Abstract

A concise, stereocontrolled synthesis of the citrinadin B core architecture from scalemic, readily available starting materials is disclosed. Highlights include ready access to both cyclic tryptophan tautomer and TRANS-2,6-disubstituted piperidine fragments, an efficient, stereoretentive mixed Claisen acylation for the coupling of these halves, and further diastereoselective carbonyl addition and oxidative rearrangement for assembly of the core.

In complex, small molecule synthesis, the adoption of reagent- or substrate-directed strategies to achieve stereocontrol – or a combination thereof – depends on the particular challenges posed by the synthesis target of interest. In the case of citrinadin B1 (1, Figure 1) – a scarce, cytotoxic, marine meroterpene alkaloid – the density of stereocenters in the center of the molecule would seem to favor a strategy wherein a merger of prefabricated, scalemic fragments would permit the management of remote stereochemical relationships. The central cyclopentane has four fully substituted carbon atoms, three of which are centers of asymmetry. However, the establishment of such stereocenters by enantioselective methods lags behind those methods that set tertiary carbon stereocenters,2 and pre-existing elements of complexity may render predictions of stereochemical course difficult. In contrast, the advantages of relative stereocontrol mentioned above might be realized in the context of a synthesis of citrinadin B core architecture; the successful implementation of this strategy is reported herein.3

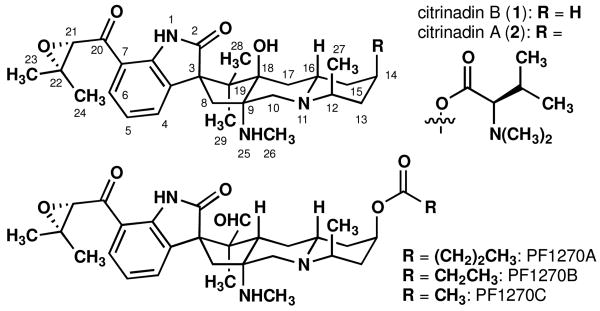

Figure 1.

Structures of the citrinadins and PF1270A–C.

The citrinadins1,4 (1 and 2) and PF1270A– PF1270C5,6 (see Figure 1) comprise a tryptophan portion, a piperidine fragment, and two isoprene units, one bonded peripherally to C7 (heterocycle numbering) of the oxindole, whereas the other is deeply embedded such that a carbon-carbon bond is expressed to all three central carbons of this isoprene unit. As the isoprene units are small, their installation allows for considerable flexibility. In contrast, we opted to commence with tryptophan and piperidine fragments and find suitable means for their stereocontrolled synthesis and union.

The utility of cyclic tautomers of tryptophan7,8 in stereoselective synthesis of amino acid derivatives has been studied.9,10 Chain-to-ring tautomerism gives structures with a pronounced folded topology; in the wake of enolization events, trappings with electrophiles would occur on the convex face of the molecule.11,12 We relied on this propensity to stereoselectively join two halves of roughly equal complexity. Subsequent chemo- and/or diastereoselective transformations were then used to complete a synthesis of the citrinadin B core.

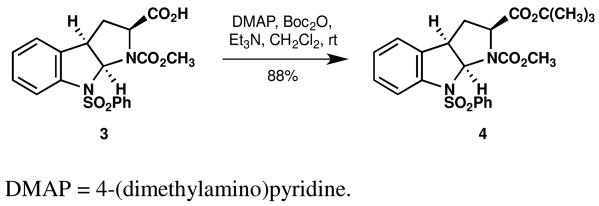

Readily available acid 313 is esterified in good yield though the intermediacy of an in situ-generated mixed carbonate, giving tert-butyl ester 4 (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of tert-butyl ester 4.

The piperidine portion (see Scheme 2) is generated in scalemic form starting with a classical resolution of (±)-2-methylpiperidine.14 Neutralization/carbamoylation then gives N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-(R)-2-methylpiperidine (5). This material is alkylated stereoselectively by modifying conditions originally reported by Beak and coworkers.15 In particular, transmetallation to a Cu(I) salt promotes efficient carbon-carbon bond formation and suppresses by-product formation with allyl bromide as electrophile; strict temperature control is required for desirable diastereoselectivity favoring piperidine 6.16 Two-step oxidative cleavage by initial dihydroxylation with substoichiometric OsO4 and 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane using K3Fe(CN)6 as terminal oxidant followed by cleavage with substoichiometric RuCl3 and excess NaIO4 furnishes acid 7. At this point, electrophile 8 is formed by simple dehydrative esterification of acid 7 with di-iso-propylcarbodiimide and pentafluorophenol.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of ester 8.

