Abstract

Identification of chromosomal markers for rapid detection of Bacillus anthracis is difficult because significant chromosomal homology exists among B. anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis. We evaluated the bacterial gyrA gene as a potential chromosomal marker for B. anthracis. A real-time PCR assay was developed for the detection of B. anthracis. After analysis of the unique nucleotide sequence of the B. anthracis gyrA gene, a fluorescent 3′ minor groove binding probe was tested with 171 organisms from 29 genera of bacteria, including 102 Bacillus strains. The assay was found to be specific for all 43 strains of B. anthracis tested. In addition, a test panel of 105 samples was analyzed to evaluate the potential diagnostic capability of the assay. The assay showed 100% specificity, demonstrating the usefulness of the gyrA gene as a specific chromosomal marker for B. anthracis.

Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis are members of the B. cereus group of bacilli. The phylogenetic and taxonomic relationships among these species are debatable. DNA-DNA hybridization studies, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, genome sizing, and genome mapping have revealed a large degree of homology among species in this group (9-12, 24, 25, 27). There is so little difference among members of this group that some investigators have suggested that all of these organisms should be classified as B. cereus (25, 27). The differences that do exist among B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis are due largely to the presence of plasmids (4, 6, 20, 39, 42, 50, 57). However, plasmids may be lost, making it difficult to differentiate rapidly among species.

Traditionally, B. anthracis has been distinguished from other members of the B. cereus group by time-consuming techniques such as colony morphology, penicillin susceptibility, gamma phage susceptibility, lack of hemolysis, and motility (35). These methods are giving way to more rapid and quantifiable nucleic acid-based assays, such as real-time PCR (5, 31, 36, 44). The primary markers used in nucleic acid-based assays to identify B. anthracis are plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 (5, 7, 48). These plasmids are found in virulent strains of B. anthracis and carry genes that produce the toxins and the capsule, respectively. A recent study by Pannucci et al. showed a high degree of sequence conservation between plasmid pXO1 and the chromosome of some members of the B. cereus group, with several strains showing 80 to 98% homology (43). Plasmids of the B. cereus group vary widely in size and number, and transfer among members of this group has been documented (20, 47, 50). Through conjugation, pXO1 and pXO2 have been transferred into B. cereus (21, 43). Clearly, for DNA-based diagnostic methods to conclusively identify B. anthracis, a chromosomal target is needed in conjunction with pXO1 and pXO2 analysis.

Suitable chromosomal targets have been elusive for this group of organisms. The chromosomal target most commonly used to identify bacteria is the rRNA operon, which contains the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes as well as an intergenic spacer region (ISR) (1, 13, 19, 22, 32, 33, 51, 56). Unfortunately, there is no sequence difference between the 16S rRNA gene in B. anthracis and the 16S rRNA gene in some strains of B. cereus (3). The 23S rRNA gene also has shown very few sequence differences among the members of this group (2). The 16S-23S ribosomal ISR has been used with denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) to differentiate among these species (26). However, due to the nature of 16S-23S ISR DNA sequence variations, it may not be possible to use this area of the bacterial chromosome to differentiate among these species by real-time PCR (8). Another gene used for bacterial identification, the rpoB gene (16, 17, 40, 49), has shown some promise. An rpoB gene fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay was used with real-time PCR to detect B. anthracis; in that study, a total of 319 bacilli were analyzed, and only 1 B. cereus strain cross-reacted (44). Several other areas of the B. anthracis chromosome have been investigated for identification purposes. The vrrA, vrrB, vrrC, GC3, and Ba813 regions have been used as chromosomal markers for genotyping but have limited specificity (29, 46). SG-850 is another chromosomal marker, but its analysis requires digestion with AluI following PCR (14).

We chose the DNA replication gene gyrA as a potential target for real-time PCR B. anthracis identification. The gyrA gene codes for two of the four subunits of the bacterial DNA gyrase enzyme. The gyrase enzyme introduces negative supercoils into DNA in an ATP-dependent reaction (37). gyrA is characterized by areas of high conservation and areas of variability, making it suitable for bacterial identification (55). We analyzed the gyrA genes from B. anthracis and B. cereus by DHPLC and DNA sequencing and then developed a 3′ Taqman minor groove binding (MGB) probe.

