Abstract

Very little is known about the impact of age and gender on drug abuse treatment needs. To examine this, we recruited 2,573 opioid-dependent patients entering treatment across the country from 2008 to 2010 aged from 18 to 75 to complete a self-administered survey examining drug use histories and the extent of co-morbid psychiatric and physical disorders. Moderate to very severe pain and psychiatric disorders, including poly-substance abuse, were present in a significant fraction of 18–24 year olds, but their severity grew exponentially as a function of age: 75% of those over 45 had debilitating pain and psychiatric problems. Women had more pain than men and much worse psychiatric issues in all age groups. Our results indicate that a “one size fits all” approach to prevention, intervention and treatment of opioid abuse that ignores the shifting needs of men and women opioid abusers as they age is destined to fail.

Keywords: Opioid abuse, prescription drug abuse, opioid treatment centers, age-related changes in treatment needs, age and gender influences on opioid treatment

1. Introduction

It is clear from many nationally based surveys and other studies that the “recreational” use of opioids for non-therapeutic purposes- i.e. to get high - has shown major increases in the past 15 years or so, particularly in adolescents and young adults (McCabe, Cranford & West, 2008; Skurtveit, Furu, Selmer, Handal & Tverdal, 2010; Rogers & Copley, 2009; Schulden, Thomas & Compton, 2009; Boyles, 2009; Cai, Crane, Poneleit & Paulozzi, 2010; Manchikanti, Fellows, Ailinani & Pampati, 2010). Although there is little systematic data available, it seems certain that only a small fraction of these first-time users will ultimately develop problematic use or abuse of prescription opioids. What distinguishes at risk individuals, from true recreational users who can use drugs occasionally with few negative effects, is not fully understood. However, recent data indicate that those most likely to progress from misuse to abuse have significant levels of pain (often undertreated) and other medical and psychiatric co-morbid conditions, including nicotine and alcohol abuse (McCabe, Cranford & West, 2008; Skurtveit, Furu, Selmer, Handal & Tverdal, 2010; Sullivan, Edlund, Steffick & Unützer, 2005; Sullivan, Edlund, Zhang, Unützer & Wells, 2006; Cicero et al., 2009). Given the extent of pre-existing co-morbidity and the ensuing disabilities inflicted by years of substance abuse, it seems logical to predict that, as they age, elderly substance abusers would be gravely ill. Surprisingly, there have been very few published reports in which this has been examined. This could be related to a number of factors: First, reluctance of elderly patients to participate in research studies, particularly when deeply personal questions are asked (Buckwalter, 2009; Melberg & Humphreys, 2010; Papaleontiou et al., 2010; Tourangeau & Smith, (1996); second, lack of interest by researchers who believe that substance abuse is only a problem of the young; or, third, the inability to recruit elderly substance abusers since they are so few in numbers because of “burnout”, or the severity of their co-morbidity. No matter the reason, it remains clear that studies of abuse in the elderly remain greatly limited.

In an effort to study this “underserved” population, we recruited 2,573 patients entering drug treatment programs around the country ranging in age from 18–75, whose primary drug was a prescription opioid. Each of them completed an anonymous self-administered survey which covered a number of retrospective questions related to their history of use and abuse of opioids, their current drug abuse problems, co-morbid physical and psychiatric issues and general physical/mental health.

2. Methods and Methods

2.1 Survey of Key Informants’ Patients (SKIP)

The term “Key Informants” has been used for decades in sociological research and, in terms of our research, is defined as individuals who are well aware of drug abuse issues and patterns in their catchment area; they include researchers, ethnographers and treatment specialists. In the current studies all of the key informants were treatment center directors or their designees, who had daily contact with large numbers of patients who met DSM-IV criteria for abuse/dependence on opioids. This on-going nation-wide survey, termed the Survey of Key Informants’ Patients (SKIP), is a key element of the post-marketing surveillance system: The Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS®) System (Cicero et al., 2007; Dart, 2009). Briefly, SKIP consists of over 100, mostly privately funded, treatment centers, balanced geographically (Cicero, Inciardi & Muñoz, 2005; Cicero, Surratt & Inciardi, 2007; Cicero et al., 2007) with a good representation of large urban, suburban and rural treatment centers. Each of the treatment centers was asked to recruit patients/clients who had a diagnosis of opioid analgesic abuse or dependence using DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria and were just entering treatment.

