The variable portion of the γ-protocadherin (Pcdh-γ) cytoplasmic domain (VCD) controls Pcdh-γ trafficking and organelle tubulation in the endolysosome system. Active VCD segments are conserved in Pcdh-γA and Pcdh-γB subfamilies.

Abstract

Clustered protocadherins (Pcdhs) are arranged in gene clusters (α, β, and γ) with variable and constant exons. Variable exons encode cadherin and transmembrane domains and ∼90 cytoplasmic residues. The 14 Pcdh-αs and 22 Pcdh-γs are spliced to constant exons, which, for Pcdh-γs, encode ∼120 residues of an identical cytoplasmic moiety. Pcdh-γs participate in cell–cell interactions but are prominently intracellular in vivo, and mice with disrupted Pcdh-γ genes exhibit increased neuronal cell death, suggesting nonconventional roles. Most attention in terms of Pcdh-γ intracellular interactions has focused on the constant domain. We show that the variable cytoplasmic domain (VCD) is required for trafficking and organelle tubulation in the endolysosome system. Deletion of the constant cytoplasmic domain preserved the late endosomal/lysosomal trafficking and organelle tubulation observed for the intact molecule, whereas deletion or excision of the VCD or replacement of the Pcdh-γA3 cytoplasmic domain with that from Pcdh-α1 or N-cadherin dramatically altered trafficking. Truncations or internal deletions within the VCD defined a 26–amino acid segment required for trafficking and tubulation in the endolysosomal pathway. This active VCD segment contains residues that are conserved in Pcdh-γA and Pcdh-γB subfamilies. Thus the VCDs of Pcdh-γs mediate interactions critical for Pcdh-γ trafficking.

INTRODUCTION

Clustered protocadherins (Pcdhs) are the largest subgroup from the cadherin family of transmembrane proteins that mediate homophilic cell–cell adhesion. Pcdh genes are arranged in three gene clusters (α, β, and γ) that contain 14, 22, and 22 distinct protocadherin genes, respectively, in rodents (Kohmura et al., 1998; Wu and Maniatis, 1999). For the α and γ clusters, the mRNAs are spliced (Tasic et al., 2002) to three exons that code for a common cytoplasmic domain of 152 or 124 amino acids, respectively, appended to each molecule. It is believed that Pcdhs therefore couple homophilic recognition to common cytoplasmic interactions in synapse formation and development of the nervous system. For this reason, most attention has focused on the Pcdh-α and Pcdh-γ constant domains in terms of determining how Pcdhs interact with cytoplasmic proteins (Kohmura et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010).

Some Pcdhs, including the Pcdh-γs, have been shown to participate in homophilic cell–cell interactions (Obata et al., 1995; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). However, knockout phenotypes suggest the molecules could have nonconventional roles during neural development. For example, total knockout of the Pcdh-γ gene cluster primarily caused cell death in the spinal cord and other regions of the CNS (Wang et al., 2002; Weiner et al., 2005). Conditional knockouts of Pcdh-γs in spinal cord (Prasad et al., 2008) or retina (Lefebvre et al., 2008) have confirmed that cell death is a prominent phenotype. Prevention of apoptosis in Pcdh-γ knockouts by Bax double knockout revealed reductions in synapse connectivity for spinal cord (Weiner et al., 2005) but no defects in synaptic connectivity in the retina (Lefebvre et al., 2008). In contrast to these phenotypes observed upon knockout of Pcdh-γ, disruption of Pcdh-αs had deficiencies in serotonergic and olfactory projections with no cell death (Katori et al., 2009).

We showed previously that endogenous Pcdh-γs (Phillips et al., 2003; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2010), as well as those that are overexpressed (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009, 2010; Hanson et al., 2010a), are mostly intracellular and suggested that this property could account for the relatively weak cellular adhesion observed for Pcdh-γs (Obata et al., 1995). Pcdh-γs induce tubulation of organelles in the late endosome/lysosome system (Hanson et al., 2010a). It is possible that the intracellular distribution and organelle tubulation activity of Pcdh-γs reflect a role for these molecules in an unusual intracellular trafficking route critical for neural development and survival. We sought to determine how the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domains influence trafficking, using Pcdh-γA3 as the model. We found that the Pcdh-γA3 and Pcdh-γB2 variable cytoplasmic domains (VCDs) participate in trafficking of the intact molecules. Truncations or internal deletions of the Pcdh-γA3 VCD revealed a 26–amino acid segment that is required for late endosome tubulation and targeting. This segment has conserved residues in Pcdh-γA and Pcdh-γB families. Our results suggest the Pcdh-γ VCD mediates interactions critical for Pcdh-γ trafficking and function.

RESULTS

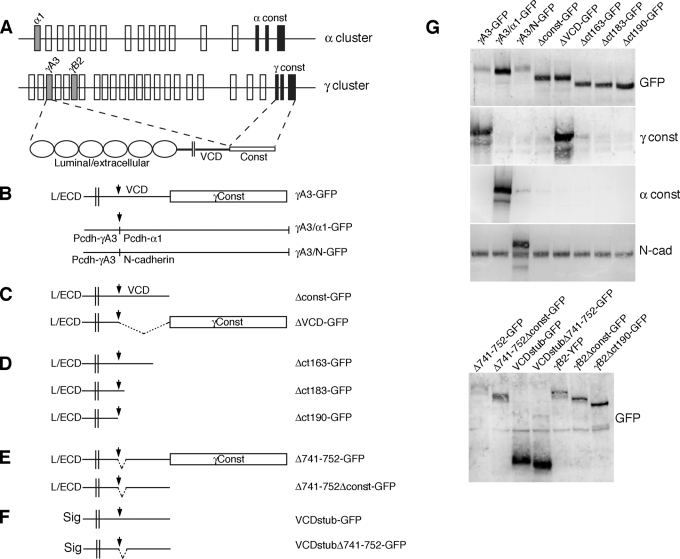

Pcdh-γ green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions are functional in vivo: GFP knock-in fusions do not cause the cell death phenotype observed upon disruption of the Pcdh-γ gene cluster (Wang et al., 2002; Weiner et al., 2005; Lefebvre et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2008; Han et al., 2010; Su et al., 2010). Pcdh-γA3–GFP expressed in HEK293 cells was targeted to LAMP-2–positive organelles representing late endosomes or lysosomes, and this activity depended on an intact cytoplasmic domain (Hanson et al., 2010a). To determine whether the cytoplasmic domains from related proteins, such as a member of the Pcdh-α family (Figure 1A) or the more distantly related classical cadherin N-cadherin, can substitute for the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain in promoting correct trafficking of Pcdh-γs, we generated chimeric molecules in which most of the Pcdh-γA3 cytoplasmic domain was replaced with that from Pcdh-α family member Pcdh-α1 (γA3/α1-GFP) or, the classic cadherin, N-cadherin (γA3-N-GFP; Figure 1B). We also generated Pcdh-γA3 constructs in which the constant domain (Δconst-GFP) or the VCD (ΔVCD-GFP; Figure 1C) was deleted, as well as carboxy-terminal truncations of the intact molecule that terminated at different sites within the VCD (Δct163-GFP, Δct183-GFP, and Δct190-GFP; Figure 1D). Twelve–amino acid internal deletions within the Pcdh-γA3 VCD were generated within the context of full-length or constant-domain-deleted Pcdh-γA3 (Δ741-752-GFP and Δ741-752Δconst-GFP, respectively; Figure 1E). A VCD stub construct was generated in which the entire luminal/extracellular domain was replaced with a signal sequence and the constant domain deleted as well (VCDstub-GFP; Figure 1F). The 12–amino acid VCD deletion was also introduced into the VCD stub construct (VCDstubΔ741-752; Figure 1F). All of the constructs were expressed and reacted with the appropriate antibodies (Figure 1G).