In this study, we evaluated the ability of the 3′ Taqman MGB probe to differentiate among a number of Bacillus species. Taqman MGB probes form extremely stable complexes when bound to target DNA and, compared to traditional Taqman probes, have higher melting temperatures (30). These characteristics make Taqman MGB probes useful for analyzing single-base-pair mismatches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth and extraction.

The Bacillus strains analyzed in this study were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.), clinics, or entries from previous U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (Fort Detrick, Frederick, Md.) collections. Either Bactozol kits (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) or QIAamp DNA minikits (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) were used to extract DNA. Bactozol kits were used in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. QIAamp kits were used as follows. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 180 μl of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (GibcoBRL, Rockville, Md.). Twenty microliters of proteinase K and 200 μl of AL buffer (Qiagen) were added and mixed by vortexing. The mixture was incubated for 60 min at 55°C to lyse the cells. After incubation, 210 μl of 100% ethanol was added to the sample. The mixture was transferred to a QIAamp spin column and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 2 min. Next, 500 μl of AW1 buffer (Qiagen) was added to the column, and the sample was centrifuged for 2 min at 6,000 × g. Following this centrifugation step, 500 μl of AW2 buffer (Qiagen) was added to the column, and the sample was centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 2 min. Finally, 100 μl of AE buffer (Qiagen) preheated to 70°C was applied to the column, and the sample was centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 1 min to elute the DNA. The DNA concentration was determined by measuring the absorptivity of each sample at 260 nm with a DU series 500 spectrometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.).

Analysis of the 5′ end of the gyrA gene to identify organisms for assay development.

DHPLC was used to screen the 5′ end of the gyrA gene in 8 strains of B. anthracis, 33 strains of B. cereus, and 10 strains of B. thuringiensis to identify candidate strains for sequencing. B. anthracis strain Sterne was used as the reference organism.

DHPLC of the 5′ end of the gyrA gene was performed with primers GYRAF1 (5′-ATG TCA GAC AAT CAA CAA CAA GC-3′) and GYRAR2 (5′-ACA TTC TTG CTT CTG TAT AAC GC-3′). Each strain and the reference organism were amplified in 100-μl reaction mixtures containing 1.0 μM each primer, 40 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer II (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 5.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems), and 8.0 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 in molecular biology-grade water. Cycling conditions were 10 min of preincubation at 95°C to activate the AmpliTaq Gold; 35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and a 10-min 72°C final extension. All standard PCRs were performed with an MJ Research PTC-100 thermocycler.

The resulting 364-bp product was quantified with a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic analytical gradient as follows: 0.0 min, 47.0% buffer A (0.1 M triethylammonium acetate [pH 7.0], 0.025% acetonitrile), 53.0% buffer B (0.1 M triethylammonium acetate [pH 7.0], 25% acetonitrile); 0.5 min, 42.0% A, 58.0% B; 5.0 min, 33.0% A, 67.0% B; 5.1 min, 0.0% A, 100.0% B; 5.7 min, 47.0% A, 53.0% B; and 6.6 min, 47.0% A, 53.0% B. The flow rate was 0.9 ml/min, and the temperature was 50.0°C. Hybridization reaction mixtures (200 μl) contained 10 mM EDTA and equimolar amounts of driver (B. anthracis Sterne PCR product) and experimental Bacillus PCR product in molecular biology-grade water. Hybridization conditions were a 4-min preparation at 95°C, followed by a period of cooling at 25°C over 45 min at −1.5%C/min.

Mutation analysis was performed with an analytical gradient as follows: 0.0 min, 49.0% A, 51.0% B; 0.5 min, 44.0% A, 56.0% B; 5.0 min, 35.0% A, 65.0% B; 5.1 min, 0.0% A, 100.0% B; 5.7 min, 49.0% A, 51.0% B; and 6.6 min, 49.0% A, 51.0% B. The flow rate was 0.9 ml/min, and the temperature was 59.5°C.

Sequencing of the gyrA gene.

The gyrA genes in three strains of B. anthracis and two strains of B. cereus were sequenced. Primers GYRAF1 and GYRAR3 (5′-TAT TAC AAG TCT TCA GAC CTT TAC CAC-3′) were designed to amplify most of the gyrA gene. The PCR conditions for this primer set were 10 min of preincubation at 95°C; 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C; 15 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and a 10-min 72°C final extension.