2.2 Subject Recruitment

Inclusion criteria for this study were very broad: first, subjects had to be 18 years or older (IRB requirement); second, they had to meet DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse whose primary drug was a prescription opioid (i.e., not heroin); and, third, they used prescription opioid drugs to get high at least once in the past 30 days prior to treatment. Overall, 85% of the patients approached by the treatment counselors completed and submitted surveys. The patients were asked to complete a detailed, self-administered survey instrument, covering: demographics; licit and illicit patterns of drug use; diagnostic criteria for alcohol and opioid abuse or dependence using last 30 day use (DSM-IV criteria); the Fagerström test for Nicotine Dependence (Fagerstrom, 1978); general health status using the SF-36v2 Health Survey (Hawthorne, Osborne, Taylor & Sansoni, 2007; Ware, Kosinski & Dewey, 2001); and, whether they were currently being treated for a psychiatric condition.

2.3 SF-36 V2 Health Survey

With the release of SF-36v2, norms were calculated using data from the 1998 National Survey of Functional Health Status (NSFHS) and norm-based scoring (NBS) algorithms were introduced (Hawthorne, Osborne, Taylor & Sansoni, 2007; Ware, Kosinski & Dewey, 2001). Using this model, a T score of 50 (standard deviation = 10) represents the average health status of all adults in this country. A score greater than 50 indicates better than normal health, whereas a score below 50 represents poorer health. To control for the normal age and gender-related differences in physical and mental health (e.g. presumably younger men and women would have T scores greater than 50 – better physical health than the population as a whole), the SF-36V2 also calculates composite population scores for all men and women by age compared to the entire population. Thus, using age and gender appropriate composite scores, the impact of opioid abuse on the general physical and mental health status of men and women entering treatment can easily be assessed.

2.4 Measures

Other than the customary demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, employment status and income), we obtained the composite physical and mental health scores from the well validated SF-36V2, self-reported frequencies of psychiatric disorders which required treatment, pain scored from none to moderate-severe, alcohol and nicotine dependence and the means used to divert opioid medications from the normal medical supply chain.

2.5 Patient/subject confidentiality

Completed survey instruments were identified solely by a unique case number and were sent directly to Washington University School of Medicine. The treatment specialists did not see the detailed responses of their patients/clients.

The protocol was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.6 Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using Predictive Analytics Software (PASW, formerly SPSS) version 18. Bivariate logistic regression models were developed to predict the influence of age and gender on demographics, diversion methods used to obtain prescription opioids, physical and mental health status, alcoholism and nicotine dependence. The significance level was set at p<0.01 for all comparisons.

3. Results

3.1 Demographics

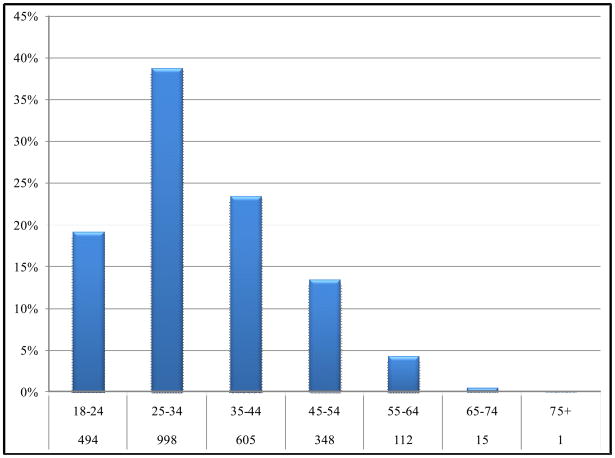

As shown in Figure 1, the frequency distribution of all 2,573 patients by age was an inverted U, bell-shaped curve with the peak at 25–34 years of age. After that, there was a sharp decline such that just 5% of the total population was over the age of 55. Given the low numbers of people over the age of 55 (N=128), in subsequent analyses we pooled data from those 45 or older into a single category (N=476). The sample was predominately white (>80%). There were no gender or age-related differences observed in ethnicity nor were there any ethnic differences observed on any dependent variable. Approximately equal numbers of males and females were present in each age group. The majority were unemployed (>55%), but income levels for those who were employed were comparable to published rates for the general population.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of age of treatment clients.

