Abstract

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common form of congenital intellectual disability. Although DS involves multiple disturbances in various tissues, there is little doubt that in terms of quality of life cognitive impairment is the most serious facet and there is no effective treatment for this aspect of the syndrome. The Ts65Dn mouse model of DS recapitulates multiple aspects of DS including cognitive impairment. Here the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS was evaluated in an associative learning paradigm based on olfactory cues. In contrast to disomic controls, trisomic mice exhibited significant deficits in olfactory learning. Treatment of trisomic mice with the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine resulted in a significant improvement in olfactory learning. Collectively, our study indicates that olfactory learning can be a sensitive tool for evaluating deficits in associative learning in mouse models of DS and that galantamine has therapeutic potential for improving cognitive abilities.

Down syndrome (DS) was first described by the English physician John Langdon Down in 1866. It was subsequently shown that this condition is caused by trisomy of chromosome (Chr) 21, which in the majority of cases, is present in its entirety and is of maternal origin (reviewed in1,2). Although DS involves multiple disturbances in a relatively wide range of tissues there is little doubt that in terms of quality of life of the person and parents, relatives and caretakers, cognitive impairment is the most serious aspect of this syndrome. Mental retardation is evident as lower verbal and mental performance in the mild to moderate range and individuals with DS show distinct delay in language development, deficits in auditory sequential processing and verbal short-term memory3. In addition to these impairments, as children with DS grow into adults, they frequently incur an age-associated neuronal loss, reminiscent of Alzheimer's disease4,5,6,7. By the fourth decade, most DS adults show signs of early onset Alzheimer's, with the first presentation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in regions associated with learning and memory4,8,9,10.

The Ts65Dn mouse is a segmental trisomy mouse model of DS containing a third copy of the distal region of mouse Chr 16 that contains 94 genes orthologous to the DS critical region of human Chr 2111. Ts65Dn mice survive to adulthood and recapitulate multiple biochemical, morphological and transcriptional aspects of DS as it occurs in humans11,12,13 and has become an informative animal model of this syndrome (reviewed in14). Although Ts65Dn mice perform similarly to disomic controls in visual placing, balance, prehensile reflex, traction on a horizontal bar, motor coordination15, and olfaction orienting16, neural cognitive deficits17,18,19, motor and behavioral abnormalities have been noted in these mice4,20,21,22. Deficits in spatial learning and memory have been especially prominent with significant impairment in both Morris water maze and radial maze performance compared to disomic littermate controls13,15,23,24,25. Other behavioral abnormalities include locomotor hyperactivity and stereotypic behavior24,26. We wanted to avoid the potential confound between motor deficits and performance in spatial learning tasks, and also estimate learning using ethologically relevant cues.

Mice are macrosmatic animals, and use their acute sense of smell in many aspects of their lives that relate to learning and memory, from communicating with conspecifics, finding food to avoiding predators27,28. In spite of the importance of this sensory modality, few studies have dealt with olfactory-based tasks in Ts65Dn mice16. In this study, we report the first investigation of associative olfactory learning performance in trisomic Ts65Dn mice and disomic littermates in a computerized go-no-go odor discrimination task. We used a complementary hidden peanut butter finding test to assess whether changes in sensory-motor abilities could affect odor responses. Additionally, because Ts65Dn mice show degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons4,19,29 that correlates with their cognitive decline19, and the fact that deficits in cholinergic modulation in Ts65Dn mice19,29,30,31 are likely to affect olfactory learning32, we hypothesized that the administration of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor drug galantamine hydrobromide would ameliorate their olfactory learning behavior. We observed that trisomic mice exhibited significant deficits in olfactory based learning compared to disomic littermate controls and that this deficit could be rescued by galantamine treatment. Collectively, our study indicates that olfactory learning performance can be a sensitive tool for evaluating deficits in associative learning in mouse models of DS and that galantamine has therapeutic potential for improving cognition in this syndrome.

