Abstract

The novel PKCθ isoform is highly expressed in T-cells, brain and skeletal muscle and originally thought to have a restricted distribution. It has been extensively studied in T-cells and shown to be important for apoptosis, T-cell activation and proliferation. Recent studies showed its presence in other tissues and importance in insulin signaling, lung surfactant secretion, intestinal barrier permeability, platelet and mast-cell functions. However, little information is available for PKCθ activation by gastrointestinal(GI) hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors. In the present study we used rat pancreatic acinar cells to explore their ability to activate PKCθ and the possible interactions with important cellular mediators of their actions. Particular attention was paid to cholecystokinin(CCK), a physiological regulator of pancreatic function and important in pathological processes affecting acinar function, like pancreatitis. PKCθ-protein/mRNA were present in the pancreatic acini, and T538-PKCθ phosphorylation/activation was stimulated only by hormones/neurotransmitters activating phospholipase C. PKCθ was activated in time- and dose-related manner by CCK, mediated 30% by high-affinity CCKA-receptor activation. CCK stimulated PKCθ translocation from cytosol to membrane. PKCθ inhibition (by pseudostrate-inhibitor or dominant negative) inhibited CCK- and TPA-stimulation of PKD, Src, RafC, PYK2, p125FAK and IKKα/β, but not basal/stimulated enzyme secretion. Also CCK- and TPA-induced PKCθ activation produced an increment in PKCθ’s direct association with AKT, RafA, RafC and Lyn. These results show for the first time PKCθ presence in pancreatic acinar cells, its activation by some GI hormones/neurotransmitters and involvement in important cell signaling pathways mediating physiological responses (enzyme secretion, proliferation, apoptosis, cytokine expression, and pathological responses like pancreatitis and cancer growth).

Keywords: PKCθ activation, pancreatic acini, CCK, signaling, pancreatic growth factors, PKC

1. Introduction

Protein kinase C θ (PKCθ) belongs to the threonine/serine kinase superfamily PKC [1]. In mammals this superfamily is comprised of 12 isoforms divided in 3 groups depending on their activation requirements: conventional PKC isoforms (α, βI, βII and γ), which activation depends on DAG and Ca2+; novel (δ, ε, η and θ), whose activation depends on DAG but not Ca2+ and atypical (λ/ι, μ and ζ), whose activation is independent from both DAG and Ca2+ [1]. Once activated by phosphorylation and cofactor binding [2], PKCs stimulate serine/threonine phosphorylation of many cellular proteins including other kinases, cytoskeletal proteins, structural proteins, enzymes, adapter proteins and receptors, and their activation has multiple effects in both normal and pathological processes including differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, cell death, secretion, adhesion and cell migration [3].

The novel PKCθ isoform, which is the most recently described [4], was originally thought to have a restrictive distribution with high expression in T-cells [4], brain [4] and skeletal muscle [4]. Its activation and effect on various cellular processes have been primarily studied in these tissues, especially in T-cells [5]. Numerous subsequent studies show PKCθ is more widely distributed than originally described [4] and it has been detected in a number of other tissues such as in testis [4], intestinal epithelial cells [6] and mast cells [7]; and in several human tumor and tumor cell lines [such as human gastrointestinal stromal tumor [8], human colorectal cancer [9] and gastric cancer cells KATO-III [10]].

Studies demonstrate PKCθ activation plays an important function in various tissues including T cell antigen receptor (TCR) activation, proliferation, apoptosis [5]; insulin secretion [11], insulin signaling in muscle [12], barrier permeability in intestinal epithelium [6]; thrombus formation in platelets [13] and mast cell activation [7]. However, there is little information on the activation of PKCθ by gastrointestinal (GI) hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors.

Pancreatic acinar cells are an excellent model system to study kinase activation by GI hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors because many GI hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors can alter pancreatic acinar function and signaling cascades including phospholipases (A, C, D), adenylate cyclase, tyrosine kinases and other serine/threonine kinases [14–19]. In pancreatic acinar cells from normals or animals with pancreatic disorders (pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer), PKC activation, including conventional and other novels PKCs (PKCδ and PKCε), has been implicated in several processes. These include enzyme secretion, activation of proteases, inflammatory responses, growth and apoptotic pathways stimulated by various pancreatic hormones/neurotransmitters or growth factors, as well as other stimulants [20–24]. At present, it is unclear whether PKCθ is present in pancreatic acinar cells, whether any pancreatic neurotransmitter/hormones or growth factors can activate it or whether it participates in any of signaling cascades mediating either the physiological or pathological processes caused by pancreatic neurotransmitter/hormones or growth factor stimulation of pancreatic acinar cells.

The purpose of the present study was to address these issues and to determine whether PKCθ is present in pancreatic acinar cells, if gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters can activate this novel protein kinase, PKCθ, and if so, to provide insights into the possible mechanisms of its interactions with various known important cellular mediators of the actions of these pancreatic stimulants. Particular attention was paid to the hormone/neurotransmitter, cholecystokinin (CCK), because it is not only a physiological regulator of pancreatic acinar cell function, it is also important in a number of important pathological processes affecting acinar cell function, such as pancreatitis [23,25,26].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (150–250 g) were obtained from the Small Animals Section, Veterinary Resources Branch, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD. Rabbit anti-phospho-protein kinase C θ (PKCθ) pT538, rabbit anti-PKCθ, rabbit anti-phospho-Src family (Y416), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (T202/Y204) (E10), rabbit anti-Akt, rabbit anti-RafA, rabbit monoclonal anti-RafB (55C6), rabbit anti-RafC, rabbit anti-protein kinase D (PKD), rabbit anti-protein kinase δ (PKCδ), rabbit anti-14-3-3-γ, rabbit monoclonal anti-Bcl-10 (C78F1), rabbit anti-Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue translocation gene 1 (MALT-1), rabbit anti-c-Cbl, rabbit anti-phospho Akt (T308), rabbit anti-phospho-I κ B kinase (IKK) IKKα (Ser180)/IKKβ (Ser181), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho Raf C (56A6), rabbit phospho-PKD (Ser744/748), rabbit phospho-FAK (Tyr397), rabbit phospho-Pyk2 (Tyr402), rabbit phospho-PKCδ (Tyr311), rabbit anti-α/β tubulin antibodies and nonfat dry milk were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-PKCθ (E-7) antibody, mouse monoclonal anti-Lyn (H-7), mouse anti-pan Src, bovine anti-goat horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugate and anti-rabbit-HRP-conjugate antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-PKCθ (clone 27) was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-cadherin (36/E) antibody was from BD Transduction laboratories (Lexington, KY). Mouse monoclonal anti-calpain (15C10) antibody was from Biosource International, Inc. (Camarillo, CA). Rabbit anti-phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase p85 (PI3K) was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (lake Placid, NY). Tris/HCl pH 8.0 and 7.5 were from Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, VA). 2-mercaptoethanol, protein assay solution, sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS) and Tris/Glycine/SDS (10X) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). MgCl2, CaCl2, Tris/HCl 1M pH 7.5 and Tris/Glycine buffer (10x) were from Quality Biological, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Minimal essential media (MEM) vitamin solution, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Waymouth’s medium, basal medium Eagle (BME) amino acids 100x, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), glutamine (200 mM), Tris-Glycine gels, L-glutamine, fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.05% trypsine/EDTA solution, penicillin-streptomycin, Alexa 594, Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and glycerol were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). COOH-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin (CCK), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), bombesin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), endothelin and secretin were from Bachem Bioscience Inc. (King of Prussia, PA). CCK-JMV-180 (CCK-JMV) was obtained from Research Plus Inc., Bayonne, NJ. Epidermal growth factor (EGF), thapsigargin, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), deoxycholic acid, protein kinase C isoenzyme Sample Kit and myristolated PKCθ pseudosubstrate were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Carbachol, insulin, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 12-O-tetradecanoylphobol-13-acetate (TPA), 8-bromoadenosine 3′5′ cyclic monophosphate sodium (8-Bromo-cAMP), L-glutamic acid, glucose, fumaric acid, pyruvic acid, trypsin inhibitor, HEPES, TWEEN® 20, Triton X-100, phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), sucrose, sodium-orthovanadate, sodium azide, Nonidet P40, sodium pyrophosphate, β-glycerophosphate, sodium fluoride, dithiothreitol, AEBSF, MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid), methanol and CelLytic™ M Cell Lysis Reagent were from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Albumin standard, Protein G agarose beads and Super Signal West (Pico, Dura) chemiluminescent substrate were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Protease inhibitor tablets, pepstatin, leupeptine and aprotine were from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Purified collagenase (type CLSPA) was from Worthington Biochemicals (Freehold, NJ). Nitrocellulose membranes were from Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience, Inc. (Keene, NH). Biocoat collagen I Cellware 60 mm dishes were from Becton Dickinsen Labware (Bedford, MA). Albumin bovine fraction V was from MP Biomedical (Solon, OH). NaCl, KCl, acetone, phosphoric acid and NaH2PO4 were from Mallinckrodt (Paris, KY). HEK 293 cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus, Quick Titer™ Adenovirus Quantification Kit and ViraBind™ Adenovirus Purification Kit were from Cell Biolabs, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Ad-CMV-Null was from Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA). RNA PCR Kit, DNA-polymerase (Amplitaq Gold), 10x PCR buffer and deoxynucleotides were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). L-364,718 (3S(−)-N-(2,3-dihydro-1-methyl-2-oxo-5-phenyl-1H-1,4-benzodiazepine-3-yl-1H-indole-2-carboxamide) and L-365,260 (3R(+)-N-(2,3-dihydro-1-methyl-2-oxo-5-phenyl-1H-1,4-benzodiazepin-3-yl)-N′-(3-methylphenyl)urea) were from Merck, Sharp and Dohme (West point, PA). YM022 ((R)-1-[2,3-dihydro-1-(2′-methyl-phenacyl) - 2 - oxo - 5-phenyl-1H-1,4-benzodiazepin -3-yl]-3-(3-methylphenyl)urea) and SR27897 (1-[[2-(4-(2-chlorophenyl)-thiazol-2-yl)aminocarbonyl] indolyl]acetic acid were from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Phadebas reagent was from Magle Life Science (Lund, Sweden). PKC Assay Kit and Histone H1 were from Millipore (Temecula, CA). [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) was from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Tissue Preparation

Pancreatic acini were obtained by collagenase digestion as previously described [17]. Standard incubation solution contained 25.5 mM HEPES (pH 7.45), 98 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 2.5 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM sodium glutamate, 5 mM sodium fumarate, 11.5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM glutamine, 1% (w/v) albumin, 0.01% (w/v) trypsin inhibitor, 1% (v/v) vitamin mixture and 1% (v/v) amino acid mixture.

