Abstract

We present a comparison between the electron stimulated desorption (ESD) of anions from DNA samples prepared by lyophilization (an example of poorly organized or nonuniform films) and molecular self-assembly (well-ordered films). The lyophilization (or freeze-drying) method is perhaps the most frequently employed technique for forming DNA films for studies of low-energy electron (LEE) interactions leading to DNA damage; however, this technique usually produces nonuniform films with considerable clustering which may affect DNA configuration and enhance sample charging when the film is irradiated. Our results confirm the general validity of ESD measurements obtained with lyophilized samples, but also reveal limitations of lyophilization for LEE studies on DNA films. Specifically we observe some modulation of structures, associated with dissociative electron attachment, in the anion yield functions from different types of DNA film, confirming that conformational factors play a role in the LEE induced damage to DNA.

I. INTRODUCTION

During the past decade, experiments have shown that the low-energy electrons (LEEs) such as those produced in large numbers by highly ionizing radiation (~40 000 per MeV of deposited energy)1,2 can cause damage to plasmid and synthetic oligonucleotide DNA.3–6 Boudaïfa et al.3 analyzed by gel electrophoresis strand break damage induced in lyophilized (i.e., freeze-dried) plasmid DNA by 3–20 eV electrons. Both single and double strand break lesions were observed; their yields showed threshold energies lower than 5 eV and maxima at about 10 eV. These thresholds at low energy, and the strong modulation of strand break yield with electron energy, led the authors to propose that damage occurred as a result of electron attachment to DNA subunits, via the formation of transient negative ions (TNI) and subsequent bond dissociation. Later studies have attempted to better understand the damage mechanisms initiated by LEE in DNA. One technique employed for this purpose is the electron stimulated desorption (ESD) of anionic fragments.5,7 Experiments investigating the ESD from thin films of DNA have shown that two processes are involved in the formation and desorption of negative fragment ions; dissociative electron attachment (DEA) and dipolar dissociation (DD).5–8 For electrons with energies lower than 15 eV, DEA is the primary process and proceeds via formation of a TNI which dissociates into a stable negative ion and one or more neutral fragments (e.g., for a diatomic molecule AB, AB + e− → A− + B°). The DD process usually occurs at electron energies above 15 eV. In the DD process, an electronically excited molecule dissociates into positive and negative ions. As summarized elsewhere,9–11 DEA, DD, and, more generally, ESD processes in the condensed films, depend highly on the film environment e.g., properties such as film morphology and composition, which can modulate electron scattering within the film and hence modify the yield functions of desorbed species anions.

Several preparation techniques including lyophilization and molecular self-assembly have previously been used to form DNA film target films for LEE irradiation studies.6 In the lyophilization technique, a small aliquot of the DNA in solution (usually pure water) is placed on a substrate and is lyophilized (i.e., first frozen, then dried by the sublimation of water in a partial vacuum) within a sealed glove box.4 In this method, a relatively thick film of DNA is formed and its thickness is estimated from the mass of DNA deposited, the surface area of the deposit, and the known density of DNA (1.7 g/cm3).12 DNA films have also been prepared by molecular self-assembly of the thiolated, linear molecule on gold substrates.13–18 Such a method forms well-organized and relatively clean films.19,20 The common protocol for the preparation of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of DNA involves immersing a freshly prepared gold substrate into a solution containing the thiolated oligonucleotide. In this method, a single layer of DNA is formed by a strong chemical bond between sulfur and the gold surface (45 kcal/mol).21 The surface condition of the gold substrates prior to the SAM formation strongly influences the efficiency of the molecules adhesion to the gold plates. Thus, it is important to remove contaminants such as hydrocarbons and oxide layers from the gold surface before SAM formation.22–25

The SAM technique usually results in uniform and well-defined, ordered monolayers. In the SAM configuration, DNA molecules are oriented at some small angle relative to the normal of the gold surface, dependent on the length of the thiolated oligonucleotides.26 In contrast, lyophilization produces nonuniform films of DNA with noticeable amounts of clustering in the film.27 The objective of the present work is, using these two methods for DNA film preparation, to examine the effect of the local molecular arrangement and film configuration on the ESD of anions.

