Abstract

Mutations in the transcription factors PROP1 and PIT1 (POU1F1) lead to pituitary hormone deficiency and hypopituitarism in mice and humans. The dysmorphology of developing Prop1 mutant pituitaries readily distinguishes them from those of Pit1 mutants and normal mice. This and other features suggest that Prop1 controls the expression of genes besides Pit1 that are important for pituitary cell migration, survival, and differentiation. To identify genes involved in these processes we used microarray analysis of gene expression to compare pituitary RNA from newborn Prop1 and Pit1 mutants and wild-type littermates. Significant differences in gene expression were noted between each mutant and their normal littermates, as well as between Prop1 and Pit1 mutants. Otx2, a gene critical for normal eye and pituitary development in humans and mice, exhibited elevated expression specifically in Prop1 mutant pituitaries. We report the spatial and temporal regulation of Otx2 in normal mice and Prop1 mutants, and the results suggest Otx2 could influence pituitary development by affecting signaling from the ventral diencephalon and regulation of gene expression in Rathke's pouch. The discovery that Otx2 expression is affected by Prop1 deficiency provides support for our hypothesis that identifying molecular differences in mutants will contribute to understanding the molecular mechanisms that control pituitary organogenesis and lead to human pituitary disease.

Keywords: Ames dwarf, Snell dwarf, PROP1, POU1F1, gonadotrope, pituitary development

studies of pituitary development have focused on identification of signaling pathways that are necessary for induction of the pituitary primordium known as Rathke's pouch and transcription factors that activate hormone gene expression (reviewed in Refs. 27, 47). There are many other critical processes in pituitary organogenesis, including cell migration, coordinating the transition from proliferation to differentiation, establishing connections between cells to form functional multicellular networks, development of vasculature including the hypophyseal portal system, and establishing connections with the hypothalamic neurons that regulate hormone secretion (5, 11, 63). Identification of genes involved in these processes not only would be a significant step forward for understanding the fundamentals of pituitary organogenesis but could also uncover candidate genes for cases of pituitary hypoplasia or dysfunction that currently remain elusive. Pituitary stalk disruption is an important cause of hypopituitarism, and while some congenital cases could be attributable to birth trauma or traumatic brain injury, others are likely to be genetic, and the molecular mechanisms remain to be defined (9, 61).

Mouse models of hypopituitarism have been invaluable for enhancing the understanding of basic pituitary gland development and uncovering the basis for human pituitary disease, yet they have not been heavily exploited for discovering differences in gene expression. A comparison of gene expression in Prop1 and Pit1 mutants would be ideal for identifying new candidate genes. The Prop1df/df mutants, also known as Ames dwarfs, carry an inactivating S83P missense mutation, and the Pit1dw/dw mutants, known as Snell dwarfs, have a W261C missense mutation leading to loss of function (13, 56, 64, 80). These nonallelic mutants have many similar features. Both mutants have multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (MPHD) with little or no GH, PRL, or TSH, a reduction in circulating LH and FSH, and adult pituitary hypoplasia (8, 16, 84). Because of the similar hormone deficiencies, both mutants are the same size as their littermates at birth and begin to display obvious signs of growth insufficiency at ∼2 wk of age. By adulthood, the mutant mice are approximately one-third to one-fourth the size of their littermates. Comparative studies have uncovered several important differences in pituitary gland development between the two mutants (37, 89, 90). Differences are expected because Prop1 expression is detectable before Pit1, and Prop1 would likely have many downstream target genes besides Pit1 (4, 36). Thus, differences in gene expression between Prop1 and Pit1 mutants could reveal specific actions of each gene.

The developmental onset of anterior pituitary hypoplasia, organ morphology, and vascularization are different in Prop1 and Pit1 mutants (36, 89, 90). Hypoplasia of the anterior lobe and pituitary gland dysmorphology are apparent in the Prop1-deficient mice at embryonic day 14.5 (e14.5), although the overall volume of the organ is similar to normal mice until postnatal day 1 (P1). This phenotype is attributed to the failure of precursor cells to migrate away from the proliferative zone and colonize the anterior lobe, causing the striking dysmorphology, decreased cell proliferation, and increased cell death. In contrast, the pituitaries of Pit1-deficient mice are morphologically indistinguishable from normal mice from e14 through birth. Prop1 mutant pituitaries are poorly vascularized, while those of Pit1 mutant mice appear normal. These differences suggest several biological processes are likely to be regulated by Prop1 but not Pit1.

To identify the Prop1- and Pit1-specific target genes that guide pituitary development, we used gene expression microarrays to compare the transcripts in normal, newborn mouse pituitaries with those of Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw mutants. We discovered that the homeobox transcription factor gene Otx2 has uniquely altered expression in Prop1 mutants. The developmental regulation of Otx2 expression in normal mice suggests that it could have roles in development of the hypothalamus and pituitary stalk, as well as Rathke's pouch derivatives, explaining the requirement for OTX2 for normal pituitary function in mouse and human (59). The differentially expressed genes reported here constitute a resource of candidate genes for roles in pituitary development and cases of MPHD of unknown etiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Ames dwarf mice (Prop1df/df), originally obtained from Dr. A. Bartke (Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL) from a noninbred stock (DF/B), and Snell dwarf mice (Pit1dw/dw), originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory from an inbred stock (DW/J) (Bar Harbor, ME), have been maintained as colonies at the University of Michigan through heterozygous matings. The morning after conception is designated e0.5 and the day of birth is designated as P1. All mice were housed in a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle in ventilated cages with unlimited access to tap water and Purina 5020 chow. All procedures using mice were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guidelines of the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

PCR genotyping.

The genotypes of Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw mice were determined as described (31, 36).

Isolation of total RNA from newborn pituitaries.

Pituitaries were collected, stored, homogenized, and RNA isolated as described (88). RNA was isolated from individual pituitaries from Ames wild-type, Ames Prop1df/df, Snell wild-type, and Snell Pit1dw/dw P1 pituitaries for validation by RT quantification PCR (RT-qPCR). To assess RNA quality for the microarray, total RNA was analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) in the UMCCC Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) and cDNA Microarray Core to visualize and quantitate 18S and 28S ribosomal bands. UV spectrophotometry was used to assess the quality and concentration of total RNA for RT-qPCR.

Microarray analysis.

Pituitary gene expression was determined with Mouse Genome 430 2.0 GeneChip oligonucleotide arrays (Affymetrix). Total RNA (1 μg) from three pooled pituitary tissue were used. Amplification of mRNA samples was performed using the Ovation RNA Amplification System (NuGENE, San Carlos, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Synthesis of cRNA, hybridization to chips, and washes were performed in the University of Michigan Affymetrix and cDNA Microarray Core according to the manufacturer's protocol and as described previously (38). RNA samples were processed together, pooling three P1 pituitaries into each RNA sample and then collecting five RNA pooled samples for each of the four experimental groups (Ames background wild type, Ames background Prop1df/df, Snell background wild type, and Snell background Pit1dw/dw). After hybridization, GeneChips were scanned at 1.5-μm density with GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix).

Data analysis.

Data analysis was performed in the University of Michigan Affymetrix and cDNA Microarray Core as previously described (44, 88). Probe-sets were remapped with Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute probe-sets (21). Differentially expressed genes were detected by fitting a gene-wise linear model to the data and computing contrasts of interest. Significance for each comparison was calculated using a nested F-test, which is simply a way to determine which comparisons are significant when there may be more than one significant comparison (79). Testing for overrepresented gene ontology terms was performed using a conditional hypergeometric model according to Alexa et. al., 2006 (3). The unadjusted P value of 0.05 was adjusted for multiplicity using false discovery rate (10). We used RT-qPCR to validate gene expression changes for genes that exhibited a similar fold change in Prop1 mutants vs. wild type and in the Prop1 mutants vs. Pit1 mutants.