PCR products were purified with QIAQuick spin columns (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were sequenced with the following primers: GYRAF1 (5′-ATG TCA GAC AAT CAA CAA CAA GC-3′), GYRAF480 (5′-ATT ACC AGC GCG TTT TCC TAA C-3′), GYRAF547 (5′-AAT ATT CCG CCG CAT CAA CT-3′), GYRAF1009 (5′-TCT CTT GTA AAT GGA GAG CCG C-3′), GYRAF1153 (5′-CGA ATT GCC TTA GAC CAT TTG G-3′), GYRAF1440 (5′-CAA TGA TAA GAG ACG CAC GGA-3′), GYRAF1571 (5′-CGT ACA AAA CAC AGA ACC GTG G-3′), GYRAF1 (5′-ATG TCA GAC AAT CAA CAA CAA GC-3′), GYRAR3 (5′-ACA TTC TTG CTT CTG TAT AAC GC-3′), GYRAR474 (5′-ATT GGC TCC CTT TCA GAA CCA-3′), GYRAR503R (5′-GCG GCT CTC CAT TTA CAA GAG A-3′), GYRAR1898 (5′-TTC GCA AAT GAT GAA AGC GG-3′), and GYRAR2042 (5′-GAA CGC ACA TCT TGC TCG TTA A-3′). Sequencing reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 2.5 μM primer, 45 ng of PCR product, and 8 μl of Big Dye (Applied Biosystems) in molecular biology-grade water. The sequence cycling conditions were 30 s of preincubation at 85°C; 25 cycles of 10 s at 96°C, 5 s at 50°C, and 4 min at 60°C; and a 10-min 60°C final extension. The sequencing reaction mixtures were purified with CentriSep columns in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, N.J.).

Primer and probe design.

Multiple-sequence alignment with DNASTAR software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) of the gyrA genes from the sequenced B. anthracis and B. cereus strains revealed genes with six silent base-pair changes at bases at positions 656, 792, 1065, 1668, 1692, and 1926 (Table 1). Potential primers and probes were generated with Primer Express software, version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). BLASTN searches were performed for all primers and probes to eliminate those which might cross-react with other known bacterial DNAs. Primer sets were further analyzed for palindromes as well as hairpin and dimer formation with NetPrimer software (http://www.microarraysoftware.com/netprimer/netprlaunch/netprlaunch.html).

TABLE 1.

gyrA nucleotide differences between B. anthracis and B. cereus strains BACI177 and BACI180a

| Codon change (B. anthracis → B. cereus) | Base position | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|

| TTT → TTC | 656 | Phe → Phe |

| TTA → CTA | 792 | Leu → Leu |

| TTG → CTG | 1065 | Leu → Leu |

| GAC → GAT | 1668 | Asp → Asp |

| AAA → AAG | 1692 | Lys → Lys |

| ATC → ATT | 1926 | Ile → Ile |

Both strains of B. cereus had all of these codon changes.

Real-time PCR amplification.

