Abstract

Aim

To assess whether the BI-RADS classification in MR-Mammography (MRM) can distinguish between benign and malignant lesions.

Material and method

207 MRM investigations were categorised according to BI-RADS. The results were compared to histology. All MRM studies were interpreted by two examiners. Statistical significance for the accuracy of MRM was calculated.

Results

A significant correlation between specific histology and MRM-tumour-morphology could not be reported. Mass (68%) was significant for malignancy. Significance raised with irregular shape (88%), spiculated margin (97%), rim enhancement (98%), fast initial increase (90%), post initial plateau (65%), and intermediate T2 result (82%). Highly significant for benignity was an oval mass (79%), slow initial increase (94%) and a hyperintense T2 result (77%), also an inconspicuous MRM result (77%) was often seen in benign histology. Symmetry (90%) and further post initial increase (90%) were significant, whereas a regional distribution (74%) was lowly significant for benignity.

Conclusion

On basis of the BI-RADS classification an objective comparability and statement of diagnosis could be made highly significant. Due to the fact of false-negative and false-positive MRM-results, histology is necessary.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Breast tumours, Breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women aging more than 40 years [1]. In early studies magnetic resonance imaging of the breast (MRM) was used as a tool to further characterize suspicious clinical or mammographic examinations. However indications for MRM are high risk patients, preoperative estimation of the extent of the disease in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, especially lobular invasive carcinomas, patients with breast implants, cancer of unknown primary and the differentiation between scar and tumour recurrence [2–7]. Breast cancers enhance brightly compared to normal breast tissue and normal biopsy scars, which enhance little or even not at all [8]. However, MRM techniques vary across the world. In 1999 the “Lesion Diagnosis Working Group” devised the recommendations for standard MRM terms based on architectural features described by the ACR (American College of Radiology) BIRADS system (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) [8, 9]. Furthermore, Ikeda et al. developed and standardized the reproducibility in a lexicon for reporting contrast enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging examinations. This lexicon adapted American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System terminology for MRM reporting, including recommendations for reporting clinical history, technical parameters for MRM, descriptions for general breast composition, morphological and kinetically characteristics of mass lesions or regions of abnormal enhancement, overall impression and management recommendations [9, 10]. Consequently, the aim of this study was to assess whether a BI-RADS associated MRM algorithm delivers a clinical significant prognosis for the diagnosis of breast tumours.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

In a consecutive series between April 2004 and January 2008, 207 female patients with histological proven breast lesions have been evaluated. Histology was predominantly reached by either preoperative wire localization in MRM or by ultrasound or stereotactic guided biopsies. In case of malignancy reference standard was the pathology after surgery. All of the patients have had a preoperative MR mammography. In addition all patients underwent a digital mammography (Senographe 2000D, GE Medical Systems). Patient details were recorded with the purpose to identify the mammograms and for accessing demographic information. From the request card, logbooks and hospital database, record was made of age, referring speciality, date of admission, and anamnesis. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The median age of the study group was 54 years. Due to different indications with regards to suspicious breast findings, including a palpable mass, patients with high risk, and referrals from other screening investigations like mammography or ultrasound, all patients were referred from our academic Breast Center. 112 patients had a histological proven breast cancer and 95 patients had a histological proven benign tumour (Table 1). In case of a benign lesion the mean follow up interval was 6 months.

Table 1.

Distribution of the histological malignant and benign lesions

| Carcinomas | Number (n) | Benign Tumors | Number (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive ductal carcinoma, IDC | 32 | Ductal hyperplasia, DH | 21 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma, ILC | 18 | Fibroadenoma, FI | 18 |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ, DCIS | 17 | Fibrocystic changes, FZM | 16 |

| Tubular carcinoma, TU | 10 | Papilloma, PA | 9 |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ, LCIS | 9 | Benign not categorisable, A | 8 |

