SUMMARY

S. aureus over-produces a subset of immunomodulatory proteins known as the staphylococcal superantigen like proteins (Ssls) under conditions of pore-mediated membrane stress. In this study we demonstrate that overproduction of Ssls during membrane stress is due to the impaired activation of the two-component module of the quorum sensing Accessory gene regulator (Agr) system. Agr-dependent repression of ssl expression is indirect and mediated by the transcription factor Repressor of toxins (Rot). Surprisingly, we observed that Rot directly interacts with and activates the ssl promoters. The role of Agr and Rot as regulators of ssl expression was observed across several clinically relevant strains, suggesting that over-production of immunomodulatory proteins benefits agr-defective strains. In support of this notion, we demonstrate that Ssls contribute to the residual virulence of S. aureus lacking agr in a murine model of systemic infection. Altogether, these results suggest that S. aureus compensates for the inactivation of Agr by producing immunomodulatory exoproteins that could protect the bacterium from host-mediated clearance.

Keywords: MRSA, Staphylococcus aureus, quorum sensing, Ssls, TCS, Rot

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a highly versatile pathogen that can infect any tissue of the body and is responsible for approximately 292,000 hospitalizations in the United States each year with 19,000 resulting in death (Klevens et al., 2007). This has been compounded by the development of resistance to most of the antibiotics used against it, especially the beta-lactams and their derivatives, including methicillin. Although methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has been a problem in hospitals for many years, it has been an infrequent cause of infections among healthy individuals. However, in the past decade S. aureus infections have appeared in individuals who have had no prior contact with healthcare facilities. These strains are more virulent and transmissible than the MRSA, and are known as Community-Acquired (CA) MRSA (Graves et al., 2010).

S. aureus produces a large arsenal of virulence factors that play an important role during pathogenesis. These virulence factors include: adhesins, anti-oxidative stress factors, and a diverse array of secreted proteins (exoproteins), among others (Foster, 2005, Nizet, 2007). The S. aureus exoproteins are composed of cytotoxins, cytolytic peptides, enzymes with diverse substrate specificities, and immunomodulators. Among the immunomodulators, S. aureus produces a series of exoproteins known as staphylococcal superantigen-like proteins (Ssls) (Fraser & Proft, 2008). Ssls inhibit complement activation, bind to IgG and IgA, and inhibit neutrophil recruitment and function (Fraser & Proft, 2008). Importantly, Ssl over-production has been associated with S. aureus hyper-virulence in an animal model of systemic infection (Torres et al., 2007, Attia et al., 2010).

The S. aureus virulon is controlled by a complex regulatory network that involves a plethora of transcription factors and regulatory small RNA molecules (Novick, 2003, Cheung et al., 2004, Felden et al., 2011). Regulation of the staphylococcal virulon is further complicated by interactions among regulators as well as by post-transcriptional control (Novick & Geisinger, 2008, Felden et al., 2011, Olson et al., 2011). One of the most studied regulatory systems in S. aureus is the agr quorum-sensing system (Novick & Geisinger, 2008). agr is a complex locus consisting of two divergent transcription units driven by two promoters designated P2 and P3. The P2 transcript encodes a two-component signaling module, of which AgrC is the signal receptor and AgrA is the response regulator. Two additional proteins, AgrB and AgrD produce and secrete a thiolactone-containing autoinducing peptide (AIP), the activating ligand for AgrC (Novick & Geisinger, 2008, Thoendel et al., 2011). Agr activation is cell-density dependent and results in a switch from the production of surface-bound proteins to the production of secreted cytotoxins, superantigens, enzymes, and other virulence factors (Dunman et al., 2001, Queck et al., 2008). The P3 transcript encodes a 514 nucleotide regulatory RNA molecule termed RNAIII, which directly and indirectly controls the vast majority of agr target genes by its antisense function. The indirect regulation of virulence genes by RNAIII is mediated principally by post-transcriptional repression of the transcription factor known as Repressor of toxins (Rot) (Geisinger et al., 2006, Boisset et al., 2007). Rot is a member of the staphylococcal SarA family of transcription factors that represses genes coding for secreted proteins such as hemolytic toxins, enzymes, and enterotoxins (McNamara et al., 2000, Said-Salim et al., 2003, Cheung et al., 2004, Li & Cheung, 2008, Tseng & Stewart, 2005, Tseng et al., 2004) and activates the expression of genes encoding surface proteins such as protein A (SpA) and clumping factor B (Tegmark et al., 2000, Cheung et al., 2001, Said-Salim et al., 2003, Gao & Stewart, 2004).

S. aureus senses and responds to host molecules by altering the expression and production of its virulon. For example, it was demonstrated that S. aureus senses heme via a two-component system (TCS) designated the Heme Sensing System (Hss) (Torres et al., 2007, Stauff et al., 2007). Activation of the Hss by heme results in the expression of the heme-regulated transport system (HrtAB), an ABC transporter composed of an ATPase (HrtA) and a permease (HrtB), which are involved in heme-detoxification (Torres et al., 2007, Anzaldi & Skaar, 2010). Surprisingly, S. aureus lacking hrtA exhibit hyper-virulence in vivo (Torres et al., 2007). Hemin-exposed hrtA deficient strains undergo membrane stress due to the increased expression and production of HrtB, which, in the absence of HrtA, forms unregulated pores in the staphylococcal membrane (Attia et al., 2010). This pore-mediated stress results in the increased production of Ssls, which play a role in the hyper-virulence of hrtA deficient strains (Torres et al., 2007, Attia et al., 2010). Importantly, S. aureus exposed to gramicidin, a pore-forming antimicrobial peptide (AMP), exhibit an exoprotein profile similar to the hemin-exposed hrtA deficient strain and to that of wild type S. aureus over-producing HrtB (Attia et al., 2010).

In this report, we present evidence that membrane stress induced by the AMP gramicidin or unregulated HrtB interferes with the function of the Agr system, which results in the over-production of Ssls. Our data demonstrate that Agr represses ssls via RNAIII-dependent inhibition of rot. Furthermore, we provide evidence that Rot directly activates ssl promoters. The role of Agr and Rot as regulators of ssls was observed in a number of strains including naturally occurring agr-defective isolates. The significance of these findings are highlighted by the observation that overproduction of Ssls by an agr-defective strain plays a role in the residual virulence exhibited by this strain in a murine model of infection. Altogether, our data demonstrate that Rot acts as a direct activator of Ssls, which contribute to protecting agr defective S. aureus strains in vivo.

RESULTS

The exoprotein profiles of S. aureus strain Newman lacking agr resembles that of S. aureus cells undergoing pore-mediated membrane stress

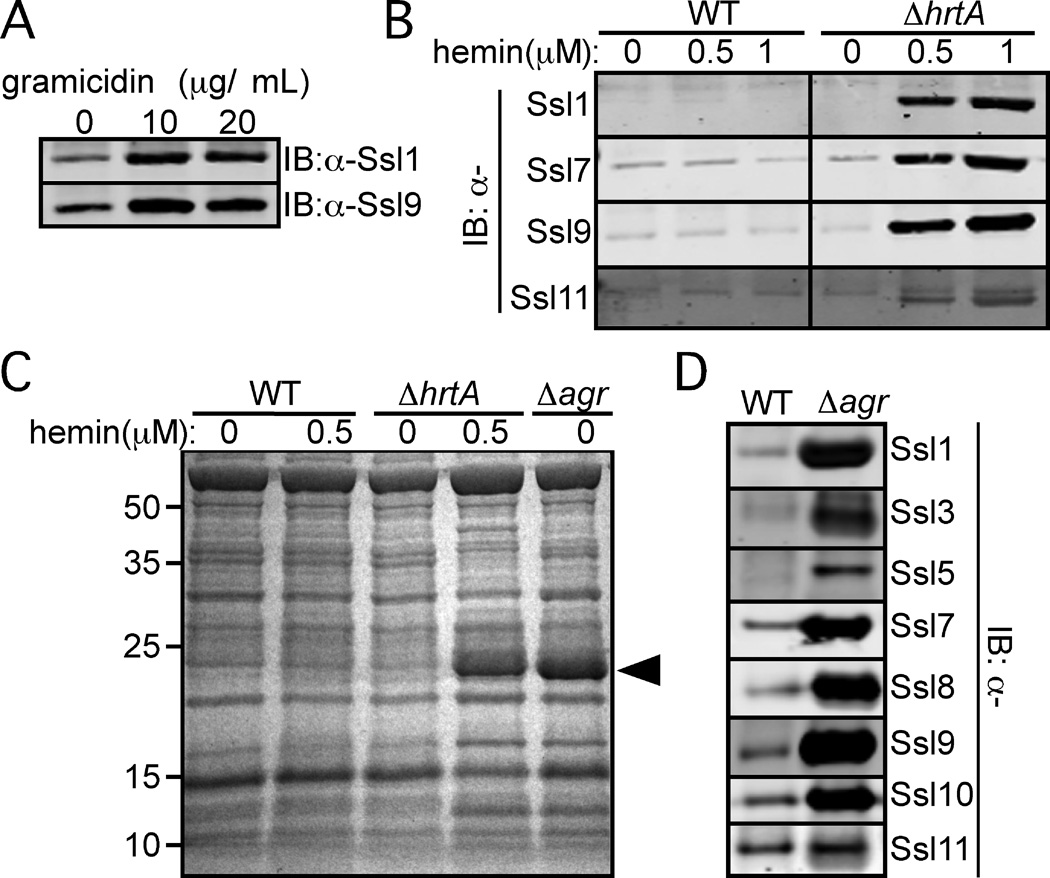

In S. aureus, induction of pore-mediated membrane stress either by exposure to the AMP gramicidin or HrtB overproduction (i.e., ∆hrtA mutant exposed to hemin) (Torres et al., 2007, Attia et al., 2010), results in the increased production of Ssls, a phenotype confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A–1B). We hypothesized that this membrane stress is likely perturbing the function of key regulatory systems located in the bacterial membrane. One such regulatory system involved in the expression of virulence factors is Agr (Novick & Geisinger, 2008). We observed that exoprotein profiles of S. aureus strain Newman undergoing membrane stress and an isogenic∆agr mutant were almost identical (Fig. 1C). One of the most striking differences between wild type (WT) and S. aureus either lacking agr or experiencing membrane stress is the induction of a band migrating at 25 kDa, which corresponds mostly to Ssls 1–11 (Torres et al., 2007, Attia et al., 2010). Consistent with this initial study, immunoblot analysis of exoproteins revealed that Ssls are indeed overproduced in the strain Newman lacking agr (Fig. 1D), suggesting that Agr inhibits Ssl production.

