Abstract

Organisms react to threats with a variety of behavioral, hormonal, and neurobiological responses. The study of biological responses to stress has historically focused on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, but other systems such as the mesolimbic dopamine system are involved. Behavioral neuroendocrinologists have long recognized the importance of the mesolimbic dopamine system in mediating the effects of hormones on species specific behavior, especially aspects of reproductive behavior. There has been less focus on the role of this system in the context of stress, perhaps due to extensive data outlining its importance in reward or approach-based contexts. However, there is steadily growing evidence that the mesolimbic dopamine neurons have critical effects on behavioral responses to stress. Most of these data have been collected from experiments using a small number of animal model species under a limited set of contexts. This approach has led to important discoveries, but evidence is accumulating that mesolimbic dopamine responses are context dependent. Thus, focusing on a limited number of species under a narrow set of controlled conditions constrains our understanding of how the mesolimbic dopamine system regulates behavior in response to stress. Both affiliative and antagonistic social interactions have important effects on mesolimbic dopamine function, and there is preliminary evidence for sex differences as well. This review will highlight the benefits of expanding this approach, and focus on how social contexts and sex differences can impact mesolimbic dopamine stress responses.

Introduction

Stressful experiences induce a powerful set of behavioral, hormonal, cellular and molecular responses that assist organisms in adapting to the physical and social environment. Studies of physiological stress responses have historically focused on catecholamine responses and the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis (Herman et al. 2003; McEwen and Wingfield 2003). However physiological responses to stress are diverse, and over the past 30 years evidence has accumulated that dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), (which project to limbic regions including the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, hippocampus, and frontal cortex) react strongly to stressful situations (Thierry et al. 1976; Herman et al. 1982; Tidey and Miczek 1996). Reports that the mesolimbic dopamine system reacts to stress were initially slow to attract wide interest, perhaps because they run counter to prevailing views that the pathway is primarily activated by contexts associated with rewards. Despite these headwinds, interest in mesolimbic dopamine responses to stress and aversive contexts is growing. Recent discoveries suggest that there may be distinct populations of VTA neurons that are preferentially activated by rewards or stress. Furthermore individual variation in VTA stress responses has been linked to individual differences in coping responses to stress (Krishnan and Nestler 2010). These discoveries are contributing to our still evolving understanding of the functions of mesolimbic dopamine neurons in behavior (Ikemoto and Panksepp 1999; Wise 2004; Hyman et al. 2006; Berridge 2007; Bromberg-Martin et al. 2010).

How an individual responds behaviorally and physiologically to challenges is influenced by an array of factors including early life experience (Seckl and Meaney 2004), seasonal cues (Nelson and Martin 2007), social environment (DeVries et al. 2007), and sex (Goel and Bale 2009). These factors are known to modulate how the HPA axis responds to stress. However, less is known about how these factors mediate mesolimbic dopamine responses to stress. Indeed, the majority of studies investigating dopaminergic responses to stress have focused on a few species of male rodents under relatively controlled laboratory conditions. Here, I will argue that there will be many benefits to diversifying the contexts in which the activity of the mesolimbic dopamine system is studied. The literature focusing on appetitive aspects of mesolimbic dopamine function has already started this process. A foundation of knowledge was formed by focusing on dopaminergic function in a few model species, under a limited set of controlled conditions (e.g. responses to food rewards or drugs of abuse) (Hyman et al. 2006; Wise 2006). This set the stage for interpreting how the mesolimbic dopamine system functions in more complex social situations. For example, the formation of a pair bond between a male and a female prairie vole induces a dramatic upregulation of dopamine D1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), which causes males to attack unfamiliar females (Aragona et al. 2006). These results contrast starkly from observations in rats. Unfamiliar females rats typically induce increased male sexual arousal (Wilson et al. 1963) and increase dopamine release in the NAc (Fiorino et al. 1997). Several lines of evidence suggest that dopamine receptors (including D1 receptors specifically) in the NAc facilitate male sexual motivation in rats (Everitt et al. 1989; Pfaus and Phillips 1991; Liu et al. 1998; Bialy et al. 2010) but see (Moses et al. 1995). Thus, species differences in social organization are associated with divergent effects of dopamine receptors on male behavioral responses to novel females. This example highlights the value of comparative approaches.

This review will examine mesolimbic dopamine responses to aversive contexts (focusing on the VTA and NAc), and then focus on how social context and sex differences modulate these responses. Although most examples will come from a few widely used rodent model systems, this review will highlight the unique insights that can be gained from examining mesolimbic dopamine function under different social contexts, and in species with different social systems.

Mesolimbic dopamine system

Appetitive responses

The mesolimbic dopamine pathway consists of dopaminergic cell bodies in the VTA and its projections to striatal, limbic, and cortical regions. The NAc can be divided into two subregions: the core which has stronger connections to other nuclei within the basal ganglia (Zahm and Heimer 1990) and the shell which has stronger connections to the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Alheid and Heimer 1988). Both natural rewards such as palatable foods (Baldo and Kelley 2007) and artificial stimuli such as drugs of abuse (Di Chiara et al. 2004) stimulate dopamine release in the NAc. However, it appears the consequences of dopamine release in the NAc are more complex than indicating the presence of a reward. For example, several findings suggest that NAc dopamine release does not signal a hedonic (pleasurable) state. Inhibiting dopaminergic responses in the NAc, either via pharmacological lesion (Berridge et al. 1989) or through genetic inactivation of dopamine synthesis (Cannon and Palmiter 2003), does not block behavioral preferences for rewards. Genetic deletion of dopamine synthesis in the NAc inhibits animals from seeking or working for rewards (Robinson et al. 2005), suggesting that dopamine released in the NAc may be more important for reinforcement (Berridge 2007; Salamone et al. 2007). Electrical recordings of dopamine neurons in the VTA during learning tasks suggest these neurons also play a role in learning. The activity of dopamine neurons increases following unexpected rewards, and over time “burst” responses are stimulated by cues that predict the onset of the reward rather than the reward itself (Schultz et al. 1997). With these discoveries in male rats, mice, and rhesus monkeys, hypotheses on the role of dopamine function in the context of natural and artificial rewards have shifted. Focusing on a few species has facilitated these major advances, but as outlined below, considering species with different social systems can facilitate important insights. This is because the behavioral responses of dopamine neurons are context dependent, and examining species with different social systems expands the range of contexts that can be studied.

There is substantial evidence from a wide range of vertebrates that sexual behavior is perceived as a rewarding experience (Pfaus and Phillips 1991; Domjan 1992; Burns-Cusato et al. 2005; Tenk et al. 2009). However, there are some interesting species differences in how dopamine is released during mating. Rats live in complex social groups, and sexual behavior typically involving intense competition among males for mating opportunities (Calhoun 1962). Under naturalistic conditions or cages in which females can avoid males, females control the pacing of sexual interactions by approaching and withdrawing from males (McClintock and Anisko 1982; Erskine 1989). This behavior has also been observed in Mus musculus (Garey et al. 2002). Intriguingly, dopamine release in the NAc of female rats increases during paced mating but does not increase when males have unrestricted access to females (Mermelstein and Becker 1995; Becker et al. 2001; Jenkins and Becker 2003). In contrast, female golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) are solitary (Gattermann et al. 2001; Gattermann et al. 2008) and have increased NAc dopamine release during mating tests in which male hamsters have unrestricted access to females (Meisel et al. 1993; Kohlert et al. 1997). On the one had, female hamster sexual behavior would appear to be a less dynamic process, as females often adopt the lordosis posture for several minutes at a time (Lisk et al. 1983). However, a closer examination showed that female hamsters can indeed pace mating bouts through perineal movements (Noble 1980). This apparent pacing behavior in hamsters appears to increase the number of successful matings (Noble 1980). Currently, it is unclear whether this more subtle pacing behavior in hamsters is critical for facilitating dopamine release, although there is some indirect evidence for a connection. Cytotoxic lesions of dopamine neurons of the basal forebrain (including nucleus accumbens) prevents increases in mating efficiency that occur with sexual experience in females (Bradley et al. 2005). It would be interesting to determine how female dopamine responses in the NAc vary across species with different levels of mating competition. One possibility is that in species with fewer mating partners, dopamine release might not be as tightly linked to mating behavior compared to other courtship cues. In monogamous zebra finches, male courtship behavior is positively correlated with the number of c-fos positive tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) neurons in the caudal VTA (Goodson et al. 2009), and electrophysiological recording suggest that VTA neurons are more active during male courtship behavior (Huang and Hessler 2008). It’s not yet clear how these neurons respond to courtship behavior in females, and dopamine release following sexual behavior has not yet been examined. An intriguing, yet relatively unexplored question is whether VTA dopamine neurons play a role in the selection of mating partners. Increasing dopaminergic activity systemically appears to decrease the selectivity of mate searching behavior in female starlings (Pawlisch and Riters 2010). These data resemble findings that methamphetamine increases the probability that female rats will mate with less preferred males (Winland et al. 2011) and reports that methamphetamine use in humans is associated with increased numbers of sexual partners (Molitor et al. 1998).

