Abstract

Objective

To synthesize the published research pertaining to breastfeeding establishment and outcomes among late preterm infants and to describe the state of the science on breastfeeding within this population.

Data Sources

Online databases Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, and reference lists of reviewed articles.

Study Selection

Nine data-based research articles examining breastfeeding patterns and outcomes among infants born between 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation or overlapping with this time period by at least two weeks.

Data Extraction

Effect sizes and descriptive statistics pertaining to breastfeeding initiation, duration, exclusivity, and health outcomes among late preterm breastfed infants.

Data Synthesis

Among late preterm mother-infant dyads, breastfeeding initiation appears to be approximately 59-70% (U.S.), while the odds of breastfeeding beyond four weeks or to the recommended six months appears to be significantly less than for term infants, and possibly less than infants ≤ 34-35 weeks gestation. Breastfeeding exclusivity is not routinely reported. Re-hospitalization, often related to “jaundice” and “poor feeding,” is nearly twice as common among late preterm breastfed infants as breastfed term or non-breastfed late preterm infants. Barriers to optimal breastfeeding in this population are often inferred from research on younger preterm infants, and evidence-based breastfeeding guidelines are lacking.

Conclusions

Late preterm infants are at greater risk for breastfeeding-associated re-hospitalization and poor breastfeeding establishment compared to their term (and possibly early preterm) counterparts. Contributing factors have yet to be investigated systematically.

Keywords: prematurity, premature birth, late preterm, breast feeding, lactation, morbidity

Background

Late preterm infants—those born between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks gestation—account for nearly three-quarters of preterm births in the United States and are the fastest growing cohort of premature infants (Davidoff et al., 2006; Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2007; Martin et al., 2007). In 2005, there were nearly 375,000 late preterm births. This figure corresponds to a dramatic increase in the incidence of late prematurity within the past two decades in the U.S.— by 25% from 1990 to 2005, and by 9.6% between only 2000 and 2005 (Martin et al., 2007). In contrast, the percentage of infants ≥ 40 weeks of gestation has decreased by 15% since 1990, and infants born before 34 weeks of gestation have increased only moderately—by 8.5% from 1990 to 2005 (Davidoff et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2007). A number of inter-related factors, including increases in the number of multiple births, the national obesity epidemic and related fetal macrosomia, the trend toward later-life childbearing, consumer demand and preferences for elective inductions and cesarean births, proliferation of obstetric malpractice litigation, practice guidelines opposing post-term deliveries, and advancements in fetal monitoring have been implicated in regard to the recent pervasiveness of late prematurity (Engle & Kominiarek, 2008; Fuchs & Gyamfi, 2008; Raju, 2006).

In concordance with the growing late preterm population, a study utilizing Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from the federal Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project revealed that non-extreme preterm infants (28 0/7-36 6/7 weeks of gestation) consume two-thirds of all hospital expenditures related to prematurity (Russell et al., 2007). The authors postulate that these expenses are attributable mainly to late preterm infants, in direct proportion to their prevalence, rather than acuity of illness. A cost analysis performed through a review of 185 near-term and full-term infants’ electronic medical records showed that near-term infants (35 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation) consume a mean of $2,630 more in medical costs than infants ≥ 37 weeks gestation (Wang, Dorer, Fleming, & Catlin, 2004).

Despite appearances and weights often comparable to their term counterparts, late preterm infants tend to lag behind in terms of their cardiorespiratory, metabolic, immunologic, neurologic, and motor development (Engle, Tomashek, & Wallman, 2007). In recognition of this contradiction, a multidisciplinary expert panel assembled by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in 2005 made the recommendation to classify infants born between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks gestation as “late preterm,” rather than “near term,” in order to convey the medical vulnerability extant within this cohort (Raju, Higgins, Stark, & Leveno, 2006). Consistent with this assertion (but not with terminology), a medical record review reported that near-term infants were four times more likely than term infants to be diagnosed with jaundice, respiratory distress, poor feeding, temperature instability, or hypoglycemia during the birth hospitalization (Wang et al., 2004). The most common of these complications were jaundice (54%), suspected sepsis (37%), and feeding difficulties (32%).

Another medical record analysis, which included more than 33,000 infants born at seven different Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program facilities, found that late preterm infants not admitted to the NICU were more likely than infants of all other gestational ages to be readmitted to the hospital within 2 weeks (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.10, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.38-4.02) (Escobar et al., 2005). The most frequent reasons for re-hospitalization were jaundice (34%) and feeding difficulties (26%). Another study by the same authors found that a gestational age of 36 weeks was one of only three predictors of re-hospitalization at 15 to 182 days following discharge (Cox hazard ratio = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.23-2.25) (Escobar, Clark, & Greene, 2006). Most recently, a chart review of more than 200,000 deliveries between 2002-2008 in the U.S. revealed that late preterm infants were significantly more likely than term infants to develop respiratory morbidity, including respiratory distress syndrome (AOR of RDS at 34 weeks compared to 39-40 weeks gestation = 40.1, 95% CI: 32.0-53.3) (The Consortium on Safe Labor, 2010).

Kramer et al. (2000) and Khashu, Narayanan, Bhargava, and Osiovich (2009) report significant mortality risks for infants considered mild or moderately preterm (32 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation) and “late preterm” (unconventially defined as 33 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation), respectively. In the Kramer et al. study (2000), the corresponding etiological fraction of mortality for moderately preterm infants exceeded those of very preterm infants (28-31 6/7 weeks gestation), while the Khashu et al. (2009) study noted significantly higher perinatal (RR = 8.0, 95% CI: 6.2-10.4), neonatal (RR = 5.5, 95% CI: 3.4-8.9), and infant mortality (RR = 3.5, 95% CI: 2.5-5.1) in late preterm as compared to term infants. Analogously, a 2008 committee publication by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reported that late preterm infants have a mortality rate 4.6 times that of term infants, a figure that has increased gradually since 1995 (Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2008).

Of particular concern, late preterm infants who are breastfed tend to be re-admitted to the hospital with diagnoses of failure to thrive, jaundice, and dehydration more frequently than those who are not breastfed, a finding largely attributed to insufficient breast milk intake (Escobar et al., 2002; Gartner, 2001; Shapiro-Mendoza et al., 2006; Tomashek et al., 2006). This trend is disconcerting, considering the many, significant, and empirically-validated advantages that breastfeeding provides, particularly for infants born prematurely (Callen & Pinelli, 2005). The purpose of this paper is to address this paradox through synthesis of the available evidence on breastfeeding-associated infant re-hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality and rates of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity/supplementation within the late preterm population. A secondary objective is to describe the state of the science on breastfeeding among late preterm mother-infant dyads, including benefits and barriers to breastfeeding and current breastfeeding recommendations. The latter objective will be achieved through review of expert opinion and clinical review papers, as data-based research is currently lacking in this area.

Methods

Electronic databases including CINAHL, Ovid MEDLINE, and PubMed, as well as the reference lists of reviewed articles were searched for English language, data-based research studies published between 1990-2010 examining breastfeeding patterns and outcomes among human infants of gestations spanning or falling within the late preterm classification (34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks gestation) by at least two weeks. Studies conducted in developing countries were excluded due to differences in breastfeeding rates, healthcare delivery, infant morbidity and mortality, and other cultural variations.

