Abstract

A collaborative multicenter study was conducted to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, and precision of a three-step, fully automated, qualitative microparticle-based enzyme-linked immunoassay (AxSYM HIV Ag/Ab Combo; Abbott Laboratories), designed to simultaneously detect (i) antibodies against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and/or type 2 (HIV-2) and (ii) HIV p24 antigen. A significant reduction in the HIV seroconversion window was achieved by combining detection of HIV antibodies and antigen into a single assay format. For 22 selected, commercial HIV seroconversion panels, the mean time of detection with the combined-format HIV antigen-antibody assay was reduced by 6.15 days compared to that with a similar third-generation single-format HIV antibody assay. The quantitative sensitivity of the combination assay for the p24 antigen (17.5 pg/ml by use of the p24 quantitative panel VIH SFTS96′) was nearly equivalent to that of single-format antigen tests. The combination assay demonstrated sensitive (100%) detection of anti-HIV immunoglobulin in specimens from individuals in CDC stages A, B, and C and from individuals infected with different HIV-1 group M subtypes, group O, or HIV-2. The apparent specificity for hospitalized patients (n = 1,938) was 99.90%. In a random population of 7,900 volunteer blood donors, the specificity (99.87%) was comparable to that of a third-generation single-format HIV antibody assay (99.92%) on the same donor specimens. In addition, the combination assay was robust to potential interfering specimens. The precision of the combination was high, with intra- and interrun variances of ≤9.3% for each precision panel specimen or assay control and ≤5.3% for the negative assay control.

Combined, simultaneous detection of anti-human immunodeficiency virus (anti-HIV) immunoglobulin and HIV core protein distinguishes fourth-generation (combination assay) HIV screening and diagnostic immunoassays from third-generation (double-antigen sandwich) antibody detection immunoassays (5, 6, 12, 15-18, 27, 30-32). Prior to the introduction of fourth-generation assays, commercial immunoassays for blood screening and diagnosis of HIV infection were based either on detection of HIV core (p24) protein (1, 14, 22) or on detection of HIV-specific antibodies, notably those antibodies directed against HIV transmembrane proteins (tmp). Antibodies against these proteins consistently appear during seroconversion of HIV-infected individuals and remain throughout the course of infection (2, 3, 7, 19, 24, 26). Fourth-generation immunoassays have targeted reduction of the seronegative window period to achieve a continued decrease in the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV infection (5, 6, 12, 15-17, 27, 30-32). Combining antibody and antigen detection in a single immunoassay format achieves a reduction in the seroconversion window because HIV core protein (p24) appears transiently in the blood and has been used as a marker of antigenemia prior to a detectable humoral immune response to HIV infection (1, 4, 9, 11, 13, 14, 22, 29; J. P. Phair, Editorial, JAMA 258:1218, 1987; R. Stute, Letter, Lancet i:566, 1987; R. A. Wall, D. W. Denning, and A. Amos, Letter, Lancet i:566, 1987).

Antigen (p24) testing in a combined (fourth-generation) format has been estimated to reduce the seroconversion window by a few days to as much as ∼2 weeks in comparison with third-generation single-format antibody detection assays (5, 12, 18, 25, 27, 28, 30-32). Despite enhanced seroconversion sensitivity, fourth-generation assays will be most valuable only if the specificity and sensitivity of individual antibody and antigen detection formats are not compromised when they are combined into a single immunoassay. Sensitive combination assays will need to detect antigen at levels equivalent to those of single-format antigen assays in order to be recommended as replacements for current antigen tests (5, 6, 15, 18, 32). This prerequisite, however, presents a considerable technical challenge not met by all combination assays (5, 6, 12, 15, 28). In addition, not all combined formats have achieved the low (nonconfirmed) repeat-reactive rates expected of blood donor screening and diagnostic assays that result in high specificities such as those typically displayed by third-generation single-format antibody assays (5, 12, 17, 23, 25, 32). In this report we describe a multicenter evaluation of a fourth-generation, fully automated HIV combination assay (AxSYM HIV Ag/Ab Combo MEIA [AxSYM Combo]; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.), and we demonstrate an antigen assay sensitivity approaching that of single-format antigen tests, achievement of a specificity equivalent to that of a third-generation single-format antibody assay, and a high degree of total precision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AxSYM Combo.

AxSYM Combo combines microparticle, fluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunoassay technologies into an automated, random-access system. After specimens are loaded into the instrument, AxSYM mixes serum or plasma specimens with a detergent-enriched, buffered specimen diluent formulated to disrupt HIV for optimal p24 exposure and to decrease or eliminate nonspecific or interfering reactions of undesirable plasma or serum components with the microparticles. Microparticles, the specimen dilution buffer, and the specimen are incubated together in the first step. Serum or plasma antibodies (immunoglobulin G [IgG] or IgM against the HIV tmp gp41) are captured via microparticle-bound recombinant proteins (purified after expression in Escherichia coli or Bacillus megaterium) presenting key antigenic portions of tmp representative of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) group M, HIV-1 group O, or HIV-2. Serum or plasma antigen (HIV p24 core protein) is captured via microparticle-bound monoclonal (anti-p24) antibodies. After incubation, AxSYM transfers microparticles bearing immune complexes to a porous matrix. The matrix retains the microparticles and separates microparticle-bound immune complexes from unbound serum or plasma components. After transfer, AxSYM washes the matrix to remove all unbound components or materials.

In the second step, antibody (anti-tmp) and/or antigen (p24 core antigen) sandwiches are formed by automated addition of biotinylated probes (biotinylated recombinant tmp, biotinylated peptides derived from the immunodominant regions of tmp, and biotinylated monoclonal [anti-p24] antibodies) to microparticle-bound immune complexes. Biotinylated probes are presented in a buffered diluent (probe diluent) formulated to enhance immune binding and to limit nonspecific interactions between probes and solid-phase components. After an incubation period, AxSYM washes the matrix and removes unbound materials.

In the third step, biotinylated probes bound to the solid phase via sandwich formation are reacted with an anti-biotin rabbit antibody complexed with alkaline phosphatase (conjugate) presented in a diluent formulated to enhance the formation of biotin-anti-biotin immune complexes and to limit nonspecific binding of the conjugate. After an incubation period, unbound, excess conjugate is washed away. AxSYM detects the formation of antibody (anti-tmp) and antigen (p24 core protein) immune complexes by automated addition of 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate, which is a fluorescent substrate for alkaline phosphatase. As 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate is converted to methylumbelliferone by alkaline phosphatase, AxSYM detects and quantifies the fluorescent signal. The signal is proportional to the amount of antibody (anti-tmp) or antigen (p24 core protein) contained in the original plasma or serum sample. Additional, detailed technical information is contained in the AxSYM Combo LN2G83 package insert.