Aversive responses

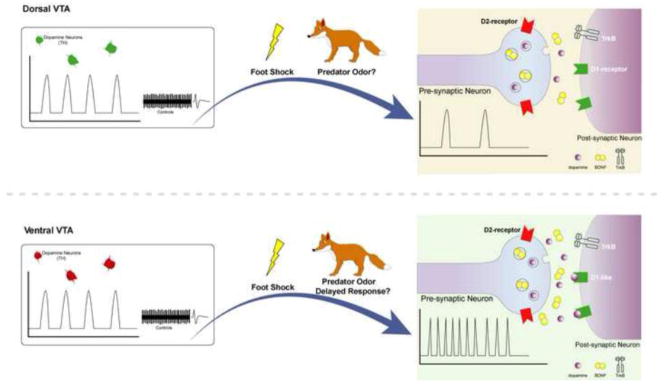

As hypotheses related to the function of mesolimbic dopamine neurons in appetitive situations have evolved, there has been a growing appreciation that VTA dopamine neurons are important in aversive situations. Several studies using electrophysiological recordings demonstrated that aversive stimuli can alter the activity of VTA neurons, either increasing or decreasing activity (Maeda and Mogenson 1982; Mantz et al. 1989; Guarraci and Kapp 1999; Wang and Tsien 2011). In these studies dopamine neurons were identified by electrophysiological properties, an approach that became controversial after the discovery that some nondopaminergic VTA neurons have similar electrophysiological profiles as dopaminergic neurons (Margolis et al. 2006). It has been suggested that immunostaining TH may be a more accurate approach for identifying dopamine neurons in the VTA (Margolis et al. 2010). Using this approach Ungless and colleagues determined that the majority of VTA neurons in rats that respond to a toe pinch were TH negative and therefore unlikely to be dopamine neurons (Ungless et al. 2004). However, further investigation revealed a more complex relationship between VTA dopamine neurons and aversive stimuli. In rats, it appears that there are different populations of dopamine neurons that may differentially respond to reward related stimuli or aversive stimuli (Fig. 1). Dopamine neurons in the dorsal VTA were observed to be inhibited by footshocks whereas dopamine neurons in the ventral VTA were excited by footshocks (Brischoux et al. 2009). The results provide a potential explanation for why dopamine release in the NAc can be observed both after rewards and aversive experiences. It is important to note that recordings were conducted on anesthetized animals, and the shocks used were much more intense than typically used in aversive conditioning paradigms (Gross et al. 2000; Darvas et al. 2011; Spannuth et al. 2011). It will be important to examine whether similar results are observed in awake behaving animals, and whether different types of stressors induce different profiles of neuronal responses in the VTA.

Figure 1.

Responses of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons to aversive stimuli. Electrophysiological studies show that there is variability in the responses of VTA dopamine neurons. Work by Brischoux et al. showed that more ventral VTA neurons responded to footshocks with increased activity whereas more dorsal VTA neurons were inhibited by footshock. These changes in activity would be expected to correspond to changes in dopamine (and possibly BDNF) release in axon terminals, although this has not yet been measured directly. The effects of predator odors (which induce delayed dopamine release) on VTA neurons has not been examined.

In addition to changing the activity of VTA neurons, stressful experiences such as restraint (Abercrombie et al. 1989; Copeland et al. 2005; Ling et al. 2009) and footshock (Thierry et al. 1976; Herman et al. 1982; Kalivas and Duffy 1995), induce dopamine release or dopamine turnover in the NAc shell. Interestingly, this rapid dopamine response quickly habituates when restraint is applied on consecutive days (Imperato et al. 1992). The mechanism mediating this plasticity has not yet been identified. In contrast, a surge of dopamine release occurs immediately after rats are removed from restraint tubes, and this response does not diminish over repeated episodes of restraint (Imperato et al. 1992). This dopamine response may serve to reinforce behaviors that were associated with escape, although this hypothesis has not been tested directly. Studies investigating the role of the NAc in the formation of fear memories have reported mixed results (Josselyn et al. 2004). One trend that has emerged is that the NAc appears to be less important for learning that specific cues (a sound or light) predict aversive events like footshock (Riedel et al. 1997; Jongen-Relo et al. 2003; Bradfield and McNally 2010). In contrast, the NAc appears to be more important for learning contextual cues (smells, or the general area in which training occurred) that predict aversive events (Levita et al. 2002). For the most part the literature investigating the electrophysiological responses of VTA neurons to aversive stimuli has not been directly paired with measurements of dopamine release in the NAc (Ungless et al. 2010).

To date the majority of studies examining mesolimbic dopamine responses to aversive experiences have used artificial stimuli such foot shock. A few studies have examined dopaminergic responses to more natural stressors such as predator odor in male rats. Rats exposed to fox odor for 20 min increased dopamine turnover in the amygdala and frontal cortex but not NAc (Morrow et al. 2000). These data agreed with a subsequent study which showed that NAc dopamine responses to predator odors are delayed. A microdialysis study showed that 5 min of fox odor exposure did not increase NAc shell dopamine release until 40 min later (Fig. 1, Bassareo et al. 2002). Dopamine remained elevated for about 20 min and then returned to baseline levels. This study also showed that predator odors induced a rapid increase in frontal cortex dopamine release. Interestingly, although dopamine release in the NAc is not induced rapidly by fox odor, changes in other neurotransmitters do occur. Fox odor rapidly induces an increase in both GABA and glutamate release, but these responses are only observed in individuals with strong behavioral responses to fox odor (Hotsenpiller and Wolf 2003; Venton et al. 2006).

In general, less is known about mesolimbic dopamine responses under aversive contexts compared to appetitive contexts. Our knowledge base is growing, but most data come from studies under controlled conditions and are usually based on artificial stimuli such as restraint or footshock. There are hints that there are important insights to be gained by examining natural stressors. Restraint and footshock induce a rapid increase in NAc dopamine release whereas the response to predator odors is delayed. As discussed below, there is considerable evidence that social factors have important effects on how the mesolimbic dopamine system responds to aversive contexts.