The ESD results from the SAM and lyophilized films are compared and discussed in terms of film order and composition. This comparison is of particular importance for future experiments and the interpretation of their results. While lyophilization is a procedurally simple method for the preparation of DNA films on metal substrates, it is unclear to what extent the resulting nonuniform film thickness and clustering of the molecules27 may affect the configuration of DNA and charge accumulation during LEE bombardment. Thus, differences between the ESD results obtained from lyophilized and SAM-DNA films would indicate the limitations of lyophilization as a technique of film preparation for LEE interactions and determine the factors limiting the validity of results recorded with this method.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

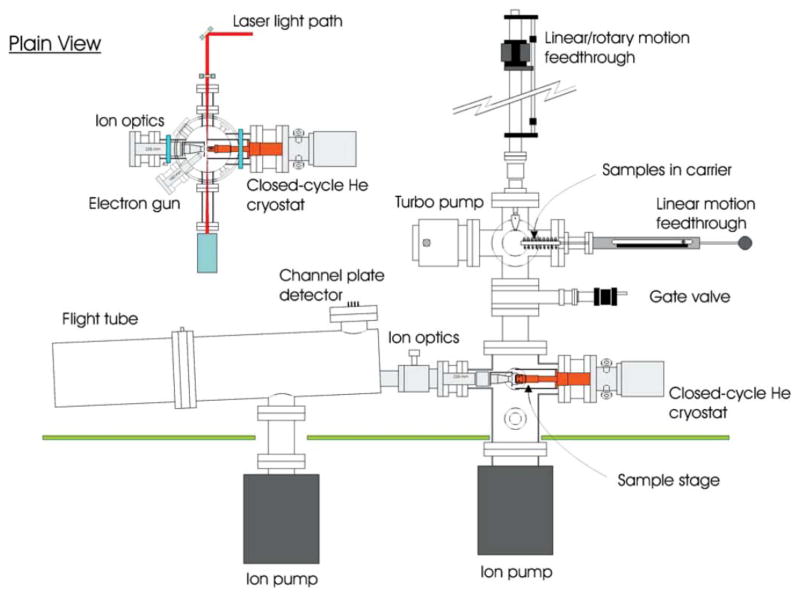

The ESD measurements were performed using a high-sensitivity time-of-flight (TOF) analyzer under ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) conditions (see Fig. 1). The present experiments have been facilitated by the recent addition of a load-lock. A detailed description of the TOF system and its use for ion desorption measurements and its specifications are given elsewhere.28

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the apparatus, including the time-of-flight mass analyzer and sample load-lock.

The synthetic 10-mer oligonucleotides of sequence 5′AAAGGACAAA (G = guanine, A = adenine, and C = cytosine) were purchased by University Core DNA services at the University of Calgary. Phosphothiolated oligonucleotides were also prepared with one sulfur substitution with the oxygen doubly bonded to phosphorous. For this work, a 10-mer oligonucleotide was chosen to form a relatively well-ordered film. According to the work of Petrovykh et al.26 SAM-DNA film order decreases as the number of bases in the oligonucleotide increases from 5- to 25-mers. Gold plates were used as substrates and purchased from the physics department at the University of Sherbrooke. The gold plates contain three layers: gold, chromium, and silicon with thicknesses of 300, 4, and 4 mm, respectively. The thin chromium layer is applied to optimize adhesion of the gold to the silicon layer. Gold plates were cleaned prior to the deposition of DNA (via either molecular self-assembly or lyophilization) by multiple exposures to UV/ozone29–31 and rinsing with ethanol and doublydistilled, deionized water (pure water) as explained previously.25

The self-assembled DNA films (SAM-DNA) were prepared by placing 25 μl of solution containing 0.34 μg of purified phosphothiolated oligonucleotide in pure water onto an ozone-cleaned gold substrate. Invariably, this procedure forms a flattened drop having a cross sectional area of about 0.8 cm2. Plates were left at room temperature in a closed container for about 12 h, allowing the DNA to chemisorb via terminal thiols onto the gold surface. After SAM formation, the plates were rinsed by immersion in pure water, three times for periods of 20 min, to remove unbound molecules. Samples were dried under a stream of N2 gas prior to their transfer into the load-lock chamber.

