Abstract

Background Research on disability and RTW outcome has led to significant advances in understanding these outcomes, however, limited studies focus on measuring the RTW process. After a prolonged period of sickness absence, the assessment of the RTW process by investigating RTW Effort Sufficiency (RTW-ES) is essential. However, little is known about factors influencing RTW-ES. Also, the correspondence in factors determining RTW-ES and RTW is unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate 1) the strength and relevance of factors related to RTW-ES and RTW (no/partial RTW), and 2) the comparability of factors associated with RTW-ES and with RTW. Methods During 4 months, all assessments of RTW-ES and RTW (no/partial RTW) among employees applying for disability benefits after 2 years of sickness absence, performed by labor experts at 3 Dutch Social Insurance Institute locations, were investigated by means of a questionnaire. Results Questionnaires concerning 415 cases were available. Using multiple logistic regression analysis, the only factor related to RTW-ES is a good employer-employee relationship. Factors related to RTW (no/partial RTW) were found to be high education, no previous periods of complete disability and a good employer-employee relationship. Conclusions Different factors are relevant to RTW-ES and RTW, but the employer-employee relationship is relevant for both. Considering the importance of the assessment of RTW-ES after a prolonged period of sickness absence among employees who are not fully disabled, this knowledge is essential for the assessment of RTW-ES and the RTW process itself.

Keywords: Return-to-work, Vocational Rehabilitation, Disability Insurance, Outcome measures, Employer effort

Background

In the past years, policymakers and researchers have focused on early return-to-work (RTW) after sickness absence and on the prevention of long-term sickness absence and permanent disability [1, 2]. Long-term absence and work disability are associated with health risks, social isolation and exclusion from the labor market [1, 2]. Although research on disability and RTW outcome has led to significant advances in understanding about these outcomes, limited studies focus on measuring aspects of the RTW process—the process that workers go through to reach, or attempt to reach, their goals [3]. Up to date, the focus is commonly placed on simply the act of returning-to-work or applying for a disability pension. However, RTW and work disability can also be described in terms of the type of actions undertaken by workers resuming employment [4].

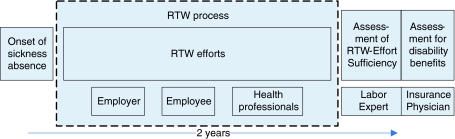

An instrument to measure the undertaken actions in the RTW process and to evaluate if an agreed upon RTW goal has been reached is of interest of various stakeholders. In several countries the assessment of Return-To-Work Effort Sufficiency (RTW-ES) is part of the evaluation of the RTW process in relation to the application for disability benefits [5]. After the onset of sickness absence, the RTW process takes place. RTW efforts made in the RTW process include all activities undertaken to improve the work ability of the sick-listed employee in the period between onset of sickness absence and the application for disability benefits (see Fig. 1) [6]. During this RTW process, the RTW efforts are undertaken by employer, employee, and health professionals (e.g. general physician, specialist, and/or occupational physician). The assessment of RTW-ES explores the RTW process from the perspective of the efforts made by both employer and employee. This assessment takes place prior to the assessment of disability benefits, which in the Netherlands takes place after 2 years of sickness absence [6]. The assessment of RTW-ES and the assessment for disability benefits are performed by the Labor Expert (LE) and a Social Insurance Physician (SIP), respectively, of the Social Insurance Institute (SII).

Fig. 1.

A description of the RTW process in relation to the assessment of Return-To-Work Effort Sufficiency and the assessment for disability benefits

The RTW efforts are sufficient if the RTW process is designed effectively, the chances of RTW are optimal, and RTW is achieved in accordance with health status and work ability of the sick-listed employee [5, 7]. The RTW-ES assessment is performed only when the Dutch employee has not fully returned to work after 2 years of sickness absence, but does have remaining work ability and is applying for disability benefits. Of employees applying for disability benefits, some apply for partial benefits, and some apply for complete benefits, based mainly on the level of RTW achieved during the RTW process, i.e. no RTW or partial RTW. Little is known about the differences between employees who apply for disability benefits after long-term sickness absence who have achieved partial RTW and those who have not achieved RTW.

