Abstract

Objective

To gain insight into the pathways associated with inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface, this study examined the molecular characteristics of monocytes derived from the maternal circulation and the placental of obese women.

Study design

Mononuclear cells were isolated from placenta, venous maternal and umbilical cord blood at term delivery and, activated monocytes were separated using CD14 immunoselection. The genotype and expression pattern of the monocytes were analyzed by microarray and real time RT-PCR.

Results

The transcriptome of the maternal blood and placental CD14 monocytes exhibited 73 % homology with 10 % (1800 common genes) differentially expressed. Genes for immune sensing and regulation, matrix remodeling and lipid metabolism were enhanced 2–2006 fold in placenta compared to maternal monocytes. The CD14 placental monocytes exhibited a maternal genotype (9 % DYS14 expression) as opposed to the fetal genotype (90 % DYS14 expression) of the trophoblast cells.

Conclusion

CD14 monocytes from the maternal blood and the placenta share strong phenotypic and genotypic similarities with enhanced inflammatory pattern in the placenta. The functional traits of the CD14 blood and placental monocytes suggest that they both contribute to propagation of inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface.

Keywords: placenta, inflammation, obesity, fetus, monocytes

Introduction

The presence of macrophages in the stromal core of the placental villous suggests that the placenta has the ability to either initiate an in situ inflammatory response or to react to an exogenous inflammatory stimulus. Decidual macrophages and their cross-talks with the neighboring placenta cells are well characterized, particularly as it relates to placental invasion and the tolerance of the fetus by the maternal organism at early development stages (1, 2). By contrast, the role and function of placental resident macrophages at later stages of pregnancy is not as well understood. Inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface is a common feature of gestational pathologies in human associated with either fetal or maternal demises (3). The increased accumulation of macrophages in the placenta during pregnancy with pre-eclampsia, obesity or diabetes (4–6) suggests that disorders of maternal homeostasis have the potential to impact the placental immune function.

The knowledge on effectors and cellular pathways controlling the engagement of macrophages into the inflammatory response, their migration and maturation is rapidly extending in the context of low grade inflammation. Peripheral blood monocytes can emigrate through the endothelial barrier into various tissues under both inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions. For instance, adipose tissue macrophages of obese individuals are derived primarily from activated systemic monocytes extruding through vascular walls into the stroma vascular compartment (7, 8). Upon infiltration the monocytes differentiate into activated specialized cells with phenotypic and functional traits dictated by their cellular environment (9, 10). It is not currently known whether this infiltrating process applies to the placenta in late gestation. As point of fact the placenta being of fetal lineage harbors a population of resident macrophages, the Hofbauer cells originating from fetal myeloid cells early in development (11).

To gain insight into the pathways associated with chronic placental inflammation this study was aimed at investigating the characteristics of the monocyte macrophage populations present at the maternal-fetal interface in late gestation. Based on our previous observations that in human obesity, the placental macrophages and maternal blood monocytes are in a pro-inflammatory state (5, 11) we sought to characterize monocytes derived from both the placenta and systemic circulation of obese women. Using a gene set approach we show that placental and maternal activated monocytes exhibit common genotypic and phenotypic characteristics suggesting that they both contribute to immune crosstalks at the maternal-fetal interface.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The study cohort included 18 overweight/obese women (age 27±2, pre-gravid BMI: 35.2±1.7) with a term singleton pregnancy (38.7±0.2 weeks) of 10 male and 8 female fetuses. To rule out a potential inflammatory component related to parturition, our subjects were recruited at elective Cesarean delivery. There were no clinical or laboratory signs of infection or history of autoimmune disorders. Maternal blood was drawn on admission to labor and delivery, prior to placement of a normal saline intravenous line for hydration. Umbilical venous blood was drawn via syringe from the double clamped cord immediately after delivery of the placenta. The protocol was approved by the MetroHealth Medical Center Institutional Review Board and Clinical Research Unit Scientific Review Committee of the CTSA. Volunteers gave their written informed consent in accordance with the MetroHealth Medical Center guidelines for the protection of human subjects. Maternal body mass index (BMI) was assessed by obtaining pre-pregnancy weight by history and measured height of the women at her first antenatal visit. Birth weight, placental weight, and neonatal percent body fat recorded as described (13) were 3627±122 g, 734±43 g and 16.1+0.4 respectively.

Cell isolation and immunoselection

Placental tissue was digested with trypsin and DNase and cells were purified by density gradient centrifugation (6). The average yield was 106 cells/g of tissue with greater than 80% viability and > 85% of trophoblast cells positive for CD133. For mononuclear cells isolation venous maternal and umbilical cord blood was separated by Ficoll-paque plus (GE Healthcare, formerly Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and directly processed for CD14 immuno-selection with CD14-coupled magnetic beads (Dynalab, Invitrogen).