Lyophilized samples were prepared within a glove box in the following manner. Using a micropipette, 25 μl of solutions containing either 0.135, 0.27, or 0.54 μg of the purified 10-mer oligonucleotide dissolved in pure water were deposited onto ozone-cleaned gold substrates to form flattened drops, typically having a cross sectional area of ~0.8 cm2. Samples were then frozen at –55 °C by thermal contact with a liquid nitrogen cooled Al plate, and transferred into a separate smaller vessel where they were lyophilized using a hydrocarbon-free sorption pump under a pressure of 5 mTorr. The lyophilized DNA of 0.135, 0.27, and 0.54 μg formed films of 2.5-, 5-, and 10-monolayer-thickness (5 monolayers = 2.5 nm), respectively, (assuming a density for DNA of 1.7 g/cm3).12 Such thin oligonucleotides films are necessary for these experiments to minimize sample charging by incident electrons.32 The charging of the films during experiments was monitored by measuring the onset of current transmitted through the films.33,34

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were also performed to verify DNA adsorption onto the gold substrates. The x-ray source (15 kV, 350 W) of the previously described XPS spectrometer35 uses an Al anode. The x-ray beam impinges onto the sample surface at an incident angle of 72° relative to the substrate, while the hemispherical electron energy analyzer is positioned normal to the sample surface. The pass energy was set to 11.75 eV.

Once formed (either by lyophilization or self-assembly) the DNA samples were transferred individually from the load-lock vacuum system (base pressure <1 × 10−8 Torr) into the UHV analysis chamber. The films were bombarded by LEE from an electron gun (Kimball Physics ELG-2) with a stated energy resolution of 0.4 eV FWHM. The beam was incident at an angle of 45° with respect to the substrate and focused into an estimated spot-size of ~1 mm2. The electron gun was operated in a pulsed mode of 800 ns duration at a rate of 5 kHz. For typical experiments, the incident electron energy was varied between 0.1 and 20 eV and the electron gun adjusted to provide an incident current (time-averaged) of 4 nA (measured at 10 eV). The electron energy scale was calibrated to within ± 0.3 eV with respect to the vacuum level (Evac = 0 eV) by measuring the onset of the transmitted current through the film. A short time (~10 ns) after each pulse of the electron beam, a negative potential (rise/fall time 30 ns, pulse width of 2 μs) is applied to the gold substrate and des-orbed anions are propelled into the entrance of a reflectron TOF mass analyzer which is positioned normal to the film surface at a distance of 10 mm. Using a definition of resolving power R = m/Δm, where Δm is the minimum peak separation at which two ion signals (of average mass m) can be distinguished, we have measured the resolving power of the TOF to be greater than 500, which for the masses observed in Sec. III corresponds to a resolution of a few hundredths of an atomic mass unit. By recording the desorbed ion signals as a function of incident electron energy, a “yield function” for each desorbed ion was obtained.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