Heat maps were created with differentially expressed genes between each of the groups, which were determined by fitting linear models using the LIMMA package from BioConductor. The genes that showed at least a twofold difference and a P value of 0.05 were included. A distance matrix was created using Euclidean distances or the square distance between two samples and then clustered using hierarchical clustering from the hclust function in the “base R” “stats” package.

RT-qPCR.

Synthesis of cDNA and real-time PCR was carried out as described (88). Expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH served as an internal control for each RNA sample. The fold change values and standard deviations were calculated as described (57, 88).

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization.

Timed pregnancies were produced using natural matings of sexually mature females and males. Collected embryos and P1 heads were fixed for 2–4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2) at room temperature, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. Six-micrometer-thick sections were prepared for immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Mengshang Qiu (previously of Dr. John Rubenstein laboratory, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) provided a plasmid-containing mouse Otx2 genomic sequence in pBlueskriptSK-. The Otx2 containing plasmid was linearized with BamHI and labeled with T7 polymerase. The probe was diluted 1:100 and hybridized at 50°C. All riboprobes were generated and labeled with digoxigenin and precipitated with nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) following previously described methods (20, 82).

Pituitary cell populations were examined by immunohistochemistry with antibodies against pituitary hormone markers. Immunostaining for the pituitary hormones was performed with polyclonal antisera against LHβ (1:1,500) and ACTH (1:100, which reacts with POMC as well as its cleavage product ACTH) (National Hormone and Peptide Program, UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA). After antigen retrieval with a 10 min 0.01M citrate boil, immunostaining of pituitary gland transcription factor proteins was performed with antisera against NR5A1 at a 1:1,500 dilution (provided by Dr. Ken-Ichirou Morohashi, National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki, Japan), TPIT used at a dilution of 1:1,000 (Provided by Dr. Jacques Drouin, Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), and OTX2 used at a dilution of 1:1,000 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). All sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibodies for rabbit and guinea pig (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and detected with either the tyramadine signal amplification (TSA) fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) kit (according to the manufacturer's protocol, Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA), or a streptavidin-conjugated Cy2 fluorophor (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Gene pathway building.

Genomatix Bibliosphere Software was used to generate gene networks from microarray data (http://www.genomatix.de). Bibliosphere search was based set on the lowest level Co-citation Filter with the most recent publications on April 2, 2008.

RESULTS

Experimental design for microarray analysis of gene expression.

We selected newborn (P1) pituitaries as a source of tissue for microarray analysis of gene expression instead of embryonic stages at which Prop1 and Pit1 transcription are first initiated for several reasons. Many effects of Prop1 and Pit1 on gene expression can be detected at P1 (89, 90). The size of a P1 pituitary gland is sufficient to provide enough RNA for microarray analyses with limited pooling, and animal use was minimized because mother mice could be bred multiple times. P1 pituitaries were dissected from newborns produced from heterozygote matings, and individuals were genotyped. We pooled pituitaries from three newborn mice of the following genotypes for RNA preparation: DF/B-Prop1df/df, DF/B-Prop1+/+, DW/J-Pit1dw/dw, and DW/J-Pit1+/+. Five independent samples of total RNA for each experimental group were collected and analyzed using Affymetrix microarray technology.

Global analysis of gene expression changes.

The raw microarray expression values were fit to a principal components analysis (PCA) and plotted (data not shown). The results indicate that the greatest amount of difference in gene expression exists between the two strains (DF/B and DW/J). Among the four samples: DW/J-Pit1dw/dw, DW/J-Pit1+/+, DF/B-Prop1+/+, DF/B-Prop1df/df, the mutant and wild-type samples from within a strain were more similar to each other than the two wild types were comparing across strains. To understand the nature of the strain-specific differences in pituitary gene expression, we identified biological processes that differed between the two wild-type strains using overrepresented gene ontology (GO) terms. A total of 43 GO terms were identified with unadjusted P values of <0.01 between the background strains DF/B and DW/J. (Table 1). It is intriguing that the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling pathway, blood vessel development, and grooming behavior are among the strain-specific biological processes terms.

Table 1.

Biological processes affected by genetic background

| GO Term | Description | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0006814 | sodium ion transport | 0.001 |

| GO:0009887 | organ morphogenesis | 0.001 |

| GO:0048010 | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling pathway | 0.001 |

| GO:0035295 | tube development | 0.001 |

| GO:0006898 | receptor-mediated endocytosis | 0.001 |

| GO:0001568 | blood vessel development | 0.001 |

| GO:0032501 | multicellular organismal process | 0.001 |

| GO:0006811 | ion transport | 0.001 |

| GO:0007166 | cell surface receptor linked signal transduction | 0.001 |

| GO:0007625 | grooming behavior | 0.001 |

| GO:0048878 | chemical homeostasis | 0.001 |

| GO:0001654 | eye development | 0.001 |

Biological processes differentially expressed in Prop1+/+ (DF/B) relative to Pit+/+ (DW/J). GO, Gene Ontology.

Individual gene expression differences can be visualized by plotting the genes with at least a twofold difference in expression between the two mutants and the two wild-type strains (Fig. 1A). A total of 524 genes are differentially expressed by at least twofold between the two mutants. A similar degree of differential expression is detected by comparing the two wild types to each other: 418 genes. Fewer differentially expressed genes are detected in comparing the mutants to their normal littermates. There are 118 total genes that are differentially expressed in Prop1 mutants compared with their wild-type littermates, and a total of 85 that are differentially expressed in Pit1 dwarfs compared with wild type. The two mutants share a total of 46 genes that are differentially expressed relative to their wild-type littermates and in the same direction and at the same magnitude (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Differential gene expression in Prop1 and Pit1 mutants. A: heat maps display differentially expressed genes with a significance of P < 0.05 and a fold change of at least 2. Intensity of expression is represented by a color scale where red has the lowest expression and green has the highest expression. Comparison of Prop1df/df with Pit1dw/dw reveals 524 genes with altered expression with a fold change of at least 2. The 2 wild-type stocks (Prop1+/+ and Pit1+/+) differ by 418 genes. Sixty-eight genes differ between Prop1df/df and Prop1+/+ 68 genes, and 53 differed between Pit1+/+ and Pit1dw/dw. B: a Venn diagram illustrates the total number of genes with significantly different expression in Prop1 mutants relative to wild type (left circle) and Pit1 mutants relative to wild type (right circle) out of 6,823 surveyed probe sets. 46 genes exhibited similar a degree of differential expression in both Prop1 and Pit1 dwarfs relative to their wild-type controls (intersection of the 2 circles).

The set of genes with altered expression in both mutants includes expected and novel genes. We anticipated Pit1-dependent genes, including specific products of somatotropes, lactotropes, and thyrotropes, to exhibit reduced expression in pituitaries of both Pit1 and Prop1 newborn mutants relative to wild-type littermates (4, 12, 37, 80, 91). For example, Tshb, thyrotropin releasing hormone receptor (Trhr), and growth hormone releasing hormone receptor (Ghrhr) RNA levels were significantly decreased in the Prop1 and Pit1 dwarfs compared with their wild-type littermates. Most of the novel genes with differential expression are decreased in the two mutants compared with wild types (Table 2). The only gene whose expression is elevated significantly in both mutants is Nr5a1, also known as SF1, a nuclear hormone receptor expressed in pituitary gonadotropes that is important for transcription of Lhb, Fshb, and the gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor, Ghrhr (30, 40, 48).

Table 2.