Flow cytometry

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) cells were incubated with fluorescent primary antibodies (CD14-PE, CD68-PE (Abcam, cambridge, MA) and CD133-FITC (Mylteni-Biotech, Auburn, CA) or control IgG. Propidium iodide was used to control for cell viability. Multicolor population analysis was performed with paint-a-gate software 3.0.0 PPC (Becton Dickinson). All gating and data analysis were performed with CELLQuest software 3.2.1f1 (Becton Dickinson).

RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from frozen placental cells using Trizol (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and from mononuclear cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Integrity of purified RNA samples was assessed by spectrometry (Agilent, SantaClara, CA). For realtime RT-PCR, cDNA were analyzed in duplicate using SYBR green (Lightcycler, Roche Molecular Diagnosis, IN). The copy number of Y chromosome was assessed from the absolute amount of DYS14 gene based on a genomic DNA standard curve 0.5 to 500 ng/ml (Promega, Madison, WI).

Transcriptional profile analysis

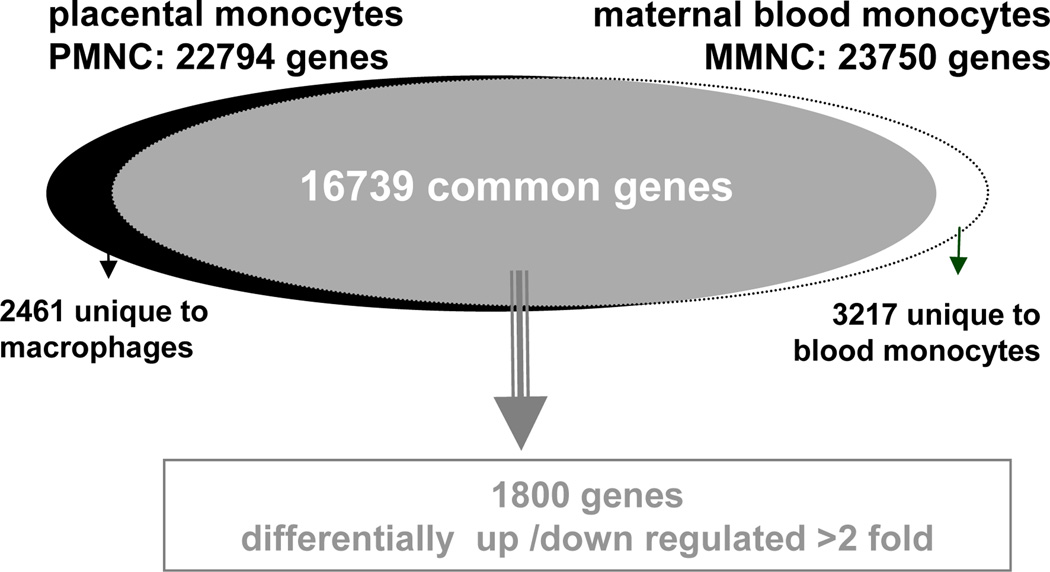

Hybridization of cRNA to HG-U133 plus 2.0 GeneChip pangenomic oligonucleotide arrays containing a total of 47,000 transcripts (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was performed as previously described (6). The raw data files from the Affymetrix arrays were imported into Gene Spring and normalized prior to further analysis. Genes with a FC> 2 were considered differentially expressed between groups. The statistical difference of differential gene expression was estimated by student’s t test and significance analysis of microarray (SAM). 16739 genes were common to the placenta and the maternal blood gene sets, representing 70 and 73 % of their respective transcriptome with 1800 (10 %) differentially expressed (Figure 1). The microarray results were validated by RT-PCR analysis of 18 selected genes using total RNA from 8 individual blood and placental monocyte preparations (Table 2, supplement). Clustering algorithms were used to, evaluate how the various sample groups were derived from principle component analysis (gene GO, St Joseph, MI). Over-represented biological entities were identified within each cluster and annotated with Ontoexpress and gene ontology database (14, 15). Hierarchical clustering was performed with genesis on up-regulated genes to identify most representative group identities (16).

Figure 1. global pattern of gene expression of monocytes from maternal blood and the placenta.

The whole transcriptome of CD14 monocytes from placenta (22794 genes) and maternal blood (23750 genes) was obtained by screening oligonucleotide arrays containing a total of 47,000 transcripts. Filtering of raw data identified 16739 genes common to the 2 data sets. 1800 genes having a false discovery rate <0.05 and a fold change >2 were considered differentially expressed between groups.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as means ± SE. Differences among variables were examined with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significant differences between variables were tested with a Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc test and non parametric McNemar’s test was used for comparing the distribution between gene clusters. The data were analyzed using the Statview II statistical package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Phenotypic characteristics of monocytes

To characterize the populations of monocytic cells present at the maternal-fetal interface, mononuclear cells were isolated from systemic maternal blood and placental tissue of term pregnancy. Women with pre-gravid obesity were selected based on our previous observation that they have chronic low grade inflammation at the systemic with macrophage accumulation in the placenta (6, 12).