Fig. 1. agr inactivation results in the increased production of Ssls.

A) S. aureus strain Newman was grown to stationary phase in medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of gramicidin. Exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and indicated Ssls were detected by immunoblot. B) S. aureus strain Newman wildtype (WT) or the strain lacking hrtA (ΔhrtA) were grown to stationary phase in medium supplemented with hemin and the exoproteins were analyzed as in Panel A. C) Indicated strains were grown to stationary phase in medium with or without hemin. Exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. Arrowhead indicates Ssls 1–11. D) S. aureus strain Newman WT and an isogenic agr mutant strain were grown to stationary phase and the exoproteins were collected and processed as in Panel A.

Pore-mediated membrane stress affects quorum sensing

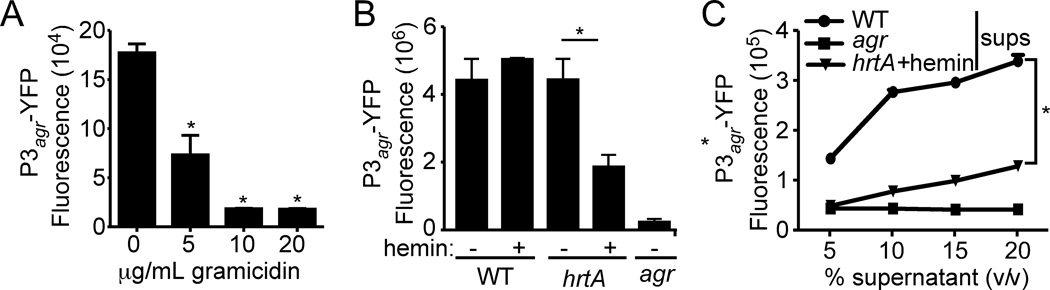

To begin dissecting the effect of membrane stress on the activation of Agr, we transformed S. aureus with a reporter plasmid wherein the expression of yellow fluorescent protein (yfp) is driven by the agr-P3 promoter (Yarwood et al., 2004), a direct target of AgrA (Novick & Geisinger, 2008). Exposure of S. aureus to sub-lethal concentrations of gramicidin resulted in a dose dependent reduction in fluorescence (Fig. 2A). Similarly, when exposed to hemin, the ∆hrtA mutant but not the WT strain, exhibited significant reduction in fluorescence compared to the wild type strain (Fig. 2B). Since Agr activation requires AIP, we also investigated the effect of membrane stress on AIP production by growing S. aureus containing the P3-yfp reporter in media supplemented with culture supernatants from WT, ∆agr, or membrane stressed cells (i.,e ∆hrtA mutant grown in medium supplemented with hemin). Supernatant from WT bacteria induced the activation of the reporter in a dose dependent manner, whereas supernatant from the ∆agr mutant did not activate the reporter (Fig. 2C). Additionally, supernatant from membrane stressed S. aureus were also unable to fully activate the RNAIII reporter (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these data suggest that pore-mediated membrane stress adversely affects Agr activation.

Fig. 2. Membrane stress affects the activation of Agr.

A) S. aureus strain Newman containing the P3agr-yfp reporter plasmid was grown to stationary phase in medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of gramicidin and the YFP fluorescence of normalized cultures (OD600) was measured. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− standard deviation (S.D.). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant difference compared to no gramicidin as determined by Student's t test (P≤0.05). B) S. aureus strain Newman WT, ΔhrtA, and the Δagr mutant strains containing the P3agr-yfp reporter were grown in media with or without 0.5 µM hemin, and fluorescence of normalized cultures (OD600) was measured at stationary phase. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− standard deviation (S.D.). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences as determined by Student's t test (P≤0.05). C) S. aureus strain Newman WT containing the P3agr-yfp reporter was grown in media to mid-log phase, washed extensively with PBS, and resuspended in media containing increasing concentrations of culture supernatants collected from stationary phase cultures of WT, Δagr, or ΔhrtA+2 µM hemin as the AIP source. Values represent average of three independent samples +/− standard deviation (S.D.). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences as determined by Student's t test (P≤0.05).

Agr inhibits Ssls production via RNAIII

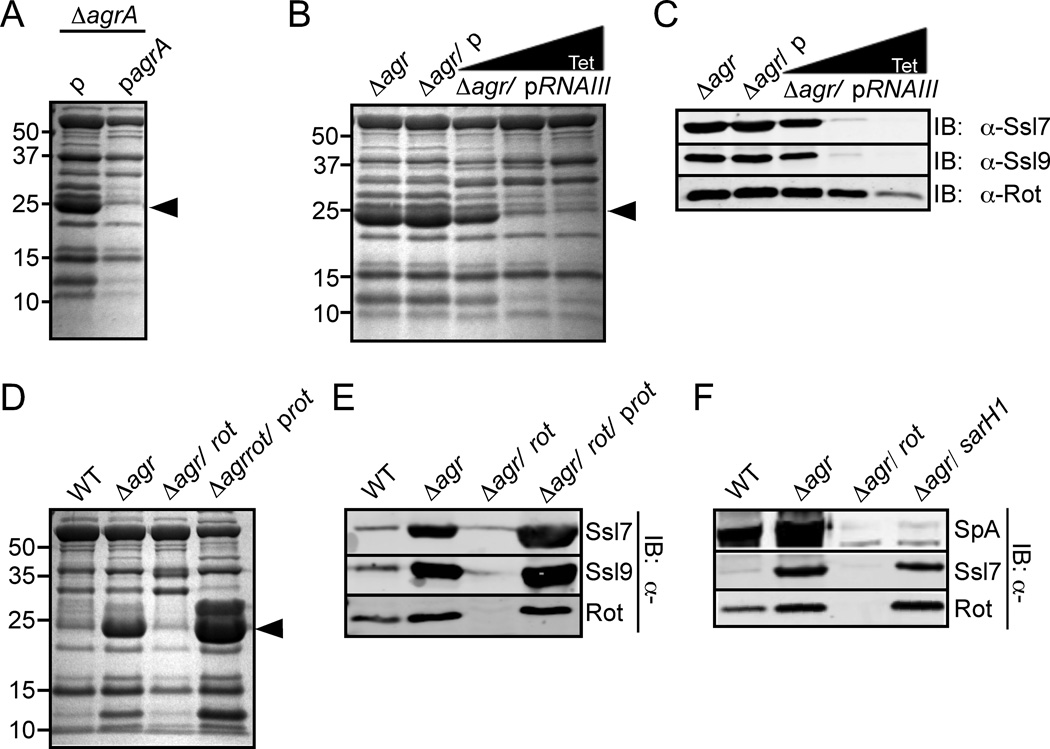

The Agr quorum sensing system regulates some genes directly by AgrA (Queck et al., 2008), however the vast majority of Agr target genes are regulated by RNAIII (Novick & Geisinger, 2008). Similar to the strain lacking the entire agr locus, a strain lacking only agrA also exhibited over-production of Ssls, a phenotype complemented by expressing agrA in trans (Fig. 3A). Because RNAIII expression is AgrA-dependent (Novick et al., 1995), we hypothesized that RNAIII or a target of RNAIII was directly involved in the Agr-mediated inhibition of Ssl production. To investigate the role of RNAIII in Ssl production, we transformed a plasmid containing a tetracycline-inducible RNAIII into the ∆agr mutant strain. Upon addition of increasing concentrations of tetracycline to the media, we observed a significant reduction of Ssls (Fig. 3B and 3C), suggesting that RNAIII is indeed involved in the inhibition of Ssl production.

Fig. 3. Rot is involved in ssl regulation.

A) S. aureus strain Newman lacking agrA was transformed with an empty plasmid (p) or an agrA complementation plasmid (pagrA). The strains were grown to stationary phase and the exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. Arrowhead indicates Ssls. B) S. aureus strain Newman lacking agr was transformed with a tetracycline-inducible RNAIII plasmid. The strain was grown in 0, 100, or 250 ng/mL tetracycline until it reached stationary phase. Exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. Arrowhead indicates Ssls. C) Exoproteins from Panel B were also transferred to nitrocellulose and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Ssl7 and Ssl9 antibodies. Proteins from whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-Rot antibody. D) Indicated S. aureus strains (Newman background) were grown to stationary phase and exoproteins processed and analyzed as in Panel B. E) Exoproteins from Panel D were also analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Ssl7 and Ssl9 antibodies. Proteins from whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-Rot antibody. F) Indicated S. aureus strains (Newman background) were grown to stationary phase and exoproteins were processed as in Panel A and immunoblotted with an anti-Ssl7 antibody, which detected Ssl7 and Protein A (SpA). Corresponding whole cell lysates were immunoblotted against Rot.

RNAIII modulates the expression of a number of genes via its translational repression of rot (Geisinger et al., 2006, Boisset et al., 2007). Consistent with this, we observed reduced Rot levels upon induction of RNAIII (Fig. 3C). To define the contribution of Rot to the over-production of Ssls exhibited by the ∆agr mutant strain, we generated a strain lacking both agr and rot. Comparison of the exoprotein profile of the ∆agr/rot double mutant strain to that of the strain lacking agr revealed that Rot is required for Ssl production, a phenotype complemented by expressing rot in trans in the double mutant strain (Fig. 3D and 3E).

Rot is required for the activation of ssl expression

Rot was originally identified as a repressor of virulence factors (McNamara et al., 2000), but it is now recognized that Rot also acts as an activator (Said-Salim et al., 2003). Rot induces the expression of spa, the gene that codes for Protein A, primarily by up-regulating the expression of sarH1, also known as sarS, a positive regulator of spa expression (Tegmark et al., 2000, Cheung et al., 2001, Gao & Stewart, 2004, Jelsbak et al., 2010). To determine if Rot regulates Ssl production via SarH1, we generated a S. aureus strain lacking both agr and sarH1 (agr/sarH1). As expected, immunoblot analysis revealed that both the ∆agr/rot and the ∆agr/sarH1 strains do not produce Protein A (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the ∆agr/sarH1 strain, but not the ∆agr/rot strain produced Ssls (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that Ssl production is regulated in a Rot-dependent, SarH1-independent manner.