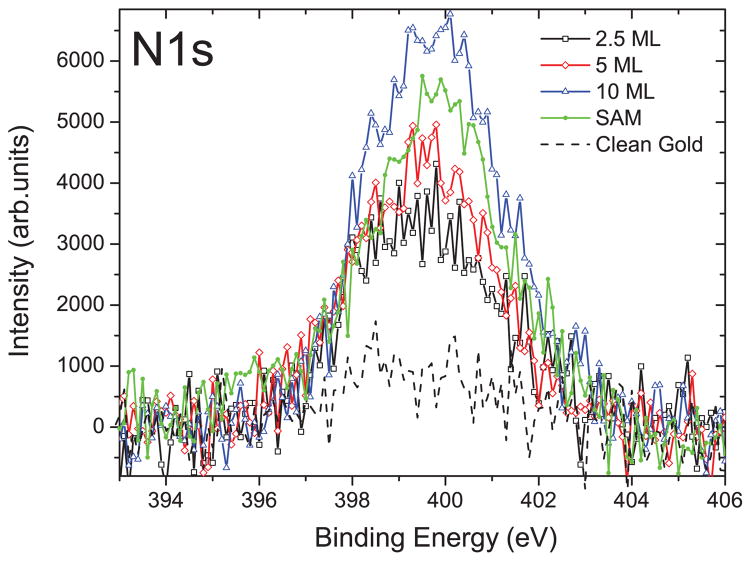

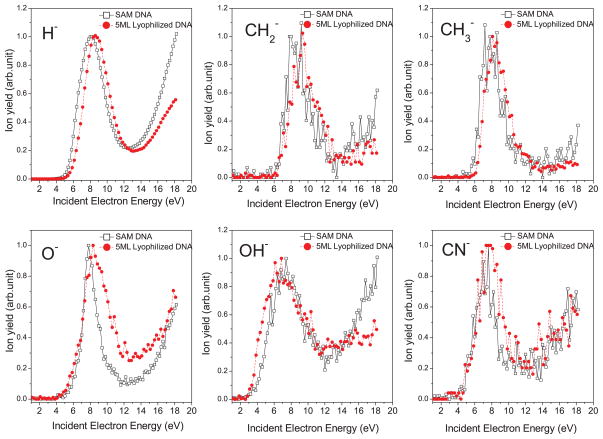

Figure 2 presents XPS measurements of the nitrogen, N1s photoelectron peak (binding energy of ~400 eV). The figure indicates that the 5-monolayer-thick lyophilized DNA sample contains roughly the same amount of nitrogen as the SAM-DNA, which suggests that these two sample types contain similar quantities of DNA. We have then, in Fig. 3, chosen to compare anion yield functions obtained from a 5-monolayer-thick film of lyophilized DNA and a SAM-DNA film. In this figure, the curves have been normalized to the same peak intensity to allow for easier comparison. The yield functions presented in Fig. 3 are broadly consistent with earlier experiments on anion desorption from DNA films.7,8 The most intense signals are formed for desorption of the following anions: H− (1 amu), CH2− (14 amu), CH3−/NH−(15 amu), O−/NH2− (16 amu), OH− (17 amu), and CN−(26 amu). Nitrogen containing species such as NH− and NH2− can in principle only form and desorb via fragmentation of a DNA base (rather than that of the sugar or phosphate), which in the present experiments could be A, C, or G. However, in earlier gas-phase studies of the isolated bases36–38 and ESD measurements for thin films of DNA bases,39 fragments of mass 16 amu were only observed from the bases containing an O atom (i.e., for G, C, and T but not A), and no 15 amu fragment was seen from any base. These results have been taken in earlier studies of ESD from DNA,5,7,40 as evidence that the signals of mass 15 and 16 amu correspond to CH3− and O−, respectively, and derive from the sugar-phosphate backbone. The yield functions of most anions exhibit energetic thresholds between 4 and 5 eV, except that for OH−, which has its threshold at 2.6 ± 0.3 eV. As in earlier studies,7,8 resonant features are observed in the range 6–9 eV, indicating that DEA is responsible for formation and desorption of these anions at low electron energies. The anion signals also show a monotonic increase at energies above 14 or 15 eV, indicating that DD also contributes to the desorption of anions at higher energies.

FIG. 2.

XPS measurements of N1s (binding energy of ~400 eV) peak for SAM-DNA, 2.5-, 5-, and 10-monolayer-thick lyophilized DNA films where intensity is proportional to the amount of DNA chemisorbed on a gold substrate.

FIG. 3.

Normalized anion yield functions from SAM-DNA and 5-monolayer-thick DNA film.

Table I compares the energetic thresholds, energies, and widths of the resonance structures seen in the anion yield functions of Fig. 3 for the SAM-DNA and 5-monolayer-thick lyophilized DNA. It can be seen that the desorption thresholds and resonance energies of both films are in a good agreement in all cases (i.e., the difference in energies is within our experimental uncertainty).

TABLE I.