Global transcription analysis

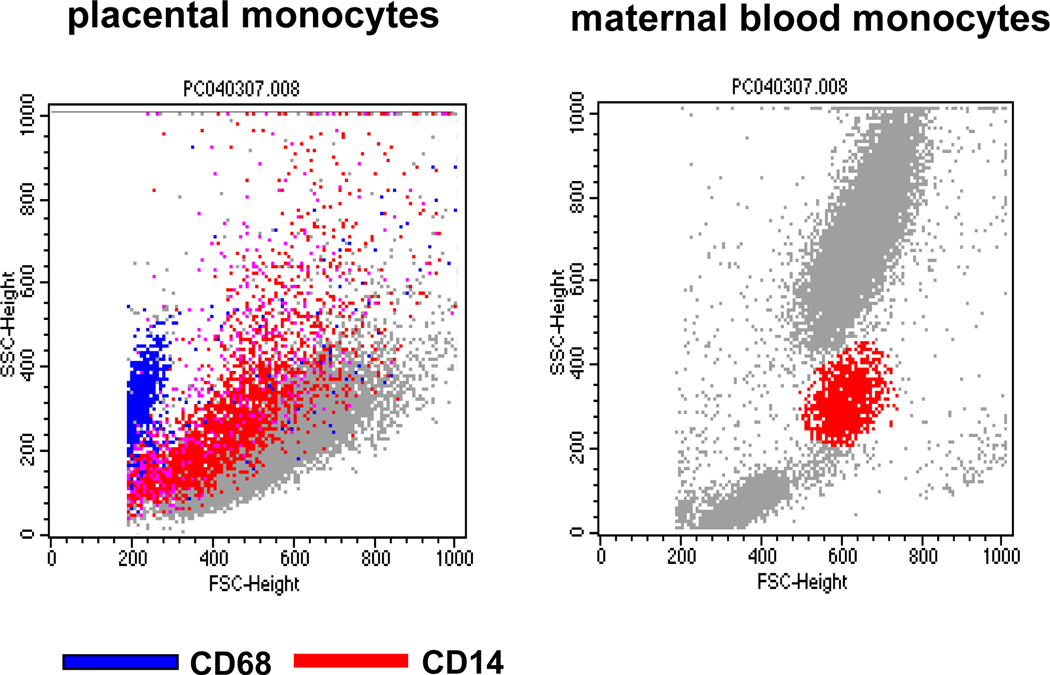

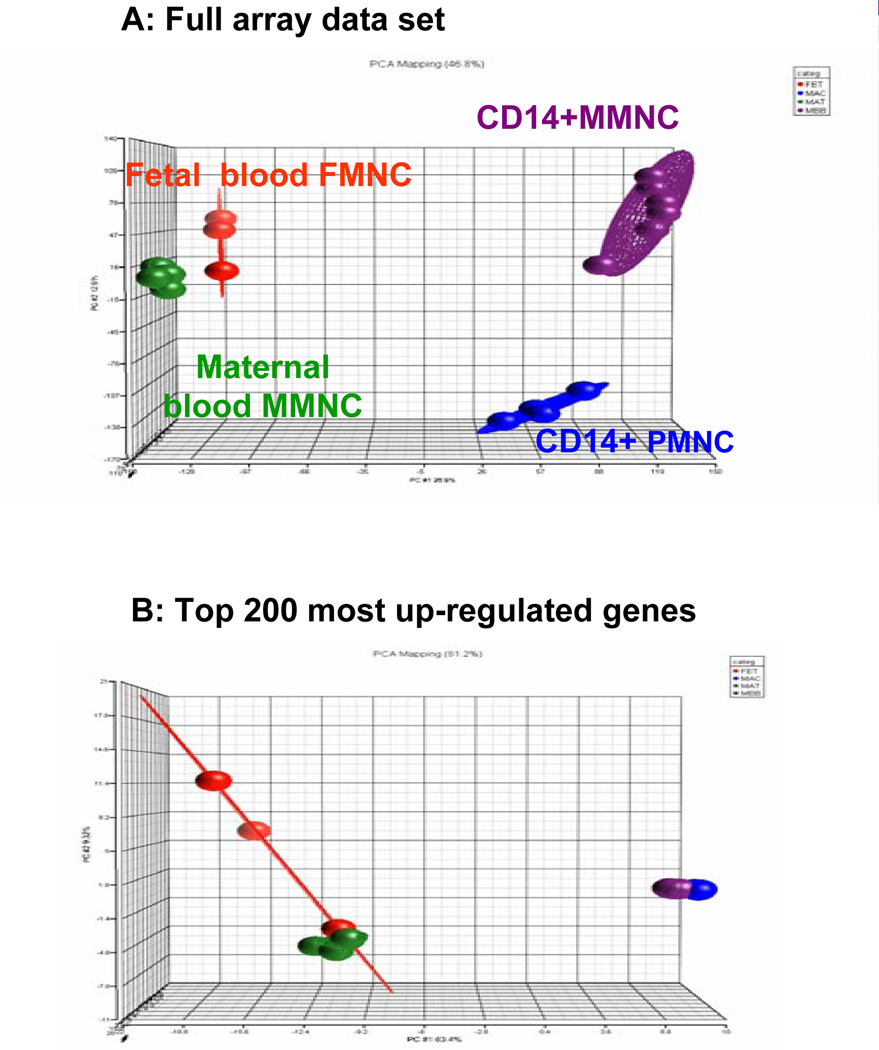

The characteristics of the monocytes isolated from maternal peripheral blood (MMNC) and the placenta (PMNC) were investigated using surface characteristics and oligonucleotide microarrays. Placental cells labeled with the CD14 and CD68 markers for myelomonocytic lineages (9) appeared as a heterogeneous population encompassing a 3-fold greater range in size and distribution as compared to maternal blood monocytes (Figure 2). The global pattern of gene expression of CD14 immuno-selected PMNC and MMNC was compared to that of non immuno-selected MMNC and monocytes from umbilical cord blood. Principal component analysis (PCA) of full genome screen was carried out to identify expression trends within the data set. Analysis of all expressed genes demonstrated that each group of monocytes had a specific pattern of gene expression with 46.8 % of the variance applying to CD14+ cells (Figure 3A). Analysis focused on the 200 most up-regulated genes in the data set revealed a high similarity in gene expression pattern for MMNC and PMNC with 81.2 % of the variance applying to CD14+ cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Flow cytometry analysis of isolated placental and maternal monocytes.

Representative double color fluorescent-activated cell sorter analysis using CD14 - PE and CD68-FITC labeled antibodies. Left panel : dot plot side scattered (SSC) of isolated placental double staining with CD14 and CD68 shows wide distribution and size of CD14 positive cells. Right panel: double staining of maternal mononuclear blood cells. Six cell preparations from independent placentas and blood of women with BMI >25 were analyzed.

Figure 3. principal component analysis (PCA) of the systemic mononuclear cells and placental macrophages.

Three dimensional scatter plots PCA analysis of the transcriptome of CD14 immnuno-selected monocytes from maternal blood (MMNC) and the placenta (PMNC) and non immuno-selected monocytes from maternal and umbilical blood. A: Analysis of full data set shows a segregation pattern between the CD14 immunoselected MMNC and PMNC cells and the non immunoselected cells (mat-MNC and fet-MNC) closely grouped together. B: Analysis of the 200 top regulated genes showed the expression trends in MMNC and PMNC are superimposable. Each knot represents one microarray with a pool of independent cell samples obtained from 4–6 subjects.