Results

Trisomic Ts65Dn mice perform worse than controls in olfactory learning

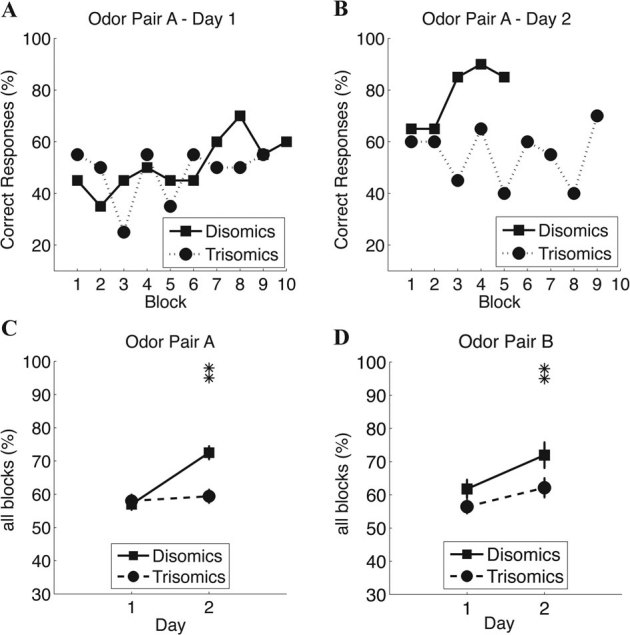

Ten disomic and ten trisomic mice were tested on the olfactory learning tasks. Figures 1 A and B show representative behavior of individual disomic and trisomic mice during the first and second test-days in the odor detection task (Task A, citral vs. mineral oil).

Figure 1. A and B. Examples of olfactory learning behavior of trisomic and disomic mice exposed to odor pairs A and B.

Bold lines represent disomic mice, and dashed lines the trisomic mice. (A) Representative responses of a single trisomic (dashed line with circle markers) and disomic mice (continuous line with square markers) on the first test-day on odor pair A. (B) Same as A, but for the second test-day. (C) Mean correct responses for all blocks within each section on the first and second days for odor pair A. (D) Same as C, but for odor pair B. Note that these mice do not achieve learning in day 1. This indicates that mice of the C3H background take two days in achieving learning in this task. Mean (circle or square markers) and standard error bars are shown for each case. Significant differences are marked with one (P<0.05) or two asterisks (P<0.01). The y-axis shows the percent of correct responses.

Figures 1 C and D show the average percent correct for the two training days on each odor pair. A repeated measures ANOVA (genotype*odor-pair*sex) indicates a significant effect of the genotype (F = 9.6; p = 0.007), as well as an overall significant improvement from day 1 to day 2 (F = 7.1; p = 0.018). There was a significant odor pair*sex interaction (F = 6.8; p = 0.02). Post-hoc analyses reveal that performance of disomic mice improved significantly from day 1 to day 2 (58.1% to 73.5%, p = 0.004, Tukey's HSD). This was not the case for trisomics (57.5% to 61.7%, p = 0.75). Performance on Day 2 alone was significantly better for disomics than trisomics (p = 0.034).

Collectively these results indicate that trisomics exhibit impaired learning when compared to their disomic counterparts. To ensure that the difference in learning did not stem from initial behavioral differences when beginning the task, we performed a detailed behavioral analysis on the first 5 blocks of the first day of learning (citral vs. Mineral Oil). There was no significant difference in the number of licks between disomic and trisomic mice (on rewarded, unrewarded trials or both: Supplemental Figure 1, Mann-Whitney U test: U = 9, p = 0.46). This indicates that subsequent differences in learning were not due to differences in the initial sampling strategy, or to differential emotional responses to the testing apparatus.

Galantamine treatment elicits better performance in olfactory learning in trisomic mice

