Summary

During the early stages of body axis extension, retinoic acid (RA) synthesized in somites by Raldh2 represses caudal fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling to limit the tailbud progenitor zone. Excessive RA down-regulates Fgf8 and triggers premature termination of body axis extension, suggesting that endogenous RA may function in normal termination of body axis extension. Here, we demonstrate that Raldh2−/− mouse embryos undergo normal down-regulation of tailbud Fgf8 expression and termination of body axis extension in the absence of RA. Interestingly, Raldh2 expression in wild-type tail somites and tailbud from E10.5 onwards does not result in RA activity monitored by retinoic acid response element (RARE)-lacZ. Treatment of wild-type tailbuds with physiological levels of RA or retinaldehyde induces RARE-lacZ activity, validating the sensitivity of RARE-lacZ and demonstrating that deficient RA synthesis in wild-type tail somites and tailbud is due to a lack of retinaldehyde synthesis. These studies demonstrate an early uncoupling of RA signaling from mouse tailbud development and show that termination of body axis extension occurs in the absence of RA signaling.

Keywords: body axis termination, retinoic acid, retinaldehyde, somitogenesis, Raldh2, Fgf8, Mesp2, RARE-lacZ

Vertebrate embryos develop in an anterior to posterior direction through the process of body axis extension from a caudal progenitor zone (Cambray and Wilson, 2002). As the body axis extends, the paraxial mesoderm generated is sequentially segmented into somites that generate the vertebrae and other components of the axial skeleton as well as skeletal muscle (Dequeant and Pourquie, 2008). Species-specific differences in the number of somites results in a wide variety of body axis lengths among vertebrate animals. For instance, the final number of somites varies from 62–65 in mouse embryos, whereas human embryos have 38–39 somites, chick embryos have 51–53 somites, and snake embryos have several hundred somites (Richardson et al., 1998). Soon after the process of somitogenesis is completed, body axis extension is terminated. The control of segment number across vertebrate embryos has been shown to involve a similar clock-and-wavefront mechanism with variations in the rate of the segmentation clock relative to the developmental rate (Gomez et al., 2008).

The mechanism that terminates body axis extension and hence determines the final segment number is unknown. Somitogenesis and growth of the caudal progenitor zone requires fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling (Wahl et al., 2007). Thus, the mechanism that terminates body axis extension may involve down-regulation of caudal FGF signaling at a species-specific point in development. Retinoic acid (RA) is a vitamin A derivative that when administered at high doses to mouse embryos can alter vertebral identity and prematurely terminate body axis extension (Iulianella et al., 1999; Kessel and Gruss, 1991). As a safeguard against premature termination of body axis extension, the caudal tip of the tailbud expresses Cyp26a1 which encodes a cytochrome P450 enzyme that can degrade RA (White et al., 1996). Genetic loss of Cyp26a1 function results in the encroachment of RA activity into the caudal progenitor zone after E8.5, resulting in loss of Fgf8 expression and premature termination of body axis extension including loss of the tail and sometimes lumbar/sacral truncations (Abu-Abed et al., 2001; Sakai et al., 2001). RA has been shown to antagonize expression of Fgf8 in the caudal progenitor zone during body axis extension in chick and mouse embryos (Del Corral et al., 2003). RA synthesized in presomitic mesoderm and somites by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (Raldh2) is essential for proper somitogenesis and body axis extension, potentially through its ability to repress Fgf8 at the anterior border of the caudal progenitor zone during the early stages of somitogenesis (Sirbu and Duester, 2006; Vermot and Pourquié, 2005; Vermot et al., 2005). The requirement for Raldh2 to repress caudal Fgf8 was reported to occur only during the early stages of somitogenesis in mouse when the expression domains of these genes overlap or are in very close proximity (Sirbu and Duester, 2006). Thus, during the middle stages of somitogenesis, the Raldh2 and Fgf8 expression domains may be too far apart for RA signaling to play a role in Fgf8 regulation. Examination of corn snake embryos (which develop ~315 somites) demonstrated that Raldh2 is still expressed in caudal somites at the 260-somite stage in opposition to Fgf8 expressed in the tailbud caudal progenitor zone; however, a sizable gap exists between the two domains (Gomez et al., 2008). It is unclear whether a natural increase in RA activity at a late point in development could decrease Fgf8 expression sufficiently to trigger the termination of body axis extension.