Assessing the sufficiency of the efforts made during the RTW process prior to the application for disability benefits could help prevent unnecessary applications for disability benefits. However, current RTW process outcomes focus mostly on time elapsed or costs [4], and not on the RTW process. Assessing the sufficiency of efforts undertaken during the RTW process might be an important addition to existing RTW outcomes as it could give insight in factors related to RTW in employees on long-term sickness absence who apply for disability benefits [5].

Because the RTW outcome is assessed after a longer period of sickness absence, the influence of the activities undertaken in the RTW process is evident. Knowing the strength and relevance of factors influencing the RTW process can provide vital information for the RTW outcome and the opportunities to achieve better RTW goals in the future. Ultimately, knowing the differences in factors associated to RTW-ES among employees who have not returned to work fully, but do have remaining work ability, might give insight in the differences between factors related to RTW outcome and the factors during the RTW process related to the assessment of RTW-ES. Moreover, the comparability of both outcomes (RTW outcome versus RTW-ES outcome) is unclear. Factors related to RTW among employees on long-term sickness absence and applying for disability benefits might differ from factors relevant to the RTW-ES outcome measured by the activities during the RTW process.

The purpose of this study was to investigate 1) the strength and relevance of factors related to RTW Effort Sufficiency (RTW-ES) and to RTW outcome (no RTW or partial RTW) among employees applying for disability benefits after 2 years of sickness absence, and 2) the comparability of the factors associated with RTW-ES and RTW.

Methods

Measures

RTW-ES Assessment

The RTW-ES assessment focuses on whether enough activities have been undertaken by the employer and employee to realize (partial) RTW after 2 years of sickness absence. This assessment is based on a case report compiled by the employer. This case report includes a problem analysis, i.e. a mandatory description of the (dis)abilities of the employee by an occupational physician hired by the employer, the plan designed to achieve work resumption (an action plan), and the employee’s opinion regarding the RTW process. Records of all interventions, conversations and agreements between the parties involved in the RTW process were also included in the case report. The assessment is performed by LE’s from the Dutch SII, who are graduates in social sciences. During the assessment, the LE’s have the opportunity to consult an SIP, and can invite the employer and employee to provide more information. When, according to the LE insufficient efforts have been made, the application for disability benefits is delayed, and the employer and/or employee receive a financial sanction, depending on who has omitted to perform the necessary efforts to promote RTW. The assessment of RTW-ES is performed at the disgression of the LE’s, no evidence based protocol or instrument is available. Employees who have returned to work fully and are receiving the original level of income, or who are fully disabled are not assessed. Employees on sickness absence due to pregnancy, or on sickness absence while not under contract fall under a different policy and are not assessed as well.

Research Questionnaire

A closed-ended questionnaire was developed to gather information about the two outcomes, RTW and RTW-ES, and personal and external factors related to the case and the RTW process of the employee.

The strength and relevance of factors related to RTW-ES and to RTW outcome (no RTW or partial RTW) were investigated by means of a questionnaire. During the RTW-ES assessment, the LE was asked to fill out the questionnaire.

The content of the questionnaire consists of a list of possible predicting factors of RTW, which were inventorized by literature (e.g. [8–10]). Questions were included about personal factors such as age, gender, level of education (low, medium, high, including examples), and more work-related personal factors such as the reason of sickness absence (i.e. physical, mental or both) and tenure (number of years with current employer). Questions about whether there had been periods of work resumption (yes, no) or periods of complete disability (yes, no) were also included. For the external factors questions were asked about whether the sickness absence was work-related (yes, both work-related and private, no), whether there had been a conflict between the employer and employee during the RTW process (yes, no), and also whether the quality of the relationship between the employer and employee was deemed good/neutral or bad. A question about whether the employee had returned to work (yes/no) was included, as well as a question about the sufficiency of RTW efforts (sufficient/insufficient) according to the LE. The LE’s gathered the information necessary for filling out the questionnaire by examining the case report or interviewing the employer, employee or SIP.

Statistical Analyses

Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent contribution of factors to the RTW outcome. The method used was backward conditional, because of the explorative nature of the analyses.

Similar to the analyses of RTW, multilevel regression analysis was used to analyze the relationship between the factors and the RTW process outcome in terms of sufficiency of RTW efforts, taking the assessing professional into account. In both multiple analyses, variables were entered in the model when P < 0.20 based on the univariate relationships, and were adjusted for age, gender and education level. Data analysis was performed by using SPSS 16.0 for MS Windows.