The AxSYM Combo assay cutoff value (the rate units of the index calibrator plus 27.5 rate units) was determined from previous studies and was maintained throughout this study. AxSYM stores the mean rate of three index calibrator replicates, calculates the cutoff by adding 27.5 rate units, and delivers specimen results as a ratio of the specimen signal (in rate units) to the cutoff value (S/CO). S/CO ratios of ≥1 were reactive and indicated the presence of anti-HIV immunoglobulin and/or p24 antigen (markers); ratios equal to or greater than 0.90 and less than 1.0 were in the gray zone; and ratios of <0.90 were negative or nonreactive for the marker(s). AxSYM Combo reagent and control kits were made and supplied by Abbott GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany.

AxSYM gO.

AxSYM HIV [1/2] gO MEIA (AxSYM gO; Abbott Laboratories) is a three-step antibody detection assay similar to the AxSYM Combo employing the same antibody detection reagents and components. Additional, detailed technical information can be found in the AxSYM gO package insert. AxSYM gO reagent and control kits were made and supplied by Abbott GmbH & Co. KG.

Confirmatory (supplemental) assays.

New LAV Blot I and New LAV Blot II were from Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif. HIV Antigen MAB (p24 antigen test) and HIV Antigen Confirmatory were from Murex Biotech Ltd., Dartford, United Kingdom. Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor was from Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany. Commercial assays were performed according to their respective package inserts. Confirmatory testing was conducted at Abbott GmbH & Co. KG and at BioScientia, Ingelheim, Germany.

Specimens.

Human specimens used in this study were collected according to each country's relevant guidelines and each vendor's relevant institutional policies. In addition to specificity testing against specimens from random blood donors and hospital patients, AxSYM Combo was evaluated against a panel of plasma specimens (n = 319) from non-HIV-infected patients with a variety of diseases, disorders, infectious agents, or conditions which might cause inaccurate test results. These included specimens from (i) individuals with previous or current infection with hepatitis B virus (HBsAg positive) (n = 15), cytomegalovirus (n = 15), Epstein-Barr virus (n = 10), herpes simplex virus (n = 15), or hepatitis A virus (n = 15) (all from Pyramid Profile Diagnostics, Sherman Oaks, Calif.), hepatitis C virus (n = 10), human T-cell leukemia virus type I (n = 10), or human T-cell leukemia virus type II (n = 10) (all from Impath BioClinical Partners, Franklin, Mass.), or rubella virus (n = 15) (Pyramid Profile Diagnostics); (ii) individuals with previous or current infection with Candida albicans (n = 10), Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis) (n = 15), Treponema pallidum (syphilis) (n = 15), or E. coli (blood and/or urine culture positive) (n = 9) (supplied by Pyramid Profile Diagnostics [T. pallidum and T. gondii], ProMedDx [E. coli], and BioScientia [C. albicans]); (iii) individuals with rheumatoid factor (n = 12) (Uniklinikum Aachen, Aachen, Germany, and Pyramid Profile Diagnostics), anti-nuclear antibodies (n = 14) (Pyramid Profile Diagnostics), elevated levels of IgG (n = 10) or IgM (n = 10) (Millennium Biotech, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.), multiple myeloma (n = 9) or monoclonal gammopathy (n = 10) (BioClinical Partners), or HAMA (human anti-mouse antibody) (n = 10) (Scantibodies); (iv) pregnant females in the 1st (n = 26), 2nd (n = 17), or 3rd (n = 17) trimester, or multiparous females (n = 10) (supplied by BioClinical Partners [pregnant and multiparous females] and Millenium Biotech [pregnant females only]); and (v) flu vaccinees (n = 10) (supplied by Uniklinikum Aachen).

Sensitivity was determined by using the following categories of specimens: (i) 453 specimens from HIV-1-infected individuals staged to according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifications (143 at stage A, 131 at stage B, and 179 at stage C); (ii) 55 specimens from individuals infected with known HIV-1 group M subtypes (11 with subtype A, 3 with subtype B, 1 with subtype B/D, 7 with subtype C, 5 with subtype D, 6 with CRF01_A/E, 16 with subtype F, 5 with subtype G, and 1 with subtype J) (supplied by Boston Biomedica Inc., West Bridgewater, Mass., and Abbott Laboratories); (iii) 107 specimens from nonstaged individuals infected with unknown subtypes of HIV-1; (iv) 19 specimens from individuals infected with HIV-1 group O (supplied by Loeffler Institute of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany, Boston Biomedica Inc., and Abbott Laboratories), 9 of which were tested at a 1:100 dilution in normal human plasma to conserve the specimens, while all others were tested undiluted; (v) 108 specimens from individuals infected with HIV-2 living in regions of HIV-2 endemicity (supplied by Boston Biomedica Inc., Abbott Laboratories, and DiaServe Laboratories GmbH, Hamburg, Germany); (vi) 50 specimens from individuals infected with HIV-1 containing p24 antigen, half of which also contained detectable antibody against HIV-1 (supplied by Impath-BioClinical Partners, Pyramid Profile Diagnostics, Inc., and Boston Biomedica Inc.); (vii) 179 specimens from individuals with elevated risks of HIV infection, including 40 from homosexual males and 40 from individuals with a sexually transmitted disease (supplied by Millenium Biotech, Inc.), 40 specimens from intravenous drug abusers (supplied by Pyramid Profile Diagnostics Inc.), and 19 specimens from individuals with hemophilia, 10 from dialysis patients, and 30 from multiply transfused individuals (supplied by Impath-BioClinical Partners); (viii) HIV-1 seroconversion panels (designated by catalog no.) 6240, 6243, 6244, 6247, 6248, 9012, 9013, 9015, and 9028 (supplied by Impath-BioClinical Partners), PRB923, PRB924, PRB926, PRB931, PRB938, PRB940, PRB941, and PRB945 (supplied by Boston Biomedica Inc.), RP029 (supplied by Pyramid Profile Diagnostics Inc.), and SV-0400, SV-0401, SV-0403, and SV-0406 (supplied by Nabi, Boca Raton, Fla.). In addition, (ix) quantitative antigen sensitivity was estimated from linear regression analysis of panel members 2025 to 2029 from the p24 quantitative standard panel VIH SFTS96′, supplied by the French Society of Blood Transfusion.

Precision.

The assay precision was evaluated at each testing center by using controls consisting of a negative index calibrator, negative control, positive control 1 (human anti-HIV-1 plasma), positive control 2 (human anti-HIV-2 plasma), viral lysate positive control (gradient enriched, lysed HIV-1 in Tris buffer), and a proficiency panel consisting of two human anti-HIV-1 plasma specimens, two human anti-HIV-2 plasma specimens, one specimen containing a mouse monoclonal antibody (anti-HIV-1 group O tmp) in negative human plasma, and one specimen containing p24 purified from HIV-1 in negative human plasma (delivered frozen). The controls and panel samples were evaluated at 10 independent sites on 10 instruments, with the exception of the HIV-1 p24 proficiency panel member tested at 8 sites on 8 instruments. Nine sites tested two different lots of controls, and one site tested three different lots of controls. All samples were tested in triplicate over three runs. At one site, the controls and panel samples were tested on one reagent kit (clinical) lot; at eight sites, they were tested on each of two reagent kit (clinical) lots; and at one site, they were tested across four different reagent kit (clinical) lots. The within-run and between-run standard deviations (SD) and coefficients of variation (CV) were analyzed by variance component analysis using a mixed analysis of variance model (20).