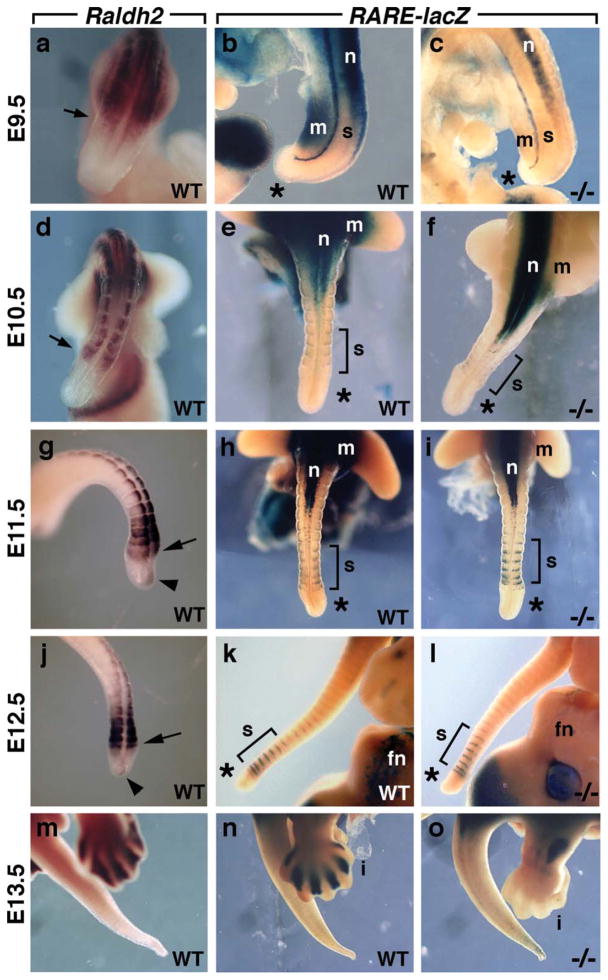

Recent studies in chick embryos demonstrated an increase in tailbud Raldh2 expression and detection of tailbud RA activity near the end of somitogenesis, suggesting that RA may play a role in termination of body axis extension; however, in those same studies, it was reported that mouse tailbuds exhibit much less Raldh2 expression and RA activity was not detected (Tenin et al., 2010). Here, we demonstrated that mouse Raldh2 expression is found in caudal somites from E9.5–E12.5, but is down-regulated by E13.5 when body axis extension ends (Fig. 1a,d,g,j,m). Similar to previous studies (Tenin et al., 2010), we observed that Raldh2 expression intensified in the caudal-most somites from E11.5–E12.5, plus a small expression domain was observed further caudally in the tailbud during these stages (Fig. 1g,j). We used Raldh2−/− mouse embryos to address the issue of whether RA is required for termination of body axis extension in the tailbud which occurs between E12.5–E13.5. Although Raldh2−/− embryos normally die at E9.5 (Niederreither et al., 1999), we have previously shown that Raldh2−/− embryos rescued with a small dose of RA before E9.5 survive early lethality and grow to E13.5, thus allowing analysis of Raldh2 function in tissues of older embryos (Brade et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2010). First, we analyzed Raldh2−/− embryos carrying the retinoic acid response element (RARE)-lacZ RA-reporter transgene (Rossant et al., 1991) to determine where endogenous RA signaling is occurring from time points well before body axis termination up until E13.5 when termination has occurred. In E9.5 wild-type embryos, we observed RARE-lacZ expression in caudal lateral plate mesoderm and intermediate mesoderm/mesonephros (although not newly generated somites), while E9.5 Raldh2−/− embryos lost most caudal mesodermal RARE-lacZ expression (Fig. 1a–c); the remaining RARE-lacZ expression has been shown to be due to enzymes other that Raldh2, such as Raldh3 which is responsible for RA activity remaining in the mesonephros (Zhao et al., 2009) although it remains unclear what is responsible for RA activity remaining in the neural tube. Interestingly, in E10.5 wild-type embryos RARE-lacZ expression was clearly not observed in the caudal-most somites even though they expressed Raldh2; E10.5 Raldh2−/− embryos were similar except that they have lost RARE-lacZ expression in hindlimb mesoderm (Fig. 1d–f). In wild-type embryos at E11.5-E12.5, RARE-lacZ expression was not detected in the tailbud even though a small domain of Raldh2 expression exists in the tailbud itself; also, despite high Raldh2 expression in the caudal-most somites we observed only thin stripes of RARE-lacZ expression in portions of the caudal-most 6 somites (Fig. 1g,h,j,k). Raldh2−/− embryos at E11.5–E12.5 retained the thin stripes of somite RARE-lacZ expression, demonstrating that Raldh2 is not responsible, but these mutants lost RARE-lacZ expression in other tissues such as the hindlimb mesoderm (E11.5) and frontonasal mass (E12.5) that are known to receive RA from nearby tissues expressing Raldh2 (Fig. 1i,l). At E13.5, expression of Raldh2 and RARE-lacZ was not observed in wild-type tails; RARE-lacZ expression was nearly eliminated in Raldh2−/− tails and was completely lost in the hindlimb interdigital regions associated with Raldh2 expression (Fig. 1m–o). Our findings demonstrate that the thin stripes of RARE-lacZ expression observed in tail somites are due to some unidentified activity since they are unchanged in Raldh2−/− tails. Together, these observations suggest that RA signaling does not correlate with termination of body axis extension, and these findings provide the first evidence that tissues expressing Raldh2 may not always generate RA.

FIG. 1.

RA synthesis and signaling during the late stages of body axis extension. (a, d, g, j, m) Detection of Raldh2 mRNA by in situ hybridization; arrows mark newly formed somites; arrowheads mark Raldh2 expression in the tailbud. (b, c, e, f, h, i, k, l, n, o) Detection of RA signaling activity in wild-type or Raldh2−/− embryos carrying RARE-lacZ; brackets mark caudal somites with either no RA activity or very thin stripes of RA activity; asterisks indicate a lack of RA activity in the tailbud; n = 3 for all Raldh2−/− specimens. fn, frontonasal mass; i, interdigital mesenchyme; m, mesoderm (lateral plate and intermediate-mesonephros); n, neural tube; s, somite.