Effects of Social Context

Social factors are known to have important effects on behavioral responses to stress, sometimes exerting a buffering effect. Studies examining the effects of social isolation highlight the importance of positive social interactions on brain and behavior. However, social interactions can also be a powerful source of stress, especially aggressive interactions. Indeed, many species engage in elaborate signals and threats to settle disputes without fighting (Altmann 1962; Reby et al. 2005). When an aggressive contest does occur, the loser usually adopts one of several behavioral coping responses (Veenema et al. 2005; Koolhaas et al. 2007). One widely observed behavioral responses to losing aggressive contests is withdrawal from social contact. This effect has been observed in several species of rodents (Kudryavtseva et al. 1991; Meerlo et al. 1996; Trainor et al. 2011) and birds (Carere et al. 2001). Social withdrawal following aggressive contests has also been observed in primates (Bernstein and Sharpe 1966), although reconciliation between winners and losers is also common (Silk et al. 1996). An additional intriguing observation is that there is a striking degree of individual variation in behavioral responses to social stressors (Wommack and Delville 2003; Schmidt et al. 2009). This variability is also observed within mouse strains such as C57Bl6 (Krishnan et al. 2007; Elliott et al. 2010), which are often assumed to be relatively homogenous as the mice are inbred and housed in relatively constant conditions. There is also growing interest in how the social environment during development impacts the brain and behavior (Marler et al. 2003; Roth et al. 2009; Bales et al. 2011). As reviewed below, social interactions during development and in the mature adult can have long lasting effects on the function of the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Social Instability During Development

Adolescence is a critical time period in which a great deal of neurobiological development occurs (Sisk and Foster 2004), including within the mesolimbic dopamine system (Leslie et al. 1991; Coulter et al. 1996; Tarazi et al. 1998). Developmental studies in rats show that males greatly increase D1-like and D2-like receptors in the NAc at the time of puberty whereas changes in dopamine receptor expression are less pronounced in females (Andersen et al. 1997; Andersen et al. 2002). Most studies examining the effects of stress during development on mesolimbic dopamine function have focused on responses to drugs of abuse. In humans exposure to stress during adolescence increases risk of drug abuse (King and Chassin 2008), a process that is linked to changes in mesolimbic dopamine function (Dietz et al. 2009). It has been hypothesized that social stress during adolescence alters the “programming” of the mesolimibic dopamine system, potentially making it more sensitive to drugs of abuse (McCormick 2010). However, there is also evidence that stress during adolescence can lead to desensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine system (Gatzke-Kopp 2011). Further study is needed to titrate how different forms and durations of stress during development can lead to alternate behavioral phenotypes.

Social instability is one form of stress that can impact behaviors regulated by the mesolimbic dopamine system. One approach to inducing social instability in rodents is to routinely switch cage partners. Two studies in rats reported that this form of social instability, when conducted during adolescence, increases sensitivity to amphetamine (McCormick et al. 2005; Mathews et al. 2008). Amphetamine induces the release of dopamine in the striatum and also blocks dopamine reuptake. This increased dopaminergic activity increases locomotor behavior in rodents and this effect becomes exaggerated with repeated exposure to amphetamine (sensitization). Social instability during adolescence facilitated the sensitization of locomotor responses to amphetamine and this effect was larger in females than males. Social instability also strengthened the formation of conditioned place preferences (which is an indirect measure of reward value) for higher doses of amphetamine in females but not males. Interestingly, social instability during adulthood had no effect on behavioral responses to amphetamine. However, social instability in adulthood is known to affect other aspects of behavior and brain function (Schmidt 2010). When social instability was combined with other forms of stress such as crowding and novel environments, behavioral responses to amphetamine where actually reduced (Kabbaj et al. 2002). The authors hypothesized that the complex set of experiences used may have resembled environmental enrichment, because juvenile rats housed under enriched environmental conditions also are less behaviorally reactive to repeated amphetamine (Bardo et al. 1995).

Effects of Social Isolation

Social interactions are an important factor modulating behavioral and neurobiological responses to stress. Social interactions in rodents have been found to be reinforcing (Stewart and Grupp 1985; Van den Berg et al. 1999), so it is not surprising that social isolation exerts powerful effects on the brain and behavior. A complicating factor in rodent studies of isolation is that there are important sex differences. Results from studies of female rodents are more intuitive, with most evidence pointing towards social isolation exerting an anxiogenic effect (Westenbroek et al. 2003; Grippo et al. 2008) In contrast socially housed male rodents often engage in aggressive interactions in the their home cage (Van Loo et al. 2000; Howerton et al. 2008), which may explain why most data suggest that social isolation has anxiolytic effects in males (Westenbroek et al. 2003; Thorsell et al. 2006; Workman et al. 2008, but see Ruis et al. 1999; Von Frijtag et al. 2000). Most of what is known about the effects of social isolation on brain function comes from studies on male rodents. The dramatic sex differences in the effects of isolation on behavior illustrate the need for a greater emphasis on sex differences in neuroscience research (Beery and Zucker 2011).

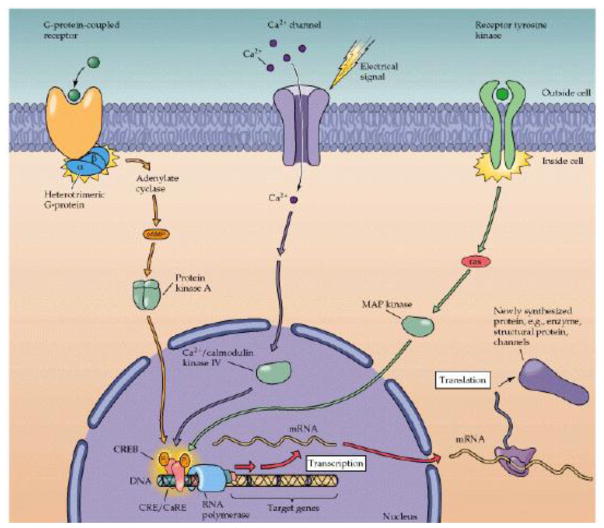

In general most studies report that long term social isolation increases male presynaptic dopamine function in the NAc. Socially isolated male rats have higher levels of tyrosine hydroxylase in the NAc shell and have exaggerated dopamine responses to drugs of abuse (Jones et al. 1990; Robbins et al. 1996; Hall et al. 1998). The effects of isolation on dopamine responses in the NAc to stressors may depend on context. Dopamine turnover following footshock was exaggerated in isolated males (Ahmed et al. 1995; Fulford and Marsden 1998) but dopamine turnover was reduced following exploration of a novel environment (Miura et al. 2002). A series of studies suggest reduced dopamine turnover in the NAc shell could influence behavior via reduced activation of D1 receptors. Activation of D1 receptors induces activation (phosphorylation) of the transcription factor cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), which is known to modulate exploratory behavior in novel environments (Fig. 2). In male C57Bl6 mice, social isolation decreases the expression of CREB in the NAc shell (Barrot et al. 2005), which is consistent with a decrease in D1 receptor signaling. Furthermore, adult male C57Bl6 mice and Sprague-Dawley rats that are socially isolated show decreased exploratory behavior in a novel environment (Pinna et al. 2006), a behavior that is regulated by the NAc shell. Overexpression of CREB in the NAc shell increased exploratory behavior, reversing the effects of social isolation (Barrot et al. 2005; Wallace et al. 2009). Activation of CREB also occurs in response to other stressful contexts such as footshock, restraint, and social defeat (Barrot et al. 2002; Muschamp et al. 2011). Although overexpression of CREB in the NAc does not alter the development of conditioned fear to footshock, it does impair the extinction of contextual fear-based memories (Muschamp et al. 2011). This finding is consistent with data from male C57Bl6 mice, in which isolation inhibits the extinction but not formation of fear memories (Pibiri et al. 2008). Intriguingly, housing under semi-natural, enriched conditions appears to mediate at least some of the developmental effects of social isolation on the NAc (Lesting et al. 2005).

Figure 2.

Molecular pathways leading to the activation of CREB (From Purves et al; Neuroscience, 2nd edition, used with permission). Activation of certain G-protein coupled receptors (such as D1 dopamine receptors) increases the production of cyclic AMP, leading to the phosphorylation of CREB. However, other G-protein receptors (such as D2 dopamine receptors) can have the opposite effect on cyclic AMP production with would inhibit phosphorylation of CREB. Activation of tyrosine kinase receptors (such as when BDNF binds to TrkB) increases phosphorylation of MAP kinase (also known as ERK) which then facilitates phosphorylation of CREB. Neuronal activity can also increase phosphorylation via opening of voltage gated calcium channels.