The fragment union is accomplished by the following sequence: (1) initial enolization of a slight excess of tert-butyl ester 4 using lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide in cold THF; (2) subsequent addition of hexamethylphosphoramide; (3) addition by cannula of a cold solution of pentafluorophenyl ester 8; and (4) cold-temperature quench with acetic acid (see Scheme 3).17 The delayed addition of hexamethylphosphoramide minimizes deprotonation at the benzylic site of the ester 4 (i.e. “lateral” deprotonation) found to occur in optimization studies of this reaction. This mixed Claisen acylation generates β-keto ester 9 in 77% isolated yield and with high diastereoselectivity. The greatest erosion of diastereoselectivity arises if the reaction mixture is not quenched cold with glacial acetic acid, which leads to epimerization at C16 (citrinadin B numbering), ostensibly by a β-elimination–1,4-addition mechanism.

Scheme 3.

Toward citrinadin B: attainment of the core architecture.

Compound 9 is converted to β-keto lactam 10 by a three stage process wherein: (1) the Boc group is selectively removed using in situ-generated HCl; (2) after evaporation to dryness of the methanolic mixture, the resultant residue is taken up in anhydrous toluene, treated with excess POCl3, and the mixture heated at reflux; (3) the resultant mixture is evaporated to dryness, dissolved in neat TFA, and stirred for two days.10 After neutralization, workup, and flash column chromatography, lactam 10 is obtained in 59% overall yield from β-keto ester 9. This sequence of operations constitutes a refined process for lactamization and ring-to-chain tautomerism as the pyrroloindoline topology of 4 is superfluous after fragment coupling and the original indole structure must be restored. Numerous other methods for unimolecular amide bond formation were surveyed, but provided inferior results on scale due to the propensity of the intermediate β-keto acid to undergo decarboxylation, a process driven by favorable entropic gains and release of strain. The use of POCl3 directly on a tert-butyl ester of type 9 had two-fold motivation: (1) the interaction between the ester carbonyl and oxophilic POCl3 might induce ionization of the tert-butyl group, rendering a separate hydrolysis step unnecessary and (2) the resulting acyl phosphate intermediate might mimic the reactivity seen with the intermediates invoked in phosphonium-based amide bond-forming reactions;18 neutralization of the secondary amine would then lead to spontaneous lactamization. In practice, cyclization occurs spontaneously without exogenous base during treatment with POCl3 in boiling toluene. The reaction mixture that results contains mostly the ring tautomer of 10; this material is easily converted to 10 as described above.

The remaining three carbon atoms of the central isoprene unit and another fully substituted stereocenter are incorporated by a diastereoselective carbonyl addition of iso-propenylmagnesium bromide to the ketocarbonyl of lactam 10. Predictably higher diastereoselectivity is observed with lower reaction temperatures (10:1 at −78 °C). There are two noteworthy aspects of this outcome. First, in a control experiment, the cyclic tautomer of 10 furnished no products of ketocarbonyl addition, providing circumstantial evidence for a directed process19,20 when chain tautomer 10 is subjected to the reaction conditions. Second, although no affirming correlations could be discerned in the NOESY spectrum of carbinol 11, its C18 epimer (citrinadin B numbering; see structure SI-3 in the Supporting Information) bore a correlation between both termini of the isopropenyl group and C16–H, thus establishing structure 11 by a process of elimination.

Although citrinadin B has a central cyclopentane core, we addressed this element indirectly by oxidative rearrangement of a 2,3-disubstituted indole to a 3,3-disubstituted oxindole for two reasons: first, given the high density of fully substituted carbons, it seemed logical to rearrange hindered, pre-existing bonds rather than attempting to generate such bonds to already-crowded centers directly; second, the factors giving rise to diastereoselection during oxidative rearrangement appeared predictable and possibly amenable to substrate control. Thus, carbinol 11 is reductively deprotected with Mg powder in methanol buffered with solid NH4Cl furnishing a free indole that readily undergoes a formal cycloisomerization with a slight excess of Hg(O2CCF3)2 followed by reductive demercuration of the resultant C– Hg σ-bond. Pentacycle 12 is isolated in 90% overall yield starting from pure carbinol 11. Notably, the use of mixtures of 11 and its carbinol epimer at C18 is of no consequence since only the desired, predominant diastereomer undergoes mercurative cyclization.

