Abstract

Diarrhea remains one of the main sources of morbidity and mortality in the world, and a large proportion is caused by diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. In Mongolia, the epidemiology of diarrheagenic E. coli has not been well studied. A total of 238 E. coli strains from children with sporadic diarrhea and 278 E. coli strains from healthy children were examined by PCR for 10 virulence genes: enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) eae, tir, and bfpA; enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) lt and st; enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) ipaH; enterohemorragic E. coli stx1 and stx2; and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) aggR and astA. EAEC strains without AggR were identified by the HEp-2 cell adherence test. The detection of EAEC, ETEC, EPEC, and EIEC was significantly associated with diarrhea. The incidence of EAEC (15.1%), defined by either a molecular or a phenotypic assay, was higher in the diarrheal group than any other category (0 to 6.0%). The incidence of AggR-positive EAEC in the diarrheal group was significantly higher than in the control group (8.0 versus 1.4%; P = 0.0004), while that of AggR-negative EAEC was not (7.1 versus 4.3%). Nineteen AggR-positive EAEC strains harbored other EAEC virulence genes—aggA, 2 (5.5%); aafA, 4 (11.1%); agg-3a, 5 (13.8%); aap, 8 (22.2%); aatA, 11 (30.5%); capU, 9 (25.0%); pet, 6 (16.6%); and set, 3 (8.3%)—and showed 15 genotypes. EAEC may be an important pathogen of sporadic diarrhea in Mongolian children. Genetic analysis showed the heterogeneity of EAEC but illustrated the importance of the AggR regulon (denoting typical EAEC) as a marker for virulent EAEC strains.

Diarrhea continues to be one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among infants and children in developing countries (5, 18). Five distinct classes of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) are recognized as being associated with diarrheal disease. They are enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC); diffuse adhering E. coli (DAEC) may represent a sixth category, but this has not been clearly established (18). Each class of DEC is defined on the basis of distinct virulence characteristics, and tests for these characteristics have been developed to distinguish DEC classes from each other and from nonpathogenic E. coli strains of the normal flora (15, 34). The epidemiological significance of each E. coli category in childhood diarrhea varies with the geographical area. It has become clear that there are important regional differences in the prevalences of the different categories of DEC. The incidences of diarrheal illnesses caused by the different categories of DEC were examined mainly in Latin America, Africa, southern and Southeast Asia, and the Middle East (1, 3, 25, 32, 35, 36, 45). Study of the prevalences of DEC categories and their importance in childhood diarrhea has not been carried out in Mongolia. Therefore, to define the association of various categories of E. coli with diarrhea in Mongolia, we carried out a controlled study using PCR for identification of specific virulence factors.

Among the DEC categories, EAEC appears to have been increasingly recognized as an emerging pathogen causing diarrhea in both developing and industrialized countries (20, 26, 28). Few studies have compared the presence of EAEC markers in strains isolated from children with and without diarrhea in different geographic regions (9, 11, 24). No single study of enteric EAEC, their heterogeneous natures, and the epidemiological significance of the organism is available in Mongolia. To characterize EAEC strains isolated in Mongolia, we investigated the prevalences of virulence factors and the genotypes of EAEC from children with sporadic diarrhea and without diarrhea. This is the first report of the epidemiology of DEC in Mongolia.

(This research was presented in part at the 103rd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., in May 2003 [J. Sarantuya, J. Nishi, N. Wakimoto, and K. Manago, Abstr. 103rd Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D-109, p. 221, 2003].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and strains.

A total of 238 E. coli isolates from children with sporadic diarrhea (0 to 16 years of age; mean age, 5.3 years) and 278 E. coli isolates from healthy children (0 to 16 years of age; mean age, 6.3 years) were isolated in the bacteriological laboratories of three hospitals in Ulaanbaatar City (Mother and Child Health Center, Infectious Disease Hospital, and Second Clinical Hospital) from July 2001 through September 2002. Patients were enrolled in the study if they had diarrhea characterized by frequent watery stools (>3 times/day) with or without blood or mucus. The children had not taken any antimicrobial agent in the week preceding sampling. A control group of apparently healthy children with a similar age distribution was selected from the clinic population. These children were admitted to the hospital for nondiarrheal illnesses and without a history of diarrhea and/or of taking any antimicrobial agent for at least 1 month.