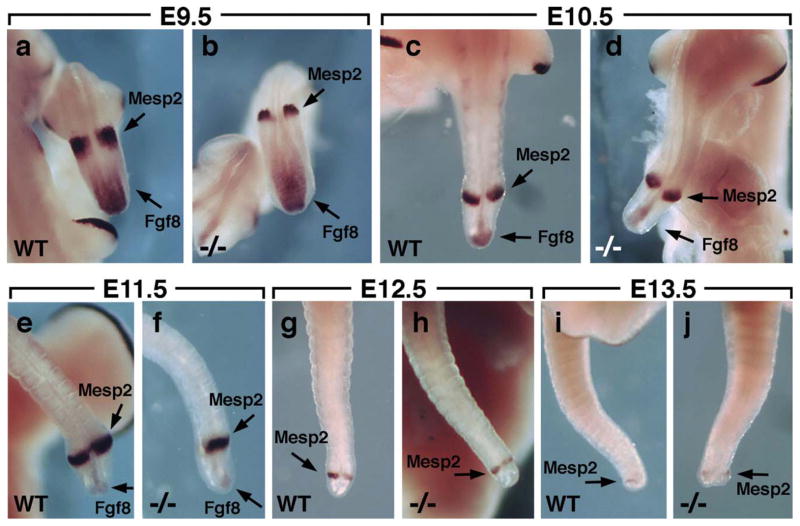

To examine more closely whether Raldh2 is required for termination of body axis extension, we examined embryos from E9.5–E13.5 for expression of Fgf8 which marks the caudal progenitor zone and Mesp2 which marks a small region of anterior presomitic mesoderm where each new somite is generated (Morimoto et al., 2005). In both wild-type and Raldh2−/− embryos, Mesp2 expression was observed at high levels from E9.5–E11.5, at a lower level on E12.5, and expression was almost undetectable at E13.5 when body axis extension has terminated (Fig. 2a–j). Caudal Fgf8 expression was also similar in wild-type and Raldh2−/− embryos, with high level expression observed at E9.5, a reduction at E10.5–E11.5, and essentially no expression at E12.5–E13.5 when the caudal progenitor zone disappears (Fig. 2a–j). We can conclude that as early as E9.5 Raldh2 is not required to limit the anterior extent of the caudal Fgf8 expression zone. As we observed no difference in Mesp2 or Fgf8 expression between wild-type and Raldh2−/− embryos (in particular no increase of Mesp2 expression in the mutant), we conclude that Raldh2 is not required for termination of either somitogenesis or body axis extension.

FIG. 2.

Raldh2 is not required for termination of body axis extension. (a–j) Wild-type and Raldh2−/− embryos from E9.5–E13.5 were subjected to double in situ hybridization with probes for both Fgf8 and Mesp2 as indicated by arrows; n = 2 for all Raldh2−/− specimens.

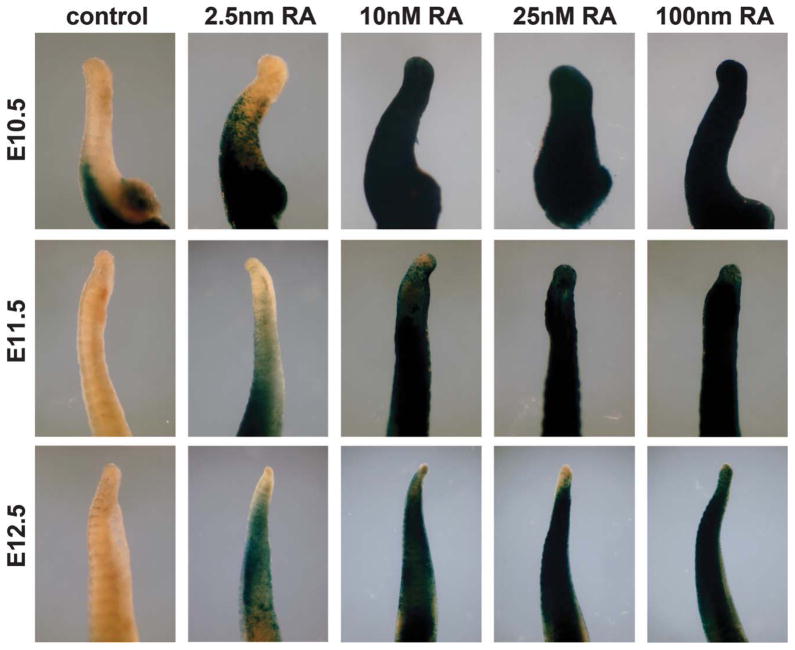

