Abstract

Context

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience increased rates of hospitalization and death. Depressive disorders are associated with morbidity and mortality. Whether depression contributes to poor outcomes in patients with CKD not receiving dialysis is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether the presence of a current major depressive episode (MDE) is associated with poorer outcomes in patients with CKD.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Prospective cohort study of 267 consecutively recruited outpatients with CKD (stages 2–5 and who were not receiving dialysis) at a VA medical center between May 2005 and November 2006 and followed up for 1 year. An MDE was diagnosed by blinded personnel using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was event-free survival defined as the composite of death, dialysis initiation, or hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included each of these events assessed separately.

Results

Among 267 patients, 56 had a current MDE (21%) and 211 did not (79%). There were 127 composite events, 116 hospitalizations, 38 dialysis initiations, and 18 deaths. Events occurred more often in patients with an MDE compared with those without an MDE (61% vs 44%, respectively, P=.03). Four patients with missing dates of hospitalization were excluded from survival analyses. The mean (SD) time to the composite event was 206.5 (19.8) days (95% CI, 167.7–245.3 days) for those with an MDE compared with 273.3 (8.5) days (95% CI, 256.6–290.0 days) for those without an MDE (P=.003). The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the composite event for patients with an MDE was 1.86 (95% CI, 1.23–2.84). An MDE at baseline independently predicted progression to dialysis (HR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.77–6.97) and hospitalization (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.23–2.95).

Conclusion

The presence of an MDE was associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes in CKD patients who were not receiving dialysis, independent of comorbidities and kidney disease severity.

Depression is associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes1–3 and is found to be prevalent in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), affecting up to 20% of patients even before initiation of dialysis.4 Approximately 13% of the US adult population has CKD, and it is well recognized as an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.5–7 Moreover, those with CKD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than to progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8 Patients who survive to progress to ESRD experience a mortality rate of 21% in their first year of dialysis6 compared with 0.5% for the general US population,9 with cardiovascular disease accounting for 50% of all deaths.6 In addition, increased hospitalizations and dialysis care for ESRD patients result in substantial health care costs, such that expenditures consumed $24 billion in 2007, approximately 6% of the entire Medicare budget.6

Previous studies have identified depression as an independent risk factor for hospitalization and death in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.10–13 However, studies investigating the clinical outcomes of patients with earlier-stage CKD and depression prior to progression to ESRD and dialysis initiation are lacking. Because processes of care for patients with CKD are predictive of clinical outcomes in those with ESRD, better recognition of disease processes, such as depression, which portend morbidity and mortality, could lead to improved treatment outcomes for such patients.14,15 A cohort of patients with CKD not yet started on maintenance dialysis was prospectively studied to determine whether there was an association between a current major depressive episode (MDE), based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria,16 and progression to dialysis, hospitalization, or death during 1 year of follow-up.