| IDC + Extensiv intraductal carcinoma, EIC | 8 | Adenosis, SA | 13 |

| Ductal and lobular carcinoma, DLC | 6 | Phyllodes Tumor, PB | 3 |

| Mucinous carcinoma, MUC | 5 | Radial scar, RN | 2 |

| Carcinosarcoma, S | 2 | Atypical Hyperplasia, AH | 2 |

| Others | 5 | Others | 3 |

| Total | 112 | Total | 95 |

MRM technique

All 207 MRM examinations were performed with the patient prone in a 1.5-T commercially available system (Symphony and Sonata, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a dedicated surface breast coil. The standardized imaging sequence started with a bilateral axial T2-weighted turbo spin-echo sequence (GRAPPA factor 2; 8.900/207; flip angle 90°, spatial resolution 0.8 × 0.7 × 3 mm; acquisition time 2 min 15 s) and a bilateral turbo spin-echo inversion recovery sequence with reconstruction (GRAPPA factor 2; 8.420/70; inversion time 150 ms; flip angle 180°, spatial resolution 1.7 × 1.4 × 3 mm; acquisition time 2 min and 33 s) were performed in identical slice positions. Afterwards an unenhanced axial T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence (Flash 2D, GRAPPA factor 2; TR/TE 113/5; flip angle 80°; spatial resolution 1.1 × 0.9 × 3 mm; acquisition time 1 min per measurement) was performed. An intravenous bolus injection of 0.1 mmol/kg body weight gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) was used at 3 ml/s with an automatic injector and followed immediately by 20 ml of saline solution with the same injection rate. 30 s after the administration of contrast medium, dynamic MRM was performed with the same parameters and identical tuning conditions for totally 7 measurements. The contrast-enhanced images were subsequently subtracted from the unenhanced images. On the subtraction images the region of interests (ROI’s) were achieved on a pixel-by-pixel basis and signal-intensity curves were analysed. The kinetic behaviour of the lesion was analyzed by ROI in the most enhancing area. Also maximum intensity projections (MIP) were displayed.

Image interpretation

The MRM studies were interpreted by two examiners. One experienced and one trained observer classified the selected MR images anew, without knowledge of pathology. Neither was involved in rating the initial MR images, and both were blinded to the initial report and to the results of the histological and mammographic examinations. The rating was performed in consensus. In the case of different rating, the case was discussed until agreement was reached. All investigations were categorised according to BI-RADS: Mass/shape, mass/margin, mass/enhancement, non-mass/distribution, non-mass/internal enhancement, symmetry, kinetic curve assessment (24 missing) and T2-weighting (35 missing). These results were compared to histology. Statistical significance for the accuracy of MRM was calculated.

Reference standard

The authors chose the results of the histological examination as the reference standard for lesion evaluation. Findings could either be malignant or benign, and the type of tumour was recorded. All histological examinations were conducted by board-certified breast pathologists at the institute of pathology of our university hospital.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Data were recorded in a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Statistical analysis was performed with the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests using statistical software (SSPS, and MedCalc). According to the level of significance (two-sided p-value) asterisks were distributed:

*** p-value < 0.0005 (double p-value < 0.001, “highly significant”)

** p-value < 0.005 (double p-value < 0.01, “significant”)

* p-value < 0.025 (double p-value < 0.05, “faintly significant”)

Results

Comparison of benign and malignant tumours

The following tables show the morphological differences between malignant and benign tumours. For analyzing reasons we separated into mass and non-mass lesions. It was proven that 70.5% of the malignant tumours were categorised as mass, 23.2% as non-mass, and 7 malignant tumours were inconspicuous at MRM (6.3%; not definitely detected in MRM, but with positive mammography or ultrasound investigation, and therefore with histological proven breast cancer). Out of the 95 benign tumours only 40% delivered a mass-diagnosis, 35.8%, and 24.2% were considered as inconspicuous at MRM (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore particular attention was paid on the histopathological diagnosis with regards to the specific BI-RADS criteria. The specific morphology is presented in the following tables.

Table 3.

Margin of the mass enhancement in histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margin | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Smooth | 3 | 16 | 19 | 0.0004*** |

| Irregular | 47 | 20 | 67 | 0.0010** |

| Spiculated | 29 | 1 | 30 | 0.0000*** |

Table 4.

Internal enhancement of the mass enhancement into histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancement | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Rim enhancement | 43 | 1 | 44 | 0.0000*** |

| Heterogeneous | 35 | 23 | 58 | 0.1664 |

| Homogeneous | 1 | 8 | 9 | 0.0092* |

| Heterogeneous + internal septation | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.0192* |

Interpretation and reporting of MRM findings on the basis of the BI-RADS classification

Focus

In this matter it was not possible to give a significant statement, because only one malignant and one benign tumour showed a focal enhancement.