Analysis of functional categories

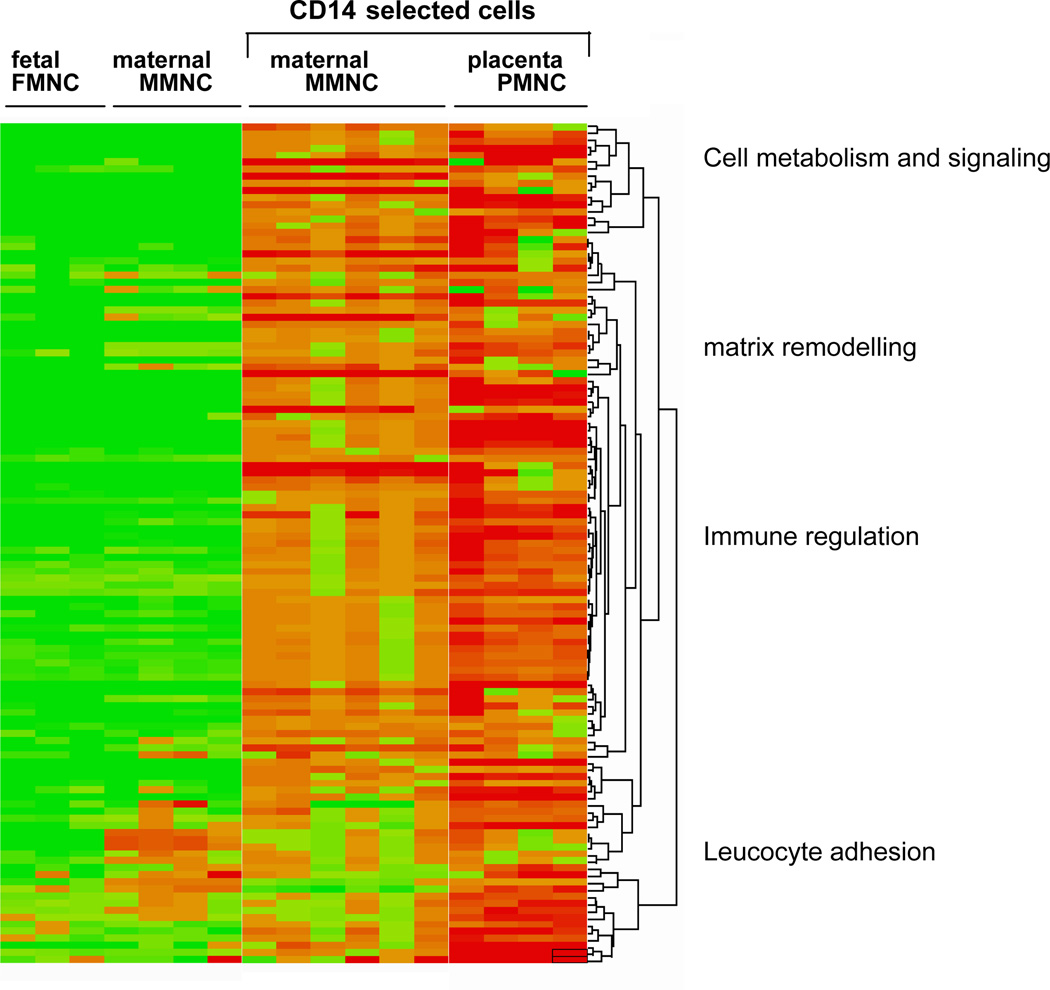

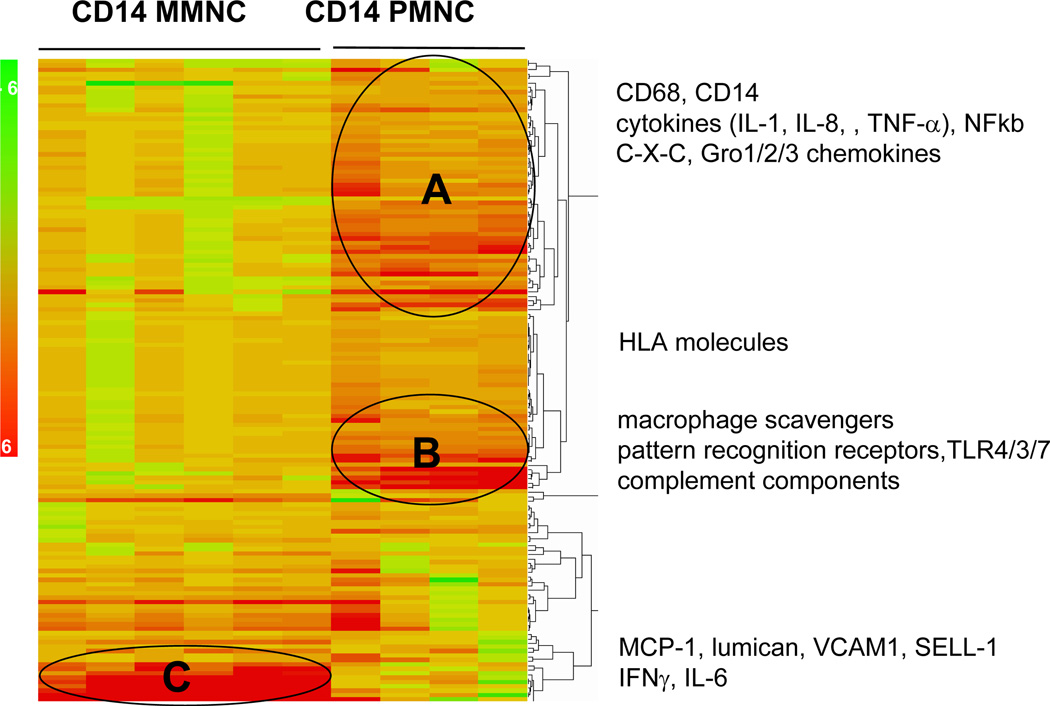

To gain insight into the functional characteristics of the CD14+ cells, the differentially expressed genes were subjected to hierarchical clustering and gene expression ontology. Heat map analysis of the top 200 up-regulated genes selected according to Figure 1 allowed to visualize level of gene expression a 40–2006 (p<0.0001) higher in CD14+ PMNC compared to CD14+ MMNC (Figure 4). The differentially expressed genes segregated into four main biological categories relating to cell metabolism, matrix remodeling, immune regulation, leucocyte chemotaxis (Figure 4). The group of genes classified into immune regulation was subjected to hierarchical sub-cluster to further analyze the biological processes involved in the activation of the monocyte populations (Figure 5, Table 1). The molecular phenotype of PMNC reflected a combination of classic-M1 (cluster A) and adaptive-M2 (cluster B) macrophage subtypes (10) in PMNC. Gene ontology analysis highlighted an overrepresentation of C -C and C-X-C chemokines, IL-8, molecules of the GRO oncogene family and proinflammatory cytokines associated with activation of NF-kappa B signaling pathways in Cluster A while CD36, IL-18, IL- 10 and mannose receptor were prominent in cluster B (Figure 5). By contrast the MMNC had a low expression of macrophage specific molecules but strongly expressed genes related to leucocyte adhesion and chemotaxis, p-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1,VCAM-1, lumican, decorin. Besides the 3 distinct clusters, a number of genes with a 2–4 fold higher expression in PMNC vs MMNC included MHC class II antigens and HLA-DR markers as well as toll-like receptors TLR3, TLR7 and C1, C3 complement component related to recognition and response to pathogens (Table 1).