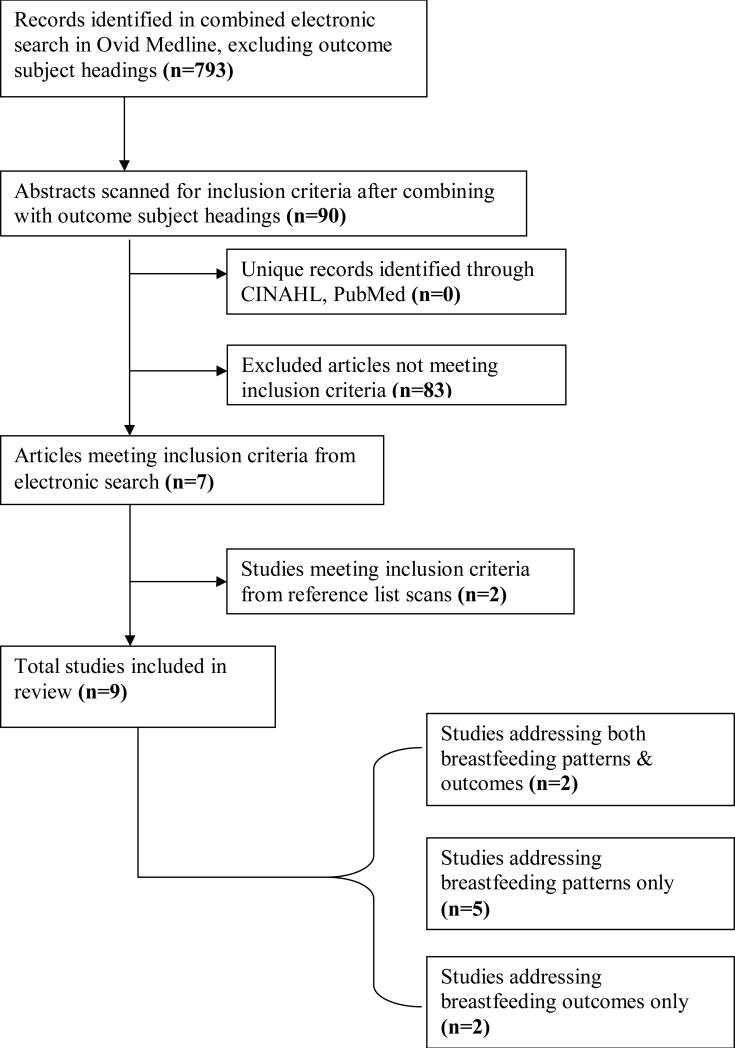

Within the electronic databases, the following indexed subject headings were searched: lactation, breastfeeding, premature birth, infant/premature, gestational age, morbidity, mortality, perinatal mortality, infant mortality, incidence, and prevalence. Late preterm, late prematurity and near term were searched as key words. Combined electronic searches using OvidMEDLINE without outcome subject headings (e.g., morbidity, mortality, etc.) yielded 793 citations. The search was narrowed by combining the initial search with each outcome subject heading, which yielded 90 results. These citations’ abstracts were scanned for sample and outcomes meeting inclusion criteria, and when present, the full-text article was retrieved for more detailed review. No unique, additional studies meeting inclusion criteria were identified through identical searching within other databases. Nine original research articles were included in the final review; two addressed both breastfeeding patterns and outcomes, two described only breastfeeding outcomes (i.e., morbidity), and five addressed only breastfeeding patterns (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search strategy and study selection.

Level of evidence was assessed according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2004). In this system, Level 1 represents the highest level of evidence (RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs), while Level 2 denotes cohort or case-control studies. Level 3 includes non-analytic studies (e.g., case reports), while Level 4 is expert opinion.

Results

Breastfeeding-Associated Re-Hospitalization, Morbidity, and Mortality within the Late Preterm Population

Of the four studies identified discussing breastfeeding outcomes, all were retrospective chart reviews, considered Level 2 evidence. Notably, no studies provided data on mortality. All were biased to some degree by the secondary nature of data sources and lack of quantification of breastfeeding. Tomashek et al. (2006) and Shapiro-Mendoza et al. (2006) both adjusted for factors known to affect breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., parity, prenatal care), while Bhutani and Johnson (2006) noted no significant between-group differences in baseline variables. Wang et al. (2004) did not control for potential group differences. Generalizations between studies are complicated by differing gestational age classifications, comparison groups, and outcomes of interest. As a group, however, these studies do seem to suggest that neonates born in the late preterm period who are breastfed at hospital discharge tend to fare worse than full-term breastfed infants or infants of similar gestation who are not breastfed.

In the first study, a population-based cohort study in Massachusetts involving 9,522 late preterm infants, breastfeeding at the birth hospitalization discharge emerged as the single greatest risk factor for the infant's re-hospitalization (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.33-2.04) (Shapiro-Mendoza et al., 2006). In another cohort study utilizing the same Massachusetts vital statistics database, the authors reported that among infants who breastfed at hospital discharge, late preterm infants were significantly more likely than term infants to be re-hospitalized (aRR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.5-3.2) and to receive hospital-related care after discharge (aRR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3-2.5). This difference was not observed between term and late preterm infants who were not breastfeeding at discharge (Tomashek et al., 2006). Wang and colleagues (2004) reported in their medical record review—a sample wherein roughly 80% of mothers initiated breastfeeding, that near-term infants (35 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation) were significantly more likely than term infants (≥ 37 weeks gestation) to experience a hospital discharge delay due to “poor feeding” (p = 0.029). Bhutani and Johnson (2006) found in their retrospective review of registry data that infants 35 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation (“nearly all breastfeeding”) were significantly more likely than infants ≥ 37 weeks to suffer from severe posticteric sequelae (p < 0.01). Table 1 summarizes the main outcomes of these studies.

Table 1.

Morbidity & Re-Hospitalizations among Late Preterm Breastfed Infants.

| Reference/Design | Study Purpose | Sample | Results/Effect Sizes Specific to Breastfeeding Morbidity | Limitations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tomashek et al. (2006) Retrospective chart review U.S. |

Evaluate differences in hospital readmissions & observational stays between FTIs and LPIs | 24,320 FTIs (≥ 37 wks gest.) and 1,004 LPIs (34-36 6/7 wks gest.) discharged < 2 days pp | Breastfed LPIs compared to breastfed FTIs: aRR 1.8 (1.2-2.6) for observational stay or hospital readmission aRR 2.2 (1.5-3.2) for hospital readmission aRR 1.3 (0.6-2.9) for observational stay |

Breastfeeding status defined only at time of birth certificate completion Unable to link all readmissions and birth records Secondary data sources Exclusion of multiples |

Individualized discharge instructions and close follow-up for breastfed LPIs Research to establish discharge & follow-up guidelines for breastfed LPIs |

|

Shapiro-Mendoza et al. (2006) Retrospective chart review U.S. |

Compare hospital readmissions and observational stays (i.e., morbidity) & mortality between healthy LPIs with/out risk factors | 9,552 “healthy” vaginally-delivered infants 34-36 6/7 wks gest. | Overall neonatal morbidity among breastfed LPIs, compared to non-breastfed LPIs: aRR 1.65 (1.33-2.04) * Mortality statistics not calculated due to low incidence |

Breastfeeding status defined only at time of birth certificate completion Unable to link 23% of rehospitalizations to birth records Secondary data sources Exclusion of multiples |

Closer hospital monitoring & follow-up of breastfed LPIs, especially with risk factors, including: Asian/Pacific Islander heritage, firstborn status, labor and delivery complications |

| NO EXCLUSIVE CATEGORY FOR INFANTS 34 0/7-36 6/7 WEEKS GESTATION | |||||

|

Wang et al. (2004) Retrospective chart review U.S. |

Test hypothesis that NTIs have more medical problems pp than FTIs | 120 NTIs (35-36 6/7 wks gestation) & 125 FTIs (≥ 37 wks gest.) ~80% breastfeeding rate |