Specimens were collected by means of sterile cotton applicators applied to the rectums of case patients and control subjects. The swabs were transferred directly to the surfaces of MacConkey agar plates. Organisms producing colonies after 24 or 48 h of incubation were transferred to fresh plates and onto nutrient agar. Only one stool specimen from each case patient or control subject was tested. All specimens were processed by routine microbiological and biochemical tests in the bacteriological laboratories to identify Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Vibrio spp., Aeromonas spp., and Yersinia enterocolitica, and they were also examined for Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia. All specimens in our study were negative for these bacterial and parasitic pathogens. All E. coli-like colonies from a single stool sample with identical colony morphologies and biochemical properties were assumed to be identical; if isolates were found to be identical, only one colony from that specimen was analyzed further. A total of 516 E. coli isolates from case patients and control subjects were transferred in transport medium to Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Japan, and examined further. E. coli strains were individually stored at −80°C in skim milk for routine examination.

PCR analysis.

As a template, we used DNA purified by a standard biochemical method with phenol-chloroform extraction. All strains were evaluated by PCR for identification of 10 virulence genes of distinct DEC groups: eae (46), tir, and bfpA (42) for EPEC; st and lt (40) for ETEC; ipaH (37) for EIEC; stx1 and stx2 (33) for EHEC; and astA (encoding the toxin EAST1) (46) and aggR (42) for EAEC. Each primer sequence and the conditions for PCR were obtained from the relevant references. The tir gene was amplified using primers with the following sequences: 5′-CAGCCTTCGTTCAGATCCTA-3′ (positions 1971 to 1990) and 5′-GTAGCCAGCCCCCGATGA-3′ (positions 2374 to 2391) (GenBank accession no. AF070067). As a positive control, we used standard EPEC, EIEC, ETEC, EHEC, and EAEC strains, which were kindly provided by the Osaka Prefectural Institute of Public Health, Osaka, and Kagoshima Prefectural Institute for Environmental Research and Public Health, Kagoshima, Japan. Also, the genes encoding the aggregative-adherence (AA) fimbriae (AAF/I) (aggA), AAF/II (aafA) (44), and AAF/III (agg-3a) (2); plasmid-encoded toxin (pet) (10); Shigella enterotoxin 1 (set) (44); dispersin protein (aap) (38); cap locus protien (capU) (7); and AA probe-associated protein (aatA) (22) were investigated by PCR among EAEC strains. Each primer sequence and the PCR conditions were obtained from the relevant references. The primers for the aap gene were as follows: 5′-TGAAAAAAATTAAGTTTGTTATC-3′ (forward; positions 18 to 40) and 5′-AACCCATTCGGTTAGAGC-3′ (reverse; positions 344 to 361) (GenBank accession no. Z32523). The primers for the aatA gene were as follows: 5′-ATGTTACCAGATATAAATATAG-3′ (forward; positions 2723 to 2744) and 5′-CATTTCCCCTGTATTGGAAATG-3′ (reverse; positions 3766 to 3787) (GenBank accession no. AY351860). The primers for the capU gene were as follows: 5′-ATGAATATACTATTTACGGAATC-3′ (forward; positions 1403 to 1425) and 5′-CTACAGGCACAGAAAATGCCGATG-3′ (reverse; positions 2201 to 2224) (GenBank accession no. AF134403). The assay was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (PC 707; ASTEC, Fukuoka, Japan), and the PCR products were electrophoresed in agarose gels.

HEp-2 cell adherence test.

E. coli isolates were subjected to a HEp-2 cell adherence test by the method described by Nataro et al. with slight modifications (19).

Quantitative biofilm assay.

For the assessment of biofilm formation, 200 μl of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 0.45% glucose in a 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate was inoculated with 5 μl of an overnight Luria broth culture grown at 37°C with shaking. The plate was incubated at 37°C overnight (18 h) and then the culture was visualized by staining it with 0.5% crystal violet for 5 min after washing it with water (39). The biofilm was quantified in duplicate, after the addition of 200 μl of 95% ethanol, by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader at 570 nm. EAEC 042 was used as a positive control, and E. coli HB101 was used as a negative control.

PFGE assay.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed using a CHEF-DR 3 apparatus (Nippon Bio-Rad Laboratories K.K., Tokyo, Japan) according to the instruction manual. DNA was digested by XbaI and separated on 1% agarose gels by PFGE under the following conditions: current range, 100 to 130 mA at 14°C for 20 h; initial switch time, 5.3 s, linearly increasing to a final switch time of 49.9 s; angle, 120°; field strength, 6 V/cm. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed. A lambda DNA ladder with a size range of 48.5 kb to 1 Mb (BME, Rockland, Maine) was used as a size marker.

Serogrouping.

