Abstract

Background

The study was conducted to evaluate the impact of out-of-pocket expense on intrauterine device (IUD) utilization among women with private insurance.

Study Design

We reviewed the records of all women with private insurance who requested an IUD for contraception from an urban academic gynecology practice from May 2007 through April 2008. For each patient, we determined the out-of-pocket expense that would be incurred, and whether she ultimately had an IUD placed. The total charge for placement of a copper or levonorgestrel IUD (including the device) was $815.

Results

Ninety-five women requested an IUD during the study period. The distribution of out-of-pocket expense was bimodal: less than $50 for 35 (37%) women and greater than $500 for 52 (55%) women. IUD insertion occurred in 24 (25%) women, 19 of whom had an out-of-pocket expense less than $50. In univariate and multivariable analysis, women with insurance coverage that resulted in less than $50 out-of-pocket expense for the IUD were more likely to have an IUD placed than women required to pay $50 or more (adjusted OR=11.4, 95% CI = 3.6, 36.6),.

Conclusions

Women requesting an IUD for contraception are significantly more likely to have an IUD placed when out-of-pocket expense is less than $50.

Keywords: IUD, insurance, contraception, out-of-pocket expense

1. Introduction

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are highly effective, due in large part to high rates of user satisfaction and continuation [1]. IUDs can be safely used by most women, including nulliparas and adolescents [2–4]. Although the upfront expense for an IUD is greater than for many other contraceptives, IUDs are cost-effective [5–7]. In 2009, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that IUDs “be offered as a first-line contraceptive method and encouraged…for most women” [1].

However, IUD utilization in the United States remains low compared to other countries. According to the latest National Survey of Family Growth (2006–2008), only 5.5% of U.S. reproductive age women using contraception use an IUD [8,9]. Barriers to IUD use include lack of clinician knowledge or skill, low patient awareness, and high upfront costs [1,5]. Increased or free coverage of contraceptive methods increases contraceptive use [10], including IUDs specifically [11]. While medical insurance generally leads to lower out-of-pocket health care expenses, the amount of coverage is variable.

Currently, there is limited data from clinical practice regarding the impact of private insurance contraceptive coverage, deductibles, and out-of-pocket expenses on IUD utilization in the U.S. Therefore, our primary aim was to assess the association between insurance coverage and placement of a desired IUD among women who requested such services.

2. Materials and methods

This retrospective cohort study included all women requesting an IUD for contraception from May 1, 2007, through April 30, 2008, at an urban, faculty gynecology practice at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, PA. This faculty practice accepted only private insurance and Medicare. The total charge by the practice for a copper or levonorgestrel IUD and insertion was $815 during the study period. The Institutional Review Board at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital approved this study.

In the faculty practice, women desiring an IUD after appropriate counseling and medical evaluation had IUD insurance coverage verified by clinic billing staff. The staff calculated expected out-of-pocket costs, recorded this information in each patient's chart, and communicated expenses to the patient by phone. Women were offered the option of using a payment plan for out-of-pocket expenses. Women who remained interested in using an IUD were then scheduled for IUD placement. The practice kept a log of all IUD insurance verifications which was used to identify women for this study.

We abstracted de-identified information on patients' demographic characteristics, individual insurance coverage for an IUD (including the out-of-pocket expense), and whether an IUD was inserted by reviewing the practice's medical records as of May 31, 2008. Total IUD expense was calculated as the cost of IUD plus the charge for IUD insertion using data provided by the practice's billing department. Out-of-pocket expense was calculated as the total charge for the IUD and placement minus any insurance coverage.

The primary outcome in this analysis was IUD placement during the study period. Insurance coverage was divided into two groups based on out-of-pocket expenses: less than $50 and $50 or more.

Distributions of demographic variables (age, race, gravidity, parity, and marital status) and out-of-pocket expense for IUD use were examined using chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Student's t-test for continuous variables. Associations of individual demographic variables with IUD use were examined using univariable logistic regression to calculate unadjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between out-of-pocket expense and IUD use while adjusting for age, race, gravidity, parity, and marital status to calculate adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