Expression changes in both dwarf mutants

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Prop1df/df |

Pit1dw/dw |

||

| Prop1+/+ | Pit1+/+ | ||

| Novel Genes | |||

| Pappa2 | pappalysin 2 | −4.66 | −12.21 |

| Rxrg | retinoid X receptor gamma | −3.84 | −5.50 |

| Gnmt | glycine-N-methyltransferase | −2.77 | −4.06 |

| Igsf1 | immunoglobulin superfamily, memember 1 | −2.60 | −3.25 |

| Plac8 | placenta-specific 8 | −2.36 | −2.73 |

| C77370 | expressed sequence C77370 | −2.35 | −2.64 |

| Padi2 | peptidyl arginine deiminase, type II | −2.31 | −2.91 |

| Cyp27a1 | cytochrome P450, family 27, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 | −2.08 | −3.03 |

| Htatsf1 | HIV TAT specific factor 1 | −1.91 | −2.79 |

| Galntl1 | UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine:polypeptide | −2.23 | −2.38 |

| N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-like 1 | |||

| Entpd3 | ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 3 | −2.14 | −2.41 |

| Angptl6 | angiopoietin-like 6 | −2.14 | −2.50 |

| Nqo1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | −1.92 | −2.20 |

| Brunol6 | bruno-like 6, RNA binding protein | −1.95 | −2.31 |

| A930004K21Rik | expressed sequence AI593442 | 1.85 | 1.92 |

| Expected Genes | |||

| Ghrhr | growth hormone releasing hormone receptor | −9.00 | −35.00 |

| Tshb | thyroid stimulating hormone, beta subunit | −4.38 | −32.67 |

| Trhr | thyrotropin releasing hormone receptor | −2.08 | −9.00 |

| Nr5a1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 1 | 2.03 | 2.58 |

Fold change in expression between genotype 1 (top) and genotype 2 (bottom), i.e., negative number means expression is reduced in genotype 1 relative to genotype 2.

Pituitary transcription factor expression in Prop1 and Pit1 mutant mice.

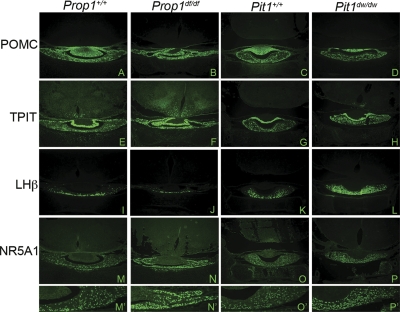

Both mutants have reduced circulating gonadotropins, yet Nr5a1 transcripts are elevated in the pituitary gland (8, 73, 84). The increase in Nr5a1 expression was expected because of absent antagonizing effects of Pit1 in the mutants (23). If Pit1 were the only factor leading to increased Nr5a1 expression, however, the degree of elevation would be similar in both mutants, and it is not (Table 2). The T-box transcription factor TPIT is necessary for suppression of ectopic Nr5a1 expression and ectopic gonadotrope differentiation (70). TPIT activates the transcription of Pomc in corticotropes and melanotropes and hence the production of ACTH and MSH (55). To determine whether alterations in Tpit expression contributed to the elevation in Nr5a1 transcription we carried out immunostaining for TPIT and POMC, and we found similar expression in the Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw dwarf mutants and in their normal littermates at P1 (Fig. 2, A–H). NR5A1 immunostaining is expanded in the anterior pituitary glands of both the Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw dwarf mutants (Fig. 2, N and P), relative to their normal littermates (Fig. 2, M and O), and the increase is more profound in Pit1 mutants. Thus, altered Tpit expression does not appear to contribute to the elevation in Nr5a1 expression in either mutant. Furthermore, unknown factors that are lacking in Prop1 mutants must contribute to the profound elevation of Nr5a1 and LHβ (Fig. 2L) in Pit1 mutants.

Fig. 2.

Differential effects of Pit1 and Prop1 deficiency on gonadotropes but not corticotropes. Coronal sections (×100) of P1 Prop1 mutants, Pit1 mutants, and their wild-type littermates were examined by immunohistochemistry for pituitary hormones and selected transcription factors. POMC immunoreactivity appeared similar in both mutants and their wild-type littermates (A–D). TPIT immunoreactivity was also unaffected (E–H). NR5A1 is expanded in the Prop1 and Pit1 mutants (M–P and M′–P′), but LHβ is decreased only in the Prop1 mutant (U–X).

Biological processes represented by differentially expressed genes.

To identify possible Prop1-specific biological processes we searched for significantly overrepresented GO terms among the genes that were differentially expressed between Prop1 and Pit1 mutants (Table 3). There are 17 GO terms that had unadjusted P values of < 0.05. Among these are five biological processes that were anticipated to exhibit differential expression based on prior knowledge of Prop1 action: tissue development and remodeling, frizzled signaling pathway (14, 49, 69), organ morphogenesis (36, 89), and anterior/posterior patterning (73). Some of the novel processes identified by overrepresentation of GO terms may be mechanistically relevant to Prop1 molecular actions including vesicle-mediated transport and gland development.

Table 3.

Multiple processes altered specifically in Prop1df/df pituitary glands

| GO Term | Description | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0042445 | hormone metabolism | 0.001 |

| GO:0001501 | skeletal development | 0.002 |

| GO:0048511 | rhythmic process | 0.004 |

| GO:0016192 | vesicle-mediated transport | 0.009 |

| GO:0048732 | gland development | 0.011 |

| GO:0009888* | tissue development | 0.023 |

| GO:0051216 | cartilage development | 0.024 |

| GO:0007222* | frizzled signaling pathway | 0.026 |

| GO:0017157 | regulation of exocytosis | 0.031 |

| GO:0046849 | bone remodeling | 0.031 |

| GO:0048771* | tissue remodeling | 0.036 |

| GO:0000160 | two-component signal transduction system | 0.041 |

| GO:0001658 | ureteric bud branching | 0.041 |

| GO:0006029 | proteoglycan metabolism | 0.041 |

| GO:0009887* | organ morphogenesis | 0.042 |

| GO:0009966 | regulation of signal transduction | 0.043 |

| GO:0009952* | anterior/posterior pattern formation | 0.044 |

Biological processes expected to be changed based on previous data.

Prop1-specific changes in gene expression.

We used RT-qPCR to verify differential expression of nine novel genes that appeared to be altered specifically in Prop1 mutants (Table 4). Each RT-qPCR fold change was based on a sample size of four (n = 4). The internal control of GAPDH expression remained relatively constant between the four experimental groups. In each case, a greater change in expression was evident by qPCR than by the expression microarray (93). It is not uncommon for microarrays to underestimate differences in gene expression due to the limited dynamic range of the chip.

Table 4.

Validation of Prop1-specific changes in gene expression

| Fold Change |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Microarray | qPCR | |

|

Prop1df/df |

Prop1df/df |

Prop1df/df |

||

| Pit1dw/dw | Prop1+/+ | Prop1+/+ | ||

| Sult1e1 | sulfotransferase family 1E, member 1 | 16.7 | 9.0 | 212.3 |

| Cbr2 | carbonyl reductase 2 | 19.2 | 3.6 | 14.1 |

| Adamdec1 | ADAM-like, decysin 1 | 14.9 | 8.4 | 12.9 |

| Otx2 | orthodenticle homolog 2 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 4.6* |

| Hey1 | hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif 1 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.3* |

| Cldn10 | claudin 10 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2* |

| Lbxcor1 | ladybird homeobox 1 homolog corepressor 1 | −2.3 | −2.5 | −3.3* |

| Rgs2 | regulator of G-protein signaling 2 | −4.0 | −2.1 | −4.8 |

| Cart | cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript | −4.0 | −4.0 | −21.4 |

Genes with reported expression in e12.5–e14.5 mouse pituitary gland.