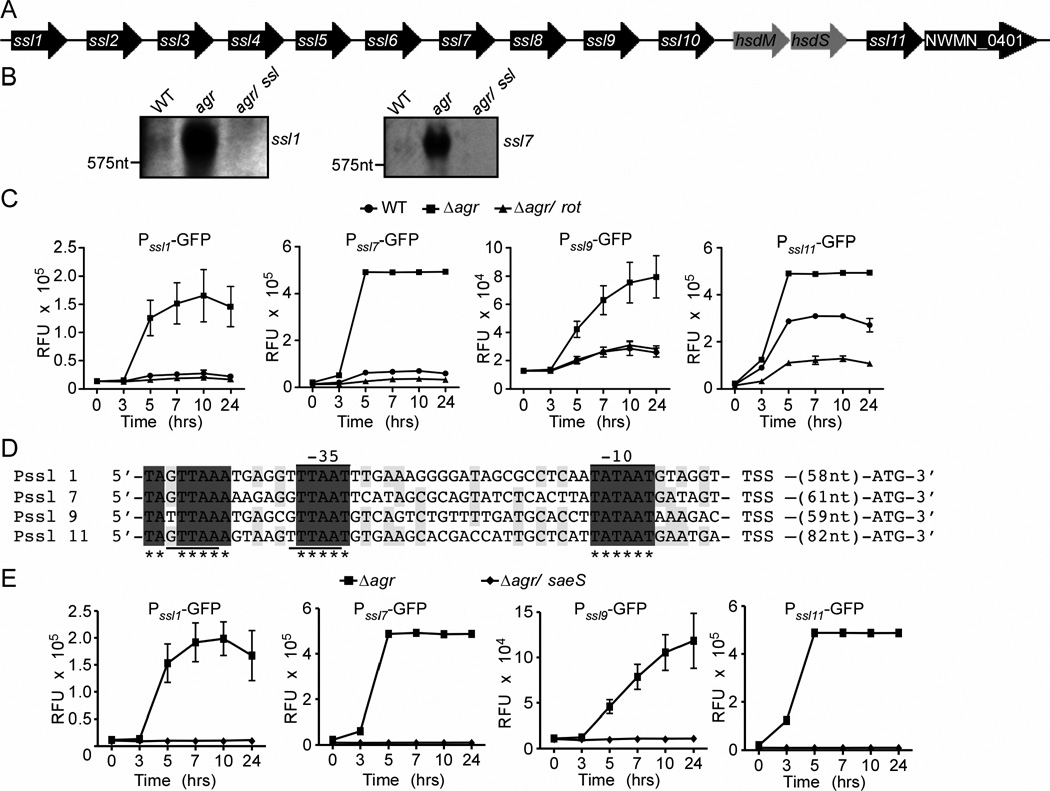

The ssl 1–11 genes are located in the pathogenicity island annotated as νSaα (Fig. 4A) (Baba et al., 2008). Each gene is separated by an intergenic region of DNA of more than 300 nucleotides, suggesting that the ssls are individually transcribed. Consistent with this supposition, operon prediction analysis suggests that most ssls are transcribed as monocistronic mRNA molecules (Wang et al., 2004). To validate this in-silico prediction, we performed Northern blot analyses with mRNA isolated from WT, ∆agr, and ∆agr/∆ssl. Our analyses revealed that ssl1 and ssl7 mRNAs are indeed produced as monocistronic messages and are induced in the ∆agr mutant strain (Fig. 4B). The increased transcription of ssls in the ∆agr mutant is consistent with the observation that Agr regulates the expression of ssl5 and ssl8 (Pantrangi et al., 2010).

Fig. 4. Rot influences the activation of the ssl promoters.

A) Schematic of the ssl locus in the S. aureus strain Newman chromosome. B) Northern blot analysis of ssl1 and 7 transcripts in 5 hour cultures of Newman WT, Δagr, and Δagr/ssl strains. C) Newman WT and the Δagr and Δagr/rot mutant strains were transformed with plasmids containing the indicated promoters driving gfp expression, and GFP fluorescence was monitored at the indicated time points. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− S.D. D) 5’-RACE products were sequenced to define the putative transcript start sites and upstream alignment revealed nucleic acids shared by all sequences (gray) and highly conserved between sequences (light gray). Putative −35 and −10 promoter regions are indicated. Underlined region indicates the SaeR consensus sequence. E) Newman lacking agr, saeS, and agr/saeS were transformed with plasmids containing the indicated promoters driving gfp expression, and GFP fluorescence was monitored at the indicated time points. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− S.D.

To directly determine if Rot influenced the expression of ssls, we monitored the activation of reporters where the promoters of selected ssls drive the expression of gfp. Measurement of GFP fluorescence revealed that in the ∆agr mutant, there was greater activation of the ssl promoters compared to WT (Fig. 4C), a phenotype dependent on Rot. Interestingly, in contrast to the ssl1, 7, and 9 promoters that exhibit low levels of activation in the WT strain, the ssl11 promoter is significantly activated in this strain (Fig. 4C). This differential activation could be due to properties of the ssl11 promoter that enhance Rot-mediated regulation of this promoter, as WT strains still produce low levels of Rot (Fig. 3E). This supposition is supported by the observation that the Δagr/rot mutant shows no activation of the ssl11 promoter (Fig. 4C).

Initial alignment of the ssl intergenic regions did not reveal any consensus sequence. To better characterize the ssl promoters, we performed 5’-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5’-RACE) employing mRNA isolated from the ∆agr mutant strain. To maintain consistency with our immunoblot data, we identified the 5’ ends of the ssl 1, 7, 9, and 11 mRNA transcripts (Fig. 4D). Alignment of these sequences revealed conserved −10 and −35 sites among the ssl promoters (Fig. 4D). Partially overlapping the −35 site we observed a perfect (ssl9 and ssl7) and imperfect (ssl1 and ssl11) binding sites for SaeR (GTTAAxxxxxxGTTAA; where x is any nucleotide) (Nygaard et al., 2010, Sun et al., 2010), the response regulator of the S. aureus exoprotein expression TCS (SaeRS; where SaeR is the response regulator and SaeS is the cognate histidine kinase) (Giraudo et al., 1994, Giraudo et al., 1999). The presence of SaeR binding sites in the ssl promoters is consistent with the observation that the SaeRS-TCS is required for ssl expression (Pantrangi et al., 2010). To investigate if Sae is also involved in the ssl over-expression phenotype observed with the Δagr mutant, we generated a strain lacking both agr and saeS (Δagr/sae) and monitored the activation of the ssl reporters. These experiments revealed that as with Rot, Sae is also required for the activation of the ssls in the Δagr mutant (Fig. 4E), suggesting that Rot and Sae work synergistically to coordinate the expression of ssls.

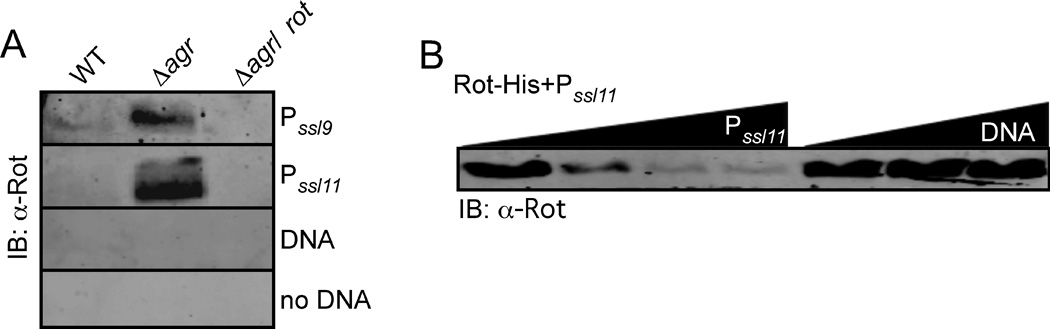

Rot directly binds to the ssl promoters

Our genetic data demonstrate that Rot influences the activation of the ssl promoters. To examine if Rot interacts with the ssl promoters, we employed a promoter pulldown assay. In this assay, DNA with ssl9 or 11 promoter sequences were biotinylated, bound to magnetic beads, and incubated with cytoplasmic lysates generated from S. aureus WT, ∆agr, and ∆agr/rot strains. Immunoblot analysis of captured proteins revealed that in lysates of the ∆agr mutant strain, which produces high levels of Rot, Rot was able to bind to the ssl9 and 11 promoters, but not to control DNA (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Rot binds to the ssl promoters.

A) Whole cell lysates from S. aureus strain Newman WT, Δagr, and the Δagr/rot double mutant grown to stationary phase were mixed with ssl9 promoter, ssl11 promoter, control DNA (DNA) conjugated to magnetic beads or beads alone. Captured proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted against Rot. B) Purified Rot was mixed with the ssl11 promoter conjugated to magnetic beads in the presence of increasing concentration of either unconjugated ssl11 promoter or control DNA (DNA) and Rot levels bound to the ssl11 promoter were detected by immunoblot as described in Panel A.

We next determined if Rot was able to bind to the ssl promoters in a direct and specific manner. We purified His-tagged Rot and performed a pulldown assay in the presence of increasing concentrations of non-biotinylated ssl11 promoter or control DNA. Non-biotinylated ssl11 promoter DNA, but not the control DNA, efficiently competed Rot off from the biotinylated ssl11 promoter (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that Rot was able to directly bind to the ssl11 promoter.