3. Results

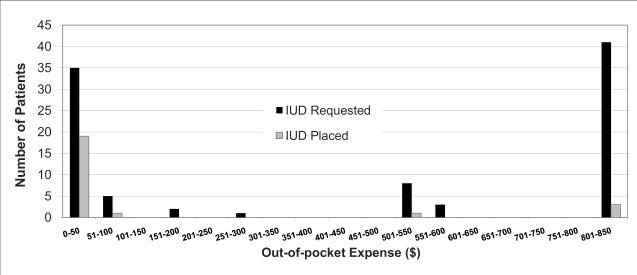

During the 12-month study period, 98 women requested an IUD for contraception; 95 (97%) charts were fully available for review. The demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. All women had private insurance; however, the out-of-pocket expense varied widely. The distribution of out-of-pocket expense was bimodal (Fig. 1) at less than $50 for 35 (37%) women and greater than $500 for 52 (55%) women. The median expense for an IUD was $540. Only 7% (7/95) of women had no out-of-pocket expense whereas 43% (41/95) had no coverage.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study populationa

| Overall (%) | IUD Placed (%) | IUD not placed (%) | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.09 | |||

| 30 or less | 49 (51.6) | 16 (32.7) | 33 (67.4) | |

| More than 30 | 46 (48.4) | 8 (17.4) | 38 (82.6) | |

| Race | 0.20 | |||

| White | 37 (39) | 12 (32.4) | 25 (67.6) | |

| Non-white | 58 (61.1) | 12 (20.7) | 46 (79.3) | |

| African American | 49 (51.6) | |||

| Asian | 3 (3.2) | |||

| Hispanic | 4 (4.2) | |||

| Unknown | 2 (2.1) | |||

| Gravidity | 0.41 | |||

| Nulligravida | 8 (8.4) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Multigravida | 87 (91.6) | 21 (24.1) | 66 (75.9) | |

| Parity | 0.73 | |||

| Nullipara | 13 (13.7) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Multipara | 82 (86.3) | 20 (24.4) | 62 (75.6) | |

| Marital status | 0.26 | |||

| Single | 50 (52.6) | 15 (30) | 35 (70) | |

| Married | 45 (47.4) | 9 (20) | 36 (80) | |

| Out-of-pocket expense | <0.001 | |||

| Less than $50 | 35 (36.8) | 19 (54.3) | 16 (45.7) | |

| $50 or more | 60 (63.2) | 5 (8.3) | 55 (91.7) |

IUD = intrauterine device.

Values presented as mean (SD) or number (%).

p-values for categorical variables generated using chi square.

Figure 1.

Out-of-pocket expenses for insured women who requested IUD placement footer:

Black = IUD

Requested Gray = IUD Placed

Out-of-pocket expenses did not vary significantly by age, marital status, gravidity, or parity (Table 2). Out-of-pocket expenses tended to be greater for non-white women though this was not statistically significant (p=0,06). The median out-of-pocket expenses for white (n=37) and non-white (n=58) women were $285 and $552, respectively. The distributions of cost did not differ significantly by race (Mann-Whitney U test p=0.16; data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and out-of-pocket expensea

| Out-of-pocket expenses | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than $50 n=35 | $50 or more n=60 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.21b | ||

| 30 or less | 21 (42.9) | 28 (57.1) | |

| More than 30 | 14 (30.4) | 32 (69.6) | |

| Race | 0.06b | ||

| Caucasian | 18 (48.7%) | 19 (51.4%) | |

| Non-Caucasian | 17 (29.3%) | 41 (70.7%) | |

| Gravidity | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 0.55c |

| Parity | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.47c |

| Marital Sstatus | |||

| Single | 21 (42%) | 29 (58%) | 0.27b |

| Married | 14 (31.1%) | 31 (68.9%) | |

IUD = intrauterine device.

Values presented as mean (SD) or number (%).

p-values for categorical variables generated using chi square.

p-values for continuous variables generated using t-test

Overall, only 25% (24/95) of women requesting an IUD had one placed. In univariable analysis, out-of-pocket cost was the only variable predictive of IUD placement (Table 3). Most IUDs (79%) were placed for women with out-of-pocket expense less than $50, including 4 of the 7 women with no out-of-pocket expense. IUD placement was performed for 19/35 (54%) women with out-of-pocket expense less than $50 and 5/60 (8%) women with out-of-pocket expense of $50 or more (OR=13.1, 95% CI = 4.2, 40.5). Three of the 5 women who received an IUD and had an out-of-pocket expense of $50 or more had no insurance coverage (out-of-pocket cost of $815). In multivariable analysis (Table 3), out-of-pocket expense remained a significant predictor for IUD placement (OR=11.4, 95% CI 3.6, 36.6).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression predicting IUD placement

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted ORa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-pocket expense | ||||

| Less than $50 | 13.1 | 4.2–40.5 | 11.4 | 3.6–36.6 |

| $50 or more (ref) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Age | ||||

| 30 or less | 2.3 | 0.9–6.1 | 2.0 | 0.7–6.4 |

| More than 30 (ref) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 1.8 | 0.7–4.7 | 1.5 | 0.4–5.5 |

| Non-Caucasian (ref) | 1.0 | -- | 1 | -- |

| Gravidity | ||||

| Nulligravida | 1.9 | 0.4–8.6 | 1.5 | 0.1–29.2 |

| Multigravida | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Parity | ||||

| Nullipara | 1.38 | 0.4–5.0 | 0.6 | 0.1–7.6 |

| Multipara | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 0.6 | 0.2–1.5 | 0.7 | 0.2–2.4 |

| Single (ref) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

IUD = intrauterine device.