Figure 4. Hierarchical clustering of the top 200 most induced genes in placental macrophages of obese women.

Clustering generated heat map identified four primary functional clusters based on biological annotation of the genes up-regulated in CD14 immunoselected compared to unselected monocytes cells from maternal and cord blood.

Figure 5. Differential expression of genes regulating immune response in monocytes of maternal blood and the placenta.

GO annotation of immune function and pathways studio significantly up-regulated identified 150 genes based on p values < 10.E−5.

Table 1.

Immune related genes differentially expressed in monocytes of the placenta and maternal blood

| Gene Description | Gene symbol |

Placenta monocytes |

Blood- monocytes |

placenta/Blood ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A | ||||

| nephropontin | SPP1 | 500 | 1 | 500 |

| interleukin 1-alpha | IL1A | 475 | 1 | 475 |

| interleukin 8 | IL-8 | 115 | 1 | 115 |

| mitogen induced nuclear orphan receptor | MINOR | 2006 | 7 | 287 |

| gro-beta | CXCl2 | 276 | 1 | 276 |

| GRO3 oncogene | GRO3 | 182 | 1 | 182 |

| small inducible cytokine B subfamily (C-X-C) | SCYA13 | 41 | 1 | 41 |

| small inducible cytokine subfamily A (C-C) | SCYB13 | 40 | 1 | 40 |

| mannose receptor, C type 1 | MRC1 | 40 | 1 | 40 |

| migration stimulation factor | FN | 35 | 1 | 35 |

| nuclear factor of kappa light enhancer | NFKBIE | 53 | 2 | 27 |

| hyaluronic acid receptor | HAR | 25 | 1 | 25 |

| oncostatin M | OSM | 17 | 1 | 17 |

| interleukin 1-beta | IL1B | 11 | 1 | 11 |

| tumor necrosis factor | TNF12 | 7.5 | 1 | 8 |

| interferon, alpha-inducible protein | G1P3 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | MSR1 | 26 | 4 | 7 |

| TONDU | TONDU | 213 | 34 | 6 |

| TNF8 CD30 ligand | TNF | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| CD68 antigen | CD68 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| CD44 | CD44 | 45 | 10 | 5 |

| macrophage scavenger receptor type III | SR-A | 23 | 5 | 5 |

| MHC class II, DM alpha | MHCDM | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| MHC class II transactivator | MHC2TA | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| epiregulin | EREG | 11 | 3 | 4 |

| complement component 3 | C3 | 294 | 75 | 4 |

| GRO2 oncogene | GRO2 | 261 | 94 | 3 |

| small inducible cytokine subfamily A (C-C) | SCYB20 | 1361 | 1411 | 1 |

| small inducible cytokine subfamily B (C-X-C) | SCYB14 | 41 | 39 | 1 |

| v-jun avian sarcoma virus 17 | JUN | 15 | 15 | 1 |

| fibronectin | HSF1B | 1121 | 1521 | 1 |

| Cluster B | ||||

| small inducible cytokine A3 | SCYA3 | 43 | 1 | 43 |

| small inducible cytokine A4 ( | SCYA4 | 25 | 1 | 25 |

| chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 | CCR5 | 12 | 1 | 12 |

| toll-like receptor 7 | TLR7 | 8 | 1 | 8 |

| thrombospondin receptor 2 | CD36L2 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| thrombospondin receptor 1 | CD36L1 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| scavenger receptor class B | SCARB1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | IRAK1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| MHC class II antigen | HLADRB6 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| MHC class II antigen | HLA-DG | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| matrix metalloproteinase 19 | MMP19 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | MSR1 | 15 | 4 | 4 |

| interleukin 1-beta | IL1B | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| complement component 1, q | C1QA | 170 | 55 | 3 |

| interleukin 18 | IL-18 | 10 | 4 | 3 |

| complement component 1, q | C1QB | 293 | 120 | 2 |

| triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells | TREM2 | 185 | 231 | 1 |

| interleukin 10 | IL-10 | 46 | 117 | 0.4 |

| complement factor H-related 4 | FHR-4 | 1 | 8 | 0.1 |

| Cluster C | ||||

| major histocompatibility complex, | HLA- | |||

| class II | DQA1 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| toll-like receptor 3 | TLR3 | 24 | 3 | 8 |

| interferon-stimulated protein | ISG15 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | VCAM1 | 48 | 20 | 2 |

| monokine induced by gamma | ||||

| interferon | MIG | 102 | 84 | 1 |

| macrophage receptor with collagenous structure | MARCO | 68 | 65 | 1 |

| lumican | LUM | 2476 | 2819 | 1 |

| retinoic acid receptor responder | RARRES1 | 186 | 309 | 1 |

| interleukin 6 | Il-6 | 2802 | 10435 | 0.3 |

| monocyte chemotactic protein 1 | MCP-1 | 116 | 346 | 0.3 |

| complement subcomponent , alpha- and beta | C1s | 294 | 1021 | 0.3 |

| decorin D | DEC | 18 | 100 | 0.2 |

| leukemia inhibitory factor | LIF | 9 | 260 | 0.0 |

List of genes selected based on at least 2-fold difference between the 2 groups. Shown are mean of the expression levels for 6 microarrays. Ratio >1 indicates activation in macrophages and <1 activation in monocytes.