All PCR-positive DEC isolates identified were O serogrouped by a slide agglutination test using commercially available antisera (Denkaseiken, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done by Fisher's exact test and univariate and multivariate stepwise regression analyses. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 516 E. coli strains were evaluated by PCR to detect 10 virulence genes to classify the DEC categories. EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, and EHEC were defined as strains having the respective virulence genes. The incidences of each virulence gene among E. coli isolates in the diarrheal and control groups are shown in Table 1. The incidence of each gene was significantly higher in the diarrheal group than in the control group, except for lt, stx1, and stx2. Because EAEC has been defined as comprising strains showing typical AA in a HEp-2 cell adherence test, we examined the AggR-positive strains for the adherence pattern. Nineteen of 22 AggR-positive strains in the diarrheal group and 4 of 12 AggR-positive strains in the control group showed AA and were identified as EAEC. To detect AggR-negative EAEC, we performed a HEp-2 cell adherence test of AggR-negative E. coli. Seventeen AggR-negative EAEC strains were found in the diarrheal group, and 12 were found in the control group (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Incidences of each virulence gene among E. coli isolates in diarrheal and control groups

| Virulence gene | No. of strains (%)

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrheal (n = 238) | Control (n = 278) | ||

| eae | 9 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.0009 |

| tir | 9 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.0009 |

| bfpA | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| ipaH | 8 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| lt | 7 (2.9) | 2 (0.7) | NS |

| st | 9 (3.8) | 2 (0.7) | 0.028 |

| stx1 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | NS |

| stx2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| aggR | 22 (9.2) | 12 (4.3) | 0.021 |

| astA | 52 (21.8) | 14 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

NS, not significant.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of diarrheagenic E. coli categories among E. coli strains examined

| DEC categorya | No. of strains (%)

|

P valueb | O serotypesc (no. of strains) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrheal (n = 238) | Control (n = 278) | |||

| EPEC (total) | 9 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0.0009 | |

| Typical | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.02 | O55 (1), O111 (3), NT (1) |

| Atypical | 4 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0.04 | O6 (1), O111 (1), NT (2) |

| ETEC (total) | 14 (6.0) | 3 (1.1) | 0.002 | |

| LT only | 5 (2.1) | 1 (0.3) | NS | O143 (1), O159 (1), NT (4) |

| ST only | 8 (3.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.013 | O6 (1), O78 (1), NT (7) |

| LT and ST | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | NS | O55 (1), NT (1) |

| EIEC | 8 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0.002 | O28 (1), O112 (1), O115 (1), O158 (1), NT (4) |

| EHEC | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | NS | NT (1) |

| EAEC (total) | 36 (15.1) | 16 (5.7) | 0.0006 | |

| AggR positive | 19 (8.0) | 4 (1.4) | 0.0004 | O15 (2), O126 (2), O148 (1), NT (18) |

| AggR negative | 17 (7.1) | 12 (4.3) | NS | NT (29) |

| Total | 67 (28.1) | 20 (7.2) | <0.0001 | |

LT, heat-labile toxin; ST, heat-stable toxin.

NS, not significant.

NT, nontypeable.

The incidences of DEC categories in the diarrheal and the control group are shown in Table 2. The incidence of DEC in the diarrheal group (28.1%; 67 of 238) was significantly higher than that in the control group (7.2%; 20 of 278) (P < 0.0001). The most prevalent category was EAEC, followed by ETEC, EPEC, and EIEC. EHEC was not detected in any case patient, but one strain was found in the control group. In our study, five patients had visibly bloody stools in a history of the illness. EPEC, EIEC, and EAEC were detected in each of three patients. The strains from the remaining two patients did not belong to any recognized DEC category.

All nine EPEC strains were positive for the eae and tir genes; five of them were positive for the bfpA gene in the diarrheal group. These five strains with eae, tir, and bfpA genes showed localized adherence to HEp-2 cells (typical EPEC). The incidence of ETEC in the diarrheal group was significantly higher than that in the control group. ETEC producing only ST was significantly associated with diarrheal disease; LT-only producers and those strains carrying genes for ST and LT were not associated with diarrhea in this population, though the numbers were surprisingly low. EPEC and EIEC were not detected in any subject in the control group, showing the significant association of both categories with diarrhea. EAST1 was detected in 52 (21.8%) strains in the diarrheal group (of which 9 samples were EAEC, 6 samples were ETEC, and one sample was DAEC) and 14 (5%) strains in the control group (of which 1 strain was EAEC and 1 was ETEC). We analyzed the significance of the astA gene by multiple regression analysis. The astA gene was significantly associated with the lt gene (P < 0.0001). The incidence of strains carrying both lt and astA was higher in the diarrheal group (2.5%; 6 of 238) than in the control group (0.4%; 1 of 278); however, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.053). The presence of the astA gene was significant for production of diarrhea only in EAEC strains, not in strains with other virulence genes. The incidence of strains carrying astA that did not belong to any recognized DEC category was significantly higher in the diarrheal group (21.0%; 36 of 171) than in the control group (14.6%; 2 of 258) (P < 0.0001). The incidence of AggR-positive EAEC in the diarrheal group was significantly higher than in the control group, while that of AggR-negative EAEC was not.