Ref=referent.

Adjusted for all variables shown in table.

4. Discussion

In this cohort of privately insured women who requested an IUD, we found that many women (43%) had no coverage for IUDs, and that high out-of-pocket expense was highly associated with failure to obtain an IUD. Women requesting an IUD for contraception with an out-of-pocket expense less than $50 were significantly more likely to have an IUD placed. Women who have private health insurance should be able to receive recommended services, especially when the use of these services is highly cost-effective from the insurer's perspective [5]. However, the findings of this study indicate that high out-of-pocket expenses are associated with lower IUD placement rates, even among those with private insurance. Of further concern, non-white women tended to face greater out-of pocket expense than did white women.

Strengths of this study include data from a mix of private insurance payers in a diverse, urban environment. Though all women in our cohort had private insurance coverage, contraceptive coverage varied because Pennsylvania does not mandate insurance coverage of contraception. As compared to previous studies which examined IUD costs using online drug databases [7] and average wholesale prices [5], this analysis reports actual IUD expenses.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample from a single practice, the lack of information on women's annual income, and lack of detailed information regarding why women who requested an IUD did not ultimately have the IUD placed. For instance, some women may have found the inconvenience of returning to the office for placement a greater barrier than their out-of-pocket expense. In addition, more follow-up data on outcomes for women who did not receive a desired IUD, such as contraceptive method used in place of desired IUD and pregnancy rates, will be of interest in future studies.

This analysis highlights the important role that out-of-pocket expense plays in IUD utilization, even for women with private insurance, and strengthens previous research that has shown that “cost concerns are an important factor in contraceptive method choice and use” [12]. Eliminating prohibitive out-of-pocket expenses for IUDs will likely require a two-pronged approach. First, women in the United States need access to lower cost IUDs. While IUDs in developing countries can be purchased very cheaply, currently there are only two companies in the United States that manufacture FDA approved IUDs and both of these companies are for-profit. In contrast to other medications or devices that usually decrease in cost the longer they are on the market, the cost of IUDs has been increasing. In March of 2010 the average wholesale price of the levonorgestrel IUD in the United States increased 43%, from $586 to $843 [13].

Second, women in the United States need improved insurance coverage for IUDs. As discussion and debate about the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) continues, we are at an important crossroads for decision making. The Women's Health Amendment, the portion of the PPACA that addresses women's preventive health services, has the potential to recognize and incorporate all contraceptive options under the umbrella of women's preventive services. Recognizing contraception as part of women's preventive health services would ensure that all new private health plans provide contraception without any cost-sharing. This is an important opportunity to minimize the financial barriers to IUD use for U.S. women.

When we discuss contraceptive efficacy and effectiveness, we compare perfect versus typical use. In fact, one of the reasons IUDs are so effective is because their effectiveness with typical use is the same as the efficacy seen with perfect use. There is a similar comparison to be made here. In a perfect world, women would be willing and able to pay out-of-pocket for IUDs. However, as this analysis shows, “typical” or actual IUD use is strongly associated with expense. If we are committed to decreasing rates of unintended pregnancy, high quality IUDs at affordable prices need to be available.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gariepy was funded by an Anonymous Foundation. Dr. Patel is funded by NCI grant K07 CA120040. Dr. Schwarz was funded by NICHD grant K23 HD051585.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented as a poster abstract at Reproductive Health 2010, the Annual Meeting of the Society of Family Planning, Atlanta, GA, Sep 22–24, 2010

References

- [1].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 450. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1434–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Intrauterine device. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 59. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:223–32. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200501000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Intrauterine device and adolescents, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1493–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291575.93944.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(No. RR-4):1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chiou CF, Trussell J, Reyes E, et al. Economic analysis of contraceptives for women. Contraception. 2003;68:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, Biggs MA, Hulett D, Darney PD. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:446–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J. Cost-effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2009;79:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. (Vital and Health Statistics Series 23, No. 29). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Hubacher D, Kost K, Finer LB. Characteristics of women in the United States who use long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1349–57. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821c47c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Postlethwaite D, Trussell J, Zoolakis A, Shabear R, Petitti D. A comparison of contraceptive procurement pre- and post-benefit change. Contraception. 2007;76:360–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Testimony of Guttmacher Institute Submitted to the Committee on Preventive Services for Women, Institute of Medicine. 2011 January 12; Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/CPSW-testimony.pdf.

- [13].Trussell J. Update on the cost-effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2010;82:391. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]