METHODS

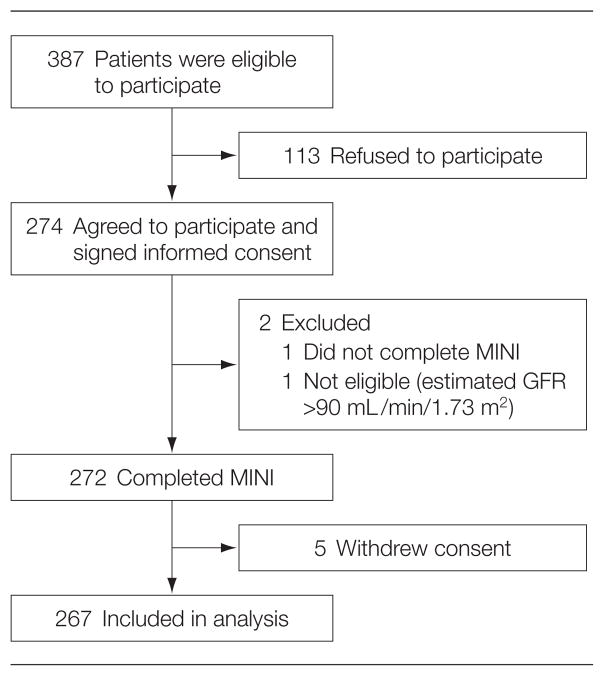

Patients were recruited consecutively from the Dallas VA Medical Center between May 2005 and November 2006 (Figure 1). The study was approved by the VA institutional review board. Informed written consent was obtained by study personnel prior to patient enrollment. Inclusion criteria were presence of CKD (stages 2–5), defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months, using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.17 Patients with stage 2 CKD (estimated GFR of 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2) had to have other evidence manifest by either a pathological abnormality of the kidney on biopsy or markers of kidney damage present for at least 3 months.5 Exclusion criteria were initiation of maintenance dialysis or kidney transplantation and no health care power of attorney.

Figure 1.

Description of Chronic Kidney Disease Cohort

GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

Detailed methods of recruitment were previously published.4 Prior to each clinic visit, the CKD clinic roster was reviewed to identify patients for screening. The VA electronic centralized patient record system was then searched for eligibility criteria. Due to the large numbers of patients with CKD, all eligible patients could not be approached on any 1 clinic day. Therefore, every sixth eligible patient (starting at a random number between 1 and 6 for each specific clinic day) was approached consecutively to minimize selection bias.

All patients underwent a structured interview at enrollment to ascertain the presence of an MDE using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, a widely used reliable and well-validated interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).18,19 The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, which takes 30 to 45 minutes to complete, was administered by 1 of 2 trained research assistants blinded to patients’ medical histories. Those with a current MDE were categorized as depressed, while those without one were deemed not depressed. If a current MDE was diagnosed, both the patient and their primary care provider were informed. The patient also was offered either treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or an increase in dose if he or she was already receiving treatment with an antidepressant medication.

Demographic and baseline clinical data were collected from the centralized patient record system and confirmed with patients at enrollment. Race/ethnicity was recorded based on self-report and then dichotomized as black or nonblack for the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease calculation of estimated GFR. Comorbid medical illness was defined as presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, lung disease, liver disease, malignancy other than on skin, and infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Comorbid psychiatric illnesses other than depression ascertained by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview included dysthymia, current or past manic or hypomanic episode, current panic episode, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, current psychotic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Current or past drug or alcohol abuse collected from the centralized patient record system or the patient was coded as drug or alcohol abuse.

Patients were followed up for 1 year from MDE ascertainment. The primary outcome formulated before data collection was event-free survival defined as the composite of death, maintenance dialysis initiation, and first hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were the occurrence of each of these 3 events assessed individually. Event ascertainment was performed on the same patient by 2 adjudicators blinded to baseline MDE status. Data on death, hospitalizations, and initiation of renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplantation) were collected at 6 and 12 months and were confirmed with the patient. Events were first determined by searching the VA centralized patient record system. Each patient was then contacted to determine whether any events had occurred outside the VA medical center; these data were collected from the discharge summary obtained from the institution where the event occurred.

Demographic and clinical data were compared between the 2 groups (with an MDE vs without an MDE) using the t test or 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The proportion of composite events was compared among groups using the χ2 test. Time to events was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared among groups using the log-rank statistic. Censorship took place at the first event, last follow-up, or if the patient had no events at 12 months. If event date was missing, the patient was excluded from the analysis for that specific event. Cox proportional hazards models were used to explore the association of an MDE with the primary composite and each of the secondary end points. Assuming an α level of .05 and an event rate between 40% and 50% (as reported by the US Renal Data System for CKD patients6), a sample size of 208 to 260 patients was needed to have 85% power to detect an 80% increase in the hazard of the composite outcome among CKD patients with an MDE compared with those without an MDE.