FIGURE 1:

Recombinant Pcdh-γA3-GFP molecules to map intracellular trafficking motifs. (A) Pcdh-α and Pcdh-γ gene clusters. Exons for the representative Pcdh-γ and Pcdh-α molecules are shaded. An example of Pcdh-γA3 splicing to Pcdh-γ constant exons, yielding the full-length gene product, is shown. (B) The location of the XbaI site, used to join cytoplasmic domains from other molecules, or to create deletions and truncations, is indicated (arrow) relative to the luminal/extracellular (L/ECD), transmembrane (double lines) variable cytoplasmic (VCD), and constant domains (Const). Outline of chimeric constructs in which the cytoplasmic domain of Pcdh-α1 (γA3/α1-GFP) or N-cadherin (γA3/N-GFP) was substituted for the native Pcdh-γA3 cytoplasmic domain. (C) Deletion constructs in which the entire constant domain (Δconst-GFP) was deleted or where the VCD (ΔVCD-GFP) was excised. (D) Carboxy-terminal truncation constructs in which portions of the VCD were successively truncated. (E) Constructs in which 12 amino acids (amino acids 741–752 as numbered in full-length mouse Pcdh-γA3) were excised from the VCD within the context of the full-length molecule (Δ741-752-GFP; top) or constant-domain-deleted version (Δ741-752-GFPΔconst; bottom). (F) Constructs that contain only a small extracellular segment, including a signal sequence (Haas et al., 2005), followed by the transmembrane segment and the VCD with no constant domain (VCDstub-GFP; top), including the 12–amino acid VCD deleted version (VCDstubΔ741-752; bottom). (G) All constructs were expressed at the correct molecular weight and reacted with appropriate antibodies by Western blot.

Late endosome/lysosome targeting and tubulation are specific to the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain

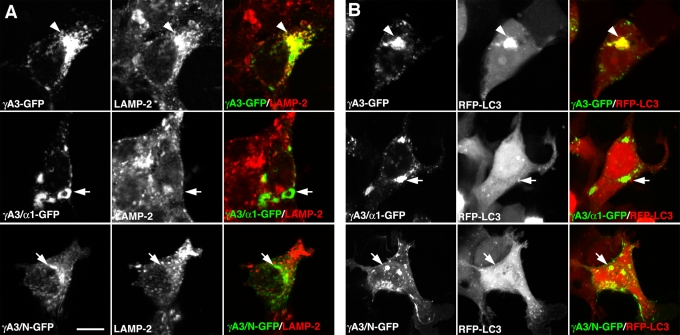

To determine the specificity of targeting mediated by the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain, we transfected the chimeric γA3/α1-GFP and γA3/N-GFP constructs, as well as intact γA3-GFP, and examined their targeting to the endolysosome system by immunostaining with antibodies to the lysosomal marker LAMP-2 or coexpressed the chimeras with red fluorescent protein (RFP)–MAP1A/1B light chain 3 (LC3), the autophagic protein that was found to participate in Pcdh-γ membrane tubulation (Hanson et al., 2010a). Although γA3-GFP (Figure 2A, top) generated perinuclear accumulations that colocalized with LAMP-2 (arrowheads), intracellular accumulations of γA3/α1-GFP or γA3/N-GFP (Figure 2A, middle and bottom) lacked specific LAMP-2 colocalization (arrows). γA3-GFP (Figure 2B, top) also induced the perinuclear clustering of RFP-LC3 (arrowheads), whereas intracellular clusters of γA3/α1-GFP or γA3/N-GFP (Figure 2B, middle and bottom) never coclustered with RFP-LC3 (arrows).

FIGURE 2:

Specific targeting to LAMP-2– and LC3-positive organelles by the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain. γA3-GFP colocalized with and recruited LAMP-2–positive (A) and RFP-LC3–positive (B) organelles in a perinuclear distribution (A and B, arrowheads). In contrast, intracellular accumulations of the γA3/α1–GFP chimera or the γA3/N–GFP chimera never specifically colocalized with or recruited LAMP-2–positive (A) or RFP-LC3–positive (B) organelles (A and B, arrows). Bar, 10 μm.

We compared the intracellular distribution and morphology of organelles associated with the chimeras using correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM; Hanson et al., 2010b). In cells, γA3-GFP (Figure 3A) was associated with intracellular tubules (Figure 3A, arrowheads) and ∼170-nm multivesicular organelles (Figure 3A, arrows). Removal of most of the cytoplasmic domain (Δct190-GFP) caused the molecule to be more efficiently transported to cell–cell contacts (not shown here; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010) and also eliminated the tubules and multivesicular organelles when found intracellularly, resulting in membrane whorls (Figure 3B), as observed previously (Hanson et al., 2010a). These whorls also colocalized with endoplasmic reticulum markers (not shown here; Hanson et al., 2010a). In contrast, replacement of the Pcdh-γA3 cytoplasmic domain with that from Pcdh-α1 (γA3/α1-GFP; Figure 3C) or N-cadherin (γA3/N-GFP; Figure 3D) resulted in strikingly different organelles. For γA3/α1-GFP, the molecule accumulated in organelles associated with apparent ribosomes (Figure 3, C and E, arrowheads), similar to those previously observed when intact Pcdh-α1–GFP was expressed (Hanson et al., 2010a). When γA3/N-GFP was expressed, there was a strong tendency for the chimera to target to cell–cell junctions (Figure 3D, inset). However, when found, intracellular accumulations of γA3/N-GFP (Figure 3D) resembled the whorls associated with Δct190-GFP (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3:

Organelle tubulation in the endolysosome pathway requires the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain. (A) γA3-GFP intracellular expression corresponded to tubules (arrowheads) and ∼170-nm multivesicular organelles (arrow). (B) Deletion of most of the cytoplasmic domain, including the entire constant domain and most of the VCD (Δct190-GFP) eliminated the tubules and resulted in the formation of membrane whorls when found intracellularly as previously observed (Hanson et al., 2010a). Inset, a “figure-8” whorl seen in both confocal and EM images. (C) In contrast, γA3/α1-GFP accumulated in organelles that were associated with ribosomes (E, arrowhead). (D) γA3/N-GFP, although mostly localized at cell–cell contacts (inset), when found intracellularly, was associated with membrane whorls similar to those observed upon expression of Δct190-GFP. Bar, 500 nm in EM images and 5 μm in light images in A–D and 70 nm in E.