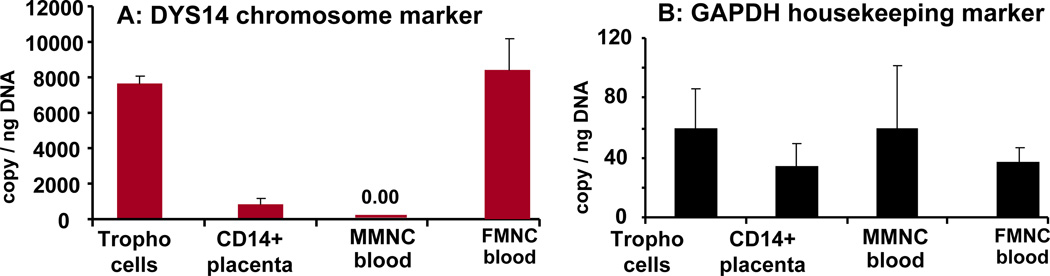

Genotypic characteristics of the monocytes

Based on the fetal (maternal/paternal) genotype of the placenta, cells originating from the placenta of a male fetus can be distinguished from maternal cells on the presence of Y chromosome. DYS14, a marker of the Y chromosome was used to quantitate the number of Y copies in CD14 PMNC. Monocytes from umbilical blood of a male fetus and trophoblast cells isolated from his placenta used as positive control exhibited 101±7 % DYS14 expression. At sharp contrast, the low level of DYS14 expression (9.4 ± 2.4 %) of the CD14 PMNC indicated that the majority of activated monocytes from the placenta were not of fetal lineage (Figure 6).

Figure 6. gender characterization of tissue resident macrophages.

Expression of DYS14 markers for the Y chromosome was quantitated by RT-PCR. PMNC of male fetuses exhibited a low Y copy numbers (p<0.001) compared to cord blood mononuclear cells. The level of Y expression was undetectable in MMNC of maternal blood. The expression of the house keeping gene glyceraldehyde -3-P(GAPDH) is gender independent i.e. same level in maternal and fetal cells. Results are means ± SEM of 6 independent samples from male fetuses with determinations performed in duplicate. All values were normalized for actin.

Discussion

A common monocyte molecular signature in blood and placenta

This study brings to light biological and functional characteristics of the monocytes present at the maternal-fetal interface in term pregnancy of obese women. The close resemblance in the molecular signature of monocytes from maternal blood and the placenta was indicated by the 73% homology of their transcriptome with quantitative rather than qualitative differences. Although both cell types exhibited an inflammatory phenotype the macrophage functionality of the placental cells was suggested by gene expression patterns several order of magnitude higher in placenta than in blood. The second significant findings of our study was that the placental monocytes appeared as an heterogeneous cell population. The immune phenotype of CD14 placental monocytes showed a unique combination of both M1 and M2 subtypes with characteristics of cells transitioning from monocyte to macrophage status (16, 17). This was indicated by differential expression of several cytokines and interferon molecules as well as a panel of chemokines and their receptors (GRO2, GRO3, interleukin-8 and MCP-1 which typically help recruiting cells from the blood to sites of inflammation or tissue repair (18). The increased expression of genes related to lipid, cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism (APOE, APOC1, APO L6) and triglycerides synthesis (Scd, ACSl1, AGPAT9, LPL, PLA2 lipases) involved in lipid loading was another hallmark of macrophage differentiation (19, 20). These molecular traits may reflect the multiples states of differentiation through transitioning from maternal circulation to progressive invasion and homing of the placenta.

Crosstalks at the maternal-fetal interface

Hofbauer cells, have been classically described as the resident macrophages of the human placenta. They are derived from fetal myeloid cells which colonize the villous stroma at very early stages of placental development where they remain throughout the placental lifespan (11, 21). The phenotypic and genotypic similarity of the CD14 systemic and placental cells supports the concept of placental inflammation having a maternal hematogenous initiation (22). However, this concept raises questions relating to the mechanisms allowing maternal systemic monocytes to invade the placenta. The robust activation of extra cellular matrix components and factors involved in leucocyte chemotaxis (decorin, lumican selectin, flaminin, chemokine ligands) in maternal blood monocytes suggested that they are already activated (IL-6) with a potential for transendothelial extravasion.

Enhanced trans-endothelial migration of activated monocytes followed by infiltration into tissues is a feature of the inflammatory response common to all tissues. By contrast, the propagation and the intensity of the response to synthesize cytokines, chemokines and acute phase reactants are specific to each tissue and stimulus (23). Along this line, it has been suggested that signals propagated in the uteroplacental environment may contribute to amplification of inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface through activation and re-programming of maternal monocytes (24).