To further investigate our earlier observation, suggesting that no correlation exists between expression of Raldh2 and RARE-lacZ in caudal somites and tailbud, we sought to validate the sensitivity of RARE-lacZ in these tissues. Previous RA measurements in E10.5–E13.5 mouse embryos using HPLC detection have demonstrated that endogenous RA levels range from 1–100 nM in various tissues (Horton and Maden, 1995) with the average concentration of RA in a whole E10.5 embryo being 25 nM (Mic et al., 2003). We designed experiments to determine whether an absence of RARE-lacZ expression in the caudal somites and tailbud can be confidently used to conclude that endogenous RA is absent or below physiological levels. Tails from E10.5–E12.5 wild-type embryos carrying RARE-lacZ were cultured in the presence of physiological doses of RA (2.5 nM, 10 nM, 25 nM, or 100 nM), then stained for RARE-lacZ expression to detect RA activity. Whereas untreated control tails exhibited no RARE-lacZ expression in the tailbud or caudal somites (except for very weak detection between the somites), we found that as little as 2.5 nM RA induced RARE-lacZ expression in the caudal somites but not the tailbud of E10.5–E12.5 tails (see Fig. 3). Treatment with 10 nM RA resulted in high RARE-lacZ expression in the tailbud at E10.5, and lower expression in the tailbud at E11.5–E12.5; treatment with 25 or 100 nM induced RARE-lacZ expression throughout the tail and tailbud at E11.5–E12.5 (see Fig. 3). As treatment with 2.5 nM RA did not induce RARE-lacZ in the tailbud, this level of RA is likely degraded by Cyp26a1 (known to be expressed in the tailbud), suggesting that it is not a supraphysiological level of RA. These results demonstrate that RARE-lacZ can detect low levels of RA in the caudal somites and tailbud when provided in culture, but that endogenous RA is not normally present in these tissues.