2.2.2. Acini Stimulation

After collagenase digestion, dispersed acini were pre-incubated in standard incubation solution for 2 hrs at 37 °C with or without inhibitors as described previously [17,27]. Protein concentration was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. Equal amounts of samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

2.2.3. cDNA preparation

Random hexamer-primed first strand cDNA was obtained with RT (RNA PCR Kit) from mRNA from rat muscle, pancreas and brain (Stratagene, Clontech and Bio-chain, respectively).

PCR

Primers for PKCθ was selected through analysis of the rat PKCθ mRNA sequence (GenBank accession no AB020614.1). The sense and antisense sequences of the PKCθ primer were as follows: sense, 5′-TAGAAAGGGAGGCCAAGGAT-3′ (nucleotides 236–256); and antisense, 5′-CTGAAGGGTGGGTCAATCTC-3′ (nucleotides 367–386) giving a PCR product size of 151 bp. The presence of the PKCθ mRNA was determined in cDNA samples from rat muscle, pancreas and brain, using genomic DNA as negative control. The PCR was conducted with 40 cycles, which were within the linear amplification range. The PCR began with a cycle of 94 C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 40 sec (denaturing), 58 °C for 40 sec (annealing), and 72 °C for 40 sec (elongation.) A final extension period of 94 °C for 5 min concluded the amplification. PCR products were size-fractionated on agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

2.2.4. Western Blotting/immunoprecipitation

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously [19]. The intensity of the protein bands was measured using Kodak ID Image Analysis, which were assessed in the linear detection range. When re-probing was necessary membranes were incubated in Stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed twice for 10 min in washing buffer, blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer at room temperature and re-probed as described above.

2.2.5. Translocation

Translocation studies were performed as described previously [16]. Briefly, after stimulation, acini were resuspended in membrane lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium azide, 1 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and one protease inhibitor tablet per 10 ml). After homogenization, lysates were cleared by centrifugation. The supernatant (cytosol and membrane fraction) was centrifuged for 30 min at 4 °C and 60,000×g. The pellet containing the membrane fraction was washed twice in membrane lysis buffer, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium azide, 1 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and one protease inhibitor tablet per 10 ml), sonicated and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. Equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

2.2.6. Immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence imaging

After treating isolated pancreatic acini with or without stimulants as indicated, cells were fixed, transferred to glass slides and blocked as previously described [28], then slides were incubated with a rabbit anti-pT538 PKCθ antibody and a mouse anti-cadherin antibody at a dilution of 1:500 overnight at 4 °C. Reactivity was demonstrated by incubation with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit or with an Alexa 555-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody, respectively, at a dilution of 1:500 for 2 hours RT. Negative controls consisted of replacement of primary antibody with an isotype-matched control. Slides were analyzed as previously reported [28].

2.2.7. Amylase release

Amylase release from isolated pancreatic acinar cells was measured as previously described [29,30]. Amylase activity was determined with the Phadebas reagent and expressed as % of total cellular amylase released into the extracellular medium during the incubation time.

2.2.8. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-IP studies were performed as previously described [14]. Briefly, cell were lysated with CelLytic Buffer (CelLytic™ M Cell Lysis Reagent 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and one protease inhibitor tablet per 10 ml), and lysates (750 μg/ml) were incubated with 4 μg of the required antibody and with 25 μl of protein G-agarose at 4 °C, overnight. The immunoprecipitates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

2.2.9. Virus infection and culture acini

Pancreatic acini were isolated as described above, infected with either Ad-CMV-Null (empty adenovirus, as infection control) or dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus at 1×109 VP/ml concentration, as described previously [18]. After 6 h, stimulants were added and cells lysed as described above.

2.2.10. PKCθ kinase activation assay

PKCθ kinase activation was measured as previously described [14]. Briefly, after isolation and incubation with 10 nM CCK or 1 μM TPA, 1 and 2.5 min, respectively, pancreatic acinar cells were lysated, PKCθ was immunoprecipitated with 4 μg BD PKCθ antibody and 25 μl Protein G agarose beads overnight, 4 °C Kinase assays were performed on the PKCθ immunoprecipitates in two different ways: one using the PKC substrate peptide (QKRPSQRSKYL) provided by the PKC kinase assay kit from Millipore (Temecula, CA), following the directions provided by the manufacturer; and the other using Histone H1 (1μg/sample). The substrate peptide was spotted on to p81 filter paper and processed according to the manufactures instructions. When PKCθ kinase activity was measure as increments in the 32P-phosphorylation of the protein histone H1, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 15 μl of loading buffer and 5 min at 95 °C, samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, gels dried and analyzed in a phosphor imager (InstantImager, Packard Instruments Co.

2.2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using the Student’s t-test for paired data using the software StatView (SAS Institute, Casy, NC). P values <0.05 were considered significant. Curve fitting, EC50 and tmax were determined using the GraphPad 5.0 software.

3. Results

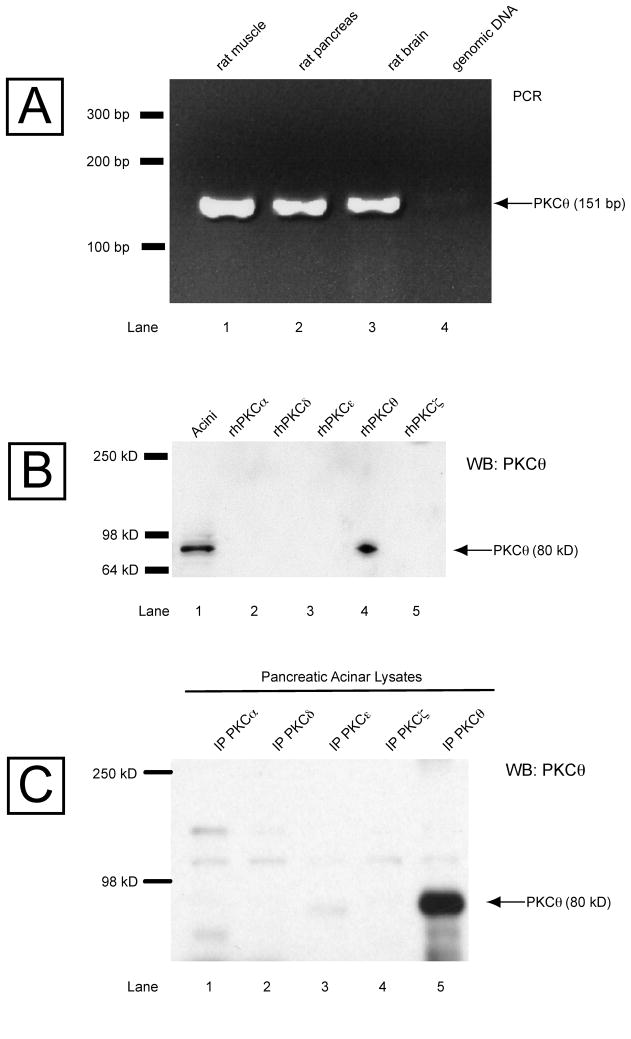

3.1. Presence of PKCθ mRNA and protein in pancreas

It is well established that four PKC isoforms (α, δ, ε, ζ) are expressed in rat pancreatic acini [14,24], but also there are contradictory data regarding the presence in this tissue of the novel isoform PKCθ [24,29,31,32]. In order to clarify this point, both studies of the presence in rat pancreas of PKCθ mRNA and PKCθ protein were determined (Fig. 1). PCR using specific primers for PKCθ mRNA with cDNAs obtained from brain, muscle (tissues known to express this enzyme) and rat pancreas was performed, and it resulted in a single band of 151 bp in all cases (Fig. 1, Panel A, Row 1–3). To determine whether the PKCθ protein is present in pancreatic acini, a Western blot was perform with different human recombinant PKC isoforms running in parallel with lysate obtained from rat pancreas acini (Fig. 1, Panel B). Immunodetected with a PKCθ total antibody (Cell Signaling), resulting in a single band of 80 kD in the pancreatic acinar lysate and only with recombinant human PKCθ (Fig. 1, Panel B, Row 1 and 4), showing the presence of PKCθ protein in rat pancreatic acini. The specificity of the PKCθ antibody used was assessed by immunoprecipitation of the known isoforms present in the lysates of the pancreas acini (α, δ, ε, ζ) with PKC specific antibodies as well as with a PKCθ antibody (BD Bioscience), with subsequent analysis by Western blot, using a different total PKCθ antibody (Cell Signaling) for the immunodetection. Only one band of 80 kDa was detected in the lane corresponding to the immunoprecipitation with the total PKCθ antibody (Fig. 1, Panel C, Row 5), demonstrating the specificity of the antibodies for PKCθ.

Fig. 1. Presence of PKCθ mRNA and protein in pancreas.

Panel A: PCR results using PKCθ specific primers and cDNA from rat muscle and rat brain, known to contain PKCθ, and from rat pancreas. Panel B: Presence of the protein PKCθ in isolated pancreatic acini. Lysates from pancreatic acini were run in parallel with different human recombinant PKC isoforms (α, δ, ε, θ and ζ) and detected by Western blotting (WB) with a specific anti-PKCθ antibody (Cell signaling). Panel C: Specificity of PKCθ antibodies was examined by immunoprecipitation (IP) of the PKC isoforms (α, δ, ε, θ and ζ) from pancreatic acini lysate with a specific anti-PKCθ anti-mouse antibody (BD Biosciences) and detection with a specific anti-PKCθ anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling). A single band was obtained just in the case of PKCθ isoform, showing the specificity of the antibodies used.