Discharge delay due to “poor feeding:” NTIs: 75.9%; FTIs 28.6%: NTIs compared to FTIs, calculated OR 7.9 (1.2-49.9), p = 0.029 |

Gestational classification of NTI differs from LPI No objective identification of breastfeeding status or success at time of discharge Secondary data sources |

Ongoing breastfeeding assistance and support for NTIs Early supplementation with expressed breast milk or formula, if indicated Close observation for common NTI feeding complications; consider longer pp hospitalizations |

|

Bhutani & Johnson (2006) Retrospective review U.S. |

Comparison of etiology and clinical outcomes between LPIs and FTIs with a diagnosis of kernicterus or extreme hyperbilirubinemia | 96 FTIs (≥ 37 wks gest.) and 29 LPIs (35-36 6/7 wks gest.) part of Pilot Kernicterus Registry “Nearly all” LPIs breastfeeding |

Severe posticteric sequelae: LPIs: 82.7%; FTIs: 70.8% (p < 0.01) “Unsuccessful lactation experience” most common risk factor for hazardous hyperbilirubinemia in LPIs |

Sample not inclusive of full late preterm period No distinction among breastfed/non-breastfed LPI infants; breastfeeding in term infants not addressed “Unsuccessful lactation experience” not defined |

Assessment of pre-discharge hyperbilirubenemia risk; follow-up within 24-48 hrs for LPIs Family-centered care streamlined between hospital & pediatrician office Accurate, precise, universally available hyperbilirubinemia measures |

Key for Tables 1 & 2: Significant findings and non-U.S. study settings are bolded. Abbreviations: LPI= late preterm infant; NTI= near term infant; PTI= preterm infant; FTI= full-term infant; EBF= exclusively breastfed; PBF= partially breastfed; pp= postpartum; wks gest= weeks gestation; hrs= hours; aOR= adjusted odds ratio; parenthesized numbers indicate a 95% confidence interval

Other studies not meeting inclusion criteria for this review have noted higher rates of morbidity, including re-hospitalizations, due to “feeding problems” and jaundice among late preterm infants but have not delineated breastfeeding from formula feeding (Jain & Cheng, 2006; Lubow, How, Habli, Maxwell, & Sibai, 2009). Alternatively, some studies have found both late prematurity (or younger term gestations) and breastfeeding to be independently and significantly related to higher rates of hospital readmissions, but do not account for the interaction between breastfeeding and gestational age (Escobar et al., 2002; Maisels & Kring, 1998; Oddie, Hammal, Richmond, & Parker, 2005). Notably, Escobar and colleagues (2002) reported that within their large, retrospective case-control nested cohort study, the most prominent factors contributing to a re-hospitalization for dehydration among infants ≥ 36 weeks gestation included exclusive breastfeeding (AOR = 11.2, 95% CI: 3.9-32.6) and gestational age younger than 39 weeks (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.5-6.0).

Hall, Simon, and Smith (2000) did not include a separate category for late preterm infants in their retrospective medical record review of 125 breastfeeding infants, but similarly concluded that younger gestational age at or near term was a “significant risk factor [for hyperbilirubinemia and/or excessive weight loss/hypernatremia] leading to [hospital] readmission.” However, statistics to support this assertion were not included.

In contrast, a large population-based cohort study in Sweden found NICU-admitted moderately preterm infants (30 0/7-34 6/7 gestational weeks) who were breastfeeding at hospital discharge to have a hospitalization 2.7 days shorter than non-breastfed infants (p =.001) (Altman, Vanpe'e, Cnattingius, & Norman, 2009). However, because the infant population included in this analysis is younger and likely more acute than that observed in the other late preterm studies, comparisons may be imprudent.

Breastfeeding Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity within the Late Preterm Population

Seven studies were identified discussing breastfeeding patterns within the late preterm population. Three reported rates of breastfeeding initiation only, two discussed both breastfeeding initiation and duration, one accounted for both breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, and one reported breastfeeding exclusivity only. Major sources of bias present across these studies included secondary data sources, exclusion of multiple births, differing gestational age groupings, non-U.S. study settings, and small sample size and/or no reported effect size, all of which precluded broad generalizations among analyses. Study designs included retrospective chart reviews, cohort, and descriptive studies, and were thus considered Level 2 evidence of late preterm breastfeeding rates. The exception to this was the McKeever et al. (2002) study, which was a RCT. The level of evidence rating is non-applicable to this particular analysis, as the design of the study was intended to compare breastfeeding rates based on an intervention, not to examine breastfeeding rates within the general late preterm population.

As the individual study data indicate in Table 2, breastfeeding initiation rates among late preterm mother-infant dyads at around 59-70% are less than that of term infants and, possibly, younger preterm infants (Colaizy & Morriss, 2008; Donath & Amir, 2008; Merewood, Brooks, Bauchner, MacAuley, & Mehta, 2006; Shapiro-Mendoza et al., 2006; Tomashek et al., 2006). Although national breastfeeding rates for preterm infants as an exclusive group are not compiled, the late preterm breastfeeding initiation rate found here is less than the overall U.S. average as last reported by the CDC in 2004 at 73.1% ± 0.8 % (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009).

Table 2.

Initiation, Duration, & Exclusivity of Breastfeeding among Late Preterm Mother-Infant Dyads.

| Reference/Design | Study Purpose | Sample | Results/Effect Sizes Specific to Breastfeeding Patterns | Limitations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tomashek et al. (2006) See Table 1 |

See Table 1 | See Table 1 | Breastfeeding at hospital discharge: LPIs: 59.3% (n= 592) FTIs: 69.4% (n= 16,864) LPIs compared to FTIs, calculated OR 0.64 (0.56-0.73) |

See Table 1 | See Table 1 |

|

Shapiro-Mendoza et al. (2006) See Table 1 |

See Table 1 | See Table 1 | LPIs breastfeeding at hospital discharge: 70.0% (n = 6,651) |

See Table 1 | See Table 1 |

| NO EXCLUSIVE CATEGORY FOR INFANTS 34 0/7-36 6/7 WEEKS GESTATION | |||||

|

Merewood et al. (2006) Retrospective chart review U.S. |

Compare breastfeeding initiation rates among preterm and term infants | 67,884 singleton births between 24-42 wks gestation | Rates of breastfeeding initiation: 24-31 wks gest.: 62.9% 32-36 wks gest.: 70.1% 37-42 wks gest.: 76.8% “Older preterm” (32-36 6/7 wks gest.) as compared to FTI (37-42 wks gest.): aOR 0.73 (0.68-0.79) |

No exclusive LPI category Self-report of breastfeeding status via single, double-barreled question Some factors not controlled for (e.g., infant morbidity) Exclusion of multiples Secondary data sources |

Provision of additional knowledge, support, and equipment (e.g., breast pumps) for breastfeeding preterm dyads Research investigating breastfeeding practices or interventions for all gestational ages should consider maternal birthplace and race |

|

Colaizy & Morriss (2008) Retrospective review of survey data U.S. |

Test hypothesis that NICU admission reduces breastfeeding in U.S. infants | 29,940 NICU-admitted infants part of 2000-2003 PRAMS survey |