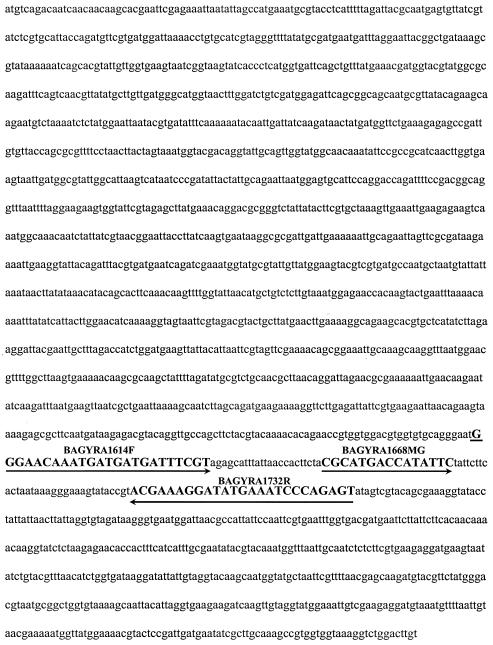

PCR was performed with a Ruggedized advanced pathogen identification device (R.A.P.I.D.) (Idaho Technology, Salt Lake City, Utah). Real time PCR reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 0.5 μM each primer (BAGYRA1614F [5′-GGG AAC AAA TGA TGA TGA TTT CGT-3′, sense] and BAGYRA1732R [5′-ACT CTG GGA TTT CAT ATC CTT TCG T-3′, antisense]), 0.375 μM probe (BAGYRA1668MGB [6′FAM-CGC ATG ACC ATA TTC-MGBNFQ-3′]) (Fig. 1), 2 μl of 10× PCR buffer containing 50 mM MgCl2 (Idaho Technology), 2 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Idaho Technology), and 0.8 U of Platinum Taq. Cycling conditions were preincubation for 120 s at 94°C to activate the Platinum Taq, 45 cycles of 20 s at 94°C and 20 s at 67°C, and a 60-s 40°C final cooling step. Positive results were determined with R.A.P.I.D. detector software (version 2.0.7).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide positions of primers BAGYRA1614F and BAGYRA1732R and probe BAGYRA1668MGB.

Specificity and sensitivity tests.

Sensitivity was determined by analyzing in triplicate serial 10-fold dilutions of genomic DNA from two strains of B. anthracis (Ames and dANR) starting at 1 ng and ending at 1 fg. Specificity was tested by using 100 pg of genomic DNA from 43 strains of B. anthracis, 36 strains of B. cereus, and 12 strains of B. thuringiensis as well as a cross-reactivity panel consisting of 59 different species (Table 2). A panel of 105 masked samples (samples whose identity was unknown) was tested to evaluate the potential diagnostic capability of the assay (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

List of organisms used in this study to determine the specificity of probe BAGYRA1668MGB

| Organism | No. of strains tested |

|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 |

| Alcaligenes xylosoxidans | 1 |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 1 |

| Bacillus anthracis | 43 |

| Bacillus cereus | 36 |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | 13 |

| Bacillus coagulans | 1 |

| Bacillus licheniformis | 1 |

| Bacillus macerans | 1 |

| Bacillus megaterium | 1 |

| Bacillus polymyxa | 1 |

| Bacillus popilliae | 1 |

| Bacillus sphaericus | 1 |

| Bacillus stearothermophilus | 1 |

| Bacillus subtilis subsp. niger | 2 |

| Bacteroides distasonis | 1 |

| Brucella melitensis | 1 |

| Budvicia aquatica | 1 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | 1 |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | 1 |

| Clostridium botulinum | 2 |

| Clostridium sordellii | 1 |

| Clostridium perfringens | 3 |

| Clostridium sporogenes | 1 |

| Comamonas acidovorans | 1 |

| Comamonas terrigena | 1 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 |

| Enterobacter agglomerans | 1 |

| Enterococcus durans | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 |

| Francisella tularensis | 6 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 1 |

| Neisseria lactamica | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 |

| Proteus vulgaris | 1 |

| Providencia stuartii | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 |

| Ralstonia pickettii | 1 |

| Salmonella choleraesuis | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 |

| Serratia odorifera | 1 |

| Shigella flexneri | 1 |

| Shigella sonnei | 1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 1 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 |

| Streptococcus sp. (group B) | 1 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 2 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 3 |

| Yersinia kristensenii | 2 |

| Yersinia ruckeri | 2 |

| Yersinia pestis | 6 |

| Yersinia frederiksenii | 1 |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | 1 |

RESULTS

DHPLC analysis.

To determine whether the gyrA gene was a suitable target for distinguishing B. anthracis from the other members of the B. cereus group, we examined the first 364 bp of the gyrA gene by DHPLC. Two strains of B. cereus had peak profiles identical to those of the eight strains of B. anthracis tested, indicating similar sequences. Sequencing of the gyrA gene in these strains and three strains of B. anthracis revealed genes in B. cereus with six nucleotide differences resulting in silent codon substitutions (Table 1). Further DHPLC analysis showed that two of these nucleotide differences were specific for B. anthracis (GenBank accession no. AY291534 and AY291535).

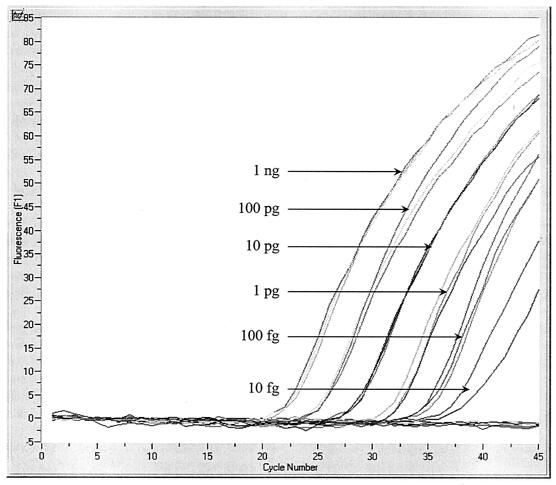

Level of detection.