Percent of the total population (N=2,573) falling into the age brackets shown. The numbers in each age group are shown in italics on the y axis.

3.2 Physical and mental health co-morbidity

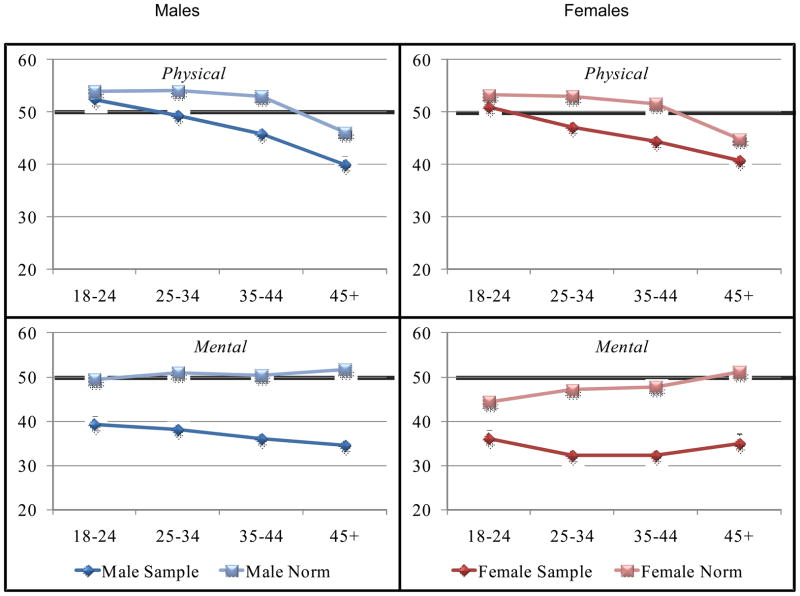

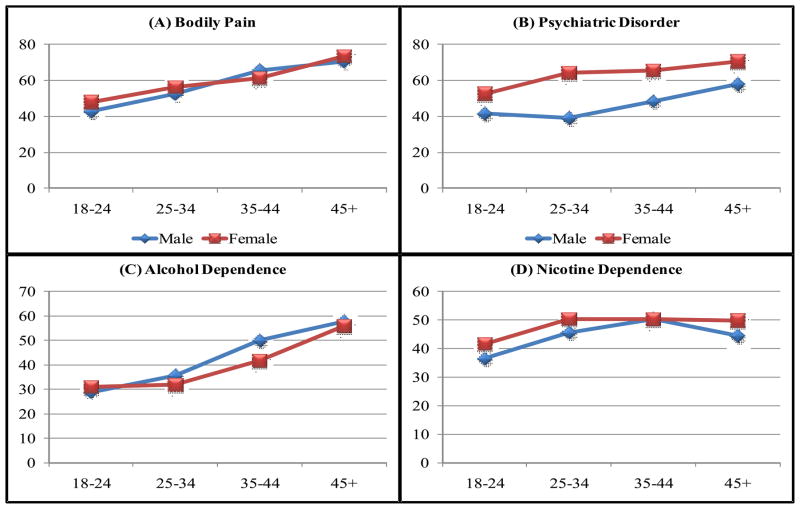

Figure 2 shows the SF-36V2 physical and mental health composite scores (mean, 95% CI) in opioid abusers entering treatment compared to age and gender appropriate population norms. As they aged, both men and women entering treatment had increasingly poorer physical health composite scores than controls. However, the SF-36V2 mental health composite scores, at close to 2 standard deviations from the norm, reflect even worse psychiatric health in aging males and particularly females who misuse opioids. Consistent with the global health analyses provided by the SF-36V2 composite scores, Figure 3 breaks out several aspects of the many physical and mental health problems found in individuals with a primary diagnosis of substance abuse. Table 1 shows the odds ratios for gender and Table 2 shows the OR for age on all dependent variables. Moderate to very severe non-withdrawal bodily pain, which interfered with work and social activities, was a prominent feature in of those in the 18–24 age, but this grew significantly with age such that the odds of those individuals over the age of 45 having moderate to severe pain were 2 times greater than all other age groups (OR=2.12, p<.001). It is also apparent that the incidence of self-reported psychiatric disorders that required treatment was very high relative to published population norms in all ages, but the incidence grew with age: the odds of 45+ old patients having a psychiatric disorder were significantly greater (OR 1.601, p<.001) than younger patients. Overall, the odds of women having psychiatric disorders were much greater than in males (table 1, OR=2.11, p<.001). Figure 3 also shows that there was considerable co-morbid alcoholism and nicotine dependence in the treatment population. Rates of alcoholism were high in the youngest cohort of opioid abusers, but grew significantly with age: males and females over 45 had greater odds of alcoholism than younger patients (OR=2.33, p<.001). Nicotine dependence (i.e. smoking cigarettes) was also pervasive (Figure 3). There were no clear gender differences in either rates of alcoholism or nicotine dependence.

Figure 2. SF36V2 composite physical and mental health scores for both the treatment samples and population norms.

Mean [95% confidence limits] composite physical and mental health scores for males and females on the SF-36V2 health survey. Age adjusted population norms, derived from large population studies carried out in validating the SF-36V2 instrument, for each age group are also shown.