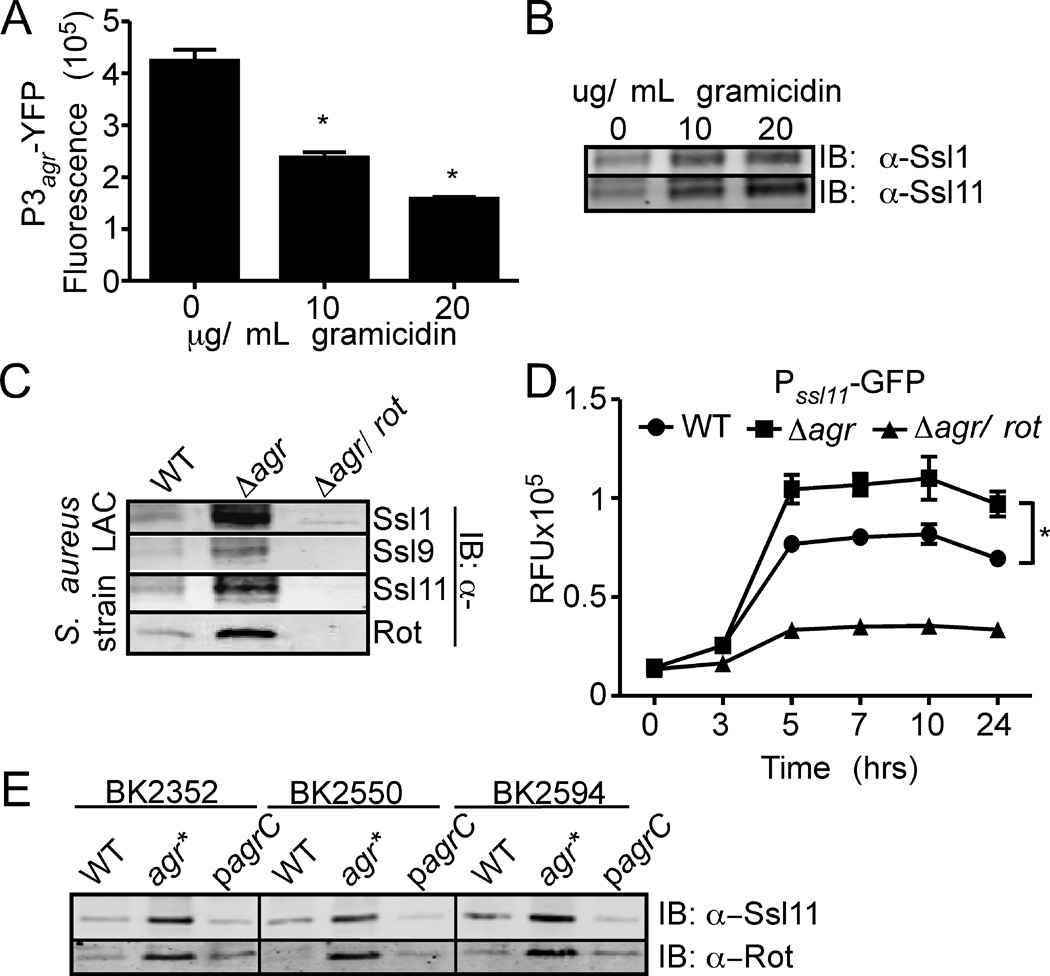

Naturally occurring agr-defective clinical isolates exhibit enhanced production of Ssls

To determine if the observations described here are conserved in other S. aureus strains, we first determined the affect of gramicidin on the activation of the Agr system in the CA-MRSA pulsed-field type USA300 strain LAC. As with strain Newman (Fig. 2A), we observed that gramicidin inhibited Agr activation in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 6A), a phenotype associated with increased Ssl production (Fig. 6B). To determine the influence of Agr and Rot on Ssl production in USA300, we generated ∆agr and ∆agr/rot isogenic LAC strains. Immunoblot analysis of exoproteins secreted by these strains revealed that Ssls were indeed overproduced in the ∆agr mutant compared to the WT parental strain, a phenotype dependent on Rot (Fig. 6C). In addition, we observed that Rot promotes activation of the ssl11 promoter in USA300 as observed in strain Newman (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. Ssls are over-produced by agr defective clinical isolates.

A) S. aureus USA300 containing the P3agr-yfp reporter plasmid was grown to stationary phase in medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of gramicidin and YFP fluorescence was measured. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− standard deviation (S.D.). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant difference compared to no gramicidin as determined by Student's t test (P≤0.05). B) USA300 WT was grown to stationary phase in media supplemented with indicated concentrations of gramicidin. Exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Ssl1 and Ssl11 antibodies. C) USA300 and the indicated isogenic mutants were grown to stationary phase and exoproteins were processed as in Panel B, and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Ssl 1, 9, and 11 antibodies. Corresponding whole cell lysates were immunoblotted against Rot. D) Strains described in Panel C were transformed with a plasmid containing the ssl11 promoter driving gfp expression, and GFP fluorescence was monitored at the indicated time points. Values represent average of three independent experiments +/− standard deviation (S.D.). Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant difference compared to no gramicidin as determined by Student's t test (P≤0.05). E) Parental clinical isolate strains (WT), the naturally occurring isogenic agr defective strain (agr*), and the corresponding complemented strain (pagrC) were grown to stationary phase. Exoproteins were prepared as in panel B and immunoblotted using an anti-Ssl11 antibody. Corresponding whole cell lysates were immunoblotted against Rot.

agr-defective strains are commonly found in patients with persistent infections, suggesting they could have an advantage in certain in vivo scenarios (Traber et al., 2008, Fowler et al., 2004, Vuong et al., 2004, Shopsin et al., 2010). We therefore sought to test whether Ssls are over-produced among clinical agr-defective strains, using a collection of genotypically diverse agr-defective MSSA and MRSA clones obtained from mixed cultures containing agr+ parental strains (Shopsin et al., 1999, Shopsin et al., 2000, Shopsin et al., 2008, Shopsin et al., 2010). All strains were previously typed to confirm that variants within a single specimen were genotypically isogenic (Table 1). Consistent with previous reports, the basis of agr-dysfunction in the agr-defective component of the mixtures could be traced to inactivating mutations in agrA or agrC (Table 1) (Shopsin et al., 2010). All agr-defective strains were found to over-produce Ssls in comparison to their WT counterparts, a phenotype associated with increased levels of Rot (Fig. 6E and Table 1). Additionally, complementation with an agrC-containing plasmid confirmed that the Ssl overproduction was agr-dependent (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that increased Ssl production is a feature of clinical as well as laboratory derived agr-defective S. aureus clones.

Table 1.

Characteristics of clinical agr-defective S. aureus from agr (+) and agr (−) mixtures

| Strain | Antibiotic susceptibility |

Ssla | Source |

spa typeb |

spa motif | CCc |

agr group |

Mutationd | Predicted result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS188 | MRSA | + | BAL | 15 | A2-A1-K1-E1-E1- M1-B1-K1-B1 |

45 | 1 | 125–126 (+1 bp) |

Frameshift - truncated AgrC |

| BK3393 (19552)f | MSSA | + | nares | 62 | A2-A1-K1-E1-M1- B1-K1-B1 |

45 | 1 | t190C | Pro>Ser at aa 64 in AgrC |

| BK2352 (121b) | MRSA | + | sputum | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | 286–288 (−3 bp) |

Ser STOP at aa in 96 AgrC |

| BK2439 | MRSA | + | sputum | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | c652t | Arg>STOP at aa 218 in AgrA |

| BK2550 | MRSA | + | urine | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | t161g | Leu>Arg at aa 54 in AgrC |

| BK2563 | MRSA | + | wound | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | 315–360 (−45 bp) |

Frameshift - truncated AgrA |

| BK2568 | MRSA | + | blood | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | t325a t328c c332t |

TyrSerThr->AsnProIle at aa 109– 111 in AgrC |

| BK2574 | MRSA | + | sputum | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | a716 (−1 bp) |

Frameshift - truncated AgrA |

| BK2575 | MRSA | + | sputum | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | 2080287- IS1181 |

Frameshift - truncated AgrC |

| BK2594 | MRSA | + | sputum | 2 | T1-J1-M1-B1-M1- D1-M1-G1-M1-K1 |

5 | 2 | a562c | Thr>Pro at aa 188 in AgrC |

| BS237 | MRSA | + | sputum | 3 | W1-G1-K1-A1- O1-M1-Q1 |

30 | 1 | g616t | Glu>STOP at aa 206 in AgrC |

| BK4910 (19570)e | MSSA | + | nares | 93 | X1-K1-B1 | 47 | 1 | 95–104 (−10 bp) |

Frameshift - truncated AgrA |

| BK4645 (19566)e | MSSA | + | nares | 1 | Y1-H1-G1-F1-M1- B1-Q1-B1-L1-O1 |

8 | 1 | 425–426 (+1 bp) |

Frameshift - truncated AgrC |

Ssl over-production in the isogenic agr defective based on immunoblot against Ssl1 and Ssl9.

spa typing uses sequence repeats in the spa gene to determine the evolutionary relatedness of S. aureus isolates (Shopsin et al., 1999).

spa-type deduced clonal complex (CC). Isolates broadly grouped according to their evolutionary relatedness (Cooper & Fiel., 2006).

Designation corresponds to the region in agrA or agrC of genome sequenced isolates of the same agr group.

Colonizing isolates.

NOTES: BAL, bronchioalveolar lavage.