Specificity and sensitivity.

Specificity was determined with samples from random blood donor populations (7,900 specimens collected from seven blood screening centers and comprising 6,352 serum samples [distributed over five testing sites] and 1,548 plasma samples [distributed over two testing sites]) and diagnostic populations (1,938 specimens collected from patients in six hospitals, with testing distributed over five sites). Specificity was defined as the percentage of HIV marker-negative specimens correctly identified as nonreactive in populations at low risk of HIV infection and was calculated as [TN/(TN + FP)] × 100, where TN (true negatives) is the number of HIV RNA- and HIV marker-negative specimens correctly identified by the AxSYM Combo as nonreactive (negative), FP (false positives) is the number of HIV RNA- and HIV marker-negative specimens incorrectly identified as repeat reactive (positive) by the AxSYM Combo, and TN + FP is the sum of all specimens in the study population (10). Specimens that were initially reactive (S/CO, ≥1.0) or initially gray zone reactive (0.9 ≤ S/CO < 1.0) in AxSYM Combo and/or AxSYM gO were retested in duplicate in both assays, and those that were repeatedly reactive and/or repeatedly gray zone reactive were analyzed by supplemental tests including the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor (ultrasensitive HIV RNA procedure), New LAV Blot I and New LAV Blot II (interpreted for the presence of antibodies against HIV according to German standard DIN 58969-41 [July 1994]), and/or HIV Antigen MAB and HIV Antigen Confirmatory (to detect HIV p24 antigen). Repeat-reactive specimens that contained detectable HIV RNA, HIV antigen, or anti-HIV immunoglobulin were confirmed as positive and omitted from the specificity calculation.

Sensitivity was defined as the percentage of HIV marker-positive specimens correctly identified as repeat reactive in pedigreed specimens containing detectable anti-HIV immunoglobulin, HIV p24 antigen, or HIV RNA and was calculated as [TP/(TP + FN)] × 100, where TP (true positives) is the number of repeat-reactive specimens containing HIV markers or HIV RNA, FN (false negatives) is the number of specimens containing at least one HIV marker incorrectly identified as nonreactive (negative), and TP + FN is the sum of all the specimens in the sensitivity study (10).

RESULTS

Precision results for the AxSYM Combo assay are recorded in Table 1. Within- and between-run SD and CV for all panel members were within expected values compared to other AxSYM assays, and all CV were less than 10%. Within- and between-run CV ranged from 4.5 to 5.3% and 5.5 to 6.6%, respectively, for kit controls (negative control, positive control 1, positive control 2, and viral lysate positive control) and from 3.7 to 7.2% and 4.6 to 9.3%, respectively, for the other proficiency panel members.

TABLE 1.

AxSYM Combo precision

| Proficiency panel member | No. of replicates | Mean S/CO | Precision

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within runs

|

Between runs

|

|||||

| SD | CV (%) | SD | CV (%) | |||

| Index calibrator | 189 | 17.10a | 0.824 | 4.8 | 0.972 | 5.7 |

| AxSYM Combo negative assay control | 414 | 0.38 | 0.017 | 4.5 | 0.021 | 5.5 |

| AxSYM Combo HIV-1-positive assay control | 414 | 3.84 | 0.205 | 5.3 | 0.253 | 6.6 |

| AxSYM Combo HIV-2 positive assay control | 414 | 3.55 | 0.166 | 4.7 | 0.219 | 6.2 |

| AxSYM Combo viral lysate positive assay control | 414 | 3.23 | 0.158 | 4.9 | 0.191 | 5.9 |

| Anti HIV-1 high titer (nondiluted) | 189 | 25.96 | 1.29 | 5.0 | 2.41 | 9.3 |

| Anti HIV-2 high titer (nondiluted) | 189 | 54.15 | 2.00 | 3.7 | 2.47 | 4.6 |

| Anti HIV-1 medium titer (diluted) | 189 | 11.85 | 0.541 | 4.6 | 0.742 | 6.3 |

| Anti HIV-2 medium titer (diluted) | 189 | 11.79 | 0.519 | 4.4 | 0.912 | 7.7 |

| Anti HIV-1 group O | 189 | 3.92 | 0.283 | 7.2 | 0.333 | 8.5 |

| HIV p24 antigenb | 162 | 1.59 | 0.068 | 4.2 | 0.102 | 6.4 |

Expressed as a rate value.

Data from one site were omitted due to errors in the preparation of the specimen.

The specificity of the AxSYM Combo was estimated in low-prevalence blood donor populations and compared to the specificity of the AxSYM gO using the identical specimens (Table 2). It is noteworthy that in the random blood donor population (n = 7,900), two AxSYM Combo repeat-reactive specimens were not initially reactive by the AxSYM Combo assay. These specimens were initially reactive by the AxSYM gO and were retested by the AxSYM Combo. The specificity of the AxSYM Combo improved from 99.87 to 99.90% when these two specimens were removed from the specificity calculations. Regardless, the specificity of the AxSYM Combo lies within the 95% specificity confidence interval for the AxSYM gO, indicating that the specificities of the two assays are statistically equivalent. The cutoff value for the AxSYM Combo was 9.8 SD from the mean of the negative (random blood donor) population, similar to that for the AxSYM gO (10.9 SD from the mean of the negative population).

TABLE 2.

AxSYM Combo specificity

| Population | n | Result(s) for:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AxSYM Combo

|

AxSYM gO

|

|||||||||

| Initial reactive ratea (no. of specimens initially reactive) | Repeat-reactive ratea (no. of repeat-reactive specimensb) | % (no.) of nonconfirmedc repeat-reactive specimens | Specificity (%) | Initial reactive ratea (no. of specimens initially reactive) | Repeat-reactive ratea (no. of repeat-reactive specimensb) | % (no.) of nonconfirmedc repeat-reactive specimens | Specificity (%) | 95% Confidence interval (%) | ||

| Random blood donorsd | 7,900 | 0.10 (8) | 0.13 (10d) | 0.13 (10d) | 99.87 (99.90d) | 0.08 (6) | 0.08 (6) | 0.08 (6) | 99.92 | 99.83-99.97 |

| Hospitalized patients | 1,938 | 0.57 (11) | 0.47 (9)e | 0.10 (2) | 99.90 | 0.57 (11) | 0.52 (10)e | 0.16 (3) | 99.84 | 99.55-99.97 |

| Total | 9,838 | 0.19 (19) | 0.19 (19) | 0.12 (12) | 99.88 (99.90d) | 0.17 (17) | 0.16 (16) | 0.09 (9) | 99.91 | 99.83-99.96 |

Expressed as a percentage, rounded to the nearest 0.01% of the total (n).

