Abstract

Objective We have limited knowledge about the specific elements in an occupational rehabilitation programme that facilitate the process leading to return to work (RTW) as perceived by the patients. The aim of the study was to explore individual experiences regarding contributing factors to a successful RTW, 3 years after a resident occupational rehabilitation programme. Methods The study is based on interviews of 20 individuals who attended an occupational rehabilitation programme 3 years earlier. Ten informants had returned to work (RTW) and ten were receiving disability pension (DP). Data were analysed by systematic text condensation inspired by Giorgi’s phenomenological analysis. Results The core categories describing a successful RTW process included positive encounters, increased self-understanding and support from the surroundings. While the informants on DP emphasized being seen, heard and taken seriously by the professionals, the RTW group highlighted being challenged to increase self-understanding that promoted new acting in every-day life. Being challenged on self-understanding implied increased awareness of own identity, values and resources. Support from the surroundings included support from peer participants, employer and social welfare system. Conclusion Successful RTW processes seem to comprise positive encounters, opportunities for increased self-understanding and support from significant others. An explicit focus on topics like identity, own values and resources might improve the outcome of the rehabilitation process.

Keywords: Occupational rehabilitation, Increased self-understanding, Good encounters, Support from significant others

Introduction

The high number of people on long-term sick leave and disability benefits has increased the need for occupational rehabilitation during the last years. Investigations of return-to-work (RTW) processes after sick-listing and possible predictive and facilitating factors have led to increased knowledge in this area [1]. Prognostic factors for RTW, as well as maintaining factors for being on long-term sick leave, are complex and multidimensional. A number of socio-demographic, individual and environmental factors have been linked to increased RTW rate [1–5]. Clinical work and research has traditionally focused on treatment of disease and pain reduction. There has however been a shift from medically determined models, to increased focus on the importance of the individual, workplace, economic and social factors in the genesis of disability and RTW processes [6–8]. There is some evidence that early, multidisciplinary interventions combined with work-place interaction may be of importance [9–12]. Despite this knowledge, the overall rates of work disability have not changed significantly, and a large number of patients will not return to work after they have completed the rehabilitation. Identifying specific elements of the rehabilitation programmes that may be of significant importance for the patients in their RTW efforts may be helpful in designing such programmes.

More than 50% of those absent from work are diagnosed with musculoskeletal or psychological problems [13]. A large proportion of the health problems that leads to long-term sick leave are often characterized by a high degree of co morbidity; i.e. anxiety and depression are often reported with different musculoskeletal problems [14–16]. Co morbidity impedes RTW and increase the risk of permanent disability [17–19]. Psychological distress and low self-estimated expectancy of RTW predicts a poor outcome [20, 21]. The causes of long-term sick leave are individual and complex, and involve biological, psychological and social factors [22]. These complex conditions often require multidisciplinary interventions for a successful RTW.

In Norway, occupational rehabilitation is established as out-patient or residence rehabilitation programmes. A residence programme will focus on individual and work-place related factors to enhance RTW. The interventions focus on diminishing the limitations identified during the assessment, building self-confidence and training in stress management. Cognitive approaches like awareness, coping strategies [23] and increased mindfulness [21, 24], as well as physical activities, are found to enhance RTW in individuals with musculoskeletal or psychological problems [25, 26]. Studies also show that brief interventions including a thorough medical examination, providing explanations of the patient’s complaints and encouragement to stay active have been of importance for a successful RTW [27, 28].

Long-term disability is no longer seen simply as the consequence of an illness/impairment, but rather as the result of interactions between the worker, the health care system, work environment and the financial compensation systems [29]. MacEachen et al. [30] found that return to work extends beyond concerns about managing physical function to the complexities related to beliefs, roles, and perceptions of many stakeholders. RTW after long term sick leave can be viewed as a complex behavioural change which involves recovery of function, motivation, behaviour and interaction with several stakeholders [31].

Occupational rehabilitation is aiming to facilitate learning and changing processes and enhance awareness of own resources and possibilities that contributes to restoring or keeping work ability. However, we have limited knowledge about what specific elements the patients perceive as crucial in the RTW processes. The aim of our study was to explore individual experiences regarding important elements of the rehabilitation programme that might have contributed to a successful RTW 3 years after completing the programme. Such knowledge may contribute to increased quality of the occupational rehabilitation processes.