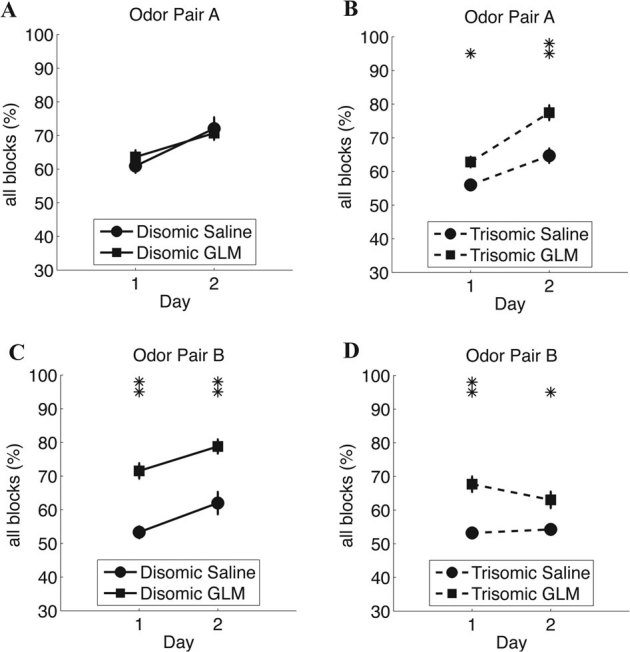

We tested the effect of a chronic treatment with galantamine or saline (shams) on the learning performance of disomic and trisomic male mice (Fig. 2). The performance of Ts65Dn mice was significantly improved by chronic injections of galantamine. Repeated measures ANOVA (treatment*odor-pair*day) reveals a significant effect of the treatment (F = 5.1; p = 0.038), day (F = 5.1; p = 0.02), and interaction day*odor-pair (F = 6.6; p = 0.02). The improvement from D1 to D2 was only evident for the citral vs. mineral oil task (HSD Tukey post-Hoc: p = 0.007). While galantamine improved the overall performance (Tukey post-Hoc test p = 0.038), the effect could not be narrowed down to one odor pair. In spite of an apparent increase in performance, galantamine had no significant effect on disomic mice (repeated measures ANOVA (treatment*odor-pair*day; treatment effect: p = 0.121). Performance increased from D1 to D2 (post-Hoc Tukey: p = 0.002), for both treatment groups (saline p = 0.035, galantamine p = 0.009).

Figure 2. Olfactory learning behavior of odor pairs A and B by disomic and trisomic mice on chronic treatment with galantamine or saline.

Olfactory learning behavior of disomic (continuous lines) and trisomic (dashed lines) mice under chronic treatment with galantamine (square markers) or saline (circle markers), and exposed to odor pairs A and B. (A) Mean number of correct responses of disomic mice on galantamine and saline for all blocks on odor pair A. (B) Same as A, but for trisomic mice. (C) Same as A, but for odor pair B. (D) Same as B, but for odor pair B. Mean (circle or square markers) and standard error bars are shown for each case. Significant differences are marked with one (P<0.05) or two asterisks (P<0.01). The y-axis shows the percent of correct responses.

Disomic and trisomic mice do not differ at performance in a peanut butter finding test

Additionally, we performed a hidden peanut butter finding experiment. Under saline treatment, both disomic and trisomic mice needed approximately the same time to find the peanut butter (mean±SEM = 88.37±21.71 s, n = 8 and 99.68±19.48 s, n = 10, P = 0.17, T-Test). Similar latencies were achieved under galantamine treatment (mean±SEM; disomics: 88.00±22.88s, n = 7 and trisomics: 103.55±20.27 s, n = 9, P = 0.37, T-Test). The treatment had no effect on either disomics or trisomics (T-test: p = 0.41 and p = 0.47, respectively).

Discussion

The observed olfactory learning performances of trisomic and disomic mice in the olfactometer (Fig. 1) constitutes the first demonstration that olfactory-based associative learning is negatively affected in Ts65Dn mice. The poor performance in the associative learning task, combined with documented deficits in spatial cognition, strongly support a widespread effect of this trisomy on adaptive behaviors. This wide array of cognitive and sensory deficits validate the Ts65Dn mouse as a valid model of Down Syndrome. The deficit in olfactory-based associative learning is likely due to both deficits in learning and odor perception. These deficits are well-documented in human: mild to moderate mental retardation is evident in verbal and mental performance3 and olfactory deficits33,34,35,36,37,38.