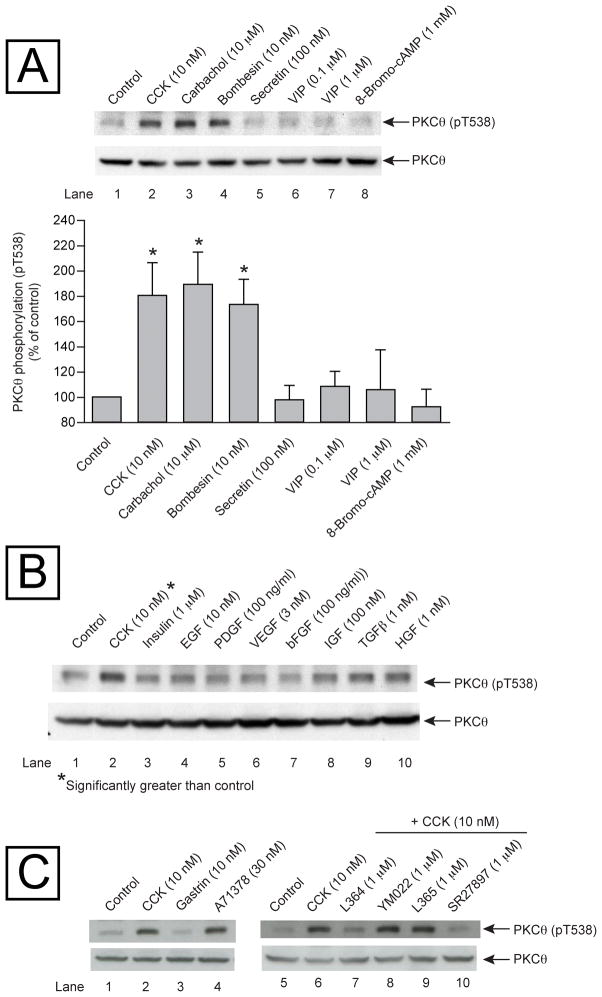

3.2. Ability of various pancreatic secretagogues and pancreatic growth factors to stimulate PKCθ phosphorylation (pT538) in rat pancreatic acini

In order to establish whether PKCθ is not only expressed but also activated by known pancreatic secretagogues or growth factors [15], rat pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence and presence of several gastrointestinal hormones (CCK, carbachol, bombesin, secretin, VIP) known to activate pancreatic acinar cells and cause enzyme secretion [15]. The pancreatic secretagogues that activate phospholipase C (CCK, carbachol and bombesin) stimulated a significant increase in the PKCθ phosphorylation in threonine 538 (pT538) (Fig. 2, Panel A, Rows 2–4). Neither of the gastrointestinal hormones (VIP and secretin) that cause an increase in the cAMP, nor the cAMP analog, 8-Bromo-cAMP were able to increase the phosphorylation of PKCθ T538 (Fig. 2, Panel A, Rows 5–8). As a measurement of PKCθ activity the phosphorylation of T538 of PKCθ was assessed because it is known that an increase in the threonine 538 phosphorylation of PKCθ is directly related to the activation of this enzyme [33].

Fig. 2. Ability of various pancreatic secretagogues and growth factors to stimulate PKCθ phosphorylation (pT538) in rat pancreatic acini.

Panel A: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of different pancreatic secretagogues for 5 minutes, and then lysed. Western blots were analyzed using anti-pT538 PKCθ and anti-Total PKCθ (PKCθ), as loading control. Top: Results of a representative blot of 5 independent experiments are shown. Bottom: Means±S.E. of 5 independent experiments. Results are expressed as % of control. * p<0.05 compared to the control group. Panel B: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of different growth factors for 5 minutes and HGF for 10 minutes, and then lysed. Western blots were analyzed using anti-pT538 PKCθ and anti-Total PKCθ (as loading control). Results of a representative blot of 4 independent experiments are shown. *= significantly greater than control. Panel C: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of CCK, gastrin or A71378 for 1 min, or preincubated for 5 min in the presence of L364,718 YM022, L365,260 or SR27897 and then in the additional presence of CCK 10 nM for 1 min, and then lysed. Western blots were analyzed using anti-pT538 PKCθ and anti-Total PKCθ (as loading control).

None of the known pancreatic growth factors (insulin, EGF, PDGF, VEGF, bFGF, IGF, TGFβ and HGF) [15] were able to activate PKCθ and stimulate threonine 538 phosphorylation of PKCθ (Fig. 2, Panel B, Rows 3–10). This lack of stimulation was not due to the inability of the growth factors to activate acinar cells because each stimulated pS473 Akt phosphorylation (data not shown).

In order to determine if any of the CCK stimulating effect on pT538 PKCθ phosphorylation was caused to the presence/activation of CCKA or CCKB receptors in the pancreatic acinar cell, isolated acinar cells were first incubated with either CCK, gastrin, or a known CCKA receptor agonist (A71378) [34] (Fig. 2, Panel C, Lanes 1–4). Gastrin did not produce any increase in pT538 PKCθ phosphorylation, and that the CCK activation of PKCθ was mimicked by the incubation of the cells with the CCKA receptor agonist. Moreover, when the acinar cells were incubated with CCK and two different CCKA receptor antagonists [L364,718 or SR27897] [30,35] the increment in PKCθ phosphorylation observed in the sole presence of CCK was completely inhibited, but not in the presence of CCKB receptor antagonists [L365 or YM022] [30,36](Fig. 2, Panel C, Lanes 5–10). These results demonstrate that the observed effect of CCK in PKCθ phosphorylation is only due to the activation of the CCKA receptors.

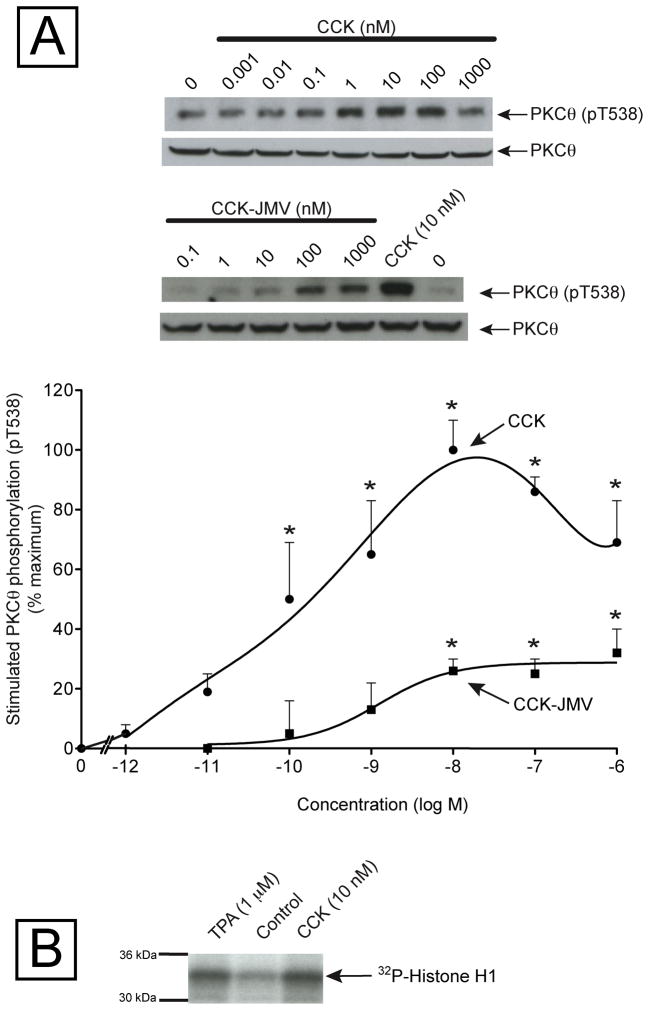

3.3. Dose-response effect of CCK and CCK-JMV on PKCθ T538 phosphorylation in rat pancreatic acini

As CCK has an important role in both the physiology and pathophysiology of the pancreas [15,37], we focused our study in the activation of PKCθ exerted by this hormone in rat pancreatic acini. Increasing concentrations of CCK produced a biphasic increase in T538 phosphorylation of PKCθ with concentrations from 0.1 nM to 10 nM causing increasing stimulation, and then concentrations from 100 to 1000 nM CCK causing less stimulation (Fig. 3, Panel A). The maximal stimulation occurred with 10 nM CCK (239±25% of control = 100±10% of maximal response) and CCK’s half-maximal effect (EC50) occurred with 0.174±0.008 nM (Fig. 3, Panel A). The CCKA receptor in pancreatic acini can exist in two different activation states, a low and a high-affinity state, and the activation of the different states activates different cell signaling cascades [18,26,38–40]. In order to determine the contribution of each activation receptor state to the activation of PKCθ by CCK, pancreatic acini were incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of CCK-JMV, known to be an agonist of the CCKA high affinity state and an antagonist of the low affinity CCKA receptor state in rat pancreatic acini [18,19]. CCK-JMV stimulated threonine 538 phosphorylation of PKCθ in a monophasic manner with concentrations from 10 nM to 1000 nM (Fig. 3) with an EC50 of 1.262±0.033 nM (Fig. 3, Panel A), and therefore was 7-times less potent than CCK. CCK-JMV caused 32% of the maximal stimulation of T538 PKCθ phosphorylation caused by CCK (Fig. 3, Panel A). These results support the conclusion that CCK stimulation of PKCθ activation is mediated 30% by the high affinity state CCKA receptor and 70% by activation of the low affinity CCKA receptor state. As a CCK concentration of 10 nM produces the maximal stimulation of PKCθ phosphorylation, it was selected for the rest of the study.

Fig. 3. Dose-response effect of CCK and CCK-JMV on PKCθ phosphorylation in rat pancreas acini.

Panel A: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of CCK and CCK-JMV for 1 minute, lysed and subjected to Western blotting as described in Fig. legend 2. Top: Results of a representative blot of 4–5 experiments is shown. Bottom: Means±S.E. of 4–5 independent experiments, with CCK or CCK-JMV, respectively. Results are expressed as % of maximal stimulation caused by CCK. * p<0.05 compared to the control with no additions.

Panel B: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of CCK or TPA for 2.5 min, and then lysed. PKCθ was immunoprecipitated from equal amount of protein (1 mg/ml) and subjected to kinase activity measurement, as outlined in the Material and Methods. This result is a representative experiment of 5 others.

To further demonstrate that CCK was activating PKCθ, we studied its ability to stimulate and increase in PKCθ kinase activity (Table 1, Fig. 3, Panel B). Both CCK and TPA produced a significant increment in the phosphorylation of the Histone H1 protein (Fig. 3, Panel B) and PKC substrate peptide (Table 1) which was assessed after performing PKCθ immunoprecipitation from pancreatic acinar cells, previously stimulated with CCK or TPA (Fig. 3, Panel B).

Table 1.

Effect of CCK and TPA on PKCθ kinase activity

| Stimulant | % Kinase Activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Substrate peptide | Histone H1 | |

| None | 100±1 | 100±2 |

| CCK (10 nM) | 139±4** | 142±4** |

| TPA (1 μM) | 235±22** | 173±30* |

PKCθ kinase activity is expressed as the percentage of phosphorylation of either a substrate peptide or Histone H1 protein, as outlined in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as Means±S.E. of 5 independent experiments

p<0.0001,

p<0.005 vs control.