Materials and Methods

The study was based on qualitative interviews of 20 individuals who attended an occupational rehabilitation programme 3 years earlier. At inclusion, the patients were on long-term sick leave due to musculoskeletal and/or psychological health complaints. They were all assessed as having a rehabilitation potential with a fair chance of being able to RTW before entering the programme. The occupational rehabilitation programme was a 4 weeks, 7 h a day group based programme led by an interdisciplinary team (physicians, nurses, physical activity instructors, physiotherapists and work-place counsellors). The participants were admitted in groups. The rehabilitation programme included different physical activities and individual and group based counselling aiming to increase function and work related processes.

Data Collection

An invitation letter was distributed to patients who had completed the occupational rehabilitation programme in 2004 (n = 632) and who participated in a cross sectional survey 3 years later. A total of 358 individuals (57%) returned the questionnaire and a written consent. In order to obtain sufficient information about factors that might have facilitated a RTW, we invited 10 individuals who had returned to work (three men 46–58 years old, seven women 41–56 years old) and 10 individuals registered with a disability pension (three men 41–53 years old, seven women 41–56 years old) to participate in a semi-structured telephone interview (Table 1). The interviews were audio taped, and lasted for 30–60 min and were conducted by either of the authors. An interview guide with open-ended questions had been developed and addressed experiences with the rehabilitation programme. The participants were asked to draw attention to both positive and negative experiences (Table 2). The main objective of the interview was to make it possible for each participant to report their individual experiences of what part of the programme they assessed as most crucial in the RTW process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants being interviewed

| Sex | Age | Work status |

|---|---|---|

| Disability pension (DP) | ||

| Full time work (FTW) | ||

| Part time work (PTW) | ||

| M | 53 | DP |

| M | 46 | DP |

| M | 41 | DP |

| F | 56 | DP |

| F | 49 | DP |

| F | 41 | DP |

| F | 42 | DP |

| F | 43 | DP |

| F | 56 | DP |

| F | 51 | DP |

| M | 46 | FTW |

| M | 58 | FTW |

| M | 55 | PTW |

| F | 48 | PTW |

| F | 56 | FTW |

| F | 41 | FTW |

| F | 56 | FTW |

| F | 53 | FTW |

| F | 43 | FTW |

| F | 48 | FTW |

Table 2.

Semi-structured interview guide

| 1. | Tell me about your situation today in relation to work and other activities? |

| 2. | Do you remember what your expectations to your rehabilitation stay were? |

| 3. | In what way were your expectations met? |

| 4. | What during the stay was of special importance for you? |

| 5. | Are there any special moments or situations you remember especially? |

| 6. | If there was something you experienced during the rehabilitation stay that promoted your return to work—what would that have been? |

| 7. | If there was something you missed during the stay, what would that have been? |

| 8. | What happened afterwards? |

| 9. | What do you think have facilitated your return to work (been barriers)? |

| 10. | How would you describe your work ability today? |

| 11. | Do you have any idea what promotes your work ability? |

| 12. | Something you think I should have asked you about? |

Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed by systematic text condensation inspired by Giorgi’s phenomenological analysis through the following four stages: (a) reading all the material to obtain an overall impression; (b) identify units of meaning, representing different aspects of the participants’ experiences regarding the rehabilitation programme; (c) condensing and summarising the contents of each of the individual meaning units and (d) summarising the contents of each meaning unit to generalise descriptions and concepts regarding their experiences [32, 33].

Ethical Considerations

The respondents were informed of the purpose of the interview, that participation was voluntary and that they were free to end the interview at any time. They gave their permission for the interview to be audio taped and were assured of confidentiality and that data would be securely stored. The ethical regional board approved the study.

Results

The analysis showed that the participants did not distinguish between what was important regarding work and what was important regarding their family and life situation in general. They talked about their total life situation when they reported what had been of importance for the outcome of the rehabilitation. Both the participants who had returned to work and the participants on disability pension (DP) emphasized the totality of the rehabilitation programme. Contributing factors identified by all participants were; physical activity in groups, social activities, leisure time, and individual and group based counselling with the professional team members.