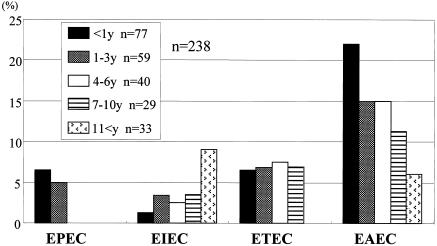

The age distribution of patients with DEC is shown in Fig. 1. EPEC strains were mainly isolated in the <3-year age group. EIEC was observed in all age groups, with an increasing trend toward the >11-year age group. EAEC, commonly seen in all age groups, tends to be isolated more often in the ≤1-year age group.

FIG. 1.

Age distribution of diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) categories in the diarrheal group. Shown is a comparison of the isolation rates of E. coli categories in the five age groups (y, years). The bars show the percentages of patients with DEC infection in the populations of the age groups.

To further characterize the identified EAEC strains, we evaluated the eight virulence genes of EAEC in addition to aggR and astA. Table 3 shows the incidences of the examined genes among the EAEC isolates. The virulence genes were mainly observed in the AggR-positive EAEC strains in the diarrheal group. The combinations of the virulence genes among EAEC strains are shown in Table 4. A variety of different combinations of the genes was observed more prevalently in the diarrheal group than in the control group. As the aatA gene sequence overlaps with the region of the conventional CVD432 (AA) probe, we considered aatA-positive strains to be AA probe positive. This probe sequence was not found in the control group. EAEC strains of the diarrheal group harboring two or more markers were observed more frequently in AA probe-positive strains (100%; 11 of 11) than in AA probe-negative strains (29.6%; 8 of 25) (P = 0.0001).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of virulence-related markers among EAEC strains

| EAEC factor | Diarrheal

|

Control

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n = 36) | AggR+ (n = 19) | AggR− (n = 17) | Total (%) (n = 16) | AggR+ (n = 4) | AggR− (n = 12) | |

| AAF/I | 2 (5.5) | 1 | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| AAF/II | 4 (11.1) | 4 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| AAF/III | 5 (13.8) | 5 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| AA (AatA) | 11 (30.5) | 11 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Aap | 8 (22.2) | 8 | 0 | 1 (6.25) | 1 | 0 |

| CapU | 9 (25.0) | 8 | 1 | 2 (12.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Pet | 6 (16.6) | 6 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| EAST1 | 12 (33.3) | 9 | 3 | 1 (6.25) | 1 | 0 |

| ShET1 | 3 (8.3) | 3 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

TABLE 4.

Combinations of virulence markers among EAEC strains

| EAEC (no. of strains) | Gene combination | No. (%) of strains |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea (36) | aggR aafA pet aap aatA astA cap set | 2 (5.5) |

| aggR agg-3a pet aap aatA astA cap set | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR aafA pet aap astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR agg-3a aap aatA astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR aafA pet astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR agg-3a aap aatA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR agg-3a pet cap | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR aatA cap astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR aggA aatA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR agg-3a aatA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR aap aatA | 2 (5.5) | |

| aggR aatA cap | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR cap astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR cap | 1 (2.7) | |

| aggR | 2 (5.5) | |

| aggA astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| cap astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| astA | 1 (2.7) | |

| None | 14 (38.8) | |

| Control (16) | aggR aap | 1 (6.2) |

| aggR cap | 1 (6.2) | |

| aggR astA | 1 (6.2) | |

| aggR | 1 (6.2) | |

| cap | 1 (6.2) | |

| None | 11 (68.7) |

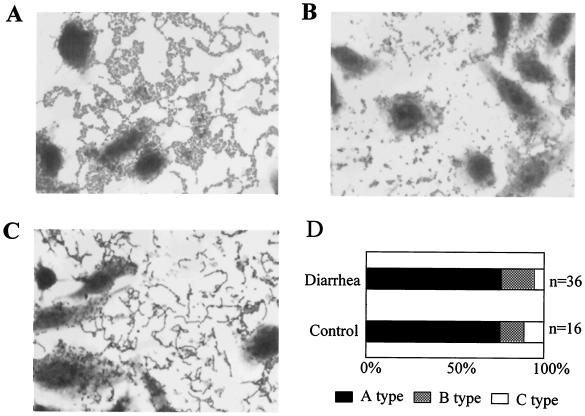

AA patterns of EAEC detected by the HEp-2 adhesion test are shown in Fig. 2. Three AA types were observed in this study: type A, the typical AA pattern with a honeycomb formation; type B, an AA pattern without the typical honeycomb formation; and type C, an AA pattern with lined up cells. The incidence of each AA pattern in the diarrheal group and the control group are shown in Fig. 2D. Most strains showed the typical AA pattern (type A). There was no significant difference among the groups.