Energy and width of electron resonances and threshold energies observed in anion yield functions from self-assembled and lyophilized DNA films. Resonance energies were obtained “by-eye.” The widths of the resonance structures are measured at half maximum.

| Desorbed anions | Method of film preparation | Threshold energy (eV) | Resonance energy (eV) | Width of the resonance structure (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H- | Self-assembly | 5 | 8.2 | 3.5 |

| Lyophilization | 5.1 | 8.6 | 3.5 | |

| CH2− | Self-assembly | 6.2 | 8.8 | ~3 |

| Lyophilization | 6.3 | 9 | ~3.4 | |

| CH3−/NH− | Self-assembly | 5.6 | 7.7 | ~2.4 |

| Lyophilization | 6.1 | 8.1 | ~2.9 | |

| O−/NH2− | Self-assembly | 5.3 | 7.8 | 1.7 |

| Lyophilization | 4.9 | 8.3 | ~3.1 | |

| OH− | Self-assembly | 2.7 | 7.1 | ~4 |

| Lyophilization | 2.65 | 6.7 | ~6 | |

| CN− | Self-assembly | 4.8 | 7.0 | ~2.3 |

| Lyophilization | 4.6 | 7.7 | ~3.35 |

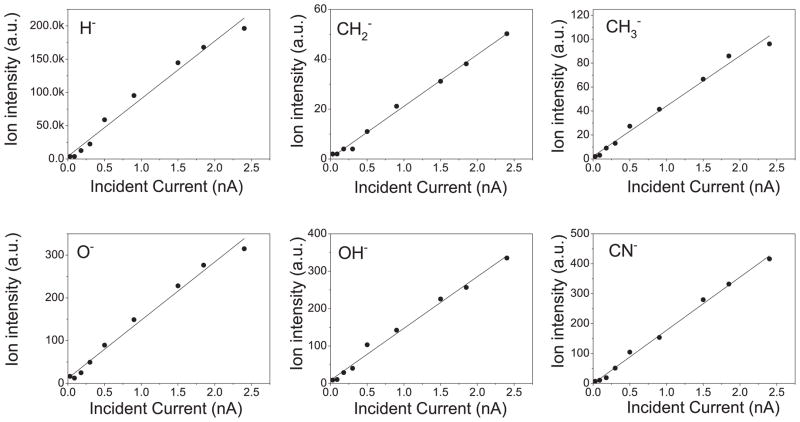

As shown in Fig. 4, the variation of the anion desorption signals from a lyophilized 10-monolayer-thick DNA film with incident electron current at 8 eV is linear, as was the case for all samples studied. This linear dependence indicates that the desorption signals are the result of single scattering events (at least for the current range investigated) and that the detection of these anions follows either direct dissociation of an unmodified adsorbed molecule or scattering of the resultant fragments with other adsorbed molecules, which are otherwise unmodified by electron irradiation.

FIG. 4.

Variation of anion desorption signal from 10-monolayer-thick lyophilized DNA with incident electron current, at an incident electron energy of 8 eV.

Careful study of Fig. 3 shows that the resonant structures seen in the anion yield functions from lyophilized DNA are broader than those seen from SAM-DNA except for H−. In our experiment, measurements were performed using incident electron pulses of ~800 ns duration, during which time anions of all masses are desorbed prior to the application of the extraction voltage and their injection into the TOF analyzer. Fragments with low mass such as H− will, for the same kinetic energy, have higher velocities than heavier anions and therefore travel further from the film before the extraction voltage is applied. Consequently, H− ions produced early during a long electron pulse escape the detection region and are detected with less efficiency than those H− ions produced at the end of the pulse. However, the detection efficiency for the more massive ions does not change greatly over the duration of the electron pulse.28

It is likely that the broader features seen in the anion yield functions from the lyophilized DNA derive in some manner from the method of film preparation. Previously, it has been shown9,10 that the signal of desorbed anions generated by DEA (and also DD) depends strongly on the local molecular environment. Environmental effects modulating desorption have been categorized into two groups: intrinsic and extrinsic.41 Intrinsic effects modify the TNI states participating in DEA by altering their properties such as lifetime, energy, and the availability of specific decay channels. In contrast, extrinsic factors modulate the interactions of LEE prior to attachment (and the formation of a TNI) or the interactions of fragment species formed after dissociation. Extrinsic factors include, for example, the availability of competing energy loss processes, in the former case, and the possibility of reactive-ion scattering in the latter.