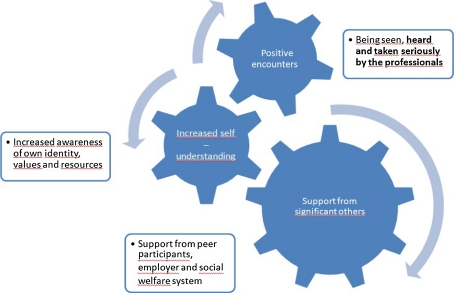

Further analysis, into what aspects of the stay at the rehabilitation clinic that contributed to return to work it became clear that the informants represented two different groups. These groups clearly split the informants into those who had successfully returned to work and those who had been granted DP after the rehabilitation. While disability pensioners emphasized to be seen, heard and taken seriously by the professionals, the informants who had returned to work regarded opportunities for increased self-understanding as important. All informants emphasised the importance of support from peer participants, family, employer or social welfare officers during the RTW process. The factors influencing a successful RTW process may be sorted under three core categories: positive encounters, increased self-understanding and support from the surroundings.

Positive Encounters

The disability pensioners underlined the importance of being seen, heard and taken seriously by the health professionals at the rehabilitation clinic. Many of them described earlier experiences regarding encounters with health professionals, social security and/or employers. They often felt misunderstood and distrusted. To be taken seriously implied that the professionals believed in their description of complaints and that a useful somatic diagnosis was given. They wanted the health personnel to give support and acknowledge their complaints and efforts in life. One woman expressed it like this:

“…it is real (my complaints). I am not tired or lazy. It just feels good in a way to be believed in.”

Increased Self-Understanding

The participants in the RTW group regarded the opportunity for increased self understanding as paramount and this was not mentioned by the DP group. Increased self-understanding implied increased awareness of own identity, values, resources and opportunity to act differently. They expressed the value of the programme as the balance between the opportunity to be physically active and being challenged on self-reflection. Testing their physical capacity in a safe environment with professional health care workers available was underlined as an important aspect to get to know oneself better. This enabled the participants to trust their own limits and to challenge their physical abilities. Many experienced that they managed more than they believed earlier and this gave them increased self-confidence that was transferable to their working life. To be provided enough time and concurrently being challenged on self-reflection implied that they spent time lingering with topics like identity, values and own resources.

Identity

Many of the RTW group participants expressed that being on sick leave was like losing their footing in life. Work represented an important arena for identity. They felt valuable and work represented a psychosocial well being in addition to a social network. Being on long-term sick leave implied starting to doubt this identity. They lost an important arena for social network and they started to feel uncertain and vulnerable. One woman stated:

“Who am I if I am not a teacher anymore…”

Many also expressed that identity did not seem to be permanent. One man expressed it like this:

“I understood that it was possible, I did not have to be the person I am now (a patient) for the rest of my life.”

Values: What is Important to Me

Many of the RTW group participants expressed that they spent time trying to find out what was important to them in their life and how they could prioritise to manage both family, work and leisure time. Many realized that they had not lived a life in accordance with their own values and had perhaps underestimated their own needs. One woman said:

“I learned to give priority to what I wanted – what was of importance to me. I made a list of priorities - what I spent my time doing and what was important for me to do”

The RTW group participants expressed that the rehabilitation programme had encouraged them to reflect on what was important to them, and they realized that they had a choice in life. They increased their awareness of living in accordance with own values. Many of them had experienced being trapped in their own thoughts, and the programme stimulated them to make new reflections regarding own values. This gave them increased awareness of own will and own choice rather than doing what they thought other people expected them to do. One woman expressed it like this:

“I sat down to double check my goals in life. Is it necessary? Who am I doing it for? What do I accomplish? And what will be required of me to do it?”