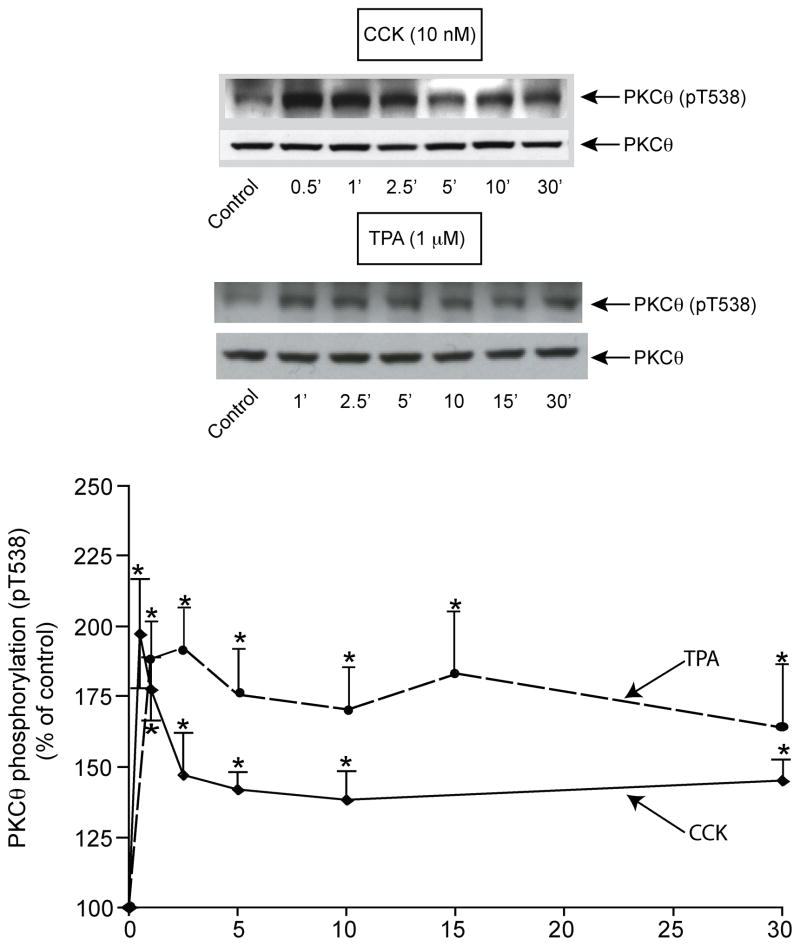

3.4. Time course of CCK stimulation of PKCθ T538 phosphorylation in rat pancreatic acini

Stimulation of pT538 threonine phosphorylation by CCK was rapid and the time course was biphasic (Fig. 4). Specifically, CCK stimulated a rapid initial increase reaching a maximum within 1 min (tmax: 0.78±0.08 min) (maximum: 197±19% of control). Subsequently, the magnitude of pT538 phosphorylation stimulated by CCK was significantly less than the maximal but was greater than the basal level for 30 min (145±11% of control) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Time course of CCK and TPA stimulation of PKCθ T538 phosphorylation in rat pancreatic acini.

Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated in the absence or presence of CCK or TPA for the indicated times, lysed and subjected to Western blotting as described in Fig. legend 2. Top: Results of a representative blot of 5 independent experiments are shown. Bottom: Means±S.E. of 5 independent experiments. Results are expressed as % of control. * p<0.05 compared to the control value (i.e. 0 time).

Because phospholipase C (PLC) stimulating pancreatic hormones, which subsequently activate PKC, stimulated PKCθ T538 phosphorylation, the ability of TPA, a known PKC activator, to stimulate PKCθ T538 phosphorylation at different times, was also studied (Fig. 4). TPA produced, as in the case of CCK, a rapid (1 minute) and significant increase (188±13% of control) in PKCθ pT538 phosphorylation (Fig. 4). This increase was maintained for 5 minutes, and then the stimulation slowly decreased over a 30 min period but still remained significantly above the control level (30 min, 171±23% of control). With TPA, the tmax value (1.60±0.06 min) was longer than that seen with CCK stimulation.

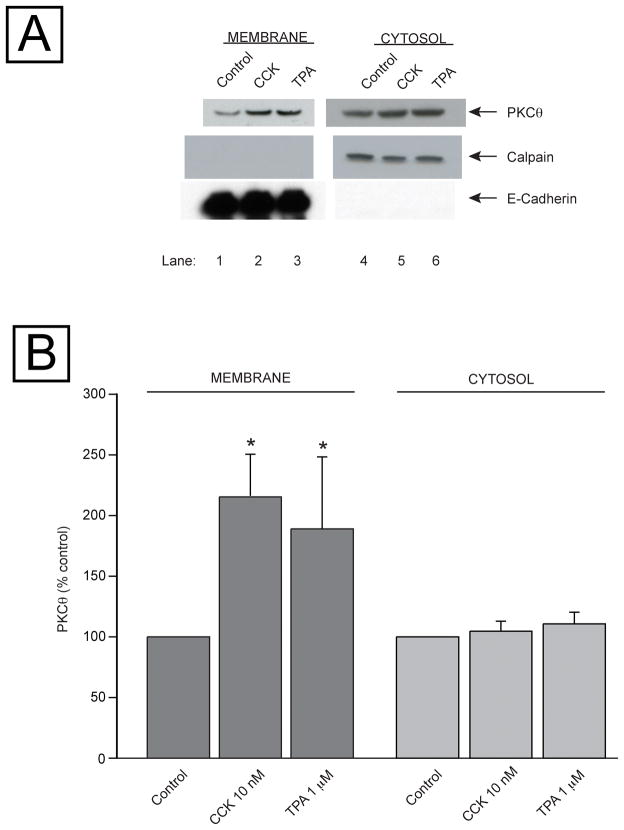

3.5. Ability of CCK and TPA to stimulate translocation of PKCθ to the cell membranes in rat pancreatic acinar cells

Because PKCθ translocation to the plasma membranes as well as its pT538 phosphorylation are needed for activation [33,41] we examined the ability of CCK and TPA to cause translocation of total PKCθ. CCK or TPA produced a significant increment in the membrane associated PKCθ after 1 min or 5 min incubation, 216±34 and 189±59% of control p<0.05, respectively (Fig. 5, Panels A (Lanes 1–3) and Panel B). These incubation times were chosen because this is when both stimulants exerted their maximum effects on PKCθ phosphorylation (Fig. 4). To confirm the separation of the cytosol and membranes fractions was adequate, equal protein amounts of each fraction were subjected to Western blot and immunodetection was performed with either with E-cadherin (membrane fraction) or calpain (cytosol marker) antibody (Fig. 5, Panel A). This immunodetection also showed equal loading in each experiment condition and good separation of the cytosol and membranes fractions (Fig. 5, Panel A).

Fig. 5. Ability of CCK and TPA to stimulate translocation of PKCθ to the cell membranes in rat pancreatic acinar cells.

Isolated acini were incubated with or without CCK or TPA for 1 or 5 min, respectively. Samples were processed as described in Methods to obtain subcellular fractions, and then subjected to Western blotting. Panel A: results from one experiment representative of 5 separate experiments. In the upper panel, membranes were analyzed using anti-PKCθ antibody. Lower 2 panels: to assess the effectiveness of subcellular fractionation, the cytosol and membrane fractions were analyzed using anti-calpain antibody, a marker for the cytosol fraction, and anti-E-Cadherin Ab, a marker for the membrane fraction. Panel B shows the mean values ± S.E. of 5 independent experiments. Results are expressed as % of control. * p< 0.05 compared to the control group.

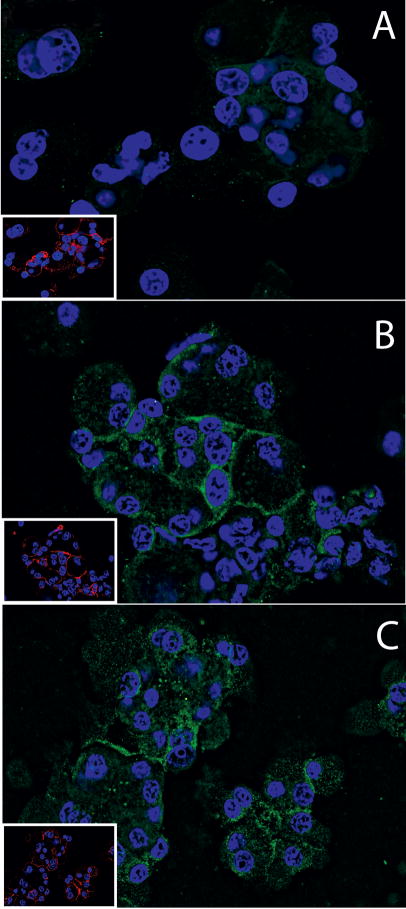

We also studied the translocation of PKCθ to the membrane after stimulation with CCK or TPA by immunofluorescense-cytochemistry, and we observed that in the absence of CCK or TPA, PKCθ was homogenously distributed through the cytoplasm (Fig. 6, Panel A). After TPA or CCK treatment, the phosphoT538 PKCθ was increased in the membrane in both cases (Panel B and C, Fig. 6, respectively), with the increase caused by TPA more prominent. This results were similar to those obtain by the membrane fractionating approach (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. PKCθ immunofluorescense-cytochemistry in rat pancreatic acini with and without TPA or CCK treatment.

Pancreatic acini were incubated with no additions, TPA (1 μM) or CCK (10 nM) for 10 minutes. After stimulation cells were washed, fixed, permeabilized and transferred onto poly-l-lysine coated glass slides by cytocentrifugation as described in Methods. Cells were then labeled using polyclonal rabbit anti-pT538 PKCθ (Cell Signaling) and mouse anti E-cadherin primary antibodies. Specific binding was detected using an Alexa 488- and Alexa 555-conjugated secondary antibodies, respectively, so that green staining represents staining for pT538 PKCθ and red staining represents E-cadherin (in inserts). Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (blue). Fluorescent images were collected using a Leica CTR5000 microscope. Panel A shows acini treated with incubation buffer only (control). Panels B–C show cells treated for 10 min with 1 μM TPA or 10 nM CCK. Shown are results of a typical experiment representative of 4 independent experiments. Cells shown are representative of > 90% of total cells present.