Late endosome/lysosome trafficking and tubulation are mediated by the Pcdh-γ VCD

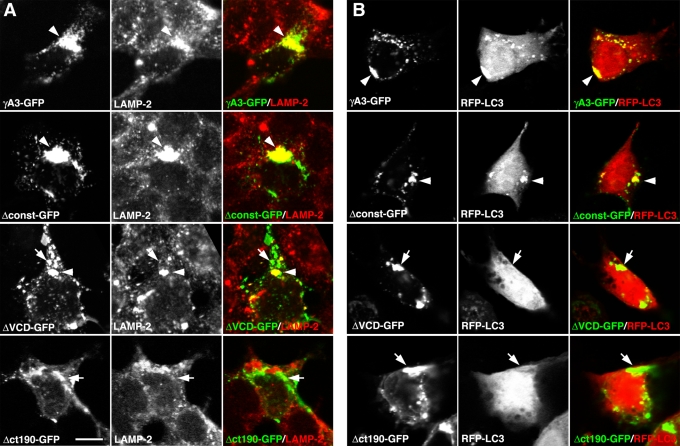

To map the region(s) within the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain that mediate trafficking and tubulation in the late endosome/lysosome system, the Pcdh-γA3 constant domain (Δconst-GFP) or the VCD (ΔVCD-GFP) was deleted (Figure 1). Unlike Δct190-GFP, Δconst-GFP, and ΔVCD-GFP, as well as γA3-GFP (Figure 4A), all colocalized to some extent with LAMP-2 (arrowheads), although γA3-GFP and Δconst-GFP exhibited a perinuclear pattern, whereas ΔVCD-GFP had more dispersed intracellular localization, with some of the ΔVCD-GFP puncta not colocalizing with LAMP-2 (Figure 4A, arrows). Both γA3-GFP and Δconst-GFP colocalized with and induced the clustering of RFP-LC3 (Figure 4B, arrowheads). Of interest, no colocalization and clustering of RFP-LC3 were observed with ΔVCD-GFP, with RFP-LC3 remaining diffuse in these cells, similar to the lack of RFP-LC3 colocalization exhibited by Δct190-GFP (Figure 4B, arrows). Thus, although both the VCD and the constant domain appear to have separate intracellular retention signals, the VCD contains sequences necessary for efficient transport to the late endosome/lysosome pathway and LC3 recruitment.

FIGURE 4:

The Pcdh-γA3 VCD is required for trafficking to LAMP-2– and RFP-LC3–positive organelles. Deletion of the constant domain (Δconst-GFP) did not affect the trafficking of the resultant molecule to LAMP-2–positive (A) and RFP-LC3-positive (B) organelles in a perinuclear manner, similar to that observed for full-length γA3-GFP (A and B, arrowheads). In contrast, excision of the VCD (ΔVCD-GFP), although still resulting in an intracellular distribution, exhibited accumulations that largely did not colocalize with LAMP-2 (A, arrows) and never with RFP-LC3 (B, arrows). A fraction of ΔVCD-GFP accumulations did colocalize with LAMP-2 (A, arrowheads). Large-scale perinuclear recruitment of ΔVCD-GFP was not observed. By comparison, Δct190-GFP did not colocalize with LAMP-2 or RFP-LC3 (A and B, arrows), consistent with previous observations. Bar, 10 μm.

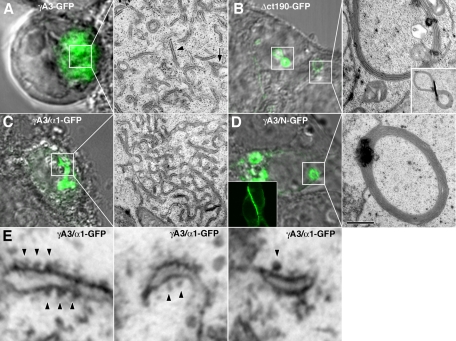

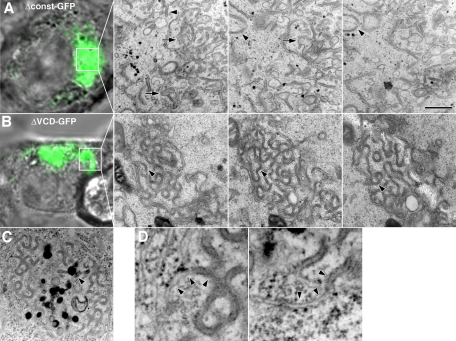

We used CLEM and serial sectioning to compare the organelles associated with Δconst-GFP and ΔVCD-GFP. We found that Δconst-GFP expression corresponded to tubules (Figure 5A, arrowheads) and ∼170-nm vesicles (Figure 5A, arrows) that were similar to those found in intact γA3-GFP–expressing cells (Figure 3; Hanson et al., 2010a). In contrast, ΔVCD-GFP fluorescence corresponded to sinusoidal membrane sheets that strongly resembled “cubic” membranes described previously (Lingwood et al., 2009). Unlike tubules, these sheets exhibited continuity from section to section (Figure 5B, arrowheads). ΔVCD-GFP was also associated with electron-dense, lysosome-like organelles (Figure 5C, arrowheads), suggesting the possibility of a separate lysosome targeting sequence in the constant domain. High magnification of ΔVCD-GFP–associated organelles showed continuity with endoplasmic reticulum (ER; Figure 5D, arrowheads). Overall, these observations indicate that the VCD can account for most of the normal trafficking activity observed for the intact molecule, although the constant domain can also mediate some aspect of intracellular retention.

FIGURE 5:

The Pcdh-γA3 VCD is required for tubulation in the endolysosome system. Serial section CLEM reveals that (A) Δconst-GFP expression was associated with tubules (arrowheads) and ∼170-nm organelles (arrows) similar to those observed upon expression of the full-length molecule (Figure 3A). In contrast, (B) ΔVCD-GFP expression was associated with sinusoidal membrane sheet accumulations, similar to those observed previously (Lingwood et al., 2009). (C) ΔVCD-GFP membranes were associated with electron-dense lysosomes (arrowheads), which could account for the partial LAMP-2 colocalization observed for this construct. Bar, 500 nm in EM images and 5 μm in light images in A–C and 70 nm in D.