By self-reflection they started a changing process that resulted in increased awareness of how to live in accordance with own values. Many of the RTW participants also described that they reduced their own work demands. One man in his fifties put it this way:

“I had to learn about mechanisms in myself that promoted my burned-out situation. I was very proud; I pressed myself to achieve good results, very difficult for me not to succeed in everything I do. I had to understand this about myself. I now have a more relaxed attitude; I feel safer within myself… I have learned to know my body, to listen to it – so I don’t work like a dog any more, I do not exploit myself ruthlessly”

Own Resources

Increased self-awareness also facilitated a change in thoughts about own health situation. The RTW participants realized that they could continue to focus on illness and health limitations, or they could choose to focus on own resources and possibilities. Their choice affected the level of energy they experienced and the direction they wanted to take. A woman expressed it like this:

“The fact that there are things that I can do and that focus should not be on what I can’t do. Even if I wanted to I couldn’t return to my job as an aircraft mechanic. So I could sit down and be depressed, or I could choose to focus on everything I actually can do. My focus has been on finding things I can do and not grieve over what I cannot do.”

On the other side, the DP group participants expressed the view that their illness was outside their own control, and that they had to get well before even thinking of working. Irrespective of own behaviour and attitudes, the disability pensioners had a strong focus on diagnosis and illness and the need of a specific treatment to get well. They felt helpless; no matter what they did, the pain was still there, and the pain had to be relieved before even thinking of RTW. They regarded themselves more as passive pawns than in charge of their own situation.

Support from the Surroundings

All participants emphasised the importance of support from peer participants at the rehabilitation clinic, family, employer or social welfare officers during the RTW process.

Belonging to a Group

At the clinic the inpatients were divided into groups, and counselling and training were provided both individually and in groups. Belonging to a group was stated to be of great importance, both the formally organized groups and self-organized groups. Listening to other peoples stories made them able to draw parallels to their own life and in this way increase their own understanding. Discovering that other people were in the same situation and they were not alone with their experiences, enhanced a feeling of companionship and security. Many of the participants had interpreted their situation or complaints as very special, and as a sign of their specific illness. Discovering that other people were in a similar situation or had similar experiences contributed to normalization of their own situation. To be able to share their story gave them a broader perspective on their own situation and a feeling of not being alone. Sharing of stories with other inpatients made them also realize that they were useful for other people and they could challenge each other and learn from each other’s experiences. Different aspects of belonging to a group appeared during the interviews. The participants who had returned to work emphasized being each other’s sparring partners and this facilitated their own reflections and self-understanding. One man expressed it like this:

“I tried to look into myself seriously, and I was challenged by the others, especially by the other participants. So adding up the counselling (by the professionals) and the input from the other participants was a very good coaching situation for me.”

Views on this differed as the DP group participants emphasized to a larger degree the social aspects of the group and the feeling of being in the same boat. Group membership also helped the participants to feel confident together with other people and dare talking about difficult aspects of life. Many had been isolated during their sick leave period and had experienced difficulties in talking to people or take initiative to be together. Coping with the social companionship in the group gave them increased confidence with regard to the social companionship at work.

Negative experiences with the group sessions also appeared. Some of the participants in the DP group experienced the counselling group meetings as too challenging and demanding, and they experienced the meetings as a personal defeat. For them it was difficult to be in a group with people that were motivated for RTW and therefore received support from the professional team. This reinforced negative feelings within themselves, and they felt like losers.

Support from the Employer

Some RTW participants underlined that support from the employer contributed to a successful RTW, while lack of support could have the opposite effect. Changing own behaviour and thinking was the most important factor, but support and adjustments at the workplace was also mentioned as a prerequisite for a successful RTW. One woman put it like this:

“I had a fantastic employer who paved the way for my return. He asked me if I could do this or that. They were fantastic at the workplace. They put so much effort in keeping me so I got a lot of confidence – when they take the chance I have to do my bit.”

