Abstract

Background

There has been recent interest in the possibility that epigenetic mechanisms might contribute to the trans-generational transmission of stress-induced vulnerability. Here, we focused on possible paternal transmission using the social defeat stress paradigm.

Methods

Adult male mice exposed to chronic social defeat stress, or control non-defeated mice, were bred with normal female mice and their offspring were assessed behaviorally for depressive- and anxiety-like measures. Plasma levels of corticosterone and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were also assayed. To directly assess the role of epigenetic mechanisms, we used in vitro fertilization (IVF); behavioral assessments were conducted on offspring of mice from IVF-control and IVF-defeated fathers.

Results

We show that both male and female offspring from defeated fathers exhibit increased measures of several depression- and anxiety-like behaviors. The male offspring of defeated fathers also display increased baseline plasma levels of corticosterone and decreased levels of VEGF. However, most of these behavioral changes were not observed when offspring were generated through IVF.

Conclusion

These results suggest that, while behavioral adaptations that occur after chronic social defeat stress can be transmitted from the father to his male and female F1 progeny, only very subtle changes might be transmitted epigenetically under the conditions tested.

Keywords: trans-generational, social defeat, depression, anxiety, In Vitro fertilization

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is among the foremost causes of disability in the world (1). MDD is an extremely common disorder with an overall lifetime risk estimated to be ~15% in the general U.S. population (2). MDD is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. A rich literature has demonstrated that MDD is highly heritable, with roughly 40% of the risk being genetic (3, 4). However, specific causative genes have been difficult to identify with certainty. Environmental factors also contribute importantly. For example, life-time exposure to any of several forms of chronic stress dramatically increases an individual’s risk for MDD(5, 6).

In recent years, there has been increased attention to the possibility that a third mechanism might also contribute to MDD, namely, epigenetics. By definition, epigenetics refers to any changes in organismal or cellular phenotype caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence (genotype). Accordingly, exposure to environmental stress might produce epigenetic alterations (for example, via DNA methylation) in germ cells, which may then affect the phenotype of offspring to influence inherent vulnerability to MDD. Recent insight into this provocative possibility has come from rodent models. Repeated early life stress (maternal separation) has been shown to cause life-long alterations in depression- and anxiety-like behavior and in alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (7). There also is a growing literature that such early life stress increases the vulnerability of offspring of these animals to stress (8, 9). This trans-generational transmission of stress vulnerability seems to be behaviorally transmitted, that is, it is mediated by types of maternal behavior that can pass from one generation to the next. Interestingly, however, a recent study demonstrated that such stress vulnerability might also be transmitted epigenetically by changes in germ cells that subsequently influence the behavior of the offspring for up to 3 generations in a sex-dependent manner (10).

Here, we used the chronic social defeat stress paradigm in adult male mice to further investigate the trans-generational transmission of stress vulnerability, in this case focusing on paternal transmission. We have demonstrated previously that chronic social defeat stress induces several measures of depression- and anxiety-like abnormalities, some of which are very stable and can be reversed by chronic, but not acute, treatment with standard antidepressants (11-14). We studied whether exposure to chronic social defeat stress causes stress-related abnormalities in the F1 offspring of the stressed fathers and whether such transmission might be mediated epigenetically by use of in vitro fertilization (IVF). To further understand a biological mechanism for the transmission of depressive-like behaviors, we examined putative biomarkers of depression in humans, namely, plasma levels of corticosterone and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in offspring of non-defeated and defeated mice (15, 16). Our results demonstrate that, although relatively strong behavioral abnormalities can be transmitted to the next generation, most are not transmitted by IVF, suggesting a limited role for epigenetic mechanisms.

METHODS

Animals

All experimental C57Bl6/J male and female mice (7 weeks) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Retired CD1 breeders used as the aggressors for the social defeat paradigm were obtained from Charles River. All mice were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility on a 12 hour light–dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Social Defeat

Chronic social defeat stress was performed exactly as previously published (11, 13, 14, 17). Briefly, male C57Bl6/J mice were exposed to a novel aggressive CD1 male mouse for 10 min per day, after which the mice were separated by a plexiglass barrier that allows for sensory contact without further physical interaction. Control mice were housed two animals per cage under the same conditions as their experimental counterparts but without the presence of an aggressive CD1 mouse. Twenty-four hours after the last of ten daily defeat or control episodes, the fathers used for all experiments (including IVF) were tested in a social interaction test to assess social avoidance.