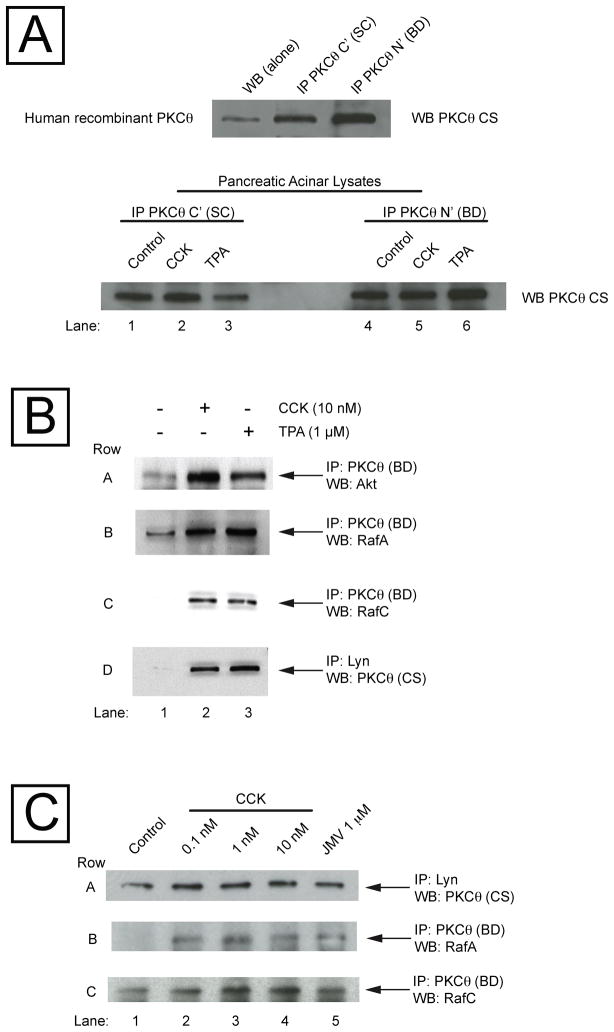

3.6. Ability of CCK and TPA to stimulate the association of PKCθ with various cellular proteins in rat pancreatic acinar cells

PKCθ is reported to interact with a number of other important cellular signaling proteins in different cell types including Src, [41], PKD [42], Raf [42], CARMA and IKK [43], Cbl [44], 14-3-3 [45], Blc-10 [46], MALT-1 [47] and Akt [12], kinases known to be particularly important in regulating growth and apoptosis. In order to determine the possible interaction of PKCθ with these proteins in the pancreatic acini, we studied the ability of CCK or TPA to stimulate a direct interaction of PKCθ with these proteins by performing co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) studies (Fig. 7). We first tested 2 different PKCθ antibodies abilities to immunoprecipitate PKCθ, one that recognized the N terminal sequence of PKCθ (BD Bioscience) and another that recognizes the C terminal sequence of PKCθ (Santa Cruz: SC) (Fig. 7, Panel A). We observed that both PKCθ antibodies were able to immunoprecipitate the PKCθ isoform from human recombinant PKCθ protein solution and from rat pancreatic acini incubated in the absence or presence of CCK (10 nM) and TPA (1 μM), respectively. We next investigated the Co-IP of PKCθ and the different proteins after incubation with CCK (10 nM) or TPA (1 μM), concentrations that caused a maximal PKCθ activation. CCK (10 nM) (Fig. 7, Panel B, Lane 2) and TPA (1 μM) (Fig. 7, Panel B, Lane 3) produced an increase in the association of PKCθ with Akt, RafA, RafC and the Src kinase, Lyn (Fig. 7, Panel B, Row A–D), but not with MALT-1, Bcl-10, 14-3-3γ or Cbl (data not shown). To ensure that the antibody used for immunoprecipitation was not the cause of lack of association, we repeated the Co-IP experiments using the other PKCθ antibody for the immunoprecipitation and MALT-1, Bcl-10, 14-3-3γ or Cbl antibody for the immunodetection, and also in the reverse direction: immunoprecipitating with MALT-1, Bcl-10, 14-3-3γ or Cbl antibody and immunodetection with both PKCθ antibodies, and we did not obtained any stimulated association with PKCθ by after incubation with CCK or TPA.

Fig. 7. Ability of CCK and TPA to stimulate the association of PKCθ with Akt, RafA, RafC and Lyn, in rat pancreatic acinar cells.

Panel A: Human recombinant PKCθ protein solution and pancreatic acinar lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-C terminal (Santa Cruz: SC) or N terminal anti- PKCθ antibody (BD Bioscience: BD), or directly subjected to Western blot (WB alone), and subsequent immunodetected with a different anti-PKCθ antibody (Cell Signaling: CS). Panel B: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated for 2.5 min in the absence and presence of CCK or TPA. Equal amounts of proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PKCθ (BD) or anti-Lyn antibody, and then subjected to Western blotting, using as first antibody anti-Akt, anti-PKCθ (Cell Signaling), anti-RafA or anti-RafC antibody. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Panel C: Isolated pancreatic acini were incubated for 2.5 min in the absence and presence of CCK or JMV. Equal amounts of proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PKCθ (BD) or anti-Lyn antibody, and then subjected to Western blotting, using as first antibody anti-PKCθ (Cell Signaling), anti-RafA or anti-RafC antibody. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

In order to establish whether this direct association of PKCθ with other kinases was produced at low (physiological) or high (supraphysiological) CCK concentrations, Co-IP experiments were performed with CCK concentrations that occupy the high or low affinity receptor states (CCK concentrations: 0.1–1–10 nM) and also with CCK-JMV, known to be an agonist only of the CCKA high affinity state and an antagonist of the low affinity CCKA receptor state in rat pancreatic acini [18,19]. And we have found that the direct association of PKCθ with either Lyn, RafA or RafC was observed also at low CCK concentration and with CCK-JMV (Fig. 7, Panel C). CCK-JMV stimulated an association of 33±12 % of that exerted by CCK 10 nM, a value that was not different from that observed in the T538 PKCθ phosphorylation exerted by JMV in relation to CCK 10 nM (Fig. 3, Panel A).

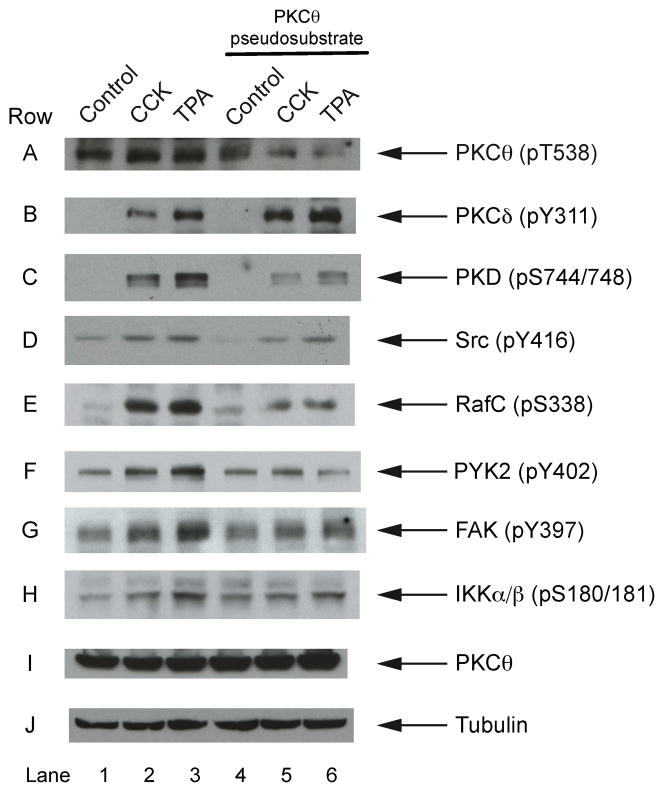

3. 7. Effects of PKCθ inhibition by PKCθ pseudosubstrate on the phosphorylation of various cellular signaling molecules

In order to investigate further the role of this PKCθ activation in stimulating various intracellular signaling cascades in pancreatic acini, we used a PKCθ inhibitor, a PKCθ pseudosubstrate. This is a cell-permeable myristolyated peptide, and a selective and competitive inhibitor of this PKC isoenzyme that includes amino acids 113–125 of the pseudosubstrate sequence. The pseudosubstrate produced an inhibition of the pT538 phosphorylation of PKCθ stimulated by CCK (48±3% vs CCK alone p<0.003) or TPA (57±4% vs TPA alone p<0.003) (Fig. 8, Row A), but it did not affect the phosphorylation of another novel PKC isoform, PKCδ, known to be present in the pancreas and to be activated by CCK or TPA [17,48] (Fig. 8, Row B). The possibility of blocking the activation of PKCθ give us the opportunity to study the effect of this inhibitor on the activation of kinases known to be stimulated in pancreatic acini by CCK, such as PKD, Src, RafC, RafA, PYK2, FAK, IKK, Akt, and p44/42 MAPKs and to assess whether they could be activated by PKCθ. The inhibition of PKCθ by the PKCθ pseudosubstrate inhibitor decreased the phosphorylation of PKD stimulated by either CCK or TPA (Fig. 8, Row C, Lane 2–3) (19.4±3.69 and 19.1±3.0 folds over control, respectively, both p<0.05) to values still above the control, but significantly reduced (69±3% and 75±3%, respectively vs stimulant alone, both p<0.04; Fig. 8, Row C, Lane 5–6). Similarly, CCK- and TPA-stimulated Src pY416 phosphorylation was inhibited (59±3% and 46±6% vs stimulant alone, p<0.02 and p<0.04, respectively; Fig. 8, Row D, Lane 2–3 and 5–6), RafC (39±6% and 33±64 vs stimulant alone, p<0.02 and p<0.01, respectively; Fig. 8, Row E, Lane 2–3 and 5–6). The PKCθ pseudosubstrate partially inhibited CCK or TPA phosphorylation of pY402 of PYK2 (73±5% and 71±8% vs stimulant alone, both p<0.05, respectively; Fig. 8 Row F, Lane 2–3 and 5–6), pY397 phosphorylation of p125FAK (73±5% and 71±8% vs stimulant alone, p<0.02 and p<0.01, respectively; Fig. 8, Row G, Lane 2–3 and 5–6) and pS180/181 phosphorylation of IKKα/β (55±6% and 56±5% vs stimulant alone, p<0.04 and p<0.03, respectively; Fig. 8, Row H, Lane 2–3 and 5–6). However, the increment/decrement in the phosphorylation state of other kinases produce by CCK or TPA in pancreatic acinar cells, such as Akt and p44/42 MAPKs, RafA, or p85 PI3K was not affected by the presence of the PKCθ inhibitor, supporting the conclusion that activation of PKCθ in pancreatic acini is not implicated in the activation of these enzymes by CCK or TPA.

Fig. 8. Effects of PKCθ inhibition by PKCθ pseudosubstrate in the phosphorylation of PKD, Src, RafC, PYK2, FAK and IKK.

Isolated pancreas acini were preincubated with or without 20 μM PKCθ pseudosubstrate for 3 hours and then incubated in the absence or additional presence of CCK (10 nM) or TPA (1 μM) for 2.5 and 5 min, respectively, and then lysed. Western blots were analyzed using anti-pT538 PKCθ, anti-pY311 PKCδ, anti-pS744/748 PKD, anti-pY416 Src, anti-pS338 RafC, anti-pY402 PYK2, anti-pY397 FAK, anti-pS180/181 IKKα/β and, as loading control, anti-PKCθ and anti-α/β tubulin antibodies. Results are representative of 10 independent experiments.