Mass

Shape

The correlation of shape and diagnosis in mass enhancement is shown in Table 2 and gives the following results. 60 out of 68 (88.2%) irregular formed masses are malignant. 11 out of 14 (78.6%) oval shaped tumours have a benign histology. 14 of 25 (56%) lobulated tumours were categorised as benign. Considering the group of 112 malignant tumours, 60 (53.6%) out of them are formed irregularly.

Table 2.

Shape of the mass enhancement in histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Round | 5 | 5 | 10 | 0.5196 |

| Irregular | 60 | 8 | 68 | 0.0000*** |

| Lobulated | 11 | 14 | 25 | 0.1927 |

| Oval | 3 | 11 | 14 | 0.0111* |

Margin

Correlation between margin and diagnosis in mass enhancement is given in Table 3. Most of the malignant lesions have an irregular (42%) or spiculated (25.9%) margin. Whereas 21.1% of benign lesions are of irregular margin, only 1.1% are spiculated. A smooth margin refers to benignity as 16 out 19 tumours of smooth margin were histological proven benign and only 3 were malignant.

Enhancement

Table 4 shows that the majority of the malignant tumours had rim enhancement. The sheet points out, that 43 out of 44 tumours (97.7%) with rim enhancement were categorised to the malignant group. Comparing the heterogeneous forms of enhancement, 35 tumours were into the malignant and 23 into the benign group. Homogeneous enhancement was seen in 88.9% (8/9 cases) in tumours out of the benign group. Internal septation refers to benignity (Figs. 1–4).

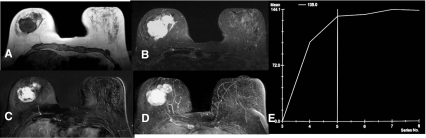

Fig. 1.

Mass enhancement into the right breast (lobulated shape, irregular margin, heterogeneous enhancement) with hyperintensic T2-result. T1-weighting (a), T2-weighting (b), subtraction (c), MIP-Reconstruction (d), Kinetic curve assessment (e). Histology: Phyllodes tumour

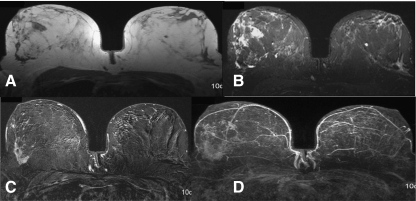

Fig. 4.

Mass enhancement (irregular shape, irregular margin, heterogeneous) in the right breast with intermediate signal in T2. T1- weighting (a), T2- weighting (b), subtraction (c), MIP-Reconstruction (d). Histology: Radial scar

Non-mass

Distribution

There were only a few differences concerning non-mass between the two groups. However, all lesions with ductal and segmental distribution were categorised malignant. On the other hand, all focal lesions showed benign potential. For regional enhancement a mean significance for benignity was reported (Table 5, Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Distribution of the non-mass like-enhancement into histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Non-mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Diffuse | 14 | 10 | 24 | 0.4133 |

| Multiple regions | 4 | 6 | 10 | 0.2761 |

| Regional | 5 | 14 | 19 | 0.0101* |

| Ductal | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.0445 |

| Segmental | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.1564 |

| Dendritic | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5411 |

| Linear | 5 | 2 | 7 | 0.2958 |

| Focal | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.0950 |

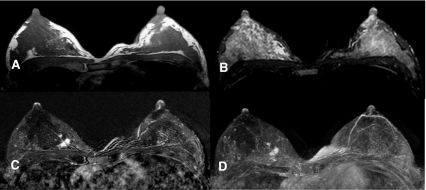

Fig. 3.

Non-mass like enhancement into the left breast (regional, heterogeneous enhancement), hyperintensic T2-result. T1- weighting (a), T2- weighting (b), Subtraction (c). Histology: Ductal hyperplasia

Internal enhancement

28 of 112 malignant tumours (25%) had a heterogeneous central enhancement. Moreover, a stippled enhancement was predominantly seen in benign tumours (Table 6).