Breeding

In the first experiment, male C57Bl6/J mice were subjected to 10 days of social defeat stress and, one month later, were paired, along with control non-defeated mice, with a normal C57Bl6/J female for ten days, at which time the male was removed. In a separate experiment (pre/post offspring study), normal males were bred with a female; the offspring of such pairings were labeled “pre-defeat”. The males were then exposed to 10 days of defeat stress and, one month later, were paired with a female; the offspring of these pairings were labeled “post-defeat”. Because we selected defeated fathers that have a susceptible phenotype, for comparison we also included one generation of offspring of control mice that were not subsequently selected for any depressive traits, therefore representing a random representation of C57 mice. This allowed us to test directly whether the transmission of behavioral abnormalities is a result of any pre-existing (i.e., latent) factors that might exist in this inbred mouse line. As the depressive-like symptoms following social defeat are known to be extremely stable for at least one month (11, 13), all breeding was initiated one month post social defeat stress in order to focus on longer-lasting adaptations. Future experiments are required to learn whether different time points post defeat would result in different findings.

Behavioral testing

Offspring of defeated and non-defeated mice were also tested in a battery of behavioral tests in the following order: elevated-plus-maze, response to novel environment, sucrose preference, and forced swim test. A separate group of mice were not subjected to the forced swim test and instead were studied for their susceptibility to a sub-maximal course of social defeat stress as noted below.

All behavioral tests were carried out as described previously (13, 18). In the elevated plus maze, mice were placed in the center of the maze, and behavior was recorded by videotracking for 5 min under total darkness. Time spent in each zone was analyzed with Ethovision software (Noldus Inc). Responses to a novel environment were measured by placing the mouse in an unfamiliar chamber for 15 min. Locomotor activity was recorded automatically by infrared photobeams. For sucrose preference, animals were acclimated for 3 consecutive days to two-bottle choice conditions (water or 1% sucrose) prior to 3 additional days of choice testing with the position of the tubes interchanged daily. Sucrose preference was calculated as a percentage of sucrose over total liquid consumed and was averaged over the 3 test days. A 1 day forced swim test was conducted for a period of 5 min and latency to immobility was measured.

To assess susceptibility to social defeat stress, we used a sub-maximal defeat paradigm that does not produce social avoidance in control mice but reveals pro-susceptibility factors (13, 19). Mice were exposed to a CD1 aggressor 3 times with 15 min intervals between each exposure. Twenty-four hours later, mice were assessed using the social interaction test.

Neuroendocrine measures

Trunk blood was collected from mice at baseline, or 5 min after 10 min of acute restraint stress, in EDTA lined tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. Plasma was removed and stored frozen (-80°C) until analysis. Levels of corticosterone and of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were measured using commercially available immunoassay kits (Immunodiagnositic Systems and R & D Systems, respectively) according to the manufacturers’ directions. For corticosterone, the intra-assay variability ranged from 3.8%-6.6%, inter-assay variability ranged from 7.5%- 8.6%, and mean assay sensitivity was 0.55 ng/mL. For VEGF, intra-assay variability ranged from 4.3%- 8.4% inter-assay variability ranged from 5.7%-8.4%, and mean assay sensitivity was 3.0 pg/mL. All blood and was collected during the lights on phase between 14:00 and 17:00 hours.

In Vitro Fertilization

We performed IVF as routinely done by Mount Sinai core’s facility using an established protocol for rodent IVF (20). Fresh sperm from either control (non-defeated) or defeated (susceptible) mice, was isolated from the cauda epididymis of behaviorally-tested defeated and non-defeated control males. Bilateral cauda epididymides with several mm of attached vas deferens were isolated into 1 ml of Cook’s Research VitroFert media (K-RVFE-50) in a 35 mm tissue culture dish. Using two 26-gauge tuberculin syringe needles, several cuts were made across the epididymis, and any sperm in the attached vas deferens was pushed out the cut end with the syringes. The dish was placed in a 37°C oven for 10 min to allow the sperm to be released from the cut epididymis into VitroFert media. Using wide-bore pipette tips to prevent damage to the sperm, 20 to 40 mL of the sperm suspension was added to 250 mL drops of VitroFert under mineral oil. One hr later, cumulus masses were isolated from superovulated donor females and placed into the VitroFert drops with the isolated sperm (cumulus masses from 3-5 females were placed into each drop). After 4 to 6 hrs, the oocytes were recovered, washed through 4 changes of FHM media (Millipore/Specialty Media, MR-024-D), and cultured in microdrops of KSOM + amino acid media (Millipore/Specialty Media) overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator. All 2-cell stage embryos were collected and transferred to the oviduct of pseudopregnant females where they develop naturally to term.

