Abstract

Acute poisoning with various substance is common everywhere. The earlier the initial resuscitations, gastric decontamination and use of specific antidotes, the better the outcome. The aim of this study was to characterize the poisoning cases admitted to the tertiary care hospital, Warangal district, Andhra Pradesh, Southern India. All cases admitted to the emergency department of the hospital between the months of January and December, 2007, were evaluated retrospectively. We reviewed data obtained from the hospital medical records and included the following factors: socio-demographic characteristics, agents and route of intake and time of admission of the poisoned patients. During the outbreak in 2007, 2,226 patients were admitted to the hospital with different poisonings; the overall case fatality rate was 8.3% (n = 186). More detailed data from 2007 reveals that two-third of the patients were 21–30 years old, 5.12% (n = 114) were male and 3.23% (n = 72) were female, who had intentionally poisoned themselves. In summary, the tertiary care hospitals of the Telangana region, Warangal, indicate that significant opportunities for reducing mortality are achieved by better medical management and further sales restrictions on the most toxic pesticides. This study highlighted the lacunae in the services of tertiary care hospitals and the need to establish a poison information center for the better management and prevention of poisoning cases.

Keywords: Drugs, organophosphorus compound, poisons, mortality and morbidity

INTRODUCTION

Death due to poisoning has been known since time immemorial. Poisoning is a major problem all over the world, although its type and the associated morbidity and mortality vary from country to country. According to the legal system of our country, all poisoning death cases are recorded as unnatural death and a medico-legal autopsy is routine. Toxicology is defined as the study of the effects of chemical agents on biological materials. Modern toxicology is a multidisciplinary science and forensic toxicology is required to determine any exogenous chemical agent present in biological specimens made available in connection with medico-legal investigations.[1]

Organophosphorus poisoning occurs very commonly in southern India, where farmers form a significant proportion of the population who commonly use organophosphorus compounds like parathion as insecticides. Thus, due to the easy accessibility of these compounds, a large number of suicidal cases are encountered in this region.[2] In addition to that, snakebite is a common acute medical emergency faced by rural populations in tropical and subtropical countries with heavy rainfall and humid climate.[3] Some 35,000–50,000 people die each year from snakebite, which is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in India.[4] (Common venomous snakes found in the Mahad region of India are kraits and Echis carinatus.)[5] Kraits are nocturnal in habit. They enter human dwellings during the night in search of prey such as rats, mice and lizards. The peak incidence of snakebite cases is reported during the paddy sowing and harvesting periods, June to November. The common krait, Bunganrs caeruleus, is regarded as the most dangerous species of venomous snake in the Indian subcontinent.[6] The objective of this study is to characterize the poisoning cases admitted to the tertiary care hospital, Warangal district, Andhra Pradesh, Southern India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted at the emergency departments and intensive care units (ICUs) of tertiary care hospital, i.e., Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Hospital, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, which is a 1,000-bedded multidisciplinary super specialty government hospital. The study was carried out for the period of 1 year. The patients included in the study were those who had undergone exposure to poison either by household or agricultural pesticides, stings bite, snake bite, industrial toxins, toxic plants, drug or miscellaneous products. All cases of poisoning, irrespective of age, sex, type and mode of poisoning, ingredients of poisons and the status of patients after poisoning were recorded in the proforma prescribed by WHO guidelines. The emergency department serves residents up to 6 miles west of the middle town area. Data collection was performed according to hospital regulations after approval by the hospital authorities. The setting was the emergency department of an inner city level-one trauma center with approximately 85,000 visits per year. Patients between 1 and 89 years of age and exposed to poisons counting chemical, recreational and/or pharmaceutical agents were selected. The study population consisted of 2,226 poisoning cases admitted between the months of January 2007 and December 2007. The study was conducted in various phases.

PHASE I

Step 1: Identify the type of poisoning inclusion in the study

The general medicine, pediatrics and emergency care department cases from the medical record department were selected for the study as there were many cases of different poisonings being admitted for the treatment of poison with various comorbid conditions.

Step 2: Design of the study

Study period: The study was planned to be carried out for a period of 1 year consent from the hospital authority.