FIG. 2.

AA patterns of EAEC detected by HEp-2 adhesion test. (A) Type A: typical AA pattern with honeycomb formation. (B) Type B: AA pattern without typical honeycomb formation. (C) Type C: AA pattern with lined up cells. (D) Incidence of each AA pattern in diarrheal and control groups.

The biofilm-forming ability of EAEC was reported previously (18, 39). To compare the biofilm-forming abilities of AggR-positive and AggR-negative EAEC strains, we performed a quantitative biofilm assay. There was no significant difference between AggR-positive and -negative EAEC strains in the diarrheal group: AggR-positive strains, 0.788 ± 0.564 (mean optical density ± standard deviation); AggR-negative strains, 0.863 ± 0.553.

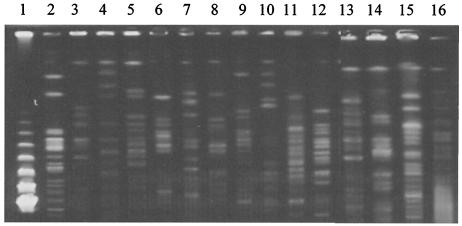

Fifteen different genotypes were observed by PFGE analysis among 19 AggR-positive EAEC strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

PFGE pattern digested by XbaI. Lane 1, marker (lambda DNA ladder); lines 2 to 16, 15 representative patterns observed among 19 AggR-positive EAEC strains in the diarrheal group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, E. coli isolates from the stools of children with diarrhea and from those of healthy children in Mongolia were investigated for the presence of the selected virulence factors of EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, EHEC, and EAEC. Reports from other developing countries have shown that ETEC, EPEC, and EAEC are significantly associated with diarrhea (1, 3, 13, 30, 36). In the present study, all classes of DEC except EHEC were found in the diarrheal group. The observed differences between recovery rates in the diarrheal and the control groups for EPEC, ETEC, and EIEC showed significant association with diarrhea. Notably, the results observed with ETEC, in which ST-producing strains showed stronger association with diarrhea than strains producing LT and both ST and LT, agreed with the results of several other studies (1, 25). Previous reports from developing countries have shown a significant association of typical EPEC strains (eae+ bfpA+ stx) with diarrhea (1, 19, 36). Some recent reports from developed countries have shown that atypical EPEC strains (eae+ bfpA) are more prevalent than typical EPEC strains (29, 41). In this study, we found both typical and atypical EPEC strains significantly more often in the diarrheal group than in controls. EHEC strains were not found in the diarrheal group, which is in agreement with studies in other developing countries, in which EHEC plays a less important role in childhood diarrhea (25, 27, 32). Human infections due to EHEC are primarily associated with the consumption of fecally contaminated foodstuffs. The low incidence of EHEC in our study could be attributable to the lack of consumption of raw meat or vegetables in Mongolia.

According to the 2002 statistical data from the Center for Health Statistics in Mongolia, the major bacterial enteric pathogen is Shigella (83%), followed by Salmonella (8.2%). In the two hospitals participating in our study, 70% of bacterial cases were caused by Shigella and 10% were caused by Salmonella, followed by E. coli and other pathogens (S. Erdene, personal communication). However, the significance of E. coli as an enteric pathogen has been underestimated, because the virulence factors of DEC have not been evaluated. This report could be important for future studies of the epidemiology of DEC in Mongolia.

A possible methodological limitation is the fact that the diarrheal group in our study may include some patients with viral enterocolitis, because the tests for viral enteric pathogens were not fully available. Furthermore, we subcultured only one colony of E. coli on a plate. Subculturing multiple colonies might have yielded a higher incidence of DEC and led to the detection of two categories of DEC in a patient. Even assuming these limitations, our data demonstrated that a variety of DEC strains exist in Mongolia and that they are associated with sporadic diarrhea in children. The microbiological laboratories in Mongolia only test for some EPEC and ETEC serotypes to detect DEC. The development of widely available tests for DEC, including molecular diagnostic methods and the HEp-2 cell adherence test, will be needed. Furthermore, national basic research studies of the epidemiology of DEC in Mongolia must include not just the city area but also the outer urban and rural areas, where the hygiene is not as good and social levels are not as high as in the city.