Figure 3. The percent of male and female patients of various ages with co-morbid bodily pain, psychiatric disorders, alcoholism and nicotine dependence.

Mean percent of those in each age group who reported moderate to very severe pain (panel A), psychiatric disorders (panel B), and met criteria for alcoholism (panel C) or nicotine dependence (panel D).

Table 1.

Bivariate logistic regressions evaluating the influence of gender on the dependent variables shown*

| Females (n=1333) | Males (n=1240) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Source of Primary Opioid | |||

| Dealer | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | 1.38 (1.18–1.62) | <.001 |

| Medical | 1.28 (1.10–1.50) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | .002 |

| Shared | 1.37 (1.17–1.60) | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | <.001 |

| Stolen | 1.34 (1.08–1.67) | 0.75 (0.60–0.92) | .008 |

| Psychiatric Disorder | |||

| Any | 2.11 (1.80–2.47) | 0.47 (0.40–0.56) | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.51 (1.21–1.89) | 0.66 (0.53–0.83) | <.001 |

| Bipolar | 1.57 (1.23–2.10) | 0.64 (0.50–0.82) | <.001 |

| Depression | 1.90 (1.47–2.44) | 0.53 (0.41–0.68) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.91 (0.71–1.17) | 1.10 (0.85–1.41) | .47 |

| Physical Health | |||

| Moderate to Severe Pain in last 7 days | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 0.91 (0.78–1.07) | .26 |

| Substance Use | |||

| Alcohol Dependence | 0.86 (0.73–1.03) | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | .09 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 1.24 (1.01–1.51) | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | .04 |

Numbers in bold are statistically significant (a priori set at P<.01)

Table 2.

Bivariate logistic regressions evaluating the influence of age in the dependent variables shown*

| 18–24 (n=494) | P Value | 25–34 (n=998) | P Value | 35–44 (n=605) | P Value | 45+ (n=476) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Source of Primary Opioid | ||||||||

| Dealer | 2.05 (1.65–2.54) | <.001 | 1.53 (1.30–1.81) | <.001 | 0.75 (0.63–0.91) | .003 | 0.37 (0.30–0.45) | <.001 |

| Medical | 0.41 (0.33–0.50) | <.001 | 0.89 (0.76–1.05) | .16 | 1.28 (1.06–1.53) | .009 | 2.20 (1.79–2.70) | <.001 |

| Shared | 1.23 (1.01–1.49) | .04 | 1.11 (0.95–1.30) | .20 | 0.86 (0.71–1.03) | .10 | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | .07 |

| Stolen | 1.40 (1.09–1.81) | .009 | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | .11 | 0.74 (0.56–0.96) | .03 | 0.72 (0.53–0.97) | .03 |