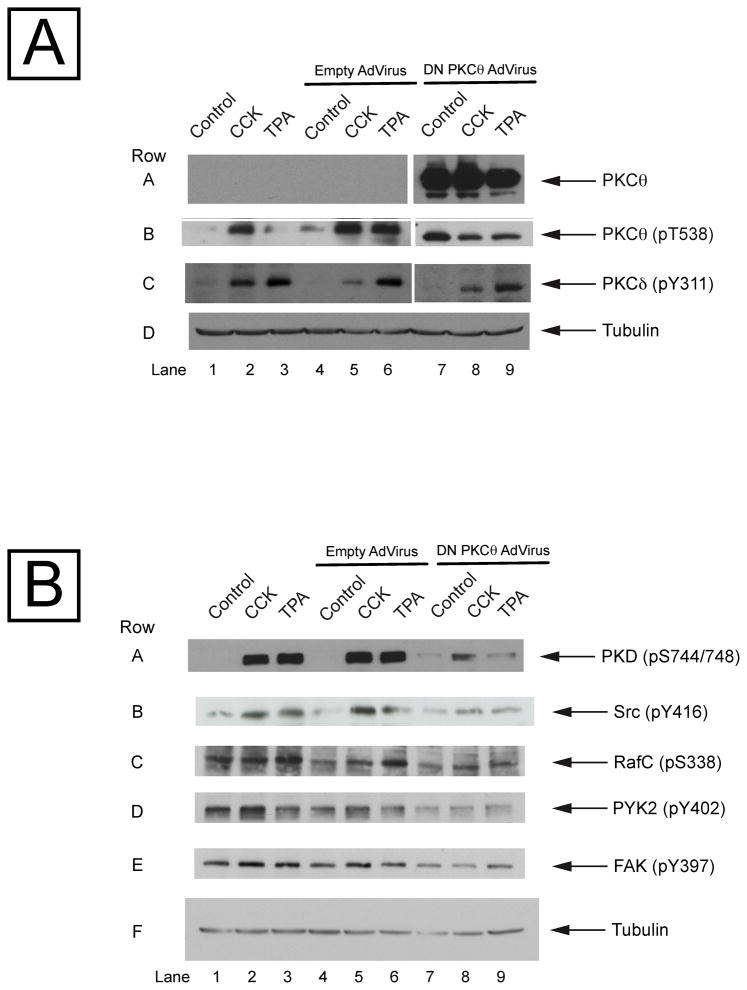

3.8. Effects of PKCθ inhibition by dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus on the phosphorylation of various cellular signaling molecules

In order to confirm the results obtained with the PKCθ pseudosubstrate inhibitor, we used another approach, inhibition by a dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus. This virus contains in its genome a copy of the PKCθ DNA human sequence with a K/R point mutation at the ATP binding site which renders it inactive. The infection of pancreatic acini with this adenovirus produces over-expression of the mutated PKCθ, where it can function as a dominant negative. Isolated pancreatic acini were infected for 6 h in the absence or presence of 109 pfu/mg [18] empty adenovirus (control of infection) or the dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus, and then incubated in the absence or additional presence of CCK and TPA. After the 6 hours incubation, an overexpression in PKCθ could be observed (Fig. 9, Panel A, Row A). Moreover, in no case did the infection with the empty adenovirus resulted in unusual PKCθ expression or result in a change in the ability by CCK or TPA to stimulate pT538 phosphorylation of PKCθ itself (Fig. 9, Panel A and B, Rows A-F, Lanes 4–6). These results supported the conclusion that if any change in the phosphorylation of the enzyme was observed it would be due to the dominant negative PKCθ, and not because of the adenovirus infection. Over-expression of the dominant negative PKCθ did not alter the increment in the PKCδ phosphorylation induced by CCK or TPA (Fig. 9, Panel A, Row C), but it produced a completely inhibition of the pT538 PKCθ phosphorylation (Fig. 9, Panel A, Row B), showing that the inhibition of the PKCθ dominant negative adenoviruses is specific and it is not affecting the activation of another novel PKC isoform, PKCδ, which is known to be expressed and activated by CCK in the pancreatic acini [17,48].

Fig. 9. Effects of PKCθ inhibition by dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus in the phosphorylation of PKD, Src, RafC, PYK2 and FAK.

Isolated pancreas acini were cultured as described in Methods and infected without and with an empty adenovirus or a dominant negative PKCθ adenovirus for 6 hours, incubated in the absence or additional presence of CCK (10 nM) or TPA (1 μM) for 2.5 and 5 min, respectively, and then lysed. Western blots were analyzed using: Panel A: anti-PKCθ, anti-pT538 PKCθ, anti-pY311 PKCδ and, as loading control, anti-α/β tubulin antibodies; Panel B: anti-pS744/748 PKD, anti-pY416 Src, anti-pS338 RafC, anti-pY402 PYK2, anti-pY397 FAK and, as loading control, anti-α/β tubulin antibodies. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

The over-expression of the dominant negative PKCθ produced a marked decreased in the stimulation caused by CCK or TPA in the phosphorylation of PKD, Src, RafC, PYK2 and FAK (Fig. 9, Panel B, Rows A–E, Lanes 1–3 vs 7–9), similar to what was observed when cells were preincubated in the presence of the PKCθ pseudosubstrate inhibitor (Fig. 8).

3.9. Effects of PKCθ inhibition in amylase release

In order to study the possible implication of PKCθ activation in the stimulation of amylase release in rat acinar cells, isolated acini were preincubated in the presence of 20 μM PKCθ pseudosubstrate inhibitor and subsequently incubated with different stimulants (Table 2). The preincubation with the PKCθ inhibitor did not produce any modification in the stimulation in the amylase secretion by CCK, carbachol or VIP, all known stimulants of pancreatic acinar cells secretion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of PKCθ inhibition on Amylase Secretion

| Secretagogue | Amylase secretion (% total)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| −PKCθ inhibitor | +PKCθ inhibitor | |

| None | 1.7±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 |

| CCK (0.03 nM) | 5.1±0.8 | 5.8±0.9 |

| (0.1 nM) | 7.1±0.6 | 7.4±0.6 |

| (100 nM) | 4.5±0.4 | 4.5±0.3 |

| Carbachol (1 μM) | 6.8±0.7 | 7.0±0.5 |

| (1 mM) | 6.2±0.7 | 6.3±0.6 |

| VIP (10 nM) | 3.4±0.6 | 3.6±0.4 |

Pancreatic acini were pre-incubated for 2 hours with 20 μM PKCθ pseudosubstrate and then for 15 minutes with the indicated secretagogues. Amylase secretion is expressed as the percentage of the total acinar cell amylase released into the medium during the incubation. Results are means±S.E. from 6 different experiments.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters can activate the novel protein kinase, PKCθ, and if so, to provide insights into the possible mechanisms of its interactions with various known important cellular mediators of the actions of these GI stimulants. This was performed studying pancreatic acinar cells after first determining whether PKCθ is present in the cells. Particular attention was paid to the hormone/neurotransmitter, cholecystokinin (CCK), because it is not only a physiological regulator of pancreatic acinar cell function, it is also important in a number of important pathological processes affecting acinar cell function, such as pancreatitis [23,25,26].

The ability of GI hormones/neurotransmitters and GI growth factors to activate PKCθ was investigated using pancreatic acinar cells for a number of reasons. First, pancreatic acini are known to be highly responsive and activated by numerous GI hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors, and this cell system has been widely used as a model system to study the cellular signaling and effects of these stimulants [14–17]. Second, there is very little information on the ability of gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters or growth factors to activate this novel PKC. Third, previous studies have demonstrated activation of other novel PKC’s (PKCδ, ε), as well as the conventional PKC, PKCα, are important in mediating some of CCK’s physiological and pathophysiological effects in the pancreas, as well as the effects on these cells by a number of other gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors [14,20,21,24,48,49].

A number of our results support the conclusion that PKCθ is present in pancreatic acinar cells, even though previous studies have presented conflicting results. In a recent review of PKCs in pancreatic acinar cells, as well as in four different studies [20,50–52], only four of the 12 known PKCs isoforms were reported to be present in pancreatic acinar cells and PKCθ was not one of them (PKCα, δ, ε and ζ). However, in other studies the presence of PKCθ has been found in two pancreatic acinar tumor cell lines (TUC3 and BMRPA.430) [29,32], reported to be present weakly in one study using immunoblotting in isolated rat pancreatic acinar cell lysates [32] and to be present in acinar cells from human pancreas in 15% of the cases studied [31], as well as to be present in guinea pig pancreatic duct cells [53] and pancreatic islet rat β-cells [11]. We established PKCθ was present in rat pancreatic acini using three different approaches. First, we established PKCθ was present using immunoblotting and detection with antibodies specific for PKCθ, which under the experimental conditions used in the present study, did not cross-react with other PKCs, including novel PKCs (δ, ε) known to be present in acinar cells [20,50–52]. The specificity of the results for pancreatic acinar cells was established by preparing dispersed isolated rat pancreatic acini and detecting PKCθ in these cells and comparing the result with known PKC standards assessed under identical assay conditions, which established the specificity of the antibodies used for the detection of PKCθ. Second, we detected the presence of PKCθ mRNA by PCR using primers specific for PKCθ mRNA and demonstrated that the PCR product was similar with that found in two other tissues known to contain the PKCθ isoform, muscle and brain. Third, we demonstrated by immunofluorescence using a specific PKCθ antibody, the presence of PKCθ in isolated rat pancreatic acini in the cytoplasm and its subsequent translocation to the acinar cell membrane after the acini were exposed to a known physiological stimulant of pancreatic acinar function, CCK [25].

In this study we next assessed the ability of various GI hormones/neurotransmitters, as well as GI growth factors to activate PKCθ. A number of our results support the conclusion that pancreatic stimulants that interact with G-protein-coupled receptors in acinar cells and stimulate phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated pathways, but not other cascades, nor pancreatic growth factors, activate PKCθ. First, only carbachol, bombesin and CCK, all known to activate the PLC-cascade in pancreatic acinar cells [15], and not GI hormones/neurotransmitters which activate adenylate cyclase (VIP or secretin) or stimulate directly PKA (8-Br-cAMP) [15] stimulated T538 PKCθ phosphorylation. Second, none of the known pancreatic growth factors (insulin, EGF, PDGF, VEGF, bFGF, IGF and HGF) stimulated T538 PKCθ phosphorylation. This lack of activation by growth factors was not due to their inability to stimulate pancreatic acinar cells because previous studies show specific receptors for these growth factors exist on these cells and their activation stimulates a number of cellular signaling cascades [15,19]. Moreover, we demonstrated that the increase activation of PKCθ by CCK is due to the activation of CCKA receptor only, and not due to the binding of CCK to a possible CCKB/gastrin receptor that could be present in the rat pancreatic acinar cell or other accompanying cells. Although in other species, CCKB receptors are present in pancreatic acinar cells and they are present in the rat pancreatic acinar cell line, AR42J cells, or results are consistent with other studies which demonstrate only CCKA receptors on rat pancreatic acini[15,40,54].