EAEC was discovered in 15.1% of cases in the diarrheal group and appeared to be the most prevalent pathogen among DEC categories. These cases seem to be the first EAEC infections ever diagnosed in Mongolia. There are an increasing number of reports showing that EAEC is associated with diarrhea. Studies in Brazil, India, southwest Nigeria, Congo, and Iran have noted that EAEC strains are important emerging agents of pediatric diarrhea (3, 4, 12, 24, 36). The pathogenic mechanisms of EAEC infection are only partially understood and are most consistent with mucosal colonization followed by secretion of enterotoxins and cytotoxins. However, there appears to be significant heterogeneity of virulence among EAEC isolates, in part due to lack of specificity in the HEp-2 adherence assay. A few reports have evaluated the prevalence of EAEC virulence genes in strains isolated from case and control studies (9, 24, 31, 44). In the present study, the plasmid-borne genes aggR, aggA, aafA, agg-3a, pet, aap, aatA, and capU and the chromosomal gene set were assessed as pathogenic genes responsible for the expression of adherence and cytotoxin production.

In our study, the incidence of AggR-positive EAEC was significantly higher in the diarrheal group than in the control group, while there was no difference between the prevalences of AggR-negative EAEC in the two groups. These results suggest that AggR-negative EAEC may be less important in the pathogenesis of diarrhea or that it may be avirulent. Some other epidemiological studies have suggested greater pathogenicity of AA probe-positive strains than of probe-negative strains (9, 24). AggR was originally described as a protein required for the expression of AAF/I (17, 21) and was subsequently also shown to be required for AAF/II expression (8). More recently, AggR has been shown to be required for the expression of the aap (see below) and aatA (22) genes. Dudley and Nataro have found that chromosomal genes are also under the control of AggR (unpublished data). Therefore, it is likely that the aggR gene serves as a marker for truly virulent EAEC strains, which express a package of virulence genes. Our data are consistent with this paradigm. Analogous to the term “typical EPEC,” Nataro has recently suggested the term “typical EAEC” to refer to strains expressing the AggR regulon (16).

Recently, the aap gene was reported to encode a secreted 10-kDa protein that appears to coat the bacterial surface and thereby promote the dispersal of EAEC on the intestinal mucosa. It was also shown that this protein is immunogenic in a human EAEC challenge model (38). The incidence of this gene among EAEC strains isolated in one district has not been reported. In the present study, the aap gene was found in 22.2% of the diarrheal group and 6.2% of the control group of EAEC, which is lower than the incidence in a previous report (7).

The AAF/I and AAF/II genes were present in 5.5% (2 of 36) and 11.1% (4 of 36), respectively, of EAEC in the diarrheal group. As was found previously in various epidemiological studies, the prevalences of AAF/I and AAF/II appear to vary up to 19% according to the geographical area. In Nigerian EAEC strains, they were detected more frequently, in 63.0 and 46.6% of EAEC, respectively, and AAF/II correlated significantly with diarrhea (24). AAF/III has recently been identified and reported to be found in EAEC isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients presenting with persistent diarrhea (2). We examined this fimbria type in different geographical areas and found it in 13.8% of EAEC strains, indicating that this new variant fimbria plays a role in sporadic diarrhea of children in different regions. These three fimbria types were not detected in any of the control EAEC strains, suggesting that these factors are important for the pathogenesis of EAEC. However, considering that only a minority of isolates produced these fimbriae in our study and in others (6, 7), future investigation to find other unknown fimbriae should be carried out. All strains with the fimbrial-type genes were also AggR positive, except for one, which was AAF/I+ and AggR−. In the HEp-2 adhesion test, most EAEC strains showed typical AA adherence (type A), while a minority of EAEC showed atypical AA adherence (type B or C). All the strains harboring AAF/I, AAF/II, or AAF/III showed the typical AA pattern. This result suggests some variations in the adherence pattern of EAEC and the presence of unknown adhesive fimbriae.

Notably, in our study, the EAST1 toxin was found in EAEC, ETEC, and DAEC strains and in many strains not belonging to any diarrheagenic category. It has been shown that EAST1 is not restricted to EAEC isolates, and very few studies have shown an association of this gene with diarrhea (14, 23, 43). In our study, the strains producing EAST1 that did not belong to any recognized DEC categories were significantly associated with diarrhea, suggesting the pathogenetic role of this toxin in our district. Thus, EAST1 may play a role in some epidemiological areas.

In summary the present study shows that EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, and EAEC have significant association with pediatric diarrhea in Mongolia, and especially, that typical EAEC may be an important pathogen causing sporadic diarrhea in this population of children.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Research Fund of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (no. 12470168).