The protocol of the study, which includes the objective and the methodology, were submitted to the Superintendent, MGM Hospital, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, and authorization was obtained to carry out the study.

Step 3: Defining criteria, standards and design of data entry format

Inclusion criteria: Inpatients having OP poisoning, snake bite, drugs, acid, scorpion stings, food poison and any comorbid conditions were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Inpatients having hypertension, cardiac disorders, diabetes mellitus, malaria and terminally ill patients were excluded from the study.

PHASE II

Step 1: Literature survey

The literature supporting the study was collected and analyzed. The different sources used to collect the literature were Micromedex drug information services and various websites such as www.pubmed.com, www.sciencedirect.com and DOAJ.

Step 2: Data collection

Data were collected from patient's case sheets and transferred to data entry format for evaluation. All the data were collected from the Medical record department.

PHASE III

Step 1: Data analysis and interpretation

The collected data were analyzed for their appropriateness and suitability. The interpretation was made for the collected data.

RESULTS

The present study was conducted on 2,226 patients with different poisonings. The patients were admitted to the Emergency Department, MGM Hospital, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh. For diagnosis of poisoning history, intake of poisoning and clinical features like nausea, vomiting, restlessness, excessive thirst, epigastric pain, hypotension, garlic odor in breath and tachypnoea were taken into account. All patients were shifted to the ICU without any delay. For each patient, the following characteristics were recorded: age, gender, deliberate or accidental poisoning, previous suicide attempts and time between poisoning and admission to the ICU. Gastric lavage was performed for all patients approximately 2 h after admission to the emergency room before ICU admission. When monitoring of vital signs showed hypotension or shock, intravenous fluids were administered according to the central venous pressure, which was combined with dopamine or dobutamine infusion to maintain the systolic blood pressure above 80 mmHg. Oxygen was given immediately with the monitoring of clinical respiratory effort of poisons pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas if respiratory distress was present. We used mechanical ventilation in a separate respiratory ICU for suitable cases, alkalinization was used if severe metabolic acidosis was present. We also recorded the length of stay in the ICU, mortality rate and results of the postmortem examination.

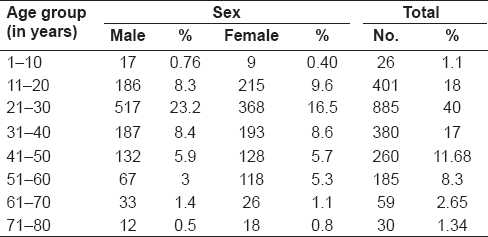

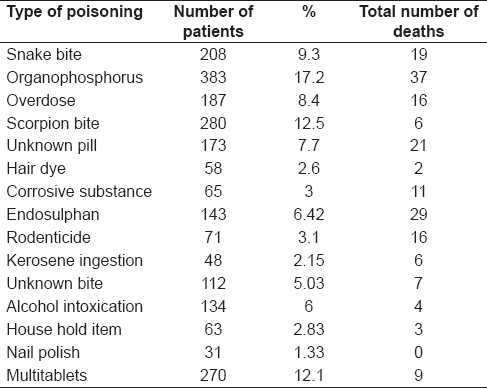

The majority of poison cases were between 21 - 30 years of age. This is represented in Table 1 (included in the text). There were more male patients than females, with 52.15% (n = 1161) and 47.84% (n = 1,065) male and female, respectively. Male poisoning cases were predominantly from rural areas (65%), with reports from urban areas at 35%. The overall case fatality rate was 8.3% (n = 186). Most patients were uninsured (80%), while 20% were covered by the insured, i.e. med claim policy, etc. The pediatric cases were between 1 and 10 years of age, which constituted 1.1% (n = 26) of the total cases. The exposure substances identified as most commonly encountered in the emergency department included snakebite 9.3% (n = 208), OP 17.2% (n = 383), overdose of drugs 8.4% (n = 187), scorpion stings 12.5% (n = 280), unknown pill 7.7% (n = 173), hair dye 2.6% (n = 58), corrosive 3% (n = 65), endosulphan 6.42% (n=143), rodenticide 3.1% (n= 71), kerosene ingestion 2.15% (n = 48), unknown bite 5.03% (n = 112), alcohol intoxication 6% (n = 134), house hold item, i.e. All Out, Baygon Spray 2.83% (n = 63), nail polishes 1.33% (n = 31) and multitablet 12.1% (n = 270). This is represented in Table 2. The exposure circumstances included abuse 32% (n = 720), suicidal 52% (n = 1160), adverse drug reaction (ADR) 9% (n = 208) and others 6% (n = 134). The total mortality rate was 8.3% (n = 186); male 5.1% (n = 114) and female 3.2% (n = 72) exposure.