Organelle targeting and tubulation are mediated by a 26–amino acid segment within the VCD

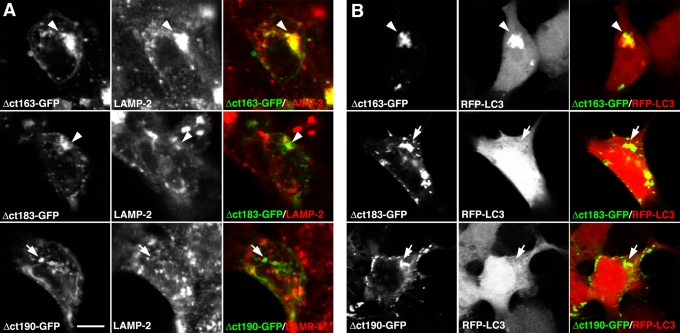

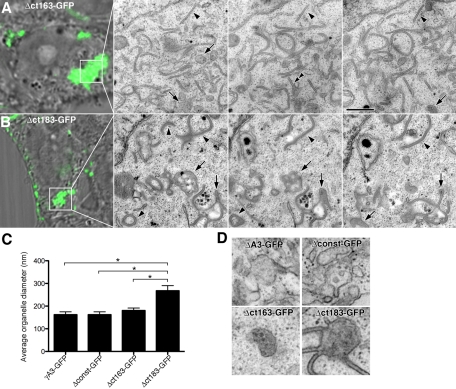

To further characterize the residues within the VCD that dictate Pcdh-γ trafficking, we generated additional truncated versions of Pcdh-γA3 in which the molecule was C-terminally truncated at two different sites within the VCD (Δct163-GFP and Δct183-GFP; Figure 1) and tested these for LAMP-2 colocalization, LC3 recruitment, and tubulation activity. Δct163-GFP exhibited colocalization with LAMP-2 organelles in a perinuclear manner (Figure 6A, top, arrowheads) similar to full-length γA3-GFP and Δconst-GFP (Figures 2 and 4). Unlike Δct163-GFP, however, Δct183-GFP puncta lacked extensive clustering at perinuclear sites and had only a partial colocalization with LAMP-2 (Figure 6A, middle, arrowheads). Δct183-GFP/LAMP-2 colocalization was still more prominent than that of Δct190-GFP, which never specifically colocalized with LAMP-2 (Figure 6, bottom). Δct163-GFP also recruited RFP-LC3 (Figure 6B, top, arrowheads), whereas both Δct183-GFP and Δct190-GFP did not (Figure 6B, middle and bottom, arrows). By serial section CLEM, Δct163-GFP corresponded to tubules and multivesicular organelles that were indistinguishable from those found upon Δconst-GFP or full-length γA3-GFP expression (Figure 7, A, C, and D). In contrast, the organelles associated with Δct183-GFP were substantially different. In this case Δct183-GFP was associated with larger organelles, ∼250 nm in diameter, with associated tubular structures (Figure 7, B–D). Serial sectioning through Δct183-GFP–associated organelles revealed that the tubules were invariably attached to the larger vesicles (Figure 7, B and D). Comparison of the size of the multivesicular organelles corresponding to expression of γA3-GFP, Δconst-GFP, Δct163-GFP, and Δct183-GFP indicates that Δct183-GFP–associated organelles were significantly larger than those of γA3-GFP, Δconst-GFP, and Δct163-GFP, which were statistically the same (Figure 7C).

FIGURE 6:

Effect of proximal and distal VCD truncations on LAMP-2 colocalization and RFP-LC3 recruitment. Δct163-GFP (A) colocalized with LAMP-2–positive organelles and (B) recruited RFP-LC3 (A and B, arrowheads), similar to Δconst-GFP and full-length γA3-GFP. In contrast, Δct183-GFP partially colocalized with LAMP-2 organelles (A, arrowheads) and lacked RFP-LC3 recruitment activity (B, arrows). Removal of an additional six amino acids (Δct190-GFP) completely eliminated LAMP-2 colocalization, as well as RFP-LC3 recruitment (arrowheads). Bar, 10 μm.

FIGURE 7:

Serial sectioning CLEM reveals differences in Pcdh-γA3 proximal and distal VCD truncations. Serial sections through cells transfected with (A) Δct163-GFP or (B) Δct183-GFP. (A) Δct163-GFP was associated with ∼170-nm organelles (A, arrows) and tubules (arrowheads), similar to Δconst-GFP and full-length γA3-GFP. By contrast, Δct183-GFP (B) was associated with a different organelle profile. Apparent tubules (B, arrowheads) remain attached to large multivesicular organelles approximately ∼250 nm in diameter. (C) Diameter of multivesicular organelles associated with the indicated constructs. γA3-GFP–, Δconst-GFP–, and Δct163-GFP–associated organelles were statistically indistinguishable (t test, p > 0.2) but all were different from the organelles found associated with Δct183-GFP (t test, p < 0.002). (D) Examples of multivesicular organelles associated with the indicated constructs. Bar, 500 nm in EM images in A and B, 5 μm in light images in A and B, and 250 nm in D.

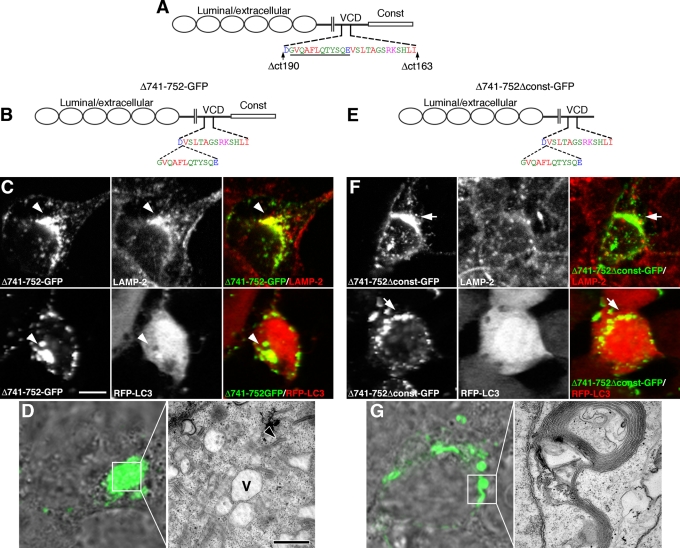

Thus removal of the constant domain, or the constant domain plus an additional 39 amino acids into the VCD (Δct163-GFP), resulted in multivesicular and tubular organelles that were similar in size and LAMP-2/RFP-LC3 colocalization as those associated with full-length Pcdh-γA3. Deletion of the constant domain plus 65 additional VCD residues (Δct190-GFP) completely abrogated targeting to LAMP-2/RFP-LC3–positive organelles and resulted in membrane whorls when found intracellularly. These results suggest that a 26–amino acid segment bounded by the truncation points within the Δct163 and Δct190 constructs controls trafficking of Pcdh-γA3 (Figure 8A), as truncation within this segment (Δct183) partially disrupted trafficking. It remained possible that the differences in trafficking observed for the truncation constructs were a result of shortening the molecule. To address this, we excised 12 amino acids from the amino-terminal end of the 26–amino acid segment within the context of the intact molecule (Δ741-752-GFP; Figure 8B) or as a constant-domain-deleted version (Δ741-752Δconst-GFP; Figure 8E) and determined the ability of these constructs to colocalize with LAMP-2 and RFP-LC3 (Figure 8, C and F) or analyzed their associated organelles by CLEM (Figure 8, D and G). The Δ741-752-GFP construct colocalized with LAMP-2 in a perinuclear distribution similar to intact γA3-GFP but only weakly recruited RFP-LC3 (Figure 8C, arrowheads). By CLEM, Δ741-752-GFP was associated with large vacuoles (Figure 8D, V) with the occasional tubule (Figure 8D, arrowhead). These organelles strongly resembled those associated with intact γA3-GFP under conditions of lysosomal disruption (Hanson et al., 2010a). In contrast, Δ741-752Δconst-GFP never colocalized with LAMP-2 or RFP-LC3 (Figure 8F, arrows), and CLEM of its associated organelles revealed whorled membranes. Therefore internal disruption of the 26–amino acid VCD segment can disrupt trafficking of Pcdh-γA3, although additional sequences within the constant domain also perform some trafficking functions.