Earlier investigations pointed to a protecting group liability during attempted oxidative rearrangement. Though the details are beyond the scope of this Letter, NMR and MS data suggest azetidine or cyclic imidate products from such reactions when the N25 atom or a carbamate group bonded to it have any appreciable nucleophilicity. The electrophilicity at C3 of indole during pinacol-like rearrangement may thus be diverted at the expense of oxindole formation. To address this difficulty, a protecting group exchange of carbamate for azide is performed. The methyl carbamate-protected nitrogen of 12 is deprotected with remarkable chemoselectivity with excess BBr3·S(CH3)2 at ambient temperature, furnishing amine 13 in 96% isolated yield, and this material is converted to azido amine 14 by a two step sequence involving reduction of the lactam function by sodium bis(2-methoxyethoxy)aluminum hydride and conversion of the primary amine to an azide upon treatment with trifluoromethanesulfonyl azide.21 Finally, carbamoylation of the indole nitrogen occurs upon treatment with stoichiometric 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine and excess di-tert-butyl dicarbonate at 55 °C furnishing azido carbamate 15 in 47% isolated yield.

The desired oxidative rearrangement22,23 was achieved by sequential treatment of azido carbamate 15 with: (1) a slight excess of trifluoroacetic acid to protonate and therefore protect the tertiary amine from oxidation; (2) at least three equivalents of anhydrous, exogenously-generated trifluoroperacetic acid;24 and (3) ten equivalents of dimethyl sulfide to quench unconsumed oxidant. After neutralization, workup, and purification, oxindole 16 is isolated in 33% yield. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture reveals that the desired product is the predominant species (see Supporting Information); the identity of the remaining products, however, remains to be determined. The refined protocol for oxidative rearrangement was identified based on previously observed complications, and the finding that trifluoroperacetic acid is uniquely effective at converting carbamate 15 to oxindole 16. This oxidant was chosen not only because other, less electrophilic peracids were found to be incapable of oxidation of the Boc-protected indole nucleus but also because the heightened acidity of this reagent might enable a substrate-directable chemical reaction wherein the tertiary hydroxyl group serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor, as opposed to a donor as seen with other hydroxyl-directed epoxidations.25 Although this hypothesis served as a design element, more rigorous studies are required before such a conclusion can be firmly established. Nonetheless, the production of oxindole 16 demonstrates that the highly substituted, stereochemically rich core of citrinadin B is accessible via oxidative rearrangement of a 2,3-disubstituted indole.

The chemistry described herein serves as a milestone in our effort to synthesize citrinadin B.26 Apart from the brevity and operational simplicity of our route, other points of note include: (1) utilization of the stereochemistry of L-tryptophan in an overall “self-reproduction of chirality” event; (2) ready access to scalemic piperidine fragment 8; (3) an efficient mixed Claisen acylation union; (4) designed, diastereoselective carbonyl addition and oxidative rearrangement reactions to address remaining problems of stereocontrol in the citrinadin B context. These investigations place the projected completion of our synthesis on a firm foundation, and may allow more general questions to be answered with regard to the physiological performance of this potential anti-leukemic agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM065483 to E.J.S.; F32-GM086035 to C.A.G.).27 We thank Drs. István Pelczer and John Eng (both of Princeton University) for spectroscopic assistance. Graham Hone (Princeton University) is acknowledged for reproduction of experimental procedures.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Detailed experimental procedures, characterization data, and spectra of isolated and purified intermediates are provided free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mugishima T, Tsuda M, Kasai Y, Ishiyama H, Fukushi E, Kawabata J, Watanabe M, Akao K, Kobayashi J. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9430–9435. doi: 10.1021/jo051499o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Liao X, Stanley LM, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2088. doi: 10.1021/ja110215b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Douglas CJ, Overman LE. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) The 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognized enantioselective hydrogenation and oxidation reactions, yet the former obviously cannot be used for the establishment of quaternary stereocenters starting from π-systems.