Statistics

Two-tailed student t-tests were used to assess social avoidance of the fathers in the social interaction test following chronic social defeat stress. For the susceptibility of offspring to sub-maximal defeat, two-way ANOVA was performed with breeding and submaximal defeat experience as the main factors. In the experiment where mice were bred both before and after defeat stress, statistical calculations were performed using one way ANOVAs to confirm that there were no statistical differences between control and pre-defeat animals. This was then followed by a comparison of the pre-defeat and post-defeat mice using repeated measures ANOVAs with breeding used as the main factor. Each sex was analyzed independently, and followed up using appropriate post hoc tests. For the IVF experiment, planned comparison (t-tests) were used to compare offspring from control and defeated mice derived through IVF. Statistical significance was set to a p value < 0.05.

RESULTS

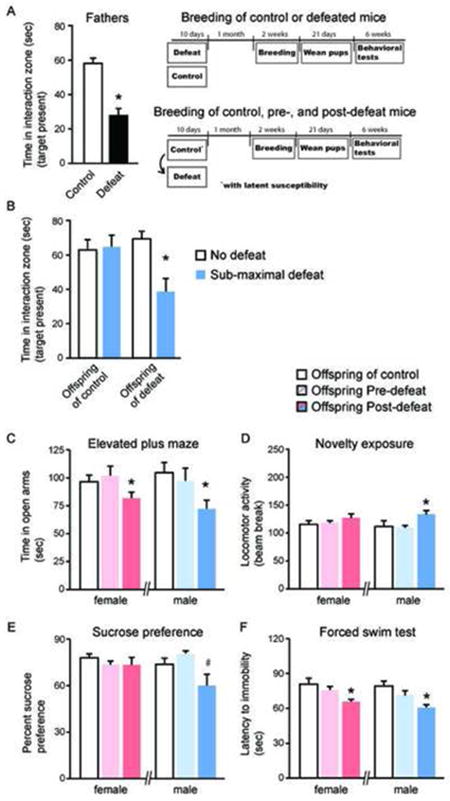

We first tested whether depressive-like behaviors induced in normal male C57Bl6/J mice could be transmitted to their offspring. We used social avoidance as our primary measure, since this has proven to be a highly reliable and long-lived consequence of chronic social defeat stress, which is reversed by chronic (not acute) antidepressant treatment (11-13, 21). As expected, 10 days of chronic social defeat stress induced robust social avoidance when compared to non-defeated control mice (Figure 1A, n=8-9 per group (t=2.229 df=15; *p<0.05). One month later, defeated and non-defeated mice were bred with normal C57Bl6/J female mice. The males were removed shortly after the females became pregnant. The male offspring were then studied, at 8-10 weeks of age, by subjecting them to a sub-maximal defeat paradigm that does not cause social avoidance in control mice but has been validated to reveal pro-susceptibility factors (13, 14). Male mice bred from defeated fathers, but not from control fathers, showed pronounced social avoidance in this paradigm (Figure 1B). Two way ANOVA analysis revealed a main effect (F1,36=8.155; p<0.05), and further Tukey’s Multiple Comparison testing revealed that the source of this effect was the decrease in interaction time of offspring of defeated mice exposed to sub-maximal defeat (p<0.05). Previous work from our laboratory has demonstrated that a proportion (~30%) of chronically defeated mice are resilient to most of the negative behavioral adaptations following defeat, including social avoidance (13). Surprisingly, there was no difference in the susceptibility of the offspring derived from resilient (n=7) or susceptible (n=6) mice, with both showing increased social avoidance to sub-maximal defeat (12.36 ± 5.67 and 15.74 ± 5.169 seconds of interaction time, respectively).

Figure 1. Paternal transmission of stress-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors via natural breeding.