Infants 32-< 35 wks gest., NICU-admitted (n = 4949) vs. non-admitted (n = 467): Ever breastfed: 70.2% vs. 55.3% (p < 0.01) Breastfed > 4 wks pp: 49.1% vs. 35.1% (p < 0.01) Infants 35-< 38 wks gest. NICU-admitted (n = 8159) vs. non-admitted (n = 9601): Ever breastfed: 68.7% vs. 64% (p < 0.01) Breastfed > 4 wks pp: 47.6% vs. 43.5% (p < 0.01) Compared to infants ≥38 wks gest., breastfeeding > 4 wks pp: OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.78-0.97) infants 32-<35 wks gest. OR 0.78 (95% CI 0.73-0.83) infants 35-<38 wks gest. (lowest OR of any gestational cohort, including infants < 32 wks) |

No exclusive LPI category Self-report of all data |

Further research investigating factors within the NICU environment that are associated with successful breastfeeding initiation and continuation, especially among LPI (35-<38 wks gest.) |

|

Donath & Amir (2008) Population-based cohort study Australia |

Investigate effect of gestation on initiation and duration of breastfeeding | 3,600 singleton infants in Australia | NTI (35-36 6/7 wks gest.) breastfeeding rates & aOR's compared to infants ≥ 40 wks gest: Initiation: 88.2% aoR 0.64 (0.35-1.18) 6 months pp: 41.2% aOR 0.51 (0.34-0.76) *Lower rates for NTIs than for any other gestational age (e.g., ≤34 wks, ≥37 wks) |

No category inclusive of full late preterm period May not be representative of U.S. rates Exclusion of multiples Significance/effect size not reported for NTI compared to early PTI |

Individualized assessment and discharge planning for infants of 35-36 gestational weeks to improve chances of successful breastfeeding Need for awareness among clinicians that infants less than 40 weeks gestation (even 37-39 weeks) may be less likely to achieve successful breastfeeding |

|

Wooldridge & Hall (2003) Ex post facto descriptive correlational Canada |

Describe breastfeeding patterns of moderately preterm infants over 4 wks pp | 66 infants 30-35 6/7 wks gest. from 53 mothers in Canada | According to feeding diaries, rate of breastfeeding exclusivity: 1wk pp: 60.6% 4 wks pp: 59.1% Rate of exclusive & “primary” breastfeeds at breast increased steadily over 4 wks pp: 3% to 23% (exclusive); 18% to 27% (primary) Little variability in rates of breastfeeding exclusivity over 4 wks pp when breastfeeds not necessarily at breast |

No exclusive LPI category May not be representative of U.S. rates Small sample size, convenience sampling Possible rate inflation due to breastfeeding experience of research assistants 40% of sample was twins; non-comparable to other included studies Effect sizes/significance not reported |

Establishment of adequate milk supply before hospital discharge in moderately preterm mother-infant dyads More research examining breastfeeding patterns and best practices among moderately preterm twins; more clinical breastfeeding support for mothers of twins |

|

McKeever et al. (2002) Randomized controlled trial Canada |

Compare effects of breastfeeding support in hospital & home settings on breastfeeding outcomes and satisfaction in FTIs and NTIs | 75 FTIs (≥38 wks) and 37 NTIs (35-37 6/7 wks gest.) breastfeeding at hospital discharge | Breastfeeding exclusivity (past 24 hrs) at 5-12 days pp in standard care group: NTIs: 67.7% (n=12) FTIs: 73.5% (n=34) NTIs compared to FTIs, calculated OR 0.72 (0.17-2.98) |

No exclusive LPI category Very small sample of NTIs Short follow-up period Inclusion criteria requiring breastfeeding at discharge may inflate exclusivity rate May not be representative of U.S. rates |

Awareness that many NTIs require supplemental feeding after discharge, contributing to decreased breastfeeding exclusivity in this grp Research to determine optimal healthcare setting, frequency, and duration of support for breastfeeding mothers Healthcare policies to ensure availability of skilled, in-home lactation support for all breastfeeding mothers |

Breastfeeding duration statistics for late preterm infants are difficult to compile among studies due to wide variations in measurement periods (e.g., days, weeks, months), type of breastfeeding examined (e.g., exclusive versus any), regional differences (e.g., rates higher in some countries, such as Australia), and inconsistencies in gestational week classification categories (e.g., infants of 30 0/7-35 6/7 weeks often grouped as “moderately preterm”; “late preterm” or “near-term” may include gestational weeks 34-<40). However, as study data demonstrate in Table 2, with the exception of one study (Wooldridge & Hall, 2003), breastfeeding tends to decrease over the postpartum period within the late preterm population, and rates may even be less than that for either term or earlier preterm infants at several weeks postpartum (Colaizy & Morriss, 2008; Donath & Amir, 2008). Colaizy and Morriss (2008) suggest that their finding of higher breastfeeding rates among early preterm infants (< 32 weeks) may be a result of extra vigilance, breastfeeding support, and importance placed on breast milk feeds in the NICU, where younger preterm infants tend to outnumber late preterm infant admissions. As the incidence of late prematurity rises, breastfeeding rates within the late preterm population will likely become pivotal factors in reaching Healthy People 2010 goals of increasing breastfeeding to 75% initiation and 50% continuance at 6 months (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2000).

Only two reviewed studies (both conducted outside the U.S.) reported on breastfeeding exclusivity. Wooldridge and Hall (2003) found breastfeeding exclusivity among moderately preterm infants (30-35 6/7 weeks) to be approximately 60% during weeks one to four, while percentages of partial breastfeeding at these times were less than 15%. McKeever et al. (2002) reported breastfeeding exclusivity at 67.7% 5-12 days postpartum in a control group of 12 infants 35-37 6/7 weeks gestation breastfeeding at hospital discharge (see Table 2). Discrepancies and omissions in the reporting of breastfeeding exclusivity are problematic, as both the American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization recommend exclusive breastfeeding for six months postpartum.

Benefits of Breastfeeding among Infants Born Prematurely

Given the morbidity statistics, it may appear counterintuitive to recommend breastfeeding as the optimal infant feeding method and engage in efforts to increase breastfeeding rates among late preterm mother-infant dyads. Yet research suggests that the problem lies in the process (inadequate milk transfer), rather than product (breast milk). Indeed, preterm infants who lack the stamina to breastfeed but are supplemented with expressed breast milk tend to have better psychomotor, neurological, circulatory, and cognitive outcomes than those who are formula-fed (Lucas, Morley, Cole, & Gore, 1994; Rao, Hediger, Levine, Naficy, & Vik, 2002; Simeoni & Zetterstrom, 2005). Additionally, an extensive body of research has elucidated the many specific benefits of breast milk for preterm infants, which, with its complex and temporally-variant composition dependent upon post-conceptional age (Charpak, Ruiz, & Team, 2007) includes: enhanced gastrointestinal maturation; bolstered immunity demonstrated to decrease the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis, other infections, and allergies; and acceleration of myelinization, possibly leading to improved childhood cognitive function (Adams-Chapman, 2006; Callen & Pinelli, 2005; Engle & Kominiarek, 2008).

More generally, breastfeeding has been found to decrease the risk of later life obesity (Owen, Martin, Whincup, Smith, & Cook, 2005), and exclusive breastfeeding has been noted to save an estimated $200-475 on pediatrician office visits, hospitalizations, and prescriptions per infant during the first year of life, which is attributed to breast milk's immunologic protection against minor infant ills, including otitis media and respiratory tract infections (Ball & Wright, 1999; Hoey & Ware, 1997). Similarly, a very recent cost analysis projected a savings of $13 billion per year and prevention of over 911 deaths if the rate of breastfeeding exclusivity reached 90% in the U.S. (Bartick & Reinhold, 2010). One study suggests that the enhanced immunity noted in premature breastfed infants may be due, in part, to a greater total antioxidant capacity in premature breast milk, as compared to more mature breast milk or formula (Ezaki, Ito, Suzuki, & Tamura, 2008).