Discussion and Conclusions

This study indicates that learning processes allowing increased self-understanding were essential elements in the RTW process. The study shows that the two groups (RTW and DP) valued different aspects of the rehabilitation programme. The DP group valued positive encounters with the professionals per se, while the RTW group additionally valued the opportunity to reflect on topics like self-understanding. Positive encounters included being seen, heard and taken seriously by the professional team, and were described as a prerequisite for the learning processes (changes) to happen. Increased self-understanding implied increased awareness of own identity, values and resources. In addition, success in the RTW process seemed to presuppose support from significant others like peer participants, the employer and the social welfare system (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Valued elements of the return to work process as perceived by the participants in the occupational rehabilitation program

Increased Self-Understanding

In this study, a central issue for a successful RTW process was increased self-understanding. The participants expressed that during the rehabilitation stay they had experienced a possibility for reconstruction of self. The participants who had re-entered work, emphasized the experience of increased awareness of own identity, values and resources as an important step towards work. They regarded themselves as competent and able to take control over own life situation and thereby control over the rehabilitation process. They focused on how they could manage everyday life despite pain rather than on pain relief and cause of illness. The rehabilitation programme helped them realize their own influence on the RTW processes. On the other hand, participants who had become disability pensioners externalised their problems and stated a view that the treatment outcome had been more dependent on external circumstances like the competence of the professional team or lack of support from employer. They focused on pain relief and expected passive treatment modalities to alleviate their pain, and getting well before returning to work.

Nygård [34] points out that a central issue when trying to understand our ways of handling the varied situations with which we are confronted, is how we interpret and construct ourselves i.e. what kind of understanding of self we bring to these situations. He emphasizes whether a person tends to construct himself or herself as an origin of behaviour—an agent—an inner-directed person or as a pawn—an outer-directed person who experience that there are someone or something outside who is in charge of control. Persons who for a long time have viewed themselves as pawns may find it challenging to change their role to a more agent—oriented person. Our findings are in accordance with Nygårds theories on agent-orientation [34]. Participants who had re-entered work after rehabilitation focused on how to live in accordance with own values and resources in spite of their pain and problems, they had control over own life situation, while the disability pensioners expressed that success after the rehabilitation was dependent on external factors like the team, the employer or pain relief. This creates a difference in the purpose for which treatment strategies are implemented. Explicit goal of pain reduction or improved pain management might be substituted by methods enhancing self understanding. This is in accordance with what Mc Cracken et al. [35] found in rehabilitation of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Rehabilitation and RTW processes are described as taking control over everyday life, or as a desire and capacity to take charge of their life situation [36, 37]. Fjellman-Wiklund et al. [38] describes rehabilitation as a process where the “getting to know myself” and “how can I be the one I want to be” are basic conditions for a successful RTW. This study indicates that the way I comprehend myself can be reconstructed, and this is important in developing new strategies to handle life situation and the RTW processes.

Our self understanding might be decisive for our health and how we cope with illness and challenges in everyday life. The question is whether the individual perceives himself as an agent (internalising) or as a pawn (externalising).

The shift from surrendering the authority about their pain to health professionals to search for and find both authority and answers in themselves is a major shift in understanding. The participants told that active participation and time had been necessary for understanding and feeling comfortable to make this shift. They needed to experience and be assured that they had the answers within themselves. Being told by others was not enough. This demonstrates the importance of experience oriented learning when entering a process in order to change beliefs, behaviour and attitudes.

The participants acknowledged the group as an arena for learning. The social setting was an arena for practising new behaviour and recognition of own thoughts and emotions. The experience of “being in the same boat” contributed to normalization of symptoms and pain. This is in accordance with other studies that have found that group support seems to strengthen the empowerment and enhance the reconstruction of identity by providing opportunities for self-evaluation and comparison [39, 40].

Positive Encounters

Several of the participants had previously experienced distrust from health personnel and this had led to reduced self-confidence, a feeling of hopelessness and loss of work ability. Stories were told about being stigmatised and not taken seriously by health personnel. The rehabilitation team had legitimated and acknowledged their pain and problems and their social status as a person on sick leave. The impact of positive interaction with professionals regarding RTW has been underscored in previous studies [41, 42]. Svensson et al. [42] found that when persons on sick leave were asked about factors that hindered or promoted RTW in general, they indicated positive and negative encounters with healthcare and social insurance professionals as decisive. Examples of positive experiences comprised being believed, taken seriously and considered to be in the right, feeling that the professionals listened, that they were supportive and/or encouraging, and showed personal involvement and confidence in the person’s ability to work [42]. This is in line with our findings. However, in our study experiencing positive encounters without being challenged enough on own self-understanding and without enough support from significant others may seem to increase the risk of disability.