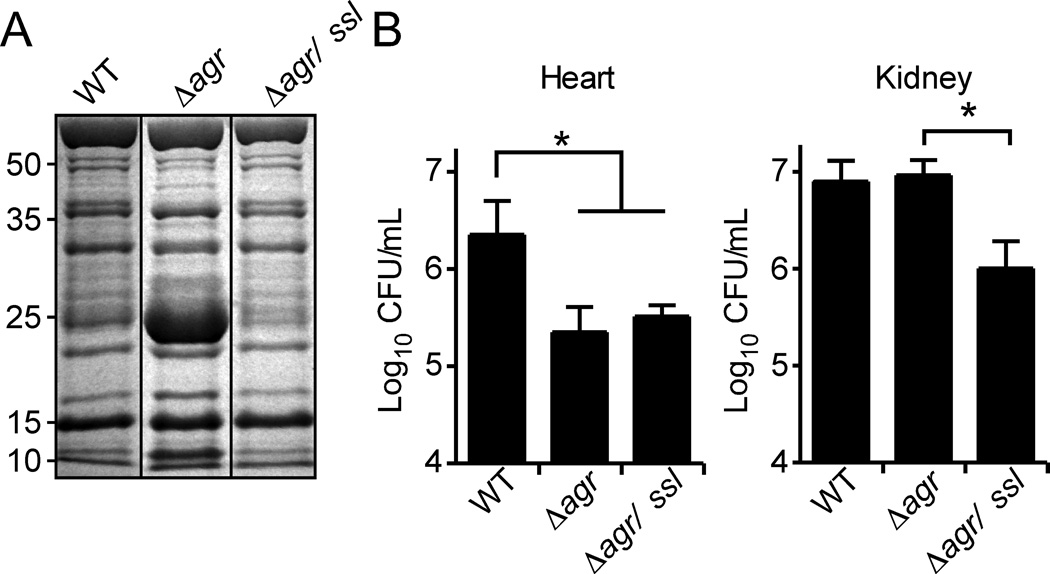

Ssls contributes to the pathogenesis of agr defective S. aureus

To define the potential contribution of Ssls to the pathogenesis of agr-defective strains we constructed a ∆agr mutant strain lacking ssls 1–11. Analysis of the exoprotein profile of this strain revealed that the ∆agr/∆ssl1–11 strain lacked the ~25-kDa Ssls band (Fig. 7A). To measure the virulence of these strains, we employed a mouse model of systemic infection that results in the formation of abscesses in the kidney, heart, and liver (Skaar et al., 2004, Corbin et al., 2008, Torres et al., 2007, Pishchany et al., 2010). Mice were infected retro-orbitally with 1 × 107 CFU of S. aureus Newman WT, ∆agr, or the ∆agr/∆ssl 1–11 mutant strain. Consistent with the important role of the Agr system in staphylococcal pathogenesis (Booth et al., 1995, Cheung et al., 1994, McNamara & Bayer, 2005, Peterson et al., 2008, Rothfork et al., 2004, Bubeck Wardenburg et al., 2007, Wright et al., 2005), animals infected with the S. aureus strain Newman lacking agr or agr/ssl1–11 did not succumb to infection (data not shown). Enumeration of bacteria four days after infection revealed a 1 log reduction in bacteria burden in the hearts of animals infected with the strain lacking agr and agr/ssl1–11 compared to the bacterial burden observed in animals infected with the WT strain (Fig. 7B). In contrast, enumeration of bacteria from kidneys four days after infection revealed no difference in the bacterial burden between WT and ∆agr, consistent with the observation that agr-defective strains are attenuated but not avirulent (Fig. 7B) (Cheung et al., 1994, Gillaspy et al., 1995, McNamara & Bayer, 2005, Kielian et al., 2001). Of note, we observed a significant reduction in the bacterial burden of ∆agr/∆ssl1–11 compared to that of the ∆agr strain (P < 0.0053) (Fig. 7B), suggesting that Ssls contribute to the kidney-specific infection of agr mutant strains.

Fig. 7. Disruption of ssls 1–11 reduced the bacterial burden of an agr mutant in vivo.

A) S. aureus strain Newman WT, Δagr mutant, and the Δagr/ssl 1–11 double mutant were grown to stationary phase and the exoproteins were collected, precipitated, separated using SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. B) 10 mice each were systemically infected with 107 CFU/mL of indicated strains. After four days, mice were sacrificed and bacterial burden determined by enumeration of CFUs in the hearts and kidneys. Asterisk (*) denotes statistical significance determined by Student’s t test (P≤0.05).

DISCUSSION

We report here that S. aureus regulates ssl expression via Rot. Genetic and biochemical experiments demonstrate that Rot regulates the expression of ssls by binding to and activating the ssl promoters. To our knowledge this is the first demonstration of genes that are directly activated by Rot, a potent repressor of toxin expression. The pathophysiological relevance of our findings is highlighted by the observation that Ssls over-produced by a strain lacking agr contribute to the ability of this strain to infect renal tissue in a murine model of systemic infection and by the observation that clinical isolates harboring agr inactivating mutations also over-produce Ssls. Conversely, the Ssls seem to play no role in the ability of the Δagr mutant to infect cardiac tissue, suggesting that other Agr-regulated factor(s) is responsible for this phenotype.

This study also adds to our understanding of how S. aureus responds to potential stressors encountered during infection. Our data demonstrate that pore-mediated membrane stress inhibits agr function, phenocopying inactivating agr mutations. The mechanism by which pores inhibit Agr function is not completely understood. Since Agr signaling depends on a series of membrane-associated proteins, we believe that the effect of pores on Agr signaling could be multifactorial. For example, pores may affect: (i) AgrC-AgrA signal transduction, (ii) membrane anchoring of AgrD, (iii) AgrB function, and/or (iv) localization/function of signal peptidases involved in AIP processing (Thoendel et al., 2011, Novick & Geisinger, 2008). Currently, we know that pore-mediated membrane stress reduces AIP levels in the culture supernatant. This finding explains the decreased activation of the agr-P3 promoter seen in our study. Additional biochemical work is needed to dissect the exact molecular mechanism of pore-mediated inhibition of Agr signaling.

A surprising finding from this work is the identification of Rot as a positive and direct regulator of ssl expression. Rot was initially identified in a transposon screen, where its inactivation partially restored alpha toxin and protease production in a ∆agr mutant strain (McNamara et al., 2000). Microarray analysis comparing the transcriptome of ∆agr mutant to that of an ∆agr/rot double mutant revealed that Rot positively and negatively influences a large number of genes (Said-Salim et al., 2003). A striking pattern of Rot-regulated factors is that, in general, genes up regulated by Rot are those that code for surface proteins and the genes down regulated by Rot are those that code for exoproteins. Thus, the gene products positively regulated by Rot are thought to be involved in the establishment and early stages of infection by the bacteria, while the down regulated gene products are thought to be involved in dissemination and nutrient acquisition. This study introduces ssls as a new subset of genes positively regulated by Rot, suggesting that S. aureus concomitantly up-regulates cell surface proteins and Ssls, which combine will enable S. aureus to adhere to tissues and inhibit opsonization and immune cell recruitment.

Rot production is primarily regulated by RNAIII (Boisset et al., 2007, Geisinger et al., 2006). In addition, S. aureus also regulates rot at the transcriptional level where SarA and SarS/H1 seem to repress rot expression (Manna & Ray, 2007, Hsieh et al., 2008) and the TCS GraRS and ArlRS seem to activate rot expression (Herbert et al., 2007, Liang et al., 2005). In addition, data from the Staphylococcus aureus microarray meta-database (SAMMD) (Nagarajan & Elasri, 2007) suggest that rot is repressed under several stress conditions (cold shock, SOS response, and acid response) and upon exposure to fusidic acid and ciprofloxacin (Nagarajan & Elasri, 2007, Weinrick et al., 2004, Anderson et al., 2006, Cirz et al., 2007, Delgado et al., 2008). The complex regulatory schemes for rot expression correlate with the observation that Rot levels vary greatly among different strains of S. aureus (Jelsbak et al., 2010). Thus, Rot-mediated regulation of ssls could also be impacted by additional regulators as well as different environments.

The molecular mechanism of how Rot regulates target promoters is not well characterized. Promoter fusion assays have demonstrated that Rot influences the promoter activity of enterotoxin A, enterotoxin B, itself, sae, and alpha toxin (Tseng et al., 2004, Li & Cheung, 2008). Purified Rot have been demonstrated to directly interact with the enterotoxin B promoter (Tseng & Stewart, 2005). In addition, promoter pulldown analyses have indicated that Rot binds to the promoters of the proteases and protein A (Oscarsson et al., 2005, Oscarsson et al., 2006). While Rot has been implicated in the directly regulation of gene expression, no consensus Rot binding site has been elucidated. In this report we present direct evidence that Rot regulates the expression of ssls by activating their promoters when Agr is turned off. While our data demonstrate that Rot acts as an activator of the ssls promoters, it is still unclear how Rot is able to repress the expression of certain genes (e.g., toxins) while activating others (e.g., ssl). It could be possible that Rot interacts with additional transcription factors in order to carry out its differential regulation. Consistent with this supposition, it was recently demonstrated that mutations on saeRS and sigB also altered ssls expression (Pantrangi et al., 2010). The potential role of the Sae TCS in the regulation of ssls is consistent with our observation that the SaeR binding site overlaps with the −35 region of the ssl promoters and that Sae and Rot are both required for the activation of the ssl promoters. The molecular mechanism by which Rot collaborates with SaeR to regulate the expression of ssls remains to be elucidated and is an area of current investigation in our laboratory.

Ssls are a fascinating group of exoproteins that share sequence similarity to superantigens but, unlike superantigens, are not mitogenic to T-cells and do not bind MHC class II molecules (Fraser & Proft, 2008). The Ssls have a conserved two-domain structure, but the function and action of each Ssl appears to be different. Ssls 5 and 11 inhibit neutrophil activation and recruitment (Bestebroer et al., 2009, Bestebroer et al., 2007, Chung et al., 2007); Ssls 7 and 10 bind IgA and IgG (Langley et al., 2005, Wines et al., 2006, Itoh et al., 2010) and also inhibit complement activation (Itoh et al., 2010, Bestebroer et al., 2010, Fraser & Proft, 2008, Langley et al., 2005). The combined role of Ssls in S. aureus pathogenesis is less clear, primarily because most of the studies investigating the function of these molecules have been performed in vitro with purified proteins.

Our data demonstrate that in contrast to most staphylococcal secreted proteins, which require Agr for their production, the production of Ssls are inhibited by Agr. Thus, Ssls may have evolved to protect S. aureus in conditions/environments where Agr is not fully functional. Transient inhibition of Agr can occur in vivo without the occurrence of a genetic mutation. For example, serum inhibits Agr activation (Yarwood et al., 2002), likely due to apolipoprotein B, which inhibits AIP-AgrC interaction (Peterson et al., 2008). In addition, AIP-1 can be inactivated by oxidation in phagocytes, resulting in the inhibition of Agr (Rothfork et al., 2004). Importantly, S. aureus up-regulates ssls when exposed to neutrophils (Voyich et al., 2005), as well as when exposed to neutrophil antimicrobial products (Palazzolo-Ballance et al., 2008). The importance of Ssls in S. aureus pathogenesis is supported by our finding that a strain lacking agr and ssls1–11 exhibited significant reduction in bacterial burden compared to the parental Δagr mutant strain. Thus, S. aureus may compensate for defects and/or transient inhibition of Agr by increasing the production of Rot, which in turn coordinates the production of Ssls that could play a key role in protecting the bacterium from clearance by the immune system.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The S. aureus strains used in this study are described in Table 2. S. aureus were grown on tryptic soy broth (TSB) solidified with 1.5% agar at 37°C or in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) supplemented with 1% CAS amino acids (RPMI/CAS) with shaking at 180 rpm, unless otherwise indicated. When appropriate, TSB and RPMI/CAS were supplemented with chloramphenicol at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml, erythromycin at 10 µg/mL or tetracycline at 4 µg/mL. Escherichia coli were grown in Luria broth (LB) and when needed, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin at a final concentration of 100 µg/mL.

Table 2.