In summary, the effects of social isolation on mesolimbic dopamine function are context dependent. When exploring novel environments, social isolation reduces dopamine turnover, and this would presumably reduce the activation of CREB by D1 receptors (Fig. 2). Decreased CREB activation would be expected to reduce exploratory behavior, which matches empirical observations in male rats and mice. In contrast, social isolation enhances mesolimbic dopamine responses to footshock, and mesolimbic dopamine signaling has been found to modulate the extinction of fear memories (Pezze and Feldon 2004). These observations may help explain why the extinction of fear memories is inhibited by social isolation. As mentioned previously, the effects of social isolation on neurobiological mechanisms of behavior have been understudied in females. Addressing this deficit should be a priority for future studies.

Social Defeat

As mentioned previously, aggressive interactions can be a powerful source of stress, especially for individuals that lose aggressive contests. Aggressive interactions in general increase either dopamine release or indirect markers of dopamine activity in a wide range of vertebrates (Winberg et al. 1991; Filipenko et al. 2001; Bharati and Goodson 2006; Bondar et al. 2009). Studies of social defeat focus on animals that have been randomly assigned to be exposed to aggressive interactions. Postmortem analyses of dopamine turnover (Louilot et al. 1986; Puglisi-Allegra and Cabib 1990) as well as microdialysis studies (Tidey and Miczek 1996) show that exposure to social defeat in particular increases dopamine release in the NAc but not dorsal striatum. Social isolation exaggerates both behavioral (Ruis et al. 1999) and neurobiological (Isovich et al. 2001) responses to defeat in rats. In addition to these short term responses, social defeat induces long lasting changes in the activity of both the VTA and NAc (Miczek et al. 2008; Krishnan and Nestler 2010). Many of these changes are known to contribute to the effect of defeat on social withdrawal.

In rats, social defeat induces long lasting increases in brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression and protein within the VTA (Fanous et al. 2010). The effects of growth factors such as BDNF on brain function are not limited to development. Neurotrophins such as BDNF are known to have many important effects on the adult brain (McAllister et al. 1999) and are sensitive to stress (Duman and Monteggia 2006). The receptor for BDNF is the TrkB receptor, and its activation leads to phosphorylation of extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) and thymoma viral proto-oncogene (AKT), which are important signaling kinases (Fig. 2). In C57Bl/6 mice ten days of social defeat increases expression of phosphorylated (activated) ERK in the VTA (Iñiguez et al. 2010). Social defeat also decreases the activation (phosphorylation) of AKT, also known as protein kinase B, within the VTA (Krishnan et al. 2008). Overexpression of a constitutively active AKT in the VTA blocks the effect of defeat on social withdrawal. In contrast overexpression of an inactive form of AKT (a dominant negative protein) induces social withdrawal after only three brief episodes of social defeat on a single day. Increased ERK signaling and decreased AKT signaling in the VTA appear to exert their effects on behavior by altering the activity of dopamine neurons. Overexpression of ERK in the VTA increases the excitability of VTA dopamine neurons in slice culture (Iñiguez et al. 2010) whereas drugs that inhibit AKT activity have a similar effect (Krishnan et al. 2008). Social defeat may also increase activity of VTA neurons by increasing sensitivity to glutamate (Covington et al. 2008).

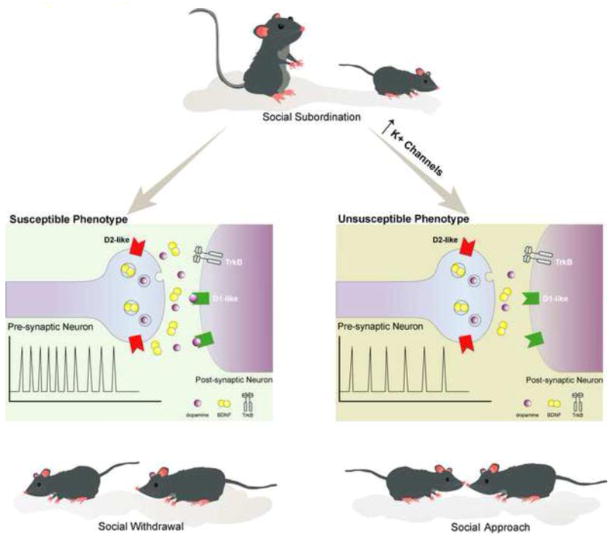

Social defeat increases the firing rate of VTA neurons in in vitro slice preparations (Krishnan et al. 2007). Chronic antidepressant treatment, which blocks social withdrawal responses (Berton et al. 2006; Tsankova et al. 2006), also blocked the effects of social defeat on elevated VTA neuronal activity (Krishnan et al. 2007). These studies measured tonic firing (or single spike) activity, which is more closely associated with steady state dopamine release. However VTA neurons are also capable of burst firing, which associated with larger increases in dopamine release that can last several seconds (Grace 1991). Restraint stress has been observed to increase burst firing in about 80% of VTA neurons (Anstrom and Woodward 2005). As measured via in vivo recordings, increased burst firing in VTA neurons was observed during social defeat in rats (Anstrom et al. 2009). This observation is consistent with observations of increased dopamine release (as measured via microdialysis) in the NAc during social defeat (Tidey and Miczek 1996). Social defeat was also observed to decrease burst firing three weeks after social defeat in mice (Razzoli et al. 2011). These recordings in mice were made under isoflurane anesthesia, indicating that the increased activity in the VTA was a long term change in activity as opposed to a transient response to social threat. Intriguingly, a subpopulation of C57Bl6 mice that are exposed to defeat develop an “unsusceptible” phenotype, characterized by the absence of social withdrawal that is observed in “susceptible” mice (Fig. 3, (Krishnan et al. 2007). When in vivo observations were conducted on susceptible and unsusceptible mice, burst firing of VTA neurons was increased in susceptible mice and negatively correlated with social interaction behavior (Cao et al. 2010). It should be noted that all studies examining the effects of social defeat on VTA neuronal activity used electrophysiological criteria to classify dopamine neurons. While it is highly likely that dopamine neurons were actually examined in these studies, future studies should use tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry to confirm dopaminergic status.

Figure 3.

Susceptible and unsusceptible phenotypes are associated with different activity profiles in the VTA. In male mice, two phenotypes are induced by social defeat. The susceptible phenotype is associated with increased burst activity by VTA neurons and increased BDNF release in the NAc. Increased dopamine release in the NAc has been observed during social defeat, but has not yet been measured during social interaction tests following social defeat. Unsuceptible mice increase the expression of K+ channels, which prevents increased burst activity and subsequent changes in BDNF release.

Surprisingly, despite numerous observations that social defeat alters the activity of VTA neurons, how this activity translates into altered patterns of dopamine release or dopamine receptor activation within the NAc has not been extensively examined. However, changes in other cellular pathways in the NAc have been reported. Social defeat in C57Bl6 mice increases expression of BDNF protein in the NAc (Berton et al. 2006). Since BDNF mRNA is undetectable in NAc, it is assumed that the source for this BDNF is the VTA. Supporting this observation, selective deletion of BDNF in the VTA blocks the effects of defeat on social withdrawal (Berton et al. 2006). Increased BDNF signaling at the TrkB receptor should increase activation of ERK, and indeed social defeat increases phosphorylation (or activation) of ERK in the NAc (Krishnan et al. 2007). When ERK function is inhibited via overexpression of a dominant negative ERK protein in NAc, the effects of defeat on social avoidance behavior were blocked. Interestingly, overexpression of a constitutively active form of ERK2 in the NAc of mice exposed to only 3 episodes of social defeat on a single day induced social avoidance, but had no effect in control mice. This is important because it demonstrates that increased activation of the VTA-NAc circuit alone is not sufficient to induce the social avoidance phenotype, it must occur in the context of an adverse experience.