Support from Significant Others

The experience of change in self-understanding and a successful RTW as described by the participants occurred as a result of self-reflection that led to increased awareness of own identity, values and resources. This process was not linear, but individual and complex, and was also related to interactions with significant others (like peer participants, employer, social welfare office etc.). The participants emphasized the employers’ belief in their capacity and resources and this facilitated the RTW process. Other studies also emphasize the importance of perceived social support in the RTW process [43, 44]. In this study the employers’ capacity and will to reorganize the workplace for the employees seems to be important but not sufficient for a successful RTW.

Methodological Considerations

In this study we have back ground information of the participants’ gender, age and work status. Knowledge about education and previous employment might have been beneficial in the interpretation of our results. Studies have shown that socio-economic status like education and income may be important predictors for RTW [16, 45]. The participants who succeeded in returning to work might have had a higher education and possibly also higher capability of increasing own self-understanding. Our study indicated furthermore that the participants who did not succeed in RTW had a higher focus on biomedical causes of their illness and experienced less control of their own situation. This may also be explained by the individual’s level socio-economic status. The participants were asked about their experiences 3–4 years after their rehabilitation stay. The time factor may represent a recall bias in what was of most importance for their RTW process. The participants might also have had a recall bias remembering what could justify their own situation. None of the authors were involved in the rehabilitation of the participants, but LH presently holds a position at the rehabilitation center. The author’s interest and knowledge in the field will however have influenced the questions and dialogue in the semi-structured interviews and the analysis.

Conclusions

Successful RTW processes seem to comprise positive encounters, an opportunity for increased self-understanding and support from the surroundings. Explicit focuses on topics like identity, values and own resources might improve the outcome of the rehabilitation process. Use of a group setting also seems to be of relevance. This study indicates that medical knowledge alone is not sufficient to help people to return to work. Health professionals working with these patients probably need specific education and training in educational methods to counsel patients to increased self-understanding.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Blank L, Peters J, Pickvance S, Wilford J, Macdonald E. A systematic review of the factors which predict return to work for people suffering episodes of poor mental health. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuijer W, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU. Prediction of sickness absence in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(3):439–467. doi: 10.1007/s10926-006-9021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagerveld SE, Bultmann U, Franche RL, van Dijk FJ, Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, et al. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):275–292. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelius LR, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S. Prognostic factors of long term disability due to mental disorders: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010 [Nov 6, Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dekkers-Sanchez PM, Hoving JL, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Factors associated with long-term sick leave in sick-listed employees: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(3):153–157. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.034983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young AE, Roessler RT, Wasiak R, McPherson KM, van Poppel MN, Anema JR. A developmental conceptualization of return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):557–568. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-8034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw W, Hong QN, Pransky G, Loisel P. A literature review describing the role of return-to-work coordinators in trial programs and interventions designed to prevent workplace disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(1):2–15. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, Meloche GR, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, et al. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(23):2720–2725. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A. Rehabilitation and work ability: a systematic literature review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(10):796–804. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, Cameron J, Hillage J. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(8):607–621. doi: 10.3109/09638280903186301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norlund A, Ropponen A, Alexanderson K. Multidisciplinary interventions: review of studies of return to work after rehabilitation for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(3):115–121. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loisel P, Durand MJ, Diallo B, Vachon B, Charpentier N, Labelle J. From evidence to community practice in work rehabilitation: the Quebec experience. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(2):105–113. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norwegian labour and welfare service. Nav. Tall og analyser fra Nav. http://www.nav.no/Om+NAV/Tall+og+analyse/Jobb+og+helse. 2010.