| Psychiatric Disorder | ||||||||

| Any | 0.68 (0.55–0.83) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.72–0.99) | .03 | 1.20 (1.00–1.45) | .05 | 1.60 (1.30–1.97) | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | .002 | 1.45 (1.15–1.83) | .002 | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | .82 | 0.91 (0.70–1.19) | .51 |

| Bipolar | 0.82 (0.59–1.14) | .23 | 1.00 (0.79–1.28) | .10 | 1.11 (0.85–1.44) | .46 | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | .76 |

| Depression | 0.52 (0.38–0.71) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.89–1.50) | .29 | 1.17 (0.87–1.57) | .30 | 1.25 (0.91–1.71) | .17 |

| Other | 1.80 (1.32–2.45) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.90–1.49) | .27 | 0.82 (0.61–1.10) | .19 | 0.58 (0.41–0.80) | .001 |

| Physical Health | ||||||||

| Moderate to Severe Pain in last 7 days | 0.53 (0.44–0.65) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.67–0.92) | .003 | 1.34 (1.11–1.62) | .002 | 2.12 (1.70–2.64) | <.001 |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| Alcohol Dependence | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | <.001 | 0.65 (0.54–0.78) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.10–1.64) | .004 | 2.33 (1.86–2.91) | <.001 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 0.57 (0.44–0.72) | <.001 | 1.01 (0.83–1.24) | .89 | 1.35 (1.06–1.73) | .02 | 1.30 (0.99–1.71) | .06 |

Numbers in bold are statistically significant (a priori set at P<.01)

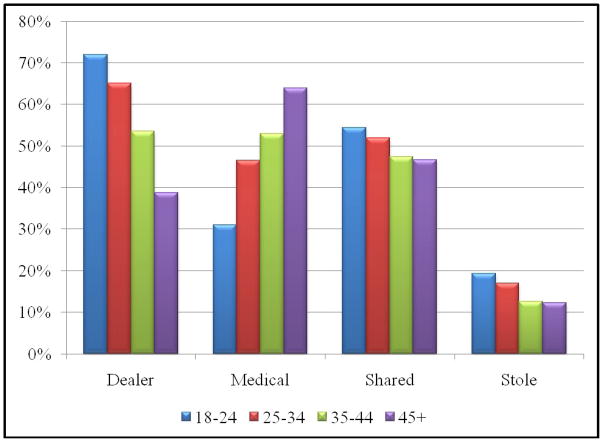

3.3 Main Source of Primary Drug

Figure 4 shows age related differences in the manner of diversion used to obtain prescription opioids. Dealers were used as a source of drugs by over 70% of those 34 or younger, but showed an age related decline such that the odds of individuals over 45 using a dealer were considerably lower than younger ages (Table 2 OR=0.37, p<.001). The odds of men using dealers were greater than females regardless of age (Table 1; OR=1.380, P<.001). In a seemingly compensatory fashion, the use of a doctor’s prescription as a source of drug showed precisely the opposite age-related pattern: very few men and women in the 18–24 year old group used a legitimate medical channel to obtain drugs (Figure 4), but this grew as a function of age such that males (OR=2.31, P<.001) and females (OR=2.15, P<.001) over 45 had much higher odds of using a doctor than younger men or women. Sharing was more common in women than men (Table 1 OR=1.37, P<.001), but showed an age-related non-significant decrease as a source of drugs in both sexes. Theft or other illegal activity to obtain drugs was endorsed by relatively small numbers of young men and women but the odds of women engaging in theft were greater than in men (Table 1 OR=1.34, P<.008) at all ages.

Figure 4. The percent of the treatment sample who used the modes of diversion shown as a function of age.

The percent of those in each age bracket who used the modes of diversion shown. Odds ratios for the influence of gender and age on the disorders shown are contained in tables 1 and 2 respectively.