Following an initial reactive result in either the AxSYM Combo or the AxSYM gO.

Not confirmed to contain detectable levels of HIV RNA or HIV markers (anti-HIV immunoglobulin or HIV p24 antigen) by supplemental testing. Nonconfirmed repeat-reactive specimens are assay false positives. The remaining specimens in the populations are considered to be negative for HIV markers and HIV infection (true negatives).

Two specimens were initially negative by the AxSYM Combo but initially gray zone reactive by the AxSYM gO; upon restesting in both assays (per the evaluation protocol), these specimens were low-level repeat reactive in the AxSYM Combo. In a laboratory setting without special specificity protocols, these two samples would not have been identified as repeat reactive.

Seven repeat-reactive specimens were confirmed as positive for HIV RNA (1 specimen) or anti-HIV-1 immunoglobulin (6 specimens), leaving 2 (AxSYM Combo) or 3 (AxSYM gO) nonconfirmed repeat-reactive specimens for calculation of specificity.

The specificity of the AxSYM Combo also was estimated by using a higher-risk hospital (diagnostic) population (Table 2). Based on 1,938 random patient specimens, the specificity of the AxSYM Combo was 99.90%, slightly higher than that of the AxSYM gO and within the 95% confidence interval for AxSYM gO specificity in the same diagnostic population. Seven repeat-reactive specimens identified by both assays were removed from the specificity calculation because they contained detectable anti-HIV immunoglobulin or HIV RNA by methods listed previously. When all specimens (n = 9,838) were used, the specificity of the fourth-generation combination assay (99.88%) was nearly identical to the specificity of the third-generation single-format antibody assay (99.91%).

During testing of the AxSYM Combo against a panel of 319 specimens (from non-HIV-infected individuals) containing potential interfering substances, only 5 samples were identified as repeat reactive (data not shown). These specimens belonged to individuals with E. coli infection (n = 2) (S/CO, 2.8 and 4.4), rheumatoid factor (n = 1) (S/CO, 1.7), or monoclonal gammopathy (n = 2) (S/CO, 17.8 and 2.1).

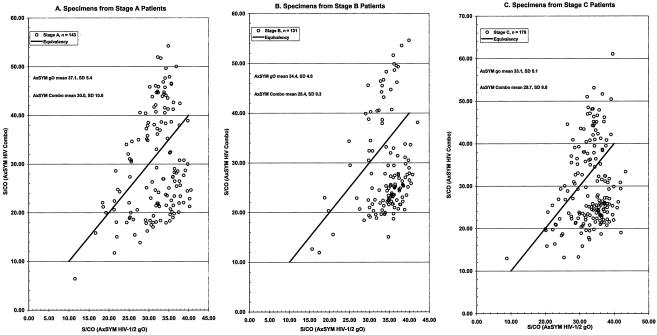

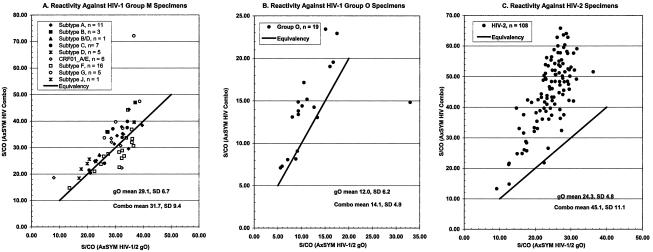

Panels of pedigreed HIV-1 and HIV-2 specimens were evaluated in order to determine the qualitative sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo compared to the AxSYM gO (Table 3). The AxSYM Combo readily detected all specimens containing anti-HIV immunoglobulin (S/CO, 6.42 to 72.11) from patients in CDC stages A, B, and C (Fig. 1A through C, respectively). These data demonstrated that the AxSYM Combo had ample sensitivity to detect HIV-1 infections (anti-HIV-1 immunoglobulin), although the means of S/CO ratios for the specimens from staged patients were slightly greater for the AxSYM gO. Additionally, specimens containing anti-HIV-1 immunoglobulin against specific group M subtypes (Fig. 2A) were slightly more reactive by the AxSYM Combo than by the AxSYM gO. Further comparisons of S/CO ratios demonstrated that specimens from individuals infected with HIV-1 group O (Fig. 2B) or HIV-2 (Fig. 2C) were more reactive by the AxSYM Combo than by the AxSYM gO. Of 25 specimens (Table 3) containing at least 25 pg of HIV antigen/ml but no antibody, all were detected at S/CO ratios ranging from 1.15 to 71.37; the remaining 25 specimens containing antigen and antibody also were reactive.

TABLE 3.

AxSYM Combo sensitivity

| Specimen descriptiona | n | No. of specimens detected by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Category | AxSYM Combo | AxSYM gO | |

| HIV-1 | ||||

| Ab | CDC stage A | 143 | 143 | 143 |

| Ab | CDC stage B | 131 | 131 | 131 |

| Ab | CDC stage C | 179 | 179 | 179 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype A | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype B | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype B/D | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype C | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype D | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Ab | Group M, CRF01_A/E | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype F | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype G | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Ab | Group M, subtype J | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ab | Group O | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Ag ± Abb | HIV p24 antigen | 50 | 50 | 25 |

| Ab | Unknown subtype | 107 | 107 | 107 |

| HIV-2, Ab | Unknown subtype | 108 | 108 | 108 |

| All markers | All specimens | 792 | 792 | 767 |

Pedigreed specimens containing antibody (Ab) against HIV-1 or HIV-2 and/or HIV-1 p24 antigen (Ag). Specimens were from diverse geographical regions including Arabia, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Cameroon, China, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Ghana, Great Britain, Ivory Coast, Iran, Italy, Kenya, Korea, Mozambique, The Netherlands, Nigeria, Poland, Romania, Spain, Syria, Thailand, Togo, Turkey, Uganda, the United States, Zaire, and Zimbabwe.

All specimens contained detectable levels of HIV-1 p24 antigen estimated to be in excess of 25 pg/ml. Half of these specimens also contained detectable antibody.

FIG. 1.

Evaluation of the qualitative antibody sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo compared to that of the AxSYM gO by using pedigreed specimens from HIV patients at different CDC stages.

FIG. 2.

Evaluation of the qualitative antibody sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo compared to that of the AxSYM gO by using pedigreed specimens from individuals infected with HIV-1 group M (A), HIV-1 group O (B), or HIV-2 (C).