As described by O’Malley,42 within a local complex potential curve crossing model, the DEA cross section can be written as

| (1) |

where Ps is the survival probability of the anions against the electron autodetachment, E is the incident electron energy, and σcap represents the capture cross section. The capture cross section can be defined as

| (2) |

where λ is the de Broglie wavelength of the incident electron energy, g is a statistical factor, and χν is the normalized vibrational nuclear wave function. Γa represents the local energy width of the AB− state in the Franck–Condon (FC) region, and Γd is the extent of the AB− potential in the FC region. The width of the transient anion state (Γa) defines autodetachment lifetime τa, τa(R) = Ħ[Γa(R)], such that the survival probability of the temporary anion can be expressed as

| (3) |

where RE is the bond length of the anion at energy E, and Rc is the intermolecular separation where for R > Rc autodetachment is no longer possible. Finally, if we introduce τ̄a as an average lifetime, the cross section for the DEA reaction, σDEA, becomes9

| (4) |

In Eq. (4), τ̄c(E ) ≡ | Rc − RE |/ν where ν is the average velocity of the fragments during dissociation. It is apparent then that the DEA cross section varies exponentially with the lifetime of the transient anion. The signal of desorbed anions which results from the DEA process can thus depend on any environmental factors which modify properties of the TNI including their lifetime. One of the most important intrinsic factors influencing the ESD of the anions arises from interaction between the TNI and the induced image charge in the molecular film and metal surfaces.11 This surface polarization energy lowers the energy of the TNI which—at distances suitably far (>1 nm) from the supporting gold substrate— both increases the autodetachment lifetime and decreases the internuclear separation over which autoionization operates [i.e., Rc is reduced in Eq. (3)].43,44 Consequently, the DEA cross section (and hence ESD) is enhanced. At shorter distances from the metal surface, this local electric field decreases the capture cross section and as a result reduces the autodetachment lifetime by increasing electron transfer to the metal.11,45 The shortening of lifetime also increases the width of the resonance structure in the anions’ yield functions.11 Furthermore, as a result of the shorter autodetachment lifetime of TNI, the desorbed signal intensity of the anions decreases, i.e., there is not sufficient time for a TNI to dissociate into an anion before the electron detachment. Interestingly, in our experimental results, comparison between a 5-monolayer-thick film of lyophilized DNA and a SAM-DNA film shows that the anion yield functions from lyophilized DNA have generally slightly broader features (see Table I) with higher signal intensities (not shown here). The broadening of the resonance peaks cannot arise from a shorter lifetime of the TNI, since in this case the magnitude of the signal would also be smaller for lyophilized DNA. Such broadening could therefore arise from some ‘fluctuation’ of electron energy. As stated earlier in the case of formation of DNA films through self-assembled monolayers, the molecular environment is usually well-defined19,20 whereas in the lyophilization technique the molecular environment is less controllable and is likely not as well-ordered and uniform. As discussed, the local electric fields can have considerable influence on the intensity and width of the desorbed anions’ yield functions. In lyophilized DNA the local electric field will vary, from point-to-point, across the sample and as a result so will the local effective incident electron energy and the energy of potential TNI. Together these effects will broaden the resonance features observed within yield functions.