4. Discussion

Prescription opioid abuse in this country has become endemic over the past 15 years which many believe was given momentum by two significant events: first, the release and subsequent diversion of a sustained release preparation of oxycodone – OxyContin – which was falsely assumed by the company and the FDA to have low abuse potential (Grant et al., 2004; Schulden, Thomas & Compton, 2009; Cicero, Inciardi & Muñoz, 2005; General Accounting Office, U.S., 2003; Manchikanti, Fellows, Ailinani & Pampati, (2010), Sproule, Brands, Li, & Catz-Biro, 2009); and, second, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) report that named pain as the fifth vital sign and recommended that opioids be used much more (Manchikanti & Singh, 2008; Okie, 2010). This advice was obviously well-received: the use of opioids surged after this highly publicized report which inevitably resulted in some diversion for non-therapeutic purposes (Cicero, Surratt & Inciardi, 2007). Aside from the debate on enabling factors, there is little doubt that prescription opioid abuse now dwarfs heroin abuse and, at least some other illegal drug use, as a public health problem in this country.

Our data show that moderate to severe non-withdrawal related bodily pain – that greatly limited social contacts and work – was common in most of those entering treatment: 45% of those 18–24 years reported moderate to severe pain. However, the incidence of this intense pain grew to well over 70% in individuals 45 or older. The mental health status of men and, particularly women, entering treatment was even worse. Depression, anxiety and poly-substance abuse (alcoholism and nicotine dependence) were already prevalent in our youngest sample at rates far greater than population norms, but mental health deteriorated rapidly, with the result that the vast majority of those over 45 were suffering psychiatric disorders. While these observations are consistent with prior reports of co-morbidity in substance misusers (McCabe, Cranford & West, 2008; Skurtveit, Furu, Selmer, Handal & Tverdal, 2010; Sullivan, Edlund, Steffick & Unützer, 2005; Sullivan, Edlund, Zhang, Unützer & Wells, 2006; Cicero et al., 2009), the age and gender relatedness of these effects has not to our knowledge been fully appreciated until now. What seems clear is that treatment, prevention and intervention programs would seem to be destined to fail if age and gender are not carefully considered in tailoring these efforts to specific populations.

Given the poor health we observed, it seems reasonable to postulate that disability, serious medical issues and/or other factors (e.g. economic, risk-aversion in seeking drugs – see below) would lead to the forced cessation of drug use in long-term substance abusers (i.e. “burnout”). If this is true, then one might expect, as we found, an age related drop in drug seeking behavior and in those seeking drug-abuse treatment. However, it seems far more likely that, as they age, treatment for the medical complications associated with substance abuse (e.g. cognitive impairments, psychiatric disorders, organ failure and so forth) may become much more clinically relevant than substance abuse treatment per se. Thus, a drop in the number of elderly people seeking drug treatment should not necessarily be assumed to indicate that the disease has run its course, but that aging addicts end up in medical specialty treatment programs rather than drug treatment centers. In this connection, it should be noted that the co-morbid conditions often associated with or caused by substance abuse are generally covered by insurance companies, whereas the public and private health insurance industry has become increasingly reluctant to cover substance abuse treatment per se in nearly any form. Thus, it could be that it is more economical and practical for patients and hospitals to treat the medical complications associated with abuse but not the underlying problem itself as the population of abusers age. We know of no studies in which this hypothesis has been systematically addressed.

As mentioned above, our study was not longitudinal and it is therefore quite possible that the huge surge of youthful opioid abusers who began using drugs in the 1993–2010 time-frame have not yet reached the age of 40. If this hypothesis is correct, the number of elderly people seeking treatment should continue to rise over the next 5–10 years which will represent a huge burden on drug treatment centers that are generally ill-equipped to handle the plethora of serious psychiatric and physical ailments found in aging opioid abusers.

As discussed above, we found in agreement with an earlier study that age and gender influenced the modes of diversion utilized to siphon drugs from medically appropriate channels to the illicit marketplace (Cicero et al., 2010b). At any age, women were much less likely to use a dealer than men and, as they aged, both men and women were also more inclined to use medical channels as their primary source of drugs rather than dealers whose use predominates in younger men. These data could reflect the fact that women are much more risk-averse than men and that, as they age, both men and women’s risk aversion makes doctors a much safer bet than dealers. However, other possibilities exist. While it is certainly less risky to use a doctor than a dealer, the enhanced use of medical channels could be due to the fact that it is far easier for elderly patients with pain to get a doctor’s prescription for an analgesic than it would be for younger males and females to do so. In addition, it is also possible that it is much more economical, provided private or government funded insurance is available, to deal with a doctor rather than a dealer. Thus, at least some of the age-related inversion between dealers and doctors may be due to ease of access and economic concerns. Whichever explanation is correct, family practitioners, who prescribe the bulk of all opioids in the United States, should be just as cautious about potential opioid misuse in the elderly as they might be for younger patients.