Comparability

The results of the statistical analyses were used to assess the comparability of the factors associated with RTW-ES and RTW.

Results

Study Population

Questionnaires concerning 415 cases were filled out.

Of all cases, the average age of the employees was 47 years (SD 9.4), 180 (43%) were male, and education level was low in 20%, medium in 60% and high in 20% (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of study population

| Age M(SD) (N = 415) | 47.4 (9.4) |

| Gender N(%) (N = 415) | |

| Male | 180 (43.4) |

| Female | 235 (56.6) |

| Educational level N(%) (N = 410) | |

| Low | 84 (20.5) |

| Medium | 246 (60.0) |

| High | 80 (19.5) |

| RTW N(%) (N = 411) | |

| No (or only on a therapeutic basis) | 211 (51.3) |

| Yes (partially or fully) | 200 (48.7) |

| RTW efforts N (%) (N = 415) | |

| Sufficient | 334 (80.5) |

| Insufficient | 81 (19.5) |

| RTW at own employer (N = 196) | |

| Yes | 191 (97.4) |

| No | 5 (2.6) |

| RTW process agreed on by employee (N = 409) | |

| Yes | 329 (80.4) |

| No | 80 (19.6) |

Of the 415 cases, RTW-ES was deemed sufficient in 334 cases (80%) and insufficient in 81 cases (20%). Of the 415 cases, 203 sick-listed employees had returned to work partially prior to applying for disability benefits, whereas 211 sick-listed employees (51%) had not returned to work.

At the moment of application for disability benefits, 191 employees who had returned to work had returned to their own employer (97%), whereas 5 had not (3%). The RTW process was agreed upon by the employee in 329 cases (80%), while 80 employees (20%) did not agree with the proceedings of the 2 years prior to the application for disability benefits.

Personal and External Characteristics

The characteristics of the variables included in the logistic analyses are presented in Table 2. Regarding the personal factors, the reason of absence was a physical health condition in 261 cases (63%), mixed health conditions in 67 cases (16%), and a mental health condition in 84 cases (20%). The average tenure was 13 years (SD 8.8). Of the sick-listed employees, 272 (66%) reported periods of complete disability, which meant that no activities to promote RTW could be undertaken during this period. 218 employees (53%) reported periods of work resumption, meaning that they had attempted to RTW during the 2 years before the application for disability benefits.

Table 2.

Description of personal and external factors in study population

| Personal factors | N (%) |

| Reason of absence (N = 412) | |

| Physical | 261 (63.3) |

| Both physical and mental | 67 (16.3) |

| Mental | 84 (20.4) |

| Tenure (N = 358) (M(SD)) | 12.84 (8.75) |

| Periods of complete disability (N = 412) | |

| Yes | 272 (66.0) |

| No | 140 (34.0) |

| Periods of work resumption (N = 412) | |

| Yes | 218 (52.9) |

| No | 194 (47.1) |

| External factors | N (%) |

| Sickness absence work related (N = 339) | |

| Yes, completely/partially | 55 (16.2) |

| No | 284 (83.8) |

| Relationship employer employee (N = 380) | |

| Good/neutral | 355 (93.4) |

| Bad | 25 (6.6) |

| Conflict (N = 410) | |

| Yes | 32 (7.8) |

| No | 378 (92.2) |

For the external factors, the sickness absence was partially or completely work-related in 55 cases (16%). The relationship between the employer and employee was good or neutral in 355 cases (93%). There was evidence of conflict between employer and employee in 32 cases (8%). The correlation between employer-employee relationship and employer-employee conflict was 0.72 (P < 0.01).

RTW-ES and RTW

Factors related to RTW-ES are shown in Table 3. The multilevel regression analysis shows 5 potential determinants (P < 0.20) of RTW-ES, while taking assessor into account: reason of absence, tenure, work-relatedness of absence, employer-employee relationship, and employer-employee conflict.

Table 3.