Table 6.

Internal enhancement of the non-mass-like enhancement in histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Non-mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central enhancement | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Heterogeneous | 28 | 17 | 45 | 0.1431 |

| Homogeneous | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.7085 |

| Stippled | 5 | 12 | 17 | 0.0298 |

| Clumped | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0.4226 |

| Reticular/Dendritic | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.2515 |

Symmetry

Table 7 shows the malignant and benign lesions by means of their symmetry. The table indicates that the malignant as well as the benign tumours seemed to appear asymmetrically. Nevertheless, in 9 out of 10 cases symmetry leads highly significant to a benign tumour.

Table 7.

Symmetry for histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Non-mass | Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Number (n) | % | Number (n) | % | ||

| Symmetric | 1 | 0,9% | 9 | 9,5% | 10 | 0.0044** |

| Asymmetric | 104 | 92,9% | 63 | 66,3% | 167 | 0.0000*** |

| Inconspicuous | 7 | 6,3% | 23 | 24,2% | 30 | 0.0002*** |

| Total | 112 | 100,0% | 95 | 100,0% | 207 | |

Kinetic

Into the malignant group 69.6% (78/112 tumours) of the lesions had a medium initial increase of the kinetic curve. Only 16.1% of the malignant tumours (18/112 cases) had a fast initial increase. 18 out of 20 tumours (90%) with a fast kinetic were grouped as malignant (Table 8).

Table 8.

Initial kinetic curve assessment (Kinetic) for histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic/Initial | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Slow | 1 | 15 | 16 | 0.0000*** |

| Mean | 78 | 40 | 118 | 0.0000*** |

| Fast | 18 | 2 | 20 | 0.0004*** |

In the benign group 42.1% of the tumours (40/95 cases) showed a medium initial ascent of the curve. Out of the 16 tumours with slow initial increase 93.7% (15 tumours) were highly significant categorised as benign (Table 8, Fig. 1).

The post initial increase of the signal for malignant and benign tumours is shown in Table 9. A plateau of the kinetic curve was seen in 70.5% (79/112 cases) into malignant lesions, and a wash-out was documented in 15.2% (17 cases). Out of a total number of 121 tumours with a plateau, 65.2% (79 cases) were categorised as malignant. In addition 77.3% (17/22 cases) with wash-out were malignant. Conversely, a further increase of the kinetic curve was in 90% a marker for a benign tumour (Table 9).

Table 9.

Post initial kinetic curve assessment (Kinetic) for histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic/Post initial | Number (n) | Number (n) | ||

| Plateau | 79 | 42 | 121 | 0.0000*** |

| Wash-out | 17 | 5 | 22 | 0.0170* |

| Further increase | 1 | 9 | 10 | 0.0044** |

T2-weighting

It was noticeable that 77 (69%) out of the malignant tumours had an intermediate T2-signal. This argued in 81.9% for malignancy. By comparison 37 of the benign tumours (38.9%) had a hyperintense appearance (Table 10, Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Table 10.

T2- weighting for histological proven malignant and benign tumors

| Malignant | Benign | Total | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2-result | Number (n) | % | Number (n) | % | ||

| Hyperintensic | 11 | 9% | 37 | 38,9% | 48 | 0.0000*** |

| Intermediate | 77 | 69% | 17 | 17,9% | 94 | 0.0000*** |

| Inconspicuous | 7 | 6% | 23 | 24,2% | 30 | 0.0002*** |

| Missing | 17 | 15% | 18 | 18,9% | 35 | 0.2958 |

| Total | 112 | 100,0% | 95 | 100,0% | 207 | |

Fig. 2.

Non-mass like enhancement into the right breast (regional, heterogeneous enhancement), intermediate T2-result. T1- weighting (a), T2- weighting (b), subtraction (c), MIP-Reconstruction (d). Histology: Invasive lobular carcinoma

Discussion

This study demonstrates a high value of a BI-RADS associated MRM algorithm to deliver a high accuracy for the diagnosis of breast tumours. The major finding of our study results which compared MRM findings with histology, is that on the basis of the BI-RADS classification an objective comparability and statement of diagnosis could be made highly significant.