- 3.For a previous report from our laboratory directed toward the citrinadin B structure, see: Chandler BD, Roland JT, Li Y, Sorensen E. J Org Lett. 2010;12:2746. doi: 10.1021/ol100845z.

- 4.Tsuda M, Kasai Y, Komatsu K, Sone T, Tanaka M, Mikami Y, Kobayashi J. Org Lett. 2004;6:3087. doi: 10.1021/ol048900y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushida N, Watanabe N, Okuda T, Yokoyama F, Gyobu Y, Yaguchi T. J Antiobiot. 2007;60:667. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Kushida N, Watanabe N, Yaguchi T, Yokoyama F, Tsujiuchi G, Okuda T. Novel Physiologically Active Substances PF1270A, B and C. 1612273. Eur Pat Appl. 2004; (b) Kushida N, Watanabe N, Yaguchi T, Yokoyama F, Tsujiuchi G, Okuda T. U. S. Patent 7,501,431. 2009 March 3;

- 7.(a) Ohno M, Spande TF, Witkop B. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:6521. doi: 10.1021/ja01025a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ohno M, Spande TF, Witkop B. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:343. doi: 10.1021/ja00705a643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hino T, Taniguchi M. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:5564. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hino T, Nakagawa M. Chemistry and Reactions of Cyclic Tautomers of Tryptamines and Tryptophans. In: Brossi A, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 34. Academic Press, Inc.; San Diego; 1988. pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crich D, Banerjee A. Acc Chem Res. 1997;40:151. doi: 10.1021/ar050175j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crich D, Davies JW. Chem Commun. 1989:1418. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crich D, Bruncko M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6251. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prepared by saponification of the corresponding methyl ester. See Supporting Information for experimental procedure. The starting methyl ester has been reported (formerly available from Aldrich); see: Chan CO, Crich D, Natarajan N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:3405.

- 14.Craig JC, Pinder AR. J Org Chem. 1971;36:3648. [Google Scholar]; A modified procedure was employed, the details of which are provided in the Supporting Information.

- 15.(a) Beak P, Lee WK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:1187. [Google Scholar]; (b) Beak P, Lee WK. J Org Chem. 1993;58:1109. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieter RK, Oba G, Chandupatla KR, Topping CM, Lu K, Watson RT. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3076. doi: 10.1021/jo035845i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For a similar strategic union via mixed Claisen acylation see: Vaswani RG, Chamberlin AR. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1661. doi: 10.1021/jo702329z.

- 18.Coste J, Frérot E, Jouin P. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2437. [Google Scholar]

- 19.For an authoritative review of directed reactions see: Hoveyda AH, Evans DA, Fu GC. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1307.

- 20.Paquette has reported similar directivity: Hilmey DG, Galluci JC, Paquette LA. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:11000.

- 21.Vasella A, Witzig C, Chiara JL, Martin-Lomas M. Helv Chim Acta. 1991;74:2073. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin disclosed a similar oxidative ring contraction strategy toward citrinadin A: Pettersson M, Knueppel D, Martin SF. Org Lett. 2007;9:4623. doi: 10.1021/ol702132v.

- 23.Both Martin's our own work were based on Foote's observation that indoles bearing electron withdrawing groups at N1 rearrange to oxindoles spontaneously upon epoxidation in contrast to ring opening to C3-hydroxyindolenines when the indole is unprotected: Zhang X, Foote CS. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8867.

- 24.Generation of solutions of trifluoroperacetic acid: Ballini R, Marcantoni E, Petrini M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4835.

- 25.McKittrick BA, Ganem B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:4895. [Google Scholar]

- 26.For recent disclosures from other groups: McIver AL, Deiters A. Org Lett. 2010;6:1288. doi: 10.1021/ol100177u. (b) At the 2011 Grasmere Heterocyclic and Synthesis Symposium (May 5–9, 2011) Prof. Stephen Martin presented a lecture describing his laboratory's synthesis of the penacyclic core structure of citrinadin B. Kong K, Smith GM, Wood JL. Progress Towards the Total Synthesis of Citrinadins A & B. 42nd National Organic Symposium; June 6–9, 2011; Princeton, NJ.

- 27.Research toward a synthesis of citrinadin B was conducted by C.A.G. from February 2009 to April 2011

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.