Social Subordination

The effects of aggressive interactions on the mesolimbic dopamine system have also been observed under more natural conditions. In contrast to social defeat, in which animals are randomly assigned, studies of social subordination focus on subordinate individuals within a social group. The visible burrow system (VBS) was designed to observe the effects of social status in a more naturalistic setting with more complex social groups (usually with males and females) than typically used in laboratory experiments (Blanchard and Blanchard 1989). The apparatus is about 1 m2 and consists of numerous chambers connected with tubes, roughly mimicking burrow systems created by wild rats. After introduction into the VBS, subordinate males lose weight and develop increased basal corticosterone levels compared to dominant males (Blanchard et al. 1995). Several observations also suggest that these subordinate males show changes in dopaminergic tone in the NAc. Subordinate males have decreased dopamine transporter binding and increased D2 receptor binding as well as reduced enkephalin gene expression compared to dominants (Lucas et al. 2004).

Dominance hierarchies can also be observed in social groups of cynomolgus monkeys. Subordinate female monkeys are more vigilant and more likely to spend time alone (Shively et al. 1997). This behavioral phenotype is paired with abnormal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function as well as altered dopamine receptor. Dopaminergic function is sometimes estimated clinically through a haloperidol (a D2 antagonist) challenge (Asnis et al. 1988), as antagonizing D2 receptors facilitates the release of prolactin (Gudelsky and Porter 1980). Subordinate female monkeys had lower prolactin responses to haloperidol than dominant monkeys (Shively 1998), suggesting that D2 function was inhibited. Although these data are not a direct measure of brain D2 function, it is interesting that both subordinate rats and monkeys show evidence of altered D2 receptor function.

Rodent social defeat studies are more controlled than studies focusing on subordinate individuals (because individuals are randomly assigned to stress or control conditions), which makes it easier to establish cause-effect relationships between stress and behavioral/neurobiological responses. In general it appears that stress-induced increases in the activity of VTA dopamine neurons increases the probability of long term changes in behavior following social stress. However, there is growing evidence across a wide range of species that not every individual responds the same way to social stressors. Studies of subordinate individuals could be helpful for providing more insights to individual variation. Studies of subordinates could be considered less controlled because subordinates are not randomly assigned. However, this type of approach may be more closely resemble natural social groups. In addition studying subordinates in more natural social groups may produce more individual variation in behavior, which could be valuable for studying susceptible and resilient phenotypes.

Humans

For many individuals with social anxiety disorders, engaging in social interactions can be an unusually stressful activity. Most studies examining brain function in the context of social anxiety disorders have focused on the amygdala and frontal cortex (Freitas-Ferrari et al. 2010), but some findings suggest that there may be differences in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Male patients with social anxiety disorder were studied using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) 1 minute before making a public speech. Patients with social anxiety disorder had higher levels of activity in ventral striatum (which includes the NAc and caudate putamen) compared to matched controls (Lorberbaum et al. 2004). Adolescents with social anxiety disorder have also been observed to have heightened NAc responses when anticipating a reward in a monetary incentive delay task (Guyer et al. 2011), which involves reacting to cues that signal monetary reward (Knutson et al. 2001). Efforts to link altered activity patterns in ventral striatum to altered dopamine function have yielded inconsistent results, with one report suggesting decreased striatal dopamine reuptake sites (Tiihonen et al. 1997) and a second report suggesting increased striatal dopamine reuptake sites (van der Wee et al. 2008) in patients with social anxiety disorder. Similarly inconsistent results were found in studies examining D2 receptor binding in adult populations with social anxiety phenotypes (Schneier et al. 2000; Schneier et al. 2009). Although it is possible that altered striatal responsiveness observed with fMRI in social anxiety studies is independent of altered dopamine function, it is also possible that current PET scanning techniques are too limited to detect changes in dopamine function (e.g. changes in dopamine release). Most likely it will take a combination of clever behavioral experimentation and pharmacological manipulations to determine whether social anxiety phenotypes are associated with altered dopamine signaling.

In addition to imaging data, there are some limited measurements of molecular signaling pathways in human postmortem brain samples. Most datasets have compared patients with depression using antidepressants to control populations. For example, patients with depression were observed to have higher BDNF protein levels in NAc (Krishnan et al. 2007) and increased phospho-AKT in the VTA (Krishnan et al. 2008) compared to controls. These results illustrate the complexity of the human brain, as increased BDNF in the NAc corresponds with a susceptible phenotype observed in mice while increased phospho-AKT in the VTA resembles the unsusceptible phenotype. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more detailed life history data will be extremely valuable for determining whether stressful experiences induce the same types of changes in mesolimbic dopamine function that has been observed in animal models.

Sex Differences in Mesolimbic Dopamine Responses to Stress

Many (but certainly not all) sex differences in brain function and behavior are mediated by gonadal steroids. Compared to other hypothalamic and limbic pathways, the mesolimbic dopamine system is not usually considered a steroid-sensitive pathway. However, a variety of anatomical and functional data suggest that steroid hormones act on both cell bodies and terminal fields to modulate dopaminergic function. In rats low levels of androgen receptor mRNA were detected in VTA but not NAc (Simerly et al. 1990) which is consistent with observations that testosterone infusions increase c-fos expression in the VTA but not NAc (DiMeo and Wood 2006). However, testosterone infusions into the NAc of male rats can induce conditioned place (Packard et al. 1997). One possible explanation for these contrasting results is that AR expression in the NAc is plastic. In male California mice, winning aggressive encounters increases AR immunoreactivity in the NAc to amounts similar to the medial amygdala (Fuxjager et al. 2010). AR has also been observed in homologous regions of NAc and VTA in several fish (Forlano et al. 2010; Munchrath and Hofmann 2010) and birds (Maney et al. 2001). Estrogen concentrating cells are also present in the NAc and VTA (Pfaff and Keiner 1973). In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry studies suggest that these cells express ERβ but not ERα receptors (Shughrue and Merchenthaler 2001; Creutz and Kritzer 2002). However in other species ERα is also reported in homologous regions to NAc and VTA (Munchrath and Hofmann 2010). Despite relatively low levels of estrogen receptor protein expression in the mammalian mesolimbic dopamine system, there is substantial evidence that behaviors dependent on this system are potently regulated by estradiol (Becker 1999). These effects of estrogens could be indirect, or could possibly be mediated by membrane bound estrogen receptors such as GPR30 which has been identified in the NAc (Hazell et al. 2009).

Sex Differences in Response to Nonsocial Stressors

Many studies have outlined strong sex differences in how the NAc responds to reinforcing stimuli such as drugs of abuse (Wood 2011), primarily in rodents. However, much less is known about whether there are sex differences in how stressful contexts affect NAc function. Here the focus will shift to two behavioral responses that are known to be regulated by the NAc. The chronic mild stress method was developed as an animal model of mood disorders (Wilner 2005) and affects several behaviors that are modulated by the mesolimbic dopamine system. Sucrose preferences are commonly measured as an estimate of anhedonia. Intriguingly, even rodents display hedonic reactions immediately after consuming sucrose that closely resemble responses made by humans and primates (Grill and Norgren 1978; Steiner et al. 2001), and decreased consumption of sucrose following stress is mediated in part by the NAc (Muschamp et al. 2011). However, the effects of stress on sucrose preferences are sometimes inconsistent, and this is reflected in results from studies of sex differences. Chronic mild stress was found to reduce sucrose intake in both male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Grippo et al. 2005) whereas a different study reported that female but not male Sprague-Dawley and Long Evans rats reduced sucrose intake (Konkle et al. 2003). Studies from a third research group have reported that chronic mild stress reduced sucrose intake in both male and female Wistar rats but that the effect was stronger in females (Dalla et al. 2005; Dalla et al. 2008). Social isolation in prairie voles also decreased sucrose preferences in females and males, but the effect was again stronger in females (Grippo et al. 2007). The general pattern that has been reported across lab groups is that both males and female sucrose preferences are sensitive to stress but that on average stronger changes are observed in females.