FIG. 3.

RA treatment of embryonic tails validates RARE-lacZ as a sensitive RA reporter. Tails from E10.5–E12.5 wild-type embryos carrying RARE-lacZ were cultured for 18 h in the absence of RA (control) or presence of physiological doses of RA (2.5, 10, 25, or 100 nM), then stained for RARE-lacZ expression to detect RA activity. Results similar to those shown here were observed in several independent experiments; E10.5: control n = 5, 2.5 nM n = 4, 10 nM n = 2, 25 nM n = 4, 100 nM n = 1; E11.5: control n = 4, 2.5 nM n = 4, 10 nM n = 2, 25 nM n = 2, 100 nM n = 3; E12.5: control n = 4, 2.5 nM n = 3, 10 nM n = 3, 25 nM n = 6, 100 nM n = 3.

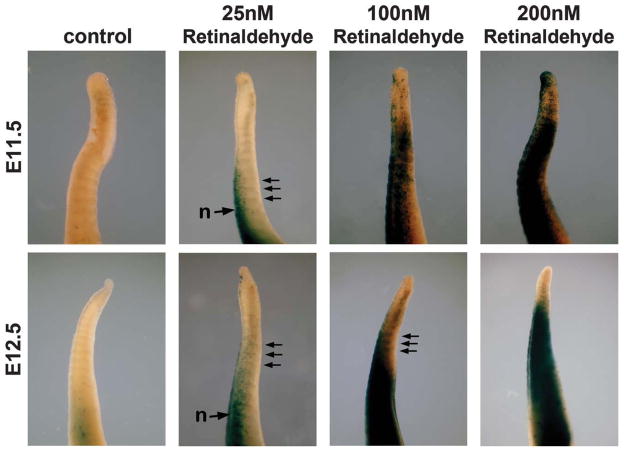

To examine why caudal somites and tailbud do not exhibit RA activity despite expressing Raldh2, we cultured tails from E11.5–E12.5 wild-type embryos carrying RARE-lacZ in the presence of retinaldehyde, the Raldh2 substrate needed to generate RA (Duester, 2008). In comparison with untreated control tails which have no RA activity in the tailbud and either little or no RA activity in caudal somites, tails treated with 25 nM retinaldehyde exhibited robust induction of RARE-lacZ in caudal neural tube and thin stripes of expression were observed in somites (see Fig. 4). Treatment with 100 nM retinaldehyde resulted in more robust induction of RARE-lacZ expression in the caudal somites, but some stripes were apparent indicating that in some cases the whole somite was not stained); treatment with 200 nM retinaldehyde induced more widespread expression of RARE-lacZ with detection in both the caudal somites at E11.5–E12.5 and in tailbud at E11.5 (see Fig. 4). The thin stripes of RARE-lacZ expression observed in somites of cultured E11.5–E12.5 tails treated with 25–100 nM retinaldehyde somewhat resemble those observed in tails from E11.5–E12.5 embryos stained immediately (Fig. 1h,k), but they are not as clear possibly due to the inability of cultured embryonic tails to fully recapitulate normal development. These studies demonstrate that functional Raldh2 enzyme is present in the tailbud and caudal somites from E11.5–E12.5, but that RA is not normally synthesized because the substrate retinaldehyde is not being generated in those tissues.