A panel of 179 random specimens collected from individuals at high risk for HIV infection was tested in order to further assess the qualitative sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo compared to that of the AxSYM gO (Table 4). Perfect concordance between the assays was observed because the same 42 LAV Blot I (Western blot)-confirmed positive specimens were identified by each assay. Reactive samples were represented as follows: homosexual males (29 of 40), individuals with sexually transmitted diseases (5 of 40), hemophiliacs (6 of 19), and multiply transfused individuals (2 of 30).

TABLE 4.

Concordance between the AxSYM Combo and the AxSYM gO in a high-risk population

| AxSYM gO result | No. of specimens with the following AxSYM Combo result:

|

Total no. of specimens | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonreactive | Repeat reactive | ||

| Nonreactive | 137 | 0 | 137 |

| Repeat reactive | 0 | 42 | 42 |

| Total | 137 | 42 | 179 |

The seroconversion sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo was assessed against 22 commercial HIV-1 seroconversion panels (Table 5) and compared with that of the AxSYM gO. In the seroconversion panels selected for this study, the mean time delay (days) from detection of an HIV marker (antigen and/or antibody) with the AxSYM Combo to detection with the AxSYM gO was 6.15 days, and the longest delay was 20 days. The AxSYM Combo was reactive 1 to 2 bleeds earlier than the AxSYM gO for 18 of 22 panels and was equally reactive in 4 of 22 panels. In addition, a detailed inspection of results from three selected seroconversion panels (Table 6) demonstrated that the antigen-driven seroconversion sensitivity of AxSYM the Combo often was equivalent to that of single-format antigen tests. In other selected seroconversion panels, specimens containing p24 antigen (and no detectable antibody) were reactive in the AxSYM Combo 1 bleed date later than in an antigen test.

TABLE 5.

AxSYM Combo seroconversion sensitivity

| Commercial supplier and HIV panel | No. of days after first blood draw (no. of reactive panel members)

|

Time delaya (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AxSYM Combo | AxSYM gO | ||

| BCP 6240 | 23 (6) | 28 (5) | 5 |

| BCP 6243 | 25 (4) | 32 (2) | 7 |

| BCP 6244 | 28 (3) | 33 (2) | 5 |

| BCP 6247 | 23 (3) | 30 (1) | 7 |

| BCP 6248 | 18 (2) | 25 (1) | 7 |

| BCP 9012 | 16 (3) | 21 (2) | 5 |

| BCP 9013 | 25 (1) | NDb | ND |

| BCP 9015 | 28 (4) | 35 (2) | 7 |

| BCP 9028 | 53 (2) | ND | ND |

| BBI PRB 923 | 37 (6) | 47 (5) | 10 |

| BBI PRB 924 | 26 (4) | 33 (3) | 7 |

| BBI PRB 926 | 7 (4) | 27 (2) | 20 |

| BBI PRB 931 | 28 (4) | 28 (4) | 0 |

| BBI PRB 938 | 0 (3) | 9 (1) | 9 |

| BBI PRB 940 | 7 (7) | 11 (6) | 4 |

| BBI PRB 941 | 18 (3) | 18 (3) | 0 |

| BBI PRB 945 | 13 (3) | 13 (3) | 0 |

| Nabi SV-0400 | 12 (4) | 23 (2) | 11 |

| Nabi SV-0401 | 7 (5) | 11 (4) | 4 |

| Nabi SV-0403 | 0 (4) | 10 (3) | 10 |

| Nabi SV-0406 | 6 (3) | 11 (2) | 5 |

| Pyr RP029 | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 0 |

| Total bleeds detected | (93) | (68) | |

| Mean time delay | 6.15c | ||

| Maximum delay detected | 20 | ||

Days between serial seroconversion bleeds from the point of detection with the AxSYM Combo to detection with the AxSYM gO.

ND, not detected. The AxSYM gO failed to detect all members of the panel.

Data from panels BCP 9013 and BCP 9028 were not included because the AxSYM gO failed to detect all members of the panel. Estimation of mean time delay is dependent on selection of seroconversion panels and method of comparison.

TABLE 6.

AxSYM Combo performance on selected seroconversion panels

| Vendora | Panel ID | Bleed no. | Bleed date | Days after 1st bleed | AxSYM Combob

|

AxSYM gO

|

HIV-1 Western blot resultd,e | HIV Ag S/COd | HIV RNA NAT, copies/ml or resultd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLb | S/CO | Resultc | S/CO | Resultc | ||||||||

| Nabi | SV-0401 | A | 7 Nov. 1996 | 0 | 80062 | 0.47 | − | 0.34 | − | Ind | 0.27 | 484 |

| B | 11 Nov. 1996 | 4 | 0.55 | − | 0.33 | − | Ind | 0.48 | 19,427 | |||

| C | 14 Nov. 1996 | 7 | 1.30 | REA | 0.36 | − | Ind | 2.57f | 88,176 | |||

| D | 18 Nov. 1996 | 11 | 6.80 | REA | 2.25 | REA | Ind | 9.36 | >750,000 | |||

| E | 21 Nov. 1996 | 14 | 12.16 | REA | 6.79 | REA | Ind | 12.06 | >750,000 | |||

| F | 25 Nov. 1996 | 18 | 6.73 | REA | 9.96 | REA | Pos | 2.42 | 208,979 | |||

| G | 29 Nov. 1996 | 22 | 5.60 | REA | 8.61 | REA | Pos | 1.47 | 167,423 | |||

| BBI | PRB 926 | 01 | 10 Feb. 1994 | 0 | 80065 | 0.30 | − | 0.42 | − | Neg | 0.3 | Neg |

| 02 | 12 Feb. 1994 | 2 | 0.37 | − | 0.54 | − | Neg | 0.3 | Pos | |||

| 03 | 17 Feb. 1994 | 7 | 2.44 | REA | 0.46 | − | Neg | 1.6g | Pos | |||

| 04 | 19 Feb. 1994 | 9 | 23.75 | REA | 0.39 | − | Neg | 10.5 | Pos | |||

| 05 | 9 Mar. 1994 | 27 | 8.30 | REA | 10.73 | REA | Pos | 0.5 | Pos | |||

| 06 | 14 Mar. 1994 | 32 | 8.16 | REA | 10.12 | REA | Pos | 0.5 | Pos | |||

| BCP | 6243 | 01 | 22 Aug. 1996 | 0 | 86152 | 0.42 | − | 0.43 | − | No band | 0.091 | <400 |

| 02 | 27 Aug. 1996 | 5 | 0.41 | − | 0.42 | − | p66 | 0.091 | <400 | |||

| 03 | 29 Aug. 1996 | 7 | 0.44 | − | 0.40 | − | p66 | 0.076 | <400 | |||

| 04 | 3 Sep. 1996 | 12 | 0.42 | − | 0.49 | − | p66 | 0.091 | <400 | |||

| 05 | 9 Sep. 1996 | 18 | 0.38 | − | 0.45 | − | p66 | 0.076 | 1,180 | |||

| 06 | 11 Sep. 1996 | 20 | 0.45 | − | 0.45 | − | p66 | 0.091 | 3,930 | |||

| 07 | 16 Sep. 1996 | 25 | 1.32 | REA | 0.54 | − | p66 | 1.424f | 265,000 | |||

| 08 | 18 Sep. 1996 | 27 | 1.66 | REA | 0.72 | − | p66 | 1.348 | 413,000 | |||

| 09 | 23 Sep. 1996 | 32 | 8.81 | REA | 6.95 | REA | p66 | 0.970 | 295,000 | |||

| 10 | 25 Sep. 1996 | 34 | 9.92 | REA | 8.70 | REA | p24, p66 | 1.667 | 447,000 | |||

BBI, Boston Biomedica Inc.; BCP, BioClinical Partners.