The presence of a third copy and presumed overexpression of genes from Chr 21 in humans with DS, and Chr 16 in Ts65Dn mouse39, result in a complex perturbation of multiple processes involved in neurological development and function10. Many genes expressing olfactory membrane receptors40 are located on Chr 21 in humans41 and Chr 16-17 in mice39, but the neurological effects of the presumed overexpression of these olfactory genes is not known. On one hand, olfactory receptor proteins are expressed from a single allele, and an overrepresentation of the olfactory receptor genes is unlikely to lead to an overexpression of olfactory receptor proteins42,43. However it is unknown if this overrepresentation of the olfactory receptor genes could generate a down-regulation effect on the expression of certain olfactory receptor proteins that could decrease the sensitivity of the olfactory system to certain odorants. Conversely, changes in expression of other genes such as ApoE epsilon 4 could mediate an olfactory associative learning deficit36. Previous work has provided evidence of olfactory impairment in patients with DS34,35,36,38 and a role for cholinergic neurodegeneration in this aspect of DS pathology is supported by the observation that olfactory loss is also a common facet of Alzheimer's disease44,45. It is difficult to dissociate the olfactory effects that could be caused by the overrepresentation of olfactory receptor genes from those caused by the neural degeneration associated with the early onset of Alzheimer's disease34,35. This is a limitation of our approach, since the olfactometer cannot separate learning and olfactory impairment. Thus, we do not know how changes in protein expression induced by DS affect olfactory learning and further studies will be required to investigate these questions.

Another neurological consequence associated to the overexpression of genes in Ts65Dn mice is the diminished number of cholinergic neurons on the basal forebrain19,46, which likely is one of the main causes of their learning deficits, and could underlie olfactory deficits. The cholinergic neurons on the basal forebrain innervate the cerebral cortex in a relatively widespread manner47,48,49, and the acetylcholine release from these basal forebrain cholinergic neurons modulates the cortical neurons and consequently the cerebral cortex50. It is known that the manifestations of dementia in DS have been associated with a frontal lobe dysfunction10, which could be associated with the reduced number of cholinergic neurons19. In addition, decreased number of cholinergic neurons in the horizontal diagonal band of Broca in the basal forebrain would result in decreased projection of axons to the olfactory bulb thereby affecting olfactory processing32,51,52,53.

If the deficit in neural activity is due to decreased Ach neuron expression, it should be compensated by using pharmacological activators of cholinergic neurons54,55, like galantamine that boosts Ach responses in the neural terminals and nicotinic Ach Receptors56,57. In this way, the galantamine activation of cholinergic neuron in the basal forebrain that project to cortical neurons and olfactory areas could conceivably activate the cholinergic neurons and possibly rescue some of the neurological and behavioral deficits associated with DS. This possibility is consistent with previous work that has shown that perinatal dietary supplementation with choline acts to significantly improve cognition and emotion regulation in the Ts65Dn mouse model58.

In the present study we observed that the galantamine treatment enabled trisomic mice to reach a performance level comparable with that of disomic mice (Fig. 2). A significant improvement in the percent of correct choices occurred in disomic and trisomic mice under chronic treatment with galantamine. Galantamine treatment improved the performance of trisomic mice in both tasks, while it only improved the performance of disomic mice on the most difficult of them (task B). An explanation for the lack of effect of galantamine on the performance of disomic mice on odor pair A comes from the fact that they already achieved high scores on this task leaving little scope for improvement. Thus, galantamine an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and an agonist of nicotinic receptors elicits improved performance in an olfactory learning task in trisomic Ts65Dn mice. Interestingly, in the past no improvement in behavioral performance in the Morris Water Maze was found in these mice after treatment with the acetylcholine esterase inhibitor donepezil59. In the future it makes sense to test galantamine and donepezil in parallel experiments in olfactory learning and MWM. Finally, in spite of the fact that we cannot dissociate totally olfactory deficits from learning deficits at a behavioral level, the positive action of galantamine in our mice taken together with evidence from literature showing that non-olfactory learning deficits in Ts65Dn are linked to a diminished number of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain, reinforce the hypothesis that the lower scores on the olfactory discrimination task is more likely an impairment in the acquisition of the learning rule in consequence of the impaired basal forebrain-neocortex circuitry than due to a malfunctioning of the olfactory system. Future studies will have to determine whether these are olfactory or sensory deficits.