FIG. 4.

Retinaldehyde treatment of embryonic tails stimulates RA activity. Tails from E11.5–E12.5 wild-type embryos carrying RARE-lacZ were cultured for 18 h in the absence of retinaldehyde (control) or presence of retinaldehyde (25, 100, or 200 nM), then stained for RARE-lacZ expression to detect RA activity. Arrows point out thin stripes of RARE-lacZ expression in somites; n, neural tube. Results similar to those shown here were observed in several independent experiments; E11.5: control n = 4, 25 nM n = 4, 100 nM n = 2, 200 nM n = 3; E12.5: control n = 4, 25 nM n = 4, 100 nM n = 3, 200 nM n = 2.

In summary, our observations have demonstrated that Raldh2 and RA signaling are unnecessary for termination of body axis extension in the mouse. First, our genetic loss-of-function studies have shown that Raldh2 is not required for the termination process. Although Raldh2−/− embryos were administered a small dose of RA from E6.75–E9.25 to prevent lethality, this RA treatment is unlikely to have played a role in termination of body axis extension as RA treatment ended 4 days before this event which occurs at E13.5, and this RA treatment does not induce RARE-lacZ in the tailbud at E8.5–E9.5 (Zhao et al., 2009). Second, our metabolic studies have shown that from E10.5–E12.5 RA is not normally generated in the caudal somites and tailbud due to an absence (or near absence) of retinaldehyde synthesis. Very low metabolism of retinol to retinaldehyde and retinaldehyde to RA may exist in the caudal somites at E11.5–E12.5 as we observe very thin stripes of RARE-lacZ expression in the caudal-most somites. However, this very low level of RA detection does not require Raldh2 and it does not generate RA activity in the tailbud itself where RA generated by Raldh2 has been postulated to function in termination of body axis extension (Tenin et al., 2010). Expression of Cyp26a1 in the tailbud at E8.5–E9.5 has been shown to be necessary for degradation of RA actively secreted by caudal somites at those stages to prevent teratogenic effects of RA signaling on caudal trunk development (Abu-Abed et al., 2001; Sakai et al., 2001); caudal defects may be associated with reduced Fgf8 expression in the tailbud of Cyp26a1−/− embryos (Abu-Abed et al., 2003). However, our results indicate that Cyp26a1 expression previously observed in the tailbud at 10.5 (high level) or E11.5 (very low level) (MacLean et al., 2001) is unnecessary for RA degradation as caudal RA synthesis has decreased to a very low level at that stage. Together with our results, we suggest that Cyp26a1 tailbud expression may persist for some time beyond when it is needed for RA degradation, but it is clearly very much reduced by E11.5 consistent with our hypothesis that RA is not required for termination of body axis extension at approximately E13.5.

Our RA treatment studies have shown that RARE-lacZ is competent to detect low physiological RA levels in the tailbud if they exist, but no such RA activity was observed. This finding agrees with studies by others showing a lack of RA activity in mouse tailbuds cultured as explants on RA-reporter cells (Tenin et al., 2010). Thus, other mechanisms need to be investigated to determine how the caudal progenitor zone ceases to extend the body axis at a particular point in development. In particular, we demonstrate that Raldh2 is not required for down-regulation of caudal Fgf8 expression observed at E10.5–E11.5, indicating that factors other than RA are responsible. Taken together with previous studies (Sirbu and Duester, 2006), the role of RA in repressing caudal Fgf8 expression in mouse is limited to stages before E9.5. Our studies have also revealed that caution must be exercised when assigning the properties of RA synthesis and RA signaling on tissues expressing Raldh2. We have shown for the first time that a tissue can express Raldh2 but still not generate RA synthesis or RA signaling presumably due to insufficient expression of enzymes that metabolize retinol to retinaldehyde.