Breastfeeding itself may offer other advantages for preterm infants including positioning favorable for neuromotor development (Barradas, Fonseca, Guimaraes, & Lima, 2006; Dodd, 2005) and the fostering of mother-infant bonding and secure infant attachment, the latter two of which achieved at least partly through the reciprocity inherent in the act (Britton, Britton, & Gronwaldt, 2006; Callen & Pinelli, 2005; Dodd, 2005; Klaus & Kennel, 1976). Despite all of the documented advantages of breastfeeding among preterm infants, however, the extent of these benefits has not been systematically established for late preterm infants as a unique group.

Barriers to Breastfeeding in the Late Preterm Population

Infant-related barriers

Neither the trajectory nor the causes of poor breast milk intake among late preterm infants have been adequately addressed. Indeed, late prematurity in general has only recently been defined and studied in any depth. The literature suggests several physiologic issues, mainly developmental immaturities in the infant, which seem to contribute to suboptimal breastfeeding among late preterm infants. These include: cardiorespiratory instability contributing to rapid fatigue during feeding and subsequent inefficient breastfeeding; metabolic disturbances that necessitate supplementation; NICU admission and other medical conditions that separate mother and infant and limit the successful establishment of breastfeeding; immaturity of state regulation leading to overstimulation and fatigue during feeding; longer sleep intervals contributing to less overall time breastfeeding; uncoordinated suck, swallow, breathe organization; and, relative to term infants, decreased oro-motor tone which minimizes the negative pressure required for adequate milk flow (Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2008; Medoff-Cooper, McGrath, & Bilker, 2000; Medoff-Cooper & Ray, 1995; Wight, 2003).

These issues may concomitantly contribute to incomplete emptying of the breast, interfering with the supply-demand mechanism of breast milk production. Left unchecked, the phenomenon of insufficient milk supply ultimately ensues and infants who are exclusively, or mostly, breastfed may experience significant morbidities related to inadequate caloric intake. Unfortunately, this cascade of events typically transpires with the onset of lactogenesis II—copious milk production occurring two to three days post-birth (Meier, Furman, & Degenhardt, 2007), after the late preterm infant with no immediate health concerns has been discharged to home.

Mother-related barriers—preterm and term populations

While developmental immaturities of the infant likely play a significant role in late preterm breastfeeding difficulties, breastfeeding itself is a complex, reciprocal activity between the infant and mother. The maternal component of the issue has not yet been examined in depth, except to note that there may be difficulty in establishing breastfeeding due to maternal conditions causing or associated with the preterm birth. For example, type I diabetes, obesity, cesarean sections, and pregnancy-induced hypertension may delay lactogenesis II (Hartmann & Cregan, 2001; Rasmussen, Hilson, & Kjolhede, 2001; Sozmen, 1992; Wight, Morton, & Kim, 2008). Infections, multiple births, and medications used to treat some of these conditions (e.g., antibiotics, labor analgesia/anesthesia) may lead to postpartum separation of mother and infant, preventing early breastfeeding establishment (Wight, Morton, & Kim, 2008).

There are numerous studies generalized to premature and low-birthweight infants describing maternal perceptions of breastfeeding. These qualitative analyses describe feelings of disparity between breastfeeding expectations and reality (Sweet, 2008), objectification of breast milk (Sweet, 2006), concerns regarding inadequate milk volume and composition (Callen, Pinelli, Atkinson, & Saigal, 2005; Kavanaugh, Mead, Meier, & Mangurten, 1995), a duty versus reciprocal breastfeeding viewpoint (Flacking, Ewald, Nyqvist, & Starrin, 2006; Flacking, Ewald, & Starrin, 2007), and the act of breastfeeding as providing a claim on the infant and validating maternal identity (Kavanaugh, Meier, Zimmermann, & Mead, 1997). As a result of significant research in this area, evidence-based interventions for providing breastfeeding support in the neonatal intensive care unit have been delineated (Meier & Brown, 1996).

Maternal anxiety, stemming from an early or traumatic birth and/or the fragility of a preterm infant, has also been cited in the preterm literature as a contributor to breastfeeding failure. Specifically, anxiety has been implicated in the delay of lactogenesis II, though the pathophysiology of this process remains somewhat obscure (Chen, Nommsen-Rivers, Dewey, & Lonnerdal, 1998; Hartmann & Cregan, 2001; Neville & Morton, 2001). Some have postulated a negative effect of psychological stress on pulsatile oxytocin release, possibly modulated by opiate activity, which subsequently inhibits the milk ejection reflex and contributes to poor establishment of milk supply (Dewey, 2001; Lau, 2001; Ueda, Yokoyama, Irahara, & Aono, 1994). This process is supported by at least one randomized controlled trial involving 65 breastfeeding mothers of premature infants, which found that an audiotape of relaxation and visual imagery techniques listened to every other day for a week in resulted in 63% more milk yield in the treatment group compared to the control group, as measured in a single pumping one week later (Feher, Berger, Johnson, & Wilde, 1989).

Numerous studies of term infants have also demonstrated a negative association between anxiety and breastfeeding—revealing that the existence of postpartum anxiety independently accounts for breastfeeding non-initiation and early breastfeeding cessation (Britton, 2007; Papinczak & Turner, 2000; Ystrom, Niegel, Klepp, & Vollrath, 2008). In one study (Taveras et al., 2003), insufficient milk was the most frequently cited reason for early breastfeeding cessation, and lack of confidence in ability to breastfeed doubled the odds of breastfeeding discontinuation at 2 weeks postpartum (OR = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.02-7.6).

Other barriers to breastfeeding within the general population have been elucidated within the literature. These include competing work/school obligations, inadequate or conflicting breastfeeding information from health care providers, lack of breastfeeding support from significant others (Arora, McJunkin, Wehrer, & Kuhn, 2000), breastfeeding discomfort (Callen et al., 2005), and early use of pacifiers and breast milk supplementation (Dewey, Nommsen-Rivers, Heinig, & Cohen, 2003).

Current Guidelines

Despite the paucity of evidence, several publications exist that provide suggestions, guidelines, and frameworks for breastfeeding support among late preterm mother-infant dyads. These include the AWHONN Near-Term Infant Initiative, which describes a conceptual framework incorporating family role, care environment, nursing care, and infant physiologic-function status in optimizing the health of late preterm infants. Though specific recommendations are not proposed for breastfeeding management, the authors suggest the conceptual model as a useful framework providing guidance for future research (Medoff-Cooper, Bakewell-Sachs, Buus-Frank, Santa-Donato, & Near-Term Infant Advisory Panel, 2005).

Both Walker (2008) and Meier and colleagues (2007) describe the effects of common late preterm morbidities on breastfeeding and provide best practice suggestions for breast milk supplementation and maintenance of the maternal milk supply. Engle et al. (2007) propose specific criteria for discharge of late preterm infants who are breastfeeding, including 24 hours of successful feeding, formal evaluation of breastfeeding documented at least twice daily by trained caregivers, a feeding plan, and conduct of a risk assessment for development of severe hyperbilirubinemia. Wight (2003) additionally recommends a multidisciplinary discharge plan, including lactation consultation and pediatrician follow-up within 24-48 hours, and administrative considerations, including a written hospital breastfeeding policy, in caring for the breastfed late preterm infant. Smith, Donze, and Schuller (2007) suggest many of the same measures, but also recommend home visits by a lactation consultant until the infant reaches 40 weeks corrected age.