We found here, that the majority (90%) of the CD14+ monocytes identified in the placenta of obese women with male fetuses were not of fetal lineage suggesting that there is a population of activated placenta which is derived from maternal cells. Several reasons may contribute to the presence of maternal cells in the placenta villous tissue. First, infiltration of maternal cells may be facilitated by the hemochorial structure of the human placenta with maternal blood directly bathing the placenta trophoblast cells without vascular barrier. Second, the outer trophoblast layer is not a strict barrier to infiltration of maternal molecules as previously suggested in pregnancies complicated by villitis (24, 25).

The molecular signature of activated blood and placental monocytes indicates a high potential for immune crosstalks between two cell populations of common origin. Understanding whether the initial stimuli are factors exogenous to maternal environment or signals generated within the placenta will shed more light on the inflammatory mechanisms developing at the maternal-fetal interface

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

NIH RO-1 HD22965, DAGC grant-in-aid 484-04 and ADA1-04-TLG-01. CRU NCRR CTSA UL1 RR 024989

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest

Supplementary data

Table 2: Validation of microarray results by realtime PCR

References

- 1.Renaud SJ, Graham CH. The role of macrophages in utero-placental interactions during normal and pathological pregnancy. Immunol Invest. 2008;37:535–564. doi: 10.1080/08820130802191375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szekeres-Bartho J. Immunological relationship between the mother and the fetus. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21:471–495. doi: 10.1080/08830180215017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, 3rd, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:206–215. doi: 10.1177/1933719108329095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JS, Romero R, Cushenberry E, Kim YM, Erez O, Nien JK, Yoon BH, Espinoza J, Kim CJ, Dennis G. Distribution of CD14+ and CD68+ macrophages in the placental bed and basal plate of women with preeclampsia and preterm labor. Placenta. 2007;5–6:571–576. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challier JC, Bintein T, Basu S, Hotmire K, Minium J, Catalano PM, et al. Obesity in Pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radaelli T, Varastehpour A, Catalano P, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Gestational diabetes induced placental genes for chronic stress and inflammatory pathways. Diabetes. 2003;52:2951–2958. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;14:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeyda M. T M. Stulnig TM Adipose tissue macrophages. Immunology Letters. 2007;112:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez O, Sica FA, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castellucci M, Celona A, Bartels H, Steininger B, Benedetto V, Kaufmann P. Mitosis of the Hofbauer cell: possible implications for a fetal macrophage. Placenta. 1987;8:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(87)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu S, Haghiac M, Surace P, Challier JC, Guerre-Millo M, Singh K, Waters T, Minium J, Presley L, Catalano PM, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Pregravid Obesity Associates With Increased Maternal Endotoxemia and Metabolic Inflammation. Obesity. 2011;19:476–482. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalano PM, Thomas A, Huston-Presley L, Amini SB. Increased fetal adiposity: A very sensitive marker of abnormal in utero development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1698–1704. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khatri P, Bhavsar P, Draghici S. Onto-tools: an ensemble of web-accessible, ontology-based tools for the functional design and interpretation of high-throughout put gene expression experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W449–W456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Nikitin A, Egorov S, Daraselia N, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturn A, Quackenbush J, Trajanoski Z. Genesis: cluster anlysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:207–208.3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Shi B, Huang CC, Eksarko P, Pope RM. Transcriptional diversity during monocyte to macrophage differentiation. Immunol Lett. 2008;117:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker S, Quay J, Koren HS, Haskill JS. Constitutive and stimulated MCP-1, GRO alpha, beta, and gamma expression in human airway epithelium and bronchoalveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L278–L286. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Renier G. Adipocyte-derived lipoprotein lipase induces macrophage activation and monocyte adhesion: role of fatty acids. Obesity. 2007;11:2595–2604. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingman VJ, Cookson KW, Jones CJP, Aplin JD. Characterisation of Hofbauer cells in first and second trimester placenta: incidence, phenotype, survival in vitro and motility. Placenta. 2010;31:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Lloret MI, Winkler-Lowen B, Guilbert LJ. Monocytes adhering by LFA-1 to placental syncytiotrophoblasts induce local apoptosis via release of TNF-alpha. A model for hematogenous initiation of placental inflammations. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:903–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tacke F, Randolph GJ. Migratory fate and differentiation of blood monocyte subsets. Immunobiology. 2006;211:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsey H. McIntire, Karen G Ganacias, Joan S. HuntProgramming of Human Monocytes by the Uteroplacental Environment. Reproductive Sciences. 2008;15:437–438. doi: 10.1177/1933719107314065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redline RW, Patterson P. Villitis of unknown etiology is associated with major infiltration of fetal tissue by maternal inflammatory cells. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:473–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redline RW. Villitis of unknown etiology: non infectious chronic villitis in the placenta. Hum Pathol. 2007;10:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.