METHODS

Generation of Raldh2 Null Mutant Mouse Embryos

Generation of Raldh2 null embryos carrying the RARE-lacZ reporter transgene were described previously (Mic et al., 2002). Following mating, noon on the day of vaginal plug detection was considered embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). The methods for rescue of Raldh2−/− lethality by dietary RA treatment were described previously (Zhao et al., 2010). Briefly, a 50 mg/ml stock of all-trans-RA (Sigma) in 100% ethanol was mixed with corn oil to obtain a 5 mg/ml RA solution, which was then mixed thoroughly with ground mouse chow to yield a final diet containing 0.1 mg RA/g mouse chow. RA-supplemented food was provided to pregnant mice from E6.75 to E9.25 and was replaced every 12 h to ensure activity; at E9.25 mice were returned to normal mouse chow until collection of embryos at E9.5–E13.5. This low dose of RA provides embryos a physiological amount of RA (Mic et al., 2003) and the administered RA is cleared within 12–24 h after treatment ends (Mic et al., 2002), thus allowing analysis of later-stage embryos that are RA-deficient. Embryos were genotyped by PCR analysis of yolk sac DNA. All mouse studies conformed to the regulatory standards adopted by the Animal Research Committee at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute.

Culture of Embryonic Tissues and Retinoid Treatment

Tails were dissected from E10.5–E13.5 wild-type embryos (carrying the RARE-lacZ RA-reporter trans-gene) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in Millicell culture plate inserts (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Tissues were cultured for 18 h in retinoid-free DMEM/F-12 culture media (Gibco-Life Technologies, NY) containing vehicle only (control) or various concentrations of either all-trans-retinoic acid or all-trans-retinaldehyde (Sigma Chemical) dissolved in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide. After 18 h, tissues were washed twice in PBS then processed to examine RA activity (see below).

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed on E9.5–E13.5 mouse embryos or isolated embryonic tails using digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobes as described previously (Wilkinson and Nieto, 1993).

Detection of RA Activity

The RARE-lacZ RA-reporter transgene, which places lacZ (encoding β-galactosidase) under the control of a retinoic acid response element (RARE), was used for in situ detection of RA activity in embryonic tissues; β-Galactosidase activity was detected by fixation with glutaraldehyde followed by staining with X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside) for 24 h at 37°C as described (Rossant et al., 1991).

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: GM062848 (to G.D.).

The authors thank J. Rossant for RARE-lacZ mice, plus G. Martin (Fgf8) and Y. Saga (Mesp2) for mouse cDNAs used to prepare in situ hybridization probes.