The expression of three genes is reduced in the Prop1 mutant relative to wild-type littermates, suggesting that Prop1 normally activates them, as it does for Pit1 (66, 80). The reduction in expression of these genes in Prop1 mutants compared with wild-type ranges from >21-fold for Cart (cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript) to three- to fourfold for Rgs2 (Regulator of G protein signaling 2), and Lbxcor1 or Corl1 (Ladybird homeobox 1 homolog co-repressor 1 or Co-repressor for Lbx1) (Table 4).

The majority of these putative Prop1-specific targets (6/9) exhibit elevated expression in the mutant, ranging from >200-fold to twofold (Table 4). Thus, Prop1 normally represses these genes, similar to the role of Prop1 in silencing Hesx1 expression (36, 66). Most of these putative Prop1 target genes have never been studied in the pituitary gland. However, pituitary expression of Hey1 (Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif 1) and Otx2 (orthodenticle homolog 2) has been reported (59, 74). Hey1 has not been studied extensively in the pituitary, but Prop1 is essential for Notch signaling, and Hey1 is a potential downstream effector of this pathway, suggesting that Hey1 merits further analysis (72).

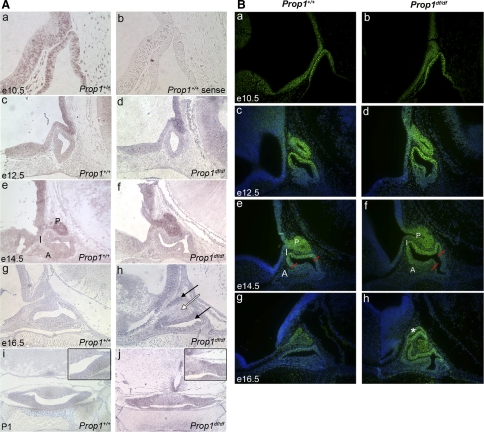

Spatial and temporal regulation of Otx2 expression in developing pituitary gland.

Little is known about the spatial and temporal regulation of Otx2 expression, other than its detection at e12.5 in the mouse pituitary gland (78). If Prop1 were a direct repressor of Otx2, then we would expect Otx2 expression to be present in the dorsal aspect of Rathke's pouch and to wane in normal mice as Prop1 expression peaks at e12.5, and we would expect Otx2 expression to persist in Rathke's pouch through e14.5 in Prop1 mutants, similar to the effects of Prop1 deficiency on Hesx1 expression (36). To explore this idea we analyzed the expression of Otx2 throughout pituitary gland development in normal and Prop1 mutant mice using both in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining.

Otx2 transcripts and protein are normally detectable at e10.5 in both the ventral diencephalon, from which the posterior pituitary lobe develops, and Rathke's pouch (Fig. 3, A and B), indicating both intrinsic and extrinsic effects of Otx2 on pituitary development are possible. No transcripts are detected with the Otx2 sense control probe (Fig. 3Ab), and no OTX2 immunoreactivity is detected in the absence of OTX2 antibody (data not shown). By e12.5 Otx2 transcripts are undetectable in Rathke's pouch, but transcription persists in the region of the ventral diencephalon that acts as a signaling center for pouch growth by expressing fibroblast growth factors 8 and 10 (FGF8, FGF10) and bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) (Fig. 3Ac) (14, 26, 32, 86). This pattern of Otx2 transcripts, present in the ventral diencephalon but absent in the pouch, continues at e14.5 (Fig. 3Ae). No Otx2 transcripts are detected in the normal ventral diencephalon or any of the lobes of the pituitary gland at e16.5 or P1 (Fig. 3A, g and i). OTX2 protein exhibits perdurance: immunoreactivity is still detectable in the intermediate lobe at e12.5 and e14.5 even though the transcripts have faded (Fig. 3B, c and e). By e16.5 OTX2 immunoreactivity is reduced in both the posterior and intermediate lobes of normal mice (Fig. 3Bg). The spatial and temporal pattern of Otx2 expression reveals the potentially important expression of Otx2 in the ventral diencephalon and posterior pituitary lobe in addition to transient, early expression in Rathke's pouch.

Fig. 3.

A, B: developmental regulation of Otx2 transcript and OTX2 protein in wild-type and Prop1df/df pituitary gland. A: wild-type and Prop1df/df pituitary sections from e10.5 to P1 were analyzed using in situ hybridization for the transcript Otx2. Sections a–h are mid-sagittal (×200) and sections in i and j are coronal (×100). The forming pituitary gland of an e10.5 wild type shows expression in the ventral diencephalon and in the invaginated oral ectoderm (a). There is no evidence of transcript using the sense control of the Otx2 probe (b). Similar expression of Otx2 is seen in the ventral diencephalon of the e12.5 wild type (c) and Prop1df/df (d). Otx2 expression is present in the ventral diencephalon and the forming posterior lobe in wild type (e) and mutant (f). Otx2 expression is absent in wild type (g) but present in the ventral diencephalon, anterior, and intermediate lobe of Prop1 mutants (h) at e16.5. Otx2 transcripts are undetectable in wild-type pituitary gland (i) at P1, but present in the anterior and intermediate lobes of the Prop1 mutant (j). A, anterior lobe; I, intermediate lobe; P, posterior lobe. B: wild-type and Prop1df/df pituitary sections from e10.5 through e16.5 were analyzed using fluorescent immunohistochemistry to the protein OTX2. All sections are mid-sagittal (×200). OTX2 immunostaining is detected in the ventral diencephalon and in the invaginated oral ectoderm of an e10.5 wild type (a) and Prop1 mutant (b). At e12.5, the OTX2 protein is still present in the dorsal region of the lumen and the forming posterior lobe in both wild type (c) and mutant (f). OTX2 protein is restricted to the forming poster lobe (P) and forming intermediate lobe (I) at e14.5 in the wild types (e). However, the OTX2 protein is expanded ventrally into the forming anterior lobe (a) in the mutant (f). OTX2 protein is present throughout the dysmorphic intermediate lobe (white asterisk) and the posterior lobe of Prop1 mutants at e16.5 (h), but has very limited expression in the posterior lobe of the wild-type pituitaries (g).

The temporal and spatial patterns of Otx2 transcripts and protein are similar in Prop1 mutants and wild-type mice at e10.5, e12.5, and e14.5 (compare Fig. 3B, a and b; Fig. 3A, c and d; Fig. 3B, c and d; Fig. 3A, e and f). OTX2 immunoreactivity is slightly expanded in the Prop1 mutant at e14.5, when the dysmorphology of the mutant becomes evident (Fig. 3B, e and f) (36). By e16.5, both Otx2 transcription and protein accumulation are elevated in Prop1 mutant intermediate lobes relative to wild type (compare Fig. 3A, g and h; Fig. 3B, g and h). At P1 ectopic Otx2 expression is evident in patches of both the intermediate and anterior lobes (black arrows) (compare Fig. 3A, i and j). No ectopic expression is detectable in the posterior lobe of Prop1 mutants (white arrow) at e16.5 (Fig. 3Ah). Thus, Prop1 deficiency causes abnormalities in Otx2 expression in Rathke's pouch derivatives after Prop1 expression has waned in wild-type mice. It does not cause abnormalities in Otx2 expression in the ventral diencephalon or posterior lobe. Although we cannot rule out direct effects, Prop1 deficiency appears to affect Otx2 expression indirectly.

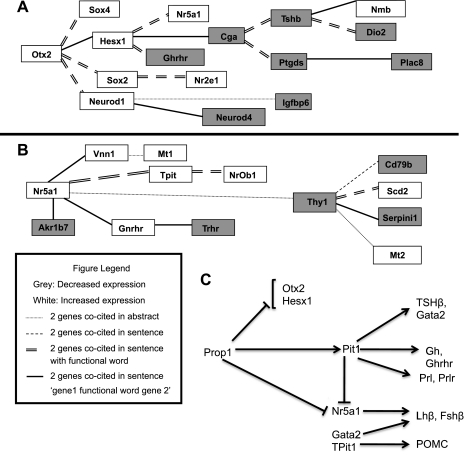

Gene networks potentially regulated by Pit1 and Prop1.