Gutierrez et al. evaluated the predictive features of BI-RADS lesion characteristics and the risk of malignancy for mammographic and clinical occult lesions detected initially on 1.523 MRMs. They concluded that combinations of BI-RADS lesion descriptors can predict the probability of malignancy for MRM masses but not for non-mass like enhancement [2]. In case of mass lesions, their results act in concert with our data. We showed as well, that specific BI-RADS criteria are strong and significant predictors for malignancy in unsuspected MRM mass lesions. Such confirmation led in about 65% of cases to a malignant diagnosis (Tables 2, 3 and 4). However, the combination of several marker and characteristics is useful to determine the likelihood of malignancy. In contrast to the results by Gutierrez et al. we could observe, that BI-RADS descriptions were as well predictive for malignancy of otherwise unsuspected MRM non-mass like lesions. Table 5 shows for example, that a non-mass like enhancement with ductal or segmental distribution was in 100% malignant.

In addition, our data showing particular BI-RADS lexicon descriptions to be strong predictors of malignancy, support recent work by Liberman et al. Their group investigated 427 lesions by MRM with dutcal enhancement. 80% out of the benign tumours had a plateau into the contrast-enhancement dynamic and 89% an isointensic signal into the T2-weighting [11]. Tozaki et al. described the PPV and NPV of focal masses. The main criterion for a malignant lesion was heterogeneous enhancement (96%), while benign tumours showed inconspicuous margin and form in 82%. The highest PPV for a malignant enhancement had lesions with spiculated margin (100%), irregular form (97%) and a heterogeneous enhancement without internal septation (97%). The highest PPV for benignity was found in tumours with oval mass (88%), homogeneous mass-enhancement (87%) and heterogeneous mass-enhancement with internal septation (86%). Combination of several specifications lead to a PPV of 100% for tumours with spiculated rim as well as for tumours with heterogeneous enhancement and post initial wash-out if those lesions were out of the group with oval margin [12].

However, non-mass like enhancement was identified as a challenging subgroup causing a high proportion of false-positive diagnoses at diagnostic MRM. In several cases this lead to unnecessary biopsy [13]. In a further study by Tozaki et al. they investigated tumours without mass findings and PPVs were as well compared with each other. They concluded that most of the benign tumours were linear (50%) and had a homogeneous internal pattern (42%). In contrast, most of the malignant tumours were segmental (56%), heterogeneous (44%) and had a rim enhancement. The highest PPV had carcinomas with a segmental distribution (100%), rim enhancement (100%) and grouped internal compaction (88%) [14]. This acts in concert with our results. Mass enhancement (68%) was significant for malignancy. This was confirmed by high significance (Table 2). A similar picture was shown for tumours without mass enhancement, 56.6% of them were benign. In this context, it has to be mentioned that 23% of the inconspicuous MR mammograms had malignant and 77% benign lesions (Table 2). Furthermore, our results indicated that 88% of the tumours with irregular shape were highly significant malignant. Those tumours with an oval or lobulated shape were in 78.6% (oval) and 56% (lobulated) benign. However, in these cases only a mean significance was reached. This leads to the conclusion that a lesion with an irregular shape is with the utmost probability malignant. In contrast, tumours with oval or lobulated shape suspect to be benign, without verifiable significance (Table 2). This is absolutely in line with former studies [11–14].

There was a strong tendency for tumours with irregular or spiculated margins to be malignant. Highly significant for benignity were tumours with smooth margin (84.2%; Table 3). If a lesion showed rim enhancement it was highly significant malignant (97.7%). Tumours were significantly benign if there was a homogeneous enhancement (88.9%) or a heterogeneous enhancement with internal septation (100%; Table 4).

A non-mass like lesion with ductal or segmental distribution was in 100% malignant. Diffuse distribution was commonly seen within malignant tumours. However, it was not possible to constitute a distinct statistical statement (Table 5).

This corresponds to the study by Baltzer et al. which aimed to identify criteria for false-positive MRM findings in clinical practice. They concluded that non-mass like enhancement was the main cause for those findings. Furthermore, in their analysis the BI-RADS descriptions were not sufficient for differentiating malignant and benign non-mass like enhancement [15].