Staphylococcus aureus strains

| Strain | Background | Description | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VJT 1.01 | Newman | Wildtype (agr+) | wildtype | (Duthie & Lorenz, 1952) |

| VJT 7.17 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of agr::tet from RN7206 into VJT 1.01 | agr::tet | this study |

| VJT 9.98 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of rot::Tn917 from RN10623 into VJT 1.01 | rot::Tn917 | this study |

| VJT 10.03 | VJT 7.17 | Transduction of rot::Tn917 from RN10623in to VJT 7.17 | agr::tet rot::Tn917 | this study |

| VJT 2.57 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of agrA::Tn551 from RN6112 into VJT 1.01 | agrA::Tn551 | this study |

| VJT 1.06 | VJT 1.01 | Clean deletion of hrtA | ΔhrtA | (Torres et al., 2007) |

| VJT 10.56 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of sarH1::Tn551 from RN9537 into VJT 1.01 | sarH1::Tn551 | this study |

| VJT 10.58 | VJT 7.17 | Transduction of sarH1::Tn551 from RN9537 into VJT 7.17 | sarH1::Tn551 agr::tet | this study |

| VJT 9.58 | VJT 1.01 | Clean deletion of the ssl1–11 locus | Δssl1–11 | (Attia et al., 2010) |

| VJT 9.94 | VJT 9.58 | Transduction of agr::tet from RN7206 into VJT 9.58 | Δssl1–11 agr::tet | this study |

| RN4220 | 8325-4 | Restriction deficient cloning host | (Kreiswirth et al., 1983) | |

| AH1263 | USA300 LAC | Erythromycin sensitive clone | wildtype | (Boles et al., 2010) |

| AH1292 | USA300 LAC | Transduction of agr::tet from RN7208 into AH1263 | agr::tet | this study |

| VJT 16.37 | AH1292 | Transduction of rot::Tn917 from RN10623 into AH 1292 | agr::tet rot::Tn917 | this study |

| HF6131 | RN6734 | Transduction of saeS:: bursa | saeS :: bursa | (Adhikari & Novick, 2008) |

| VJT12.22 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of saeS::bursa from HF6131 | saeS::bursa | this study |

| VJT 17.25 | VJT 1.01 | Transduction of agr::tet from RN7206 into VJT 12.22 | agr::tet saeS::bursa | this study |

Construction of mutants

Strains used in this study are described in Table 2. The S. aureus Newman derivative lacking hrtA and ssl1–11 were described previously (Torres et al., 2007, Attia et al., 2010). S. aureus mutants lacking the agr locus, agrA, rot, saeS and sarH1 were constructed by transduction using the phage 80α (Novick, 1990).

Plasmids

Primers and plasmids used in this study are described in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Primers

| # | Name | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 311 | rot-6xHis-3'-RXho | 5’-CCCCTCGAGTTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGCACAGCAATAATTGCGTTTA | complementation vector |

| 313 | rot5'F-NdeI | 5’-CCCCCATATGAAAAAAGTAAATAACGACACTG | complementation vector |

| 261 | NdeI-F-agrA | 5’-CCCCCATATGAAAATTTTCATTTGCGAAGAC | complementation vector |

| 262 | Xho-STOP-R-agrA | 5’-CCCCTCGAGTTATATTTTTTTAACGTTTCTCACC | complementation vector |

| 336 | pssl1-F-PstI | 5’-CCCCCTGCAGGACGCGTTTTAGTTGATGTG | reporter vector |

| 314 | pssl1-R-no RBS-KpnI | 5'-CCCCGGTACCCTATTTAAATTTGATTTTTCAATTACG | reporter vector |

| 341 | pssl7-F-PstI | 5’-CCCCCTGCAGGCAGACTAGTAATTGTAGGG | reporter vector |

| 319 | pssl6/7-R-no RBS-KpnI | 5'-CCCCGGTACCCTATTTATAAATTTTGTCTTAATATATT | reporter vector |

| 343 | pssl9-F-PstI | 5’-CCCCCTGCAGGAATGAAAGCTTAAGAAGCGG | reporter vector |

| 321 | pssl9-R-no RBS-KpnI | 5'-CCCCGGTACCCTTAATGTATTGGATTGTTATTATTA | reporter vector |

| 345 | pssl11-F-PstI | 5’-CCCCCTGCAGTTAGGCACTGTGAAAGCGC | reporter vector |

| 323 | pssl11-R-no RBS-KpnI | 5'-CCCCGGTACCTTTTAGTCTATTTGATTTATTCTATTA | reporter vector |

| 348 | sGFP-R-EcoRI | 5'-CCCGAATTCTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGG | reporter vector |

| 347 | sGFP-F-PstI | 5'-CCCCTGCAGCTGATATTTTTGACTAAACCAAATG | reporter vector |

| 43 | SACOL0473 (ssl9)-P-F | 5’-CCCCGAATTCGAATGAAAGCTTAAGAAGCGG | promoter pull-down |

| 304 | p-ssl9-R-Bio | 5’-BIO-CCCCATTTTTTTGCTCCAATCTTAATG | promoter pull-down |

| 156 | p-set11 5' EcoR1 | 5’-CCCCGAATTCTTAGGCACTGTGAAAGCGC | promoter pull-down |

| 308 | p-ssl11-R-BIO | 5’-BIO-CCCCAATTCTATGCTCCCAATTTTTAG | promoter pull-down |

| 87 | SACOL2004-P-F-EcoRI | 5’-CCCCGAATTCAAAGAAGGATAATATTGAAAGG | promoter pull-down |

| 82 | SACOL2004_R_bio | 5’-BIO-AATCACTTTCTTTCTATTTAATTTT | promoter pull-down |

| 82 | MJT82 | 5'-GTTGTTGAATTCTTCATTACAAAAAAGGCCGCGAGCTTGGGA | reporter vector |

| 85 | MJT85 | 5'-GTTGTTGGTACCAGATCACAGAGATGTGATGGAAAATAGTTG | reporter vector |

| 575 | ssl1-cDNA | 5'-ACTCTGATTCACTTTGTTG | 5'-RACE |

| 576 | ssl1-PCR | 5'-TTTTGCTATCGCTTTAAATTTCATAAT | 5'-RACE |

| 577 | ssl7-cDNA | 5'-AATGTTGTACTCTCTCTTG | 5'-RACE |

| 578 | ssl7-PCR | 5'-TTAGCTAACGTTTTTAATTTCACAGT | 5'-RACE |

| 579 | ssl9-cDNA | 5'-TTGCGTTGTGTCTCATCAA | 5'-RACE |

| 580 | ssl9-PCR | 5'-TTTAGCTATCGTTGTTAATTTCATATT | 5'-RACE |

| 581 | ssl11-cDNA | 5'-TAGCTTGTGATCTAACCT | 5'-RACE |

| 582 | ssl11-PCR | 5'-GCTTTAGCAATATTTTTTAATTTCATAAT | 5'-RACE |

| 408 | Ssl1-F | 5'-ATGAAATTTAAAGCGATAGCAAAAG | Northern |

| 409 | Ssl1-R | 5'-TTATTTCATTTCTACTAGAATTTTATTA | Northern |

| 410 | Ssl7-F | 5'-GTGAAATTAAAAACGTTAGCTAAAG | Northern |

| 411 | Ssl7-R | 5'- AATTTGTTTCAAAGTCACTTCAATC | Northern |

| 1 | Orf5 5' | 5'-ATGCTGAAGTAGATGTAGTCG | agr amplification/sequencing |

| 2 | hld 3' B | 5'- AAGACC TGC ATC CCT AAA CG | agr sequencing |

| 3 | agr C2 | 5'-CTTGCGCATTTCGTTGTTGA | agr sequencing |

| 4 | agrB 5 | 5'- AAT AAA ATT GAC CAG TTT GC | agr sequencing |

| 5 | agr B1 | 5'-TATGCTCCTGCAGCAACTAA | agr sequencing |

| 6 | PAN R | 5'-GAATAATACCAATACTGCGAC | agr sequencing |

| 7 | agrC 5'B | 5'- AAAGAGATGAAATACAAACG | agr sequencing |

| 8 | agrA 3' A | 5'-ATACACTGAATTACTGCCACG | agr sequencing |

| 9 | agr A 5' A | 5'- ATTAACAACTAGCCATAAGG | agr sequencing |

| 10 | agr2-R | 5'-GCAATCGCGTTGCTGCAATAGT | agr amplification/sequencing |

Table 4.

Plasmids

| Name | Description | Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pOS1 | empty vector control | Cm | (Schneewind et al., 1992) |

| pOS1sGFP-Pssl1sodRBS | ssl1 promoter and sod RBS driving sgfp expression | Cm | this study |

| pOS1sGFP-Pssl7sodRBS | ssl7 promoter and sod RBS driving sgfp expression | Cm | this study |

| pOS1sGFP-Pssl9sodRBS | ssl9 promoter and sod RBS driving sgfp expression | Cm | this study |

| pOS1sGFP-Pssl11sodRBS | ssl11 promoter and sod RBS driving sgfp expression | Cm | this study |

| pOS1sGFP promoterless | pOS1 containing sgfp with no promoter | Cm | this study |

| pOS1-Plgt | lgt promoter in an empty vector | Cm | (Bubeck Wardenburg et al., 2006) |

| pOS1-Plgt-agrA | lgt promoter driving agrA expression | Cm | this study |

| pOS1-Plgt-rotxHis | lgt promoter driving rot with a 6xHis tag | Cm | this study |

| pDB59-P3agr-yfp | agr P3 promoter driving yfp expression | Cm | (Yarwood et al., 2004) |

| pCM11 | vector containing sgfp with sarA promoter and sod RBS | Erm | (Lauderdale et al., 2010) |

| pALC2073_RNAIII | rnaIII under tetracycline-inducible promoter | Cm | This study |

| pEG29 | agr P2 promoter driving agrC cloned from RN6607 (agrII) | Cm | (Geisinger et al., 2009) |

Complementation plasmids

For the construction of a plasmid constitutively expressing His-tagged Rot, a PCR amplicon was made containing the rot ORF (NWMN_1655) into which sequence coding for six histidines were inserted at the 3’ end just prior to the stop codon using the primers 311 and 313 (Table 2). The PCR product was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector pOS1-Plgt (Bubeck Wardenburg et al., 2006), which had been digested with the same restriction enzymes. Ligation product was then transformed into E. coli DH5α and the resulting plasmid was designated pOS1-Plgt-rotxHis. The plasmid was transformed into the restriction-deficient S. aureus RN4220 followed by electroporation into the respective S. aureus strains.

For the construction of a plasmid constitutively expressing AgrA, a PCR amplicon was made containing the agrA ORF (NWMN_1946) using the primers 261 and 262 from Table 2. The PCR product was then digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into pOS1-Plgt, which had been digested with the same restriction enzymes. Ligation mixtures were then transformed into E. coli DH5α and the resulting plasmid was designated pOS1-Plgt-agrA. The plasmid was transformed into the restriction-deficient modification-positive S. aureus RN4220 followed by transformation into the respective electrocompetent S. aureus strains.