Perhaps the most comprehensive guidelines come from The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (2008), who recommends both inpatient and outpatient directives. These include a late preterm hospital breastfeeding order set and pathway, weight loss classifications warranting consideration for supplementation, formal lactation consultation within 24 hours of delivery, follow-up within 48 hours of hospital discharge, and weekly weight checks through 40 weeks corrected age. Though these protocols reflect best practice based on the state of the science of breastfeeding in the late premature period, most are based upon expert opinion and breastfeeding patterns in the general preterm population. See Table 3 for a summary of common guidelines.

Table 3.

Summary of Common Breastfeeding Recommendations for Late Preterm Infants.

| Recommendations | Clinical Review/Expert Opinion | Data-based Studies | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. (2007) | Walker (2008) | Wight (2003) | ABM (2008) | Engle et al. (2007) | Meier et al. (2007) | Bhutani & Johnson (2006) | Merewood et al. (2006) | McKeever et al. (2002) | Wang et al. (2004) | Tomashek et al. (2006) | Donath & Amir (2008) | Shapiro-Mendoza et al. (2006) | Wooldridge & Hall (2003) | Colaizy & Morriss (2008) | |

| Immediate STS care, 24-hr rooming-in | * | * | ** | ** | |||||||||||

| Football or cross-cradle positioning | * | * | |||||||||||||

| Pediatrician follow-up 24-28 hrs post-discharge, then frequently thereafter | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Hyperbilirubinemia risk assessment & monitoring | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Clinician/parental education & awareness re: increased lactation risk & normal LPI breastfeeding patterns | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Repeated, documented breastfeeding observations in-hospital | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Specific d/c criteria (e.g., established milk supply, 24 hrs successful feeding, etc.) | * | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Early use of interventions if not breastfeeding effectively (e.g., double electric pump, nipple shields, SNS) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| D/c feeding plan (written, individualized), evidence-based hospital pathway | * | * | ** | ** | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Close monitoring of output & weight pre/post-d/c (e.g., home test weights) | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Streamline care among HCPs pre/post-d/c | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Professional, experienced lactation support (e.g., lactation consultant) pre/post-d/c | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Further research re: optimal breastfeeding support, interventions, and discharge criteria | * | * | * | ||||||||||||

endorsement of 1st or only recommendation

endorsement of both 1st and 2nd recommendation

Abbreviations: STS= skin to skin; LPI= late preterm infant; D/C= discharge; SNS= supplemental nursing system; HCP= health care provider; ABM= The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine

Gaps in Knowledge and Future Research Directions

Infants born in the late premature period remain a largely understudied group. These infants appear to have poorer rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration compared to term (and possibly earlier preterm) infants, and those who are breastfed appear more vulnerable to significant morbidity. The scope and causes of substandard breastfeeding rates and outcomes among late preterm infants remain uncertain, however.

Discrepancies in definitions of breastfeeding and late prematurity, as well as differing breastfeeding measurement periods are problematic in quantifying breastfeeding rates and synthesizing the morbidity literature. In addition, the reviewed studies delineating breastfeeding morbidity rely on large retrospective chart reviews. In these analyses, the longest follow-up examining morbidity and mortality data is 28 days postpartum (with the exception of the Bhutani and Johnson study (2006)), and in all cases breastfeeding is vaguely defined as any breastfeeding at hospital discharge. Likewise, the majority of the late preterm literature reporting breastfeeding initiation and duration define breastfeeding in a dichotomous “any/none,” or occasionally “exclusive/any/none,” format, disregarding the dose-dependent effect of breastfeeding on infant health outcomes.

In order to create comparable outcomes and synthesize findings, future analyses of breastfeeding within the late preterm population should consider the following: 1) standard definitions of late prematurity as 34 0/7-36 6/7 weeks gestation; 2) consistency in reporting degrees of breastfeeding, such as those recommended by Labbok and Krasovec (1990) (e.g., exclusive, token, etc.); 3) clarification of breastfeeding status to include provision of expressed breast milk; 4) examination of breastfeeding and associated morbidity extended to 6-12 months postpartum, as the minimum time recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for breastfeeding exclusivity and continuation, respectively (Gartner et al., 2005); and 4) utilization of large, national datasets reporting breastfeeding rates with the potential to link these to infant health outcomes (particularly infant mortality, which is difficult to study owing to low incidence within individual studies).

Benefits of breast milk and breastfeeding in the late preterm population require empirical corroboration and comparison with advantages documented in term and earlier preterm populations. Though research clearly demonstrates an inverse relationship between gestational weeks and health benefits of breastfeeding, current analyses generally indicate increased risk inherent in exclusive breastfeeding among late preterm infants. As noted, this is likely due to breastfeeding process factors, rather than breast milk composition. Thus, there is a need for future analyses that consider breastfeeding benefits and morbidity/mortality within the late preterm population accounting for breastfeeding support, length of postpartum hospitalization, NICU admittance (which may confer additional breastfeeding support), and supplementation with expressed breast milk, as is standard practice in most NICUs and among early preterm infants.

Evidence suggesting that the current late preterm breastfeeding support is ineffective is provided by Escobar and colleagues (2005, 2006), who report an ostensibly protective effect of NICU admission on morbidity among breastfed late preterm infants—suggested to be due to the provision of additional guidance and breastfeeding support inherent in the NICU milieu. The finding is strengthened by Colaizy and Morriss (2008), who report higher breastfeeding rates among late preterm infants admitted to the NICU as compared to the well-baby nursery. Similarly, in the only randomized controlled trial found on breastfeeding interventions within the late preterm population, breastfeeding infants 35-37 6/7 weeks gestation who were discharged early and received home support from a certified lactation consultant had higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 5-12 days postpartum as compared to a control group receiving standard care (73.3% vs. 67.7%), though the sample was very small and results not statistically significant (McKeever et al., 2002).

Another gap in knowledge concerns the interplay of neonatal, maternal, social, and system factors contributing to late preterm breastfeeding failure. There is a need to more closely examine breastfeeding outcomes considering late preterm physiological maturity and health status, hospital routines and policy, timing and content of discharge and follow-up, the quality of the maternal-infant relationship, familial and cultural breastfeeding expectations, and other maternal physiological and psychological factors.

In particular, is unknown whether the same perceptions, anxieties, and resultant effects on breastfeeding observed among mothers of term and early preterm infants exist for mothers of late preterm infants. It may be hypothesized that maternal anxiety, thought to interfere with breast milk production, increases exponentially with the precariousness of the infant's medical condition and degree of prematurity. However, a recent prospective cohort study of 116 premature infants found that higher maternal perception of child vulnerability (as measured by the Vulnerable Child Scale) was predicted by maternal anxiety but not associated with neonatal illness severity factors, including gestational age, birthweight, or length of mechanical ventilation (Allen et al., 2004). Likewise, it is acknowledged that the mother-premature relationship is complex, in that mothers of medically-fragile infants may be more responsive to their infants than mothers of non-chronically ill premature infants (Holditch-Davis, Cox, Miles, & Belyea, 2003) and that increased stress related to caring for a premature infant is associated with more positive maternal involvement (Holditch-Davis, Schwartz, Black, & Scher, 2007).

Breastfeeding (and breast milk provision) evidence-based guidelines for late preterm mother-infant dyads are currently lacking. In order to develop sound policy and recommend specific institutional and discharge guidelines for breast milk feeds within this vulnerable group (e.g., pumping recommendations, follow-up care, indications for supplementation), additional research on breastfeeding outcomes in concordance with the above factors is imperative.