Factors related to RTW-ES: multilevel logistic regression analyses, taking assessor into account

| Variable (reference group) | Crude odds ratios | OR, adjusted for age, gender, and educationª | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%) | P | OR (95%) | P | |

| Personal factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.93 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.65 |

| Gender (female) | 1.07 (0.68–1.71) | 0.76 | 0.97 (0.51–1.85) | 0.92 |

| Education (low) | 1.02 (0.43–2.41) | 0.97 | 1.08 (0.35–3.32) | 0.89 |

| Reason of absence (mental)¹ | 1.97 (1.14–3.42) | 0.02 | 1.22 (0.57–2.61) | 0.60 |

| Tenure (years) | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.14 | 1.03 (0.98–1.01) | 0.23 |

| Periods of complete disability (no) | 1.19 (0.75–1.89) | 0.45 | – | – |

| Periods of work resumption (no) | 1.22 (0.76–1.95) | 0.42 | – | – |

| External factors | ||||

| Sickness absence work related (yes)² | 2.73 (1.33–5.62) | 0.01 | 1.44 (0.64–3.22) | 0.38 |

| Relationship employer/employee (poor) | 5.91 (2.81–12.43) | <0.01 | 5.47 (2.00–14.98) | <0.01 |

| Conflict (yes)³ | 4.25 (2.14–8.43) | <0.01 | – | |

OR of >1 indicates a higher chance of RTW-ES, compared to the reference group

ª QIC = 265.92, N = 269

1Physical, both physical and mental, mental

2No, partial/yes

3r = 0.72 with variable ‘relationship employer/employee’; not included in multiple regression

Using multiple multilevel logistic regression analysis, adjusting for age, gender and education and excluding conflict, one factor remained in the model. Only employer-employee relationship had a significant relationship to a higher chance of RTW-ES (OR 5.47, 95%CI 2.00-14.98, P < 0.01).

Factors related to RTW according to the regression analysis are presented in Table 4. In the univariate regression analyses 5 potential determinants were associated (P < 0.20) to RTW: education level, tenure, periods of complete disability, relationship between employer and employee, and employer-employee conflict. Conflict was excluded from the model because of the high correlation to employer-employee relationship, and the model was adjusted for age, gender and education. Using multiple backward conditional logistic regression analysis, three factors remained in the model: employer-employee relationship (OR 14.59, 95%CI 3.29-64.71, P = <0.01), level of education (OR 2.89, 95%CI 1.39-6.00, P = <0.01), and periods of complete disability (OR 1.92, 95%CI 1.18-3.15, P = <0.01).

Table 4.

Factors related to RTW: logistic regression analyses

| Variable (reference group) | Crude odds ratios | OR, adjusted for age, gender and educationª | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%) | P | OR (95%) | P | |

| Personal factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.98–0.02) | 0.97 | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | 0.68 |

| Gender (male) | 1.01 (0.68–1.49) | 0.97 | 0.98 (0.62–1.53) | 0.92 |

| Education (low) | 1.99 (1.07–3.70) | 0.03 | 2.89 (1.39–6.00) | <0.01 |

| Reason of absence (mental)¹ | 1.08 (0.57–2.07) | 0.81 | – | – |

| Tenure (years) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.18 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.47 |

| Periods of complete disability (yes) | 1.74 (1.15–2.63) | 0.01 | 1.92 (1.18–3.15) | <0.01 |

| Periods of work resumption (yes) | 1.16 (0.79–1.71) | 0.45 | – | – |

| External factors | ||||

| Sickness absence work related (yes)² | 1.35 (0.75–2.41) | 0.32 | – | – |

| Relationship employer/employee (poor) | 12.95 (3.01–55.74) | <0.01 | 14.59 (3.29–64.71) | <0.01 |

| Conflict (yes)³ | 5.57 (2.10–14.78) | <0.01 | – | – |

OR of >1 indicates a higher chance of RTW, compared to the reference group

aR² = 135, N = 321

1Physical, both physical and mental, mental

2No, partial/yes

3r = 0.72 with variable ‘relationship employer/employee’; not included in multiple regression analysis

Discussion

In this study, the only factor related to RTW-ES is a good relationship between employer and employee. Factors related to RTW outcome (no RTW or partial RTW) after 2 years of sickness absence were found to be high education, no previous periods of complete disability and a good relationship between employer and employee.

Included in this study were employees applying for disability after 2 years of sickness absence, who were not permanently or fully disabled. Sickness absence duration should be taken into account because the phase-specificity of sickness absence is different after 2 years of sickness absence, and other factors are related to RTW outcome [11]. Furthermore, in this study a comparison was made between employees who had achieved some RTW, and those who did not achieve RTW. Previous studies have focused on measuring RTW earlier than after 2 years, and also a distinction was made between RTW and no RTW, regardless of work ability or application for disability benefits. This could explain differences in factors related to RTW found in previous research and the results of this study.