Tenfold serial dilutions (from 1 ng to 1 fg) of two strains of B. anthracis were tested in triplicate to determine the lowest concentration of template DNA that could be detected 100% of the time. The level of detection results indicate that the BAGYRA primer-probe set was able to detect 100 fg of genomic DNA (Fig. 2). Based on genome size and GC content, the detection limit was 20 to 30 genome copies per PCR.

FIG. 2.

Results of triplicate analysis of B. anthracis Ames 10-fold serial dilutions ranging from 1 ng to 1 fg of template DNA. The average cycle threshold values were as follows: 1 ng, 22.25; 100 pg, 25.16; 10 pg, 28.29; 1 pg, 31.77; and 100 fg, 35.26. The 10-fg dilution was not detected consistently. The 1-fg dilution and the no-template control were not detected.

Specificity testing.

BLASTN results indicated that primers BAGYRA1614F and BAGYRA1732R and probe BAGYRA1668MGB were potentially specific for B. anthracis. Previous DHPLC work in our laboratory showed that there are at least two different alleles of the gyrA gene in B. anthracis (26). To ensure that the BAGYRA primer-probe set would amplify all strains of B. anthracis, we tested it with 43 strains of B. anthracis. Given the high degree of homology of the B. cereus group genome, we tested the BAGYRA primer-probe set with 36 strains of B. cereus and 13 strains of B. thuringiensis. All strains of B. anthracis were detected, and no strains of B. cereus or B. thuringiensis were detected. To determine whether the BAGYRA primer-probe set would detect other species of bacteria, we tested a panel of DNAs from 171 organisms of 29 genera (Table 2). No organisms from this panel were detected (data not shown).

Masked-sample analysis.

A panel of 105 masked samples was tested to evaluate the diagnostic capability of the BAGYRA primer-probe set (Table 2). Of the 15 B. anthracis samples in the panel, all were identified correctly. There were no false-positive results.

DISCUSSION

B. cereus and B. thuringiensis are the two closest relatives of B. anthracis (25, 27, 52). A recent study analyzing the allozyme patterns of 13 enzyme loci showed that B. anthracis is indistinguishable genetically from some strains of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis (25). The primary markers used to differentiate B. anthracis from other members of the B. cereus group are plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 (5, 7, 48). Conjugation studies have shown that pXO1 and pXO2 can be transferred from B. anthracis to B. cereus (21). Plasmid transfer between Bacillus species can obscure the identification process. Moreover, the identification process can be complicated further because some strains of B. anthracis carry either pXO1 or pXO2 while other strains lack both plasmids. Plasmid-cured strains of B. anthracis have been isolated (53). In addition to these confounding problems, site-directed mutagenesis at crucial locations on either of these plasmids could make pXO1 or pXO2 assays ineffective.

Both pXO1 and pXO2 are large plasmids. pXO1 is 174 kb and carries the pag, lef, and cya toxin genes (28). pXO2 is 95 kb and carries the capA, capB, and capC genes (28). These genes are essential for a strain of B. anthracis to be virulent and are the most commonly targeted for plasmid-based assays (18, 45, 53). With modern molecular biological techniques, these plasmids could be removed from the organism and manipulated by site-directed mutagenesis to produce genes that code for the same protein but with a different nucleotide sequence. In such a scenario, a nucleic acid-based assay targeting these genes would be useless. Unquestionably, a chromosomal marker is needed to identify B. anthracis without ambiguity.

Several chromosomal Bacillus markers have been identified, and none is specific to B. anthracis. We investigated the gyrA gene to assess its potential use as a B. anthracis-specific chromosomal marker. Due to the highly conserved nature of B. cereus group genomes, we decided to screen several Bacillus organisms by DHPLC to determine whether the gyrA gene was a suitable target for assay development. Because the amino acids at the amino terminus of gyrase peptides are more conserved than the amino acids at the carboxyl terminus (54), we screened the 5′ end of the gyrA gene by DHPLC to identify organisms suitable for assay development. Our DHPLC and sequencing data revealed several strains of B. cereus with gyrase A peptides similar to those of B. anthracis strains. These strains had gyrA genes that differed from those of B. anthracis by six nucleotides, but the genes coded for the same amino acid sequence (Table 1).