FIGURE 8:

Internal deletion within a 26–amino acid VCD segment disrupts trafficking. (A) Location of the 26–amino acid segment in Pcdh-γA3 bounded by the Δct163 and Δct190 truncations. Underlined is the location of 12–amino acid excision in (B) full-length and (E) constant-domain-deleted Pcdh-γA3-GFP (Δ741-752-GFP and Δ741-752Δconst-GFP, respectively). Δ741-752-GFP colocalized with LAMP-2 (C) in a perinuclear manner but only weakly coclustered RFP-LC3 (C). In contrast, Δ741-752Δconst-GFP lacked both LAMP-2 colocalization (F) and RFP-LC3 clustering activity (F). By CLEM, Δ741-752-GFP (D) corresponded to enlarged vacuoles that resembled disrupted lysosomes (V), with very few tubules (arrowhead). CLEM of Δ741-752Δconst-GFP (G) revealed that this construct was associated with membrane whorls. Bar,10 μm in C and F; 5 μm in light images in D and G; and 500 nm in EM images.

The VCD can promote targeting to Pcdh-γ–positive organelles in neurons

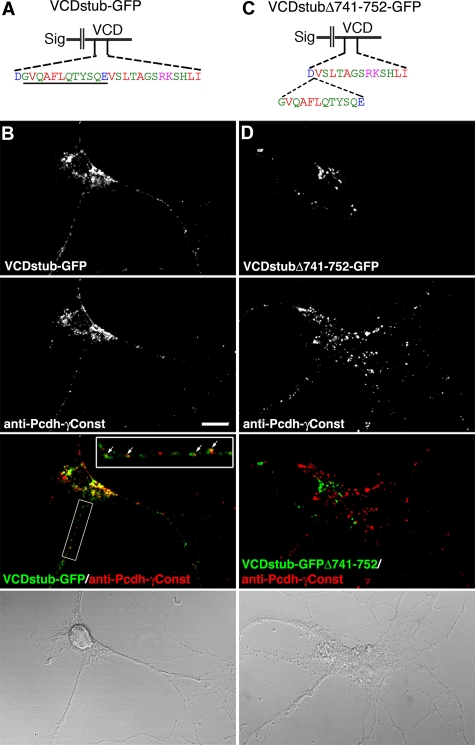

In neurons, endogenous Pcdh-γs are located in organelles in axons and dendrites, with a fraction at or near synaptic junctions (Phillips et al., 2003; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009, 2010). We sought to determine whether the VCD contains sufficient signals for trafficking to Pcdh-γ–positive organelles. To do this, we deleted the luminal/extracellular domain, replacing it with a signal sequence, followed by the transmembrane domain and VCD of Pcdh-γA3 and lacking the constant domain (VCDstub-GFP; Figure 9A). We also generated the same construct with the 12–amino acid excision in the proximal part of the 26–amino acid critical VCD segment (VCDstubΔ741-752-GFP; Figure 9C). These were nucleofected into dissociated hippocampal neurons, and localization was compared with endogenous Pcdh-γs at 7 d in vitro by immunostaining with anti–Pcdh-γ constant-domain antibodies that do not react with either construct. VCDstub-GFP (Figure 9B) was expressed in axons, dendrites, and the cell body in a punctate pattern that partially overlapped with endogenous Pcdh-γs (Figure 9B, inset, arrowheads). Other VCDstub-GFP puncta did not colocalize with endogenous Pcdh-γs. In contrast, VCDstubΔ741-752-GFP was expressed almost exclusively within the cell body and proximal dendrites in a punctate pattern (Figure 9D, arrowheads), with no expression in distal axons and dendrites and no colocalization with endogenous Pcdh-γs. Thus the VCD contains targeting sequences that allow trafficking to some Pcdh-γ positive compartments in axons and dendrites; disruption of this dramatically alters trafficking in neurons.

FIGURE 9:

The VCD can mediate targeting to Pcdh-γ–positive organelles. (A) Constructs containing only an extracellular signal sequence, transmembrane domain, and intact (VCDstub-GFP) or disrupted (Δ741-752VCDstub-GFP) VCD of Pcdh-γA3. In cultured hippocampal neurons at 7 d in vitro VCDstub-GFP (B) was expressed in the soma with fine organelles extending into neurites, whereas VCDstubΔ741-752-GFP (C) remained largely within the cell body. Immunostaining for endogenous Pcdh-γs with an anti–Pcdh-γ constant domain antibody that recognizes the Pcdh-γ constant domain (red channel), missing in the VCDstub constructs, revealed partial colocalization with VCDstub-GFP (B, inset, arrowheads ) and a lack of colocalization with VCDstubΔ741-752-GFP (C). Bar, 10 μm.

The Pcdh-γB2 VCD also directs trafficking

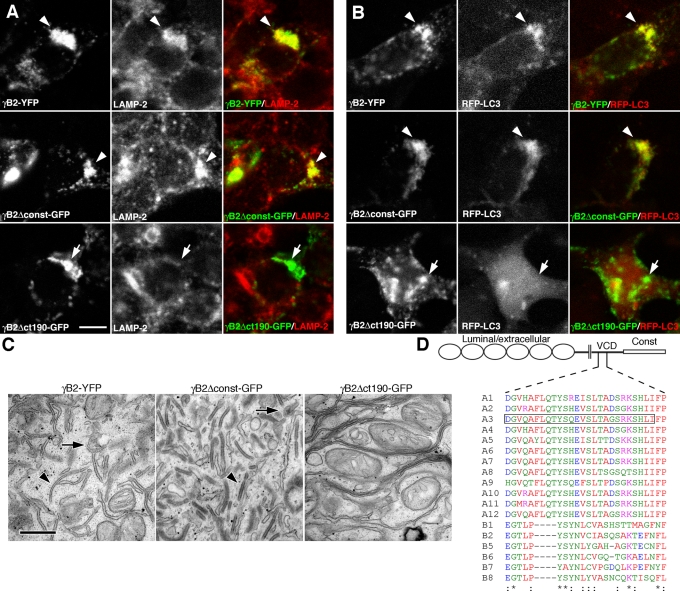

The 26–amino acid segment bounded by the Δct190-GFP and Δct163-GFP truncations in Pcdh-γA3 (Figure 10D, box) is conserved among Pcdh-γAs. Pcdh-γBs also share some similarities in this region (Figure 10D), suggesting that the Pcdh-γB VCD also contains critical targeting sequences. We evaluated the full-length γB2–yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), the constant-domain-deleted γB2Δconst-GFP, and the constant plus most of the VCD-deleted γB2ctΔ190-GFP (Figure 1G) for their ability to colocalize with LAMP-2 and RFP-LC3 and for their associated organelles by CLEM. Both γB2-YFP and γB2Δconst-GFP colocalized with LAMP-2 and recruited RFP-LC3 (Figure 10, A and B, arrowheads), whereas γB2ctΔ190-GFP lacked colocalization with both LAMP-2 and RFP-LC3 (Figure 10, A and B, arrows). By CLEM, γB2-YFP and γB2Δconst-GFP corresponded to tubules and ∼170-nm multivesicular organelles (Figure 10C), whereas γB2ctΔ190-GFP corresponded to membrane sheets or whorls. Thus the VCD from a Pcdh-γB family member also participates in trafficking.