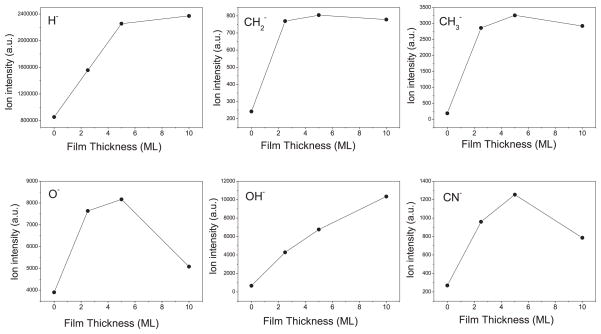

Figure 5 shows how the desorbed anion signal, integrated between incident electron energies of 0.1 and 20 eV, varies with the thickness of lyophilized DNA samples. We see from Fig. 5 that as the thickness of DNA film increases from 0 to 5 monolayers, the intensity of the anion signals also increases. However, beyond 5 monolayers, different trends are seen: the yield of CH2− and CH3− saturate or decrease only slightly, while the signals of O− and CN− drop dramatically. In contrast, the signal of OH− increases as a function of thickness over the entire range of thicknesses. Such variation of anion yield with sample thickness has been discussed by Bazin et al.46 According to these authors, several factors influence the ESD signal. In the condensed phase, the ions (typically of low kinetic energy) are desorbed primarily from the uppermost surface layer of the film, but also from the subsurface region.47 Accordingly, we observe that the yields of anions increase as the thickness of the film increases from 2.5- to 5-monolayers-thick confirming that anions also desorbed from subsurface layers of DNA film. However, the amount of DNA available on the surface is not the only factor responsible for the observed increase in the magnitude of desorbing anion signal with thickness. As the thickness of the film increases,46 the image-charge induced polarization energy at the surface of the film decreases, allowing anions of lower kinetic energy to leave the surface of thicker films. For example, the signal of OH− seen in our ESD experiment increases over the entire range of studied film thickness, indicating that this signal may be very sensitive to the decrease of the image force, possibly due to the low kinetic energy distribution of OH− ions. In contrast, anions such as H−, CH2−, and CH3− show no enhancement in their intensities at film thicknesses beyond 2.5 to 5 ML. This suggests that for H− the escape range lies at around 4 monolayers, whereas for the other two it is almost about 2 monolayers. Furthermore, beyond these ranges the kinetic energies of the H−, CH2−, and CH3− ions would be sufficiently large to escape the influence of the reduction of the image potential.

FIG. 5.

Variation of the anion desorption signal (integrated over incident electron energies (between 0.1 and 20 eV) with thickness (in monolayers) of a lyophilized DNA film on gold substrate.

The decrease of O− and CN− signals for 10-monolayer-thick films may provide an example of the limitations of the lyophilization method. Such a decrease cannot be attributed in the usual way to intrinsic and extrinsic factors that influence ESD signals from thin films. A decrease at higher thickness could occur because of clustering of the samples, which would cause surface charging and decrease effective electron energy; or a drastic change in the configuration of DNA which would change the DEA parameters. In the latter case only certain sites could be modified, thus accounting for the selectivity in the decrease of the anion signals at 10-monolayer-thick film. We therefore conclude from the behavior of the O− and OH− signals that the 5-monolayer-thick film (i.e., 2.5 nm) is a reasonable thickness to be chosen when studying the interactions of LEE with DNA. This thickness is sufficient to isolate most of the DNA from the metal substrate, to avoid the strong image-charge induced polarization by the metal substrate, and to limit charging of the film.32

IV. CONCLUSION

In our study, low-energy (0.1–20 eV) electrons incident onto SAM-DNA and lyophilized DNA films induced the desorption of H−, CH2−, CH3−/NH−, O−/NH2−, OH−, and CN− anion fragments. The yield functions of these anions exhibit strong resonance features between 6 and 9 eV, confirming that DEA is involved in the formation and desorption of these anions. The monotonic increase of the signal above 14–15 eV indicates that the DD process is involved in producing anions above 15 eV. Most importantly, we have shown that with 5-monolayer-thick films of lyophilized single-stranded DNA, there exists little difference between the results obtained with lyophilized and SAM-DNA films. Our results thus confirm lyophilization as a useful technique of film preparation for LEE investigations.

The remaining, subtle differences existing between the resonance structure seen in the anion yield functions from ordered (SAM-DNA) and disordered (lyophilized DNA) films demonstrate that, in common with other systems,9,10,41 intermolecular arrangement plays a role in determining the desorbed ESD yield and consequently the damage induced by LEE in DNA. These differences are explained in terms of the modification of intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting ESD.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada. The authors also thank Pierre Cloutier for his technical support.