(A) Chronic social defeat induced robust social avoidance in male C57Bl6/J mice compared to control non-defeated mice (*p<0.05). Experimental time line of how these mice were then bred with normal females for behavioral analysis of the offspring. (B) Offspring of socially defeated mice displayed robust social avoidance when exposed to a submaximal defeat paradigm (*p<0.05), which produced no such social avoidance in the offspring of control mice. (C-F) Comparisons of offspring of control mice and offspring from fathers both before undergoing social defeat (pre-defeat) and after undergoing social defeat (post-defeat). (C) Male and female offspring of post-defeat offspring only showed an anxiogenic-like phenotype as measured by an increase in time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (*p<0.05). (D) Only the post-defeat male offspring showed an increase in locomotor behavior in a novel environment (*p<0.05). (E) Likewise, in the sucrose preference test, only the post-defeat male offspring exhibited a trend toward a reduction in sucrose preference (#p<0.07). (F) Both male and female post-defeat offspring showed a decrease in latency to become immobile in the forced swim test (*p<0.05), compared to control and pre-defeat offspring. All values represent means ± standard error of the mean. All (*s) are comparisons of pre- and post-defeat offspring.

To further investigate the role of paternal influence after chronic social defeat stress in depressive- as well as anxiety-like behaviors, we bred male C57BL6/J mice with normal female mice both before and after they were exposed to chronic defeat and later examined a battery of behaviors in the male and female offspring. Non-defeated control mice were also bred. We bred mice prior to social defeat to test the possibility that the increased vulnerability seen in the offspring did not arise from the defeat per se but rather from some pre-existing inherent factors. Unless otherwise noted, these experiments included control bred male mice (n=9), males from pre-defeat fathers (n=12), males from post-defeat fathers (n=12), control bred female mice (n=8), females from pre-defeat fathers (n=17), and females from post-defeat fathers (n=17). In order to compare the pre- and post-defeat animals as non-independent samples, we first confirmed for all behavioral tests, in both male and female mice, that there were no statistical differences between control and pre-defeat offspring (p>0.05 for all comparisons). We then further analyzed offspring from the pre- and post-defeat mice using repeated measures ANOVAs.

We assessed anxiety-like behaviors using two measures, the elevated plus maze and response to novelty. As depicted in Figure 1B, in the elevated plus maze for male offspring, there was a significant main effect of breeding (F 1,11= 14.791; p<0.05). Male offspring from post-defeat fathers spent significantly less time in the open arms in comparison to pre-defeat offspring (*p<0.05). In the case of females there was a significant difference between pre-defeat and post-defeat female offspring (F 1,16= 6.0259; p<0.05), as female offspring from defeated fathers spent significantly less spent in the open arm of the maze compared to pre-defeat offspring (*p<0.05). We next examined the various groups of offspring for their response to novelty (Figure 1D), where increased locomotor activity is taken as a measure of anxiety-like behavior (20). In male offspring there was an overall effect of novelty (F 1,11= 10.275; p<0.05), which was due to an increase in locomotor activity in the offspring of post-defeat fathers (*p<0.05). There was no effect in response to novelty in female offspring (p>0.05).

To test depression-like behaviors, we used the sucrose preference and forced swim tests, two widely used assays for screening depression-like symptoms in rodents (22). In male offspring, there was a strong trend toward a significant effect of breeding in the sucrose preference test (F 1,11= 3.940; p =0.070). In contrast, female offspring showed no effect of breeding condition in this test, with both pre and post-defeat offspring having similar sucrose preferences (p>0.05). In the forced swim test (Figure 1F), we observed a main effect of breeding on latency to immobility in the male offspring (F 1,11=4.939; p<0.05). There was a significant decrease (*p<0.05) in latency in the offspring from post-defeat fathers in comparison to pre-defeat fathers (Figure 1F, *p<0.05). A similar pattern was seen in female offspring (F 1,16=5.680; p<0.5), as again there was a significant decrease in latency to immobility in the offspring from post-defeat fathers when compared to pre-defeat offspring (*p<0.05). Analysis of a separate group of control, pre-defeat, and post-defeat male offspring showed that only post-defeat offspring exhibited the increased susceptibility to sub-maximal defeat, as demonstrated in the initial experiment (Figure 1B).

In still another group of mice generated from pre-defeat and post-defeat fathers, we examined hormonal markers under baseline conditions and in response to acute restraint stress (Table 1). We examined plasma levels of corticosterone, a functional measure of the HPA axis, a well-characterized component of stress responses (23). In males, there was a significant increase in plasma levels of corticosterone under baseline conditions in the post-defeat offspring (n=7) compared to the pre-defeat offspring (n=9) (t=3.513; *p<0.05). However, no difference was observed after exposure to an acute stress (n=6-8). No such differences were observed in the female offspring of pre-defeat and post-defeat fathers. We also examined plasma levels of VEGF, which has been implicated more recently in depression-related rodent models (24, 25). Under baseline conditions, male offspring from post-defeat fathers (n=7) had significantly lower VEGF levels compared to offspring of pre-defeat fathers (n=9) (p<0.05), with no differences seen after acute stress. No difference in VEGF levels was seen in female offspring, although such measurements were highly variable in female mice.

Table 1. Plasma Levels of Corticosterone and VEGF.

Absolute values with the S.E.M. of plasma levels of corticosterone (mg/ml) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (pg/ml) in pre-defeat and post-defeat male and female offspring, both at baseline and following an acute stress. Post-defeat male offspring exhibited an increase in basal corticosterone, and a decrease in basal VEGF, with no differences seen after acute stress. In female offspring, there were no differences in corticosterone or VEGF levels under basal or stressed conditions.

| Male offspring of | Female offspring of | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-defeat | Post-defeat | Pre-defeat | Post-defeat | |

| Corticosterone | ||||

| basal | 10.1 ± 1.64 | 25.3 ± 3.78** | 38.3 ± 7.51 | 48.5 ± 8.16 |

| stressed | 143. ± 0.99 | 162. ± 17.3 | 188. ± 12.6 | 195. ± 5.95 |

| VEGF | ||||

| basal | 4249 ± 6.977 | 4185 ± 22.70 * | 1755. ± 394.3 | 1498. ± 348.3 |

| stressed | 4239. ± 7.030 | 4201. ± 20.24 | 1687.54 ± 512.23 | 988.1 ± 240.2 |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

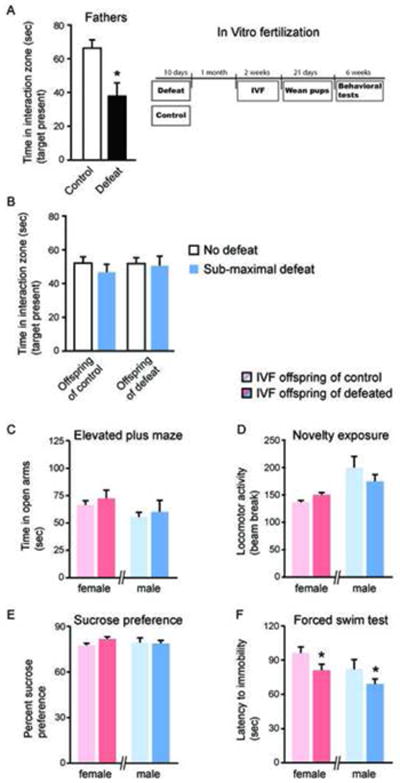

In the final set of experiments, we used IVF to investigate if the behavioral phenotypes observed in the above experiments were directly transmissible through the sperm of socially defeated mice. Sperm from defeated and control mice was used to impregnate normal female mice (Figure 2A). The offspring of these mice were later examined in the same battery of behavioral tests as in our previous experiments. Unlike our previous findings, animals derived using IVF from defeated fathers were not more susceptible to a sub-maximal defeat paradigm compared to IVF control mice and showed no social avoidance (Figure 2B, n=12-18 per group, p>0.05). We also found no significant difference between IVF control and IVF defeated offspring in time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (Figure 2C, p>0.05). There was a trend toward increased locomotor activity in a novel environment in the IVF defeated compared to IVF control female offspring (p=0.06), however, no difference was apparent in the male offspring (Figure 2D, p>0.05). In the sucrose preference test, there was no effect when comparing IVF control to IVF defeated offspring of either sex (Figure 2E). Importantly, in the forced swim test, we found that both male (t=1.876 df=33; *p<0.05) and female (t=1.752 df=28; *p<0.05) IVF defeated offspring exhibited a small, but significant decrease in latency to immobility compared to IVF control mice (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Paternal transmission of stress-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors via IVF.

(A) Chronic social defeat stress induced robust social avoidance in male C57Bl6/J mice compared to control non-defeated mice (*p<0.05). Experimental time line including IVF and subsequent behavioral experiments. (B) Offspring derived from defeated or control fathers using IVF showed no social avoidance following a sub-maximal defeat paradigm. (C) IVF defeated male and female offspring did not differ in time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze compared to IVF control offspring. (D) There was a trend for increased locomotor activity in a novel environment in female IVF defeated offspring compared to female IVF control offspring (p=0.06), but no difference in males. (E) There was no difference in sucrose preference in either male or female IVF defeated offspring compared to IVF control offspring. (F) In comparison to IVF control offspring, both male and female IVF defeated offspring showed a small but significant decrease in latency to become immobile in the forced swim test (*p<0.05). All values represent means ± standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that key aspects of both depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors can be transmitted to the offspring of socially defeated fathers. While abnormalities were observed in both male and female offspring of stressed fathers, in general, a more robust phenotype was seen in the male offspring. The fact that such behavioral abnormalities were seen only in offspring bred after the fathers experienced defeat, and not before, indicates that the vulnerability being transmitted is a direct effect of the stress and not caused by some pre-existing diathesis. The male offspring of defeated fathers also exhibited a significant disturbance in neuroendocrine signaling, specifically, increased plasma levels of corticosterone and decreased levels of VEGF. These differences were observed at baseline with no differences seen after an acute stress. Altered plasma levels of these two hormones are consistent with previous reports implicating corticosterone and VEGF in both depressive-like phenotypes and the efficacy of antidepressant treatment (23-25). Interestingly, despite the fact that social defeat induces two-distinct behavioral phenotypes, susceptible and resilient mice (13), offspring of these mice are equally vulnerable. This raises the intriguing question of the shared mechanism for this transmission. Of interest, we have previously demonstrated that resilient mice, although by definition do not display depressive-like features, do display increased anxiety-like behavior comparable to that seen in susceptible individuals (13). This heightened anxiety may affect the care given by the mother to the progeny. However, further work is needed to explore this possibility. Additionally, because of the timing of breeding for the pre-post experiment, we cannot definitively rule out that the behavioral abnormalities observed may be due to prior mating experience or age-dependent effects on gamete development. However, given our original observations in which similar differences were obtained in offspring of control and of defeated mice of the same age and sexual experience, we believe that these caveats are not a major contributor to the behavior observations.

The trans-generational transmission of stress vulnerability traits in offspring of socially defeated mice implicates a role for epigenetic modifications in the paternal germ line. Indeed, a recent study reported the trans-generational transmission of stress vulnerability, induced by maternal separation, a form of early-life stress, that is mediated through the male germ line (10). This study related such trans-generational transmission to altered DNA methylation at CpG islands of the MeCP2 (methylated CpG binding protein 2), CB1 (cannabinoid receptor 2), and CRFR2 (corticotropin release factor receptor 2) genes in the sperm of early-life stressed males (10). These provocative findings suggest that environmental perturbations can lead not only to life-long behavioral adaptations for the individuals who experience such challenges (8, 9), but may also alter behavioral responses of future generations who were not directly exposed to the traumas per se (10).

However, our data argue for more complex explanations, at least with respect to social defeat stress experienced during adulthood. The fact that most of the trans-generational transmission of stress vulnerability observed in our experiments was not seen with IVF argues against the preponderance of epigenetic mechanisms. Rather, our data would suggest that the bulk of the vulnerabilities are passed on to subsequent generations behaviorally, presumably on the basis of the female detecting that she had procreated with an impaired male. Indeed, female rodents are known to adjust their reproductive investment depending on the interaction that they had with the male (26). The exact mechanism behind such behavioral adaptations in the case of our results remains hypothetical. For example, precopulatory, copulatory, or postcopulatory behavior of defeated male might cause increased female stress perhaps via direct physical aggression/interaction, pheromonal signaling, or ultrasonic vocalization, which could conceivably indicate inferiority or a degree of unfitness. It should also be noted that the process of IVF itself has several caveats that need to be considered. The IVF process may select sperm that are in different stages of maturation, which may have a direct impact on the level of genomic imprinting (27). Therefore, the lack of transmission of robust disease traits in our experiments might reflect epigenetic erasure. Moreover, IVF generated offspring did show statistically significant behavioral abnormalities, albeit far more subtle and limited than those observed with natural procreation, suggestive of a limited influence of true epigenetic mechanisms.

In summary, we have demonstrated the transmissibility of both depressive- and anxiety-like phenotypes to the F1 generation in male, and to a lesser extent in female, offspring of socially defeated male mice. Future studies are needed to examine if these behavioral phenotypes are passed to subsequent generations (e.g., F2), as recent studies have demonstrated for early life stress, which can be transmitted several generations in a sex-dependent manner (10). Although our IVF experiments indicate that most of the trans-generationally transmitted behavioral phenotypes likely occur through behavioral mechanisms, a small role for epigenetic modifications is apparent, which now requires genome-wide assessments of chromatin changes in sperm of socially defeated mice and the elaboration of how any such changes observed lead to differences in neurobiology and behavior in the offspring.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant award from the National Institutes of Health P50 MH66172 to EJN.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Dietz, Dr. LaPlant, Ms. Watts, Dr. Hodes, Dr. Russo, Dr. Feng, Dr. Oosting, Dr. Vialou, and Dr. Nestler report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:386–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Verdeli H, Pilowsky DJ, et al. Families at high and low risk for depression: a 3-generation study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.aan het Rot M, PhD, Mathew SJ, MD, Charney DS., MD Neurobiological mechanisms in major depressive disorder. CMAJ. 2009;180:305–313. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meaney MJ. Maternal Care, Gene Expression, and the Transmission of Individual Differences in Stress Reactivity Across Generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ. Nongenomic Transmission Across Generations of Maternal Behavior and Stress Responses in the Rat. Science. 1999;286:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin TB, Russig H, Weiss IC, Gräff J, Linder N, Michalon A, et al. Epigenetic Transmission of the Impact of Early Stress Across Generations. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covington HE, Maze I, LaPlant QC, Vialou VF, Ohnishi YN, Berton O, et al. Antidepressant Actions of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:11451–11460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1758-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vialou V, Robison AJ, Laplant QC, Covington HE, 3rd, Dietz DM, Ohnishi YN, et al. DeltaFosB in brain reward circuits mediates resilience to stress and antidepressant responses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:745–752. doi: 10.1038/nn.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dome P, Teleki Z, Rihmer Z, Peter L, Dobos J, Kenessey I, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and depression: a possible novel link between heart and soul. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;14:523–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachar EJ, Hellman L, Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. Cortisol Production in Depressive Illness: A Clinical and Biochemical Clarification. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1970;23:289–298. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01750040001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson MB, Xiao G, Kumar A, LaPlant Q, Renthal W, Sikder D, et al. Imipramine Treatment and Resiliency Exhibit Similar Chromatin Regulation in the Mouse Nucleus Accumbens in Depression Models. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:7820–7832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0932-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vialou V, Maze I, Renthal W, LaPlant QC, Watts EL, Mouzon E, et al. Serum Response Factor Promotes Resilience to Chronic Social Stress through the Induction of ŒîFosB. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:14585–14592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2496-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaPlant Q, Vialou V, Covington HE, Dumitriu D, Feng J, Warren BL, et al. Dnmt3a regulates emotional behavior and spine plasticity in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1137–1143. doi: 10.1038/nn.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley KA. Enhancement of IVF in the Mouse by Zona-Drilling. In: Paul MW, Philippe MS, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 229–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nn1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Kloet ER. Hormones and the Stressed Brain. Annals of the NewYork Academy of Sciences. 2004;1018:1–15. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. VEGF as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in depression. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2008;8:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene J, Banasr M, Lee B, Warner-Schmidt J, Duman RS. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling is Required for the Behavioral Actions of Antidepressant Treatment: Pharmacological and Cellular Characterization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2459–2468. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curley JP, Mashoodh R, Champagne FA. Epigenetics and the origins of paternal effects. Hormones and Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.06.018. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Inoue K, Ono R, Ogonuki N, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, et al. Erasing genomic imprinting memory in mouse clone embryos produced from day 11.5 primordial germ cells. Development. 2002;129:1807–1817. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]