Implications for Practice

It is paramount that obsetric/neonatal nurses are aware of the increased risks to which breastfed late preterm infants are prone. Extra vigilance should be exercised in terms of monitoring and screening for hyperbilirubinemia and poor milk transfer. These observations should be documented regularly and systematically, in order that any departures from baseline may be recognized and treated rapidly. Additionally, it is the nurse's responsibility to advocate for appropriate care for the breastfeeding late preterm mother-infant dyad, including lactation consultation, no early discharges, and appropriately-tailored discharge instructions.

Hospital units might also consider forming committees or appointing staff responsible for policy development and review of current practices relative to the care of breastfed late preterm infants. It is vital that these parties regularly review current literature and institute a system for incorporating policy updates, as the evidence for best practice in this area is rapidly evolving.

Conclusions

The number of infants born in the late preterm period is increasing more rapidly than within any other gestational cohort. These infants have unique, often unrecognized, medical vulnerabilities that predispose them to high rates of morbidity and hospital readmissions. In particular, breastfeeding complications have emerged as a preeminent health concern for late preterm mother-infant dyads.

In order to improve breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates and infant health outcomes, clinicians must recognize and address the late preterm breastfeeding paradox. It is imperative that health care providers understand and communicate the overwhelming short- and long-term benefits of breast milk and breastfeeding as opposed to formula feeding among preterm infants, yet remain vigilant for evidence of poor breast milk transfer and infant problems related to poor intake. As current guidelines recommend and limited research suggests, mothers of late preterm infants should receive qualified, extended lactation support, frequent follow-up, and possibly delayed hospital discharges. In addition, supplementation with expressed breast milk will likely be necessary for a period of time.

Further research exploring causes of poor breastfeeding establishment and associated outcomes among late preterm mother-infant dyads is warranted. These preliminary analyses will be vital in informing subsequent randomized-controlled breastfeeding intervention trials and evidence-based guidelines.

Callout 1: Despite appearances comparable to their term counterparts, late preterm infants tend to lag behind in cardiorespiratory, metabolic, immunologic, neurologic, and motor development.

Callout 2: Breastfeeding at the birth hospitalization discharge emerged as the single greatest risk factor for the late preterm infant's re-hospitalization.

Callout 3: Physiological, psychological, process, and system factors affecting breastfeeding outcomes within the late preterm population warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgement

Funded by National Institute of Nursing Research grant 1F31NR011562.

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

References

- Adams-Chapman I. Neurodevelopmental outcome of the late preterm infant. Clinics in Perinatology. 2006;33(4):947–964. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen EC, Manuel JC, Legault C, Naughton MJ, Pivor C, O'Shea TM. Perception of child vulnerability among mothers of former premature infants. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):267–273. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman M, Vanpe'e M, Cnattingius S, Norman M. Moderately preterm infants and determinants of length of hospital stay. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2009;94:F414–F418. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.153668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, McJunkin C, Wehrer J, Kuhn P. Major factors influencing breastfeeding rates: Mother's perception of father's attitude and milk supply. Pediatrics. 2000;106(5):E67. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball TM, Wright AL. Health care costs of formula-feeding in the first year of life. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4 Pt 2):870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barradas J, Fonseca A, Guimaraes C, Lima G. Relationship between positioning of premature infants in Kangaroo Mother Care and early neuromotor development. Jornal de Pediatria. 2006;82(6):475–480. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartick M, Reinhold A. The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: A pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1048–1056. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani VK, Johnson L. Kernicterus in late preterm infants cared for as term healthy infants. Seminars in Perinatology. 2006;30(2):89–97. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JR. Postpartum anxiety and breast feeding. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2007;52(8):689–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JR, Britton HL, Gronwaldt V. Breastfeeding, sensitivity, and attachment. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1436–1443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callen J, Pinelli J. A review of the literature examining the benefits and challenges, incidence and duration, and barriers to breastfeeding in preterm infants. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2005;5(2):72–88. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callen J, Pinelli J, Atkinson S, Saigal S. Qualitative analysis of barriers to breastfeeding in very-low-birthweight infants in the hospital and postdischarge. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2005;5(2):93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Immunization Survey. [March 7, 2009];Breastfeeding among U.S. children born 1999-2005. 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.htm.