Generation of reporter plasmids

The gfp coding sequence with the sarA promoter and sod RBS was amplified from pCM11 (Lauderdale et al., 2009) using primers 348 and 347 from Table 2. The amplicon was digested with EcoRI and PstI and ligated into the pOS1 vector (Schneewind et al., 1992), which had been digested with the same restriction enzymes. The ligation mixture was then transformed into E. coli DH5α and the resulting plasmid was designated pOS1sGFP. The putative promoter regions of ssl1, 7, 9 and 11 were amplified with primers 336 and 314, 341 and 319, 343 and 321, 345 and 323 respectively. The PCR amplicons were digested with PstI and KpnI and ligated into the pOS1sGFP vector, which had been digested with the same restriction enzymes to remove the sarA promoter. The ligation mixtures were transformed into E. coli DH5α and the resulting plasmids were designated pOS1-Pssl1sod RBS-sGFP, pOS1-Pssl7sod RBS-sGFP, pOS1-Pssl9sod RBS-sGFP, pOS1-Pssl11sod RBS-sGFP. The plasmids were transformed into the restriction-deficient modification-positive S. aureus RN4220 followed by transformation into the respective electrocompetent S. aureus strains using the protocol described.

Generation of tetracycline inducible RNAIII

The RNAIII tetracycline-inducible expression plasmid was constructed by PCR amplifying the RNAIII region from chromosomal DNA of S. aureus strain SH1000 using primers 82 and 85 from Table 3. The PCR amplicons was then digested with KpnI and EcoRI and ligated into pALC2084 (Bateman et al., 2001) plasmid that had been digested with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmid was designated pALC2073_RNAIII.

Exoprotein profiles

Exoproteins were produced and processed as described before (Torres et al., 2010, Attia et al., 2010). Briefly, S. aureus strains were grown in 5 mL RPMI/CAS overnight at 37°C with shaking at 180 rpm. The overnight cultures were then diluted 1:100 into a new 5 mL culture in a 15 mL conical tube. Cultures were grown to stationary phase and then normalized to the same optical density (OD600). Bacterial cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 400×g for 15 minutes and proteins in the culture supernatant were precipitated using 10% (v/v) TCA at 4°C overnight. The precipitated proteins were sedimented by centrifugation, washed, dried, resuspended in 1× SDS laemmli buffer and boiled for 10 minutes. Proteins were separated using 15% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue.

RNA preparation

S. aureus cultures were grown in RPMI/CAS with the appropriate additive for six hours (stationary phase) and then normalized to the same OD600 (~1.433). Cultures were then mixed with an equal volume of 1:1 ethanol:acetone mixture and frozen at −80°C. For RNA extraction, frozen samples were allowed to thaw on ice; cells were then sedimented and washed two times with TE buffer. Cells were broken mechanically using fastprep bead beater (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and the total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. On-column DNase digestion was performed and after RNA elution, residual DNA contamination was removed using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Immunoblots

S. aureus cultures were grown in RPMI/CAS overnight or to time indicated and normalized to the same OD600. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation. Supernatants were prepared as described for exoprotein profile protocol. For cytoplasmic extracts, cell pellets were treated with lysostaphin and the resulting protoplasts were sonicated for a total of one minute with ten second pulses. Proteins were resolved in a 12 or 15% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with indicated primary antibody. An AlexaFluor-680-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was used as a secondary antibody. Membranes were then scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

5’-RACE

Rapid amplification of 5’ complementary DNA ends (5’-RACE) analysis was performed using the 5’ RACE system as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, RNA was prepared from 5 hour cultures of Newman agr::tet as described above. Three nanograms were reverse transcribed using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase and gene specific primers (Primers 575, 577, 579, and 581, Table 3). The resulting cDNAs were RNase treated, purified and amplified using nested gene-specific primers (Primers 576, 578, 580, and 582, Table 3). 5’-RACE products were cloned into pCR2.1 Topo (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Subsequent plasmids were purified using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sent for sequencing using the M13 Reverse primer. Resulting sequences were aligned against the Newman genome (GenBank accession no. NC_009641) using the DNAStar program MegAlign (DNAStar, Madison, WI). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTALW (CLUSTALW).

Northern

RNA was prepared as described above. Five micrograms were separated on a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel. The RNA was transferred overnight to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT) using 20XSSC buffer (3M NaCl, 0.3M sodium citrate) and immobilized by UV cross-linking. Probes were made by PCR reaction with primers 408 and 409 (ssl1), or 410 and 411 (ssl7) from Table 3 using DIG-labeled dUTP in the dNTP mix (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT).

Prehybridization and hybridization were performed in DIG Easy Hybridization Buffer (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT). After hybridization the membranes were washed twice in 2XSSC buffer containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 15 minutes and twice in 0.1XSSC buffer containing 0.1% SDS at 50°C for 15 minutes. The DIG-labeled hybrids were detected with an anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Fab fragments) and the chemiluminiscence substrate disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro [1,2-dioxetane-3,2’-(5’-cholro) tricyclo [3.3.1.13,7] decan]-4-yl) phenyl phosphate (CSPD) (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT), and visualized by autoradiography.

GFP and YFP reporter assays

S. aureus cultures from a fresh streak on TSA+10 µg/mL chloramphenicol plates were inoculated in 5 mL RPMI/CAS+CM overnight at 37°C with shaking at 180 rpm. The overnight cultures were then diluted 1:100 into 5 mL of RPMI/CAS containing 10 µg/mL chloramphenicol in a 15 mL conical tube. When indicated, hemin was added at a final concentration of 0.5 µM. OD600 and GFP fluorescence were measured at 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 24 hours post sub-culture using a Perkin Elmer Envision 2103 Multilabel Reader.

For the reporter assay done in the presence of gramicidin, overnight cultures were grown as in above and then sub-cultured 1:100 into 2mL of RPMI/CAS containing 10 µg/mL chloramphenicol. Gramicidin was added at to a final concentration of 10, 20 or 40 µg/mL. 200µL of the diluted culture was added to a well of a 96-well plate and OD600 and GFP fluorescence were measured 26 hours post sub-culture using a Perkin Elmer Envision 2103 Multilabel Reader.

Promoter pull-downs

Biotinylated ssl promoter regions were PCR amplified as described in Table 2. 10 µg of each PCR product was conjugated to M280 streptavidin magnetic beads (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). S. aureus strain were grown for 5 hours in RPMI/CAS, pelleted and frozen at −80°C. Pellets were treated with lysostaphin, sonicated, protein concentration determined, and 2 mg of total protein was added to the PCR product conjugated to magnetic beads and the samples incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with end over end mixing. Beads were washed, and bound proteins were eluted with 1 M NaCl. Eluates were analyzed by immunoblot using a Rabbit polyclonal antibody against Rot (Jelsbak et al., 2010). Similar assay was also performed using purified His-tagged Rot. Rot was purified to homogeneity using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) from whole cell lysates of S. aureus strain Newman containing pOS1-Plgt-rotxHis. 10 µg of purified Rot protein were added to 5 µg of biotinylated ssl11 promoter conjugated to beads as described above. Rot-Pssl11 binding was competed by adding 20, 60, or 100 µg of unbiotinylated ssl11 promoter or intragenic DNA. Samples were then analyzed as described above.

Analysis of the agr locus in naturally occurring agr deficient strains

Nucleotide sequences were determined by PCR, using primers 1–10 from Table 3, and automated DNA sequencing (Traber et al., 2008, Traber & Novick, 2006). Sequences were compared with the known agr sequences of S. aureus strains COL and RN8325 (agr group I), CMRSA-1 and RN9107 (agr group Ia), and RN6607 (agr group II), using a sequence analysis suite (DNAStar, Madison, WI). agr (−) variants were derived from isogenic mixtures of agr (+) and agr (−) organisms, so the sequence of the agr (+) component was also used for comparison.

Statistical Analysis

When required, significance of differences between groups was evaluated using a Student paired t test (GraphPad Prism version 5.0; GraphPad Software).

Murine model of infection

Procedures involving animals were approved by NYU School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animal experiments were performed in accordance to NIH guidelines, the Animal Welfare Act, and US federal law. Swiss Webster mice (Hsd: ND4 females, 15–17 grams; Harlan Laboratories) were challenged retro-orbitally with approximately 1×107 CFU of S. aureus strain Newman. Four days post-infection, mice were euthanized, kidneys and hearts were removed, homogenized in sterile PBS, serially diluted and plated on TSA for colony forming unit (CFU) counts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Torres laboratory, Drs. Hope F. Ross (NYU), Andrew Darwin (NYU), Heran Darwin (NYU), and Devin Stauff (Princeton University) for critical reading of this manuscript. We are grateful to Eric P. Skaar (Vanderbilt University) for the generous gift of S. aureus strains and reagents, Dorte Frees (University Copenhagen) for providing the anti-Rot antibody, Davida Smyth (NYU) for technical assistance with the Northern blots and promoter analysis, and members of the Fraser lab for the anti-Ssl antibodies. This work was enabled by United States Public Health Service Grant K22-AI079389 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (V.J.T) and New York University School of Medicine Development Funds (V.J.T), United States Public Health AI078921 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (A.R.H), and programme grant from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (J.D.F.). M.A.B. was supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship (10PRE3420022), S.L. was supported by NIH Training Grant 5T32 AI007180-27, and M. T. was supported by NIH Training Grant AI07511. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Adhikari RP, Novick RP. Regulatory organization of the staphylococcal sae locus. Microbiology. 2008;154:949–959. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL, Roberts C, Disz T, Vonstein V, Hwang K, Overbeek R, Olson PD, Projan SJ, Dunman PM. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6739–6756. doi: 10.1128/JB.00609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldi LL, Skaar EP. Overcoming the heme paradox: heme toxicity and tolerance in bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4977–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00613-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia AS, Benson MA, Stauff DL, Torres VJ, Skaar EP. Membrane damage elicits an immunomodulatory program in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000802. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman BT, Donegan NP, Jarry TM, Palma M, Cheung AL. Evaluation of a tetracycline-inducible promoter in Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo and its application in demonstrating the role of sigB in microcolony formation. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7851–7857. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7851-7857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestebroer J, Aerts PC, Rooijakkers SH, Pandey MK, Kohl J, van Strijp JA, de Haas CJ. Functional basis for complement evasion by staphylococcal superantigen-like 7. Cell Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestebroer J, Poppelier MJ, Ulfman LH, Lenting PJ, Denis CV, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, de Haas CJ. Staphylococcal superantigen-like 5 binds PSGL-1 and inhibits P-selectin-mediated neutrophil rolling. Blood. 2007;109:2936–2943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-015461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestebroer J, van Kessel KPM, Azouagh H, Walenkamp AM, Boer IGJ, Romijn RA, van Strijp JAG, de Haas CJC. Staphylococcal SSL5 inhibits leukocyte activation by chemokines and anaphylatoxins. Blood. 2009:328–337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisset S, Geissmann T, Huntzinger E, Fechter P, Bendridi N, Possedko M, Chevalier C, Helfer AC, Benito Y, Jacquier A, Gaspin C, Vandenesch F, Romby P. Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII coordinately represses the synthesis of virulence factors and the transcription regulator Rot by an antisense mechanism. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1353–1366. doi: 10.1101/gad.423507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles BR, Thoendel M, Roth AJ, Horswill AR. Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth MC, Atkuri RV, Nanda SK, Iandolo JJ, Gilmore MS. Accessory gene regulator controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1828–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck Wardenburg J, Patel RJ, Schneewind O. Surface proteins and exotoxins are required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1040–1044. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck Wardenburg J, Williams WA, Missiakas D. Host defenses against Staphylococcus aureus infection require recognition of bacterial lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13831–13836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603072103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong YQ. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AL, Eberhardt KJ, Chung E, Yeaman MR, Sullam PM, Ramos M, Bayer AS. Diminished virulence of a sar-/agr- mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1815–1822. doi: 10.1172/JCI117530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AL, Schmidt K, Bateman B, Manna AC. SarS, a SarA homolog repressible by agr, is an activator of protein A synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2448–2455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2448-2455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MC, Wines BD, Baker H, Langley RJ, Baker EN, Fraser JD. The crystal structure of staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 11 in complex with sialyl Lewis X reveals the mechanism for cell binding and immune inhibition. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1342–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz RT, Jones MB, Gingles NA, Minogue TD, Jarrahi B, Peterson SN, Romesberg FE. Complete and SOS-mediated response of Staphylococcus aureus to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:531–539. doi: 10.1128/JB.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLUSTALW. Multiple sequence alignment. In., pp. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JE, Feil EJ. The phylogeny of Staphylococcus aureus - which genes make the best intra-species markers? Microbiology. 2006;152:1297–1305. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin BD, Seeley EH, Raab A, Feldmann J, Miller MR, Torres VJ, Anderson KL, Dattilo BM, Dunman PM, Gerads R, Caprioli RM, Nacken W, Chazin WJ, Skaar EP. Metal Chelation and Inhibition of Bacterial Growth in Tissue Abscesses. Science. 2008;319:962–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1152449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado A, Zaman S, Muthaiyan A, Nagarajan V, Elasri MO, Wilkinson BJ, Gustafson JE. The fusidic acid stimulon of Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2008;62:1207–1214. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunman PM, Murphy E, Haney S, Palacios D, Tucker-Kellogg G, Wu S, Brown EL, Zagursky RJ, Shlaes D, Projan SJ. Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7341–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7341-7353.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felden B, Vandenesch F, Bouloc P, Romby P. The Staphylococcus aureus RNome and Its Commitment to Virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002006. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TJ. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:948–958. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler VG, Jr., Sakoulas G, McIntyre LM, Meka VG, Arbeit RD, Cabell CH, Stryjewski ME, Eliopoulos GM, Reller LB, Corey GR, Jones T, Lucindo N, Yeaman MR, Bayer AS. Persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection is associated with agr dysfunction and low-level in vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1140–1149. doi: 10.1086/423145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JD, Proft T. The bacterial superantigen and superantigen-like proteins. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:226–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Stewart GC. Regulatory elements of the Staphylococcus aureus protein A (Spa) promoter. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3738–3748. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3738-3748.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger E, Adhikari RP, Jin R, Ross HF, Novick RP. Inhibition of rot translation by RNAIII, a key feature of agr function. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1038–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger E, Muir TW, Novick RP. agr receptor mutants reveal distinct modes of inhibition by staphylococcal autoinducing peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1216–1221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807760106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy AF, Hickmon SG, Skinner RA, Thomas JR, Nelson CL, Smeltzer MS. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3373–3380. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3373-3380.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo AT, Calzolari A, Cataldi AA, Bogni C, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus encodes a two-component regulatory system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo AT, Raspanti CG, Calzolari A, Nagel R. Characterization of a Tn551-mutant of Staphylococcus aureus defective in the production of several exoproteins. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:677–681. doi: 10.1139/m94-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SF, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus immune evasion and virulence. J Mol Med. 2010;88:109–114. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0573-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S, Bera A, Nerz C, Kraus D, Peschel A, Goerke C, Meehl M, Cheung A, Gotz F. Molecular basis of resistance to muramidase and cationic antimicrobial peptide activity of lysozyme in staphylococci. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-Y, Tseng CW, Stewart GC. Regulation of Rot Expression in Staphyloccus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:546–554. doi: 10.1128/JB.00536-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S, Hamada E, Kamoshida G, Yokoyama R, Takii T, Onozaki K, Tsuji T. Staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 10 (SSL10) binds to human immunoglobulin G (IgG) and inhibits complement activation via the classical pathway. Mol Imm. 2010:932–938. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelsbak L, Hemmingsen L, Donat S, Ohlsen K, Boye K, Westh H, Ingmer H, Frees D. Growth phase-dependent regulation of the global virulence regulator Rot in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian T, Cheung A, Hickey WF. Diminished virulence of an alpha-toxin mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in experimental brain abscesses. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6902–6911. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6902-6911.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. Jama. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley R, Wines B, Willoughby N, Basu I, Proft T, Fraser JD. The staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 7 binds IgA and complement C5 and inhibits IgA-Fc alpha RI binding and serum killing of bacteria. J Immunol. 2005;174:2926–2933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale KJ, Malone CL, Boles BR, Morcuende J, Horswill AR. Biofilm dispersal of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on orthopedic implant material. J Orthop Res. 2009;28:55–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale KJ, Malone CL, Boles BR, Morcuende J, Horswill AR. Biofilm dispersal of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on orthopedic implant material. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:55–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Cheung A. Repression of hla by rot is dependent on sae in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1068–1075. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01069-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Zheng L, Landwehr C, Lunsford D, Holmes D, Ji Y. Global regulation of gene expression by ArlRS, a two-component signal transduction regulatory system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5486–5492. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5486-5492.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna AC, Ray B. Regulation and characterization of rot transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 2007;153:1538–1545. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara PJ, Bayer AS. A rot mutation restores parental virulence to an agr-null Staphylococcus aureus strain in a rabbit model of endocarditis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3806–3809. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3806-3809.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara PJ, Milligan-Monroe KC, Khalili S, Proctor RA. Identification, Cloning, and Initial Characterization of rot, a Locus Encoding a Regulator of Virulence Factor Expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3197–3203. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3197-3203.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan V, Elasri MO. SAMMD: Staphylococcus aureus microarray meta-database. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:351. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizet V. Understanding how leading bacterial pathogens subvert innate immunity to reveal novel therapeutic targets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP. The staphylococcus as a molecular genetic system. In: Novick RP, editor. Molecular Biology of the Staphylococci. New York: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1429–1449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Geisinger E. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Projan S, Kornblum J, Ross H, Kreiswirth B, Moghazeh S. The agr P-2 operon: an autocatalytic sensory transduction system in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Gen Genet. 1995:446–458. doi: 10.1007/BF02191645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard TK, Pallister KB, Ruzevich P, Griffith S, Vuong C, Voyich JM. SaeR binds a consensus sequence within virulence gene promoters to advance USA300 pathogenesis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:241–254. doi: 10.1086/649570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson PD, Kuechenmeister LJ, Anderson KL, Daily S, Beenken KE, Roux CM, Reniere ML, Lewis TL, Weiss WJ, Pulse M, Nguyen P, Simecka JW, Morrison JM, Sayood K, Asojo OA, Smeltzer MS, Skaar EP, Dunman PM. Small molecule inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus RnpA alter cellular mRNA turnover, exhibit antimicrobial activity, and attenuate pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscarsson J, Harlos C, Arvidson S. Regulatory role of proteins binding to the spa (protein A) and sarS (staphylococcal accessory regulator) promoter regions in Staphylococcus aureus NTCC 8325-4. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscarsson J, Tegmark-Wisell K, Arvidson S. Coordinated and differential control of aureolysin (aur) and serine protease (sspA) transcription in Staphylococcus aureus by sarA, rot and agr (RNAIII) Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:365–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Reniere ML, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Skaar EP, DeLeo FR. Neutrophil microbicides induce a pathogen survival response in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2008;180:500–509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantrangi M, Singh VK, Wolz C, Shukla SK. Staphylococcal superantigen-like genes, ssl5 and ssl8, are positively regulated by Sae and negatively by Agr in the Newman strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MM, Mack JL, Hall PR, Alsup AA, Alexander SM, Sully EK, Sawires YS, Cheung AL, Otto M, Gresham HD. Apolipoprotein B Is an innate barrier against invasive Staphylococcus aureus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishchany G, McCoy AL, Torres VJ, Krause JC, Crowe JE, Jr., Fabry ME, Skaar EP. Specificity for human hemoglobin enhances Staphylococcus aureus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queck SY, Jameson-Lee M, Villaruz AE, Bach TH, Khan BA, Sturdevant DE, Ricklefs SM, Li M, Otto M. RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Cell. 2008;32:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfork JM, Timmins GS, Harris MN, Chen X, Lusis AJ, Otto M, Cheung AL, Gresham HD. Inactivation of a bacterial virulence pheromone by phagocyte-derived oxidants: new role for the NADPH oxidase in host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13867–13872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402996101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said-Salim B, Dunman PM, McAleese FM, Macapagal D, Murphy E, McNamara PJ, Arvidson S, Foster TJ, Projan SJ, Kreiswirth BN. Global Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus Genes by Rot. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:610–619. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.2.610-619.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind O, Model P, Fischetti VA. Sorting of protein A to the staphylococcal cell wall. Cell. 1992;70:267–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90101-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shopsin B, Drlica-Wagner A, Mathema B, Adhikari RP, Kreiswirth BN, Novick RP. Prevalence of agr dysfunction among colonizing Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1171–1174. doi: 10.1086/592051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]