Galantamine has been used clinically to stabilize cognition in patients with Alzheimer's disease60. Since DS has been strongly linked with the early development of Alzheimer's disease10, and autopsy of patients with Alzheimer's disease revels lesions in the cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain61, the results from the present work indicate that galantamine has significant therapeutic potential for alleviating learning deficits in humans with DS.

However, additional studies of galantamine treatment in Ts65Dn mice and controls are needed to dissociate their transient and permanent effects prior to translation to a clinical trial.

Methods

Animals

The Ts65Dn subjects were either obtained directly from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME)(B6EiC3Sn a/A-Ts(17<16>65Dn)) or by mating female carriers of the partial trisomy to hybrid males (C57Bl/6 Jeicher x C3H/HeSnJ F1) obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. They were genotyped by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using a probe for the centromere of mouse Chr 16 and Chr 1762.

In this study we used a total of 28 trisomic Ts65Dn mice and 26 disomic littermates. 45 male and 9 female mice between 3 and 6 months were used. 10 trisomic and 10 disomic naïve mice were used for the characterization of the olfactory learning behavior in the go-no go task. Specifically for testing the effect of galantamine on mouse olfactory behavior, a group of 8 disomics was treated with daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of galantamine and another group of 8 disomics was treated with daily i.p. injections of saline vehicle. In the same way, a group of 9 trisomic Ts65Dn mice was treated with saline vehicle and another 9 with galantamine. The same 34 mice used for testing the effect of saline and galantamine on the go-no-go test were also used after on the hidden peanut butter finding test. All experiments were approved by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center institutional animal care and use committee and were performed according to the NIH standards for animal care and use.

Operant conditioning behavior

We used the behavioral go-no go olfactory learning methods63 detailed briefly as follows. In order to elicit motivation to obtain water reward, animals were water-deprived to 80-85% of original body weight. Then mice were trained during 3 days to poke in an odor sampling port and then respond by licking the water delivery port in the presence of 10% citral in mineral oil to receive a drop of water. Each trial is initiated by the mouse inserting its head in the odor-sampling port and is followed by a 2.5 sec delivery of the odor. Reinforcement is delivered if the mouse licks on the water-delivery tube at least once in each of the last four 0.5 sec intervals of the 2.5 sec odor delivery period.

Next, the mice learned to respond to the S+ (rewarded) odor and not to the S- (unrewarded) odor. S+ and S- trials are presented in a pseudo-random order with the following restrictions: i) equal number of rewarded and unrewarded trials in each block of 20 trials and ii) no more than 3 of the same trials in a row. Each session has a maximum of 10 blocks (200 trials). The session was terminated either when the animal completed 10 blocks or when the animal became satiated and stopped initiating trials for over eight minutes. To determine the percentage of correct responses in each block of 20 trials the following formula was used:

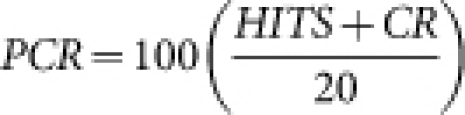

|

where PCR are the percent of correct responses, HITS are rewarded trials in which the subject successfully obtained the reward, and CR are correct rejections - where the animal restrained from licking on an unrewarded trial.

Olfactory stimuli for the go-no go task

Each subject was tested in two different learning tasks:

Task A (odor detection): Citral 10% (S+, rewarded), Mineral oil (S-, unrewarded)

Task B (odor discrimination): 2-Heptanone 1% (S+); 3-Heptanone 1% (S-)

Task A is a simple discrimination task that used mineral oil alone, a diluent with relatively weak odor as the unrewarded stimulus64. A large difference in odor quality was used in task A (strong citral vs. weak odor mineral oil) because a strong difference in odor quality is necessary to when mice first learn to perform in the odor discrimination task63. Task B is a theoretically more challenging problem presenting a new odor pair composed of 2-Heptanone 1% as the S+ and 3-Heptanone 1% as the S- (Odor Pair B). 7 disomic and 6 trisomic subjects unable to reach >70% correct in the last two blocks of the last day of the 2 day training period by licking the water delivery port in the presence of 10 % citral were removed from the study. For the others, task A was performed followed by task B. In the olfactometer odors are generated by mixing a 50 cc/min stream of air from the headspace of the odor-saturator bottle with a 1950 cc/min stream of clean air, the odor experienced by the mouse is 2.5% of the headspace concentration above the liquid odorant. Odors in the saturator bottle were diluted in mineral oil.