Single nucleotide differences can be detected by a number of techniques. Recently, MGB proteins conjugated to DNA probes were used for this purpose (15). Taqman MGB probes form extremely stable complexes when bound to their targets, allowing for the development of probes that are much smaller than traditional Taqman probes and making them useful for analyzing A-T-rich sequences. We exploited this characteristic of Taqman MGB probes to analyze the nucleotide at position 1668 in the gyrA gene of B. anthracis. The B. anthracis genome is A-T rich (66.5%) (38), and the area surrounding the position 1668 C → T transversion has a slightly richer A-T content—70.0%. Initially, we tried to design a traditional Taqman probe for the position 1668 C → T transversion and found that a Taqman probe with an annealing temperature similar to that of BAGYRA1668MGB was 35 bp long. While some Taqman probes have been used to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (23, 34, 41), it is unlikely that a Taqman probe in excess of 30 bp will efficiently detect such a subtle DNA variation. A recent study showed that Taqman MGB probes had the highest melting temperatures when there was a single-base-pair mismatch in the MGB region of the target DNA (30). The mutation analyzed in this study was 2 nucleotides outside of this region. Taqman MGB probes can be designed to lower the annealing temperature of this assay to increase its sensitivity. We were able to reliably detect 100 fg of template DNA with this assay (Fig. 1), a value which translates to 20 to 30 genome copies. It may be possible to detect two or three genome copies or possibly one genome copy with a probe that has a single-base-pair mismatch in the MGB region.