Abbreviations

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- RA

retinoic acid

- RARE

retinoic acid response element

LITERATURE CITED

- Abu-Abed S, Dollé P, Metzger D, Beckett B, Chambon P, Petkovich M. The retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme. CYP26A1, is essential for normal hindbrain patterning, vertebral identity, and development of posterior structures. Genes Dev. 2001;15:226–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.855001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Abed S, Dollé P, Metzger D, Wood C, MacLean G, Chambon P, Petkovich M. Developing with lethal RA levels: Genetic ablation of Rarg can restore the viability of mice lacking Cyp26a1. Development. 2003;130:1449–1459. doi: 10.1242/dev.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brade T, Kumar S, Cunningham TJ, Chatzi C, Zhao X, Cavallero S, Li P, Sucov HM, Ruiz-Lozano P, Duester G. Retinoic acid stimulates myocardial expansion by induction of hepatic erythropoietin which activates epicardial Igf2. Development. 2011;138:139–148. doi: 10.1242/dev.054239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambray N, Wilson V. Axial progenitors with extensive potency are localized to the mouse chordoneural hinge. Development. 2002;129:4855–4866. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Corral RD, Olivera-Martinez I, Goriely A, Gale E, Maden M, Storey K. Opposing FGF and retinoid pathways control ventral neural pattern, neuronal differentiation, and segmentation during body axis extension. Neuron. 2003;40:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequeant ML, Pourquie O. Segmental patterning of the vertebrate embryonic axis. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:370–382. doi: 10.1038/nrg2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C, Ozbudak EM, Wunderlich J, Baumann D, Lewis J, Pourquie O. Control of segment number in vertebrate embryos. Nature. 2008;454:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature07020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton C, Maden M. Endogenous distribution of retinoids during normal development and teratogenesis in the mouse embryo. Dev Dyn. 1995;202:312–323. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iulianella A, Beckett B, Petkovich M, Lohnes D. A molecular basis for retinoic acid-induced axial truncation. Dev Biol. 1999;205:33–48. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel M, Gruss P. Homeotic transformations of murine vertebrae and concomitant alteration of Hox codes induced by retinoic acid. Cell. 1991;67:89–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90574-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Chatzi C, Brade T, Cunningham TJ, Zhao X, Duester G. Sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation is regulated by Cyp26b1 independent of retinoic acid signaling. Nat Commun. 2011;2:151. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean G, Abu-Abed S, Dollé P, Tahayato A, Chambon P, Petkovich M. Cloning of a novel retinoic-acid metabolizing cytochrome P450. Cyp26B1, and comparative expression analysis with Cyp26A1 during early murine development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mic FA, Haselbeck RJ, Cuenca AE, Duester G. Novel retinoic acid generating activities in the neural tube and heart identified by conditional rescue of Raldh2 null mutant mice. Development. 2002;129:2271–2282. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mic FA, Molotkov A, Benbrook DM, Duester G. Retinoid activation of retinoic acid receptor but not retinoid X receptor is sufficient to rescue lethal defect in retinoic acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7135–7140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231422100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M, Takahashi Y, Endo M, Saga Y. The Mesp2 transcription factor establishes segmental borders by suppressing Notch activity. Nature. 2005;435:354–359. doi: 10.1038/nature03591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, Subbarayan V, Dollé P, Chambon P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for early mouse post-implantation development. Nature Genet. 1999;21:444–448. doi: 10.1038/7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MK, Allen SP, Wright GM, Raynaud A, Hanken J. Somite number and vertebrate evolution. Development. 1998;125:151–160. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J, Zirngibl R, Cado D, Shago M, Giguère V. Expression of a retinoic acid response element-hsplacZ transgene defines specific domains of transcriptional activity during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1333–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Meno C, Fujii H, Nishino J, Shiratori H, Saijoh Y, Rossant J, Hamada H. The retinoic acid-inactivating enzyme CYP26 is essential for establishing an uneven distribution of retinoic acid along the anterio-posterior axis within the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:213–225. doi: 10.1101/gad.851501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbu IO, Duester G. Retinoic acid signaling in node ectoderm and posterior neural plate directs left-right patterning of somitic mesoderm. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:271–277. doi: 10.1038/ncb1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenin G, Wright D, Ferjentsik Z, Bone R, McGrew MJ, Maroto M. The chick somitogenesis oscillator is arrested before all paraxial mesoderm is segmented into somites. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J, Llamas JG, Fraulob V, Niederreither K, Chambon P, Dollé P. Retinoic acid controls the bilateral symmetry of somite formation in the mouse embryo. Science. 2005;308:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1108363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermot J, Pourquié O. Retinoic acid coordinates somitogenesis and left-right patterning in vertebrate embryos. Nature. 2005;435:215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl MB, Deng C, Lewandoski M, Pourquie O. FGF signaling acts upstream of the NOTCH and WNT signaling pathways to control segmentation clock oscillations in mouse somitogenesis. Development. 2007;134:4033–4041. doi: 10.1242/dev.009167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JA, Guo YD, Baetz K, Beckett-Jones B, Bonasoro J, Hsu KE, Dilworth FJ, Jones G, Petkovich M. Identification of the retinoic acid-inducible all-trans-retinoic acid 4-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29922–29927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Brade T, Cunningham TJ, Duester G. Retinoic acid controls expression of tissue remodeling genes Hmgn1 and Fgf18 at the digit-interdigit junction. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:665–671. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sirbu IO, Mic FA, Molotkova N, Molotkov A, Kumar S, Duester G. Retinoic acid promotes limb induction through effects on body axis extension but is unnecessary for limb patterning. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]