Testing the effect of treatment with galantamine on go-no go olfactory learning behavior

We tested the effects of galantamine treatment on olfactory learning behavior in a separate group of naïve mice. During days when the mice were undergoing olfactory learning in the go-no go task animals were injected intraperitoneally daily with 3 μg/g (drug/body weight) of galantamine hydrobromide (Tocris Cookson Inc, Catalog number 0686) diluted in sterile saline, and tested 4 hours after the injection56,57. Daily chronic injections of galantamine hydrobromide started during the 3-day training period in the presence of S+ only, and continued throughout the go-no-go test in the presence of S+ and S-. Trisomics as well as disomic mice were split into two groups, one receiving the galantamine, the other receiving sham injections of sterile saline alone. Because performance in the olfactometer tends to improve with time, it is not possible to compare the performance of the same individual on different treatments. The effect of galantamine was therefore assessed in independent groups. The total length of treatment with galantamine was 10 days.

Hidden peanut butter finding test

A simple digging test was used as an independent test of mouse olfactory ability in a task to find an odor reward hidden in the cage65. Mice of all 4 groups (both genotypes, both treatments) were given peanut butter, an appetitive stimulus they were allowed to eat, on the day before to the test day. Then, on the next day, mice were placed in the middle of a clean cage with a Petri dish with peanut butter reward hidden under the 5 cm thick bedding, and we recorded the latency to dig and find the peanut butter reward.

Statistics

The percent of correct responses per block were obtained for each animal, and then the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were calculated for each group. Statistical analyses for significance of differences in odor learning were performed using the Statistica software (StatSoft, Inc.) and the Matlab Statistics Toolbox (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). The mean percent correct for all blocks per session (MPC) for each odor pair was analyzed and is shown in the figures. Groups were compared using unpaired t tests and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), using performance on day 1 and day 2 for each odor pair as the repeated measures. Tukey's Post-Hoc tests were then used, where p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

FS helped generate an experimental design, assembled and troubleshooted the olfactometers, performed a subset of the experiments, plotted the main figures, helped analyzing the data and writing the manuscript. NB performed statistical analysis of the data and helped write the manuscript. MB performed a subset of the experiments. KM helped with the experimental design, genotyping and writing the manuscript and DR helped develop an experimental design, troubleshoot the olfactometer, analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information Galantamine improves olfactory learning in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for funding of this project by the Anna and John Sie Foundation to DR and KNM. DR gratefully acknowledges support from NIH grants DC008855 and DC04657. KNM gratefully acknowledges financial support from NICHD grant HD045224. FS thanks Michael Hall for build the olfactometers hardware.