- 14.Von Korff M, Crane P, Lane M, Miglioretti DL, Simon G, Saunders K, et al. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113(3):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagen EM, Svensen E, Eriksen HR, Ihlebaek CM, Ursin H. Comorbid subjective health complaints in low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(13):1491–1495. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219947.71168.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyeflaten I, Hysing M, Eriksen HR. Prognostic factors associated with return to work following multidisciplinary vocational rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(7):548–554. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, Bruusgaard D. Does the number of musculoskeletal pain sites predict work disability? A 14-year prospective study. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(4):426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagen EM, Svensen E, Eriksen HR. Predictors and modifiers of treatment effect influencing sick leave in subacute low back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(24):2717–2723. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000190394.05359.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagen KB, Tambs K, Bjerkedal T. A prospective cohort study of risk factors for disability retirement because of back pain in the general working population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(16):1790–1796. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haldorsen EM, Kronholm K, Skouen JS, Ursin H. Predictors for outcome of a multi-modal cognitive behavioural treatment program for low back pain patients-a 12-month follow-up study. Eur J Pain. 1998;2(4):293–307. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(98)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haugli L, Steen E, Lærum E, Nygård R, Finset A. Psychological distress and employment status in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Results from a group learning programme as an occupational rehabilitation approach. Psychol Health Med. 2003;8(2):135–148. doi: 10.1080/1354850031000087519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell G, Burton AK. Concepts of rehabilitation for the management of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(4):655–670. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grahn B, Stigmar K, Ekdahl C. Motivation for change in patients with prolonged musculoskeletal disorders: a qualitative two-year follow-up study. Physiother Res Int. 1999;4(3):170–189. doi: 10.1002/pri.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahl J, Wilson KG, Nilsson A. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the treatment of persons at risk for long-term disability resulting from stress and pain symptoms: a preliminary randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2004;35:785–801. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80020-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Martinsen EW. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(Suppl 47):25–29. doi: 10.1080/08039480802315640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(4):473–477. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagen EM, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(15):1973–1976. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franche RL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1020270407044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):257–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young AE, Wasiak R, Roessler RT, McPherson KM, Anema JR, van Poppel MN. Return-to-work outcomes following work disability: stakeholder motivations, interests and concerns. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):543–556. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-8033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giorgi A. Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. In: Giorgi A, editor. Phenomenology in psychological research. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 1985. pp. 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nygård R. Agent or pawn. About peoples self-understanding. In: Norwegian: Aktør eller brikke. Om menneskers selvforståelse. Oslo: Ad Notam, Gyldendal; 1993.

- 35.McCracken LM, Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Vowles KE. The role of mindfulness in a contextual cognitive-behavioral analysis of chronic pain-related suffering and disability. Pain. 2007;131(1–2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eriksson T, Karlstrom E, Jonsson H, Tham K. An exploratory study of the rehabilitation process of people with stress-related disorders. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(1):29–39. doi: 10.3109/11038120902956878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bullington J, Nordemar R, Nordemar K, Sjostrom-Flanagan C. Meaning out of chaos: a way to understand chronic pain. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17(4):325–331. doi: 10.1046/j.0283-9318.2003.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fjellman-Wiklund A, Stenlund T, Steinholtz K, Ahlgren C. Take charge: patients’ experiences during participation in a rehabilitation programme for burnout. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(5):475–481. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA. Participation in online patient support groups endorses patients’ empowerment. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez-Martinez AE, Esteve-Zarazaga R, Ramirez-Maestre C. Perceived social support and coping responses are independent variables explaining pain adjustment among chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2008;9(4):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svensson T, Karlsson A, Nordquist C, Alexanderson K. Shame induced encounters-negative emotional aspects of sick-abesentees’ interaction with rehabilitation professionals. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(3):183–195. doi: 10.1023/A:1024905302323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klanghed U, Svensson T, Alexanderson K. Positive encounters with rehabilitation professionals reported by persons with experience of sickness absence. Work. 2004;22(3):247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lysaght RM, Larmour-Trode S. An exploration of social support as a factor in the return-to-work process. Work. 2008;30(3):255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brouwer S, Reneman MF, Bultmann U, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW. A prospective study of return to work across health conditions: perceived work attitude, self-efficacy and perceived social support. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):104–112. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9214-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kristenson M, Eriksen HR, Sluiter JK, Starke D, Ursin H. Psychobiological mechanisms of socioeconomic differences in health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(8):1511–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]