.. Macroscopic fiber and ribbons of oriented carbon nanotubes. Science 290, 1331-1334 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton A. B. Super-tough carbon-nanotube fibres. Nature 423, 703 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Atkinson K. R. & Baughman R. H. Multifunctional carbon nanotube yarns by downsizing an ancient technology. Science 306, 1358-1361 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M., Li Y., Kinloch I. A. & Windle A. H. Mechanical properties of continuously spun fibers of carbon nanotubes. Nano Letters 5 (8), 1529-1533 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai R., West J. D., Luscher A. & Subramaniam V. V. Electrophoretic drawing of continuous fibers of single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 114307 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Koziol K. et al.. High-performance carbon nanotube fiber. Science 318, 1892-1895 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F. et al.. Ultrastrong, stiff and lightweight carbon-nanotube fibers. Adv. Mater. 19, 4198-4201 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chae H. & Kumar S. Making strong fibers. Science 319, 908-909 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis V. A. et al.. True solutions of single-walled carbon nanotubes for assembly into macroscopic materials. Nature nanotechnology 4, 830-834 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M. et al.. A multiscale study of high performance double-walled nanotube-polymer fibers. ACS Nano 4 (11), 6463-6476 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badaire S. Correlation of properties with preferred orientation in coagulated and stretch-aligned single-wall carbon nanotubes. J.Appl.Phys. 96 (12), 7509-7513 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz J., Glerup M., Paillet M., Bernier P. & Holzinger M. Production of pure nanotube fibers using a modified wet-spinning method. Carbon 43, 2397-2399 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov M. E. et al.. Spinning solid and hollow polymer free carbon nanotube fibers. Adv. Mater. 17 (5), 614-617 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jang E. Y. et al.. Macroscopic single-walled-carbon-nanotube fiber self-assembled by dip-coating method. Adv. Mater. 21, 4357-4361 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F. et al.. Strong carbon-nanotube fibers spun from long carbon-nanotube arrays. Small 3 (2), 244-248 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. et al.. Scratch-resistant, highly conductive, and high-strength carbon nanotube based composite yarns. ACS nano 4 (10), 5827-5834 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X. H. et al.. Continuous multilayered carbon nanotube yarns. Adv. Mater. 22, 692-696 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. S., Kim H. J., Fischer J. E., Thess A. & Smalley R. E. Conductivity enhancement in K- and Br- doped nanotube bundles. Nature 388, 255-257 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian L. et al.. Reversible intercalation of charged iodine chains into carbon nanotube ropes. Phys. Rev. Letts. 80 (25), 5560-5563 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J. E. Chemical doping of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 1079-1086 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi S. et al.. Chemistry of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 1105-1113 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari L., Prasad V. & Subramanyam S. V. Effect of iodine incorporation on the electrical properties of amorphous conducting carbon films. Carbon 41, 1841-1846 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Cambedouzou J. et al.. Raman spectroscopy of iodine-doped double-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 69, 235422 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kissell K. R., Hartman K. B., Van der Heide P. A. W. & Wilson L.. J. Preparation of I2@SWNTs: synthesis and spectroscopic characterizaition of I2-loaded SWNTs J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 17425-17429 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel T. et al.. Structual selective charge transfer in iodine-doped carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 67, 1190-1192 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Khoerunnisa F. et al.. Electronically modified single wall carbon nanotubes with iodine adsorption. Chem. Phys. Letts. 501, 485-490 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W. Y. et al.. Raman scattering and thermogravimetric analysis of iodine-doped multiwall carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80 (14), 2553-2555 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. I., Ihm J. & Kim G. Modification of the electronic structure in a carbon nanotube with the charge dopant encapsulation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 193110 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Copper wire tables. National Bureau of Standards Handbook 100 (U.S. government printing office, Washington D.C., Issued Feb. 21 1966). [Google Scholar]

- Wei B. Q., Vajtai R. & Ajayan P. M. Reliability and current carrying capacity of carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79 (8), 1172-1174 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Tang J., Zhang H., Shinya N. & Qin L. C. Ultrathin carbon nanotube fibrils of high electrochemical capacitance. ACS nano 3 (11), 3679-3683 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali R., Yang Y. X., Brenner K., Beck T. & Meindl J. D. Breakdown current density of graphene nanoribbons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 243114 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Preece W. H. Royal Soc. Proc. 36, 464 (1884). [Google Scholar]

- Wei J. Q. et al.. Preparation of highly pure double-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Chem. 13 (6), 1340-1344 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Ci L. J. et al.. Double wall carbon nanotubes promoted by sulfur in a floating iron catalyst CVD system. Chem. Phys. Letts. 359, 63-67 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. H., Shan H. W., Hauge R. H., Pasquali M. & Smalley R. E. A highly selective, one-pot purification method for single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 1249-1252 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video-S5 (Ajayan)

Supplementary information