- Charpak N, Ruiz JG, Team KMC. Breast milk composition in a cohort of pre-term infants’ mothers followed in an ambulatory programme in Colombia. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96(12):1755–1759. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DC, Nommsen-Rivers L, Dewey KG, Lonnerdal B. Stress during labor and delivery and early lactation performance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;68(2):335–344. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaizy TT, Morriss FH. Positive effect of NICU admission on breastfeeding of preterm US infants in 2000 to 2003. Journal of Perinatology. 2008;28(7):505–510. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice ACOG committee opinion No. 404 April 2008. Late-preterm infants. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;111(4):1029–1032. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817327d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff MJ, Dias T, Damus K, Russell R, Bettegowda VR, Dolan S, et al. Changes in the gestational age distribution among U.S. singleton births: Impact on rates of late preterm birth, 1992 to 2002. Seminars in Perinatology. 2006;30(1):8–15. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG. Maternal and fetal stress are associated with impaired lactogenesis in humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(11):3012S–3015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3012S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):607–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd VL. Implications of kangaroo care for growth and development in preterm infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(2):218–232. doi: 10.1177/0884217505274698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath SM, Amir LH. Effect of gestation on initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal & Neonatal Edition. 2008;93(6):F448–450. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.133215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle WA, Kominiarek MA. Late preterm infants, early term infants, and timing of elective deliveries. Clinics in Perinatology. 2008;35(2):325–341. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle WA, Tomashek KM, Wallman C. “Late-preterm” infants: A population at risk. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1390–1401. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar GJ, Clark RH, Greene JD. Short-term outcomes of infants born at 35 and 36 weeks gestation: We need to ask more questions. Seminars in Perinatology. 2006;30(1):28–33. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar GJ, Gonzales VM, Armstrong M, Folck BF, Xiong B, Newman TB. Rehospitalization for neonatal dehydration: A nested case-control study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(2):155–161. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar GJ, Greene JD, Hulac P, Kincannon E, Bischoff K, Gardner MN, et al. Rehospitalisation after birth hospitalisation: Patterns among infants of all gestations. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(2):125–131. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.039974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki S, Ito T, Suzuki K, Tamura M. Association between total antioxidant capacity in breast milk and postnatal age in days in premature infants. Journal of Clinical and Biochemical Nutrition. 2008;42(2):133–137. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2008019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feher SD, Berger LR, Johnson JD, Wilde JB. Increasing breast milk production for premature infants with a relaxation/imagery audiotape. Pediatrics. 1989;83(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R, Ewald U, Nyqvist KH, Starrin B. Trustful bonds: A key to “becoming a mother” and to reciprocal breastfeeding. Stories of mothers of very preterm infants at a neonatal unit. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(1):70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R, Ewald U, Starrin B. “I wanted to do a good job”: Experiences of ‘becoming a mother’ and breastfeeding in mothers of very preterm infants after discharge from a neonatal unit. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(12):2405–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs K, Gyamfi C. The influence of obstetric practices on late prematurity. Clinics in Perinatology. 2008;35(2):343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner LM. Breastfeeding and jaundice. Journal of Perinatology. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S25–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210629. discussion S35-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, Naylor AJ, O'Hare D, Schanler RJ, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement- Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RT, Simon S, Smith MT. Readmission of breastfed infants in the first 2 weeks of life. Journal of Perinatology. 2000;20(7):432–437. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2007;56(7):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann P, Cregan M. Lactogenesis and the effects of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and prematurity. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(11):3016S–3020S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3016S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey C, Ware JL. Economic advantages of breast-feeding in an HMO: Setting a pilot study. American Journal of Managed Care. 1997;3(6):861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Cox MF, Miles MS, Belyea M. Mother-infant interactions of medically fragile infants and non-chronically ill premature infants. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26(4):300–311. doi: 10.1002/nur.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz T, Black B, Scher M. Correlates of mother-premature infant interactions. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(3):333–346. doi: 10.1002/nur.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Cheng J. Emergency department visits and rehospitalizations in late preterm infants. Clinics in Perinatology. 2006;33(4):935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh K, Mead L, Meier P, Mangurten HH. Getting enough: Mothers’ concerns about breastfeeding a preterm infant after discharge. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 1995;24(1):23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1995.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh K, Meier P, Zimmermann B, Mead L. The rewards outweigh the efforts: Breastfeeding outcomes for mothers of preterm infants. Journal of Human Lactation. 1997;13(1):15–21. doi: 10.1177/089033449701300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khashu M, Narayanan M, Bhargava S, Osiovich H. Perinatal outcomes associated with preterm birth at 33 to 36 weeks’ gestation: A population-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):109–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus MH, Kennel JH. Maternal-infant bonding. The C.V. Mosby Company; St. Louis, MO: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauve R, Liston R. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. JAMA. 2000;284(7):843–849. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbok M, Krasovek K. Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Studies in Family Planning. 1990;21(4):226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. Effects of stress on lactation. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2001;48(1):221–234. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubow JM, How HY, Habli M, Maxwell R, Sibai BM. Indications for delivery and short-term neonatal outcomes in late preterm as compared with term births. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;200(5):e30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ, Gore SM. A randomised multicentre study of human milk versus formula and later development in preterm infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal & Neonatal Edition. 1994;70(2):F141–146. doi: 10.1136/fn.70.2.f141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisels MJ, Kring E. Length of stay, jaundice, and hospital readmission. Pediatrics. 1998;101(6):995–998. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, et al. Births: Final data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2007;56(6):1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever P, Stevens B, Miller K, MacDonell JW, Gibbins S, Guerriere D, et al. Home versus hospital breastfeeding support for newborns: A randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2002;29(4):258–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoff-Cooper B, Bakewell-Sachs F, Buus-Frank ME, Santa-Donato A, Near-Term Infant Advisory Panel The AWHONN Near-Term Infant Initiative: A conceptual framework for optimizing health for near-term infants. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(6):666–671. doi: 10.1177/0884217505281873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Bilker W. Nutritive sucking and neurobehavioral development in preterm infants from 34 weeks PCA to term. MCN, American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2000;25(2):64–70. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoff-Cooper B, Ray W. Neonatal sucking behaviors. Image - the Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1995;27(3):195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1995.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier PP, Brown LP. State of the science. Breastfeeding for mothers and low birth weight infants. Nursing Clinics of North America. 1996;31(2):351–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier PP, Furman LM, Degenhardt M. Increased lactation risk for late preterm infants and mothers: Evidence and management strategies to protect breastfeeding. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 2007;52(6):579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merewood A, Brooks D, Bauchner H, MacAuley L, Mehta SD. Maternal birthplace and breastfeeding initiation among term and preterm infants: A statewide assessment for Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1048–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville MC, Morton J. Physiology and endocrine changes underlying human lactogenesis II. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(11):3005S–3008S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3005S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddie SJ, Hammal D, Richmond S, Parker L. Early discharge and readmission to hospital in the first month of life in the Northern Region of the UK during 1998: A case cohort study. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(2):119–124. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: A quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1367–1377. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papinczak TA, Turner CT. An analysis of personal and social factors influencing initiation and duration of breastfeeding in a large Queensland maternity hospital. Breastfeeding Review. 2000;8(1):25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju TNK. Epidemiology of late preterm (near-term) births. Clinics in Perinatology. 2006;33(4):751–763. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju TNK, Higgins RD, Stark AR, Leveno KJ. Optimizing care and outcome for late-preterm (near-term) infants: A summary of the workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1207–1214. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen KM, Hilson JA, Kjolhede CL. Obesity may impair lactogenesis II. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(11):3009S–11S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3009S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MR, Hediger ML, Levine RJ, Naficy AB, Vik T. Effect of breastfeeding on cognitive development of infants born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91(3):267–274. doi: 10.1080/08035250252833905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RB, Green NS, Steiner CA, Meikle S, Howse JL, Poschman K, et al. Cost of hospitalization for preterm and low birth weight infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e1–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [August 9, 2010];SIGN: A guideline developers’ handbook. Section 6: Forming guideline recommendations. 2004 from http://cys.bvsalud.org/lildbi/docsonline/4/6/164-sign50section6.pdf.

- Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tomashek KM, Kotelchuck M, Barfield W, Weiss J, Evans S. Risk factors for neonatal morbidity and mortality among “healthy,” late preterm newborns. Seminars in Perinatology. 2006;30(2):54–60. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni U, Zetterstrom R. Long-term circulatory and renal consequences of intrauterine growth restriction. Acta Paediatrica. 2005;94(7):819–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, Donze A, Schuller L. An evidence-based review of hyperbilirubinemia in the late preterm infant, with implications for practice: Management, follow-up, and breastfeeding support. Neonatal Network. 2007;26(6):395–405. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.26.6.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozmen M. Effects of early suckling of cesarean-born babies on lactation. Biology of the Neonate. 1992;62(1):67–68. doi: 10.1159/000243855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet L. Breastfeeding a preterm infant and the objectification of breastmilk. Breastfeeding Review. 2006;14(1):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet L. Birth of a very low birth weight preterm infant and the intention to breastfeed ‘naturally’. Women & Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2008;21(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras EM, Capra AM, Braveman PA, Jensvold NG, Escobar GJ, Lieu TA. Clinician support and psychosocial risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1):108–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine [March 3, 2010];Protocol #10: Breastfeeding the near-term infant (35 to 37 weeks gestation) 2008 from http://www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx.

- The Consortium on Safe Labor Respiratory morbidity in late preterm births. JAMA. 2010;304(4):419–425. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomashek KM, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Weiss J, Kotelchuck M, Barfield W, Evans S, et al. Early discharge among late preterm and term newborns and risk of neonatal morbidity. Seminars in Perinatology. 2006;30(2):61–68. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T, Yokoyama Y, Irahara M, Aono T. Influence of psychological stress on suckling-induced pulsatile oxytocin release. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1994;84(2):259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [July 28, 2007];Healthy People 2010. Maternal, infant, and child health: 16-19. (2nd ed.). 2000 2 from http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/HTML/Volume2/16MICH.htm. [PubMed]

- Walker M. Breastfeeding the late preterm infant. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37(6):692–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Dorer DJ, Fleming MP, Catlin EA. Clinical outcomes of near-term infants. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):372–376. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight NE. Breastfeeding the borderline (near-term) preterm infant. Pediatric Annals. 2003;32(5):329–336. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20030501-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight NE, Morton JA, Kim JH. Best medicine: Human milk in the NICU. Hale Publishing; Amarillo, TX: 2008. Breastfeeding the late preterm infant. pp. 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J, Hall WA. Posthospitalization breastfeeding patterns of moderately preterm infants. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2003;17(1):50–64. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ystrom E, Niegel S, Klepp K-I, Vollrath ME. The impact of maternal negative affectivity and general self-efficacy on breastfeeding: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]