The results found on factors related to RTW-ES can not be compared to previous studies because of lack of research on this subject.

The relation found in this study between education and RTW is congruent with existing literature. A lower education prolongs the time to RTW [12, 13]. A poor relationship between employer and employee is found to have a negative effect on RTW [14]. Moreover, supervisor support increases the chance of RTW [6, 15, 16]. Previous research has found that age, gender and tenure are related to RTW. A higher age (>50years) prolongs the time to RTW [14, 17]. Female gender decreases the chance of RTW [17], but this evidence is not conclusive [14]. A shorter tenure prolongs the time to RTW [6, 14], and a tenure longer than one [18] or 2 years [19] increases the chance of RTW. In our sample, age, gender and tenure were not found to be related to RTW. Furthermore, in this study, no relationship was found between RTW and mental health conditions as the reason of sickness absence or the work-relatedness of the sickness absence. This is also unlike the results found in previous studies, where it has been found that mental health conditions reduce the chance of RTW [20, 21]. Also, if the sickness absence is work-related, for example due to a work-related accident, this reduces the chance to RTW [22]. Furthermore, in this study, periods of work resumption were not associated to RTW.

As far as comparability of RTW-ES and RTW outcome is concerned, only the relationship between employer and employee is a shared relevant factor. Educational level and periods of previous disability are only predictors of RTW, but not of RTW-ES. This suggests that the two outcomes have limited comparability, but also that the relationship between employer and employee could be considered a very relevant factor in cases of prolonged sickness absence.

The strength of this study lies in its subject; this study is the first to investigate determinants of RTW-ES, and to compare the findings to the RTW outcome (no RTW or partial RTW). Also, this study focuses on the comparison of no RTW to partial RTW after 2 years of sickness absence. The RTW efforts are mostly of interest when the employee still has work ability, but has not yet returned to their original work fully after a prolonged period of sickness absence.

A limitation in this study is the lack of knowledge on the level of disability of the employee. It was investigated whether there had been drastic changes, such as a period of complete disability or periods of work resumption, but the RTW outcome could not be compared to the level of disability according to the physician. However, we do know that the physicians of the OHS and the SII ensure that the assessment of RTW-ES after 2 years does not include employees who are fully disabled or who have no disability at all.

Another limitation issue lies in the measurement of the determinants. Questionnaires were developed in which a certain set of variables were investigated. A different selection could have lead to different results. However, the variables were selected by means of literature and expert meetings, and we feel we have investigated several of the most relevant factors. The questionnaire and the sources used to complete the questionnaire could be a source of response bias. As far as the outcome is concerned, the assessment of RTW-ES is performed by Dutch SII LE’s, who have had similar training [5]. To avoid assessor bias, the assessor was taken into account when analyzing RTW-ES. However, it could be that a different group (e.g. from another country) would perform the assessment in their own way, thereby including other factors. On the other hand, this study provides a great opportunity to compare these results to a different situation, as this is the first study to investigate RTW-ES and to compare it to RTW after 2 years.

The relevance of this study lies in the use of RTW-ES as RTW outcome. RTW-ES is relevant to the process, especially when investigating RTW after a longer period of time in cases where the employee is expected to be able to RTW, but not fully or in the original setting. According to the findings of this study, the relationship between employer and employee is very important to both RTW and RTW-ES. This would implicate a shift from a more physical approach or a focus on the personal factors to a work-related external factor such as the relationship between employer and employee. The importance of this factor is considerable, because effective job accommodation for employees with a chronic disability is a process in which external (i.e. social) factors are essential [23]. During the RTW process, these factors are not only of great importance, but can also be influenced, in contrast to factors such as level of education and periods of complete disability. Issues regarding the relationship can be detected by external parties such as the physician or vocational rehabilitation expert, an can be improved by mediation or counseling.

This is the first study performed to investigate the factors related to RTW-ES and to compare these to factors related to RTW. In future research this study could be replicated while changing a study characteristic to determine its influence on the study outcome. For example, a different group of professionals (e.g. from another country), or different factors could be included. Also, it would be interesting to investigate RTW and RTW-ES by comparing to full RTW. However, this could also cause difficulties in research design, as full RTW in the previous work already implies RTW-ES. Moreover, full RTW is usually achieved earlier. An alternative could be to research determinants of RTW at both 6 months and 2 years, as to be able to compare the determinants of full or partial RTW.