References

- 1.Uehara U, Nikjoo H, Goodhead DT. Radiat Res. 1999;152:202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaVerne JA, Pimblott SM. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:10540. [Google Scholar]; Radiat Res. 1995;141:208. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudaïffa D, Cloutier P, Hunting D, Huels MA, Sanche L. Science. 2000;287:1658. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudaïffa D, Cloutier P, Hunting D, Huels MA, Sanche L. Radiat Res. 2002;157:227. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)157[0227:csflee]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan X, Cloutier P, Hunting D, Sanche L. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90:208102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.208102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanche L. Low-energy electron interaction with DNA: Bond dissociation and formation of transient anions, radicals, and radical anions. In: Greenberg Marc M., editor. Radical and Radical Ion Reactivity in Nucleic Acids Chemistry. Wiley; Hoboken: 2009. p. 239. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan X, Sanche L. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:198104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.198104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirsaleh-Kohan N, Bass AD, Sanche L. J Phys Conf Ser. 2010;204:012005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bass AD, Sanche L. Low Temp Phys. 2003;29:202. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bass AD, Sanche L. Radiat Phys Chem. 2003;68:3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mozejko P, Bass AD, Parenteau L, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 2004;121:10181. doi: 10.1063/1.1807813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams RLP, Knowler JT, Leader DP. The Biochemistry of the Nucleic Acids. 10. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrovykh DY, Kimura-Suda H, Whitman LJ, Tarlov MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5219. doi: 10.1021/ja029450c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moses S, Brewer SH, Lowe LB, Lappi SE, Gilvey LBG, Sauthier M, Tenent RC, Feldheim DL, Franzen S. Langmuir. 2004;20:11134. doi: 10.1021/la0492815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilar MR, Botelho do Rego AM, Ferraria AM, Jugnet Y, Nogués C, Peled D, Naaman R. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6957. doi: 10.1021/jp8008207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EA, Wanat MJ, Cheng Y, Barreira SVP, Frutos AG, Corn RM. Langmuir. 2001;17:2502. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herne T, Tarlov M. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8916. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomun T, Seitz H, Sturm H. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:11557. doi: 10.1021/jp905263x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love JC, Estroff LA, Kriebel JK, Nuzzo RG, Whitesides GM. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1103. doi: 10.1021/cr0300789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuzzo RG, Allara DL. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:4481. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois LH, Nuzzo RG. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1992;43:437. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahagi T, Nagai I, Ishitani A, Kuroda H, Nagasawa Y. J Appl Phys. 1988;64:3516. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodward JT, Walker ML, Meuse CW, Vanderah DJ, Poirier GE, Plant AL. Langmuir. 2000;16:5347. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai M, Lin J. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;238:259. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2001.7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirsaleh-Kohan N, Bass AD, Sanche L. Langmuir. 2010;26:6508. doi: 10.1021/la9039804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrovykh DY, Pérez-Dieste V, Opdah A, Kimura-Suda H, Sullivan JM, Tarlov MJ, Himpsel FJ, Whitman LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2. doi: 10.1021/ja052443e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Œmialek MA, Balog R, Jones NC, Field D, Mason NJ. Eur Phys J D. 2010;60:31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedhili N, Cloutier P, Bass AD, Madey TE, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:94704. doi: 10.1063/1.2338030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worley CG, Linton RW. J Vac Sci Technol A. 1995;13:2281. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Terrill RH, Tanzer TA, Bohn PW. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2654. [Google Scholar]

- 31.King DE. J Vac Sci Technol A. 1995;13:1247. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanche L. Induced Molecular Phenomena in Nucleic Acid. Vol. 19 Springer; The Netherlands: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsolais RM, Deschenes M, Sanche L. Rev Sci Instrum. 1989;60:2724. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagesha N, Gamache J, Bass AD, Sanche L. Rev Sci Instrum. 1997;68:3883. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klyachko DV, Huels MA, Sanche L. Radiat Res. 1999;151:177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denifl S, Ptasinska S, Cingel M, Matejcik S, Scheier P, Märk TD. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;377:74. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdoul-Carime H, Langer J, Huels MA, Illenberger E. Eur Phys J D. 2005;35:399. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubert D, Beikircher M, Denifl S, Zappa F, Matejcik S, Bacher A, Grill V, Märk TD, Scheier P. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:084304. doi: 10.1063/1.2336775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdoul-Carime H, Cloutier P, Sanche L. Radiat Res. 2001;155:625. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0625:leeesd]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ptasińska S, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:144713. doi: 10.1063/1.2338320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huels MA, Parenteau L, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 1994;100:3940. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malley TFO. Phys Rev. 1966;150:14. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanche L, Bass AD, Ayotte P, Fabrikant II. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;75:3568. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayotte P, Gamache J, Bass AD, Fabrikant II, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 1997;106:749. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu QB, Sanche L. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:2658. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bazin M, Ptasińska S, Bass AD, Sanche L. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:1610. doi: 10.1039/b814219j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akbulut M, Sack NJ, Madey TE. Surf Sci Rep. 1997;28:177. [Google Scholar]