Independent covariates were entered into multivariable models only if clinically relevant and significantly associated with the outcome measure in univariate analyses; a retention P value of less than .05 was determined a priori. Candidate variables included age, race, employment status, drug or alcohol abuse, number of medical comorbidities (other than diabetes), diabetes mellitus, CKD stage, and serum levels of hemoglobin, albumin, phosphorus, and calcium. Chronic kidney disease stage was replaced by estimated GFR as a measure of kidney disease severity in the models with dialysis as the outcome, given there were not enough events to include the 4 categories of CKD. Complete case analysis was used when data were missing for included covariates. A sensitivity analysis was performed by entering new treatment for an MDE into the multivariable Cox model as an independent variable to investigate whether treatment was associated with a change in the composite outcome. New treatment was defined as the initiation of treatment with an antidepressant medication or increasing the dose of a previously prescribed antidepressant within 3 weeks of an MDE diagnosis. All statistical tests were 2-sided, conducted at the standard significance level of .05, and reported using P values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide software versions 3.0 and 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of participants and nonparticipants, such as sex, race, CKD stage, presence of diabetes, and prior depression diagnosis were similar. However, mean (SD) age was 64.5 (12.0) years among participants and 68.8 (11.0) years among nonparticipants (P=.001; 95% CI for the difference, −6.9 to −1.8 years). Two patients in this VA cohort were women and more than half of the patients were white. About half of the patients had diabetes and a fourth had a prior depression diagnosis. Among participants, the prevalences were 6.4% for CKD stage 2, 37.8% for stage 3, 41.2% for stage 4, and 14.6% for predialysis stage 5. Nonparticipants had similar prevalences for the CKD stages.

Of 267 participants, 56 had a current MDE (21%; 95% CI, 3% to 31%) and 211 did not (Table 1). The MDE group was younger based on a mean (SD) age of 60.6 (11.9) years compared with the group without an MDE (mean [SD], 65.4 [11.8] years; P = .007; 95% CI for the difference, −8.3 to −1.3 years). There were no significant between-group differences in regard to race, educational level, or marital status. Patients with an MDE, however, were two-thirds less likely to be employed as those without an MDE. The median number of medical comorbidities was 4.0 (inter-quartile range, 2.0 to 5.0) among those with an MDE and 3.0 (inter-quartile range, 2.0 to 4.0) among those without an MDE. Diabetes mellitus was significantly more prevalent among those with an MDE (69.6%) compared with those without an MDE (51.9%; P=.02; 95% CI for the difference, 4% to 32%). More patients with an MDE had histories of drug or alcohol abuse and concurrent psychiatric disorders. Sixty-six percent of those with an MDE had prior depression vs 13.6% of those without an MDE (95% CI for the difference, 39% to 66%; P < .001); and 50.0% with an MDE vs 11.9% without an MDE were taking antidepressant medications (95% CI for the difference, 24% to 52%; P < .001). Twenty-three of 56 patients (41%) agreed to have a new antidepressant prescribed or the dose of their current antidepressant increased at the time of MDE diagnosis (defined as new treatment).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Depression Statusa

| Not Depressed (n = 211) | Depressed (n = 56)b | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.4 (11.8) | 60.6 (11.9) | .007 | |

|

| ||||

| No. (%) | ||||

| Female sex | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.8) | .38 | |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 121 (57.4) | 30 (53.6) |

|

.86 |

|

| ||||

| Black | 77 (36.5) | 22 (39.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Otherc | 13 (6.2) | 4 (7.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Education >high school | 125 (60.1) | 30 (56.6) | .64 | |

|

| ||||

| Married | 141 (67.1) | 38 (67.9) | .92 | |

|

| ||||

| Employed | 47 (22.5) | 4 (7.1) | .008 | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease by stage | ||||

| 2 | 13 (6.2) | 4 (7.1) |

|

.980 |

|

| ||||

| 3 | 82 (38.9) | 19 (33.9) | ||

|

| ||||

| 4 | 86 (40.8) | 24 (42.9) | ||

|

| ||||

| 5 | 30 (14.2) | 9 (16.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 109 (51.9) | 39 (69.6) | .02 | |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension | 204 (96.7) | 55 (98.2) | >.99 | |

|

| ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 79 (37.8) | 25 (44.6) | .35 | |

|

| ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 61 (29.9) | 16 (29.1) | .90 | |

|

| ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 48 (23.7) | 15 (27.3) | .58 | |

|

| ||||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 46 (22.2) | 7 (12.5) | .12 | |

|

| ||||

| History of nonskin cancer | 34 (16.4) | 7 (12.5) | .47 | |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid medical illnessd | 82 (38.9) | 29 (51.8) | .08 | |