FIGURE 10:

Pcdh-γB2 VCD is necessary for trafficking of Pcdh-γB2. Full-length γB2-YFP colocalized with LAMP-2 (A) and coclustered with RFP-LC3 (B) as shown previously. Constant-domain-deleted Pcdh-γB2 (γB2Δconst-GFP) also colocalized with LAMP-2 and RFP-LC3. Truncation of most of the VCD (γB2Δct190-GFP) caused the molecule to no longer colocalize with LAMP-2 and RFP-LC3 (A and B, bottom). (C) γB2-YFP and γB2Δconst-GFP both were associated with tubules and multivesicular organelles (arrowheads), whereas γB2Δct190-GFP was associated with disorganized membrane whorls or stacks. (D) Manually adjusted clustal alignment of VCD segments from Pcdh-γAs and Pcdh-γBs. The critical 26–amino acid segment in Pcdh-γA3 is boxed. Bar, 10 μm in A and B and 500 nm in C.

DISCUSSION

The cell biological function of the Pcdhs has been poorly defined since their discovery in 1998–1999 (Kohmura et al., 1998; Wu and Maniatis, 1999). Although Pcdhs can participate in cell–cell interactions (Obata et al., 1995) and have homophilic properties (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010), the intracellular distribution, both of endogenous (Phillips et al., 2003; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2010) and overexpressed Pcdhs (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009, F2010; Hanson et al., 2010a), is different (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2010) than that of the surface-expressed classical cadherins. It is likely that intracellular retention or endocytosis and endolysosomal trafficking of Pcdhs (Phillips et al., 2003; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009, 2010; Buchanan et al., 2010; Hanson et al., 2010a; Schalm et al., 2010) reflect a nonconventional role for these adhesive-like molecules in neural development and cell survival. It is tempting to speculate that the Pcdhs, and in particular the Pcdh-γs, couple organelle trafficking in late endosomes or lysosomes to cell–cell interactions. Such a mechanism might eventually explain the phenotypes of neural cell death upon Pcdh-γ knockout.

For the classic cadherins, it has been shown that cytoplasmic interactions, primarily with the catenin proteins (Aberle et al., 1996), but also other molecules (Gorski et al., 2005), are important for their adhesive function. Because the 14 Pcdh-αs and the 22 Pcdh-γs all have a large common cytoplasmic moiety, it is believed that these constant cytoplasmic domains probably contain the most important sequences for signal transduction by these molecules. For this reason, most attention has been paid to the Pcdh-α (Kohmura et al., 1998) and Pcdh-γ (Chen et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010) constant domains to identify cytoplasmic interactions for these molecules. Of interest, despite the low similarity of the Pcdh-α and Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domains, both bind to FAK and PYK kinases (Chen et al., 2009), and it has been suggested that Pcdh-αs and Pcdh-γs perform overlapping functions (Han et al., 2010). The knockout phenotypes of Pcdh-αs (Katori et al., 2009) and Pcdh-γs (Wang et al., 2002), however, as well as their distinct subcellular trafficking routes (Hanson et al., 2010a), point to different functions subserved by the two Pcdh families.

Inactivation of the entire Pcdh-γ locus caused cell death in spinal cord and retinal interneurons, with likely effects in additional neuron types (Wang et al., 2002; Lefebvre et al., 2008). In contrast, deletion of only the carboxy-terminal 57 amino acids (Weiner et al., 2005), approximating the distal half of the constant domain, no longer caused increased cell death, indicating that sequences that mediate a cell survival function for Pcdh-γs may be located in the proximal portion of the constant domain or within the VCD regions of the individual Pcdh-γ genes. Elucidation of these sequences will likely be critical to understanding the function of Pcdh-γs, and the present study provides a solid framework in which to address the issue. It is possible that the cell survival function might in some way be connected to trafficking in the endosome/lysosome pathway, given recent connections between lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death (Boya et al., 2003; Jaattela et al., 2004; Kroemer and Jaattela, 2005; Gyrd-Hansen et al., 2006; Kreuzaler et al., 2011) and the connection between lysosome dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Nixon et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010).

A functional readout for Pcdh activity in vitro has been elusive. For classic cadherins, the assay for function is aggregation of transfected cells in vitro (Nose et al., 1988). However, Pcdh-γs have weak cellular aggregation in cells (Obata et al., 1995) when compared with classic cadherins, making study of their function difficult. Replacement of the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain with that of N-cadherin greatly enhanced aggregation (Obata et al., 1995), consistent with a negative effect on cell–cell interactions by the cytoplasmic domain. Deletion of the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain shifted the molecule from an intracellular to a surface distribution at cell–cell contacts (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009), further revealing Pcdh-γ adhesive activity and allowing its characterization (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). All of the studies to date clearly indicate that the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain has intracellular retention activity, and this must be crucial for the function of the molecule in vivo. In contrast to the Pcdh-γs, the Pcdh-αs, whether a full-length or cytoplasmic deletion, appear to lack any detectable homophilic adhesive activity but may bind to integrins through an RGD sequence (Mutoh et al., 2004).

It was shown that GFP-tagged Pcdh-γs are fully functional in vivo (Wang et al., 2002; Weiner et al., 2005; Lefebvre et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2008; Han et al., 2010; Su et al., 2010). Thus an effective functional assay for Pcdh-γ distribution, trafficking, and function is CLEM (Polishchuk et al., 2000; Mironov and Beznoussenko, 2009; Razi and Tooze, 2009; Hanson et al., 2010b) of GFP-tagged Pcdh-γs in tissue culture cells and primary neurons. The intracellular location of Pcdh-γ GFP fusions (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009, 2010; Hanson et al., 2010a), which mimics the intracellular distribution of Pcdh-γs in vivo (Phillips et al., 2003; Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2010), can be determined precisely at the light and electron microscopic (EM) levels and the effect of molecular perturbations evaluated. By CLEM, Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain–mediated intracellular retention was reflected in trafficking to late endosomes or lysosomes of the full-length molecule; retention of the cytoplasmic deleted molecules, when found, was in the form of ER-associated whorls (Hanson et al., 2010a). Furthermore, in CAD cells, full-length Pcdh-αs and Pcdh-γs are prominently associated with endocytic and lysosomal processes (Buchanan et al., 2010; Schalm et al., 2010). Using CLEM, we now show that much of the Pcdh-γ intracellular retention activity is located in the VCD, with the constant domain playing a separate role in Pcdh-γ trafficking.