Clinically isolated B. anthracis may be associated with either commensal or pathogenic bacteria. To determine whether the BAGYRA1668 MGB probe would cross-react with other bacteria, we tested it with 43 strains of B. anthracis, 36 strains of B. cereus, and 13 strains of B. thuringiensis. In addition, we tested another group of 171 organisms from a variety of genera and species (Table 2). To demonstrate the potential diagnostic utility of this assay, we tested a panel of 105 masked samples. All B. anthracis samples in the panel tested positive, and there were no false-positive results, indicating that the gyrA gene is a valuable B. anthracis target for a specific chromosomal assay. Although the results obtained with the 43 strains of B. anthracis were positive, further testing is needed because of the possibility of a false-negative result occurring from a different gyrA allele in B. anthracis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afseth, G., Y. Y. Mo, and L. P. Mallavia. 1995. Characterization of the 23S and 5S rRNA genes of Coxiella burnetii and identification of an intervening sequence within the 23S rRNA gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:2946-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ash, C., and M. D. Collins. 1992. Comparative analysis of 23S ribosomal RNA gene sequences of Bacillus anthracis and emetic Bacillus cereus determined by PCR-direct sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 73:75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash, C., J. A. Farrow, M. Dorsch, E. Stackebrandt, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battisti, L., B. D. Green, and C. B. Thorne. 1985. Mating system for transfer of plasmids among Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Bacteriol. 162:543-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, C. A., J. R. Uhl, T. L. Hadfield, J. C. David, R. F. Meyer, T. F. Smith, and F. R. Cockerill III. 2002. Detection of Bacillus anthracis DNA by LightCycler PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2897-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernhard, K., H. Schrempf, and W. Goebel. 1978. Bacteriocin and antibiotic resistance plasmids in Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 133:897-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyer, W., P. Glockner, J. Otto, and R. Bohm. 1995. A nested PCR method for the detection of Bacillus anthracis in environmental samples collected from former tannery sites. Microbiol. Res. 150:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourque, S. N., J. R. Valero, M. C. Lavoie, and R. C. Levesque. 1995. Comparative analysis of the 16S to 23S ribosomal intergenic spacer sequences of Bacillus thuringiensis strains and subspecies and of closely related species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1623-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson, C. R., A. Gronstad, and A. B. Kolsto. 1992. Physical maps of the genomes of three Bacillus cereus strains. J. Bacteriol. 174:3750-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson, C. R., T. Johansen, and A. B. Kolsto. 1996. The chromosome map of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. canadensis HD224 is highly similar to that of the Bacillus cereus type strain ATCC 14579. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 141:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson, C. R., and A. B. Kolsto. 1993. A complete physical map of a Bacillus thuringiensis chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 175:1053-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson, C. R., and A. B. Kolsto. 1994. A small (2.4 Mb) Bacillus cereus chromosome corresponds to a conserved region of a larger (5.3 Mb) Bacillus cereus chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 13:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox, R. A., K. Kempsell, L. Fairclough, and M. J. Colston. 1991. The 16S ribosomal RNA of Mycobacterium leprae contains a unique sequence which can be used for identification by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:284-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daffonchio, D., S. Borin, G. Frova, R. Gallo, E. Mori, R. Fani, and C. Sorlini. 1999. A randomly amplified polymorphic DNA marker specific for the Bacillus cereus group is diagnostic for Bacillus anthracis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1298-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Kok, J. B., E. T. Wiegerinck, B. A. Giesendorf, and D. W. Swinkels. 2002. Rapid genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms using novel minor groove binding DNA oligonucleotides (MGB probes). Hum. Mutat. 19:554-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drancourt, M., A. Carlioz, and D. Raoult. 2001. rpoB sequence analysis of cultured Tropheryma whippelii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2425-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drancourt, M., and D. Raoult. 2002. rpoB gene sequence-based identification of Staphylococcus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1333-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fasanella, A., S. Losito, T. Trotta, R. Adone, S. Massa, F. Ciuchini, and D. Chiocco. 2001. Detection of anthrax vaccine virulence factors by polymerase chain reaction. Vaccine 19:4214-4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaydos, C. A., T. C. Quinn, and J. J. Eiden. 1992. Identification of Chlamydia pneumoniae by DNA amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:796-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez, J. M., Jr., B. J. Brown, and B. C. Carlton. 1982. Transfer of Bacillus thuringiensis plasmids coding for delta-endotoxin among strains of B. thuringiensis and B. cereus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:6951-6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green, B. D., L. Battisti, and C. B. Thorne. 1989. Involvement of Tn4430 in transfer of Bacillus anthracis plasmids mediated by Bacillus thuringiensis plasmid pXO12. J. Bacteriol. 171:104-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillot, E., and H. Leclerc. 1993. Biological specificity of bottled natural mineral waters: characterization by ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene restriction patterns. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 75:292-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampe, J., A. Wollstein, T. Lu, H. J. Frevel, M. Will, C. Manaster, and S. Schreiber. 2001. An integrated system for high throughput TaqMan based SNP genotyping. Bioinformatics 17:654-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrell, L. J., G. L. Andersen, and K. H. Wilson. 1995. Genetic variability of Bacillus anthracis and related species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1847-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helgason, E., O. A. Okstad, D. A. Caugant, H. A. Johansen, A. Fouet, M. Mock, I. Hegna, and Kolsto. 2000. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2627-2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurtle, W., E. Bode, R. S. Kaplan, J. Garrison, B. Kearney, D. Shoemaker, E. Henchal, and D. Norwood. 2003. Use of denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography to identify Bacillus anthracis by analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA interspacer region and gyrA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4758-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko, T., R. Nozaki, and K. Aizawa. 