To assess activation of PKCθ in the present study we used three different approaches, first stimulation of T538 PKCθ phosphorylation, second stimulation of PKCθ translocation, and third measurement of stimulation of PKCθ kinase activity. T538 PKCθ phosphorylation was assessed because previous studies shown that PKCθ is phosphorylated in 3 different sites (T538, S695 and S676), with its activation of kinase catalytic activity [1,2]. The phosphorylation of the T538 site plays an essential role in PKCθ activation, because mutation of this site leads to a PKCθ that does not undergo activation or translocation with known stimulants [33]. Furthermore, there is a close correlation between the PKCθ T538 phosphorylation state and its kinase catalytic activity [47]. For that reason, increments in phosphorylation of T538 PKCθ have been widely used to assess PKCθ activation in a number of tissues including, not only in T cells or T cell lines [10,47], but also in a number of other cells [13]. Thirdly, we also demonstrated PKCθ’s activation by demonstrating its translocation to membranes when stimulated by some of these agents. Once phosphorylated by its activators, PKC isoforms translocate to the membrane where they can phosphorylate various protein/substrates. In fact, after stimulation PKCθ has been shown to translocate to membranes in T cells [55], muscle cells [56] and mast cells [7]. We demonstrate in rat pancreatic acinar cell with stimulation by CCK there is an increase membrane-associated PKCθ. These results were established through two different approaches, first using Western blotting and immunodetection of PKCθ with specific PKCθ antibodies in fractionated membranes from rat pancreatic acinar cell and demonstrating an increase of PKCθ in membranes after incubation with CCK or TPA (PKC activator); and second, using immunofluorescence in isolated rat pancreatic acinar cells with specific PKCθ antibodies, treatment with CCK or TPA resulted in the accumulation of phospho-T538 PKCθ in the membrane. These results have some similarities and differences from previous studies of the ability of various agents to activate PKCθ in other tissues. They are similar in that a number of other GI hormones/neurotransmitters in other systems can also activate PKCθ. Specifically, muscarinic cholinergic agents activate PKCθ in muscle [57] and bombesin-related peptides in human antral G cells [58]. There are no studies reporting the ability of agents that activate adenylate cyclase/PKA to stimulate PKCθ. However, our results with activation of PKCθ differ from studies with other novel PKC isoforms in other tissues, which demonstrate both dBcAMP/8-Br-cAMP/CPT-cAMP or agents that activate adenylate cyclase, can stimulate their activation. Specifically, synthetic cAMP analogs activate PKCδ in hepatocytes [59] and VIP activates PKCδ in cortical astrocytes [60]. Our results with growth factors differ from studies reporting that insulin is able to increase PKCθ activation in myocytes [56], EGF increases T538 PKCθ phosphorylation in A431 cells [61] and that IGF-1 increases PKCθ catalytic activity in rhabdomyosarcoma cell line [62]. These results demonstrate that a selected group of GI hormones/neurotransmitters that activate the PLC cascade can activate PKCθ in pancreatic acinar cells. However, our results with growth factors differ from the results reported in some other tissues suggesting PKCθ responsiveness may be tissue-specific. Furthermore, the lack of response to cAMP/PKA agents in pancreatic acinar cells, suggests PKCθ responsiveness to this signaling cascade, differs from that reported for the GI hormone/neurotransmitter VIP, as well as for other stimulants, for other novel isoform of PKCs in other tissues, suggesting the PKCθ responsiveness to the agents may also be tissue specific or novel PKC subtype specific.

Numerous studies support the conclusion that in pancreatic acinar cells, the CCKA receptor exists in two different states, a high affinity and low affinity state, each of which activates different signaling cascades [15,26,63]. In the present study CCK’s stimulation of T538 PKCθ phosphorylation was detectable at 0.1 nM, with a half-maximal effect at 0.174 nM and a maximal effect at 10 nM in pancreatic acinar cells. These results have both similarities and differences from the ability of CCK to stimulate other novel PKC kinases in pancreatic acinar cells. Specifically, CCK-stimulated maximal PKCmu (PKD1) activation at a similar concentration to that observed for PKCθ (10 nM), however 10-fold higher CCK concentrations were required to fully activate PKCδ (100 nM). These results demonstrate different novel PKCs in pancreatic acinar cells have different dose-response curves for CCK activation. Several results from this study support the conclusion that full activation of PKCθ by CCK in pancreatic acini requires activation of both, the high and low, CCKA affinity receptor states. Activation of PKCθ in pancreatic acinar cells by CCK occurs over a 5-log-fold range of CCK concentrations, with PKCθ stimulation occurring with CCK concentrations which has been shown in other studies to activate both the high and the low affinity CCKA receptor states [15,38]. This conclusion is supported by the results with the synthetic analog, CCK-JMV, which, in rat pancreatic acinar cells, functions as an agonist of the high affinity CCK receptor state and an antagonist of the low affinity receptor state [15,38,39]. CCK-JMV produced 30% of the maximal PKCθ activation exerted by CCK. As CCK-JMV is an agonist of only the high affinity CCKA [39], these results with CCK-JMV demonstrate that CCK causes 30% of its maximal PKCθ activation through activation of the high affinity CCKA receptor state and the remaining 70% of maximal activation is due to activation of low affinity CCKA receptor state. These results show similarities and differences from CCKA receptor-mediated phosphorylation of other kinases or proteins in pancreatic acinar cells. PKCθ activation by CCK is similar to CCK-mediated activation of the Src kinase, Lyn[64], PYK2/CAKβ [17], p125FAK [27], paxillin [16] and the novel PKC, PKCmu (PKD1) [18] in pancreatic acinar cells, in that in each case, maximal activation requires CCKAR activation of both the high and the low states. However, these different signaling cascades differ in the relative importance of the high affinity and low affinity CCK receptor states. Activation of the high affinity CCKA receptor state is responsible for only 20% of the maximal activation of PKCmu (PKD1) [18] and PYK2/CAKβ [17], whereas it mediates 50% of the maximal stimulation of p125FAK and paxillin phosphorylation [65] and mediates 60% of Lyn activation [64]. These results with PKCθ activation differ from results seen with CCK activation in pancreatic acinar cells of the novel PKC, PKCδ [14] or stimulation of phosphorylation of the adaptor protein, CrKII, [66] where are mediated only through activation of the low affinity CCKA receptor state. In contrast, CCK-mediated activation of PI-3 kinase and phospholipase D in pancreatic acinar cells is mediated entirely by the activation of the high affinity receptor state [67]. These results demonstrate that not only do the CCKA receptor states differ in their coupling to pancreatic cellular kinase cascades, but even with different novel PKCs in the same cell, the CCKAR receptor activation states show differential coupling.

In other cells activated by various stimulants, PKCθ activation is known to be important in the stimulation of a number of important cellular signaling proteins [5], including Src, [41], PKD [42], Raf [42,68], CARMA and IKK/NFκβ [43], Cbl [44,47], 14-3-3 [45], Blc-10 [46], MALT-1 [47], PI3K [19], ERK [13], IRS-1 [12], p125FAK [69] and Akt [12]. In pancreatic acinar cells, stimulation by growth factors and GPCRs causes activation of a number of these cellular signaling proteins, including Src kinases [64], PKD [18,49], Raf [70], IKKα/β/NFκβ [49], PI3K [19,71], p44/42 MAPKs [72], p125FAK, PYK2 and paxillin and Akt [19], which have been shown to be important in mediating cell activation, enzyme secretion [73,74], proliferation and apoptosis [19], cell survival [75] and protein synthesis [76]. Furthermore, activation of a number of these signaling pathways such as NFκβ play a critical role in pathological processes such as inflammatory and cell death responses of pancreatic acinar cells in acute pancreatitis [21,49,72]. A number of our results support the conclusion that PKCθ activation by CCK or TPA plays an important role in the activation of a number of these cellular signaling cascades in pancreatic acinar cells. First, using a specific pseudosubstrate PKCθ inhibitor [22] we observed a decrease in the CCK- and TPA-stimulated phosphorylation/activation of PKD1 (PKCmu), Src, RafC, PYK2, p125FAK and IKKα/β, but no effect on phosphorylation/activation of AKT or p44/42 MAPKs. Second, with specific inhibition of the PKCθ activation by the overexpression, in isolated pancreatic acinar cells, of a PKCθ dominant negative form by adenovirus infection, we found also a decrease in the CCK- and TPA-stimulated phosphorylation/activation of PKD1 (PKCmu), Src, RafC, PYK2, FAK and IKKα/β, but no effect on AKT or p44/42 MAPKs phosphorylation/activation. That these results were specific for PKCθ were supporting by the findings that neither the pseudosubstrate PKCθ inhibitor nor the dominant negative PKCθ, altered the activity of PKCδ, another novel PKC expressed in acinar cells [14]. These results show similarities and some important differences from results with PKCθ activation reported in other studies in other tissues. They are similar to results with PKD activation in COS-7 and Jurkat cells, which was dependent on PKCθ activation [42] and in the case of activation of the IKKα/β-NFκβ pathway in T cells by CD3/CD28, which is also dependent on PKCθ activation [5]. They differ in that we found no alteration by the inhibition of PKCθ activation in the phosphorylation/activation of AKT or p44/42 MAPK with pancreatic acinar cells stimulated by either CCK or TPA, which are well-established stimulants in pancreatic acini of both AKT [19] and p44/42 MAPK [77]. Previous studies have provided evidence that other two novel PKCs (PKCδ, PKCε) found in pancreatic acinar cells, are activated by CCK and TPA [14,20,21,48], and their activation is important for a number of physiological and pathological responses of the acinar cell [49]. Our results support the conclusion that PKCθ is also involved in the activation of many of these cellular signaling cascades involved in several of these effects in pancreatic acinar cells, and in future studies, which of the three novel kinases is most important in producing these various cell effects will need to be investigated.

Our results not only provide evidence for the participation of PKCθ in the activation of other kinases in pancreatic acinar cells, but also support the conclusion that it can affect various signaling cascades by a direct association of this novel PKC isoform, observed not only at high but also at low doses, with different protein/kinases implicated in various cellular signaling cascades. This conclusion is supported by the results of our co-immunoprecipitation experiments, which showed that both CCK- and TPA-stimulated the association of PKCθ with the Src kinase, Lyn; AKT; RafA and RafC, but not an association with p85 PI3K, PKD1, RafB, Bcl-10, Cbl, MALT-1, tubulin or 14-3-3 protein. These results have similarities and differences with other studies in other tissues. They are similar in the case of the direct association of PKCθ with a member of the Src kinase family, because in Jurkat, RBL-2H3 and T cells co-stimulation by CD3/CD28, produces an increase in the direct association of PKCθ with Src kinases (Src, Lyn, Lck and Fyn) [41,46,55]; and in the case of Raf proteins in Cos-1 transfected cells with PKCθ and Raf proteins, upon stimulation with TPA, a direct association of PKCθ with RafC and RafB occurred [68]. Our results show also differences with other studies in other tissues, which reported a direct association of PKCθ with PI3K, Cbl, Bcl-10, MALT-1, tubulin and 14-3-3 protein [44,45,47]. They also differ from other studies in that for the first time we find with pancreatic acinar cells activation of PKCθ stimulated a direct associate with AKT, which has been shown to be important in mediating pancreatic processes including enzyme secretion or apoptosis and in pathological processes, such as pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer growth [19,78].