The present study now shows that proper Pcdh-γ trafficking requires sequences within the VCD. Our results, coupled with Pcdh-γ truncation in vivo (Weiner et al., 2005), point to the VCD as a possible mediator of cytoplasmic interactions relevant to the cell survival function of Pcdh-γs. Deletion of the carboxy-terminal 57 amino acids, corresponding to almost half of the constant domain but not including any VCD residues, caused no increased cell death, in contrast to deletion of the whole locus (Weiner et al., 2005). By comparison, we show that removal of the constant domain did not substantially affect trafficking to late endosomal/lysosomal pathway, whereas disruption of the VCD did disrupt trafficking. Furthermore, the VCDs between Pcdh-γA and Pcdh-γB families have similar motifs. It is likely that the VCD mediates interactions with cytosolic proteins that govern trafficking in the endosome/lysosome pathway, of which there are many possible candidates. Once trafficked to appropriate organelles, tubulation could then be induced by interactions within the lumen. Further elucidation of the function and interactions of Pcdh-γ VCDs will shed additional light on how Pcdh-γs affect cell surface interactions, intracellular trafficking, and cell survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA constructs

Plasmids encoding full length Pcdh-γA3-GFP, constant-domain-deleted Pcdh-γA3 (Δconst-GFP), and a constant domain plus an additional VCD 66–amino acid deletion (referred to here as Δct190-GFP) have been described (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009). RFP-LC3 was provided by Zhenyu Yue (Mount Sinai School of Medicine). Pcdh-γA3-GFP used in this study has a mutated XbaI site at 1313 base pairs from the translation start site sequence, rendering the other XbaI site at 2357 base pairs unique (Figure 1, arrow). This downstream XbaI site and the AgeI site in pEGFP-N1 were used to append cytoplasmic segments of interest by PCR cloning. Cytoplasmic segments from Pcdh-α1 and N-cadherin, initiated at sites approximately equidistant from the transmembrane region as the cloning site in Pcdh-γA3, were generated by PCR and cloned into the XbaI site of Pcdh-γA3-GFP and the AgeI site of pEGFP-N1, producing the γA3/α1-GFP and γA3/N-GFP chimeric molecules, respectively (Figure 1). The junction sites are as follows (Pcdh-γA3 residues are in boldface): γA3/α1-GFP, FVGLDSYSQQ; γA3/N-GFP, FVGLDPEDDV.

Pcdh-γA3 with most of the VCD excised (ΔVCD-GFP) was generated by amplification of Pcdh-γA3-GFP template with GCGTCTAGATCAAGCCCCGCCCAACACTGACTGG and GCGACCGGTCCCTTCTTCTCTTTCTTGCCCG and subcloning into the downstream XbaI site in Pcdh-γA3-GFP and the AgeI site in pEGFP-N1. Pcdh-γA3-GFP plasmids with a 12–amino acid excision in the VCD were generated by PCR amplification using the following primers: GCGTCTAGATGTTTCACTTACCGCAGGCTCTCGG and GCGACCGGTCCCTTCTTCTCTTTCTTGCCCG for the full-length version (Δ741-752-GFP) or GCGTCTAGATGTTTCACTTACCGCAGGCTCTCGG and GCGACCGGTCCCTGAGGCAGCGTGGGGTCTTC for the constant-domain-deleted version (Δ741-751Δconst-GFP). These amplification products were cloned into the downstream XbaI site in Pcdh-γA3-GFP and the AgeI site in pEGFP-N1. To generate the VCDstub-GFP construct, the VCD was subcloned as an XbaI/AgeI fragment from Δconst-GFP construct into the XbaI and AgeI sites of the luminal/extracellular deleted Pcdh-γA3 obtained from Marcus Frank and Ingrid Haas (Haas et al., 2005). To generate the VCDstubΔ741-752-GFP construct, the 12–amino acid deleted VCD segment was subcloned as an XbaI/AgeI fragment from Δ741-751Δconst-GFP into the XbaI and AgeI sites of the luminal/extracellular deleted Pcdh-γA3-GFP.

The Δct163-GFP and Δct183-GFP constructs were generated by amplification of a Pcdh-γA3 template with GTGGGTCTAGATGGGGTC and GCGACCGGTCCGATCAGGTGACTCTTCCG for Δct163-GFP or GGCAGTGGCTGTGGTCTCCTGC and GCGACCGGTCCGAAAGCTTGCACCCC for Δct183-GFP. Products were cloned into the XbaI and AgeI sites of Pcdh-γA3-GFP.

Pcdh-γB2-YFP was generously provided by Joshua Weiner. Intracellular deleted Pcdh-γB2-GFP (referred to here as γB2Δct190-GFP) was generated as described (Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2009). Constant-domain-deleted Pcdh-γB2-GFP was generated by PCR amplification of the Pcdh-γB2-YFP template using GCGCTACCGGACTCAGATCTCGAGCTC and GCGGAATTCCCTTTGAGATAGAATCCGAGAC as primers. The products were subcloned into the XhoI and EcoRI sites of pEGFP-N1.

Antibodies

Antibodies to Pcdh-γA3 (Phillips et al., 2003), Pcdh-α1 (Hanson et al., 2010a), and N-cadherin (Phillips et al., 2001) cytoplasmic domains have been described. A monoclonal antibody to the Pcdh-γ constant domain (clone N159/5) was obtained from the University of California, Davis/National Institutes of Health NeuroMab Facility. Monoclonal anti-LAMP-2 (H4B4, developed by J. T. August and J. E. K. Hildreth) was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the Department of Biology, University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA).

Cell culture, transfection, immunostaining, and CLEM

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were plated on 35-mm live-imaging dishes with gridded glass bottoms (MatTek, Ashland, MA) for analysis by CLEM. Cells were plated on 25-mm coverslips in six-well plates for light microscopy alone. Primary neurons were nucleofected with indicated constructs and cultured on coverslips or nongridded live-imaging dishes (MatTek) as described (Reilly et al., 2011). HEK293 cells were transfected with 4 μg of each plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. For RFP-LC3 cotransfections, cells were fixed the next day with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, and mounted. For LAMP-2 or Pcdh-γ immunostaining, coverslips were fixed and immunostained as described (Hanson et al., 2010a). For CLEM, cells in live-imaging dishes were imaged on an LSM 510 META microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and processed as described (Hanson et al., 2010a, 2010b). Immunostained coverslips were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 410 microscope as described (Hanson et al., 2010a). Organelle morphology associated with each construct was confirmed in two to four different cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS051238 and an Irma T. Hirschl Award to G.R.P. We thank Joshua Weiner, Marcus Frank, Ingrid Haas, and Zhenyu Yue for gifts of reagents.