Stress has also been observed to affect behavior in the forced swim test. In this test, the amount of time an individual spends swimming or floating in a small water-filled cylinder is recorded (Cryan and Mombereau 2004), with floating behavior often interpreted as a behavior related to “despair” (Porsolt et al. 1978). Although it could be argued that floating behavior is a more efficient behavioral response (Nishimura et al. 1988), the forced swim test has been useful for identifying drugs with antidepressant properties. Several molecular pathways in the NAc are known to modulate behavioral responses in the force swim (Pliakas et al. 2001; Shirayama and Chaki 2006). Forced swim testing increases CREB activation in the NAc shell of male rats and inhibition of CREB activity inhibits immobility behavior (Pliakas et al. 2001). Chronic mild stress increased floating behavior in the forced swim test in females but not males, and this sex difference was found to be mediated by ovarian hormones (LaPlant et al. 2009). This study used microarrays to examine the effect of chronic mild stress on gene expression in the NAc and identified several subunits of the NfKB pathway as potential targets that appear to mediate behavioral changes induced by stress. In summary, while there is compelling evidence for sex differences in sucrose preferences and behavior in forced swim tests, less is known about how much sex differences in mesolimbic dopamine function contribute to these behavioral effects.

Sex Differences in Effects of Social Stressors

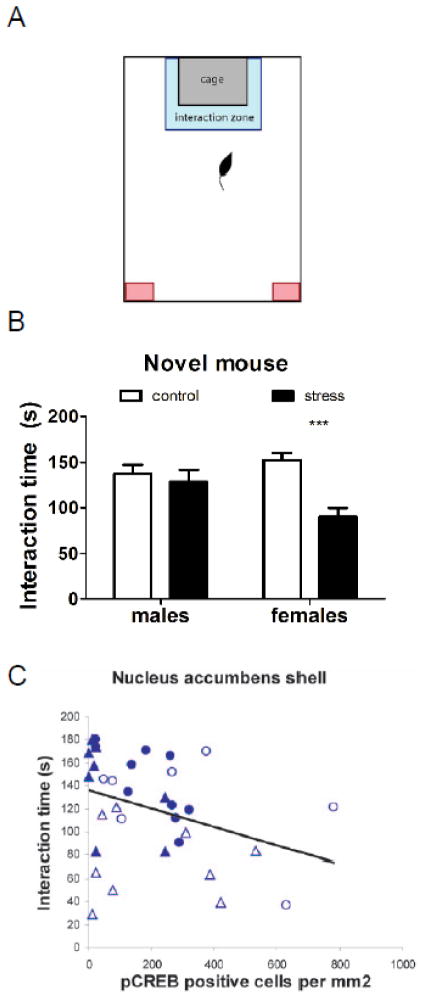

As mentioned previously, the social defeat model has proven to be extremely robust across laboratories. However, a major obstacle has been the inability to study females due to low aggression levels in female rats and mice. However, some rodent species have different social systems which are associated with much higher levels of female-female aggression. The California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) is a monogamous species in which both males and female aggressively defend territories (Ribble and Salvioni 1990). Laboratory studies show that female residents are very aggressive in resident-intruder tests (Davis and Marler 2003; Silva et al. 2010), and show stronger glucocorticoid responses than males after aggressive encounters (Trainor et al. 2010). Three episodes of social defeat across a three day period reduced social interaction behavior in female but not male California mice (Trainor et al. 2011). Defeat also reduced investigation of social odors in habituation-dishabituation tests conducted in the home cage, again with a stronger effect in females compared to males. Interestingly, the effect of defeat on social interaction behavior in California mouse females becomes stronger over a 4 week period. This suggests that a long term change in gene expression or synaptic remodeling may contribute to the observed behavioral changes. Analyses of brain activity immediately after social interaction testing suggested that some of these changes may occur within the NAc.

Brain activity was assessed indirectly using immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated CREB. The activation of CREB can occur through multiple molecular pathways (Fig. 4), such as BDNF signaling or the activation of D1 dopamine receptors, making it a broad marker of cellular activity. In both the NAc shell and core, females exposed to defeat had more pCREB positive cells than control females whereas this difference was absent in males (Fig. 4). In the NAc shell, the number of pCREB positive cells was negatively correlated with social interaction behavior in both males and females. There was no effect of defeat on the number of pERK positive cells in males or females, and the number of pERK positive cells was not correlated with the number of pCREB cells. A similar dissociation between ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the NAc has been observed in several studies examining the effects of cocaine on brain function (Edwards et al. 2007) and behavior (Tropea et al. 2008). Since the binding of BDNF to its receptor leads to phosphorylation of ERK, this result suggests that an increase in BDNF signaling may not be the causal mechanism driving social withdrawal behavior in females. Thus, social defeat in female California mice induces a reduction in social interaction behavior and this behavioral change is associated with changes in the activity of the NAc. These results parallel previous observations described above in male mice. Preliminary data showed that bilateral infusion of 500 ng of the D1 agonist SKF38393 into the NAc shell reduced social interaction behavior in control females (Campi & Trainor unpublished), thus inducing a phenotype similar to that observed in females exposed to defeat. As discussed above, social stress has been observed to increase the activity of VTA neurons, which would be expected to increase dopamine release in the NAc. However, it is not known whether D1 receptors mediate social withdrawal in male mice exposed to defeat, or whether this effect is solely mediated by increased BDNF signaling (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Social interaction behavior in male and female California mice after social defeat. In the apparatus used for testing (A), the interaction zone is indicated by a blue box. Females, but not males exposed to social defeat showed reduced social interaction behavior with a novel same sex mouse (B). *** planned comparison control group versus stress group. The number of pCREB positive cells in the NAc shell was negatively correlated with social interaction time with a novel same sex mouse (C). Filled circles (control males), open circles (stressed males), filled triangles (control females), open triangles (stressed females). Spearman r = −0.37, p < 0.05.

The effect of social stress on mesolimbic dopamine function has also been studied in primates. Male and female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) form dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals showing higher levels of aggressive behaviors and subordinate monkeys receiving more aggressive behaviors (Adams et al. 1985; Deruiter et al. 1994; van Noordwijk and van Schark 1999). One study examined the relationship between behavioral responses to a low dose of cocaine (which increases dopamine release in the NAc) and dominance status. Subordinate monkeys had stronger locomotor responses to cocaine than dominant monkeys (Morgan et al. 2000), which suggests either an increased dopamine response or increased sensitivity to dopamine. A positron emission tomography (PET) study showed that subordinate males had lower D2 receptor binding in basal ganglia than dominants, and that this difference was absent before social hierarchies were formed (Morgan et al. 2002). Decreased D2 receptor binding in basal ganglia as measured via PET was reported in subordinate females compared to dominant females (Grant et al. 1998). Thus it appears that social subordination has similar effects on striatal D2 binding in both male and female cynomolgus monkeys. However, since males and females have not been compared directly, it is not clear whether the effects of subordination are stronger in males versus females. Another question is whether the observed changes in D2 binding occur broadly across the basal ganglia or whether changes in D2 binding are limited to discrete nuclei (resolution of the instruments in these studies could not distinguish subregions such as ventral or dorsal striatum). Interestingly, decreased D2 binding in subordinate monkeys is consistent with observations of elevated pCREB signaling in female California mice exposed to defeat. Activation of post-synaptic D2 receptors reduces expression of cyclic AMP, and would thus be expected to decrease activation of CREB. However, D2 receptors are also expressed on pre-synaptic dopamine neurons and act as autoreceptors inhibiting dopamine release (Wolf and Roth 1990). Based on the methodology used to measure D2 receptor expression in studies of subordinate individuals, it is not possible to determine whether changes in D2 binding affect pre-synaptic neurons, post-synaptic neurons, or both.

Conclusions

The idea that the mesolimbic dopamine system is more than an approach-based system has gained traction as more experimental data document responses to aversive contexts. Observations that certain types of stressors can induce NAc dopamine release would appear to support hypotheses that NAc dopamine signals the salience of events in addition to participating in reward-based learning. The discovery that different populations of VTA dopamine neurons respond differently to appetitive and aversive contexts suggests the possibility that different VTA neurons may modulate either salience or reward learning (or possibly both). As so often occurs in intense debates, (like the nature-nurture debates of the 20th century) there may be more than correct explanation for the function of VTA dopamine neurons.