Table 1.

Number of poisonings by age group and sex

Table 2.

Type of poisoning and its related mortality

DISCUSSION

Poisoning exposure was grouped into 15 toxic substances. Pharmaceutical or medicinal drug use, recreational drug use and chemical exposure were also captured and categorized into intended groups, which included suicide abuse, misuse, unintentional exposure, therapeutic use and adverse drug events (ADE). Males were affected more (52.15%). This finding is similar to that of other studies.[7–9] The high incidence of poisoning in males may be because of the high exposure to stress and strain and also because occupational poisoning occurs due to inappropriate handling (e.g., spraying with high concentration). The signs and symptoms occur due to exposure duration, spraying against wind or lack of personal protection.[10]

Self-poisoning is one of the oldest methods tried for committing/attempting suicide. There are reports available from different parts of the world highlighting various substances abused for acute poisoning and their toxicity. From Western countries, drugs (sedatives and analgesics) have been reported as the most common substances abused, with mortality rates varying between 0.4% and 2.0%.[11–13] Reports available from certain Asian (Pakistan and Sri Lanka) and African countries (Uganda) describe organophosphates (crop sprays) and drugs as the commonly abused toxic substances, with reported mortality rates varying from 2.0% to 2.1%.[14–16] The mortality/morbidity in any case of acute poisoning depends on a number of factors such as nature of poison, dose consumed, level of available medical facilities and the time of interval between intake of poison and arrival at hospital, etc.

The results of our study illustrate that a total of 2,226 patients were hospitalized due to acute poisoning in the hospital. Of these, 186 (8.3%) patients died due to poisoning. The findings of the present study agree with various reports from developing and developed countries, which reveal a considerable increase in mortality and morbidity due to poisoning.[17–28]

The findings of the present study revealed a higher incidence of poisoning in males than in females in all age groups, corroborating other studies.[17–19] There are findings of some other countries where the female has a preponderance.[20,21] The majority of incidences in males was from the age group of 21–30 years .The male preponderance appears to be due to more exposure to occupational hazards and stress or strain as compared with females in this part of the world.