|

| ||||

| History of drug or alcohol abuse | 55 (26.3) | 24 (42.9) | .02 | |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid psychiatric illnesse | 12 (5.7) | 25 (44.6) | <.001 | |

|

| ||||

| History of depressionf | 28 (13.6) | 37 (66.1) | <.001 | |

|

| ||||

| Antidepressant medication use | 25 (11.9) | 28 (50.0) | <.001 | |

|

| ||||

| No. of comorbidities | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.5) | .12 | |

|

| ||||

| Median (range) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | .09 | |

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.5 (1.9) | 12.4 (2.2) | .89 | |

|

| ||||

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.7) | .97 | |

|

| ||||

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 3.9 (1.0) | 4.2 (1.1) | .04 | |

|

| ||||

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.3 (0.6) | 9.3 (0.8) | .83 | |

|

| ||||

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.6) | .69 | |

|

| ||||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 3.2 (2.4) | 3.3 (2.4) | .75 | |

|

| ||||

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 42.2 (20.0) | 42.1 (22.9) | .97 | |

|

| ||||

| Estimated GFR, mL/min | 31.6 (16.2) | 31.3 (18.6) | .91 | |

Abbreviation: GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

SI conversion factors: To convert albumin to g/L, multiply by 10; blood urea nitrogen to mmol/L, multiply by 0.357; calcium to mmol/L, multiply by 0.25; creatinine to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4; GFR to mL/s, multiply by 0.017; hemoglobin to g/L, multiply by 10; potassium to mmol/L, multiply by 1.0; phosphorus to mmol/L, multiply by 0.323.

Some of the percentages do not sum to 100 because the denominator did not include the number missing for those variables.

Patients were given the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and received a diagnosis of current major depressive episode.

Other indicates Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Alaska native, and Pacific Islander.

Indicates presence of 4 or more medical comorbidities in addition to chronic kidney disease.

Indicates at least 1 psychiatric illness other than depression or drug or alcohol abuse.

As documented in the medical records.

The only difference between groups for laboratory values was for mean (SD) serum phosphorus level, which was higher in those with an MDE (4.2 [1.1]) compared with those without an MDE (3.9 [1.0]) (P=.04; 95% CI for the difference, 0.02 to 0.63; Table 1). There was not a difference between groups in the proportion of patients by CKD stage.

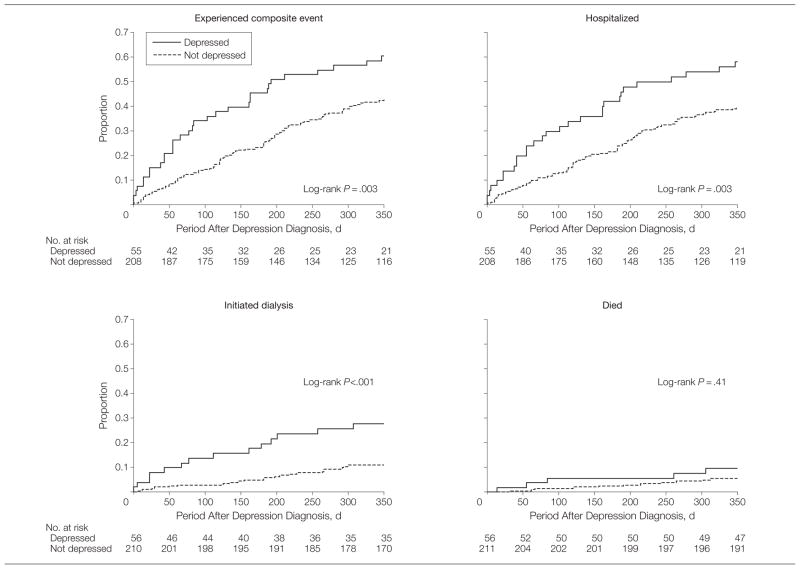

During the 12-month observation period, 127 patients had at least 1 composite event (death, hospitalization, or maintenance dialysis initiation). More patients with an MDE had at least 1 event (60.7%) compared with those without an MDE (44.1%) (P = .03; 95% CI for the difference, 2%–31%; Table 2). The mean (SD) time to the composite event was 260.2 (8.1) days (95% CI, 259.2–261.2 days) overall, and was shorter for those with an MDE (206.5 [19.8] days; 95% CI, 167.7–245.3 days) compared with those without an MDE (273.3 [8.5] days; 95% CI, 256.6–290.0 days) (log-rank P =.003; Figure 2). Four patients were excluded from the survival analysis because the date for the first event (hospitalization in each of these cases) was missing. Of the 4 patients, 1 had an MDE and 3 did not have an MDE.