The largest confound in our studies is whether the co-morbidity we observed is caused by the lengthy punishment inflicted by heavy substance abuse or if substance abuse is merely a symptom of a much larger constellation of psychiatric and physical problems, which grow worse with age, in a highly vulnerable subgroup of the general population. This confound probably can never be clearly resolved, but there is ample evidence (Schulden, Thomas & Compton, 2009; Manchikanti, Fellows, Ailinani & Pampati, 2010; McCabe, Cranford & West, 2008; Rogers & Copley, 2009; Skurtveit, Furu, Selmer, Handal & Tverdal, 2010), including the present data, that adolescents and young adults who misuse opioids and other drugs have clear psychiatric and substance abuse (e.g. alcoholism) issues long before their misuse of opioids begins. This suggests that substance abuse is merely one symptom of a much larger constellation of problems, and is not the causal factor in the poor physical and mental health we observed. However, it is difficult not to conclude that the deterioration in health over time is due, in some appreciable measure, to poor life-style choices including excessive opioid, alcohol and other drug abuse issues.

There are limitations in our study. All of our surveys were self-administered and thus they have most of the problems associated with these methods, particularly the inability to follow up answers with additional questions to clarify any ambiguities and truthfulness (Aquilino & LoSciuto, 1990; Aquilino, 1994; Hochstim, 1967). A second limitation is that our study population was confined to those entering treatment in many cases for the fourth or fifth time. Thus, this population, and their profound problems with drugs and other psychopathology may be very different than less ill, “recreational” drug users. While all of these possibilities need to be kept in mind in interpreting our results, the anonymity provided by the self-administered questionnaire has been shown to produce much more candid and valid drug related responses than interviewer- elicited information regarding substance abuse issues. Moreover, in a recently published study it was found that the results of self-administered surveys and face-to-face interviews regarding sources of diversion were almost perfectly correlated (Cicero et al., 2010b).

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Supported in part by NIDA grants DA020791, DA 21330 (TJC); DA21330 (SK); and an unrestricted research grant from Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: All of the authors had full access to all of the data in the study and assisted in the design of the study, collection of data and preparation of this report. Dr. Theodore J. Cicero took the lead in the efforts and is ultimately responsible for the integrity of the data, accuracy of the data analysis, overall study results and drafting the paper.