We thank Maamuu Nortmaa at the Mother and Child Health Center, Suuri Bujinlham at the Infectious Disease Hospital, and Jadambaa Olziibat at the Second Clinical Hospital, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, for excellent technical assistance in collecting E. coli strains and Hiroaki Miyanohara at Kagoshima University Hospital Clinical Laboratory for technical support in performing PFGE.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert, M. J., S. M. Faruque, A. S. Faruque, P. K. Neogi, M. Ansaruzzaman, N. A. Bhuiyan, K. Alam, and M. S. Akbar. 1995. Controlled study of Escherichia coli diarrheal infections in Bangladeshi children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:973-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernier, C., P. Gounon, and C. Le Bouguenec. 2002. Identification of an aggregative adhesion fimbria (AAF) type III-encoding operon in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a sensitive probe for detecting the AAF-encoding operon family. Infect. Immun. 70:4302-4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhan, M. K., P. Raj, M. M. Levine, J. B. Kaper, N. Bhandari, R. Srivastava, R. Kumar, and S. Sazawal. 1989. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli associated with persistent diarrhea in a cohort of rural children in India. J. Infect. Dis. 159:1061-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouzari, S., A. Jafari, A. Azizi, M. Oloomi, and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Short report: characterization of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolates from Iranian children. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:13-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke, S. C. 2001. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli—an emerging problem? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeczulin, J. R., S. Balepur, S. Hicks, A. Phillips, R. Hall, M. H. Kothary, F. Navarro-Garcia, and J. P. Nataro. 1997. Aggregative adherence fimbria II, a second fimbrial antigen mediating aggregative adherence in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 65:4135-4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czeczulin, J. R., T. S. Whittam, I. R. Henderson, F. Navarro-Garcia, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:2692-2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elias, W. P., Jr., J. R. Czeczulin, I. R. Henderson, L. R. Trabulsi, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Organization of biogenesis genes for aggregative adherence fimbria II defines a virulence gene cluster in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:1779-1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias, W. P., A. P. Uber, S. K. Tomita, L. R. Trabulsi, and T. A. Gomes. 2002. Combinations of putative virulence markers in typical and variant enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains from children with and without diarrhoea. Epidemiol. Infect. 129:49-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eslava, C., F. Navarro-Garcia, J. R. Czeczulin, I. R. Henderson, A. Cravioto, and J. P. Nataro. 1998. Pet, an autotransporter enterotoxin from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 66:3155-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gascon, J., M. Vargas, L. Quinto, M. Corachan, M. T. Jimenez de Anta, and J. Vila. 1998. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains as a cause of traveler's diarrhea: a case-control study. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1409-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalaluddin, S., P. de Mol, W. Hemelhof, N. Bauma, D. Brasseur, P. Hennart, R. E. Lomoyo, B. Rowe, and J. P. Butzler. 1998. Isolation and characterization of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAggEC) by genotypic and phenotypic markers, isolated from diarrheal children in Congo. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 4:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine, M. M., C. Ferreccio, V. Prado, M. Cayazzo, P. Abrego, J. Martinez, L. Maggi, M. M. Baldini, W. Martin, D. Maneval, et al. 1993. Epidemiologic studies of Escherichia coli diarrheal infections in a low socioeconomic level peri-urban community in Santiago, Chile. Am. J. Epidemiol. 138:849-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menard, L. P., and J. D. Dubreuil. 2002. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 (EAST1): a new toxin with an old twist. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 28:43-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nataro, J. P. 2002. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli, p. 1463-1504. In M. Sussman (ed.), Molecular medical microbiology, vol. 3. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 16.Nataro, J. P. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. In W. M. Scheld, J. M. Hughes, and B. E. Murray (ed.), Emerging infections 6. ASM Press, Washington, D.C., in press.