We identified a number of putative gene networks amongst the genes differentially expressed in mutants relative to wild type using Bibliosphere software by Genomatix (http://www.genomatix.de), which uses scientific literature to build networks of potentially interacting genes. We selected two compelling networks that are anchored by Otx2 and Nr5a1, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B), for presentation of significant differentially expressed genes. Both gene networks include Nr5a1. We present an updated representation of the likely upstream and downstream factors for Prop1 in the developing mouse pituitary gland (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

A, B: potential Prop1 and Pit1 gene expression networks. Pathways generated using Genomatix Bibliosphere software based on genes differentially expressed in Prop1df/df relative to wild type and Pit1dw/dw relative to wild-type microarrays. White boxes signify increased gene expression and grey boxes signify decreased gene expression. Connecting lines are based on Genomatix Bibliosphere Co-citation Filter, which connects genes based on co-citation frequency and specificity levels. The following lines represent the different levels of specificity: dotted line represents 2 genes co-cited within an abstract; dashed line represents 2 genes co-cited in the same sentence; double-dashed line represents 2 genes co-cited in the same sentence with a functional word; Single, thick line represents 2 genes co-cited in the same sentence with a functional word but restricted to the order, “gene 1 function word gene 2”. Network of genes with altered expression in Prop1 mutant related to increased Otx2 expression (A) and increased Nr5a1 expression (B). C: Prop1-directed gene pathway. Prop1 is upstream of Pit1. Pit1 is required for expansion and differentiation of a lineage of hormone producing cells in the pituitary, which includes somatotropes (GH), thyrotropes (TSH), and lactotropes (PRL). Both Prop1 and Pit1 are necessary for inhibiting the expression of Nr5a1, which in turn, along with Gata2, causes differentiation of the gonadotropes (LHβ and FSHβ). Otx2 and Hesx1 repress the expression of Prop1 at the appropriate time during development.

Otx2 expression is increased specifically in Prop1 mutants (Table 4), and it is the anchor for a novel pituitary gene network (Fig. 4A). The increase in Otx2 expression is associated with elevated Hesx1 expression in the microarray and in Prop1 mutant mice (36). The increase in Hesx1 transcripts is associated with decreases in Cga and Tshb expression. It is intriguing that expression of the stem cell markers Sox2 (SRY-box containing gene 2) and Nr2e1 (nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group E, member 1)(33, 77) are increased, given that Prop1 mutants exhibit difficulty transitioning from the proliferative zone to differentiation zone (89).

Nr5a1 expression is elevated in both Prop1 and Pit1 mutants (Fig. 2) (23, 73), and it anchors a gene network that contains Gnrhr, a known target of Nr5a1 (Fig. 4B) (43). Another network member is thyrotropin releasing hormone receptor (Trhr), which is important for the production of TSH and PRL in the pituitary gland (95). Increased Nr5a1 expression leads to increased transcription of Tpit and Nr0b1 (nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 1), also known as Dax1, which can have either antagonistic (51, 94) or cooperative relationships with Nr5a1 depending on the context (67).

DISCUSSION

The phenotypic similarities and differences between pituitary development and function in Prop1 and Pit1 mutants create a unique opportunity to identify new genes and pathways that may be direct targets of Prop1 and Pit1 action by comparative gene expression profiling. We have focused on genes that are differentially expressed in the Prop1df/df mutant and wild type, along with genes differentially expressed between the Prop1df/df mutant and the Pit1dw/dw mutant, through gene expression microarray analysis. We present a manageably sized collection of genes affected specifically by Prop1, and an inventory of probable Prop1-specific biological processes. In addition, we uncovered a list of novel genes that are affected by both mutants, and serendipitously, a cadre of genes whose pituitary expression at birth is strongly influenced by genetic background.

Strain-specific differences in pituitary gene expression.

The greatest degree of difference in gene expression exists between the two wild-type strains (DF/B and DW/J). We identified numerous biological processes underlying this unexpected finding. The reason for these gene expression differences is not clear, but some could be attributable to differences in gestation time, and thereby maturity of the newborn pups. Gestation time in mice varies from 18 to 22 days, and the strain of mouse and size of the litter both influence the gestation time (39). The anterior lobe of the pituitary gland grows laterally, producing an elongated shape in the coronal plane, in late gestation and the neonatal period. The DF/B strain appears to have more elongated pituitary gland at birth than the DW/J strain. Whatever mechanism underlies the strain specific differences in normal pituitary gland gene expression, the sheer abundance of them at birth underlines the importance of using normal littermate controls.

We were most intrigued by the strain-specific effects on the biological processes of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling, blood vessel development, and grooming behavior. We expected differences in vascularization between Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw, but we did not anticipate strain-specific differences in blood vessel development, as the two background strains appeared to have similar organization of blood vessels at P1 and P8 using PECAM immunohistochemistry to visualize the vessels (90). Vascularization of the pituitary gland is important for allowing hormones to be secreted and taken to target organs and to allow negative feedback signals to reach the pituitary gland (60). Despite the importance of vascular development for transport of hormones, there is still much to be learned about how this process is regulated in development (41, 76, 83). In particular, we are interested in whether the development of the vasculature stimulates pituitary cell differentiation as it does in the pancreas (52, 53).

Different effects of Prop1 and Pit1 on gonadotropes.

NR5A1 expression is elevated in Prop1df/df and Pit1dw/dw mutants, although the increase is much more profound in Pit1 mutants. The expression of TPIT and POMC are similar in both mutants and wild types. Thus, elevated NR5A1 expression is independent of TPIT expression status in these cases. Thus, different mechanisms must underlie the elevation of Nr5a1 transcription in the Prop1 and Pit1 mutants relative to Tpit mutants. It is intriguing that LHβ expression is diminished in Prop1df/df and expanded in Pit1dw/dw, even though NR5A1 is expanded in both mutants. We hypothesize that Prop1 plays a distinct role in the differentiation and function of gonadotropes, independent of gonadotrope-specific transcription factors such as Nr5a1 and Gata2. Transgenic mice that over-express Prop1 exhibit delayed gonadotrope differentiation, but there is no decrease in the known gonadotrope transcription regulators, Nr0b1, Nr5a1, Gata2, or Egr1 (20, 88). Furthermore, human PROP1 patients exhibit decreased gonadotropin production, while PIT1 deficient patients do not have this feature (68). The precise role of Prop1 in gonadotrope development is not clear.

Novel genes and pathways uncovered by expression analysis.

Our analysis of genes with similar expression changes in both strains of dwarf mutants relative to wild type revealed several novel genes not previously analyzed in either Prop1df/df or Pit1dw/dw mutants (Table 1). A few of these, such as Pappa2, Rxrg, and Gnmt, play known roles in transcription factor activity and endocrinology (18, 58, 81). Pappalysin 2 (Pappa2) exhibits an enzymatic activity by cleaving insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP-5) in addition to being involved in normal postnatal growth (18). Retinoid X receptor gamma (Rxrg) regulates transcription by acting as a homodimer or heterodimer with a number of nuclear and orphan receptors (58). Rxrg is expressed in the thyrotrope cells in the pituitary gland (81). Glycine N-methylase (Gnmt) is directly regulated by growth hormone (1). Although these genes are unlikely to be direct targets of the Pit1 and Prop1 genes, they may be relevant participants in the adult phenotypes of both dwarf mutants.