1978. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness between Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Immunol. 22:639-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaspar, R. L., and D. L. Robertson. 1987. Purification and physical analysis of Bacillus anthracis plasmids pXO1 and pXO2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 149:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keim, P., L. B. Price, A. M. Klevytska, K. L. Smith, J. M. Schupp, R. Okinaka, P. J. Jackson, and M. E. Hugh-Jones. 2000. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2928-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutyavin, I. V., I. A. Afonina, A. Mills, V. V. Gorn, E. A. Lukhtanov, E. S. Belousov, M. J. Singer, D. K. Walburger, S. G. Lokhov, A. A. Gall, R. Dempcy, M. W. Reed, R. B. Meyer, and J. Hedgpeth. 2000. 3′-Minor groove binder-DNA probes increase sequence specificity at PCR extension temperatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:655-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, M. A., G. Brightwell, D. Leslie, H. Bird, and A. Hamilton. 1999. Fluorescent detection techniques for real-time multiplex strand specific detection of Bacillus anthracis using rapid PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linton, D., F. E. Dewhirst, J. P. Clewley, R. J. Owen, A. P. Burnens, and J. Stanley. 1994. Two types of 16S rRNA gene are found in Campylobacter helveticus: analysis, applications and characterization of the intervening sequence found in some strains. Microbiology 140:847-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linton, D., A. J. Lawson, R. J. Owen, and J. Stanley. 1997. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2568-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak, K. J. 1999. Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5′ nuclease assay. Genet. Anal. 14:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logan, N. A., J. A. Carman, J. Melling, and R. C. Berkeley. 1985. Identification of Bacillus anthracis by API tests. J. Med. Microbiol. 20:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino, S. I., H. I. Cheun, M. Watarai, I. Uchida, and K. Takeshi. 2001. Detection of anthrax spores from the air by real-time PCR. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxwell, A., and M. Gellert. 1984. The DNA dependence of the ATPase activity of DNA gyrase. J. Biol. Chem. 259:14472-14480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald, W. G. 1966. Perforation and hemorrhage after gastrointestinal mucosal biopsy in a child. Gastroenterology 51:390-392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDowell, D. G., and N. H. Mann. 1991. Characterization and sequence analysis of a small plasmid from Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki strain HD1-DIPEL. Plasmid 25:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollet, C., M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 1997. rpoB sequence analysis as a novel basis for bacterial identification. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1005-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver, D. H., R. E. Thompson, C. A. Griffin, and J. R. Eshleman. 2000. Use of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and real-time polymerase chain reaction for bone marrow engraftment analysis. J. Mol. Diagn. 2:202-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ombui, J. N., J. M. Mathenge, A. M. Kimotho, J. K. Macharia, and G. Nduhiu. 1996. Frequency of antimicrobial resistance and plasmid profiles of Bacillus cereus strains isolated from milk. East Afr. Med. J. 73:380-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pannucci, J., R. T. Okinaka, R. Sabin, and C. R. Kuske. 2002. Bacillus anthracis pXO1 plasmid sequence conservation among closely related bacterial species. J. Bacteriol. 184:134-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qi, Y., G. Patra, X. Liang, L. E. Williams, S. Rose, R. J. Redkar, and V. G. DelVecchio. 2001. Utilization of the rpoB gene as a specific chromosomal marker for real-time PCR detection of Bacillus anthracis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3720-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramisse, V., G. Patra, H. Garrigue, J. L. Guesdon, and M. Mock. 1996. Identification and characterization of Bacillus anthracis by multiplex PCR analysis of sequences on plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 and chromosomal DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 145:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramisse, V., G. Patra, J. Vaissaire, and M. Mock. 1999. The Ba813 chromosomal DNA sequence effectively traces the whole Bacillus anthracis community. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:224-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy, A., L. Battisti, and C. B. Thorne. 1987. Identification of self-transmissible plasmids in four Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies. J. Bacteriol. 169:5263-5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reif, T. C., M. Johns, S. D. Pillai, and M. Carl. 1994. Identification of capsule-forming Bacillus anthracis spores with the PCR and a novel dual-probe hybridization format. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1622-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Renesto, P., K. Lorvellec-Guillon, M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 2000. rpoB gene analysis as a novel strategy for identification of spirochetes from the genera Borrelia, Treponema, and Leptospira. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2200-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruhfel, R. E., N. J. Robillard, and C. B. Thorne. 1984. Interspecies transduction of plasmids among Bacillus anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis. J. Bacteriol. 157:708-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saunders, N. A., T. G. Harrison, N. Kachwalla, and A. G. Taylor. 1988. Identification of species of the genus Legionella using a cloned rRNA gene from Legionella pneumophila. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2363-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Somerville, H. J., and M. L. Jones. 1971. Genetic relatedness within the Bacillus cereus group of bacilli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 69:ix. [PubMed]

- 53.Turnbull, P. C., R. A. Hutson, M. J. Ward, M. N. Jones, C. P. Quinn, N. J. Finnie, C. J. Duggleby, J. M. Kramer, and J. Melling. 1992. Bacillus anthracis but not always anthrax. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 72:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, J., L. M. Parsons, and K. M. Derbyshire. 2003. Unconventional conjugal DNA transfer in mycobacteria. Nat. Genet. 34:80-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, J. C. 1996. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:635-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whiley, R. A., B. Duke, J. M. Hardie, and L. M. Hall. 1995. Heterogeneity among 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacers of species within the ‘Streptococcus milleri group.' Microbiology 141:1461-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang, C. Y., J. C. Pang, S. S. Kao, and H. Y. Tsen. 2003. Enterotoxigenicity and cytotoxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis strains and development of a process for Cry1Ac production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51:100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]