Table 2.

Events by Depression Status

| Event | Total | No. (%) of Patients | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Depressed (n = 211) | Depressed (n = 56)a | ||||

| Composite eventb | 127 | 93 (44.1) | 34 (60.7) | .03 | |

| Any hospitalizations | 116 | 85 (40.3) | 31 (55.4) | .04 | |

| Cardiovascularc | 21 | 17 (20.0) | 4 (12.9) |

|

.14d |

| Dialysis initiation | 16 | 9 (10.6) | 7 (22.6) | ||

| Infection | 8 | 4 (4.7) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| Dialysis access-related | 8 | 5 (5.9) | 3 (9.7) | ||

| Depression | 1 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | ||

| Other | 52 | 42 (49.4) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| Missing discharge diagnosis | 10 | 7 (8.2) | 3 (9.7) | ||

| Maintenance dialysis initiation | 38 | 23 (10.9) | 15 (26.8) | .003 | |

| Hemodialysis | 36 | 22 (95.7) | 14 (93.3) |

|

>.99e |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 2 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Death | 18 | 13 (6.2) | 5 (8.9) | .55 | |

Patients were given the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and received a diagnosis of current major depressive episode.

Indicates hospitalization, dialysis initiation, or death.

Indicates any hospitalization due to acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or stroke.

P value for trend based on the Fisher exact test.

P value based on the Fisher exact test.

Figure 2.

Survival Curves for Outcome Measures

The composite event is defined as death, hospitalization, or maintenance dialysis initiation. Four patients with missing dates of hospitalization were excluded from the composite event and hospitalization models. One patient with missing event date was excluded from the dialysis model.

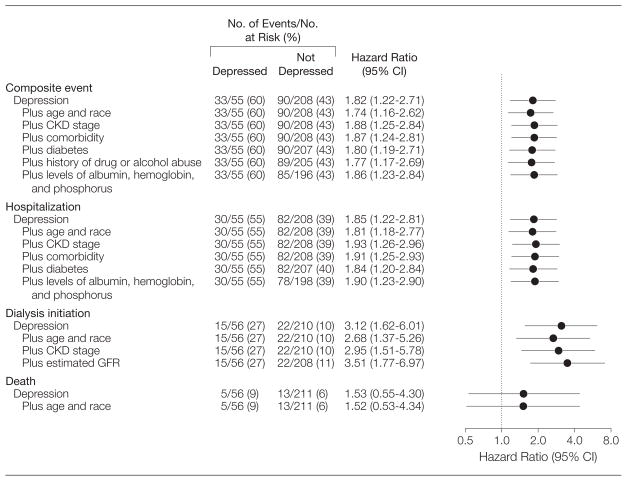

Those with an MDE had a higher risk of death, hospitalization, or maintenance dialysis initiation within 12 months of MDE diagnosis compared with those without an MDE (hazard ratio [HR], 1.82 [95% CI, 1.22–2.71]; Figure 3). Variables associated with the composite event in univariate analyses included younger age, white race, higher CKD stage, medical comorbidity, diabetes mellitus, drug or alcohol abuse, lower serum albumin and hemoglobin levels, and higher serum phosphorus levels (data not shown). After adjusting for these covariates, the adjusted HR for the composite outcome was not diminished and remained significant (1.86 [95% CI, 1.23–2.84]; Figure 3). Inclusion of new treatment for an MDE was not significantly associated with the composite outcome in the adjusted model (HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.48–2.30]; P=.90), and it did not significantly change the hazard of an MDE for the composite outcome (adjusted HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.14–2.96).