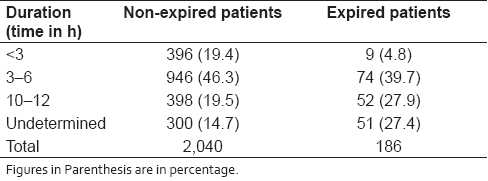

The present study revealed that self-poisoning (suicidal 52%) is the most common manner of acute poisoning, followed by abuse 32%, ADR 9% and others 6%. Results of a 10-year study in Chandigarh revealed that intention was suicide in 72%, followed by accidental (25%).[17] Similar observations were made by other researchers.[18–26] An increase in the number of self-poisonings may be due to many factors such as increases in unemployment, urbanization, break up in family support system and economic instability. Suicide attempts among adults, especially in the age group of 21–30 years, could be due to lack of employment, break up in the family support system, failure of love affairs, an individual's frustrations, inadequacy to cope with some immediate situation, impulsive behaviors, stress due to job and family, etc. Results of some studies reported that many deaths are due to organophosphate pesticides and occur in the young, economically active age group.[18,27–29] Recent studies have shown that a high mortality is due to depression leading to suicide.[30–32] It has been established that consistent exposure, especially to organophosphate pesticides, produces a distinct pattern of physical symptoms and has psychological and neurobehavioral effects such as anxiety, depression and cognitive impairment.[33,34] These findings are corroborated with others findings. The morbidity and mortality due to acute poisoning have been mainly due to agrochemicals, which appear to be a by-product of the “green revolution” in South Asia. There are few published studies of agrochemical poisoning in developed countries. A review of pesticide poisoning deaths in England and Wales found that pesticides were responsible for only 1.1% of poisoning deaths over a 44-year period.[35–36] A Minnesota regional poison center consulted on 1,428 cases in 1988, in which a pesticide was the primary substance, accounting for approximately 4.5% of all poisoning cases.[37] The present study revealed that the maximum cases of self-poisoning were due to organophosphate pesticides in South India, which is different from the results of North Indian studies. In North India, the majority of poisoning was due to aluminum phosphide.[17–19,27] Results of a prospective study (559 cases) conducted at a medical college hospital in Rohtak, Haryana, North India, revealed that aluminum phosphide was the primary substance accounting for approximately 67.8% of all poisoning cases.[22] This could be because of the easily availability of organophosphate pesticide in this region of the country. Poisoning due to organophosphate was also the most common poisoning in North India before the 1980s.[17,18,27] Now-a-days, aluminum phosphide is most commonly used for storing wheat grain in North India, and it is easily available in the market and in small shops. A study of 117 cases of poisoning reported from Tamilnadu during 1992–1993 showed that most common poisonings (63%) were due to a plant called “Oduvan,” and agrochemicals accounted for only 2.2% of the cases.[23] Results of the present study show that a higher mortality rate resulted due to organophosphate pesticides. This shift of poisoning from plant origin to pesticides is similar to the reports by the other researchers. This may be because of easy availability, and uncontrolled sales and use of these agents. In North India, the switching to other highly toxic agents (aluminum phosphide) from organophosphate[38] was observed. Among the total deaths reported, the majority (60%) was of patients arriving at the hospital after 6 h. Those patients (80% of total poisoning cases) who reached the hospital early, i.e. within 6 h, managed properly and were discharged from the hospital [Table 3].

Table 3.