References

- Roizen N. J. & Patterson D. Down's syndrome. Lancet 361, 1281–1289 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis S. E., Lyle R., Dermitzakis E. T., Reymond A. & Deutsch S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: from genomics to pathophysiology. Nat Rev Genet 5, 725–738 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hick R. F., Botting N. & Conti-Ramsden G. Short-term memory and vocabulary development in children with Down syndrome and children with specific language impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol 47, 532–538 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C. L., Bimonte H. A. & Granholm A. C. Behavioral comparison of 4 and 6 month-old Ts65Dn mice: age-related impairments in working and reference memory. Behavioural brain research 138, 121–131 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Piccione R. et al.. On dendrites in Down syndrome and DS murine models: a spiny way to learn. Progress in neurobiology 74, 111–126 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. et al.. Similar deficits of central histaminergic system in patients with Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Neurosci Lett 222, 183–186 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegiel J. et al.. Neuronal loss and beta-amyloid removal in the amygdala of people with Down syndrome. Neurobiology of aging 20, 259–269 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessarollo L. Brain disorders: getting 'Down' to the gene. Nature neuroscience 13, 909–910 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B. Cognitive deficits in Down syndrome: narrowing 'Down' to Olig1 and Olig2. Clin Genet 79, 47–48 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner K. et al.. Down syndrome: from understanding the neurobiology to therapy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 14943–14945 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davisson M. T., Schmidt C. & Akeson E. C. Segmental trisomy of murine chromosome 16: a new model system for studying Down syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res 360, 263–280 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti L. et al.. Olig1 and Olig2 triplication causes developmental brain defects in Down syndrome. Nature neuroscience 13, 927–934 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R. H. et al.. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behaviour deficits. Nature genetics 11, 177–184 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seregaza Z., Roubertoux P. L., Jamon M. & Soumireu-Mourat B. Mouse models of cognitive disorders in trisomy 21: a review. Behavior genetics 36, 387–404 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escorihuela R. M. et al.. Impaired short- and long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett 247, 171–174 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S. L. et al.. Characterization of sensorimotor performance, reproductive and aggressive behaviors in segmental trisomic 16 (Ts65Dn) mice. Physiology & behavior 60, 1159–1164 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L. A. & Crnic L. S. Age-related deficits in context discrimination learning in Ts65Dn mice that model Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Behavioral neuroscience 115, 1239–1246 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L. A., Frisone D. F. & Crnic L. S. Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome, have deficits in context discrimination learning suggesting impaired hippocampal function. Behavioural brain research 118, 53–60 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm A. C., Sanders L. A. & Crnic L. S. Loss of cholinergic phenotype in basal forebrain coincides with cognitive decline in a mouse model of Down's syndrome. Experimental neurology 161, 647–663 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A. C., Walsh K. & Davisson M. T. Motor dysfunction in a mouse model for Down syndrome. Physiology & behavior 68, 211–220 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdzicki Z. & Siarey R. J. Understanding mental retardation in Down's syndrome using trisomy 16 mouse models. Genes, brain, and behavior 2, 167–178 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger G. R., Schmidt C. & Davisson M. T. Operant conditioning in the Ts65Dn mouse: learning. Behavior genetics 34, 105–119 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussons-Read M. E. & Crnic L. S. Behavioral assessment of the Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome: altered behavior in the elevated plus maze and open field. Behavior genetics 26, 7–13 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A. C., Stasko M. R., Schmidt C. & Davisson M. T. Behavioral validation of the Ts65Dn mouse model for Down syndrome of a genetic background free of the retinal degeneration mutation Pde6b(rd1). Behavioural brain research 206, 52–62 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L. E. et al.. Trisomy for the Down syndrome 'critical region' is necessary but not sufficient for brain phenotypes of trisomic mice. Hum Mol Genet 16, 774–782 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. A. et al.. Spontaneous stereotypy in an animal model of Down syndrome: Ts65Dn mice. Behavior genetics 31, 393–400 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst J. L. & Beynon R. J. Scent wars: the chemobiology of competitive signalling in mice. Bioessays 26, 1288–1298 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty R. L. Odor-guided behavior in mammals. Experientia 42, 257–271 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A., Benfenati F. & Gasparini L. Communication breaks-Down: from neurodevelopment defects to cognitive disabilities in Down syndrome. Progress in neurobiology 91, 1–22 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierssen M. et al.. Alterations of central noradrenergic transmission in Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome. Brain research 749, 238–244 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockrow J. et al.. Cholinergic degeneration and memory loss delayed by vitamin E in a Down syndrome mouse model. Experimental neurology 216, 278–289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandairon N. & Linster C. Odor perception and olfactory bulb plasticity in adult mammals. J Neurophysiol 101, 2204–2209 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemdal P., Corwin J. & Oster H. Olfactory identification deficits in Down's syndrome and idiopathic mental retardation. Neuropsychologia 31, 977–984 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown D. A. et al.. Olfactory function in young adolescents with Down's syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 