Evidence-based algorithms are needed to guide the radiologist through image assessment and to describe morphologic features. Thus, concerning the form of internal enhancement the range was essentially exceeded. 28 out of the malignant tumours showed heterogeneous enhancement, this lead to significance to malignancy only in 62%. Marks for benignity were reticular (75%) and stippled/punctuated enhancement (70.58%). Whereas only 3.2% and 12.6% out of all benign tumours showed this pattern. Consequently, a significant statement could not be announced (Table 6). In addition, symmetry was very important to deliver a prognosis. 90% out of the symmetric appeared enhancement (9.5% of the benign tumours) were significantly benign. Asymmetric appeared enhancement was highly significant for malignancy (Table 7).

A number of investigations have been conducted to introduce and describe the kinetic features of breast lesions [12, 13]. Tumours with a mean or fast signal increase had a high significance to be malignant in 66% or 90%. It was well-defined, that tumours with a slow signal increase were highly significant benign (in 94%). Furthermore, it was shown that lesions with a plateau or a wash-out were significant malignant. Only 44% of the benign group showed a plateau (Tables 8 and 9). Within the T2-weighting a strong tendency was seen, that tumours with an intermediate signal were in 82% highly significant malignant. On the other hand, a hyperintense signal in the T2- weighting was in 77% an indicator for benignity (Table 10).

Finally we conclude, based on the BI-RADS classification, that an objective comparability and highly significant statement of diagnosis can be made [2–6, 12–16]. The combination of several marker and characteristics is still essential to determine malignancy. Due to numerous false-negative and false-positive MRM-results histology is still essential.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Aubard Y, Genet D, Eyraud JL, et al. Impact of screening on breast cancer detection. Retrospective comparative study of two periods ten years apart. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;23:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez RL, DeMartini WB, Eby PR, et al. BI-RADS lesion characteristics predict likelihood of malignancy in breast MRI for masses but not for non mass like enhancement. AJR. 2009;193:994–1000. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunes LW, Schnall MD, Orel SG, et al. Breast MR imaging: interpretation model. Radiology. 1997;202:833–841. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes LW, Schnall MD, Orel SG. Update of breast MR imaging architectural interpretation model. Radiology. 2001;219:484–494. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma44484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnall MD, Blume J, Bluemke DA, et al. Diagnostic architectural and dynamic features at breast MR imaging: multicenter study. Radiology. 2006;238:42–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381042117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benndorf M, Baltzer PA, Vag T, et al. Breast MRI as an adjunct to mammography: Does it really suffer from low specificity? A retrospective analysis stratified by mammographic BI-RADS classes. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:715–721. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.497164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obenauer S, Sohns C, Werner C, et al. Computer-aided detection in full-field digital mammography: detection in dependence of the BI-RADS categories. Breast J. 2006;12:16–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Radiology: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). 3. Auflage, Reston 1998

- 9.Schnall MD, Ikeda DM. Lesion diagnosis working group on breast MR. Radiology. 1999;153:243–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda DM, Hylton MN, Kinkel K, et al. Development, standardization, and testing of a lexicon for reporting contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging studies. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:889–95. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberman L, Morris EA, Dershaw DD, Abramson AF, Tan LK, et al. Ductal enhancement on MR imaging of the breast. AJR. 2003;181:519–525. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.2.1810519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tozaki M, Fukuda K. High-spatial-resolution MRT of non-mass like breast lesions: interpretation model based on BI-RADS MRT descriptors. AJR. 2006;187:330–337. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhl CK. Current status of breast MR imaging. Part 2. Clinical applications. Radiology. 2007;244:672–691. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443051661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tozaki M, Igarashi T, Fukuda K. Positive and negative predictive values of BI-RADS-MRT, descriptors for focal breast masses. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2006;5:7–15. doi: 10.2463/mrms.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltzer PAT, Benndorf M, Dietzel M, et al. False-positive findings at contrast-enhanced breast MRI: a BI-RADS descriptory study. AJR. 2010;194:1658–1663. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tozaki M, Igarashi T, Fukuda K. Breast MRT using the VIBE sequence: clustered ring enhancement in the differential diagnosis of lesions showing non-masslike enhancement. AJR. 2006;187:313–321. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]