Intervals between intake of poison and arrival at hospital

CONCLUSION

The tertiary care hospitals of the Telangana region, Warangal, indicate that significant opportunities for reducing mortality exist by better medical management and further restrictions on the most toxic pesticides. This study highlighted the lacunae in the services of tertiary care hospitals and the need to establish a poison information center for the better management and prevention of poisoning cases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members of the MRD section of MGM Hospital, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, India, for their help and support. The authors would also like to thank the Superintendant, Dr. E. Ashok Kumar, Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Hospital, Warangal, for his valuable suggestions and support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muhammad NI, Nasimul I. Retrospective study of 273 deaths due to poisoning at Sir Salimullah Medical College from 1988 to 1997. Leg Med. 2003;5:S129–31. doi: 10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanchan T, Menezes RG. Suicidal poisoning in Southern India: Gender differences. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banejee RN. Poisonous snakes and their venoms, symptomatology and treatment. In: Ahuja MM, editor. Progressin Clinical Medicine, Second Series. India: Heinemann; 2003. pp. 136–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warrell DA. International Panel of Experts. The clinical management of snake bites in the South Asian region. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;1:1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH. Snake bite. Bombay Hosp J. 1992;34:190–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theakston RD, Phillips RE, Warrell DA, Galagedera Y, Abeysekera DT, Dissanayaka P, et al. Envenoming by the common krait (Bungams caeruleus) and Sri Lankan cobra (Naja naja nuja): Efficacy and complications of therapy with Haffkine antivenom. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:301–8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90297-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairans FJ, Koelmeyer TD, Smeeton WM. Deaths from drugs and poisons. N Z Med J. 1982;96:1045–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimal S, Laxman K. Pattern of acute poisoning in a medical unit in central Srilanka. Forensic Sci Int. 1988;36:101–4. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(88)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tendon SK, Qureshi GU, Pandey DN, Aggarwal A. A profile of poisoning cases admitted in S.N. Medical College and Hospital, Agra. J Forensic Med Toxicol. 1996;13:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagandeepa S, Dheeraj K. Neurology of acute organophosphate poisoning. Neurol India. 2009;57:119–25. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.51277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans GJ. Deliberate self-poisoning in Oxford area. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1967;21:97–107. doi: 10.1136/jech.21.3.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AJ. Self- poisoning with drugs: A worsening situation. Br Med J. 1972;4:57–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5833.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rygnestad T. A comparative prospective study of self-poisoned patients in Trondheim, Norway between 1978 and 1987: Epidemiology and clinical data. Hum Toxicol. 1989;8:75–82. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardozo LJ, Mugerwa RD. The pattern of acute poisoning in Uganda. East Afr Med J. 1972;42:983–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senewiratne B, Thambipillai S. Pattern of poisoning in a developing agricultural country. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28:32–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.28.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamil H. Acute poisoning: A review of 1900 cases. J Pak Med Assoc. 1990;40:131–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh S, Sharma BK, Wahi PL. Spectrum of acute poisoning in adults (10 years experience) J Assoc Physicians India. 1984;32:561–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Wig N, Chaudhary D, Sood N, Sharma B. Changing pattern of acute poisoning in adults: Experience of a large North West Indian hospital (1970–1989) J Assoc Physicians India. 1997;45(3):194–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma BR, Harish D, Sharma V, Vij K. Poisoning in Northern India: Changing trends, causes and prevention There of. Med Sci Law. 2002;42:251–7. doi: 10.1177/002580240204200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tufekci IB, Curgunlu A, Sirin F. Characteristics of acute adult poisoning cases admitted to a university hospital in Istanbul. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2004;23:347–51. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht460oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita M, Matsuo H, Tanaka J. Analysis of 1000 consecutive cases of acute poisoning in the suburb of Tokyo leading to hospitalization. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1996;38:34–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siwach SB, Gupta A. The profile of acute poisoning in Haryana. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;13:756–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aleem MA, Paramasivam M. Spectrum of acute poisoning in villagers. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:859. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hettiarachchi J, Kodithuwakku CS. Pattern of poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:418–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hettiarachchi J, Kodithuwakku CS. Self poisoning in Sri Lanka: Factors determining the choice of poisonous agent. Hum Toxicol. 1989;8:507–10. doi: 10.1177/096032718900800613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernado R. National poisons information centre in developing Asian country: The first year's experience. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1990;9:161–3. doi: 10.1177/096032719000900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lall SB, Peshin SS, Seth SS. Acute poisoning: A ten years retrospective hospital based study. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci. 1994;30:35–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh S, Singh D, Wig N, Jit I, Sharma BK. Aluminium phosphide ingestion a clinico pathologic study. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:703–6. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eddleston M, Sheriff MH, Hawton K. Deliberate self-harm in Sri Lanka: An overlooked tragedy in the developing world. Br Med J. 1998;317:133–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van der Hoek W, Konradsen T, Athulorala K, Wanigadowa T. Pesticide poisoning a major health problem in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:495–504. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddleston M, Singh S, Buckley N. Acute organophosphorus poisoning. Clin Evid. 2003;9:1542–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depression and suicide: Are they preventable? Lancet. 1992;340:700–1. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parron T, Antonio FH, Enrique V. Increased risk of suicide with exposure to pesticides in an intensive agricultural area: A 12-years retrospective study. Forensic Sci Int. 1996;79:53–63. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(96)01895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell IR, Miller CS, Schwartz GE. An olfactory-limbic model of multiple chemical sensitivity syndromes: Possible relationship to kindling and affective spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:218–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Repetto MR. Epidemiology of poisoning due to pharmaceutical products: Poison control Centre, Siville, Spain. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:353–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1007384304016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casey P, Vale JA. Deaths from pesticide poisoning in England and Wales: 1945-1989. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1994;13:95–101. doi: 10.1177/096032719401300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson DK, Sax L, Gunderson P, Sioris L. Pesticide poisoning surveillance through regional poison control centers. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:750–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.6.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhoopendra S, Unnikrishnan B. A profile of acute poisoning at Mangalore (South India) J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]