Abstract

Multiple trajectories have recently been described through which hematopoietic progenitor cells travel prior to becoming lineage-committed effectors. A wide spectrum of transcription factors has recently been identified that modulate developmental progression along such trajectories. Here were describe how distinct families of transcription factors act and are linked together to orchestrate early hematopoiesis.

Keywords: Hematopoietic development, Lineage commitment, Genetic networks

1. Introduction

The differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells into the wide spectrum of mature cells is a well orchestrated and regulated process, controlled in large part by distinct sets of transcription factors. All of the cells of the immune system are derived from the long-term hematopoietic stem cell (LT-HSC)[1]. In the bone marrow, LT-HSCs have the ability to both self-renew and reconstitute the entire immune system for the life of the organism[2]. LT-HSCs can differentiate into short-term hematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSCs), which also maintain multipotency, but only have self-renewal capability for a limited time. ST-HSCs then differentiate into multipotent progenitors (MPPs), which are multipotent, but lack self-renewal capability[3, 4]. HSCs and MPPs express transcription factors from multiple lineages, commonly referred to as lineage priming[5–8]. This priming represents the developmental plasticity of early hematopoietic progenitors. Upon instructive cytokine signaling, the multipotent progenitors sequentially modulate the expression of genes encoding transcription factors that, in turn, activate the expression of lineage-specific genes and antagonize programs of gene expression associated with alternative cell lineages. Here, we describe how transcriptional networks modulate B, T and myeloid cell specification as well as genome-wide and computational approaches to describe early hematopoiesis in terms of global networks.

2. Lineage commitment in early hematopoiesis

Symmetric, self-renewing divisions of LT-HSCs occur rapidly in fetal development to ensure proper seeding of blood and immune compartments. However, in adults, LT-HSCs are often found in quiescent, not dividing states[9]. The self-renewal capability of these cells is maintained through complex regulation of multiple pathways, including the Notch and Wnt signaling pathways, Hox transcription factors, and the cell cycle regulators INK4A, INK4C, p21, p27, and PTEN[10, 11]. LT-HSCs are identified through the absence of cell surface markers of differentiated immune cells (lineage negative), and the presence of cKit, Sca1 (LSK), and CD150. Downregulation of CD150 marks differentiation into the ST-HSC and MPP, and a subsequent decline of self-renewal activity[12, 13]. Differentiation from the MPP into more committed progenitors was previously thought to proceed through a bifurcated pathway, with the B, T and natural killer (NK) cell lineages developing from the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) and the monocyte, granulocyte, megakaryocyte and erythroid lineages from the common myeloid progenitor (CMP)[3, 4]. This roadmap has been revised in recent years to include lymphoid primed multipotent progenitor (LMPP)[14]. In this scenario, MPPs have the ability to differentiate into the erythroid or megakaryocyte lineage through a pre-megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor (MEP), which expresses low to intermediate levels of CD105 and CD34 and low levels of CD41, or into the lymphoid/myeloid lineage through the LMPP, which is characterized by high levels of Flt3. While the MEP is restricted to a megakaryoctye or erythroid lineage, the LMPP has potential for B, T, NK, monocyte, and granulocyte lineages[12–17]. Antagonistic activities of the transcription factors GATA-1 and PU.1 effectively segregate the MEP from LMPP lineages, with GATA-1 directing development into MEPs and PU.1 promoting the LMPP fate[18–20].

Expression and signaling through the Flt3 tyrosine kinase receptor in LMPPs favors differentiation into the B or T lymphoid lineages[14]. The LMPP generates the lymphoid lineages through either an early T-cell progenitor (ETP) or a common lymphoid progenitor (CLP), or both[3, 27–29]. From the Lin−ScalowckitlowFlt3highIL7Rhigh CLP, early B-cell development proceeds through an ordered pathway beginning with the Ly6D positive B-primed lymphoid progenitor (BLP), then into a B220intCD43high pre-pro-B cell, a B220highCD19high pro-B cell, and finally into the CD25 positive pre-B cell[27, 30, 31]. Many of these early lineages are defined based on rearrangement of the antigen receptor genes IgH, IgK and IgL [32]. Rearrangement of the D–J fragments of the IgH gene has been documented as early as the CLP stage. Upon expression of CD19 at the pro-B cell stage, V-DJ rearrangement of IgH has been completed. Upon expression of the pre-B cell receptor, the cells then proliferate and differentiate to a CD25 positive pre-B cell stage, where rearrangement of the BCR light chain is initiated[27, 30–33].

T lineage specification arises through a Lin−ckit+CD44+CD25− ETP or double negative 1 (DN1) bone marrow derived thymic progenitor. ETPs, previously thought to be committed to the T-cell lineage, actually maintain myeloid, dendritic, and natural killer (NK) cell potential as shown by both in vitro and in vivo differentiation assays[34],[35]. T cell progression proceeds from the DN1to a Lin−ckit+CD44+CD25+ DN2, a Lin−ckit−CD44−CD25+ DN3 and a Lin−ckit−CD44−CD25− DN4 cell[36]. Recently, the DN2 stage has been subdivided into DN2a and DN2b on the basis of the expression of the T cell commitment factor, Bcl11b, and the DN3 stage has been subdivided into DN3a and DN3b on the basis of CD27 expression[37–40]. Full commitment to the T lineage occurs at the DN3a stage[41]. To proceed through the DN3 stage of commitment, burgeoning T cells must progress through a T cell receptor (TCR) checkpoint, where the cell must successful rearrange and express either the TCR-β and pre- Tα genes, or the γ and δ TCR loci[42],[43]. Expression of the TCR-β and pre-Tα genes, known as the pre-TCR, directs T cells to rapidly divide and differentiate to the CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) stage of T cell development[42]. It is during this stage that the pre-TCR signals to rearrange the TCR Vα and Jαsegments to complete mature TCR expression. From the DP compartment, T cells proceed to a CD4 or CD8 single positive stage before exiting the thymus[41].

The myeloid lineage develops through granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs), which can arise from either the LMPP or MPP compartments[14, 16]. LMPPs differentiate into the myeloid lineage through the FcγR positive granulocyte/macrophage progenitor (GMP), or into the lymphoid lineage through the IL7R positive common lymphoid progenitor (CLP)[15, 21, 22]. The GMP can be isolated based on cell surface expression of FCγR and CD34 within the LSK CD4low progenitor fraction[16, 23]. Further signaling through the macrophage colony stimulating factor receptor (MCSFR) or granulocyte-CSFR (GCSFR) by G-CSF, M-CSF and/or GM-CSF leads to changes in transcription factor expression and the delineation of the neutrophil or macrophage fate [24, 25]. Macrophages or neutrophils are specified from the GMP based on interactions of PU.1 with the CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (CEBPα, β, and ε), with high levels of the CEBPs defining granulopoiesis and high levels of PU.1 inducing macrophage development[26].

3. Regulation of gene expression in HSCs and multipotent progenitors

HSCs and multipotent progenitors balance their roles of self-renewal and maintenance of pluripotency. This is achieved through intricate networks of regulators whose activities and interactions are still poorly understood.

3.1 Transcriptional factors and HSC self-renewal

To maintain homeostasis of hematopoietic cells, HSCs must undergo divisions that ensure that one or both daughter cells remain in an undifferentiated state. In the mesoderm, the transcription factor SCL dimerizes with the E proteins to commence a hematopoietic program[44]. In the developing embryo, HSCs are primarily localized in the fetal liver whereas in the adult they are localized in the bone marrow. Recent studies have begun to identify components that promote HSC survival. For example, forced expression of the anti-apoptoptic factor Bcl2 increases HSC self-renewal and transplantation efficiency. In contrast, deletion of the anti-apoptosis factor Mcl1 leads to the complete failure of hematopoietic development, indicating its necessity for HSC’s survival [45].

The Hox family of transcription factors also plays a critical role in hematopoietic development and HSC self-renewal. The Hox genes were identified in Drosophila as regulators of body patterning pathways, and have since been shown to be required for mammalian hematopoiesis. The Hox proteins interact with the co-factor Meis1 to direct normal hematopoiesis[46]. Although multiple Hox genes are expressed in HSCs, Hoxa9 is expressed at very high levels[47]. Hoxa9 −/− mice exhibit multiple hematopoietic defects including the inability of Hoxa9−/− HSCs to properly reconstitute recipient animals [48]. In contrast, Hoxb4 deficient mice lack a dramatic hematopoietic phenotype even though overexpression of the Hoxb4 gene allows for increased self-renewal and expansion of HSCs in vitro[49].

The zinc-finger repressor protein Gfi1 (Growth factor independence 1) is also required for HSC self-renewal. Initially, roles for Gfi1 were identified both in T-cell development and T-cell lymphomas [50]. A role for Gfi1 in HSCs was confirmed by assays showing that HSCs from mice deficient for Gfi1 have increased rates of self-renewal and cannot effectively reconstitute animals in transplantation assays[51]. Gfi1 activates expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1, which is also required for normal hematopoiesis. However, p21 and Gfi1 knockouts have differing hematopoietic defects, indicating that although Gfi1 may act in part through regulation of p21, it must have other actions of HSC regulation as well[52]. Interestingly, recent work has connected the stress response to HSC self renewal by linking p53 activity and Gfi1 expression[53].

The polycomb group proteins (PcG) are critical for efficient HSC self-renewal. Specifically, Bmi1 is required for HSC homeostasis, as animals deficient for Bmi1 show a severely reduced self-renewal capacity and an increased rate of differentiation[54]. Correspondingly, overexpression of Bmi1 in HSCs leads to increased self-renewal in vitro and increased repopulating ability in vivo [54].

Signaling pathways that are active in controlling HSC self-renewal include the JAK-STAT pathway and Wnt signaling. Overexpression of the JAK activated transcription factor STAT5 leads to increased self-renewal and expansion of hematopoietic progenitors ex vivo, and HSCs from STAT5 knockout mice have a decreased ability to reconstitute irradiated recipients[55, 56]. Addition of Wnt proteins to culture media leads to increased self-renewal of HSCs in vitro, and HSCs expressing a constitutively active form of β-catenin exhibit improved self-renewal and reconstitution ability in vivo [57].

3.2 Lineage priming in HSCs and MPPs

HSCs express not only transcription factors that maintain their self-renewal capacity, but also transcription factors closely associated with the development of multiple lineages. This lineage priming is suggested to reflect the pluripotent capability of these cells[5, 58]. It has been shown that HSCs express many myeloid required transcription factors, including MPO, CEBPα, and MCSFR[6]. Erythroid and megakaryoctye required factors such as Gata1, EpoR and MPL are also expressed in the most primitive of bone marrow hematopoietic precursors[7]. Upon differentiation into MPPs and LMPPs, the mRNA levels of the erythroid specific genes decreases, while the levels of the myeloid transcription factors remain stable[7]. Appreciable expression of lymphoid specific genes such as preTα and Pax5 are not seen until the CLP stage. This suggests that the “default” lineages for the hematopoietic system leans toward the innate immune system, and that lineage commitment occurs upon both the upregulation and activation of a lineage specific gene network with the concomitant downregulation or suppression of transcription of genes associated with alternative cell lineages[6–8].

4. Genetic networks of B cell specification

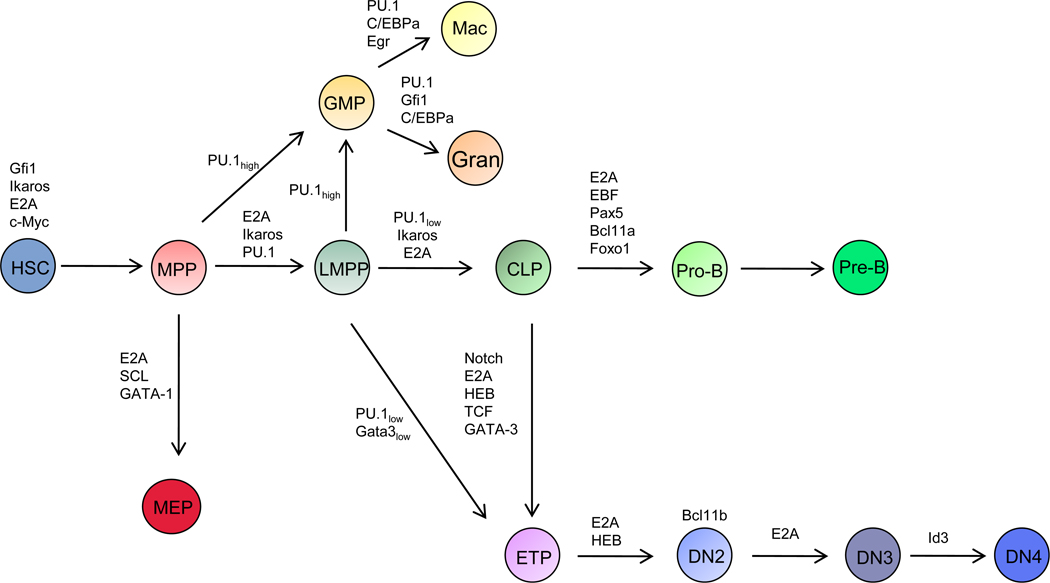

During the past two decades substantial insight has been obtained about the participants that promote the development of the B cell lineage and their concerted activities (Figure 1). The transcription factor Ikaros was among the first transcriptional regulators shown to play an important role in orchestrating lymphoid development. Ikaros is a Kruppel-like zinc finger protein that functions as a dimer or multimer to recruit either co-repressor or co-activator complexes such as the SWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling complex[59]. Ikaros −/− mice have defects in HSC self-renewal and lymphoid development beyond the LMPP cell stage[60]. Specifically, Ikaros −/− LMPPs fail to upregulate Flt3[60]. Thus, CLPs are absent in Ikaros ablated animals, leading to a block in B cell development and an increased potential for NK cell development[60]. Ikaros has also recently been shown to be necessary to allow V-DJ recombination in pro-B cells[61]. Specifically, infection of Ikaros−/− LSK progenitors with a retrovirus expressing EBF allows progression to the CD19+ B-cell stage, but is not sufficient to permit V-DJ recombination to occur. In fact, CD19+ EBF expressing Ikaros −/− cells can be diverted to the myeloid lineage upon appropriate cytokine stimulation[61]. Thus, Ikaros seems to play multiple roles in the development of B cells including: 1-the development of the CLP through regulation of Flt3 and, 2-the control of V-DJ rearrangement through regulation of the Rag recombinase genes and accessibility at the IgH locus[60, 61].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram indicating developmental trajectories in early hematopoiesis. Transcription factors that act at distinct steps in hematopoiesis are indicated. HSC refers to hematopoietic stem cell. MPP indicates multipotent progenitor. LMPP refers to lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor. GMP indicates the granulocyte-macrophage progenitor compartment. MEP indicates the premegakaryocytic/erythroid progenitor compartments. CLP refers to common lymphoid progenitor compartment. Gran refers to granulocytes. Mac indicates the macrophage compartment. ETP refers to early thymocyte progenitor.

It has been suggested that Ikaros regulates expression of Flt3 and IL7R in concert with PU.1[62]. PU.1 is an ETS family transcription factor that is required for development of both myeloid and lymphoid lineages[63]. PU.1 is expressed in HSCs, LMPPs, CLPs, myeloid and B cell progenitors, and in developing T, NK and dendritic cells[64]. Mice deficient for PU.1 die soon after birth and lack myeloid and lymphoid development, but show normal erythroid development[63]. PU.1 has specific roles in the bifurcation of the myeloid and B cell lineages. High levels of PU.1 enforce myeloid development, while low levels promote B-cell differentiation[65]. Control of this PU.1 gradient for B cell commitment appears to be through direct repression of PU.1 by Gfi1[66]. Gfi1−/− mice have reduced B cell potential, as the loss of the repression of PU.1 diverts cells to the myeloid lineage. Interestingly, Gfi1 transcription is regulated by Ikaros, suggesting a transcriptional loop to support B-cell development and repress the myeloid fate choice[66].

The E2A proteins are also implicated in the expression of the IL7Rα gene[67]. The E2A gene encodes two splice variants, E12 and E47, and is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix E protein family of transcription factors[68, 69]. In mice lacking the E2A gene, there is a complete block in B-cell development at the BLP stage before IgH D-J rearrangement has occurred[70, 71]. Recently, it has been shown that E2A plays a distinct role in the HSC and LMPP compartments, as there is a significant decrease in the numbers of HSCs and LMPPs in E2A heterozygous and knockout animals[21, 22, 72]. E2A also has specific roles in rearrangement of the heavy and light chain genes at the pro-B and pre-B stages of development[70, 73, 74]. Additionally, E2A directly binds and upregulates the transcription factor EBF1, Foxo1, Pax5, IRF4, IRF8 as well as other target B-cell genes, to activate a B-lineage program of gene activity[67, 75, 76]. Although E2A has a distinct role in positively promoting B-cell development, it also acts to suppress the expression of genes associated with alternative cell lineages[77]. E2A is inhibited by the Id proteins, which heterodimerize with E proteins at the helix-loop-helix domain to inhibit their ability to bind DNA[78].

The EBF transcription factor contains a HLH motif used for dimerization and an N-terminus zinc coordination motif that mediates DNA binding[79, 80]. Mice deficient for EBF have an almost identical block in B-cell development as the E2A −/− mice[81]. EBF −/− mice also fail to express B-cell specific genes, and do not have IgH rearrangement[81]. EBF is a transcriptional target of E2A and is sufficient to rescue B-cell development when expressed in E2A−/− progenitors[82]. Mice that are heterozygous for both E2A and EBF have more severe B-cell phenotypes than the single heterozygotes, suggesting a synergistic activity for E2A and EBF[83]. Recently, a synergistic relationship between Runx1 and EBF has also been shown to be critical to permit B-cell development, as the double heterozygous animals show defects in differentiation of CD25+ pre-B cells and stunted activation of B cell specific genes[84].

EBF is regulated by both a distal α promoter and a proximal β promoter [85]. The α promoter is active early in B-cell development both through direct E2A binding and indirect activity of STAT5, which is activated through the IL-7R. Additionally, there is an EBF binding site at the α promoter, suggesting that EBF is also regulated through an autoregulatory loop[75]. The β promoter is active in more mature B cell populations, and is activated by binding of Pax5, Ets1 and PU.1[85].

The transcription factor Pax5 is regulated by E2A, EBF, IRF4, IRF8 as well as PU.1. It plays an essential role in B-lineage commitment. Pax5 is only expressed in the B-cell lineage, where it is turned on in pro-B cells and remains on until the plasma cell stage[86]. B cell development is arrested in Pax5 −/− mice at the pro-B cell stage of development[87]. While EBF is required to induce the expression of Pax5, Pax5 induces the expression of EBF in a feedback loop[85, 88] It has recently become evident that both EBF and Pax5 act to promote commitment to the B cell lineage[89].

Pax5 can act both as a transcriptional activator and repressor. Consistent with these activities, Pax5 has been shown both to activate a B-cell specific program of gene expression while directly suppressing alternate lineage specific genes[90],[88]. Evidence suggests that Pax5 represses myeloid genes through antagonistic associations with the myeloid factor CEBPα[91]. In the absence of Pax5, pro-B cells maintain an unusual plasticity in that they can develop into myeloid cells and T cells[92].

Recently, additional transcription factors that play essential roles in B-cell development have been identified. Mice with B cell specific deletions of Foxo1 are arrested at the pro-B cell stage[93]. Specifically, Foxo1 was shown to be required for expression of IL-7R and Rag[94]. Furthermore, mice that are heterozygous for both E2A and Foxo1 have an almost complete absence of B cells[76]. Global patterns of Foxo1 occupancy in pro-B cells have indicated that E2A, EBF and Foxo1 act coordinately at enhancer elements to activate a B-lineage program of gene expression[76]. The Kruppel-related zinc finger protein Bcl11a is also required for B-lymphopoiesis. Mice deficient for Bcl11a have a block before pro-B cell commitment. Genetic analysis revealed that Bcl11a−/− fetal liver progenitors do not express IL7R, EBF, Pax5 or CD19, suggesting that Bcl11a may act in concert with E2A to initiate the B-cell fate[95, 96]. Additionally, the genome-wide studies described above have demonstrated that the E2A proteins bind to putative enhancer elements present in the Bcl11A locus[76].

5. Genetic networks of T cell specification

Unlike B-cell development, where a network of specific transcription factors initiates a B-lineage program of development which then leads to commitment of the B-lineage, T-cell specification is a gradual process of loss of other lineage choices until commitment is finalized at the DN3 stage[97, 98]. Progenitor cells expressing CCR9 preferentially home to the thymus, where Notch signaling initiates T lineage development[99]. There are four Notch glycoprotein receptors in mammals: Notch1–4. Notch1 appears to be particularly important for T-cell development. The ligands for the Notch receptors are the Delta-like (Dl) and Jagged proteins. Dl1 and Dl4 have the strongest capacity to initiate T-cell commitment in vitro[100]. Upon signaling, the Notch intracellular domain is cleaved and translocates to the nucleus where it acts as a transcriptional activator[100]. Notch signaling is sufficient for induction of the T cell program, as shown by the differentiation of uncommitted progenitors to mature single positive T cells simply by culturing in the presence of Dl1., Notch activity is required through β-selection[100],[101, 102]. However, Notch1 is not absolutely required for proper γδ lineage development[38, 103]. Notch signaling can be inhibited by LRF (Leukemia/Lymphoma Related Factor) and Mint (Msx2-interacting nuclear target) to modulate the levels of active Notch [100]. Mice deficient for LRF have extra-thymic production of T-cells in the bone marrow due to an inability to inhibit Notch signaling in bone marrow progenitors[104]. Initiation of the T-cell program through Notch signaling is at least partially due to Notch mediated upregulation of Tcf1 and Gata3[105]. Mice deficient for Tcf1 have a block at the DN1 to DN2 transition[106]. Gfi1 deficient thymocytes also have a similar block prior to the DN2 stage[107]. Interaction of Notch with the transcription factor RBJP (otherwise known as CSL) and/or with the E proteins E47 or HEB leads to upregulation of Notch target genes such as preTα, Hes1, CD25 and Notch-1 itself[36, 108]. Notch signaling can also act to inhibit the development of alternate lineages, but the precise mechanism by which Notch signaling acts to suppress the development of alternative cell lineages remains to be established[105].

Originally identified as key regulators of the B-cell fate, the ubiquitously expressed E proteins also have essential roles in T-cell development[109, 110]. E2A and HEB mRNA levels increase at the DN1 to DN2 transition[111]. Correspondingly, E2A−/− mice have a partial block at the DN1 stage[109, 112]. Overexpression of a dominant negative form of HEB leads to a similar block, indicating that heterodimers of E2A and HEB are active to promote T-lineage progression[109, 113]. E47 has been identified to act synergistically with Notch signaling to both activate T-cell specific genes such as pTα and Hes1, as well as to repress myeloid and NK development[36]. Furthermore, E2A can directly regulate TCRβ V(D)J gene rearrangements[114]. E2A also regulates Notch transcription, and it is proposed that signaling through the pre-TCR activates the E protein inhibitor Id3, and the subsequent loss of E2A activity is responsible for the sharp downregulation of Notch mRNA after the DN3 stage[115]. Genetic studies have demonstrated that high levels of E2A activity enforce the pre-TCR checkpoint whereas low E2A abundance promotes β-selection109.

The abundance of the zinc-finger transcription factor Gata3 is gradually elevated after the commencement of Notch signaling, and is required both at the onset of T-lineage commitment, the β-selection checkpoint and to promote CD4 SP differentiation[111, 116]. In the absence of Gata3, T-cell development is blocked before the DN cell stage[117]. However, upon forced Gata3 expression, T-cell development is blocked and diverted to the mast cell lineage, displaying a sensitive dosage requirement for Gata3[118]. Not only is the dosage of Gata3 important in T-cell development, but the proper balance of Gata3 and PU.1 expression appears to be critical. As discussed, PU.1 is required in B, myeloid and T lineage commitment. Similar to Gata3, T cell development is blocked before the DN stage of development in the absence of PU.1[119]. Also similar to Gata3, upon forced PU.1 expression in early T progenitors, T-cell development is blocked and an alternate myeloid lineage develops[120]. PU.1 expression is high in DN1 cells, but is downregulated as cells proceed to T-lineage commitment at the DN3 stage[108, 111]. Since the expression patterns of Gata3 and PU.1 oppose each other (Gata3 levels increase as PU.1 levels decrease), it has been suggested that PU.1 and Gata3 act antagonistically to control the dosage of each other. However, overexpression experiments and careful analysis of PU.1 and Gata3 expression levels, as well as their target genes, suggests that the two proteins probably do not directly antagonize each other, rather, Notch signaling may act to control the activities of both gene products[108, 121].

There is also evidence that PU.1 is directly regulated in the T-lineage by Runx1[122]. Runx1 is absolutely required for hematopoietic development in the fetus, and conditional ablation of Runx1 showed that it is essential at multiple stages in T-cell development[116, 123]. Conditional Runx1 knockout mice have an incomplete block at the DN2 to DN3 transition, indicating that Runx1 is required for proper T-lineage commitment[123–125]. There is also a marked effect of Runx1on both the generation of ETPs and the ETP to DN2 transition[123]. In mice deficient for Runx1, PU.1 levels are substantially higher in the accumulated DN2 cells. However, the block in the DN2 to DN3 transition is partially repaired in Runx1−/−PU.1+/− mice, suggesting that at least part of the requirement for Runx1 in T-cell development is to properly regulate PU.1[122].

In a series of elegant experiments, Bcl11b has recently been shown to promote T cell commitment[37, 39, 40]. Bcl11b deficient ETPs, when cultured on OP9- DL1 stroma cells, were completely blocked at the DN2 stage. Interestingly, in the absence of Bcl11b, the expression of genes normally downregulated at this stage, including Id2, Il2rb, Tal1 and the IL7, Flt3, and cKit receptors were not appropriately suppressed[37, 39]. Furthermore, in the absence of Bcl11b, developing thymocytes remained multipotent and showed a remarkable ability to differentiate into NK or myeloid cells. Thus, these recent studies demonstrate a critical role for Bcl11b in T-lineage development. Although T-cell specification begins upon arrival in the thymus and activation of Notch signaling pathways, absolute commitment of the T-cell lineage does not occur until Bcl11b expression at the DN3 transition. Bcl11b levels are regulated both by Notch and IL7R signaling to specify a T-cell versus myeloid or NK cell fate, linking Notch1, IL7 mediated signaling and Bcl11b into a common pathway[39, 40]. Finally, in multipotent progenitors, Bcl11b as well as GATA3 expression is suppressed by E47 activities[36]. We suggest that the E2A proteins may act during development to suppress the expression of these key factors in developing B cells as well as fine-tune the expression levels in developing thymocytes. Using global binding studies in conjunction with computational approaches it should be possible to gain further insight into how they are linked together to orchestrate the T cell fate.

6. Genetic networks of myeloid specification

Among the factors that modulate myeloid development, the ETS domain containing protein PU.1, has probably been the most extensively studied (Figure 1). PU.1 expression in early hematopoietic progenitors is induced by Runx1, which binds to a regulatory element located in the PU.1 locus[122]. As mentioned before, high levels of PU.1 in LMPPs promote myeloid lineage specification at the expense of B-cell development[65]. Two recent reports show extensive binding of PU.1 to macrophage specific enhancers, confirming the role of PU.1 in directly regulating a macrophage specific program of gene expression [126, 127]. PU.1 interferes with erythroid development by directly inhibiting the activity of the erythroid specific factor Gata1[18]. In addition, PU.1, in conjunction with CEBPα, controls the macrophages versus neutrophil lineage choice (Figure 1). In GMPs, activation of PU.1 leads to upregulation of the Egr/Nab factors which act as a secondary determinant of macrophage fate by further activating the expression of macrophage specific genes and repressing the expression of genes associated with a neutrophil specific program of gene expression[128]. The Egr/Nab factors inhibit Gfi1, which is induced by CEBPα and which represses macrophage specific genes in concert with CEBPα to promote neutrophil differentiation[128]. In fact, Gfi1−/− animals lack neutrophils, and Egr1−/−Egr2+/− mice show severe defects in macrophage generation. From these observations a regulatory network, involving PU.1, CEBPα, Gfi1 and the Erg/Nab genes has been generated and has been proposed to orchestrate the macrophage versus granulocytic cell fate[128–130]. Conditional deletion of CEBPα interferes with myeloid development prior to the GMP cell stage and leads to a loss of granulocyte development[131, 132]. At least part of this block can be attributed to direct regulation of the MCSF and GCSF receptors by CEBPα[131, 133]. CEBPβ and CEBPε are also critical factors in myeloid cell development, as mice deficient for CEBPβ show reduced generation of myeloid cells, and mice deficient for CEBPε exhibit reduced numbers of both macrophages and granucocytes[134, 135]. There may be some redundancy in the CEBP family, as transcription of the CEBPβ gene from the CEBPα promoter rescues macrophage development. However macrophage function is not completely restored by CEBPα [136]. CEBPα transcripts are present in HSCs, LMPPs and GMPs, but not in erythroid lineage precursors [26]. Strikingly, overexpression of CEBPα is sufficient to reprogram pro-T cells or CD19+ B cells into cells that express a myeloid specific transcript signature[120, 137, 138]. Recent studies have indicated that CEBPα acts to reprogram T cells into a myeloid cell fate through direct or indirect antagonism of Notch signaling as well as GATA3 expression[120]. Similarly, Pax5 has been demonstrated to repress a myeloid specific program of gene expression in developing B cell progenitors by inhibiting C/EBPα expression.

7. Global patterns of genome-wide DNA binding and early hematopoiesis

During early hematopoiesis, developmental pathways with multiple branch points from which progenitor cells give rise to multiple hematopoietic lineages have been specified. Transcription factors critical to these pathways have been identified to characterize and modulate both the developmental progression and expansion and survival of early progenitors. However, it remains largely unknown as to how these transcription factors are linked to promote lineage- and stage-specific phenotypes. Recent studies using ChIP-Seq approaches, along with new computational analyses like HOMER (Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment), have provided mechanistic insight into how myeloid- and B-lineage specification is established at a global scale.

As discussed above, the activities of PU.1 are critical to promote both myeloid- and B-lineage specification. Recent genome-wide studies demonstrate how PU.1 acts at a global scale to modulate lineage choice[35, 126, 127]. In myeloid cells, PU.1 binding was primarily associated with consensus binding sites for AP-1 and C/EBP. In contrast, promoter-distal PU.1 occupancy in B-lineage cells was predominantly enriched at genomic regions containing promoter-distal E2A, PU.1:IRF, EBF, NFκB, and OCT consensus binding sites. In both myeloid and B cells, PU.1 genome-wide occupancy was predominantly detected at promoter-distal sites, and was tightly correlated with myeloid- and B-lineage specific programs of gene expression, respectively.

Similar studies have been performed studying E2A occupancy at the genome-wide scale[76]. In pre-pro-B cells, enhancer elements associated with E2A occupancy were significantly enriched for RUNX and ETS consensus binding sites. In contrast, in pro-B cells, E2A bound sites were primarily associated with ETS, EBF, RUNX, and Foxo1 binding sites. Furthermore, Foxo1 and EBF ChIP-Seq experiments show that coordinate E2A, EBF and Foxo1 DNA binding sites were closely correlated with a B-lineage program of gene expression. Similar ChIP-Seq studies that analyzed only EBF1 binding showed a significant enrichment for the ETS, E2A, EBF1 and Pax5 binding sites[139]. In the latter study, it was observed that EBF1 occupancy showed a tendency to associate with components involved in pre-BCR mediated signaling.

These studies have generated a global network of transcription factors proposed to orchestrate the B cell fate. Briefly, analysis suggests that in progenitor cells, the E2A proteins directly induce the expression of EBF1, IRF4, IRF8 and Foxo1[76]. Additionally, E2A may regulate the expression of Pax5 through multiple circuitries. Previous studies have indicated that IRF4, IRF8 and PU.1 act to induce the expression of Pax5[140]. The E2A proteins directly interact with putative enhancer localized within the Pax5 locus, but they also modulate Pax5 transcription by the induction of Foxo1, Ebf1, IRF4 and IRF8 expression[76].

The construction of a network that underpins specification of the B cell lineage also revealed new connections[76]. E2A was found to directly bind enhancers present in the Bcl11A and CTCF loci, linking E2A, Bcl11A, and potentially CTCF into a common pathway. During developmental progression from the pre-pro-B to the pro-B cell stage, the IgH locus undergoes large-scale conformational changes, and it is conceivable that the activation of CTCF expression contributes to IgH locus contraction[141, 142]. It was also demonstrated that E2A and Foxo1 directly bind to potential regulatory elements present in the LEF1 locus[76]. The LEF proteins have been shown to act downstream of the Wnt signaling pathway and modulate B cell expansion, thus linking E2A, Foxo1 and Wnt signaling into a common pathway[143]. The suppression of genes associated with alternate cell lineages was also found to be associated with differing combinations of E2A, EBF and/or Foxo1 occupancy. Among these genes are regulators that play critical roles in early hematopoeisis including CEBPα, Notch1, RUNX2, RUNX3 and GATA3[76]. These data raise the question as to how E2A, EBF and Foxo1 act to either activate or inhibit the expression of genes. We suggest that this is dependent on the context of the regulatory elements to which they bind. It is conceivable that the spatial arrangement of various cis-regulatory elements determines the outcome of combinatorial interactions to either activate or suppress downstream target gene expression.

8. Conclusion

Genome-wide DNA binding studies of transcriptional regulators and global patterns of gene expression have provided new insights into how hematopoietic development is orchestrated. New players were identified and new connections have been revealed. These approaches are only a first step. The global DNA binding patterns of other transcriptional regulators that play critical roles in orchestrating lineage choice, including Pax5, PU.1, IRF4, IRF8, Bcl11A, LEF etc. need to be incorporated. Further studies should be combined with gene-ablation strategies performed at specific developmental stages. Better strategies to assign regulatory elements to specific loci need to be developed. This will require further insights into chromosome structure and how this relates to long-range genomic interactions. We are just at the beginning of gaining insight into the global mechanisms that underpin developmental progression and lineage choice.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Murre laboratory and Kristina Beck for critical reading of the manuscript. EMM was supported by a training grant (T32 DK007541). YCL was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Research Service Award (1F32CA130276). Research in the Murre laboratory is supported by the NIH (RAI082850A; RCA078384C).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weissman IL. Stem Cells: Units of Development, Units of Regeneration, and Units in Evolution. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spangrude G, Heimfeld S, Weissman I. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of Clonogenic Common Lymphoid Progenitors in Mouse Bone Marrow. Nat Immunol. 1997;91:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu M, Krause D, Greaves M, Sharkis S, Dexter M, Heyworth C, et al. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes & Development. 1997;11:774–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamoto T, Iwasaki H, Reizis B, Ye M, Graf T, Weissman IL, et al. Myeloid or Lymphoid Promiscuity as a Critical Step in Hematopoietic Lineage Commitment. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Månsson R, Hultquist A, Luc S, Yang L, Anderson K, Kharazi S, et al. Molecular Evidence for Hierarchical Transcriptional Lineage Priming in Fetal and Adult Stem Cells and Multipotent Progenitors. Immunity. 2007;26:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwasaki H, Mizuno S-i, Arinobu Y, Ozawa H, Mori Y, Shigematsu H, et al. The order of expression of transcription factors directs hierarchical specification of hematopoietic lineages. Genes & Development. 2006;20:3010–3021. doi: 10.1101/gad.1493506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1068–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature04956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsiftsoglou AS, Bonovolias ID, Tsiftsoglou SA. Multilevel targeting of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis for leukemia therapy. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;122:264–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zon LI. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of haematopoietic stem-cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature07038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papathanasiou P, Attema JL, Karsunky H, Xu J, Smale ST, Weissman IL. Evaluation of the Long-Term Reconstituting Subset of Hematopoietic Stem Cells with CD150. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2498–2508. doi: 10.1002/stem.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz ÖH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM Family Receptors Distinguish Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells and Reveal Endothelial Niches for Stem Cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adolfsson J, Månsson R, Buza-Vidas N, Hultquist A, Liuba K, Jensen CT, et al. Identification of Flt3+ Lympho-Myeloid Stem Cells Lacking Erythro-Megakaryocytic Potential: A Revised Road Map for Adult Blood Lineage Commitment. Cell. 2005;121:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murre C. Developmental trajectories in early hematopoiesis. Genes & Development. 2009;23:2366–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronk CJH, Rossi DJ, Månsson R, Attema JL, Norddahl GL, Chan CKF, et al. Elucidation of the Phenotypic, Functional, and Molecular Topography of a Myeloerythroid Progenitor Cell Hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai AY, Kondo M. Asymmetrical lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1867–1873. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rekhtman N, Radparvar F, Evans T, Skoultchi AI. Direct interaction of hematopoietic transcription factors PU.1 and GATA-1: functional antagonism in erythroid cells. Genes & Development. 1999;13:1398–1411. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew CW, Rand KD, Simpson RJY, Yung WW, Mansfield RE, Crossley M, et al. Molecular Analysis of the Interaction between the Hematopoietic Master Transcription Factors GATA-1 and PU.1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:28296–28306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang P, Behre G, Pan J, Iwama A, Wara-aswapati N, Radomska HS, et al. Negative cross-talk between hematopoietic regulators: GATA proteins repress PU.1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8705–8710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dias S, Månsson R, Gurbuxani S, Sigvardsson M, Kee BL. E2A Proteins Promote Development of Lymphoid-Primed Multipotent Progenitors. Immunity. 2008;29:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semerad CL, Mercer EM, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Murre C. E2A proteins maintain the hematopoietic stem cell pool and promote the maturation of myelolymphoid and myeloerythroid progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:1930–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buza-Vidas Nab, Luc Sbc, Jacobsen SEWac. Delineation of the earliest lineage commitment steps of haematopoietic stem cells: new developments, controversies and major challenges [Miscellaneous Article] Current Opinion in Hematology. 2007 July;14(4):315–321. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3281de72bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cecchini MG, Dominguez MG, Mocci S, Wetterwald A, Felix R, Fleisch H, et al. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Development. 1994;120:1357–1372. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barreda DR, Hanington PC, Belosevic M. Regulation of myeloid development and function by colony stimulating factors. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2004;28:509–554. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman AD. Transcriptional control of granulocyte and monocyte development. Oncogene. 2007;26:6816–6828. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borghesi L, Hsu L-Y, Miller JP, Anderson M, Herzenberg L, Herzenberg L, et al. B Lineage specific Regulation of V(D)J Recombinase Activity Is Established in Common Lymphoid Progenitors. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;199:491–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wada H, Masuda K, Satoh R, Kakugawa K, Ikawa T, Katsura Y, et al. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature. 2008;452:768–772. doi: 10.1038/nature06839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell JJ, Bhandoola A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature. 2008;452:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature06840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inlay MA, Bhattacharya D, Sahoo D, Serwold T, Seita J, Karsunky H, et al. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes & Development. 2009;23:2376–2381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1836009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansson R, Zandi S, Welinder E, Tsapogas P, Sakaguchi N, Bryder D, et al. Single-cell analysis of the common lymphoid progenitor compartment reveals functional and molecular heterogeneity. Blood. 2010;115:2601–2609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Alt FW. Gene rearrangement and B-cell development. Current Opinion in Immunology. 1993;5:194–200. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90004-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melchers F, Haasner D, Grawunder U, Kalberer C, Karasuyama H, Winkler T, et al. Roles of IGH and L Chains and of Surrogate H and L Chains in the Development of Cells of the B Lymphocyte Lineage. Annual Review of Immunology. 1994;12:209–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benz C, Bleul CC. A multipotent precursor in the thymus maps to the branching point of the T versus B lineage decision. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202:21–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinzel K, Benz C, Martins VC, Haidl ID, Bleul CC. Bone Marrow-Derived Hemopoietic Precursors Commit to the T Cell Lineage Only after Arrival in the Thymic Microenvironment. J Immunol. 2007;178:858–868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Goldrath AW, Murre C. E proteins and Notch signaling cooperate to promote T cell lineage specification and commitment. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1329–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Leid M, Rothenberg EV. An Early T Cell Lineage Commitment Checkpoint Dependent on the Transcription Factor Bcl11b. Science. 2010;329:89–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1188989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taghon T, Yui MA, Pant R, Diamond RA, Rothenberg EV. Developmental and Molecular Characterization of Emerging beta- and gammadelta-Selected Pre-T Cells in the Adult Mouse Thymus. Immunity. 2006;24:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikawa T, Hirose S, Masuda K, Kakugawa K, Satoh R, Shibano-Satoh A, et al. An Essential Developmental Checkpoint for Production of the T Cell Lineage. Science. 2010;329:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1188995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li P, Burke S, Wang J, Chen X, Ortiz M, Lee S-C, et al. Reprogramming of T Cells to Natural Killer-Like Cells upon Bcl11b Deletion. Science. 2010;329:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1188063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yui MA, Feng N, Rothenberg EV. Fine-Scale Staging of T Cell Lineage Commitment in Adult Mouse Thymus. J Immunol. 2010;185:284–293. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taghon T, Rothenberg E. Molecular mechanisms that control mouse and human TCR-αÎ2 and TCR-Î3δ T cell development. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2008;30:383–398. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livak F, Tourigny M, Schatz DG, Petrie HT. Characterization of TCR Gene Rearrangements During Adult Murine T Cell Development. J Immunol. 1999;162:2575–2580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Endoh M, Ogawa M, Orkin S, Nishikawa S-i. SCL/tal-1-dependent process determines a competence to select the definitive hematopoietic lineage prior to endothelial differentiation. Embo J. 2002;21:6700–6708. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Opferman JT, Iwasaki H, Ong CC, Suh H, Mizuno S-i, Akashi K, et al. Obligate Role of Anti-Apoptotic MCL-1 in the Survival of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Science. 2005;307:1101–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1106114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu Y-L, Fong S, Ferrell C, Largman C, Shen W-F. HOXA9 Modulates Its Oncogenic Partner Meis1 To Influence Normal Hematopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5181–5192. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00545-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK. Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6766–6776. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawrence HJ, Christensen J, Fong S, Hu Y-L, Weissman I, Sauvageau G, et al. Loss of expression of the Hoxa-9 homeobox gene impairs the proliferation and repopulating ability of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2005;106:3988–3994. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bijl J, Thompson A, Ramirez-Solis R, Krosl J, Grier DG, Lawrence HJ, et al. Analysis of HSC activity and compensatory Hox gene expression profile in Hoxb cluster mutant fetal liver cells. Blood. 2006;108:116–122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilks CB, Bear SE, Grimes HL, Tsichlis PN. Progression of interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent rat T cell lymphoma lines to IL-2-independent growth following activation of a gene (Gfi-1) encoding a novel zinc finger protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1759–1768. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng H, Yucel R, Kosan C, Klein-Hitpass L, Moroy T. Transcription factor Gfi1 regulates self-renewal and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Embo J. 2004;23:4116–4125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foudi A, Hochedlinger K, Van Buren D, Schindler JW, Jaenisch R, Carey V, et al. Analysis of histone 2B-GFP retention reveals slowly cycling hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Biotech. 2009;27:84–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y, Elf SE, Miyata Y, Sashida G, Liu Y, Huang G, et al. p53 Regulates Hematopoietic Stem Cell Quiescence. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwama A, Oguro H, Negishi M, Kato Y, Morita Y, Tsukui H, et al. Enhanced Self-Renewal of Hematopoietic Stem Cells Mediated by the Polycomb Gene Product Bmi-1. Immunity. 2004;21:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kato Y, Iwama A, Tadokoro Y, Shimoda K, Minoguchi M, Akira S, et al. Selective activation of STAT5 unveils its role in stem cell self-renewal in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202:169–179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snow JW, Abraham N, Ma MC, Abbey NW, Herndier B, Goldsmith MA. STAT5 promotes multilineage hematolymphoid development in vivo through effects on early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2002;99:95–101. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prohaska SS, Scherer DC, Weissman IL, Kondo M. Developmental plasticity of lymphoid progenitors. Seminars in Immunology. 2002;14:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s1044532302000726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Georgopoulos K, Moore D, Derfler B. Ikaros, an early lymphoid-specific transcription factor and a putative mediator for T cell commitment. Science. 1992;258:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1439790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nichogiannopoulou A, Trevisan M, Neben S, Friedrich C, Georgopoulos K. Defects in Hemopoietic Stem Cell Activity in Ikaros Mutant Mice. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;190:1201–1214. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reynaud D, A Demarco I, L Reddy K, Schjerven H, Bertolino E, Chen Z, et al. Regulation of B cell fate commitment and immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangements by Ikaros. 2008;9:927–936. doi: 10.1038/ni.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeKoter RP, Lee H-J, Singh H. PU.1 Regulates Expression of the Interleukin-7 Receptor in Lymphoid Progenitors. Immunity. 2002;16:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott E, Simon M, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nutt SL, Metcalf D, D'Amico A, Polli M, Wu L. Dynamic regulation of PU.1 expression in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:221–231. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeKoter RP, Singh H. Regulation of B Lymphocyte and Macrophage Development by Graded Expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288:1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spooner CJ, Cheng JX, Pujadas E, Laslo P, Singh H. A Recurrent Network Involving the Transcription Factors PU.1 and Gfi1 Orchestrates Innate and Adaptive Immune Cell Fates. Immunity. 2009;31:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kee BL, Murre C. Induction of Early B Cell Factor (EBF) and Multiple B Lineage Genes by the Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor E12. J Exp Med. 1998;188:699–713. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-Loop-Helix Proteins: Regulators of Transcription in Eucaryotic Organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bain G, Maandag ECR, Izon DJ, Amsen D, Kruisbeek AM, Weintraub BC, et al. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell. 1994;79:885–892. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhuang Y, Soriano P, Weintraub H. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell. 1994;79:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Q, Kardava L, St. Leger A, Martincic K, Varnum-Finney B, Bernstein ID, et al. E47 Controls the Developmental Integrity and Cell Cycle Quiescence of Multipotential Hematopoietic Progenitors. J Immunol. 2008;181:5885–5894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beck K, Peak MM, Ota T, Nemazee D, Murre C. Distinct roles for E12 and E47 in B cell specification and the sequential rearrangement of immunoglobulin light chain loci. J Exp Med. 2009:2271–2284. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chowdhury D, Sen R. Regulation of immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangements. Immunological Reviews. 2004;200:182–196. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith EMK, Gisler R, Sigvardsson M. Cloning and Characterization of a Promoter Flanking the Early B Cell Factor (EBF) Gene Indicates Roles for E-Proteins and Autoregulation in the Control of EBF Expression. J Immunol. 2002;169:261–270. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin YC, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, Heinz S, Welinder E, Mansson R, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Wright LYT, Murre C. Long-Term Cultured E2A-Deficient Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells Are Pluripotent. Immunity. 2004;20:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: A negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hagman J, Belanger C, Travis A, Turck CW, Grosschedl R. Cloning and functional characterization of early B-cell factor, a regulator of lymphocyte-specific gene expression. Genes & Development. 1993;7:760–773. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hagman J, Lukin K. Early B-cell factor [`]pioneers' the way for B-cell development. Trends in Immunology. 2005;26:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin HH, Grosschedl R. Failure of B-Cell Differentiation in Mise Lacking the Transcription Factor Ebf. Nature. 1995;376:263–267. doi: 10.1038/376263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seet CS, Brumbaugh RL, Kee BL. Early B Cell Factor Promotes B Lymphopoiesis with Reduced Interleukin 7 Responsiveness in the Absence of E2A. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1689–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O'Riordan M, Grosschedl R. Coordinate Regulation of B Cell Differentiation by the Transcription Factors EBF and E2A. Immunity. 1999;11:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lukin K, Fields S, Lopez D, Cherrier M, Ternyak K, RamÃrez J, et al. Compound haploinsufficiencies of Ebf1 and Runx1 genes impede B cell lineage progression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:7869–7874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roessler S, Gyory I, Imhof S, Spivakov M, Williams RR, Busslinger M, et al. Distinct Promoters Mediate the Regulation of Ebf1 Gene Expression by Interleukin-7 and Pax5. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:579–594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fuxa M, Busslinger M. Reporter gene insertions reveal a strictly B lymphoid-specific expression pattern of Pax5 in support of its B cell identity function (vol 178, pg 3031, 2007) Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:8221–8228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nutt SL, Heavey B, Rolink AG, Busslinger M. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature. 1999;401:556–562. doi: 10.1038/44076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pridans C, Holmes ML, Polli M, Wettenhall JM, Dakic A, Corcoran LM, et al. Identification of Pax5 Target Genes in Early B Cell Differentiation. J Immunol. 2008;180:1719–1728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maier H, Hagman J. Roles of EBF and Pax-5 in B lineage commitment and development. Seminars in Immunology. 2002;14:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s1044532302000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cobaleda C, Schebesta A, Delogu A, Busslinger M. Pax5: the guardian of B cell identity and function. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:463–470. doi: 10.1038/ni1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsu C-L, King-Fleischman AG, Lai AY, Matsumoto Y, Weissman IL, Kondo M. Antagonistic effect of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-a and Pax5 in myeloid or lymphoid lineage choice in common lymphoid progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:672–677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cobaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature B cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dengler HS, Baracho GV, Omori SA, Bruckner S, Arden KC, Castrillon DH, et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Amin RH, Schlissel MS. Foxo1 directly regulates the transcription of recombination-activating genes during B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:613–622. doi: 10.1038/ni.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu P, Keller JR, Ortiz M, Tessarollo L, Rachel RA, Nakamura T, et al. Bcl11a is essential for normal lymphoid development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:525–532. doi: 10.1038/ni925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Medina KL, Singh H. Genetic networks that regulate B lymphopoiesis. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2005:203–209. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000160735.67596.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Medina KL, Pongubala JMR, Reddy KL, Lancki DW, DeKoter R, Kieslinger M, et al. Assembling a Gene Regulatory Network for Specification of the B Cell Fate. Developmental Cell. 2004;7:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carpenter AC, Bosselut R. Decision checkpoints in the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:666–673. doi: 10.1038/ni.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sambandam A, Maillard I, Zediak VP, Xu L, Gerstein RM, Aster JC, et al. Notch signaling controls the generation and differentiation of early T lineage progenitors. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:663–670. doi: 10.1038/ni1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Ohtani T, Pear WS. Notch regulation of early thymocyte development. Seminars in Immunology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.015. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schmitt TM, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Induction of T Cell Development from Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells by Delta-like-1 In Vitro. Immunity. 2002;17:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Ohtani T, Pear WS. Notch regulation of early thymocyte development. Seminars in Immunology Molecular and Cellular Basis of T cell Lineage Commitment. 2010;22:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Garbe AI, von Boehmer H. TCR and Notch synergize in alphabeta versus gammadelta lineage choice. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maeda T, Merghoub T, Hobbs RM, Dong L, Maeda M, Zakrzewski J, et al. Regulation of B Versus T Lymphoid Lineage Fate Decision by the Proto-Oncogene LRF. Science. 2007;316:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1140881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Taghon TN, David E-S, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Rothenberg EV. Delayed, asynchronous, and reversible T-lineage specification induced by Notch/Delta signaling. Genes & Development. 2005;19:965–978. doi: 10.1101/gad.1298305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Verbeek S, Izon D, Hofhuis F, Robanusmaandag E, Teriele H, Vandewetering M, et al. An Hmg-Box-Containing T-Cell Factor Required for Thymocyte Differentiation. Nature. 1995;374:70–74. doi: 10.1038/374070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yucel R, Karsunky H, Klein-Hitpass L, Moroy T. The Transcriptional Repressor Gfi1 Affects Development of Early, Uncommitted c-Kit+ T Cell Progenitors and CD4/CD8 Lineage Decision in the Thymus. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197:831–844. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Georgescu C, Longabaugh WJR, Scripture-Adams DD, David-Fung E-S, Yui MA, Zarnegar MA, et al. A gene regulatory network armature for T lymphocyte specification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:20100–20105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806501105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bain G, Engel I, Robanus Maandag E, te Riele H, Voland J, Sharp L, et al. E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in alphabeta T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4782–4791. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.David-Fung E-S, Butler R, Buzi G, Yui MA, Diamond RA, Anderson MK, et al. Transcription factor expression dynamics of early T-lymphocyte specification and commitment. Developmental Biology. 2009;325:444–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Engel I, Johns C, Bain G, Rivera RR, Murre C. Early Thymocyte Development Is Regulated by Modulation of E2A Protein Activity. J Exp Med. 2001;194:733–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Barndt RJ, Dai M, Zhuang Y. Functions of E2A-HEB Heterodimers in T-Cell Development Revealed by a Dominant Negative Mutation of HEB. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6677–6685. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6677-6685.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Agata Y, Tamaki N, Sakamoto S, Ikawa T, Masuda K, Kawamoto H, et al. Regulation of T Cell Receptor [beta] Gene Rearrangements and Allelic Exclusion by the Helix-Loop-Helix Protein, E47. Immunity. 2007;27:871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yashiro-Ohtani Y, He Y, Ohtani T, Jones ME, Shestova O, Xu L, et al. Pre-TCR signaling inactivates Notch1 transcription by antagonizing E2A. Genes & Development. 2009;23:1665–1676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1793709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rothenberg EV, Moore JE, Yui MA. Launching the T-cell-lineage developmental programme. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:9–21. doi: 10.1038/nri2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ting CN, Olson MC, Barton KP, Leiden JM. Transcription factor GATA-3 is required for development of the T-cell lineage. Nature. 1996;384:474–478. doi: 10.1038/384474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Taghon T, Yui MA, Rothenberg EV. Mast cell lineage diversion of T lineage precursors by the essential T cell transcription factor GATA-3. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:845–855. doi: 10.1038/ni1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Spain LM, Guerriero A, Kunjibettu S, Scott EW. T Cell Development in PU.1-Deficient Mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:2681–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Xie H, de Andres-Aguayo L, Graf T. Reprogramming of Committed T Cell Progenitors to Macrophages and Dendritic Cells by C/EBP[alpha] and PU.1 Transcription Factors. Immunity. 2006;25:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Franco CB, Scripture-Adams DD, Proekt I, Taghon T, Weiss AH, Yui MA, et al. Notch/Delta signaling constrains reengineering of pro-T cells by PU.1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:11993–11998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601188103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huang G, Zhang P, Hirai H, Elf S, Yan X, Chen Z, et al. PU.1 is a major downstream target of AML1 (RUNX1) in adult mouse hematopoiesis. 2008;40:51–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Talebian L, Li Z, Guo Y, Gaudet J, Speck ME, Sugiyama D, et al. T-lymphoid, megakaryocyte, and granulocyte development are sensitive to decreases in CBF{beta} dosage. Blood. 2007;109:11–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Growney JD, Shigematsu H, Li Z, Lee BH, Adelsperger J, Rowan R, et al. Loss of Runx1 perturbs adult hematopoiesis and is associated with a myeloproliferative phenotype. Blood. 2005;106:494–504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kawazu M, Asai T, Ichikawa M, Yamamoto G, Saito T, Goyama S, et al. Functional Domains of Runx1 Are Differentially Required for CD4 Repression, TCR{beta} Expression, and CD4/8 Double-Negative to CD4/8 Double-Positive Transition in Thymocyte Development. J Immunol. 2005;174:3526–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, et al. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ghisletti S, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Polletti S, De Santa F, Venturini E, et al. Identification and Characterization of Enhancers Controlling the Inflammatory Gene Expression Program in Macrophages. Immunity. 2010;32:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Laslo P, Spooner CJ, Warmflash A, Lancki DW, Lee H-J, Sciammas R, et al. Multilineage Transcriptional Priming and Determination of Alternate Hematopoietic Cell Fates. Cell. 2006;126:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hock H, Hamblen MJ, Rooke HM, Traver D, Bronson RT, Cameron S, et al. Intrinsic Requirement for Zinc Finger Transcription Factor Gfi-1 in Neutrophil Differentiation. Immunity. 2003;18:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cameron ER, Neil JC. The Runx genes: lineage-specific oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Oncogene. 2004;23:4308–4314. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang D-E, Zhang P, Wang N-d, Hetherington CJ, Darlington GJ, Tenen DG. Absence of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor signaling and neutrophil development in CCAAT enhancer binding protein-a deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:569–574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Radomska HS, Huettner CS, Zhang P, Cheng T, Scadden DT, Tenen DG. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein alpha Is a Regulatory Switch Sufficient for Induction of Granulocytic Development from Bipotential Myeloid Progenitors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4301–4314. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhang DE, Hohaus S, Voso MT, Chen HM, Smith LT, Hetherington CJ, et al. Function of PU.1 (Spi-1), C/EBP, and AML1 in early myelopoiesis: Regulation of multiple myeloid CSF receptor promoters. Molecular Aspects of Myeloid Stem Cell Development. 1996;211:137–147. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85232-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annual Review of Immunology. 2006;24:705–738. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gombart AF, Koeffler HP. Neutrophil specific granule deficiency and mutations in the gene encoding transcription factor C/EBP epsilon. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2002;9:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jones LC, Lin ML, Chen SS, Krug U, Hofmann WK, Lee S, et al. Expression of C/EBP beta from the C/ebp alpha gene locus is sufficient for normal hematopoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2002;99:2032–2036. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, Graf T. Stepwise Reprogramming of B Cells into Macrophages. Cell. 2004;117:663–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bussmann LH, Schubert A, Vu Manh TP, De Andres L, Desbordes SC, Parra M, et al. A Robust and Highly Efficient Immune Cell Reprogramming System. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:554–566. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Treiber T, Mandel EM, Pott S, Györy I, Firner S, Liu ET, et al. Early B Cell Factor 1 Regulates B Cell Gene Networks by Activation, Repression, and Transcription- Independent Poising of Chromatin. Immunity. 2010;32:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Decker T, Pasca di Magliano M, McManus S, Sun Q, Bonifer C, Tagoh H, et al. Stepwise Activation of Enhancer and Promoter Regions of the B Cell Commitment Gene Pax5 in Early Lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2009;30:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Jhunjhunwala S, van Zelm MC, Peak MM, Cutchin S, Riblet R, van Dongen JJM, et al. The 3D Structure of the Immunoglobulin Heavy-Chain Locus: Implications for Long-Range Genomic Interactions. Cell. 2008;133:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Degner SC, Wong TP, Jankevicius G, Feeney AJ. Cutting Edge: Developmental Stage-Specific Recruitment of Cohesin to CTCF Sites throughout Immunoglobulin Loci during B Lymphocyte Development. J Immunol. 2009;182:44–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Reya T, O'Riordan M, Okamura R, Devaney E, Willert K, Nusse R, et al. Wnt Signaling Regulates B Lymphocyte Proliferation through a LEF-1 Dependent Mechanism. Immunity. 2000;13:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]