Three manufactured master lots (ML) of AxSYM Combo are represented.

S/CO ratios of >1.0 were considered reactive (REA). −, nonreactive.

Vendor data.

Ind, indeterminate; Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

Coulter HIV-1 Ag assay.

Abbott HIV-1 Ag assay.

Quantitative HIV-1 p24 antigen sensitivity was evaluated by using an HIV antigen panel (VIH SFTS96′) across three different manufactured lots of reagents. Although the S/CO ratios for all quantitative panel members (2023 to 2029) are shown in Table 7, only panel members 2025 to 2029 were used in a linear regression analysis to determine the quantitative sensitivity for each clinical reagent lot at an S/CO ratio of 1.0. The average sensitivity of the three lots was 17.5 pg of p24 antigen/ml of plasma. In addition, equivalent detection of group M subtype p24 (subtypes A, B, C, D, F, and G) and group O p24 has been reported elsewhere (16).

TABLE 7.

AxSYM Combo p24 antigen analytical sensitivitya

| VIH SFTS96′ panel member | HIV-1 p24 concn (pg/ml) | S/CO for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical reagent lot 1 | Clinical reagent lot 2 | Clinical reagent lot 3 | ||

| S2023 | 500 | 14.85 | 16.70 | 14.54 |

| S2024 | 250 | 8.95 | 9.43 | 7.00 |

| S2025 | 100 | 3.91 | 4.15 | 3.22 |

| S2026 | 50 | 2.23 | 2.30 | 1.64 |

| S2027 | 25 | 1.35 | 1.45 | 1.16 |

| S2028 | 10 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.71 |

| S2029 | 5 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.57 |

Sensitivity values 16.7, 14.5, and 21.2 pg/ml for clinical reagent lots 1 through 3, respectively, were derived from linear regression analysis of panel members S2025 to S2029 in a plot of S/CO versus p24 concentration at the point where S/CO is equal to 1. Correlation coefficients (R2) for linear regression analysis were 0.9987 for clinical reagent for lot 1, 0.9993 for clinical reagent lot 2, and 0.9935 for clinical reagent lot 3.

DISCUSSION

The fourth-generation HIV combination assay described in this report (AxSYM Combo) meets sensitivity, specificity, and precision requirements that permit safe and effective detection of sera or plasma from HIV-infected individuals. Individual antibody and antigen detection formats have been combined into a single immunoassay exhibiting an antibody sensitivity equivalent to that of third-generation single-format HIV antibody assays and an antigen sensitivity nearly equal to that of single-format antigen tests. The combined-format assay accelerates detection of HIV infection by 6.15 days within the seroconversion window period defined by seroconversion panels selected for these studies. The assay is designed to detect p24 antigen prior to seroconversion (in the absence of p24 antibody and p24 antibody-p24 antigen immune complexes), with a seroconversion window that is reduced compared to those of assays that detect only antibodies elicited against HIV.

The quantitative antigen sensitivity of the combined immunoassay was estimated at 17.5 pg of p24/ml of plasma, a value closely approaching that of single-format antigen detection assays evaluated in a study by Laperche et al. (15). In contrast to the antigen sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo, the authors (15) noted that other combined-format assays were manyfold less sensitive (65 to 250 pg/ml) than the single-antigen detection formats (8 to 15.7 pg/ml). Of course, comparisons of quantitative sensitivity are primarily dependent on the quantitative standard, and for that reason we selected the “Ag VIH SFTS96′” panel (French Society of Blood Transfusion) for our studies. The antigen sensitivity of commercial combination assays often is lower than standards set by current single-format antigen assays (8, 15, 18, 21). Delforge et al. (8) noted significant differences in the reactivities of commercially available combination assays against a patient specimen apparently containing a high level of p24 antigen (1,600 pg/ml), resulting in one selected combination assay producing a false-negative result. Further, the study (8) noted that one combination assay may be even less sensitive than third-generation single-format antibody detection assays. Additionally, Mukadi et al. (21) noted that a third-generation single-format antibody detection assay (AxSYM gO) was more sensitive than an unrelated commercial combination assay. These observations emphasize the sensitivity issues that may arise when individual antigen and antibody formats are combined into a single format (28). Although antigen sensitivity is of particular value because it is the key driver of seroconversion sensitivity (5, 6, 8, 12, 15, 18, 25, 27, 28, 30-32), antibody sensitivity must be maintained in order to detect specimens that may contain barely detectable levels of antibody or very low levels of both antibody and antigen. Sensitivity is the most important performance characteristic of an HIV screening or diagnostic assay, and it should not be compromised for any reason.

The reduction in the seroconversion window achieved with the AxSYM Combo was consistent with sensitive (17.5 pg/ml) antigen detection. Close inspection of the commercial seroconversion panels (and their associated vendor data) selected for this study revealed that in 17 of 22 (77%) seroconversion panels, the combined immunoassay was reactive against the earliest positive bleed detected by a single-format antigen (or antibody) assay, and the mean time delay between a sensitive antibody assay (the AxSYM gO) and the AxSYM Combo was 6.15 days. The data clearly demonstrate that the combined format detects specimens from HIV-antigenemic seronegative individuals and therefore reduces the risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV infection due to seronegative donations during the window period. The mean time delay (6.15 days) is in agreement with the findings of several other reports examining HIV combination assays (5, 12, 15, 18, 25, 27, 28, 30-32). However, estimations of mean time delay are dependent on the seroconversion panels selected, particularly the time intervals between collection of specimens, and the comparative tests employed. Ly et al. (16, 18) and others (6, 15, 30-32) have attempted to provide a frame of reference across multiple seroconversion panels and multiple HIV combination assays, including the AxSYM Combo. Comparisons between combination assays are most meaningful when identical seroconversion panels are evaluated across assays run concurrently.