Several biological processes that were expected to be different between the Prop1 and Pit1 dwarf mice based on their phenotypic variance were, in fact, altered in the microarray analysis of expression (Table 2). Due to the dysmorphology characteristic of the newborn Prop1df/df, we anticipated finding genes involved in tissue remodeling, organ morphogenesis, and anterior/posterior pattern formation. Some more noteworthy biological process GO terms were hormone metabolism, gland development, tissue development, and frizzled signaling pathway. Hormone metabolism included Sult1e1 (sulfotransferase family 1E, member 1). Posttranslational modification by sulfonation of apsaragine-linked oligosaccharides is shown to influence the bioactivity of LH by regulating its half-life in circulation (7). Sulfonated LH is more rapidly removed from the plasma, and this is necessary for the characteristic episodic rise and fall in levels of plasma LH that is essential for maximal bioactivity (6). The Prop1df/df mutant has relatively normal LHβ immunoreactivity in the pituitary gland, but it has low levels of circulating LH. The overexpression of Sult1e1 might cause excessive sulfonation of LHβ, leading to rapid breakdown in the bloodstream.

Nine genes are differentially expressed in the Prop1df/df vs. Pit1dw/dw, as well as in Prop1df/df vs. wild type, and were confirmed by RT-qPCR. These genes constitute an explicit list of possible Prop1-specific genes. The elevated expression of Adamdec1 (ADAM-like, decysin 1) and Cldn10 (Claudin 10) are of particular interest because of their potential roles in cell adhesion, which appears to be excessive and/or abnormally persistent in Prop1 mutants. Adamdec1 is significantly increased in the Prop1df/df pituitary gland. It is likely to be secreted and is a member of the Adam family of trans-membrane genes that have cell adhesion and protease activities (62). Claudin proteins are important components of tight junctions (87). Tight junctions act as a barrier so that molecules do not pass between two interacting cells (2). An inability of cells to receive molecular signals that cue migration and/or differentiation may account for the dysmorphic pituitary seen in the Prop1 mutants. It has recently been shown that the Prop1 mutant mouse pituitary has an expanded expression pattern of N-cadherin (42), a cell adhesion molecule that must be down regulated for cell motility. Moreover, different pituitary cell types exhibit unique cadherin expression profiles, which could affect cell adhesion and consequently cell sorting and networks in the pituitary gland (15). One can hypothesize that claudins, also cell adhesion molecules, may play a similar role in the organogenesis of the developing pituitary gland.

Differential notch signaling in Prop1 mutants.

Various members of the Notch signaling pathway have been implicated in pituitary gland development (50, 71, 72, 97). In particular, expression of Hey1, a transcriptional repressor and potential downstream target of Notch2, is reduced in transgenic mice with constitutively activated Notch signaling (74). Consistent with this, we observed elevated expression of Hey1 in Prop1 mutants, which fail to activate Notch2 expression. Hey1 is normally expressed in the developing pituitary gland from e11.5 to e14.5 and then becomes greatly reduced at e16.5 (74). Hey1 promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and organization of vessel formation (34). HEY1 inhibits bHLH function, which can impact establishment of cell lineages (85). In particular, bHLH protein upstream stimulatory factor 1 (USF1) reduces the activity of α-subunit promoters (Cga) in pituitary cells (45, 46). Furthermore, misexpression of Hey genes during development, and their ability to repress helix-loop-helix genes, affects cell fate in neurons by maintaining neural precursor cells that are meant to differentiate into late-born cell types (75). It is possible that the role of Hey1 in the pituitary gland is similar, namely transforming progenitor gonadotropes into hormone producing gonadotropes.

Loss of Prop1 causes persistent Otx2 expression.

The expression pattern of the transcriptional repressor OTX2 during pituitary development has important implications for understanding the role of OTX2 deficiency on hypopituitarism. Otx2 expression in the neural ectoderm suggests that it could affect FGF- and/or BMP-mediated induction of Rathke's pouch (26). Otx2 expression in the pouch itself suggests the possibility of an intrinsic role in pouch development as well. Otx2 is able to activate Hesx1 expression (28), and Hesx1 is necessary for normal pituitary development and function (22, 25). The expression pattern of Otx2 is consistent with the proposed role of regulating Hesx1 expression. In contrast, the idea that Otx2 regulates Pit1 expression (24) seems unlikely based on the lack of expression of Otx2 in the caudo-medial area of the gland of wild-type mice where Pit1 is normally activated at e14.5 (4, 36). The relative contributions of normal Otx2 expression in the ventral diencephalon and Rathke's pouch for induction and maintenance of Hesx1 expression could be assessed with tissue-specific disruptions of the Otx2 expression (35).

The normal expression patterns of Prop1 and Otx2 are not consistent with Prop1 directly repressing Otx2 expression. Aberrant Otx2 transcripts are not detected in Prop1 mutants until e16.5, 4 days after Prop1 expression peaks and 2 days after obvious dysmorphology is evident in Prop1 mutants. Prop1 may be required for activating expression of a gene or genes that suppress Otx2 in the anterior and intermediate lobes, or Prop1 could suppress an activator of Otx2 that is expressed in pouch derivatives. The consequences of ectopic expression of Otx2 in the pituitary of Prop1 mutants are not clear, but it could contribute to the unique defects in Prop1 mutant pituitary glands.

Pathway analysis identifies genes associated with Otx2.

A hypothetical pathway generated by Bibliosphere software indicates a number of potential downstream targets for Otx2 that could contribute to the Prop1 mutant phenotype. A decrease in Otx2 results in a decrease in Neurod1 expression, which is required for early corticotrope differentiation (54). According to this gene pathway, decreased Neurod1 in the pituitary gland also leads to a decrease in Neurod4 expression, also reported in mouse retina (17). Neurod4 functions in the Notch signaling pathway by maintaining Notch ligand expression (65). It remains unclear whether Neurod4 is involved in the Notch pathway within the development of the pituitary gland, but it appears to be necessary for the proper onset of somatotrope specification (97).

Both Sox2 and Nr2e1 are markers for stem cells, and their expression is increased concomitant with an increase of Otx2 in the Prop1 mutants. The pituitary gland has a population of multipotent progenitor cells that are marked by Sox2 (33). Prop1 mutants might be enriched for this stage of progenitor cells, due to the defects in transitioning from proliferation to differentiation (90). Later stages of progenitors are lacking in Prop1 mutants. Although Nr2e1 expression has not been previously reported in the pituitary gland, it may be important for maintaining the multipotent and proliferative state of stem cells there, as it does in adult brain (77). These findings suggest that Prop1 may play an important role in regulating progenitor or stem cell activity as suggested by the coexpression of Prop1 with the stem-cell marker Sox2 (92).

Conclusion

Here we report a collection of potential downstream factors and pathways regulated by the Prop1 and Pit1 genes. Otx2 expression is elevated of Prop1 mutants, and it plays a significant role in the formation of the gland in mouse and man. Pathway analyses suggest that Otx2 could be involved in the Notch pathway and stem cell perseverance in the developing pituitary gland. The other differentially expressed genes we report could also have important roles in pituitary development and function. Thus, this study lays a foundation for functional studies to define the roles of these novel genes and pathways in pituitary gland molecular processes.

GRANTS

Grants or fellowships: NIH Grants R37HD-30428, R01HD-34283, R01GM-72007; University of Michigan Center for Computational Medicine and Biology (S. A. Camper, D. Ghosh).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Institutes of Heath (NIH) for funding (R01HD-34283, R37HD-30428 to S. A. Camper), the Center for Computational Medicine and Biology for a Pilot Feasibility funding (S. A. Camper and D. Ghosh), and the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center Affymetrix and cDNA Microarray Core Facility (P30CA-46592), especially Joe Washburn and Craig Johnson, for expert assistance. We thank Drs. John Rubenstein, Ken-Ichirou Morohashi, Simon Rhodes, and Jacques Drouin and the National Hormone Pituitary Program for providing us with critical reagents. Finally, we thank Drs. Christopher Krebs, Jun Z. Li, David Langlais, and Jacques Drouin for comments on the manuscript.