61, 412–414 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. Loss of olfactory function in dementing disease. Physiology & behavior 66, 177–182 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliger M., Lander T. & Murphy C. Effects of the ApoE epsilon4 allele on olfactory function in Down syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis 6, 397–402; discussion 443–399 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. & Jinich S. Olfactory dysfunction in Down's Syndrome. Neurobiology of aging 17, 631–637 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijjar R. K. & Murphy C. Olfactory impairment increases as a function of age in persons with Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging 23, 65–73 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey P. A., Malnic B. & Buck L. B. The mouse olfactory receptor gene family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 2156–2161 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck L. & Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 65, 175–187 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malnic B., Godfrey P. A. & Buck L. B. The human olfactory receptor gene family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 2584–2589 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. et al.. Functional expression of a mammalian odorant receptor. Science 279, 237–242 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland M. D. et al.. Discrimination of saturated aldehydes by the rat I7 olfactory receptor. Biochemistry 49, 6302–6304 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Howard J. D. & Gottfried J. A. Disruption of odour quality coding in piriform cortex mediates olfactory deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Brain : a journal of neurology 133, 2714–2726 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al.. Olfactory deficit detected by fMRI in early Alzheimer's disease. Brain research 1357, 184–194 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al.. In vivo MRI identifies cholinergic circuitry deficits in a Down syndrome model. Neurobiology of aging 30, 1453–1465 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. E. Activity, modulation and role of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons innervating the cerebral cortex. Progress in brain research 145, 157–169 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. E. & Yang T. Z. The efferent projections from the reticular formation and the locus coeruleus studied by anterograde and retrograde axonal transport in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology 242, 56–92 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J., Nagy J. I., Atmadia S. & Fibiger H. C. The nucleus basalis magnocellularis: the origin of a cholinergic projection to the neocortex of the rat. Neuroscience 5, 1161–1174 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick D. A. & Prince D. A. Mechanisms of action of acetylcholine in the guinea-pig cerebral cortex in vitro. The Journal of physiology 375, 169–194 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. A., Fletcher M. L. & Sullivan R. M. Acetylcholine and olfactory perceptual learning. Learning & memory 11, 28–34 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellier J. L. et al.. Olfactory discrimination varies in mice with different levels of alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression. Brain Res 1358, 140–150 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo P. E., Carleton A., Vincent J. D. & Lledo P. M. Multiple and opposing roles of cholinergic transmission in the main olfactory bulb. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 19, 9180–9191 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A., Fila T., Bartesaghi R. & Ciani E. Choline acetyltransferase activity at different ages in brain of Ts65Dn mice, an animal model for Down's syndrome and related neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of neurochemistry 97, 515–526 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capsoni S., Giannotta S. & Cattaneo A. Nerve growth factor and galantamine ameliorate early signs of neurodegeneration in anti-nerve growth factor mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99, 12432–12437 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney J. E., Puttfarcken P. S. & Coyle J. T. Galanthamine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor: a time course of the effects on performance and neurochemical parameters in mice. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior 34, 129–137 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney J. E., Bachman E. S. & Coyle J. T. Effects of different doses of galanthamine, a long-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, on memory in mice. Psychopharmacology 102, 191–200 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J. et al.. Perinatal choline supplementation improves cognitive functioning and emotion regulation in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Behavioral neuroscience 124, 346–361 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda N., Flórez J. & Martínez-Cué C. Chronic pentylenetetrazole but not donepezil treatment rescues spatial cognition in Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett 433, 22–27 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Kadir A., Forsberg A., Porras O. & Nordberg A. Long-term effects of galantamine treatment on brain functional activities as measured by PET in Alzheimer's disease patients. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 24, 109–123 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse P. J. et al.. Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science 215, 1237–1239 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akeson E. C. et al.. Ts65Dn -- localization of the translocation breakpoint and trisomic gene content in a mouse model for Down syndrome. Cytogenet Cell Genet 93, 270–276 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick B. M. & Restrepo D. in Current Protocols in Neuroscience (eds Crawley J. N., et al.) 1–24 (John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gamble K. R. & Smith D. W. Discrimination of "odorless" mineral oils alone and as diluents by behaviorally trained mice. Chemical senses 34, 559–563 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. & Crawley J. N. Simple behavioral assessment of mouse olfaction. Current protocols in neuroscience / editorial board, Jacqueline N. Crawley ...[et al.] Chapter 8, Unit 8 24 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information Galantamine improves olfactory learning in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome