Abstract

Cadmium (Cd), a toxic environmental contaminant, induces neurodegenerative diseases. Recently we have shown that Cd elevates intracellular free calcium ion ([Ca2+]i) level, leading to neuronal apoptosis partly by activating mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. However, the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated. Here we show that the effects of Cd elevated [Ca2+]i on MAPK and mTOR network as well as neuronal cell death are through stimulating phosphorylation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). This is supported by the findings that chelating intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA/AM or preventing Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation using 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) blocked Cd activation of CaMKII. Inhibiting CaMKII with KN93 or silencing CaMKII attenuated Cd activation of MAPK/mTOR pathways and cell death. Furthermore, inhibitors of mTOR (rapamycin), JNK (SP600125) and Erk1/2 (U0126), but not of p38 (PD169316), prevented Cd-induced neuronal cell death in part through inhibition of [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylation. The results indicate that Cd activates MAPK/mTOR network triggering neuronal cell death, by stimulating CaMKII. Our findings underscore a central role of CaMKII in the neurotoxicology of Cd, and suggest that manipulation of intracellular Ca2+ level or CaMKII activity may be exploited for prevention of Cd-induced neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: cadmium, apoptosis, calcium ion, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, mitogen-activated protein kinase, mammalian target of rapamycin

Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) pollution in the environment may be accumulated in human organs through direct exposure or food chain, resulting in many diseases such as pulmonary edema, respiratory tract irritation, renal dysfunction, anemia, osteoporosis, and cancer in humans (Satarug et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008a). Cd also severely affects the function of the nervous system (Lopez et al., 2003), with symptoms including headache and vertigo, olfactory dysfunction, parkinsonian-like symptoms, slowing of visuomotor functioning, peripheral neuropathy, decreased equilibrium, decreased ability to concentrate, and learning disabilities (Pihl and Parkes, 1977; Kim et al., 2005; Monroe and Halvorsen, 2006). A growing number of clinical investigations have pointed to Cd intoxication as a possible etiological factor of neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease (Okuda et al., 1997; Johnson, 2001; Panayi et al., 2002). However, the exact mechanism(s) through which Cd elicits its neurotoxic effects is still unresolved.

Multiple studies have shown that the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling pathways, which comprise a highly conserved cascade of serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinases connecting cell surface receptors to regulatory targets in response to various stimuli, play a critical role in neuronal apoptosis (Kyriakis and Avruch, 2001; Pearson et al., 2001; Li et al., 2004). There exist at least three distinct groups of MAPKs, including extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK, in mammalian cells. Erk1/2 can be activated by growth factors, and is involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation and development, whereas JNK and p38 signaling cascades can be activated by environmental stress and inflammatory cytokines, and have been shown to promote neuronal cell death (Rockwell et al., 2004). Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a Ser/Thr kinase, lies downstream of protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) (Kim et al., 2000; Huang and Houghton, 2003), and senses mitogenic stimuli, nutrient conditions (Fang et al., 2001; Hara et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2002) and ATP (Dennis et al., 2001), regulating cell proliferation, growth and survival (Bjornsti and Houghton, 2004). Akt may positively regulate mTOR, leading to increased phosphorylation of ribosomal p70 S6 kinase (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), the two best characterized downstream effector molecules of mTOR (Bjornsti and Houghton, 2004). We have demonstrated that all three MAPK members can be activated by Cd in neuronal (PC12 and SH-SY5Y) cells, and identified that Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis is partially associated with activation of JNK, Erk1/2, but not by p38 signaling (Chen et al. 2008b). Especially, we have pinpointed that Cd induces apoptosis of neuronal cells in part by activation of Akt/mTOR signaling pathway (Chen et al., 2008b). However, it is still not well understood how Cd activates MAPKs and mTOR signaling pathways in the neuronal cells.

Other studies has implicated that Cd-induced cell apoptosis involves a sustained elevation of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) (Shen et al., 2001; Li et al., 2003; Lemarie et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2007; Biagioli et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Prolonged change in calcium distribution in cells triggers various cascades that lead to apoptosis (Hajnoczky et al., 2003). Recently we have shown that Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation activates MAPK and mTOR pathways, thereby leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells (Xu et al., 2011). However, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a Ser/Thr specific protein kinase, is a general integrator of Ca2+ signaling (Colbran and Brown, 2004; Liu and Templeton, 2007). CaMKII is activated in the presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin (CaM), which leads to autophosphorylation, generating a Ca2+/CaM-independent form of the enzyme (Schworer et al., 1986). In addition, CaMKII transduces signals to MAPKs involved in cell proliferation or apoptosis (Wright et al., 1997; Yamanaka et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008a; Kim et al., 2008b; Lin et al., 2008; Liu and Templeton, 2008; Olofsson et al., 2008). This prompted us to study whether Cd activates MAPK and mTOR pathways triggering neuronal apoptosis, through CaMKII activation by elevated [Ca2+]i.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Cadmium chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in sterile distilled water to prepare the stock solutions (0–120 μM), filtered through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane, aliquoted, and stored at room temperature. Rapamycin (ALEXIS, San Diego, CA, USA) was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 100 μg/ml stock solution and was stored at −20°C. Fluo-3/AM was from Fluka (Buchs, SG, Switzerland). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, NEUROBASAL™ Media, and B27 Supplement were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA), whereas horse serum and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were supplied by Minhai Corp. (Lanzhou, China). Enhanced chemiluminescence solution was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetra(acetoxymethyl) ester (BAPTA/AM) and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borane (2-APB) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). KN93 was from ALEXIS, whereas SP600125, U0126, and PD169316 were form Sigma. The following antibodies were used: CaMKII, phospho-CaMKII (Thr286), phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-S6K1 (Thr389), phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr70), 4E-BP1 (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), Akt, S6K1, Erk2, JNK1, phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun (Ser63), p38 (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), b-tubulin (Sigma), goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, and rabbit anti-goat IgG-HRP (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Poly-D-lysine (PDL) and 4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma. Other chemicals were purchased from local commercial sources and were of analytical grade quality.

Cell culture

Rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell line was from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). PC12 cells were used for no more than ten passages, and cultured in antibiotic-free DMEM supplemented with 10% horse serum and 5% FBS. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Primary cortical neurons were obtained from fetal mice at 16–18 days of gestation and cultured as described (Chen et al., 2010).

Lentiviral shRNA cloning, production, and infection

To generate lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII, oligonucleotides containing the target sequences were synthesized, annealed and inserted into FSIPPW lentiviral vector via the EcoR1/BamH1 restriction enzyme site, as described previously (Liu et al., 2008). Oligonucleiotides used were: sense: 5′-AATTCCCCTGATTGAAGCCATCAACATGCAAGAGATGTTGATGGCTTCAATC AGTTTTTG-3′, anti-sense: 5′-GATCCAAAAACTGATTGAAGCCATCAACATCTCT TGCATGTTGATGGCTTCAATCAGGGG-3′. Lentiviral shRNA targeting GFP (control) was described (Liu et al., 2008). To produce lentivirus with CaMKII shRNA, above constructs were transfected to 293TD cells, then the lentivirus-containing supernatant was used to infect targeting cells following the procedure described (Chen et al., 2011).

Cell viability assay and morphological analysis

Primary neurons, PC12 cells, or PC12 cells infected with lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII or GFP (control), respectively, were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/well in a flat-bottomed 96-well plate, pre-coated with PDL (0.2 μg/ml). Next day, cells were treated with 0–120 μM Cd for 24 h, with 20 μM Cd for 0–24 h, or with/without 10 and 20 μM Cd for indicated time following pre-incubation with/without 100 μM 2-APB or 10 μM KN93 for 1 h with five replicates of each treatment. Subsequently, each well was added 0.01 ml (5 mg/ml) of MTT reagent and incubated for 4 h. After the incubation, the incubation precipitates were dissolved with 0.1 ml of SDS. Cell viability was determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at 570 nm using an ELx800 Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, Vermont, USA). In addition, the cells were also seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in a PDL-coated six-well plate. Next day, cells were exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) following pre-incubation with/without 20 μM BAPTA/AM, 2-APB, or KN93 for 1 h. After incubation for 24 h, the images were taken with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon, Japan) (200×) equipped with a digital camera.

Flow cytometry for [Ca2+]i staining

PC12 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes, pre-coated with PDL, at a density of 1 × 106 cells/dish in the complete growth medium. Next day, cells were exposed to Cd (0–20 μM) for 4 h and 24 h with triplicate of each treatment, followed by harvesting cells, washing 3 times with PBS. Subsequently, cell suspensions (100 μl) for [Ca2+]i staining were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-3/AM for 30 min at 37°C in the dark, and then washed once with PBS to remove the extracellular Fluo-3/AM. Fluo-3/AM was replaced by PBS as a negative control. All samples were analyzed to detect the status of [Ca2+]i under a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Vantage SE flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, California, USA) using the CellQuest software.

Analysis for [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity

PC12 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in the complete growth medium in a PDL-coated six-well plate. Next day, cells were treated with/without Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 4 h and 24 h following pre-incubation with/without rapamycin (Rap, 0.2 μg/ml) for 48 h, or with/without SP600125 (20 μM), U0126 (5 μM), PD169316 (20 μM), BAPTA/AM (20 μM), or 2-APB (100 μM) for 1 h, followed by harvesting cells and washing with PBS. Subsequently, cell suspensions (100 μl) for [Ca2+]i analysis were loaded with Fluo-3/AM as described above. Afterwards, [Ca2+]i fluorescent intensity was detected as described (Chen et al., 2011).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described (Chen et al., 2011).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard error (mean ± S.E.). Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t-test (STATISTICA, Statsoft Inc, Tulsa, OK). A level of P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

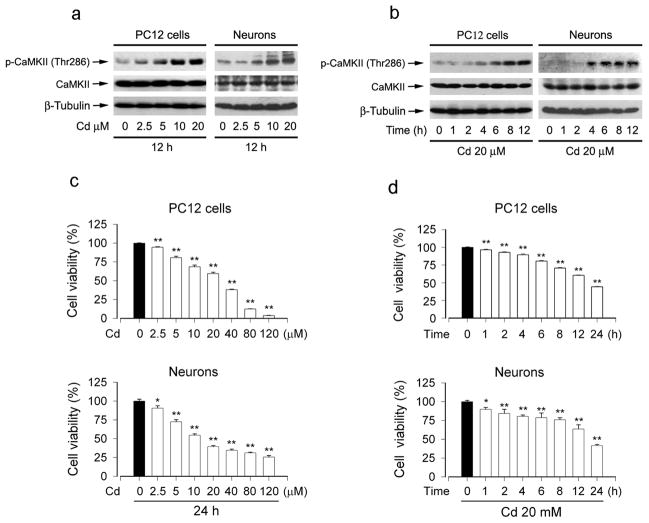

Cd induced CaMKII phosphorylation in neuronal cells

Activation of CaMKII is pro-apoptotic or anti-apoptotic depending on cell types or experimental conditions (Wright et al., 1997; Fladmark et al., 2002; Liu and Templeton, 2007; Rokhlin et al., 2007; Vila-Petroff et al., 2007). To determine the role of CaMKII activity in Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis, PC12 cells and primary neurons, respectively, were exposed to 0–20 μM Cd for 12 h, or to 20 μM Cd for different time (0–12 h). We found that exposure of neuronal cells to Cd resulted in phospho-CaMKII increase in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1a and b), and a dramatically increased phosphorylation of CaMKII was seen at 12 h of exposure to 10 and 20 μM Cd (Fig. 1a) and at 8–12 h post exposure to 20 μM Cd (Fig. 1b), respectively. Furthermore, Cd-elevated phospho-CaMKII level was consistent with decreased cell viability (Fig. 1c and d) or increased apoptosis in PC12 cells and/or primary neurons (Chen et al., 2008b), suggesting that Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis might be associated with its induction of CaMKII phosphorylation

Fig. 1.

Cd induced CaMKII phosphorylation in neuronal cells. (a) PC12 cells or primary neurons were treated with 0–20 μM Cd for 12 h, or (b) with 20 μM Cd for 0–12 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Cd induced phosphorylation of CaMKII in a concentration-dependent (a) and time-dependent (b) manner. (c and d) Cell viability of PC12 cells or primary neurons treated with different concentration of Cd for 24 h (c), or treated with 20 μM Cd for various time (d) was evaluated using MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=4–6. **P<0.01 difference with control group.

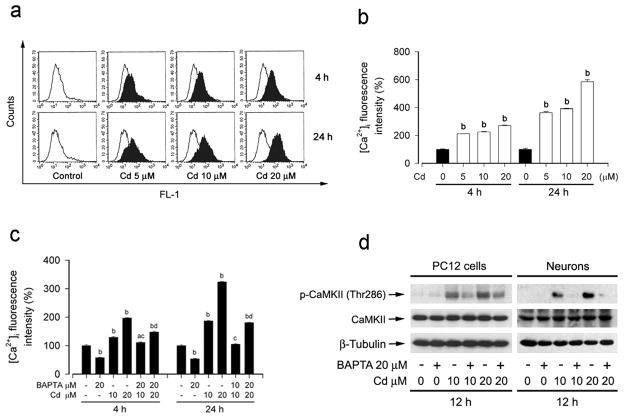

Cd-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII was attributed to [Ca2+]i elevation in neuronal cells

CaMKII is a general integrator of Ca2+ signaling (Liu and Templeton, 2007), which is activated in the presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin, resulting in autophosphorylation and generation of a Ca2+/CaM-independent form of the enzyme (Schworer et al., 1986). Our recent studies have demonstrated that Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with its induction of [Ca2+]i elevation, and unveiled that Cd-elevated [Ca2+]i activates MAPK/mTOR pathways and apoptosis in neuronal cells through calcium-binding protein CaM (Xu et al., 2011). Therefore, we proposed that Cd induction of [Ca2+]i elevation may activate MAPK/mTOR pathways and neuronal apoptosis by induction of CaMKII phosphorylation. To test the hypothesis, first of all, we examined whether Cd-elevated [Ca2+]i really activates CaMKII in neuronal cells. Consistent with our previous findings (Xu et al., 2011), treatment with Cd for 4 h and 24 h resulted in a concentration-dependent increase of [Ca2+]i at concentrations of 0–20 μM in PC12 cells (Fig. 2a and b). Pre-treatment for 1 h with 20 μM BAPTA/AM, an intracellular Ca2+ chelator, significantly attenuated [Ca2+]i elevation induced by Cd (10 and 20 μM) exposure for 4 h and 24 h in PC12 cells (Fig. 2c) or primary neurons (data not shown). Interestingly, chelating intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA/AM obviously inhibited Cd-induced CaMKII phosphorylation in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Cd induced CaMKII phosphorylation via induction of [Ca2+]i elevation. (a) Represent data show increasing [Ca2+]i fluorescent intensity (shift to right) at 4 and 24 h post treatment of PC12 cells with Cd (0–20 μM) using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), with a fluorescent probe, Fluo-3/AM. (b) Quantitative analysis of FACS assay (a) shows changes of [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity in Cd-treated PC12 cells. (c) PC12 was pretreated with/without 20μM BAPTA/AM for 1 h, and then exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 4 h and 24 h. [Ca2+]i fluorescent intensity was assayed by Fluo-3/AM using a microplate reader, showing that BAPTA/AM strongly suppressed Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation in the cells. (d) PC12 cells or primary neurons treated with/without Cd (10 and 20μM) for 12 h post pretreatment with BAPTA/AM for 1 h were harvested. The cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=3–5. bP<0.01, difference with control group; cP<0.01, difference with 10 μM Cd group; dP<0.01, difference with 20 μM Cd group.

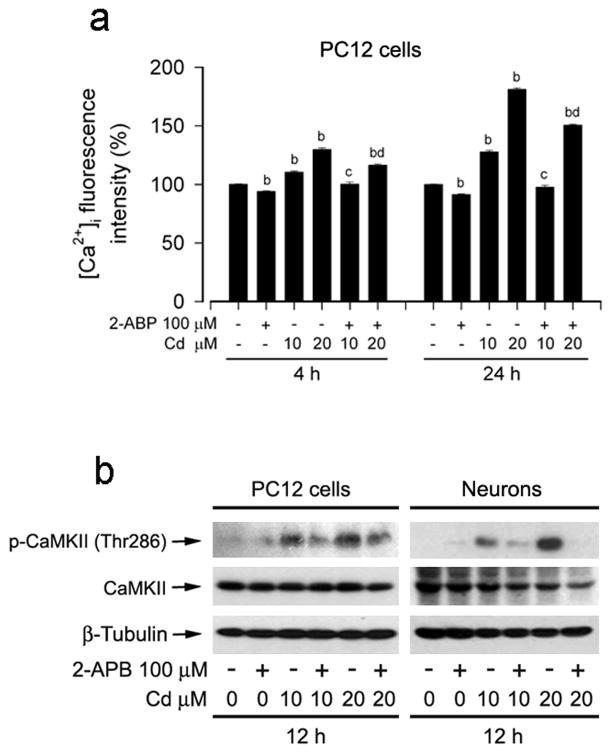

2-APB, at concentrations of ≥50 μM, functions not only as a membrane-permeable inhibitor of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors on endoplasmic reticulum (ER), but also as an inhibitor of extracellular Ca2+ influx through the Ca2+ release activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels on plasma membrane (Prakriya and Lewis, 2001; Bilmen et al., 2002; Braun et al., 2003). Next, 2-APB was employed to prevent Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. As expected, pretreatment with 2-APB (100 μM) markedly attenuated Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation (Fig. 3a). Like BAPTA/AM, 2-APB also partially blocked Cd activation of CaMKII in PC12 cells or primary neurons (Fig. 3b). Taken together, the results indicate Cd induction of [Ca2+]i elevation stimulates CaMKII phosphoryaltion.

Fig. 3.

Prevention of [Ca2+]i elevation by 2-APB attenuated Cd-induced CaMKII phosphorylation. PC12 cells or primary neurons were pretreated with/without 2-APB (100 μM) for 1 h, and then exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for indicated time. (a) [Ca2+]i fluorescent intensity was assayed by Fluo-3/AM using a microplate reader, showing that 2-APB markedly attenuated Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation in the cells. (b) Cd induction of CaMKII phosphorylation was inhibited by 2-APB, as detected by Western blotting using indicated antibodies. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=5. bP<0.01, difference with control group; cP<0.01, difference with 10 μM Cd group; dP<0.01, difference with 20 μM Cd group.

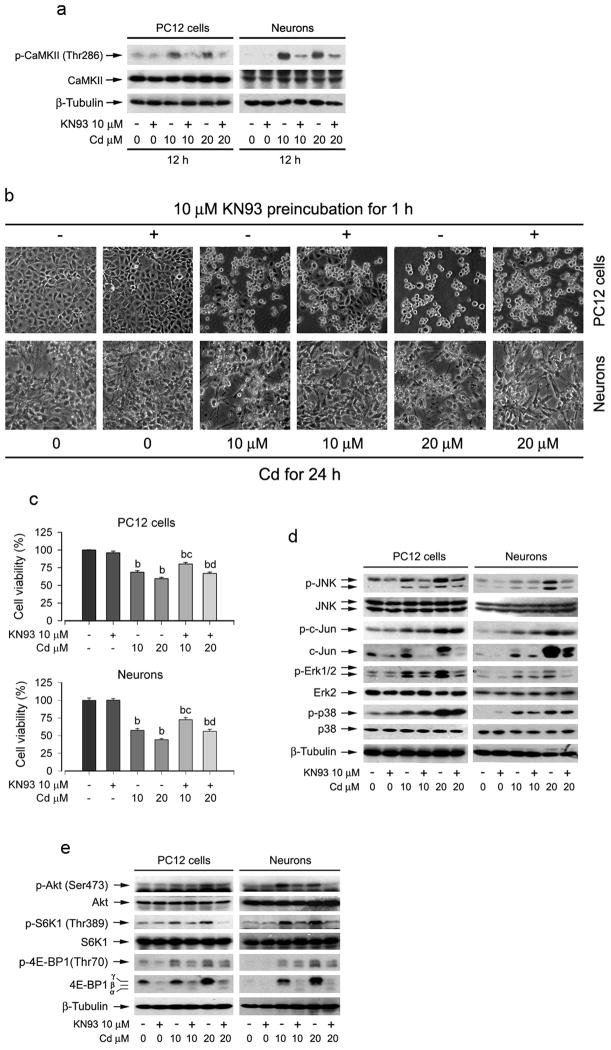

Cd elicited CaMKII phosphorylation leading to activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways and neuronal apoptosis

To unravel whether Cd induction of CaMKII phosphorylation is correlated with its activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways as well as apoptosis in neuronal cells, PC12 cells were exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 12 h after pretreatment with CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h. We found that Cd-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII was obviously attenuated by KN93 in PC12 cells or primary neurons (Fig. 4a). Morphological analysis (Fig. 4b) revealed that KN93 itself did not alter cell shape. Cd alone (10 and 20 μM) induced cell roundup and shrinkage. However, KN93 partially prevented Cd-induced morphological change. Results from the MTT assay (Fig. 4c) further demonstrated that KN93 significantly suppressed Cd-induced loss of cell viability in PC12 cells and primary neurons. Of importance, KN93 partially blocked Cd-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Fig. 4d). Cd-activated phosphorylation of Akt, S6K and 4E-BP1 in PC12 cells and primary neurons were also markedly reduced by KN93 (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of CaMKII by KN93 attenuated Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways as well as neuronal cell death. PC12 cells and/or primary neurons were pretreated with/without KN93 (10 μM) for 1 h, and then exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for indicated time. (a) KN93 obviously blocked Cd-induced CaMKII phosphorylation in PC12 cells and primary neurons. (b) Morphology of PC12 cells was visualized under a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted phase-contrast microscope (200×) equipped with digital camera. KN93 partially rescued cells from Cd-induced apoptosis. (c) Cell viability for PC12 cells and primary neurons was evaluated by MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=5. bP<0.01, difference with control group; cP<0.01, difference with 10 μM Cd group; dP<0.01, difference with 20 μM Cd group. (d and e) Cd-induced phosphorylation of JNK, Erk1/2, and p38, as well as Akt and mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 was inhibited in part by KN93 in PC12 cells and primary neurons. The cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments.

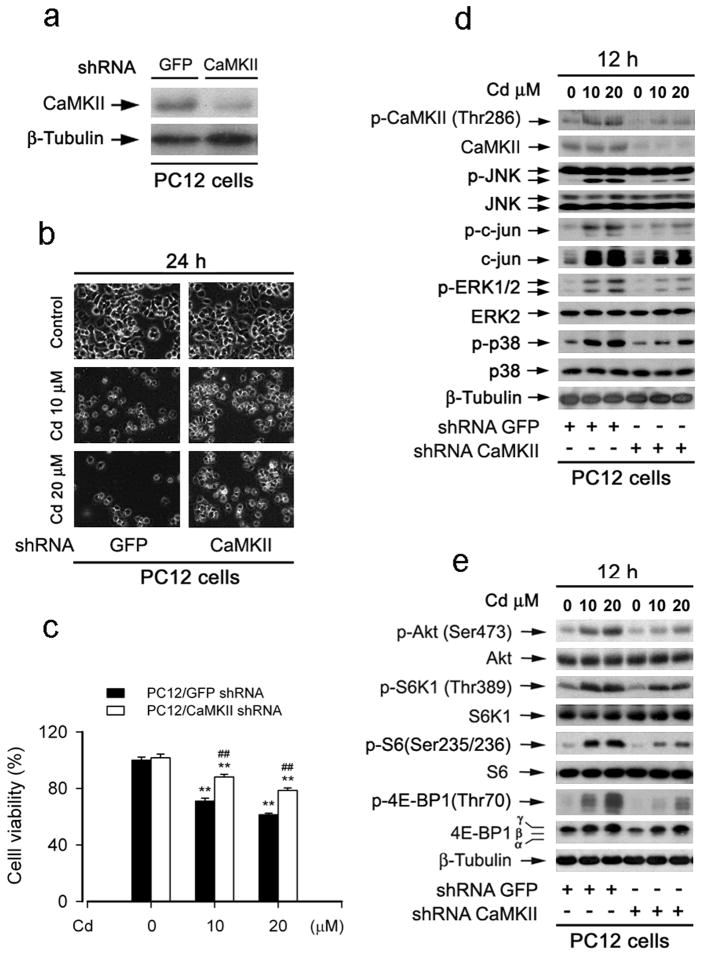

To further substantiate the role of CaMKII in Cd activation of MAPK/mTOR pathways and neuronal cell death, expression of CaMKIIα was silenced by RNA interference. As shown in Fig. 5a, lentiviral shRNA to CaMKIIα, but not to GFP, downregulated CaMKII expression by ~90% in PC12 cells. Downregulation of CaMKII in part prevented Cd-induced cell death in PC12 cells (Fig. 5b and c). Furthermore, silencing CaMKII obviously attenuated Cd-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII (Fig. 5d). Consistently, downregulation of CaMKII conferred partial resistance to Cd activation of MAPKs and mTOR signaling pathways (Fig. 5d and e). The results indicate that Cd activates MAPK/mTOR signaling pathways and neuronal apoptosis by inducing CaMKII phosphorylation.

Fig. 5.

Downregulation of CaMKII prevented Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways as well as neuronal cell death. (a) Downregulation of CaMKII (by ~ 90%) by lentiviral shRNA to CaMKII and GFP (as control) in PC12 cells, as detected by Western blotting with antibodies to CaMKII. (b) Morphology of lentiviral shRNA-infected cells, treated with/without Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 24 h, was visualized under a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted phase-contrast microscope (200×) equipped with digital camera. (c) Cell viability was evaluated using MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=8. **P<0.01, difference with control group; ##P<0.01, CaMKII shRNA group vs GFP shRNA group. (d and e) lentiviral shRNA-infected cells were exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 12 h, followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies, showing that downregulation of CaMKII conferred partial resistance to Cd activation of MAPKs and mTOR signaling pathways. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments.

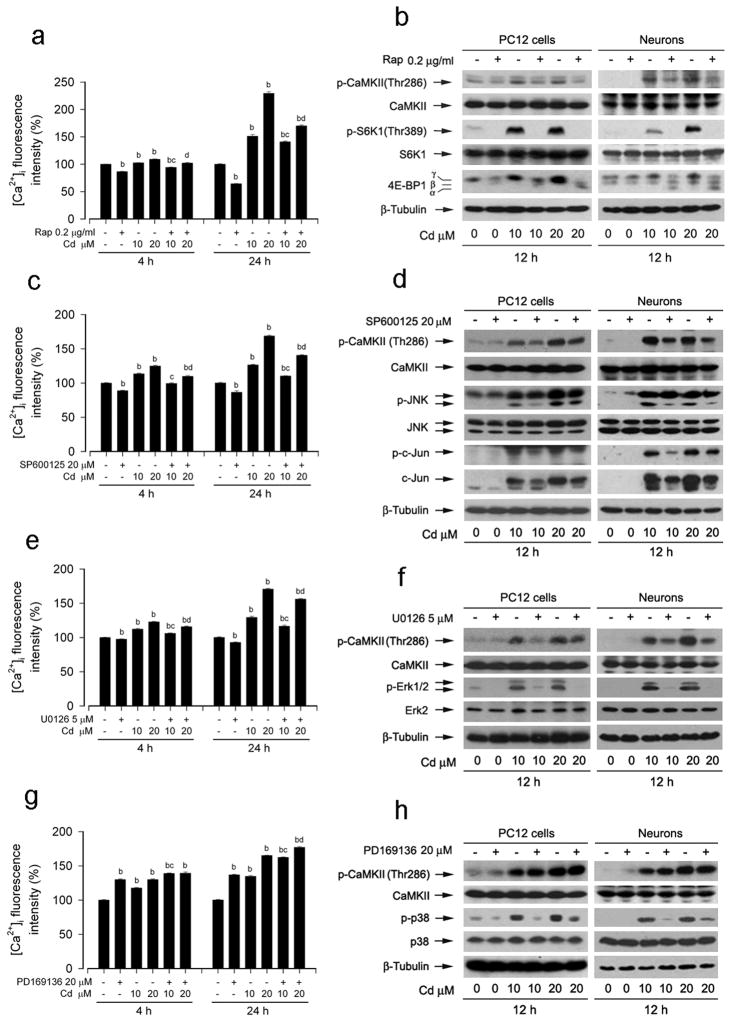

Inhibitors of mTOR, JNK and Erk1/2, but not p38, partially inhibited Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylation, preventing neuronal cell death

Recently we have demonstrated that rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR (Huang and Houghton, 2003), may exert a beneficial effect against Cd-induced neuronal cell death by blocking mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Chen et al., 2008b). We have also shown that inhibitors of JNK and Erk1/2 partially prevent Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting phosphorylation of JNK and Erk1/2, respectively (Chen et al., 2008b). Cd induced [Ca2+]i elevation activates MAPKs and mTOR network (Xu et al., 2011). To investigate whether MAPKs and mTOR pathways reversely regulate Cd-induced intracellular Ca2+ elevation and CaMKII phosphorylation, PC12 cells and/or primary neurons were exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for 4 h and 24 h, or 12 h after pretreatment with rapamycin, JNK inhibitor SP600125, MEK1/2 (upstream of Erk1/2) inhibitor U0126, or p38 inhibitor PD169316 for indicated time, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6a, pretreatment with rapamycin obviously reduced Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation in PC12 cells. Consistently, we found that rapamycin dramatically blocked activation of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 with a concomitant reduction of CaMKII phosphorylaiton in Cd-exposed PC12 cells and primary neurons (Fig. 6b). Similar effects of 20 μM SP600125 (Fig. 6c and d) and 5 μM U0126 (Fig. 6e and f), but not 20 μM PD169316 (Fig. 6g and h), on Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII activation were seen in PC12 cells and/or primary neurons. The findings suggest that inhibitors of mTOR, JNK and Erk1/2 may prevent Cd-induced neuronal cell death in part through inhibition of [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

Inhibitors of mTOR, JNK and Erk1/2, but not of p38, partially inhibited Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylation, preventing neuronal apoptosis. PC12 cells or primary neurons were exposed to Cd (10 and 20 μM) for indicated time after pretreatment with 0.2 mg/ml mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (Rap) for 48 h or with 20 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125, 5 μM MEK1/2 (upstream of Erk1/2) inhibitor U0126, or 20 μM p38 inhibitor PD169316 for 30 min, respectively. (a) Rap obviously reduced Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. (b) Rap blocked activation of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 with a concomitant reduction of CaMKII phosphorylaiton in Cd-exposed PC12 cells. SP600125 (c and d) and U0126 (e and f), but not PD169316 (g and h), partially prevented Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylaiton. [Ca2+]i fluorescent intensity was evaluated by a fluorescent probe, Fluo-3/AM, using a microplate reader. Western blot analysis was performed using indicated antibodies. The blots were probed for β-tubulin as a loading control. Similar results were observed in at least three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SE; n=5. bP<0.01, difference with control group; cP<0.01, difference with 10 μM Cd group; dP<0.01, difference with 20 μM Cd group.

Discussion

Calcium ion (Ca2+), as a second messenger, mediates a variety of physiological responses of neurons to neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors (Cheng et al., 2003). However, deregulated cellular Ca2+ homeostasis contributes to neuronal cell death, which is implicated in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (Gibbons et al., 1993; Kawahara and Kuroda, 2000; Mattson, 2007; Marambaud et al., 2009). Cd, a highly toxic heavy metal, occurs frequently in the polluted environment and has a long biological half-life (15–20 years) in humans (Jin et al., 1998). Its targets of toxicity including liver, lung, kidney, testis, bone, etc., resulting in many diseases such as pulmonary edema, respiratory tract irritation, renal dysfunction, anemia, osteoporosis, and cancer in humans (Satarug et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008a). Cd also severely affects the function of the nervous system by its induction of neuronal apoptosis, and thereby contributes to neurodegenerative diseases (Lopez et al., 2003). We previously have demonstrated that Cd induces apoptosis of neuronal (PC12 and SH-SY5Y) cells via activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling network (Chen et al., 2008b). Recently our further studies revealed that Cd elevated [Ca2+]i level, leading to neuronal apoptosis in part through activation of MAPKs and mTOR pathways (Xu et al., 2011). Here, we provide evidence that the effects of Cd-elevated [Ca2+]i on MAPKs and mTOR network as well as neuronal cell death are through stimulating phosphorylation of CaMKII. The data indicate that CaMKII, as a key signaling protein, plays a bridging role between Cd induction of [Ca2+]i elevation and activation of MAPK and mTOR network, leading to neuronal cell death.

CaMKII, a multifunctional Ser/Thr kinase ubiquitously expressed in all neuronal compartments, is prominent among the Ca2+-sensitive processes (Colbran and Brown, 2004). It is activated upon binding of Ca2+-containing CaM, which undergoes autophosphorylation, and then takes on autonomous activity independent of calmodulin binding (Hudmon and Schulman, 2002). Based on the unique regulatory properties of CaMKII and our recent findings that Cd induces [Ca2+]i elevation with a concomitant increase of CaM function contributing to neuronal apoptosis, we speculated that CaMKII is an ‘interpreter’ of Cd induction of Ca2+ signaling, leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. In the present study, we observed that exposure of neuronal cells (PC12 cells and primary neurons) to Cd resulted in phospho-CaMKII increase in a time- and concentration-dependent manner, which was consistent with decreased cell viability (Fig. 1c and d) or increased apoptosis of PC12 cells (Chen et al., 2008b). Chelation of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA/AM blocked Cd activation of CaMKII. We have recently noticed that BAPTA/AM attenuated Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways as well as cell death in PC12 cells or primary neurons (Xu et al., 2011). These findings suggest that Cd-elevated [Ca2+]i activates CaMKII, which might be associated with activation of MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways, leading to neuronal apoptosis.

Many cell death stimuli are known to alter the concentration of Ca2+ in the cytosol and the storage of Ca2+ in the intracellular organelles (Baffy et al., 1993; Bian et al., 1997). [Ca2+]i increase is usually attribute to Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores and/or Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space (Jan et al., 2001). The ER is one of the major calcium storage units in cells, and blockers of the ER calcium channel, such as IP3 receptors, can effectively prevent Ca2+ release induced by various stimuli including Cd (Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular environment, following internal Ca2+ store depletion, provides the elevated and sustained [Ca2+]i levels, which is associated with the activation of the CRAC channels on the plasma membrane (Prakriya and Lewis, 2001; Lewis et al., 2008). Studies have demonstrated that 2-APB (≥50 μM) inhibits both IP3 receptors and CRAC channels, blocking ER Ca2+ release and extracellular Ca2+ influx (Prakriya and Lewis, 2001; Bilmen et al., 2002; Braun et al., 2003). Therefore, 2-APB (100 μM) was employed to prevent Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. As expected, 2-APB did block Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. Importantly, like BAPTA/AM, 2-APB remarkably attenuated Cd-induced phosphorylation of CaMKII. Furthermore, we found that Cd-activated MAPK/mTOR pathways were partially inhibited by 2-APB as well (data not shown). This is in line with our recent findings that pretreatment with ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (EGTA), an extracellular Ca2+ chelator, which renders the inaccessibility of extracellular Ca2+ to the cells, dramatically prevented Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways, as well as cell death (Xu et al., 2011). Taken together, our results suggest that Cd may induce ER Ca2+ release via activation of IP3 receptors on the ER and extracellular Ca2+ influx by activation of CRAC channels on plasma membrane, resulting in [Ca2+]i elevation contributing to CaMKII phosphorylation.

To demonstrate that CaMKII is essential for Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways as well as neuronal cell death, pharmacological inhibition or genetic manipulation of CaMKII activity was utilized. Pretreatment with KN93, a specific inhibitor of CaMKII (Choi et al., 2006), blocked Cd-induced CaMKII phosphorylation, and partially prevented Cd-induced death in PC12 cells and primary neurons (Fig. 4a–c). Consistently, Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways was obviously blocked by KN93 in PC12 cells and primary neurons as well (Fig. 4d and e). Furthermore, downregulation of CaMKII by RNA interference also attenuated Cd activation of MAPK and mTOR pathways as well as neuronal cell death. These findings strongly suggest that Cd activates MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways by CaMKII phosphorylation, leading to neuronal cell death.

Recently we have shown that a selective mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, may dramatically rescue Cd-induced neuronal cell death by blocking mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Chen et al., 2008b). Consistently, in the study, we noted that rapamycin was able to attenuate Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII phosphorylaiton in PC12 cells and/or primary neurons. In addition, we also found that SP600125 (a specific JNK inhibitor) and U0126 (a specific inhibitor of MEK1/2, upstream kinases of Erk1/2), but not PD169136 (a specific p38 inhibitor), could prevent Cd-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII activation in PC12 cells and/or primary neurons. The results are consistent with our previous findings that inhibition of JNK or Erk1/2 by specific inhibitors or RNA interference partially prevented Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis (Chen et al., 2008b). Our data suggest that JNK, Erk1/2 and mTOR are involved in controlling the cellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and their inhibitors prevent neuronal cell death, not only by directly inhibiting the activities of the kinases, but also by inhibiting Cd induction of [Ca2+]i elevation, which, in turn, results in less activation of CaMKII-MAPK/mTOR signaling network.

Four isoforms of p38 (-α, -β, -γ, and -δ) have been identified and especially, various isoforms of p38 have unique cellular functions (Wang et al., 1998; Enslen et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2011). In this study, an antibody to phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) (Cat.# 9215, Cell Signaling) was used, which cannot differentiate isoforms of p38-α, -β, -γ, and -δ. Therefore, currently we do not know what isoforms of p38 MAPK is activated by Cd-activated CaMKII. As activation of p38 MAPK is not involved in Cd-induced neuronal cell death (Chen et al., 2008b), we did not further study what isoforms of p38 was activated.

In summary, we have shown that Cd-elevated [Ca2+]i activates CaMKII in neuronal cells, which elicits MAPK and mTOR network, leading to neuronal cell death. Our findings implicate an important role of CaMKII in Cd neurotoxicology, and suggest that manipulation of intracellular Ca2+ level or CaMKII activity may be exploited for prevention of Cd-induced neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30971486; L. C.), the Scientific Research Foundation of the State Education Ministry of China (SEMR20091341, L. C.), the Project for the Priority Academic Program Development and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (10KJA180027; L. C.), NIH (CA115414; S. H.), American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE; S. H.), and Louisiana Board of Regents (NSF-2009-PFUND-144; S. H.). We thank Dr. Ling Wang for technical assistance in flow cytometry analysis.

Abbreviations

- 2-APB

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- 4E-BP1

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1

- Akt

protein kinase B (PKB)

- BAPTA/AM

1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetra(acetoxymethyl) ester

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular free calcium ion

- Cd

cadmium

- CaMKII

Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CRAC channels

Ca2+ release activated Ca2+ channels

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- Erk1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolim bromide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PDL

poly-D-lysine

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase

- S6K1

S6 kinase 1

- Ser/Thr

serine/threonine

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

References

- Ang ES, Zhang P, Steer JH, Tan JW, Yip K, Zheng MH, Joyce DA, Xu J. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase activity is required for efficient induction of osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:787–795. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffy G, Miyashita T, Williamson JR, Reed JC. Apoptosis induced by withdrawal of interleukin-3 (IL-3) from an IL-3-dependent hematopoietic cell line is associated with repartitioning of intracellular calcium and is blocked by enforced Bcl-2 oncoprotein production. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6511–6519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagioli M, Pifferi S, Ragghianti M, Bucci S, Rizzuto R, Pinton P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and alteration in calcium homeostasis are involved in cadmium-induced apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian X, Hughes FM, Jr, Huang Y, Cidlowski JA, Putney JW., Jr Roles of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and intracellular Ca2+ stores in induction and suppression of apoptosis in S49 cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1241–1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilmen JG, Wootton LL, Godfrey RE, Smart OS, Michelangeli F. Inhibition of SERCA Ca2+ pumps by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB). 2-APB reduces both Ca2+ binding and phosphoryl transfer from ATP, by interfering with the pathway leading to the Ca2+-binding sites. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3678–3687. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: a target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun FJ, Aziz O, Putney JW., Jr 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borane activates a novel calcium-permeable cation channel. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1304–1311. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu L, Huang S. Cadmium activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway via induction of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of protein phosphatases 2A and 5. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008a;45:1035–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu L, Luo Y, Huang S. MAPK and mTOR pathways are involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2008b;105:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Yin J, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR signaling by activation of AMPKalpha leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90:762–773. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Kontos CD, Huang S. Cadmium induction of reactive oxygen species activates the mTOR pathway, leading to neuronal cell death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Wang S, Yang D, Xiao R, Mattson MP. Calmodulin mediates brain-derived neurotrophic factor cell survival signaling upstream of Akt kinase in embryonic neocortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7591–7599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SS, Seo YJ, Shim EJ, Kwon MS, Lee JY, Ham YO, Suh HW. Involvement of phosphorylated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein in the mouse formalin pain model. Brain Res. 2006;1108:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbran RJ, Brown AM. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Mammalian TOR: A Homeostatic ATP Sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enslen H, Brancho DM, Davis RJ. Molecular determinants that mediate selective activation of p38 MAP kinase isoforms. EMBO J. 2000;19:1301–1311. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. Phosphatidic Acid-Mediated Mitogenic Activation of mTOR Signaling. Science. 2001;294:1942–1945. doi: 10.1126/science.1066015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fladmark KE, Brustugun OT, Mellgren G, Krakstad C, Boe R, Vintermyr OK, Schulman H, Doskeland SO. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is required for microcystin-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2804–2811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons SJ, Brorson JR, Bleakman D, Chard PS, Miller RJ. Calcium influx and neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;679:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky G, Davies E, Madesh M. Calcium signaling and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, KY Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;110:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Houghton PJ. Targeting mTOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: the role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:473–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan CR, Cheng JS, Roan CJ, Lee KC, Chen WC, Chou KJ, Tang KY, Wang JL. Effect of diethylstilbestrol (DES) on intracellular Ca2+ levels in renal tubular cells. Steroids. 2001;66:505–510. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Lu J, Nordberg M. Toxicokinetics and biochemistry of cadmium with special emphasis on the role of metallothionein. Neurotoxicology. 1998;19:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. Gradual micronutrient accumulation and depletion in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56:595–597. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara M, Kuroda Y. Molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration induced by Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid protein: channel formation and disruption of calcium homeostasis. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:389–397. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BW, Choi M, Kim YS, Park H, Lee HR, Yun CO, Kim EJ, Choi JS, Kim S, Rhim H, Kaang BK, Son H. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling regulates hippocampal neurons by elevation of intracellular calcium and activation of calcium/calmodulin protein kinase II and mammalian target of rapamycin. Cell Signal. 2008a;20:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Sarbassov D, Ali S, King J, Latek R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini D. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Jung Y, Kim D, Koh H, Chung J. Extracellular zinc activates p70 S6 kinase through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25979–25984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SD, Moon CK, Eun SY, Ryu PD, Jo SA. Identification of ASK1, MKK4, JNK, c-Jun, and caspase-3 as a signaling cascade involved in cadmium-induced neuronal cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SM, Park JG, Baek WK, Suh MH, Lee H, Yoo SK, Jung KH, Suh SI, Jang BC. Cadmium specifically induces MKP-1 expression via the glutathione depletion-mediated p38 MAPK activation in C6 glioma cells. Neurosci Lett. 2008b;440:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signal Transduction Pathways Activated by Stress and Inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, Zhang J, Chiu J. Acquired tolerance in cadmium-adapted lung epithelial cells: roles of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway and basal level of metallothionein. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;215:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarie A, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Morzadec C, Allain N, Fardel O, Vernhet L. Cadmium induces caspase-independent apoptosis in liver Hep3B cells: role for calcium in signaling oxidative stress-related impairment of mitochondria and relocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1517–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TL, Brundage KM, Brundage RA, Barnett JB. 3,4-Dichloropropionanilide (DCPA) inhibits T-cell activation by altering the intracellular calcium concentration following store depletion. Toxicol Sci. 2008;103:97–107. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Xia T, Jiang CS, Li LJ, Fu JL, Zhou ZC. Cadmium directly induced the opening of membrane permeability pore of mitochondria which possibly involved in cadmium-triggered apoptosis. Toxicology. 2003;194:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Arnaud L, Rockwell P, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. A single amino acid substitution in a proteasome subunit triggers aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins in stressed neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2004;90:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Chen PS, Gean PW. Glutamate preconditioning prevents neuronal death induced by combined oxygen-glucose deprivation in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;589:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Chen L, Chung J, Huang S. Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene. 2008;27:4998–5010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Templeton DM. Cadmium activates CaMK-II and initiates CaMK-II-dependent apoptosis in mesangial cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Templeton DM. Initiation of caspase-independent death in mouse mesangial cells by Cd2+: involvement of p38 kinase and CaMK-II. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:307–318. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZM, Chen GG, Vlantis AC, Tse GM, Shum CK, van Hasselt CA. Calcium-mediated activation of PI3K and p53 leads to apoptosis in thyroid carcinoma cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1428–1436. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez E, Figueroa S, Oset-Gasque M, MPG Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced by cadmium in cortical neurons in culture. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:901–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Dreses-Werringloer U, Vingtdeux V. Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe RK, Halvorsen SW. Cadmium blocks receptor-mediated Jak/STAT signaling in neurons by oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda B, Iwamoto Y, Tachibana H, Sugita M. Parkinsonism after acute cadmium poisoning. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99:263–265. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(97)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson MH, Havelka AM, Brnjic S, Shoshan MC, Linder S. Charting calcium-regulated apoptosis pathways using chemical biology: role of calmodulin kinase II. BMC Chem Boil. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6769-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayi AE, Spyrou NM, Iversen BS, White MA, Part P. Determination of cadmium and zinc in Alzheimer’s brain tissue using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu B-e, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-Activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Pathways: Regulation and Physiological Functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Parkes M. Hair element content in learning disabled children. Science. 1977;198:204–206. doi: 10.1126/science.905825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Potentiation and inhibition of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP(3) receptors. J Physiol. 2001;536:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell P, Martinez J, Papa L, Gomes E. Redox regulates COX-2 upregulation and cell death in the neuronal response to cadmium. Cell Signal. 2004;16:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokhlin OW, Taghiyev AF, Bayer KU, Bumcrot D, Koteliansk VE, Glover RA, Cohen MB. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II plays an important role in prostate cancer cell survival. Cancer Boil Ther. 2007;6:732–742. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.5.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satarug S, Baker J, Reilly P, Esumi H, Moore M. Evidence for a synergistic interaction between cadmium and endotoxin toxicity and for nitric oxide and cadmium displacement of metals in the kidney. Nitric Oxide. 2000;4:431–440. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer CM, Colbran RJ, Soderling TR. Reversible generation of a Ca2+-independent form of Ca2+(calmodulin)-dependent protein kinase II by an autophosphorylation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8581–8584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Dong SY, Ong CN. Critical role of calcium overloading in cadmium-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2001;171:12–19. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Petroff M, Salas MA, Said M, Valverde CA, Sapia L, Portiansky E, Hajjar RJ, Kranias EG, Mundina-Weilenmann C, Mattiazzi A. CaMKII inhibition protects against necrosis and apoptosis in irreversible ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SH, Shih YL, Ko WC, Wei YH, Shih CM. Cadmium-induced autophagy and apoptosis are mediated by a calcium signaling pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3640–3652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Chen L, Xia SK. Cadmium is acutely toxic for murine hepatocytes: effects on intracellular free Ca(2+) homeostasis. Physiol Res. 2007;56:193–201. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Huang S, Sah VP, Ross J, Jr, Brown JH, Han J, Chien KR. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogenactivated protein kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2161–2168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SC, Schellenberger U, Ji L, Wang H, Larrick JW. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II mediates signal transduction in apoptosis. FASEB J. 1997;11:843–849. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Chen S, Luo Y, Chen Z, Liu L, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Chen L, Huang S. Calcium signaling is involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis via induction of reactive oxygen species and activation of MAPK/mTOR network. PloS ONE. 2011;6:e19052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Hiragami Y, Maeda N, Toku S, Kawahara M, Naito Y, Yamamoto H. Involvement of CaM kinase II in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced activation of MAP kinase in cultured hypothalamic neurons. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;466:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Harrison JS, Studzinski GP. Isoforms of p38MAPK gamma and delta contribute to differentiation of human AML cells induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]