Current address for D. Ghosh, Dept. Statistics. Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida K, Tawata M, Negishi M, Onaya T. Mouse glycine N-methyltransferase is sexually dimorphic and regulated by growth hormone. Horm Metab Res 29: 646–649, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts B. Molecular Biology of The Cell. New York: Garland Publishing, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexa A, Rahnenführer J, Lengauer T. Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data be decorrelating go graph structure. Bioinformatics 22: 1600–1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen B, Pearse RV, 2nd, Jenne K, Sornson M, Lin SC, Bartke A, Rosenfeld MG. The Ames dwarf gene is required for Pit-1 gene activation. Dev Biol 172: 495–503, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aujla PK, Bora A, Monahan P, Sweedler JV, Raetzman LT. The Notch effector gene Hes1 regulates migration of hypothalamic neurons, neuropeptide content and axon targeting to the pituitary. Dev Biol 353: 61–71, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baenziger JU. Glycosylation: to what end for the glycoprotein hormones? Endocrinology 137: 1520–1522, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baenziger JU, Kumar S, Brodbeck RM, Smith PL, Beranek MC. Circulatory half-life but not interaction with the lutropin/chorionic gonadotropin receptor is modulated by sulfation of bovine lutropin oligosaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 334–338, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartke A, Goldman BD, Bex F, Dalterio S. Effects of prolactin (PRL) on pituitary and testicular function in mice with hereditary PRL deficiency. Endocrinology 101: 1760–1766, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behan LA, Agha A. Endocrine consequences of adult traumatic brain injury. Horm Res 68, Suppl 5: 18–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B 57: 289–300, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnefont X, Lacampagne A, Sanchez-Hormigo A, Fino E, Creff A, Mathieu MN, Smallwood S, Carmignac D, Fontanaud P, Travo P, Alonso G, Courtois-Coutry N, Pincus SM, Robinson IC, Mollard P. Revealing the large-scale network organization of growth hormone-secreting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16880–16885, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckwalter MS, Katz RW, Camper SA. Localization of the panhypopituitary dwarf mutation (df) on mouse chromosome 11 in an intersubspecific backcross. Genomics 10: 515–526, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camper SA, Saunders TL, Katz RW, Reeves RH. The Pit-1 transcription factor gene is a candidate for the murine Snell dwarf mutation. Genomics 8: 586–590, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cha KB, Douglas KR, Potok MA, Liang H, Jones SN, Camper SA. WNT5A signaling affects pituitary gland shape. Mech Dev 121: 183–194, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauvet N, El-Yandouzi T, Mathieu MN, Schlernitzauer A, Galibert E, Lafont C, Le Tissier P, Robinson IC, Mollard P, Coutry N. Characterization of adherens junction protein expression and localization in pituitary cell networks. J Endocrinol 202: 375–387, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng TC, Beamer WG, Phillips JA, 3rd, Bartke A, Mallonee RL, Dowling C. Etiology of growth hormone deficiency in little, Ames, and Snell dwarf mice. Endocrinology 113: 1669–1678, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho JH, Klein WH, Tsai MJ. Compensational regulation of bHLH transcription factors in the postnatal development of BETA2/NeuroD1-null retina. Mech Dev 124: 543–550, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christians JK, Hoeflich A, Keightley PD. PAPPA2, an enzyme that cleaves an insulin-like growth-factor-binding protein, is a candidate gene for a quantitative trait locus affecting body size in mice. Genetics 173: 1547–1553, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cushman LJ, Watkins-Chow DE, Brinkmeier ML, Raetzman LT, Radak AL, Lloyd RV, Camper SA. Persistent Prop1 expression delays gonadotrope differentiation and enhances pituitary tumor susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet 10: 1141–1153, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, Kostov G, Athey B, Jones EG, Bunney WE, Myers RM, Speed TP, Akil H, Watson SJ, Meng F. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucl Acids Res 33: e175, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dasen JS, Barbera JP, Herman TS, Connell SO, Olson L, Ju B, Tollkuhn J, Baek SH, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. Temporal regulation of a paired-like homeodomain repressor/TLE corepressor complex and a related activator is required for pituitary organogenesis. Genes Dev 15: 3193–3207, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasen JS, O'Connell SM, Flynn SE, Treier M, Gleiberman AS, Szeto DP, Hooshmand F, Aggarwal AK, Rosenfeld MG. Reciprocal interactions of Pit1 and GATA2 mediate signaling gradient-induced determination of pituitary cell types. Cell 97: 587–598, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dateki S, Fukami M, Sato N, Muroya K, Adachi M, Ogata T. OTX2 mutation in a patient with anophthalmia, short stature, and partial GH deficiency: functional studies using the IRBP, HESX1, and POU1F1 promoters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 3697–3702, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dattani MT, Martinez-Barbera JP, Thomas PQ, Brickman JM, Gupta R, Martensson IL, Toresson H, Fox M, Wales JK, Hindmarsh PC, Krauss S, Beddington RS, Robinson IC. Mutations in the homeobox gene HESX1/Hesx1 associated with septo-optic dysplasia in human and mouse. Nat Genet 19: 125–133, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis SW, Camper SA. Noggin regulates Bmp4 activity during pituitary induction. Dev Biol 305: 145–160, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis SW, Castinetti F, Carvalho LR, Ellsworth BS, Potok MA, Lyons RH, Brinkmeier ML, Raetzman LT, Carninci P, Mortensen AH, Hayashizaki Y, Arnhold IJ, Mendonca BB, Brue T, Camper SA. Molecular mechanisms of pituitary organogenesis: In search of novel regulatory genes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 323: 4–19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaczok D, Romero C, Zunich J, Marshall I, Radovick S. A novel dominant negative mutation of OTX2 associated with combined pituitary hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 4351–4359, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorn C, Ou Q, Svaren J, Crawford PA, Sadovsky Y. Activation of luteinizing hormone beta gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires the synergy of early growth response-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem 274: 13870–13876, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglas KR, Brinkmeier ML, Kennell JA, Eswara P, Harrison TA, Patrianakos AI, Sprecher BS, Potok MA, Lyons RH, Jr, MacDougald OA, Camper SA. Identification of members of the Wnt signaling pathway in the embryonic pituitary gland. Mamm Genome 12: 843–851, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ericson J, Norlin S, Jessell TM, Edlund T. Integrated FGF and BMP signaling controls the progression of progenitor cell differentiation and the emergence of pattern in the embryonic anterior pituitary. Development 125: 1005–1015, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fauquier T, Rizzoti K, Dattani M, Lovell-Badge R, Robinson IC. SOX2-expressing progenitor cells generate all of the major cell types in the adult mouse pituitary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2907–2912, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer A, Schumacher N, Maier M, Sendtner M, Gessler M. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev 18: 901–911, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fossat N, Courtois V, Chatelain G, Brun G, Lamonerie T. Alternative usage of Otx2 promoters during mouse development. Dev Dyn 233: 154–160, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gage PJ, Brinkmeier ML, Scarlett LM, Knapp LT, Camper SA, Mahon KA. The Ames dwarf gene, df, is required early in pituitary ontogeny for the extinction of Rpx transcription and initiation of lineage-specific cell proliferation. Mol Endocrinol 10: 1570–1581, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gage PJ, Roller ML, Saunders TL, Scarlett LM, Camper SA. Anterior pituitary cells defective in the cell-autonomous factor, df, undergo cell lineage specification but not expansion. Development 122: 151–160, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giordano BC, Ferrance J, Swedberg S, Huhmer AF, Landers JP. Polymerase chain reaction in polymeric microchips: DNA amplification in less than 240 seconds. Anal Biochem 291: 124–132, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green EL. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. New York: Dover Publications, 1968, p. 197 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halvorson LM, Ito M, Jameson JL, Chin WW. Steroidogenic factor-1 and early growth response protein 1 act through two composite DNA binding sites to regulate luteinizing hormone beta-subunit gene expression. J Biol Chem 273: 14712–14720, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto H, Ishikawa H, Kusakabe M. Three-dimensional analysis of the developing pituitary gland in the mouse. Dev Dyn 212: 157–166, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Himes AD, Raetzman LT. Premature differentiation and aberrant movement of pituitary cells lacking both Hes1 and Prop1. Dev Biol 325: 151–161, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingraham HA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Shen WH, Nachtigal MW, Abbud R, Nilson JH, Parker KL. The nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 acts at multiple levels of the reproductive axis. Genes Dev 8: 2302–2312, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucl Acids Res 31: e15, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson SM, Barnhart KM, Mellon PL, Gutierrez-Hartmann A, Hoeffler JP. Helix-loop-helix proteins are present and differentially expressed in different cell lines from the anterior pituitary. Mol Cell Endocrinol 96: 167–176, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson SM, Gutierrez-Hartmann A, Hoeffler JP. Upstream stimulatory factor, a basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein, regulates the activity of the alpha-glycoprotein hormone subunit gene in pituitary cells. Mol Endocrinol 9: 278–291, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelberman D, Rizzoti K, Lovell-Badge R, Robinson IC, Dattani MT. Genetic regulation of pituitary gland development in human and mouse. Endocrine Rev 30: 790–829, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keri RA, Nilson JH. A steroidogenic factor-1 binding site is required for activity of the luteinizing hormone beta subunit promoter in gonadotropes of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 271: 10782–10785, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kioussi C, Briata P, Baek SH, Rose DW, Hamblet NS, Herman T, Ohgi KA, Lin C, Gleiberman A, Wang J, Brault V, Ruiz-Lozano P, Nguyen HD, Kemler R, Glass CK, Wynshaw-Boris A, Rosenfeld MG. Identification of a Wnt/Dvl/beta-Catenin –> Pitx2 pathway mediating cell-type-specific proliferation during development. Cell 111: 673–685, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kita A, Imayoshi I, Hojo M, Kitagawa M, Kokubu H, Ohsawa R, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R, Hashimoto N. Hes1 and Hes5 control the progenitor pool, intermediate lobe specification, and posterior lobe formation in the pituitary development. Mol Endocrinol 21: 1458–1466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lalli E, Melner MH, Stocco DM, Sassone-Corsi P. DAX-1 blocks steroid production at multiple levels. Endocrinology 139: 4237–4243, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lammert E, Cleaver O, Melton D. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science 294: 564–567, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lammert E, Cleaver O, Melton D. Role of endothelial cells in early pancreas and liver development. Mech Dev 120: 59–64, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lamolet B, Poulin G, Chu K, Guillemot F, Tsai MJ, Drouin J. Tpit-independent function of NeuroD1(BETA2) in pituitary corticotroph differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 18: 995–1003, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lamolet B, Pulichino AM, Lamonerie T, Gauthier Y, Brue T, Enjalbert A, Drouin J. A pituitary cell-restricted T box factor, Tpit, activates POMC transcription in cooperation with Pitx homeoproteins. Cell 104: 849–859, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Rawson EJ, Simmons DM, Swanson LW, Rosenfeld MG. Dwarf locus mutants lacking three pituitary cell types result from mutations in the POU-domain gene pit-1. Nature 347: 528–533, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-Delta Delta C(T)] method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell 83: 841–850, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsuo I, Kuratani S, Kimura C, Takeda N, Aizawa S. Mouse Otx2 functions in the formation and patterning of rostral head. Genes Dev 9: 2646–2658, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Melmed S. The Pituitary. Los Angeles: Blackwell Science, Ind., 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Melo ME, Marui S, Carvalho LR, Arnhold IJ, Leite CC, Mendonca BB, Knoepfelmacher M. Hormonal, pituitary magnetic resonance, LHX4 and HESX1 evaluation in patients with hypopituitarism and ectopic posterior pituitary lobe. Clin Endocrinol 66: 95–102, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mueller CG, Cremer I, Paulet PE, Niida S, Maeda N, Lebeque S, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C. Mannose receptor ligand-positive cells express the metalloprotease decysin in the B cell follicle. J Immunol 167: 5052–5060, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murakami T, Kikuta A, Taguchi T, Ohtsuka A, Ohtani O. Blood vascular architecture of the rat cerebral hypophysis and hypothalamus. A dissection/scanning electron microscopy of vascular casts. Arch Histol Jpn 50: 133–176, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nasonkin IO, Ward RD, Raetzman LT, Seasholtz AF, Saunders TL, Gillespie PJ, Camper SA. Pituitary hypoplasia and respiratory distress syndrome in Prop1 knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet 13: 2727–2735, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohsawa R, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R. Mash1 and Math3 are required for development of branchiomotor neurons and maintenance of neural progenitors. J Neurosci 25: 5857–5865, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olson LE, Tollkuhn J, Scafoglio C, Krones A, Zhang J, Ohgi KA, Wu W, Taketo MM, Kemler R, Grosschedl R, Rose D, Li X, Rosenfeld MG. Homeodomain-mediated beta-catenin-dependent switching events dictate cell-lineage determination. Cell 125: 593–605, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park SY, Meeks JJ, Raverot G, Pfaff LE, Weiss J, Hammer GD, Jameson JL. Nuclear receptors Sf1 and Dax1 function cooperatively to mediate somatic cell differentiation during testis development. Development 132: 2415–2423, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfaffle RW, Blankenstein O, Wuller S, Kentrup H. Combined pituitary hormone deficiency: role of Pit-1 and Prop-1. Acta Paediatr Suppl 88: 33–41, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Potok MA, Cha KB, Hunt A, Brinkmeier ML, Leitges M, Kispert A, Camper SA. WNT signaling affects gene expression in the ventral diencephalon and pituitary gland growth. Dev Dyn 237: 1006–1020, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pulichino AM, Vallette-Kasic S, Tsai JP, Couture C, Gauthier Y, Drouin J. Tpit determines alternate fates during pituitary cell differentiation. Genes Dev 17: 738–747, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raetzman LT, Cai JX, Camper SA. Hes1 is required for pituitary growth and melanotrope specification. Dev Biol 304: 455–466, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raetzman LT, Ross SA, Cook S, Dunwoodie SL, Camper SA, Thomas PQ. Developmental regulation of Notch signaling genes in the embryonic pituitary: Prop1 deficiency affects Notch2 expression. Dev Biol 265: 329–340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raetzman LT, Ward R, Camper SA. Lhx4 and Prop1 are required for cell survival and expansion of the pituitary primordia. Development 129: 4229–4239, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raetzman LT, Wheeler BS, Ross SA, Thomas PQ, Camper SA. Persistent expression of Notch2 delays gonadotrope differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 20: 2898–2908, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sakamoto M, Hirata H, Ohtsuka T, Bessho Y, Kageyama R. The basic helix-loop-helix genes Hesr1/Hey1 and Hesr2/Hey2 regulate maintenance of neural precursor cells in the brain. J Biol Chem 278: 44808–44815, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sasaki F, Iwama Y. Correlation of spatial differences in concentrations of prolactin and growth hormone cells with vascular pattern in the female mouse adenohypophysis. Endocrinology 122: 1622–1630, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi Y, Chichung Lie D, Taupin P, Nakashima K, Ray J, Yu RT, Gage FH, