Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Examine the longitudinal effects of personal narratives about mammography and breast cancer compared with a traditional informational approach.

METHOD

African American women (n=489) ages 40 and older were recruited from low-income neighborhoods in St. Louis, MO and randomized to watch a narrative video comprised of stories from African American breast cancer survivors or a content-equivalent informational video. Effects were measured immediately post-exposure (T2) and at 3- (T3) and 6-month (T4) follow-up. T2 measures of initial reaction included positive and negative affect, trust, identification, and engagement. T3 message-processing variables included arguing against the messages (counterarguing) and talking to family members about the information (cognitive rehearsal). T4 behavioral correlates included perceived breast cancer risk, cancer fear, cancer fatalism, perceived barriers to mammography, and recall of core messages. Structural equation modeling examined inter-relations among constructs.

RESULTS

Women who watched the narrative video (n=244) compared to the informational video (n=245) experienced more positive and negative affect, identified more with the message source, and were more engaged with the video. Narratives, negative affect, identification, and engagement influenced counterarguing, which in turn influenced perceived barriers and cancer fatalism. More engaged women talked with family members more, which increased message recall. Narratives also increased risk perceptions and fear via increased negative affect.

CONCLUSIONS

Narratives produced stronger cognitive and affective responses immediately, which in turn influenced message processing and behavioral correlates. Narratives reduced counterarguing and increased cognitive rehearsal, which may increase acceptance and motivation to act on health information in populations most adversely affected by cancer disparities.

Keywords: mammography, breast cancer survivors, health communication, storytelling, narratives, cancer disparities

While stories are as old as human communication, using stories to improve the public’s health prompts new and exciting research questions and applications. Stories are experiencing a resurgence everywhere. StoryCorps, the world’s largest oral history project, now routinely brings stories to a nation of listeners through National Public Radio and online (Isay, 2008). Bestselling books extol the power of stories to “make ideas stick” (Heath & Heath, 2007). Narratives are increasingly available as sources of health information for patients and the public (Eddens et al., 2009; Khangura, Bennett, Stacey, & O’Connor, 2008), and clinical, behavioral, and social science researchers are touting the unique capabilities of stories to enhance understanding, model desirable behaviors, deliver support, and deal with complex decisions and emotions (Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; Hydén, 1997; Kreuter et al., 2007).

The process of developing stories and their function may be similar across the globe, but this process is influenced by culturally-specific rules and contexts (Banks-Wallace, 2002). African Americans have a rich history of oral storytelling and so narrative health communications may be especially effective. One of the most notable applications of cultural narratives for health communication is the Witness Project, which promotes breast and cervical cancer screening through cancer survivors who talk about their experiences with other African American women (Erwin, Spatz, Stotts, & Hollenberg, 1999; Erwin, Spatz, Stotts, Hollenberg, & Deloney, 1996; Erwin, Spatz, & Turturro, 1992).

Numerous studies, reviews, and meta-analyses have examined the effect of narrative vs. non-narrative (usually statistical) information on persuasion. Findings have been equivocal; several studies have found that narratives are more persuasive (Harte, 1976; Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Sherer & Rogers, 1984; Taylor & Thompson, 1982), whereas others have found that statistical evidence (i.e., averages, percentages) is superior to narrative (Allen & Preiss, 1997; Baesler & Burgoon, 1994), especially when controlling for the vividness of the evidence (Baesler & Burgoon, 1994). Comparing across studies is difficult because different definitions of narrative and measures of persuasion are used. Hinyard and Kreuter (2007) suggest that a combination of narrative and statistical evidence may be most effective, but we still need to understand how each format influences attitudes and behavior to effectively combine information to maximize communication impact (p. 784).

Understanding the processes and mechanisms through which stories influence health-related decisions and actions is critical to maximizing their effectiveness and developing appropriate applications for use in practice settings. In contrast to informational and expository communication that presents reasons and arguments in favor of a particular course of action, narratives use storytelling and testimonials to depict events and consequences for characters (Kreuter et al., 2007). Narratives are expected to influence behavior indirectly through attitudes, norms, self-efficacy, and intention (Freimuth & Quinn, 2004; Petraglia, 2007). The Elaboration Likelihood Model suggests that issue involvement or personal relevance determines a person’s motivation to process information and also may moderate the effectiveness of persuasive appeals on behavior change (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). However, narratives are expected to be engaging and elicit less resistance because they are generally perceived to be less overtly persuasive (Moyer-Guse, 2008; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Thus, Slater and Rouner (2002) argue that instead of issue involvement, we should be concerned with message involvement via engagement and identification with the characters when evaluating effects of narratives.

Effects of Narrative

Previous studies have identified a wide range of narrative effects that could enhance health and social behaviors [see Green, Strange, & Brock, 2002 for an overview]. This study explored the effects of narratives on seven of the most prominent of such variables (engagement, identification, trust, affect, counterarguing, talking to others, and recall), and in turn the effects of these variables on pre-behavioral outcomes or correlates of mammography (cancer fear, cancer fatalism, perceived risk of breast cancer, and perceived barriers to mammography). The causal direction and relative importance of these relationships are not yet well understood (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004; Moyer-Guse, 2008). By examining these relationships in a longitudinal study, this study provides a clearer picture of the pathway through which narratives may influence behavior.

Engagement, absorption, and transportation are three terms often used interchangeably to reflect an individual’s cognitive and affective immersion in a story (Slater & Rouner, 2002). Engagement (the term used in this paper) with a narrative is expected to reduce counterarguing and increase cognitive rehearsal and recall (Green, 2008; Slater, 2002; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Some researchers have suggested that greater engagement leads to greater identification with the characters, but it doesn’t always have this effect (Green, 2008; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Whereas issue involvement is determined by an individual’s pre-existing beliefs or group memberships, engagement can occur despite an individual’s beliefs and instead depends on elements of plot structure and identification with the characters (Slater, 2002).

Identification has been operationalized in different ways, but in general represents perceived similarity to and liking of the characters. A more extreme definition requires viewers to take the perspective of the character; “see through their eyes” (Moyer-Guse & Nabi, 2010; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Identifying with characters (message source) is expected to increase empathy and cognitive rehearsal, decrease counterarguing, and influence attitudes, perceived risk, perceived norms, and behaviors (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004; Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; Moyer-Guse, 2008; Slater, 2002; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Identification may be enhanced by the perceived credibility of the message source or characters or vice versa. Credibility or trustworthiness may be established by a character’s experience (e.g., cancer survivor) or professional credentials (e.g., physician) (Kreuter et al., 2007).

Emotions affect what people notice and remember (Dolan, 2002), in part because they evoke physiological reactions that add a dimension of experience (Kensinger, 2008). Narratives that evoke strong emotions might therefore lead to greater recall. Additionally, narratives may evoke more empathy, and the extent to which the participant is emotionally involved with the characters may be more important than identification (Slater, 2002). Although some studies have viewed emotions as a direct effect of a stimulus (Bae, 2008; Dunlop, Wakefield, & Kashima, 2008), other researchers posit that engagement with the stimulus produces an emotional response (Chang, 2008; Green, 2008).

Counterarguing involves generating thoughts that counter, discount or reject a persuasive message or its implications, thereby reducing persuasion (i.e., attitude or behavior change). Both identification and engagement are expected to block one’s ability to produce strong counterarguments while hearing or reading a message, due to less critical evaluation (Moyer-Guse, 2008; Slater, 2002). However, the relative impact of these variables on counterarguing is unknown (Moyer-Guse, 2008). Counterarguing and other defensive responses appear to be the critical mediators of the hypothesized effect of narratives on message acceptance and persuasion, which affects changes in attitudes and behavior (Moyer-Guse, 2008; Moyer-Guse & Nabi, 2010; Slater & Rouner, 2002).

Study Hypotheses

The power of narrative communication may lie in its ability to reduce the amount and effectiveness of counterarguing and through viewer’s identification with characters, which in turn, promote specific beliefs and behaviors (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004). Our previous study tested measurement models of our latent constructs and found that narratives had stronger immediate effects on cognitive and affective responses compared with an informational video (McQueen & Kreuter, 2010). This study expands upon our previous work to examine the direct and indirect effects of narrative vs. informational videos about breast cancer and mammography use on cognitions, affect, message processing, and behavioral correlates in a longitudinal structural equation model. Specific hypotheses derived from the literature that were tested with our data for this report were based on conceptual models and reviews (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004; Dunlop, Wakefield, & Kashima, 2008; Green, 2006, 2008; McGuire, Lindzey, & Aronson, 1985; Moyer-Guse, 2008; Slater, 2002; Slater & Rouner, 2002), empirical studies (Eagly, Kulesa, Brannon, Shaw, & Hutson-Comeaux, 2000; Green & Brock, 2000; Kensinger, 2008; Mandler & Johnson, 1977; Moyer-Guse & Nabi, 2010), and our previous work (Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; Kreuter et al., 2007; McQueen & Kreuter, 2010).

Counterarguing will be negatively associated with watching the narrative vs. informational video, greater identification with the characters, and greater engagement in the video.

Cognitive rehearsal (i.e., talking to others) will be positively associated with affective responses to the video, identification with the characters, and engagement in the video. Counterarguing also may be positively associated with cognitive rehearsal.

The recall of key messages will be positively associated with watching the narrative vs. informational video, greater emotional responses to the video, greater engagement, and greater cognitive rehearsal (i.e., talking to family). Counterarguing also may be positively associated with recall of key messages.

Perceived risk and pro-message attitudes (i.e., low perceived mammography barriers) will be positively associated with watching the narrative vs. informational video and identifying with the characters.

Methods

Data were collected as part of a randomized trial to compare women’s mammography use after watching either a narrative or informational video (Kreuter et al., 2010). The narrative video was comprised of personal stories from African American breast cancer survivors. A content-equivalent informational video provided information about breast cancer and mammography in a didactic, expository form narrated by an African American woman. This report focuses on the longitudinal effects of watching the video with particular focus on the inter-relations between constructs that are important in theories of health communication and narrative effects. Details about the trial including recruitment, participation, and intervention development, pre-testing, and content are reported elsewhere (Kreuter et al., 2010) and follow from previous studies (Kreuter et al., 2008). Study materials and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Saint Louis University and Washington University in St. Louis.

Participants and Procedures

Between October 2007 and March 2008, participants (N=489) were recruited using neighborhood canvassing approaches in areas of St. Louis, MO where the rate of late stage breast cancer diagnosis was twice the expected rate for the state (Lian, Jeffe, & Schootman, 2008). For sampling, neighborhoods in these areas were divided into block units, and 10 block units per week were randomly selected without replacement. Recruitment flyers were hand delivered to all occupied residences in each selected block unit and placed in nearby public venues such as large apartment complexes and grocery stores. Flyers were designed to appeal (i.e., targeted) to the study population and included pictures of the Neighborhood Voice mobile research unit, a van customized for data collection in the field (Alcaraz, Weaver, Andresen, Christopher, & Kreuter, In press) where all research activities took place. Each flyer included information about the trial, eligibility criteria, dates and times the Neighborhood Voice would be visiting their street, and how women could participate (by visiting the Neighborhood Voice when it was in their neighborhood).

Eligibility criteria included being female, African American, age 40 years and older, never diagnosed with breast cancer, and able to complete a brief literacy screener written at the fifth-grade level. Onboard the Neighborhood Voice, participants provided informed consent and were randomly assigned to watch either the narrative or informational video and complete surveys on a 20″ touch-screen computer monitor in one of two private interview areas. Surveys were completed in the van immediately before (baseline; T1) and immediately after (T2) women watched either the narrative or informational video. Telephone surveys were completed at 3 (T3) and 6 (T4) months post-intervention.

Measures

Immediate outcomes were measured immediately after viewing the video (T2) and measurement models for all latent variables were tested previously (McQueen & Kreuter, 2010). Measures were based on those used in previous studies and were adapted for this study, generally with the objective of reducing participant burden. Internal consistency for each scale is estimated with Cronbach’s alpha from this study sample. Positive (4 items; alpha = .69) and Negative Affect (7 items; alpha = .79) in response to watching the video was assessed using items containing adjectives from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) e.g., Watching this video made me feel concerned (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Responses ranged from 1=not at all to 5=extremely. Identification with the message source was assessed by six items measuring perceived similarity of the character(s) in the video to the participant (e.g., “The women in this video are a lot like me”) (Cohen, 2001; Simons, Berkowitz, & Moyer, 1970) and two items measuring liking of the message source (e.g., “The women in this video could be good friends of mine”) (alpha = .83) (Roskos-Ewoldsen & Fazio, 1992). Trust in the information and source was assessed with a seven-item scale (e.g., “The women in this video are sincere”) (alpha = .79) (Wheeless & Grotz, 1977). Identification and trust response options ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a 5-point scale. Engagement with the video was assessed using 3 of 15 items from Green and Brock’s (Green & Brock, 2000) Transportation scale using a 7-point response scale (not at all – very much) (alpha = .56). The word “reading” was changed to “watching” in the wording of some items e.g., “I wanted to keep watching this video to find out more.”

Message processing variables were included in the telephone survey at 3-month follow-up (T3). Counterarguing was assessed with two items (r = .30, p < .001): “Since watching the video I had a lot of thoughts against the things said in the video” and “The information in the video is different from what I believe”. Response options ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a 5-point scale. A single item assessed cognitive rehearsal, “After watching the video did you talk to any family members about the new information?” (yes/no).

Behavioral correlates were measured on the 6-month follow-up survey (T4) and were selected because they have been correlated with mammography use in the literature. Cancer fear (alpha = .78) was assessed with three items from a previously validated 8-item scale e.g., “Thinking about breast cancer scares me a lot” (V.L. Champion et al., 2004). Cancer fatalism (alpha = .68) was assessed with three items from a previously validated 15-item scale e.g., “Cancer will kill you no matter when it is found and how it is treated” (Powe, 1996). Absolute perceived risk of developing breast cancer was assessed with a single item indicating women’s agreement with a high likelihood of developing breast cancer similar to other measures in the literature (S.W. Vernon, Myers, & Tilley, 1997; S. W. Vernon, Myers, Tilley, & Li, 2001). Mammography barriers was assessed by 5 items (alpha = .53) from a previously validated 19-item scale e.g., “Having a mammogram would take too much time” (V. L. Champion & Springston, 1999). Response options for fear, fatalism, perceived risk and barriers ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a 5-point scale. Message Recall was assessed by asking women what they remembered most about the video. Open-ended responses were recorded, transcribed and coded by trained research staff blinded to study condition. Coders rated each response for topic (mentioned “cancer,” “breast,” “breast cancer,” “mammogram” or “mammography”), content (mentioned one of the 11 key messages in the video or risk of getting breast cancer or cancer, talking about breast cancer or cancer, getting a mammogram, breast exam or breast check) and messenger (mentioned the women talking in the video). Intercoder reliability for these variables was high (Kappa=0.98, 0.84 and 0.92, respectively). A composite measure was created to categorize women as recalling any of the video’s key messages (n=279) vs. none (n=154).

Data Analysis

We used a structural equation model (SEM) to examine the hypothesized direct and indirect effects of narrative vs. informational cancer communication. SEM is well suited to our aims because in a single analysis we can examine the inter-relations between multiple variables over time. Additionally, we can include a combination of latent and manifest variables and account for measurement error which allows for greater precision in our estimates.

We tested a saturated structural equation model (SEM) that conformed to our three periods of data collection which included all possible structural paths. Measures at each timepoint were allowed to correlate. Non significant paths and covariances were deleted from the final model. Modification indices were consulted for potential improvements in model fit. SEM analyses were conducted with Mplus 5.2. Two endogenous variables (talked to family, message recall) were dichotomous and therefore we used the WLSMV estimation method with full information maximum likelihood. Tests of indirect effects were computed in Mplus using the Delta method to identify significant mediators in the model.

We used multiple fit indices to evaluate overall model fit including the comparative fit index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI values between 0.90–0.95 or above suggest adequate to good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995, 1999) and RMSEA values <.06 suggest good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995).

Results

Sample characteristics

Most women had a high school education or less (67%), an annual household income of $20,000 or less (77%), and a prior mammogram (89%). Among women age 40–49, 59% had a mammogram in the 24 months prior to the intervention. Among women age 50 and older, 56% had a mammogram in the 12 months prior to the intervention and 78% had a mammogram in the 24 months prior to the intervention. The average age was 61 years old (SD=12). Intervention groups were equivalent at baseline (T1) on demographics, cancer-related beliefs, and behaviors (Kreuter et al., 2010).

Structural model: Direct effects

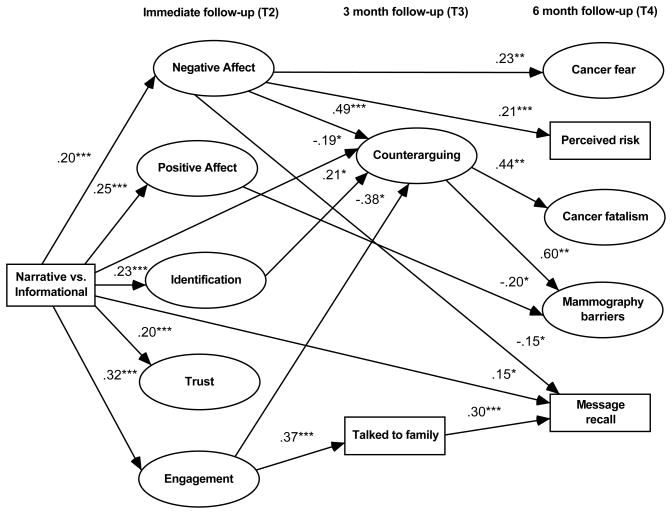

The saturated structural model provided adequate fit to the data; χ2(146) = 312.07, p < .001; CFI = .85; RMSEA = .048. In a series of analyses, non significant paths and covariances were removed from the final model; χ2(145) = 290.62, p < .001; CFI = .87; RMSEA = .045. Standardized path estimates in the final model are presented in Figure 1 and significant correlations between model variables are presented in Table 1. All factor loadings were significant and strong (>.40 with only 2 exceptions >.30) and are not reported here. Due to the number of variables involved, a correlation matrix is not reported here, but can be obtained from the first author.

Figure 1. Longitudinal structural model showing significant paths only.

Standardized path coefficients shown.

* p< .05; ** p< .01; *** p< .001

Correlations between model variables are not shown, but are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Significant Correlations Between Model Variables (Not Shown in Figure 1)

| Variables | Standardized parameter estimate | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative affect | Positive affect | .14* |

| Identification | .12* | |

| Engagement | .24* | |

| Positive affect | Identification | .45*** |

| Trust | .52*** | |

| Engagement | .56*** | |

| Identification | Trust | .71*** |

| Engagement | .43*** | |

| Trust | Engagement | .49*** |

| Counterarguing | Talked to family | −.31* |

| Cancer fear | Perceived risk | .32*** |

| Cancer fatalism | .40*** | |

| Mammography barriers | .46** | |

| Perceived risk | Cancer fatalism | .17* |

| Mammography barriers | .18* | |

| Cancer fatalism | Mammography barriers | .74*** |

p< .05;

p< .01;

p< .001

Affect, identification, trust and engagement were all measured immediately after watching the video (T2) and were positively correlated (Table 1). Greater counterarguing reported at 3-month follow-up (T3) was associated with less talking to others about the information in the video. Message recall was not associated with any of the behavioral correlates variables measured at 6-month follow-up (T4). Finally, we found positive associations between the behavioral correlates (cancer fear and fatalism, perceived risk, and mammography barriers) (Table 1).

As shown previously (McQueen & Kreuter, 2010), women had stronger cognitive and affective responses immediately after watching the narrative video compared with the informational video (Figure 1). Expanding on our previous analyses, we found that watching the narrative video and being more engaged with the video were negatively associated with subsequent counterarguing (supports hypothesis 1), whereas identification with the characters and negative affect were positively associated with counterarguing (opposite of hypothesis 1; Figure 1). Greater cognitive rehearsal (i.e., talking to family members about the information) was positively associated with engagement, but was not associated with positive or negative affect or identification variables (partial support for hypothesis 2). Message recall was positively associated with watching the narrative vs. informational video and talking to others (support for hypothesis 3), but was negatively associated with negative affect immediately after watching the video (opposite of hypothesis 3). Behavioral correlates measured at 6-month follow-up (T4) were not directly affected by the type of video or identification (no support for hypothesis 4); however, perceived risk and cancer fear were positively associated with negative affect. Additionally, reporting more positive affect immediately after watching the video (T2) was associated with perceiving fewer mammography barriers at 6-month follow-up (T4). Greater counterarguing reported at 3-month follow-up (T3) was associated with more fatalistic beliefs about cancer and perceiving more mammography barriers at 6-month follow-up (T4).

Indirect effects

We identified significant, indirect effects of the narrative video on all follow-up measures (Table 2). For example, the narrative (vs. informational) video reduced counterarguing directly as well as influenced counterarguing indirectly through its effects on negative affect and engagement (Figure 1). Watching the narrative video also increased message recall directly and indirectly through greater engagement with the video, which in turn was related to more cognitive rehearsal (i.e., talking to family) which increased recall (some indirect support for hypothesis 3). The indirect tests also provide some support for hypothesis 4: watching the narrative vs. informational video indirectly increased cancer fear and perceived risk through negative affect (Table 2). Negative affect and counterarguing also mediated the positive effect of watching the narrative video on cancer fatalism and perceived mammography barriers.

Table 2.

Significant Indirect Effects of the Narrative Video

| Indirect Effects of Narrative video on: | Beta | Z-score |

|---|---|---|

| Counterarguing | ||

| via Negative affect | 0.10 | 2.84** |

| via Identification | 0.05 | 1.88† |

| via Engagement | −0.12 | −2.24* |

|

| ||

| Talked to family | ||

| via Engagement | 0.12 | 3.51*** |

|

| ||

| Cancer fear | ||

| via Negative affect | 0.05 | 2.38* |

|

| ||

| Perceived risk | ||

| via Negative affect | 0.04 | 2.67** |

|

| ||

| Cancer fatalism | ||

| via Negative affect –> Counterarguing | 0.04 | 2.58** |

| via Identification –> Counterarguing | 0.02 | 1.87† |

| via Engagement –> Counterarguing | −0.05 | −2.26* |

| via Counterarguing | −0.08 | −2.03* |

|

| ||

| Mammography barriers | ||

| via Negative affect –> Counterarguing | 0.06 | 2.54* |

| via Identification –> Counterarguing | 0.03 | 1.83† |

| via Engagement –> Counterarguing | −0.07 | −2.25* |

| via Positive affect | −0.05 | −2.24* |

| via Counterarguing | −0.11 | −1.93† |

|

| ||

| Message recall | ||

| via Engagement –> Talked to family | 0.03 | 2.42* |

| via Negative affect | −0.03 | −1.84† |

p<.10;

p< .05;

p< .01;

p< .001

Additional post-hoc tests were conducted to examine the indirect effects of identification when type of video was not included in the analysis in an attempt to show some support for hypothesis 4. Counterarguing was a significant mediator of the effect of identification on cancer fatalism (β=.13, Z=1.97, p<.05) and mammography barriers (β=.10, Z=2.08, p<.05), which provides some support for the significant effect of identification in hypothesis 4.

Discussion

This study addressed a need for more theory-based experimental research on the effects of narrative communication (Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007; Petraglia, 2007; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Our results support claims in the literature that narratives increase persuasion by reducing counterarguing (Green & Brock, 2000; Slater & Rouner, 2002). The SEM results also clearly illustrate the multiple direct and indirect effects of narratives on affect, cognitions, engagement, counterarguing, cognitive rehearsal, recall, and behavioral correlates. Our inclusion of multiple important factors associated with watching the narrative video and our simultaneous estimation of all the inter-relations between factors extends the current empirical findings in the literature and supports hypotheses for future testing and replication. Our results suggest that narratives have several unique advantages over traditional informational approaches and are likely to enhance health communications for cancer prevention and control. Specifically, narratives appear to be a promising intervention strategy for addressing health disparities (Houston et al., 2011), but future research should determine whether the use of narratives is desirable in all cases (Fagerlin, Wang, & Ubel, 2005; Khangura, Bennett, Stacey, & O’Connor, 2008; Ubel, Jepson, & Baron, 2001). Theory and conceptual models from communication and psychology informed our hypotheses, and additional research is needed to further test and refine assumptions about the effects of narratives on beliefs, intentions, and behaviors. Future health psychology research should determine whether the mechanisms observed in the current study and others vary by population, health behavior, or other contextual factors.

Counterarguing played a central and important role in our model of the longitudinal effects of narrative vs. informational videos. Effective counterarguing is typically associated with less attitude change. Not all individuals process risk information in a rational, unbiased way, and knowing the counterarguments people generate may allow researchers to address and circumvent these thoughts in health communication materials. Similarly, health communications that elicit a large amount of counterarguments and increase the likelihood of message rejection should be abandoned.

Consistent with the literature (Green, 2006; Hinyard & Kreuter, 2007), less counterarguing was reported among narrative viewers and among those more engaged in the video. However, the positive associations of negative affect and identification with counterarguing were unexpected. It may be that negative emotions about breast cancer elicited defensive responses. Our measure of counterarguing was limited to two survey items. Highly engaging narratives may not permit the intrusive, concurrent “think aloud” procedures used to measure information processing and defenses such as message rejection, but a post-exposure “thought-listing” measure of counterarguing may have elucidated the specific thoughts women had in favor of and in contrast to the messages in the video (Cacioppo, von Hippel, & Ernst, 1997). Additional research is needed to identify the specific counterarguments women generated after watching the videos and whether specific counterarguments produce similar patterns of association with other variables (e.g., identification, engagement, talking with others, and behavioral correlates). For example, some women may have counterargued against messages about the efficacy of mammograms for finding cancer early, while others may have counterargued about the reasons why many African American families historically did not talk openly about cancer. These two counterarguments might affect different variables in different ways. Future research is needed to assess additional measures of defensive processes to better understand whether and how narratives may have both positive and negative effects on message processing (also see Ubel, Jepson, & Baron, 2001; Winterbottom, Bekker, Conner, & Mooney, 2008). A recent study examined counterarguing, reactance, and perceived invulnerability as different types of resistance to persuasion, and found different patterns of association with engagement, identification, and similarity (Moyer-Guse & Nabi, 2010). Aspects of the messages in the video that may have influenced counteraruging and warrant further investigation include: 1) a disparity focus related to the presentation of breast cancer rates among African Americans and Whites (Nicholson et al., 2008), 2) a lack of communication about breast cancer within African American families, and 3) the use of two-sided arguments, which present two points of view and arguments to counter the opposing view (Allen, 1991).

Researchers often ask recipients of health information whether they shared the materials or talked about the information with others. Such sharing suggests the information was perceived as interesting or useful, and talking about it with others provides cognitive rehearsal and social reinforcement (Slater & Rouner, 2002). In our study, talking about the video to others increased later recall of key messages. Based on our results, designing health communications that elicit a high level of engagement would be expected to prompt recipients to talk with others about the information. Alternatively, strategies for facilitating cognitive rehearsal can be embedded into the intervention itself (Maibach & Flora, 1993). Conceptual papers have suggested that affect and identification also will increase cognitive rehearsal (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004; Dunlop, Wakefield, & Kashima, 2008), but our results did not support these associations. Similarly, others have suggested that counterarguing may increase recall (Eagly, Kulesa, Brannon, Shaw, & Hutson-Comeaux, 2000), but we did not find this association. We did find a significant inverse association between counterarguing and cognitive rehearsal. Some differences between findings from our and other studies may be due to our use of a structural equation model rather than independent analyses of each outcome variable, because it takes into account the simultaneous effects of multiple interrelated constructs. Although the inter-correlations have not been previously reported for this group of variables before, several studies have reported specific correlations (e.g., perceived risk and cancer worry/fear) that are consistent with our results (Farmer, Reddick, D’Agostino, & Jackson, 2007; Katapodi, Lee, Facione, & Dodd, 2004; McQueen et al., 2010; Tiro et al., 2005; S. W. Vernon, Myers, Tilley, & Li, 2001).

Strengths and Limitations

As with all structural equation models, model fit could have been better and alternative models may fit equally well if not better. Modification indices did not suggest substantive changes to the measurement or structural models that made theoretical or methodologic sense. The variables included in the model were selected based on the available data and the desire for parsimony and were not meant to be an exhaustive list of the important effects of narratives. Additionally, this study used brief measures to reduce participant burden while assessing numerous constructs, which negates established validity; however, our prior work demonstrated the independence and utility of latent measures, strengthening our confidence in their construct validity (McQueen & Kreuter, 2010).

In this study, the effect of message format (i.e., narrative vs. information videos) was confounded with message source (multiple breast cancer survivors vs. one African American female narrator). The purpose of this study was not to isolate the storyteller from the story, but to examine the effect of experiential stories concerning a public health problem. Future studies interested in teasing apart the effects of message format vs. message source could compare cancer survivor(s) who share factual information only vs. stories.

Our participants had a higher mammography adherence rate in the two years pre-intervention (74%) compared with a national sample of African American women age 40 and older in 2008 (68%) (American Cancer Society, 2010). Further, not everyone in this sample was due for a mammogram at baseline (T1). Thus, our sample may endorse more positive beliefs about breast cancer screening and be more receptive to health communications promoting mammography compared to women with less mammography experience. However, our sample had low educational attainment and low income. Lower education has been associated with higher perceived susceptibility to breast cancer, fear and fatalism about breast cancer, and lower self-efficacy for getting mammograms (Zollinger et al., 2010). Despite potential mean level differences in constructs measured, we have confidence that the observed longitudinal effects (i.e., mechanisms) of narrative communication would be comparable across other samples of African American women, but further studies are needed to confirm these effects.

Strengths of this study include the use of longitudinal data and testing a single structural model with multiple variables identified as important effects of narratives and all the inter-relations among variables. Additionally, our study sample was comprised of low income, African American women who completed the first part of the study in their neighborhoods, which extends the bulk of the experimental research conducted with well educated white samples (Greene & Brinn, 2003; Lemal & Van den Bulck, 2010; Limon & Kazoleas, 2004). If health communication, specifically the use of narratives, is going to be useful in improving population health, we should be testing its effect on major public health problems among populations at higher risk. Recent interventions using narratives have focused on minority groups (Ashton et al., 2010; Houston et al., 2011; Larkey & Gonzalez, 2007; Larkey, Lopez, Minnal, & Gonzalez, 2009), but more diverse samples should be involved in future studies to test assumptions about the cultural or demographic differences in the effects of narratives.

Future research

Although health communication interventions are sometimes able to reach broad audiences, they are generally expected to have only small effects on behavior (Freimuth & Quinn, 2004). The limitations of health communications may be especially relevant for at-risk populations experiencing health disparities and when behaviors are dependent, at least in part, on environmental factors outside the immediate control of the individual (e.g., access to medical care, cost). Few studies have examined behavioral outcomes of narratives, but results seem promising (Houston et al., 2011; Lemal & Van den Bulck, 2010; Moyer-Guse & Nabi, 2010; Ricketts, Shanteau, McSpadden, & Fernandez-Medina, 2010) and more future research is needed to identify the (likely indirect) effects of narratives on intentions and behavior. We examined correlates of mammography use as outcomes in our study that are hypothesized to prompt behavior. Additional correlates or potential mediators that deserve attention in future studies include social norms, self-efficacy, and intention. Additionally, most of the published research has focused on the comparison between narrative vs. statistical or factual information formats (Allen & Preiss, 1997; Baesler & Burgoon, 1994; Taylor & Thompson, 1982); however, more research is needed to compare the effects of different narrative formats (e.g., first-person experiential stories, testimonials, fictional stories, anecdotes, and exemplars) and different modes of communication (e.g., print, audio, video).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute’s Centers of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research (CECCR) program (CA-P50-95815; PI: Kreuter). The first author also was supported by a Junior Investigator Award as part of the CECCR and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (CPPB-113766).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea

References

- Alcaraz KI, Weaver NL, Andresen EM, Christopher K, Kreuter MW. The Neighborhood Voice: Evaluating a mobile research vehicle for recruiting African Americans to participate in cancer control studies. Evaluation and the Health Professions. doi: 10.1177/0163278710395933. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. Meta-analysis comparing the persuasiveness of one-sided and two-sided messages. Western Journal of Speech Communication. 1991;55(4):390–404. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Communication Research Reports. 1997;14:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton CM, Houston TK, Williams JH, Larkin D, Trobaugh J, Crenshaw K, et al. A stories-based interactive DVD intended to help people with hypertension achieve blood pressure control through improved communication with their doctors. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H. Entertainment-education and recruitment of cornea donors: The role of emotion and issue involvement. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:20–36. doi: 10.1080/10810730701806953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baesler EJ, Burgoon JK. The temporal effects of story and statistical evidence on belief change. Communication Research. 1994;21(5):582–602. [Google Scholar]

- Banks-Wallace J. Talk that talk: Storytelling and analysis rooted in African American oral tradition. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(3):410–426. doi: 10.1177/104973202129119892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, von Hippel W, Ernst JM. Mapping cognitive structures and processes through verbal concent: The thought-listing technique. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(6):928–940. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.6.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion VL, Skinner CS, Menon U, Rawl S, Giesler R, Monahan P, et al. A breast cancer fear scale: psychometric development. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(6):753–762. doi: 10.1177/1359105304045383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion VL, Springston J. Mammography adherence and beliefs in a sample of low-income African American women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;6(3):228–240. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0603_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. Increasing mental health literacy via narrative advertising. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:37–55. doi: 10.1080/10810730701807027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication and Society. 2001;4(3):245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Narrative persuasion and overcoming resistance. In: Knowles ES, Linn JA, editors. Resistance and Persuasion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ. Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science. 2002;298(5596):1191–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1076358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop S, Wakefield M, Kashima Y. Can you feel it? Negative emotion, risk, and narrative in health communication. Media Psychology. 2008;11:52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Kulesa P, Brannon LA, Shaw K, Hutson-Comeaux S. Why counterattitudinal messages are as memorable as proattitudinal messages: The importance of active defense against attack. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26(11):1392–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Eddens KS, Kreuter MW, Morgan JC, Beatty KE, Jasim SA, Garibay L, et al. Disparities by race and ethnicity in cancer survivor stories available on the web. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(4):e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts C, Hollenberg JA. Increasing mammography practice by African American women. Cancer Practice. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts C, Hollenberg JA, Deloney LA. Increasing mammography and breast self-examination in African American women using the Witness Project model. Journal of Cancer Education. 1996;11(4):210–215. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Turturro CL. Development of an African-American role model intervention to increase breast self-examination and mammography. Journal of Cancer Education. 1992;7(4):311–319. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: Is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Medical Decision Making. 2005;25:398–405. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05278931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer D, Reddick B, D’Agostino R, Jr, Jackson SA. Psychosocial correlates of mammography screening in older African American women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34(1):117–123. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Quinn SC. The contributions of health communication to eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(12):2053–2055. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC. Narratives and cancer communication. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:S163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC. Research challenges in narrative persuasion. Information Design Journal. 2008;16(1):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(5):701–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Brinn LS. Messages influencing college women’s tanning bed use: Statistical versus narrative evidence format and a self-assessment to increase perceived susceptibility. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:443–461. doi: 10.1080/713852118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte Y. The evidence in persuasive communication. Central St Speech Journal. 1976;27:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Heath C, Heath D. Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. New York, NY: Random House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34(5):777–792. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, Horn W, Holt CL, Trobaugh J, et al. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154:77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hydén LC. Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1997;19(1):48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Isay D. Listening is an act of love: A celebration of American Life from the StoryCorps Project. New York, NY: Penguin; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: a meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(4):388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA. Emotional memory across the adult lifespan. London, UK: Psychology Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Khangura S, Bennett C, Stacey D, O’Connor AM. Personal stories in publicly available patient decision aids. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73:456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Buskirk TD, Holmes K, Clark EM, Robinson L, Rath S, et al. What makes cancer survivor stories work? An empirical study among African American women. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(1):33–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, Slater MD, Wise ME, Storey D, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, et al. Comparing narrative and non-narrative communication to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81(S1):S6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Gonzalez J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer prevention and early detection among Latinos. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;67:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Lopez AM, Minnal A, Gonzalez J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: A randomized pilot study. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):79–87. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemal M, Van den Bulck J. Testing the effectiveness of a skin cancer narrative in promoting positive health behavior: A pilot study. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian M, Jeffe DB, Schootman M. Racial and geographic differences in mammography screening in St. Louis City: A multilevel study. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85(5):677–692. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9301-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon MS, Kazoleas DC. A comparison of exemplar and statistical evidence in reducing counter-arguments and responses to a message. Communication Research Reports. 2004;21(3):291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Maibach E, Flora JA. Symbolic modeling and cognitive rehearsal - Using video to promote AIDS prevention self-efficacy. Communication Research. 1993;20(4):517–545. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler JM, Johnson NS. Remembrance of things parsed: Story structure and recall. Cognitive Psychology. 1977;9:111–151. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ, Lindzey G, Aronson E. The handbook of social psychology. 3. New York, NY: Random House; 1985. Attitudes and attitude change; pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Kreuter MW. Women’s cognitive and affective reactions to breast cancer survivor stories: A structural equation analysis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81:S15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Vernon SW, Rothman AJ, Norman GJ, Myers RE, Tilley BC. Examining the role of perceived susceptibility on colorectal cancer screening intention and behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):205–217. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9215-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Guse E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory. 2008;18:407–425. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Guse E, Nabi RL. Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: Overcoming resistance to persuasion. Human Communication Research. 2010;36:26–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson RA, Kreuter MW, Lapka C, Wellborn R, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V, et al. Unintended effects of emphasizing disparities in cancer communication to African-Americans. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(11):2946–2953. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett R, Ross L. Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Petraglia J. Narrative intervention in behavior and public health. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12:493–505. doi: 10.1080/10810730701441371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Powe BD. Cancer fatalism among African-Americans: a review of the literature. Nursing Outlook. 1996;44:18–21. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(96)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts M, Shanteau J, McSpadden B, Fernandez-Medina KM. Using stories to battle unintentional injuries: Narratives in safety and health communication. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:1441–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskos-Ewoldsen DR, Fazio RH. The accessibility of source likability as a determinant of persuasion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(1):19–25. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer M, Rogers RW. The role of vivid information in fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Research in Personality. 1984;18(3):321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Simons HN, Berkowitz N, Moyer R. Similarity, credibility, and attitude change: A review and a theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1970;73(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative Impact: Social and Cognitive Foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory. 2002;12(2):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Thompson SC. Stalking the elusive “vividness” effect. Psychological Review. 1982;89(2):155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tiro JA, Diamond P, Perz CA, Fernandez ME, Rakowski W, Diclemente CC, et al. Validation of scales measuring attitudes and norms related to mammography screening in women veterans. Health Psychology. 2005;24(6):555–566. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Jepson C, Baron J. The inclusion of patient testimonials in decision aids: Effects on treatment choices. Medical Decision Making. 2001;21:60–68. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC. Development and validation of an instrument to measure factors related to colorectal cancer screening adherence. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 1997;6:825–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC, Li S. Factors associated with perceived risk in automotive employees at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2001;10:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeless LR, Grotz J. The measurement of trust and its relationship to self-disclosure. Human Communication Research. 1977;3(3):250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbottom A, Bekker HL, Conner M, Mooney A. Does narrative information bias individual’s decision-making? A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:2079–2088. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollinger TW, Champion VL, Monahan PO, Steele-Moses SK, Ziner KW, Zhao Q, et al. Effects of personal characteristics on African-American women’s beliefs about breast cancer. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2010;24(6):371–377. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07031727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]