Data contributing to this debate, such electrophysiological studies of VTA dopamine neurons, come primarily from studies using domesticated male rats and mice. Going forward, it will be essential to study the responses of VTA neurons in females, as this review has highlighted that neurobiological and behavioral responses to stress are frequently sex-dependent. It will also be interesting to confirm whether the altered activity of VTA neurons following social defeat occur in tyrosine hydroxylase positive cells. The effects of easily controlled stressors such as footshock or restraint stress have provided important discoveries. It is also clear that social contexts, especially social defeat, can dramatically alter signaling pathways in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Studying species with different sensory systems or social organizations has the potential to provide novel insights into these relationships, and will be a critical component to future research on mesolimbic dopamine stress responses.

Highlights.

The mesolimbic dopamine system is activated during stress

This review examines how social factors influence dopaminergic stress responses

The ventral tegmental area can induce social withdrawal in rodents

More work is needed in females and in species with different social systems

Acknowledgments

I thank Catherine Marler, Hans Hofmann, and Randy Nelson for guidance and support during my graduate/postgraduate training and beyond. I also thank Elizabeth Adkins-Regan, Karen Bales, Alex Basolo, Kari Benson, Michael Ryan, Charles Snowdon, and Kiran Soma for support and encouragement during early stages of my career. I thank William Mason for helpful conversations, and Katharine Campi, David Dietz, Sarah Heimovics and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. B.C.T. is supported by NIH grants R01 MH085069, R21 MH090392, DOD W81XWH-09-1-0663, and the UC Davis Hellman Fellows program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abercrombie ED, Keefe KA, DiFrischia DS, Zigmond MJ. Differential Effect of Stress on In Vivo Dopamine Release in Striatum, Nucleus Accumbens, and Medial Frontal Cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52:1655–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MR, Kaplan JR, Koritnik DR. Psychosocial influences on ovarian endocrine and ovulatory function in Macaca fascicularis. Physiology & Behavior. 1985;35:935–940. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Stinus L, Lemoal M, Cador M. Social Deprivation Enhances the Vulnerability of Male Wistar Rats to Stressor and Amphetamine-Induced Behavioral Sensitization. Psychopharmacology. 1995;117:116–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02245106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alheid GF, Heimer L. New perspectives in basal forebrain organization of special relevance for neropsychiatric disorders: the striatopallidal amygdaloid and corticopetal components of the substantia innominata. Neuroscience. 1988;27:1–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann SA. A field study of the sociobiology of rhesus monkeys. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1962;102:338–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1495–1497. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Thompson AP, Krenzel E, Teicher MH. Pubertal changes in gonadal hormones do not underlie adolescent dopamine receptor overproduction. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstrom KK, Woodward DJ. Restraint Increases Dopaminergic Burst Firing in Awake Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1832–1840. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstrom KK, Miczek KA, Budygin EA. Increased phasic dopamine signaling in the mesolimbic pathway during social defeat in rats. Neuorscience. 2009;161:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Yu YJ, Curtis JT, Detwiler JM, Insel TR, Wang Z. Nucleus accumbens dopamine differentially mediates the formation and maintenance of monogamous pair bonds. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nn1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnis GM, Sachar EJ, Langer G, Tabrizi MA, Nathan RS, Halpern FS, Halbreich U. Prolactin responses to haloperidol in normal young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1988;13:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(88)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Kelley AE. Discrete neurochemical coding of distinguishable motivational processes: insights from nucleus accumbens control of feeding. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:439–459. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Boone E, Epperson P, Hoffman G, Carter CS. Are behavioral effects of early experience mediated by oxytocin? Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:24. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bowling SL, Rowlett JK, Manderscheid P, Buxton ST, Dwoskin LP. Environmental enrichment attenuates locomotor sensitization but not in vitro dopamine release induced by amphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:397–405. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00413-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrot M, Olivier JDA, Perrotti LI, DiLeone RJ, Berton O, Eisch AJ, Impey S, Storm DR, Neve RL, Yin JC, et al. CREB activity in the nucleus accumbens shell controls gating of behavioral responses to emotional stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11435–11440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172091899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrot M, Wallace DL, Bolaños-Guzman CA, Graham DL, Perrotti LI, Neve RL, Chambliss H, Yin JC, Nestler EJ. Regulation of anxiety and initiation of sexual behavior by CREB in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8357–8362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500587102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassareo V, De Luca MA, Di Chiara G. Differential Expression of Motivational Stimulus Properties by Dopamine in Nucleus Accumbens Shell versus Core and Prefrontal Cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4709–4719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04709.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB. Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1999;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Rudick CN, Jenkins WJ. The Role of Dopamine in the Nucleus Accumbens and Striatum during Sexual Behavior in the Female Rat. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3236–3241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03236.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Zucker I. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IS, Sharpe LG. Social roles in a rhesus monkey group. Behaviour. 1966;26:91–103. doi: 10.1163/156853966x00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Venier IL, Robinson TE. Taste reactivity analysis of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced aphagia: implications for arousal and anhedonia hypotheses of dopamine function. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:36–45. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, McClung CA, DiLeone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, et al. Essential Role of BDNF in the Mesolimbic Dopamine Pathway in Social Defeat Stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharati IS, Goodson JL. Fos responses of dopamine neurons to sociosexual stimuli in male zebra finches. Neuroscience. 2006;143:661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialy M, Kalata U, Nikolaev-Diak A, Nikolaev E. D1 receptors involved in the acquisition of sexual experience in male rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;206:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard DC, Spencer RL, Weiss SM, Blanchard RJ, McEwen B, Sakai RR. Visible burrow system as a model of chronic social stress: behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:117–134. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)e0045-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. Antipredator defensive behaviors in a visible burrow system. J Comp Psychology. 1989;103:70–82. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.103.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondar NP, Boyarskikh UyA, Kovalenko IL, Filipenko ML, Kudryavtseva NN. Molecular Implications of Repeated Aggression: Th, Dat1, Snca and Bdnf Gene Expression in the VTA of Victorious Male Mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield LA, McNally GP. The role of nucleus accumbens shell in learning about neutral versus excitatory stimuli during Pavlovian fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2010;17:337–343. doi: 10.1101/lm.1798810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KC, Haas AR, Meisel RL. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesions in femal hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) abolish the sensitized effects of sexual experience on copulatory interactions with males. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:224–232. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA. Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4894–4899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuon. 2010;68:815–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns-Cusato M, Cusato BM, Daniel A. A new model for sexual conditioning: the ring dove (Streptopelia risoria) J Comp Psychol. 2005;118:111–116. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.119.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun JB. The ecology and sociology of the Norway rat. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon CM, Palmiter RD. Reward without dopamine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10827–10831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10827.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J-L, Covington HE, Friedman AK, Wilkinson MB, Walsh JJ, Cooper DC, Nestler EJ, Han M-H. Mesolimbic dopamine neurons in the brain reward circuit mediate susceptibility to social defeat and antidepressant action. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16453–16458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3177-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carere C, Welink D, Drent PJ, Koolhaas JM, Groothuis TGG. Effect of social defeat in a territorial bird (Parus major) selected for different coping styles. Physiology & Behavior. 2001;73:427–433. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland BJ, Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. Enhanced dopamine uptake in the striatum following repeatedrestraint stress. Synapse. 2005;57:167–174. doi: 10.1002/syn.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter CL, Happe HK, Murrin LC. Postnatal development of the dopamine transporter: A quantitative autoradiographic study. Developmental Brain Research. 1996;92:172–181. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, Tropea TF, Rajadhyaksha AM, Kosofsky BE, Miczek KA. NMDA receptors in the rat VTA: a critical site for social stress to intensify cocaine taking. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:203–216. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutz LM, Kritzer MF. Estrogen receptor-beta immunoreactivity in the midbrain of adult rats: Regional, subregional, and cellular localization in the A10, A9, and A8 dopamine cell groups. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446:288–300. doi: 10.1002/cne.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Mombereau C. In search of a depressed mouse: utility of models for studying depression-related behavior in genetically modified mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:326–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Antoniou K, Drossopoulou G, Xagoraris M, Kokras N, Sfikakis A, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Chronic mild stress impact: Are females more vulnerable? Neuroscience. 2005;135:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Antoniou K, Kokras N, Drossopoulou G, Papathanasiou G, Bekris S, Daskas S, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Sex differences in the effects of two stress paradigms on dopaminergic neurotransmission. Physiology & Behavior. 2008;93:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Fadok JP, Palmiter RD. Requirement of dopamine signaling in the amygdala and striatum for learning and maintenance of a conditioned avoidance response. Learn Mem. 2011;18:136–143. doi: 10.1101/lm.2041211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ES, Marler CA. The progesterone challenge: steroid hormone changes following a simulated territorial intrusion in female. Peromyscus californicus Horm Behav. 2003;44:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deruiter JR, Vanhooff J, Scheffrahn W. Social and genetic-aspects of paternity in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Behavior. 1994;129:203–224. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Craft TKS, Glasper ER, Neigh GN, Alexander JK. 2006 Curt P. Richter award winner: Social influences on stress responses and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:587–603. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, Lecca D. Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz DM, Dietz KC, Nestler EJ, Russo SJ. Molecular mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced structural plasticity. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42(Suppl 1):S69–S78. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMeo AN, Wood RI. ICV testosterone induces Fos in male Syrian hamster brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domjan M. Adult learning and mate choice: possibilities and experimental evidence. Amer Zool. 1992;32:48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stess-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Graham DL, Bachtell RK, Self DW. Region-specific tolerance to cocaine-regulated cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation following chronic self-administration. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25:2201–2213. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott E, Ezra-Nevo G, Regev L, Neufeld-Cohen A, Chen A. Resilience to social stress coincides with functional DNA methylation of the Crf gene in adult mice. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1351–1353. doi: 10.1038/nn.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine MS. Solicitation behavior in the estrous female rat: A review. Hormones and Behavior. 1989;23:473–502. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(89)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Cador M, Robbins TW. Interactions between the amygdala and ventral striatum in stimulus-reward associations: studies using a second-order schedule of sexual reinforcement. Neuroscience. 1989;30:63–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous S, Hammer RP, Jr, Nikulina EM. Short- and long-term effects of intermittent social defeat stress on brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in mesocorticolimbic brain regions. Neuroscience. 2010;167:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipenko ML, Alekseyenko OV, Beilina AG, Kamynina TP, Kudryavtseva NN. Increase of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine transporter mRNA levels in ventral tegmental area of male mice under influence of repeated aggression experience. Molecular Brain Research. 2001;96:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorino DF, Coury A, Phillips AG. Dynamic Changes in Nucleus Accumbens Dopamine Efflux During the Coolidge Effect in Male Rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4849–4855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Marchaterre M, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Distribution of androgen receptor mRNA expression in vocal, auditory, and neuroendocrine circuits in a teleost fish. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:493–512. doi: 10.1002/cne.22233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas-Ferrari MC, Hallak JEC, Trzesniak C, Filho AS, Machado-de-Sousa JP, Chagas MHN, Nardi AE, Crippa JAS. Neuroimaging in social anxiety disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2010;34:565–580. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulford AJ, Marsden CA. Effect of Isolation-Rearing on Conditioned Dopamine Release In Vivo in the Nucleus Accumbens of the Rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70:384–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxjager MJ, Forbes-Lorman RM, Coss DJ, Auger CJ, Auger AP, Marler CA. Winning territorial disputes selectively enhances androgen sensitivity in neural pathways related to motivation and social aggression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12393–12398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001394107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey J, Kow L-M, Huynh W, Ogawa S, Pfaff DW. Temporal and spatial quantitation of nesting and mating behaviors among mice housed in a semi-natural environment. Horm Behav. 2002;42:294–306. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattermann R, Fritzsche P, Neumann K, Al-Hussein I, Kayser A, Abiad M, Yakti R. Notes on the current distribution and the ecology of wild golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Journal of Zoology. 2001;254:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gattermann R, Johnston RE, Yigit N, Fritzsche P, Larimer S, Ö zkurt S, Neumann K, Song Z, Colak Em, Johnston J, et al. Golden hamsters are nocturnal in captivity but diurnal in nature. Biol Lett. 2008;4:253–255. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzke-Kopp LM. The canary in the coalmine: The sensitivity of mesolimbic dopamine to environmental adversity during development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel N, Bale TL. Examining the intersection of sex and stress in modelling neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Kabelik D, Kelly AM, Rinaldi J, Klatt JD. Midbrain dopamine neurons reflect affiliation phenotypes in finches and are tightly coupled to courtship. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8737–8742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811821106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA. Phasic versus tonic dopamine release and the modulation of dopamine system responsivity - a hypothesis for the etiology of schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 1991;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90196-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Shively CA, Nader MA, Ehrenkaufer RL, Line SW, Morton TE, Gage HD, Mach RH. Effect of social status on striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in cynomolgus monkeys assessed with positron emission tomography. Synapse. 1998;29:80–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199805)29:1<80::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Norgren R. The taste reactivity test: I. Mimetic responses to gustatory stimuli in neurologically normal rats. Brain Res. 1978;143:263–279. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Sullivan NR, Damjanoska KJ, Crane JW, Carrasco GA, Shi J, Chen Z, Garcia F, Muma NA, Van de Kar LD. Chronic mild stress induces behavioral and physiological changes, and may alter serotonin 1A receptor function, in male and cycling female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:769–780. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, Sue Carter C. Social isolation induces behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Wu KD, Hassan I, Carter CS. Social isolation in prairie voles induces behaviors relevant to negative affect: toward the development of a rodent model focused on co-occurring depression and anxiety. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:E17–E26. doi: 10.1002/da.20375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Santarelli L, Brunner D, Zhuang X, Hen R. Altered fear circuits in 5-HT1A receptor KO mice. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarraci FA, Kapp BS. An electrophysiological characterization of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons during differential pavlovian fear conditioning in the awake rabbit. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;99:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudelsky GA, Porter JC. Release of Dopamine from Tuberoinfundibular Neurons into Pituitary-Stalk Blood after Prolactin or Haloperidol Administration. Endocrinology. 1980;106:526–529. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-2-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Choate VR, Detloff A, Benson B, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA, Pine DS, Ernst M. Striatal functional alteration during incentive anticipation in pediatric anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Wilkinson LS, Humby T, Inglis W, Kendall DA, Marsden CA, Robbins TW. Isolation Rearing in Rats: Pre- and Postsynaptic Changes in Striatal Dopaminergic Systems. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1998;59:859–872. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell GGJ, Yao ST, Roper JA, Prossnitz ER, O’Carroll A-M, Lolait SJ. Localisation of GPR30, a novel G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor, suggests multiple functions in rodent brain and peripheral tissues. J Endocrinol. 2009;202:223–236. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Guillonneau D, Dantzer R, Scatton B, Semerdjian-Rouquier L, Le Moal M. Differential effects of inescapable footshocks and of stimuli previously paired with inescapable footshocks on dopamine turnover in cortical and limbic areas of the rat. Life Sciences. 1982;30:2207–2214. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Cullinan WE. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2003;24:151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotsenpiller G, Wolf ME. Baclofen attenuates conditioned locomotion to cues associated with cocaine administration and stabilizes extracellular glutamate levels in rat nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2003;118:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00951-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton CL, Garner JP, Mench JA. Effects of a running wheel-igloo enrichment on aggression, hierarchy linearity, and stereotypy in group-housed male CD-1 (ICR) mice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2008;115:90–103. [Google Scholar]