It is noteworthy that Ly et al. (16) reported the AxSYM Combo to be sensitive for (p24) antigen from multiple HIV-1 group M subtypes. Remarkably, the AxSYM Combo displayed little or no difference in antigen sensitivity across group M and group O isolates. In contrast, one selected commercial HIV combination assay was specifically insensitive to antigen from an HIV-1 subtype C isolate, and a second combination assay was generally less sensitive than the AxSYM Combo against antigens from group M subtype isolates and was specifically insensitive to antigen from a group O isolate (16). Future improvements to estimations of antigen sensitivity across subtypes and groups of HIV-1 should include quantitative standards for each (p24) antigen.

Antibody sensitivity in the combined format was equivalent to or better than that of a related, sensitive, third-generation single-format antibody assay, the AxSYM gO. Significantly, the reactivities of specimens containing immunoglobulin elicited against HIV-1 group O and HIV-2 were greater in the AxSYM Combo than in the AxSYM gO, representing an improvement of antibody sensitivity in the combined format over that in the third-generation single-format antibody assay. The combined immunoassay readily detected all specimens from individuals infected with known or unknown HIV-1 group M subtypes and from patients in CDC stages A, B, and C. Reactivities for all samples were in excess of an S/CO ratio of 10.0, with the single exception of one strongly reactive specimen with an S/CO ratio of 6.42. These data are consistent with the observations of Ly et al. (16) indicating that the antibody sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo is equal to or greater than the antibody sensitivity of multiple other commercial HIV combination assays, particularly for specimens from individuals infected with HIV-2 or HIV-1 group O. The antibody sensitivity of the AxSYM Combo is consistent with the goal of maintaining sensitivity as the single most important performance characteristic of an HIV screening or diagnostic assay.

The specificities of the combined format for blood donor (99.87%) and diagnostic (99.90%) populations were nearly equivalent and met or exceeded the specificity characteristics usually associated with third-generation single-format antibody assays. In diagnostic populations, the AxSYM Combo outperformed the AxSYM gO, and the specificity of the combined format (99.90%) fell into the high end of the 95% confidence interval (99.55 to 99.97%) bracketing the specificity of the single-format antibody assay. In blood donors, the specificity of the AxSYM Combo was statistically equivalent to that of the AxSYM gO and fell into a narrow 95% confidence interval (99.83 to 99.97%) bracketing the specificity of the AxSYM gO. Only an additional 5 repeat-reactive specimens would be identified among 10,000 donor specimens when the combined format rather than the single-antibody format was used. The AxSYM Combo is an appropriate screening method for low-incidence populations (blood donors) because of the low rate of potential deferrals (the percentage of repeat false-reactive results was 0.13% among blood donors), and it is an appropriate diagnostic assay for higher-risk populations because of the low rate of false-reactive results (0.10% in a diagnostic population) coupled with excellent sensitivity and a high positive predictive value (10). In contrast, Ly et al. (17) observed 99.51% specificity (29,657 specimens) for a commercial diagnostic combination assay in a survey performed with consecutive and unselected French samples in public and private laboratories. Numerous other reports indicate that the specificities of HIV combination assays appear to vary significantly (5, 12, 17, 23, 25, 28, 31, 32). HIV combination immunoassays may suffer from a lack of specificity because each of the two individual formats (antigen detection or antibody detection) may elicit different negative population profiles (means and SD), may require different cutoff values for optimal sensitivity and specificity, and must necessarily utilize more reagents (e.g., antigens and monoclonal antibodies) in the combined format, providing additive contributions to nonspecific binding (12, 33; unpublished data). These factors must be reconciled in the combined format in order to achieve a specificity equivalent to or better than that of third-generation single-format antibody assays.

The AxSYM Combo is a highly sensitive, specific, and reproducible fourth-generation test that provides a clear sensitivity advantage over third-generation single-format antibody assays. Technical factors that may cause combination assays to be less sensitive or less specific than single-format assays have been overcome, resulting in an assay with a specificity suitable for screening (99.87%) or diagnostic (99.90%) purposes, an antigen sensitivity approaching that of single-format antigen tests, and an antibody sensitivity equivalent to that of a related third-generation HIV antibody assay. The AxSYM Combo received the EC Design Examination Certificate on 22 March 2002.

Acknowledgments

The following members of the AxSYM Clinical Study Group participated in this study: Snežna Levičnik-Stezinar, Blood Transfusion Center of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovenia; Rüttger Averdunk, Auguste Viktoria Krankenhaus, Berlin, Germany; Michael Elgas, Medizinisches-Diagnostisches Institut, Städtisches Klinikum Karlsruhe GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany; Sveinn Gudmundsson, Blood Bank of the National University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland; Sheila Cameron, Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow, Scotland; Gulja Willnauer, Institut für Klinische Immunologie & Transfusionsmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Leipzig AöR, Leipzig, Germany; Giovanni Landucci, Lucca Ospedale Civile, Lucca, Italy; Michaela Macri, Azienda Ospedalira “A. Cardarelli,” Naples, Italy; and Michèle Maniez- Montreuil, EFS Nord de France, Lille, France.

We thank L. Gurtler (Friedrich Loeffler Institute for Medical Microbiology, Griefswald, Germany), L. Kaptue (Département d'Hématologie, Université de Yaoundé, Yaoundé, Cameroon), and L. Zekeng (Laboratoire de Santé Hygiène Mobile, Yaoundé, Cameroon) for kindly providing us with specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allain, J. P., Y. Laurian, D. A. Paul, and D. Senn. 1986. Serological markers in early stages of human immunodeficiency virus infection in haemophiliacs. Lancet ii:1233-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan, J. S., J. E. Coligan, F. Barin, M. F. McLane, J. G. Sodroski, C. A. Rosen, W. A. Haseltine, T. H. Lee, and M. Essex. 1985. Major glycoprotein antigens that induce antibodies in AIDS patients are encoded by HTLV-III. Science 228:1091-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barin, F., M. F. McLane, J. S. Allan, T. H. Lee, J. E. Groopman, and M. Essex. 1985. Virus envelope protein of HTLV-III represents major target antigen for antibodies in AIDS patients. Science 228:1094-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen, P. A., S. A. Lobel, R. J. Caruana, M. S. Leffell, M. A. House, J. P. Rissing, and A. L. Humphries. 1988. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by transplantation: clinical aspects and time course analysis of viral antigenemia and antibody production. Ann. Intern. Med. 108:46-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brust, S., H. Duttmann, J. Feldner, L. Gurtler, R. Thorstensson, and F. Simon. 2000. Shortening of the diagnostic window with a new combined HIV p24 antigen and anti-HIV-1/2/O screening test. J. Virol. Methods 90:153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courouce, A.-M., and the Groupe de Travail Retrovirus de la S.F.T.S. 1999. Tests de depistage combine des anticorps anti-VIH et de l'antigene p24. Gazette Transfus. 155:4-17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson, G. J., J. S. Heller, C. A. Wood, R. A. Gutierrez, J. S. Webber, J. C. Hunt, S. A. Hojvat, D. Senn, S. G. Devare, and R. H. Decker. 1988. Reliable detection of individuals seropositive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) using Escherichia coli-expressed HIV structural proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 157:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delforge, M.-L., N. Dolle, P. Hermans, and C. Liesnard. 2002. Delayed HIV primary infection diagnosis with a fourth-generation HIV assay. AIDS 16:128-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devare, S. G., S. M. Desai, G. J. Dawson, H. Hampl, and J. C. Hunt. 1990. Diagnosis and monitoring of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection, p. 105-121. In N. C. Khan and J. L. Melnick (ed.), Monographs in virology, vol. 18. Human immunodeficiency virus: innovative techniques for isolation and identification. S. Karger, Basel, Switzerland.