Figure 3.

Adjusted Risks of Events Associated With Major Depressive Episode

CI indicates confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

One hundred sixteen were hospitalized, 38 initiated maintenance dialysis, and 18 died (Table 2). More patients with an MDE compared with those without an MDE were hospitalized (55.4% vs 40.3%, respectively, P=.04; [95% CI for the difference, 0.5% to 29.7%]), but no statistically significant differences in reasons for hospitalization could be observed (Table 2). More patients with an MDE were initiated on maintenance dialysis compared with those without an MDE (26.8% vs 10.9%, respectively, P=.003; [95% CI for the difference, 3.6% to 28.2%]; Table 2). Death occurred in 8.9% of those with an MDE and in 6.2% of those without an MDE, but this difference was not statistically significant (95% CI for the difference, −5.4% to 10.8%) (Table 2).

Patients with CKD and an MDE had almost twice the risk of being hospitalized (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.22–2.81), and 3 times the risk of initiating dialysis within 1 year (HR, 3.12 [95% CI, 1.62–6.01]; Figure 3). After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, the association of having an MDE with both hospitalization (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.23–2.90) and dialysis initiation (HR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.77–6.97) remained significant (Figure 3). The HR of death for patients with an MDE was 1.53 (95% CI, 0.55–4.30).

COMMENT

The new finding in this prospective study of consecutively enrolled patients with CKD is that the presence of an MDE ascertained by an interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition)16 predicts progression to maintenance dialysis, hospitalization, or death within 1 year of depression diagnosis. This is the first report, to our knowledge, of such an association in CKD patients prior to maintenance dialysis initiation. Patients with CKD and an MDE were twice as likely to be admitted to the hospital and more than 3 times as likely to progress to ESRD and maintenance dialysis initiation as patients without an MDE. This increased risk was robust and independent of age, race, and presence of diabetes or other medical comorbidities, and remained significant even after controlling for other markers of disease progression such as CKD stage, serum levels of hemoglobin, albumin, and phosphorus.

Most10–13,20–27 but not all28,29 of the studies of ESRD patients receiving maintenance dialysis reported an association between depressive symptoms and poor outcomes. Study limitations included small samples, retrospective design, selection bias, lack of control for comorbidity,11–13,20–29 and depression ascertainment using self-report measures.12,13,20,22,29 Such measures may misclassify loss of energy, sleep disturbance, and poor appetite as symptoms of depression in those with advanced CKD.30–32 We previously validated the use of easily administered self-report scales, such as the Beck Depression Inventory and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report, in this same cohort of pre-dialysis CKD patients compared with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for depression screening.33 In the present study, diagnosis of an MDE was ascertained blindly using a psychiatric interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition),16 not self-report of depressive symptoms. Finally, we studied CKD patients with earlier stages of disease, prior to ESRD. Twenty-six million individuals in the United States have CKD and millions more are at increased risk,34 whereas about half a million are affected by ESRD.35

A key question is whether depression itself has a direct mechanistic role in the development of morbidity and mortality in CKD or whether depressive symptoms are merely a surrogate marker for comorbidity and cardiovascular disease severity.10 We found that inclusion of comorbidity and other risk factors does not attenuate the association between depression and poor outcomes.

Plausible mechanisms to explain this association include nonadherence to medical advice, such as to diet and fluid intake as observed in hemodialysis patients with increased depressive symptoms.36–39 Decreased behavioral adherence is consequently associated with decreased survival.40 A recent large study41 reported increased depressive symptoms in patients being treated for diabetes. In our study, a significantly higher number of patients with an MDE had diabetes compared with those without an MDE. Those with diabetes and depression may develop progressive nephropathy due to nonadherence and are at a higher risk for hospitalization and death due to diabetic complications. Other mechanisms may include poor nutrition, lack of social support, increased inflammation, and compromised immunity.42–46 Altered serotonin levels observed in depressed patients with ensuing platelet activation leading to coronary events has also been proposed.47,48 Treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor compared with placebo after diagnosis of an acute coronary syndrome was associated with reductions in platelet activation and a trend toward improved cardiovascular outcomes in the Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial.47–49