Abbreviation used:

- CLEM

correlative light and electron microscopy

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- LC3

MAP1A/1B light chain 3

- Pcdh

protocadherin

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- VCD

variable cytoplasmic domain

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0283) on September 14, 2011.

REFERENCES

- Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:514–523. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4%3C514::AID-JCB4%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Andreau K, Poncet D, Zamzami N, Perfettini JL, Metivier D, Ojcius DM, Jaattela M, Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization induces cell death in a mitochondrion-dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1323–1334. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SM, Schalm SS, Maniatis T. Proteolytic processing of protocadherin proteins requires endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17774–17779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013105107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lu Y, Meng S, Han MH, Lin C, Wang X. alpha- and gamma-Protocadherins negatively regulate PYK2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2880–2890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807417200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Kang S, Phillips GR. gamma-Protocadherin homophilic interaction and intracellular trafficking is controlled by the cytoplasmic domain in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Oung T, Hanson HH, O'Leary R, Janssen WG, Dolios G, Wang R, Phillips GR. gamma-Protocadherins are enriched and transported in specialized vesicles associated with the secretory pathway in neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:921–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Gomez LL, Scott JD, Dell'Acqua ML. Association of an A-kinase-anchoring protein signaling scaffold with cadherin adhesion molecules in neurons and epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3574–3590. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyrd-Hansen M, et al. Apoptosome-independent activation of the lysosomal cell death pathway by caspase-9. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7880–7891. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00716-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas IG, Frank M, Veron N, Kemler R. Presenilin-dependent processing and nuclear function of gamma-protocadherins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9313–9319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Lin C, Meng S, Wang X. Proteomics analysis reveals overlapping functions of clustered protocadherins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:71–83. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900343-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson HH, Kang S, Fernandez-Monreal M, Oung T, Yildirim M, Lee R, Suyama K, Hazan RB, Phillips GR. LC3-dependent intracellular membrane tubules induced by gamma-protocadherins A3 and B2: A role for intraluminal interactions. J Biol Chem. 2010a;285:20982–20992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson HH, Reilly JE, Lee R, Janssen WG, Phillips GR. Streamlined embedding of cell monolayers on gridded live imaging dishes for correlative light and electron microscopy. Microsc Microanal. 2010b;20:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1431927610094092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaattela M, Cande C, Kroemer G. Lysosomes and mitochondria in the commitment to apoptosis: a potential role for cathepsin D and AIF. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:135–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katori S, Hamada S, Noguchi Y, Fukuda E, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto H, Hasegawa S, Yagi T. Protocadherin-alpha family is required for serotonergic projections to appropriately innervate target brain areas. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9137–9147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5478-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohmura N, Senzaki K, Hamada S, Kai N, Yasuda R, Watanabe M, Ishii H, Yasuda M, Mishina M, Yagi T. Diversity revealed by a novel family of cadherins expressed in neurons at a synaptic complex. Neuron. 1998;20:1137–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzaler PA, Staniszewska AD, Li W, Omidvar N, Kedjouar B, Turkson J, Poli V, Flavell RA, Clarkson RW, Watson CJ. Stat3 controls lysosomal-mediated cell death in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:303–309. doi: 10.1038/ncb2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Jaattela M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:886–897. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, et al. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell. 2010;141:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre JL, Zhang Y, Meister M, Wang X, Sanes JR. g-Protocadherins regulate neuronal survival but are dispensable for circuit formation in retina. Development. 2008;135:4141–4151. doi: 10.1242/dev.027912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Meng S, Zhu T, Wang X. PDCD10/CCM3 acts downstream of g-protocadherins to regulate neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41675–41685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood D, Schuck S, Ferguson C, Gerl MJ, Simons K. Generation of cubic membranes by controlled homotypic interaction of membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12041–12048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900220200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov AA, Beznoussenko GV. Correlative microscopy: a potent tool for the study of rare or unique cellular and tissue events. J Microsc. 2009;235:308–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2009.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh T, Hamada S, Senzaki K, Murata Y, Yagi T. Cadherin-related neuronal receptor 1 (CNR1) has cell adhesion activity with beta1 integrin mediated through the RGD site of CNR1. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:494–508. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA, Yang DS, Lee JH. Neurodegenerative lysosomal disorders: a continuum from development to late age. Autophagy. 2008;4:590–599. doi: 10.4161/auto.6259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose A, Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Expressed recombinant cadherins mediate cell sorting in model systems. Cell. 1988;54:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata S, Sago H, Mori N, Rochelle JM, Seldin MF, Davidson M, St John T, Taketani S, Suzuki ST. Protocadherin Pcdh2 shows properties similar to, but distinct from, those of classical cadherins. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3765–3773. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GR, et al. The presynaptic particle web: ultrastructure, composition, dissolution, and reconstitution. Neuron. 2001;32:63–77. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GR, Tanaka H, Frank M, Elste A, Fidler L, Benson DL, Colman DR. Gamma-protocadherins are targeted to subsets of synapses and intracellular organelles in neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5096–5104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05096.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polishchuk RS, Polishchuk EV, Marra P, Alberti S, Buccione R, Luini A, Mironov AA. Correlative light-electron microscopy reveals the tubular-saccular ultrastructure of carriers operating between Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:45–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad T, Wang X, Gray PA, Weiner JA. A differential developmental pattern of spinal interneuron apoptosis during synaptogenesis: insights from genetic analyses of the protocadherin-g gene cluster. Development. 2008;135:4153–4164. doi: 10.1242/dev.026807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razi M, Tooze SA. Correlative light and electron microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:261–275. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JE, Hanson HH, Phillips GR. Persistence of excitatory shaft synapses adjacent to newly emerged dendritic protrusions. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalm SS, Ballif BA, Buchanan SM, Phillips GR, Maniatis T. Phosphorylation of protocadherin proteins by the receptor tyrosine kinase Ret. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13894–13899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007182107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner D, Weiner JA. Combinatorial homophilic interaction between gamma-protocadherin multimers greatly expands the molecular diversity of cell adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14893–14898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004526107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Marcheva B, Meng S, Liang FA, Kohsaka A, Kobayashi Y, Xu AW, Bass J, Wang X. Gamma-protocadherins regulate the functional integrity of hypothalamic feeding circuitry in mice. Dev Biol. 2010;339:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic B, Nabholz CE, Baldwin KK, Kim Y, Rueckert EH, Ribich SA, Cramer P, Wu Q, Axel R, Maniatis T. Promoter choice determines splice site selection in protocadherin alpha and gamma pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2002;10:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Weiner JA, Levi S, Craig AM, Bradley A, Sanes JR. Gamma protocadherins are required for survival of spinal interneurons. Neuron. 2002;36:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JA, Wang X, Tapia JC, Sanes JR. Gamma protocadherins are required for synaptic development in the spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407931101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Maniatis T. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell. 1999;97:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]