In conclusion, this study showed that RTW-ES is largely determined by the relationship between employer and employee. Factors related to RTW after 2 years of sickness absence are educational level, periods of complete disability and also the relationship between employer and employee. It can be concluded that RTW-ES and RTW are different outcomes, but that the relationship between employer and employee are relevant for both outcomes. Considering the importance of the assessment of RTW-ES after a prolonged period of sickness absence among employees who are not fully disabled, this knowledge is essential for the assessment of RTW-ES and the RTW process itself.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.OECD . Transforming disability into ability: policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland Elliott K. Long term sickness absence. BMJ. 2005;330(7495):802–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7495.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young AE, Roessler RT, Wasiak R, McPherson KM, van Poppel MN, Anema JR. A developmental conceptualization of return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):557–568. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-8034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasiak R, Young AE, Roessler RT, McPherson KM, van Poppel MN, Anema JR. Measuring return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(4):766–781. doi: 10.1007/s10926-007-9101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muijzer A, Groothoff JW, de Boer WE, Geertzen JH, Brouwer S. The assessment of efforts to return to work in the European Union. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(6):689–694. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Post M, Krol B, Groothoff JW. Work-related determinants of return to work of employees on long-term sickness absence. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(9):481–488. doi: 10.1080/09638280400018601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner BT, Pransky G, Shaw WS, Nha Hong Q, Loisel P. Researcher perspectives on competencies of return-to-work coordinators. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(1):72–78. doi: 10.3109/09638280903195278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwers EP, Terluin B, Tiemens BG, Verhaak PF. Predicting return to work in employees sick-listed due to minor mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(4):323–332. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9198-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brouwer S, Krol B, Reneman MF, Bultmann U, Franche RL, van der Klink JJ, et al. Behavioral determinants as predictors of return to work after long-term sickness absence: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(2):166–174. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause N, Frank JW, Dasinger LK, Sullivan TJ, Sinclair SJ. Determinants of duration of disability and return-to-work after work-related injury and illness: challenges for future research. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(4):464–484. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franche RL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1020270407044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacKenzie EJ, Morris JA, Jr, Jurkovich GJ, Yasui Y, Cushing BM, Burgess AR, et al. Return to work following injury: the role of economic, social, and job-related factors. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1630–1637. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.11.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, Meloche GR, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, et al. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(23):2720–2725. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause N, Dasinger LK, Deegan LJ, Rudolph L, Brand RJ. Psychosocial job factors and return-to-work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(4):374–392. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen N, van den Heuvel WP, Beurskens AJ, Nijhuis FJ, Schroer CA, van Eijk JT. The Demand-Control-support model as a predictor of return to work. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, de Boer AG, Blonk RW, van Dijk FJ. Supervisory behaviour as a predictor of return to work in employees absent from work due to mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(10):817–823. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.009688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durand MJ, Loisel P. Therapeutic Return to Work: Rehabilitation in the workplace. Work. 2001;17(1):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Infante-Rivard C, Lortie M. Prognostic factors for return to work after a first compensated episode of back pain. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53(7):488–494. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.7.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasinger LK, Krause N, Deegan LJ, Brand RJ, Rudolph L. Physical workplace factors and return to work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(3):323–333. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200003000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gjesdal S, Ringdal PR, Haug K, Maeland JG. Long-term sickness absence and disability pension with psychiatric diagnoses: a population-based cohort study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(4):294–301. doi: 10.1080/08039480801984024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, Alexanderson KA. Mortality in relation to disability pension: findings from a 12-year prospective population-based cohort study in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(4):341–347. doi: 10.1080/14034940601159229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opsteegh L, Reinders-Messelink HA, Schollier D, Groothoff JW, Postema K, Dijkstra PU, et al. Determinants of return to work in patients with hand disorders and hand injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(3):245–255. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gates LB, Akabas SH. Inclusion of People with Mental Health Disabilities into the Workplace: Accommodation as a Social Process. In: Schultz IZ, Rogers ES, editors. Work Accommodation and Retention in Mental Health New York: Springer; 2010. p. 375–392.