The role of other PKC novel isoforms in amylase release in rat pancreatic acinar cells is controversial with one study [79] concluding that PKCδ is not implicated in this secretory effect of CCK or carbachol in acinar cells from guinea pigs or PKCδ−/− rats. Another study [20], though, proposed that the PKCδ isoform, and not the PKCε, is important in mediating amylase release. Our results support the conclusion that, PKCθ, is not implicated in the amylase secretion produced by CCK, carbachol or VIP, as its inhibition did not alter the amylase release evoked by secretagogues either activating phospholipase C or adenylate cyclase.

Research highlights.

Establishes PKCθ is expressed in pancreatic acinar cells.

PKCθ is activated by pancreatic stimulants activating phospholipase C or PKC, but not by those activating PKA or pancreatic growth factors.

PKCθ is activated in time- and dose-related manner by CCK with 30% of CCK’s maximal stimulation mediated by activation of the high-affinity CCKA-receptor state and the remainder by activation of the low affinity receptor state.

PKCθ activation by CCK and TPA produces an increment in PKCθ’s direct association with AKT, RafA, RafC and Lyn.

Inhibition of PKCθ either using an antagonist pseudosubstrate or dominant negative construct produces a reduction in the CCK- and TPA-stimulation of PKD1, Src, Raf C, PYK2, p125FAK and IKKα/β, but not basal or stimulated enzyme secretion.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK, NIH.

Abbreviations

- CCK

COOH-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin

- TPA

12-Otetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- GI

gastrointestinal

- CCK-JMV

CCK-JMV-180

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- Co-IP

coimmunoprecipitation

- PKD

protein kinase D

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- PYK2

proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- IKK

IκB kinase

- AKT

protein kinase B

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- PKA

protein kinase A

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- 8-Br-cAMP

8-Bromo-cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- TCR

T-cell Receptor

- PLC

phospholipase C

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- MAPK/ERK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate 1

- CARMA

caspase recruitment domain (CARD) carrying member of the membrane associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family proteins

- MALT-1

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue translocation gene 1

- Cbl

Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene

- Bcl-10

B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 10 protein

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3-

- Kinase

CAKβ, cell adhesion kinase β

- NFκβ

nuclear factor-kappa B

- PAR2

protease-activated receptor 2

- PAR4

protease-activated receptor 4

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Parekh DB, Ziegler W, Parker PJ. Multiple pathways control protein kinase C phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2000;19:496–503. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keranen LM, Dutil EM, Newton AC. Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1394–1403. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28495–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baier G, Telford D, Giampa L, Coggeshall KM, Baier-Bitterlich G, Isakov N, Altman A. Molecular cloning and characterization of PKC theta, a novel member of the protein kinase C (PKC) gene family expressed predominantly in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4997–5004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isakov N, Altman A. Protein kinase C(theta) in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:761–794. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banan A, Zhang LJ, Shaikh M, Fields JZ, Farhadi A, Keshavarzian A. Theta-isoform of PKC is required for alterations in cytoskeletal dynamics and barrier permeability in intestinal epithelium: a novel function for PKC-theta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C218–C234. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00575.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Graham C, Parravicini V, Brown MJ, Rivera J, Shaw S. Protein kinase C theta is expressed in mast cells and is functionally involved in Fcepsilon receptor I signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:831–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blay P, Astudillo A, Buesa JM, Campo E, Abad M, Garcia-Garcia J, Miquel R, Marco V, Sierra M, Losa R, Lacave A, Brana A, Balbin M, Freije JM. Protein kinase C theta is highly expressed in gastrointestinal stromal tumors but not in other mesenchymal neoplasias. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4089–4095. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuranami M, Cohen AM, Guillem JG. Analyses of protein kinase C isoform expression in a colorectal cancer liver metastasis model. Am J Surg. 1995;169:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pazos Y, Alvarez CJ, Camina JP, Casanueva FF. Stimulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases and proliferation in the human gastric cancer cells KATO-III by obestatin. Growth Factors. 2007;25:373–381. doi: 10.1080/08977190801889313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warwar N, Efendic S, Ostenson CG, Haber EP, Cerasi E, Nesher R. Dynamics of glucose-induced localization of PKC isoenzymes in pancreatic beta-cells: diabetes-related changes in the GK rat. Diabetes. 2006;55:590–599. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Soos TJ, Li X, Wu J, Degennaro M, Sun X, Littman DR, Birnbaum MJ, Polakiewicz RD. Protein kinase C Theta inhibits insulin signaling by phosphorylating IRS1 at Ser(1101) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45304–45307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagy B, Jr, Bhavaraju K, Getz T, Bynagari YS, Kim S, Kunapuli SP. Impaired activation of platelets lacking protein kinase C-theta isoform. Blood. 2009;113:2557–2567. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tapia JA, Garcia-Marin LJ, Jensen RT. Cholecystokinin-stimulated protein kinase C-delta activation, tyrosine phosphorylation and translocation is mediated by Src tyrosine kinases in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;12:35220–35230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen RT. Receptors on Pancreatic Acinar Cells. In: Johnson LR, Jacobson ED, Christensen J, Alpers DH, Walsh JH, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 3. Vol. 2. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1377–1446. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia LJ, Rosado JA, Gonzalez A, Jensen RT. Cholecystokinin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of p125FAK and paxillin is mediated by phospholipase C-dependent and -independent mechanisms and requires the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton and participation of p21rho. Biochem J. 1997;327:461–472. doi: 10.1042/bj3270461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tapia JA, Ferris HA, Jensen RT, Marin LJ. Cholecystokinin activates PYK2/CAKβ, by a phospholipase C-dependent mechanism, and its association with the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31261–31271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Tapia JA, Thill M, Pace A, Mantey SA, Jensen RT. CCK causes PKD1 activation in pancreatic acini by signaling through PKC-delta and PKC-independent pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:483–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berna MJ, Tapia JA, Sancho V, Thill M, Pace A, Hoffmann KM, Gonzalez-Fernandez L, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal growth factors and hormones have divergent effects on Akt activation. Cell Signal. 2009;21:622–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, Chen X, Williams JA. Regulation of CCK-induced amylase release by PKC-delta in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol (Gastrointest Liver Physiol) 2004;287:G764–G771. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00111.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh A, Gukovskaya AS, Nieto JM, Cheng JH, Gukovsky I, Reeve JR, Jr, Shimosegawa T, Pandol SJ. PKC delta and epsilon regulate NF-κB activation induced by cholecystokinin and TNF-α in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol (Gastrointest Liver Physiol) 2004;287:G582–G591. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00087.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koon HW, Zhao D, Zhan Y, Simeonidis S, Moyer MP, Pothoulakis C. Substance P-stimulated interleukin-8 expression in human colonic epithelial cells involves protein kinase Cdelta activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1393–1400. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosen-Binker LI, Lam PP, Binker MG, Reeve J, Pandol S, Gaisano HY. Alcohol/cholecystokinin-evoked pancreatic acinar basolateral exocytosis is mediated by protein kinase C alpha phosphorylation of Munc18c. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13047–13058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorelick F, Pandol S, Thrower E. Protein kinase C in the pancreatic acinar cell. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 1):S37–S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen RT. Involvement of cholecystokinin/gastrin-related peptides and their receptors in clinical gastrointestinal disorders. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91:333–350. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lankisch TO, Nozu F, Owyang C, Tsunoda Y. High-affinity cholecystokinin type A receptor/cytosolic phospholipase A2 pathways mediate Ca2+ oscillations via a positive feedback regulation by calmodulin kinase in pancreatic acini. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:632–641. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pace A, Garcia-Marin LJ, Tapia JA, Bragado MJ, Jensen RT. Phosphospecific site tyrosine phosphorylation of p125FAK and proline-rich kinase 2 is differentially regulated by cholecystokinin receptor A activation in pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19008–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann KM, Tapia JA, Berna MJ, Thill M, Braunschweig T, Mantey S, Moody T, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal hormones cause rapid c-Met receptor down-regulation by a novel mechanism involving clathrin-mediated endocytosis and a lysosome dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37705–37719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tapia JA, Jensen RT, Garcia-Marin LJ. Rottlerin inhibits stimulated enzymatic secretion and several intracellular signaling transduction pathways in pancreatic acinar cells by a non-PKC-delta-dependent mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang SC, Zhang L, Chiang HC, Wank SA, Maton PN, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. Benzodiazepine analogues L-365,260 and L-364,718 as gastrin and pancreatic CCK receptor antagonists. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:G169–G174. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.1.G169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans JD, Cornford PA, Dodson A, Neoptolemos JP, Foster CS. Expression patterns of protein kinase C isoenzymes are characteristically modulated in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:392–402. doi: 10.1309/bkpc9dx98r781b87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raffaniello RD, Nam J, Cho I, Lin J, Bao LY, Michl J, Raufman JP. Protein kinase C isoform expression and function in transformed and non-transformed pancreatic acinar cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:8579. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparatore B, Passalacqua M, Pedrazzi M, Ledda S, Patrone M, Gaggero D, Pontremoli S, Melloni E. Role of the kinase activation loop on protein kinase C theta activity and intracellular localisation. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian JM, Rowley WH, Jensen RT. Gastrin and CCK activate phospholipase C and stimulate pepsinogen release by interacting with two distinct receptors. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:G718–G727. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.4.G718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berna MJ, Tapia JA, Sancho V, Jensen RT. Progress in developing cholecystokinin (CCK)/gastrin receptor ligands that have therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;7:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsson LI, Schwartz T, Lundqvist G, Chance RE, Sundler F, Rehfeld JF, Grimelius L, Fahrenkrug J, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell O, Moon N. Occurrence of human pancreatic polypeptide in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Possible implication in the watery diarrhea syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:675–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehfeld JF, Friis-Hansen L, Goetze JP, Hansen TV. The biology of cholecystokinin and gastrin peptides. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1154–1165. doi: 10.2174/156802607780960483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowley WH, Sato S, Huang SC, Collado-Escobar DM, Beaven MA, Wang LH, Martinez J, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. Cholecystokinin-induced formation of inositol phosphates in pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G655–G665. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.4.G655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stark HA, Sharp CM, Sutliff VE, Martinez J, Jensen RT, Gardner JD. CCK-JMV 180: a peptide that distinguishes high affinity cholecystokinin receptors from low affinity cholecystokinin receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1010:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu DH, Huang SC, Wank SA, Mantey S, Gardner JD, Jensen RT. Pancreatic receptors for cholecystokinin: Evidence for three receptor classes. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:G86–G95. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.1.G86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]