- 10.George, R., and G. Schochetman. 1994. Detection of HIV infection using serologic techniques, p. 62-102. In G. Schochetman and R. George (ed.), AIDS testing: a comprehensive guide to technical, medical, social, legal, and management issues. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Goudsmit, J., F. de Wolf, D. A. Paul, L. G. Epstein, J. M. Lange, W. J. Krone, H. Speelman, E. C. Wolters, J. Van der Noordaa, and J. M. Oleske. 1986. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus antigen (HIV-Ag) in serum and cerebrospinal fluid during acute and chronic infection. Lancet ii:177-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurtler, L., A. Muhlbacher, U. Michl, H. Hofmann, G. G. Paggi, V. Bossi, R. Thorstensson, R. G. Villaescusa, A. Eiras, J. M. Hernandez, W. Melchior, F. Donie, and B. Weber. 1998. Reduction of the diagnostic window with a new combined p24 antigen and human immunodeficiency virus antibody screening assay. J. Virol. Methods 75:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenny, C., J. Parkin, G. Underhill, N. Shah, B. Burnell, E. Osborne, and D. J. Jeffries. 1987. HIV antigen testing. Lancet i:565-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler, H. A., B. Blaauw, J. Spear, D. A. Paul, L. A. Falk, and A. Landay. 1987. Diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection in seronegative homosexuals presenting with an acute viral syndrome. JAMA 258:1196-1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laperche, S., M. Maniez-Montreuil, and A. M. Courouce. 2000. Les tests de depistage combine de l'antigene p24 et des anticorps anti-VIH dans l'infection precoce a VIH-1. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 7(Suppl. 1):18-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ly, T. D., L. Martin, D. Daghfal, A. Sandridge, D. West, R. Bristow, L. Chalouas, X. Qiu, S. C. Lou, J. C. Hunt, G. Schochetman, and S. G. Devare. 2001. Seven human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigen-antibody combination assays: evaluation of HIV serconversion sensitivity and subtype detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3122-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ly, T. D., C. Edlinger, and A. Vabret. 2000. Contribution of combined detection assays of p24 antigen and anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies in diagnosis of primary HIV infection by routine testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2459-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ly, T. D., S. Laperche, and A. M. Courouce. 2001. Early detection of human immunodeficiency virus infection using third- and fourth-generation screening assays. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montagnier, L., F. Clavel, B. Krust, S. Chamaret, F. Rey, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and J. C. Cherman. 1985. Identification and antigenicity of the major envelope glycoprotein of lymphadenopathy-associated virus. Virology 144:283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery, D. C. 1991. Design and analysis of experiments, 3rd ed. J. Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 21.Mukadi, B. K., B. Vandercam, M. Bodeus, M. Moreau, and P. Goubau. 2002. An HIV seroconversion case: unequal performance of combined antigen/antibody assays. AIDS 16:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul, D. A., L. A. Falk, H. A. Kessler, R. M. Chase, B. Blaauw, D. S. Chudwin, and A. L. Landay. 1987. Correlation of serum HIV antigen and antibody with clinical status in HIV-infected patients. J. Med. Virol. 22:357-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portincasa, P., R. Grillo, P. Pauri, M. G. Colao, P. P. Valcavi, D. Speziale, G. Mazzarelli, E. De Majo, P. E. Varaldo, G. Fadda, C. Chezzi, and G. Dettori. 2000. Multicenter evalution of the new HIV Duo assay for simultaneous detection of HIV antibodies and p24 antigen. Microbiologica 23:357-365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarngadharan, M. G., M. Popovic, L. Bruch, J. Schupbach, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Antibodies reactive with human T-lymphotropic retroviruses (HTLV III) in the serum of patients with AIDS. Science 224:506-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saville, R. D., N. T. Constantine, F. R. Cleghorn, N. Jack, C. Bartholomew, J. Edwards, P. Gomez, and W. A. Blattner. 2001. Fourth-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the simultaneous detection of human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2518-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz, T. F., J. M. Aschauer, P. Hengster, C. Larcher, H. Wachter, B. Fleckenstein, and M. P. Dierich. 1986. Envelope gene-derived recombinant peptide in the serodiagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Lancet ii:111-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Binsbergen, J., A. Siebelink, A. Jacobs, W. Keur, F. Bruynis, M. van de Graff, J. van der Heijden, D. Kambel, and J. Toonen. 1999. Improved performance of seroconversion with a fourth generation HIV antigen/antibody assay. J. Virol. Methods 82:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Binsbergen, J., W. Keur, A. Siebelink, M. van de Graaf, A. Jacobs, D. de Rijk, L. Nijholt, J. Toonen, and L. G. Gurtler. 1998. Strongly enhanced sensitivity of a direct anti-HIV-1/-2 assay in seroconversion by incorporation of HIV p24 Ag detection: a new generation Vironostika HIV Uni-Form II. J. Virol. Methods 76:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Sydow, M., H. Gaines, A. Sonnerborg, M. Forsgren, P. O. Pherson, and O. Strannegrad. 1988. Antigen detection in primary HIV infection. Br. Med. J. 296:238-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber, B., E. H. M. Fall, A. Berger, and H. W. Doerr. 1998. Reduction of diagnostic window by new fourth-generation human immunodeficiency virus screening assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2235-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber, B., A. Berger, H. Rabenau, and H. W. Doerr. 2002. Evaluation of a new combined antigen and antibody human immunodeficiency virus screening assay, Vidas HIV Duo Ultra. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1420-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber, B., L. Gurtler, R. Thorstensson, U. Michl, A. Muhlbacher, P. Burgisser, R. Villaescusa, A. Eiras, C. Gabriel, H. Stekel, S. Tanprasert, S. Oota, M.-J. Silvestre, C. Marques, M. Ladeira, H. Rabenau, A. Berger, U. Schmitt, and W. Melchior. 2002. Multicenter evaluation of a new automated fourth-generation human immunodeficiency virus screening assay with a sensitive antigen detection module and high specificity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1938-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber, B. 2000. Authors' reply. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2460-2461. [Google Scholar]