- 17.Nataro, J. P., Y. Deng, D. R. Maneval, A. L. German, W. C. Martin, and M. M. Levine. 1992. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 60:2297-2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nataro, J. P., J. B. Kaper, R. Robins-Browne, V. Prado, P. Vial, and M. M. Levine. 1987. Patterns of adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 6:829-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nataro, J. P., T. Steiner, and R. L. Guerrant. 1998. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:251-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nataro, J. P., D. Yikang, D. Yingkang, and K. Walker. 1994. AggR, a transcriptional activator of aggregative adherence fimbria I expression in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:4691-4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishi, J., J. Sheikh, K. Mizuguchi, B. Luisi, V. Burland, A. Boutin, D. J. Rose, F. R. Blattner, and J. P. Nataro. 2003. The export of coat protein from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli by a specific ATP-binding cassette transporter system. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45680-45689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishikawa, Y., Z. Zhou, A. Hase, J. Ogasawara, T. Kitase, N. Abe, H. Nakamura, T. Wada, E. Ishii, and K. Haruki. 2002. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from stools of sporadic cases of diarrheal illness in Osaka City, Japan between 1997 and 2000: prevalence of enteroaggregative E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene-possessing E. coli. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 55:183-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okeke, I. N., A. Lamikanra, J. Czeczulin, F. Dubovsky, J. B. Kaper, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Heterogeneous virulence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains isolated from children in Southwest Nigeria. J. Infect. Dis. 181:252-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okeke, I. N., A. Lamikanra, H. Steinruck, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains from cases of childhood diarrhea in provincial southwestern Nigeria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okeke, I. N., and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:304-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oyofo, B. A., D. Subekti, P. Tjaniadi, N. Machpud, S. Komalarini, B. Setiawan, C. Simanjuntak, N. Punjabi, A. L. Corwin, M. Wasfy, J. R. Campbell, and M. Lesmana. 2002. Enteropathogens associated with acute diarrhea in community and hospital patients in Jakarta, Indonesia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 34:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pabst, W. L., M. Altwegg, C. Kind, S. Mirjanic, D. Hardegger, and D. Nadal. 2003. Prevalence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli among children with and without diarrhea in Switzerland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2289-2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paciorek, J. 2002. Virulence properties of Escherichia coli faecal strains isolated in Poland from healthy children and strains belonging to serogroups O18, O26, O44, O86, O126 and O127 isolated from children with diarrhoea. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:548-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul, M., T. Tsukamoto, A. R. Ghosh, S. K. Bhattacharya, B. Manna, S. Chakrabarti, G. B. Nair, D. A. Sack, D. Sen, and Y. Takeda. 1994. The significance of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli in the etiology of hospitalized diarrhoea in Calcutta, India and the demonstration of a new honey-combed pattern of aggregative adherence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 117:319-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piva, I. C., A. L. Pereira, L. R. Ferraz, R. S. Silva, A. C. Vieira, J. E. Blanco, M. Blanco, J. Blanco, and L. G. Giugliano. 2003. Virulence markers of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from children and adults with diarrhea in Brasilia, Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1827-1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porat, N., A. Levy, D. Fraser, R. J. Deckelbaum, and R. Dagan. 1998. Prevalence of intestinal infections caused by diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Bedouin infants and young children in Southern Israel. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 17:482-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramotar, K., B. Waldhart, D. Church, R. Szumski, and T. J. Louie. 1995. Direct detection of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in stool samples by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:519-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robins-Browne, R. M., and E. L. Hartland. 2002. Escherichia coli as a cause of diarrhea. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17:467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sang, W. K., T. Iida, H. Yamamoto, S. M. Saidi, M. Yoh, P. G. Waiyaki, T. Ezaki, and T. Honda. 1996. Prevalence of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in Kenyan children. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 14:216-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scaletsky, I. C., S. H. Fabbricotti, S. O. Silva, M. B. Morais, and U. Fagundes-Neto. 2002. HEp-2-adherent Escherichia coli strains associated with acute infantile diarrhea, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:855-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sethabutr, O., M. Venkatesan, G. S. Murphy, B. Eampokalap, C. W. Hoge, and P. Echeverria. 1993. Detection of Shigellae and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli by amplification of the invasion plasmid antigen H DNA sequence in patients with dysentery. J. Infect. Dis. 167:458-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheikh, J., J. R. Czeczulin, S. Harrington, S. Hicks, I. R. Henderson, C. Le Bouguenec, P. Gounon, A. Phillips, and J. P. Nataro. 2002. A novel dispersin protein in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 110:1329-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheikh, J., S. Hicks, M. Dall'Agnol, A. D. Phillips, and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Roles for Fis and YafK in biofilm formation by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:983-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stacy-Phipps, S., J. J. Mecca, and J. B. Weiss. 1995. Multiplex PCR assay and simple preparation method for stool specimens detect enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli DNA during course of infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1054-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trabulsi, L. R., R. Keller, and T. A. Tardelli Gomes. 2002. Typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:508-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukamoto, T. 1996. PCR methods for detection of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (localized adherence) and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 70:569-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vila, J., A. Gene, M. Vargas, J. Gascon, C. Latorre, and M. T. Jimenez de Anta. 1998. A case-control study of diarrhoea in children caused by Escherichia coli producing heat-stable enterotoxin (EAST-1). J. Med. Microbiol. 47:889-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vila, J., M. Vargas, I. R. Henderson, J. Gascon, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in traveler's diarrhea strains. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1780-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu, J. G., B. Q. Cheng, Y. P. Wu, L. B. Huang, X. H. Lai, B. Y. Liu, X. Z. Lo, and H. F. Li. 1996. Adherence patterns and DNA probe types of Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheal patients in China. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yatsuyanagi, J., Y. Kinouchi, S. Saito, H. Sato, and M. Morita. 1996. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains harboring enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAggEC) heat-stable enterotoxin-1 gene isolated from a food-borne like outbreak. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 70:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]