Our study has several limitations. First, patients were primarily male veterans, which may limit generalizability to the US population with CKD. However, studies of ESRD patients that included a large proportion of women have demonstrated a similar relationship between depression and outcomes.10,12,13,50 Second, given that the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease estimating equation for GFR is imprecise above the range in which it was derived,17 it is possible that those with an estimated GFR greater than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 may have been mis-classified as having CKD. To minimize this bias, patients with an estimated GFR of 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 included in our analysis were required to also have other evidence of kidney disease manifest by either pathological abnormalities on kidney biopsy or other markers of kidney damage present for at least 3 months.5 A third but unavoidable limitation is the exclusion of those who refused participation. In addition, patients with more advanced CKD or other conditions prompting more frequent physician visits would be more likely to be recruited. We tried to minimize these potential biases by approaching patients consecutively for enrollment. Baseline characteristics of participants and nonparticipants were similar except that participants were younger. Because worse outcomes were found in patients with an MDE, who were also younger than patients without an MDE, it is unlikely that the inclusion of older nonparticipants would have biased the results toward the null. Another limitation is that the time-varying covariates were not adjusted for, although, survival models did control for baseline variables. Finally, the statistically significant associations between the presence of an MDE and poor outcomes was primarily due to increased rates of hospitalizations and dialysis initiation, and the event rate may have been too small to detect a significant association between having an MDE and death if one did exist.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the presence of a current MDE was associated with progression to maintenance dialysis, hospitalization, or death in CKD patients, independent of comorbidities and kidney disease severity. The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression if practices “have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up.”51 Our findings support the need for randomized controlled trials to investigate the safety and efficacy of antidepressant treatments in this vulnerable population, and to establish whether a positive effect on depression will improve renal outcomes and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants from the Veterans Integrated Systems Network 17 and the VA North Texas Health Care System Research Corporation, which were used for the design and conduct of the study and collection, management, and analysis of data; and grant P30DK079328 to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center O’Brien Kidney Research Core Center (pilot and feasibility awarded to Susan Hedayati, MD), which was used for the analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript. This work also was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2K24DK002818-0 (awarded to Robert Toto, MD), which was used for the preparation and review of the manuscript. Support for Dr Rush was provided by the Rosewood Corporation Chair in Biomedical Science.

Role of the Sponsor: None of the funding agencies had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Previous Presentation: The results of this study were presented in abstract form at the American Society of Nephrology 41st Annual Meeting; November 8, 2008; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Author Contributions: Dr Hedayati had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Hedayati, Toto, Trivedi, Rush.

Acquisition of data: Hedayati, Afshar.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Hedayati, Minhajuddin, Toto, Trivedi, Rush.

Drafting of the manuscript: Hedayati, Afshar.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hedayati, Minhajuddin, Toto, Trivedi, Rush.

Statistical analysis: Minhajuddin, Hedayati.

Obtaining funding: Hedayati.

Study supervision: Hedayati, Toto, Trivedi.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Rush reported receiving consulting fees from Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, AstraZeneca, Best Practice Project Management, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Cyberonics, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Gerson Lehrman Group, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Magellan Health Services, Merck & Company, Neuronetics, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Organon, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Urban Institute, and Wyeth Ayerst; speaking fees from Cyberonics Inc, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Otsuka; royalties from Guilford Publications and Healthcare Technology Systems; and research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. He also reported owning shares of stock in Pfizer.

References

- 1.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction: impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993;270(15):1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariyo AA, Haan M, Tangen CM, et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Depressive symptoms and risks of coronary heart disease and mortality in elderly Americans. Circulation. 2000;102(15):1773–1779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, Morris DW, Rush AJ. Prevalence of major depressive episode in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(3):424–432. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 suppl 1):S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(12 suppl):S16–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedayati SS, Bosworth H, Briley L, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74(7):930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedayati SS, Grambow SC, Szczech LA, Stechuchak KM, Allen AS, Bosworth HB. Physician-diagnosed depression as a correlate of hospitalizations in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):642–649. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57(5):2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, et al. Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62(1):199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renal Physicians Association. Appropriate Preparation of the Patient for Renal Replacement Therapy, Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 3. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2002. pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen WF., Jr Patterns of care for patients with chronic kidney disease in the United States: dying for improvement. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(7 suppl 2):S76–S80. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070145.00225.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):232–241. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einwohner R, Bernardini J, Fried L, Piraino B. The effect of depressive symptoms on survival in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(3):256–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmermann PR, Camey SA, Mari Jde. A cohort study to assess the impact of depression on patients with kidney disease. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(4):457–468. doi: 10.2190/H8L6-0016-U636-8512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troidle L, Watnick S, Wuerth DB, Gorban-Brennan N, Kliger AS, Finkelstein FO. Depression and its association with peritonitis in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(2):350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Early death in dialysis patients: risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(10):2169–2175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shulman R, Price JDE, Spinelli J. Biopsychosocial aspects of long-term survival on end-stage renal failure therapy. Psychol Med. 1989;19(4):945–954. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wai L, Richmond J, Burton H, Lindsay RM. Influence of psychosocial factors on survival of home dialysis patients. Lancet. 1981;2(8256):1155–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burton HJ, Kline SA, Lindsay RM, Heidenheim AP. The relationship of depression to survival in chronic renal failure. Psychosom Med. 1986;48(3–4):261–269. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drayer RA, Piraino B, Reynolds CF, III, et al. Characteristics of depression in hemodialysis patients: symptoms, quality of life, and mortality risk. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(4):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devins GM, Mann J, Mandin H, et al. Psychosocial predictors of survival in end-stage renal disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(2):127–133. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen AJ, Wiebe JS, Smith TW, Turner CW. Predictors of survival among hemodialysis patients: effects of perceived family support. Health Psychol. 1994;13(6):521–525. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69(9):1662–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA. Depression in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: tools, correlates, outcomes, and needs. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(4):741–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, Morris DW, Rush AJ. Validation of depression screening scales in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54 (3):433–439. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Kidney Foundation. [Accessibility verified April 14, 2010.];The facts about chronic kidney disease (CKD) http://www.kidney.org/kidneydisease/ckd/index.cfm.

- 35.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2008 Annual Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1818–1823. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Everett KD, Brantley PJ, Sletten C, Jones GN, McKnight GT. The relation of stress and depression to interdialytic weight gain in hemodialysis patients. Behav Med. 1995;21(1):25–30. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safdar N, Baakza H, Kumar H, Naqvi SA. Non-compliance to diet and fluid restrictions in haemodialysis patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 1995;45(11):293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sensky T, Leger C, Gilmour S. Psychosocial and cognitive factors associated with adherence to dietary and fluid restriction regimens by people on chronic haemodialysis. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65 (1):36–42. doi: 10.1159/000289029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Psychosocial factors, behavioral compliance and survival in urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54(1):245–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friend R, Hatchett L, Wadhwa NK, Suh H. Serum albumin and depression in end-stage renal disease. Adv Perit Dial. 1997;13:155–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koo JR, Yoon JW, Kim SG, et al. Association of depression with malnutrition in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(5):1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonnet F, Irving K, Terra JL, Nony P, Berthezène F, Moulin P. Anxiety and depression are associated with unhealthy lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178(2):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barefoot JC, Burg MM, Carney RM, et al. Aspects of social support associated with depression at hospitalization and follow-up assessment among cardiac patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23(6):404–412. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Empana JP, Sykes DH, Luc G, et al. Contributions of depressive mood and circulating inflammatory markers to coronary heart disease in healthy European men: the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME) Circulation. 2005;111(18):2299–2305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164203.54111.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, et al. Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial Study Group. Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation. 2003;108(8):939–944. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085163.21752.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, et al. Enhanced platelet/endothelial activation in depressed patients with acute coronary syndromes: evidence from recent clinical trials. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003;14(6):563–567. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHEART) Group. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288(6):701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boulware LE, Liu Y, Fink NE, et al. Temporal relation among depression symptoms, cardiovascular disease events, and mortality in end-stage renal disease: contribution of reverse causality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(3):496–504. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larkin M. Depression screening may be warranted for adults, says US task force. Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1836. [Google Scholar]