Conflict of Interest: With the exception of Matthew Ellis, all of the authors serve as consultants to the non-profit post-marketing surveillance system Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS®) System which collects subscription fees from 11 pharmaceutical firms. None of the subscribers would appear to have any interest in the outcome of this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aquilino W, LoSciuto L. Effect of interview mode on self-reported drug use. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1990;58:210–240. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aquilino W. Interview mode effects in surveys of drug and alcohol use. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1994;54:362–395. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyles S. CDC: Alarming increase in methadone deaths. Deaths from opioid painkillers have tripled since 1999. WebMD Health News. 2009 September;30:2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, Sullivan MD. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(16):1425–1432. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckwalter KC. Recruitment of older adults: an ongoing challenge. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009 Oct;2(4):265–6. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090816-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai R, Crane E, Poneleit K, Paulozzi L. Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs in the United States, 2004–2008. Journal of Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 2010;24(3):293–297. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2010.503730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canfield MC, Keller CE, Frydrych LM, Ashrafioun L, Purdy CH, Blondell RD. Prescription Opioid Use among Patients Seeking Treatment for Opioid Dependence. J Addict Med. 2010 Jun 1;4(2):108–113. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181b5a713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicero TJ, Lynskey M, Todorov A, Inciardi JA, Surratt HL. Co-morbid pain and psychopathology in males and females admitted to treatment for opioid analgesic abuse. Pain. 2008 Sep 30;139(1):127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cicero TJ, Wong G, Tian Y, Lynskey M, Todorov A, Isenberg K. Co-morbidity and utilization of medical services by pain patients receiving opioid medications: data from an insurance claims database. Pain. 2009 Jul;144(1–2):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Paradis A, Ortbal Z. Determinants of fentanyl and other potent μ opioid agonist misuse in opioid-dependent individuals. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2010a;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cicero TJ, Dart RC, Inciardi JA, Woody GE, Schnoll S, Muñoz A. The development of a comprehensive risk-management program for prescription opioid analgesics: researched abuse, diversion and addiction-related surveillance (RADARS) Pain Med. 2007 Mar;8(2):157–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicero TJ, Kurtz SK, Surratt HL, Ibanez GE, Ellis MS, Levi-Minzi MA, Inciardi JA. Multiple Determinants of Specific Modes of Prescription Opioid Diversion. 2010b doi: 10.1177/002204261104100207. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cicero TJ. Prescription Drug Abuse and its Relationship to Pain Management. Advances in Pain Management 2008. 2008;2(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicero TJ, Surratt H, Inciardi JA. Relationship between therapeutic use and abuse of opioid analgesics in rural, suburban and urban locations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2007;16(8):827–840. doi: 10.1002/pds.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A. Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002–2004. J Pain. 2005 Oct;6(10):662–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dart RC. Monitoring risk: Post marketing surveillance and signal detection. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105(Suppl 1):S26–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta N, Mandl KD, Brownstein JS. Breaking the news or fueling the epidemic? Temporal association between news media report volume and opioid-related mortality. PLoS One. 2009 Nov 18;4(11):e7758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan MY, Devries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Risks for opioid abuse and dependence among recipients of chronic opioid therapy: Results from the TROUP Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 Jul 13; doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 2003;3(1978):235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.General Accounting Office, U.S. OxyContin Abuse and Diversion and Efforts to Address the Problem [Report to Congressional Requesters, #GAO-04-110] Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Saplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawthorne G, Osborne RH, Taylor A, Sansoni J. The SF-36V2 Version 2: critical analyses of population weights, scoring algorithms and population norms. Qual Life Res. 2007 May;16(4):661–73. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9154-4. Epub 2007 Feb 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochstim J. A critical comparison of three strategies of collecting data from households. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1967;62:976–989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manchikanti L, Singh A. Therapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician. 2008 Mar;11(2 Suppl):S63–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapuetic use, abuse and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13(5):401–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, West BT. Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: results from two national surveys. Addict Behav. 2008 Oct;33(10):1297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melberg HO, Humphreys K. Ineligibility and refusal to participate in randomised trials of treatments for drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010 Mar;29(2):193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010 Nov 18;363(21):1981–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Jr, Turner BJ, Moore AA, Olkhovskaya Y, Amanfo L, Reid MC. Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Jul;58(7):1353–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02920.x. Epub 2010 Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulozzi LJ, Ballesteros MF, Stevens JA. Recent Trends in Mortality from Unintentional Injury in the United States. Journal of Safety Research. 2006;37:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulozzi LJ, Annest J. Unintentional Poisoning Deaths – United States, 1999–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers PD, Copley L. The nonmedical use of prescription drugs by adolescents. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2009 Apr;20(1):1–8. vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulden JD, Thomas YF, Compton WM. Substance abuse in the United States: findings from recent epidemiologic studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009 Oct;11(5):353–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skurtveit S, Furu K, Selmer R, Handal M, Tverdal A. Nicotine Dependence Predicts Repeated Use of Prescribed Opioids. Prospective Population-based Cohort Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Jun 1; doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sproule B, Brands B, Li S, Catz-Biro L. Changing patterns in opioid addiction: characterizing users of oxycodone and other opioids. Canadian Family Physician. 2009;55(1):68–69. 69.e1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. The DAWN Report: Trends in Emergency Department Visits Involving Nonmedical Use of Narcotic Pain Relievers. Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unützer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2087–93. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Unützer J. Regular use of prescribed opioids: association with common psychiatric disorders. Pain. 2005;119:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1996;60:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric; 2001. [Google Scholar]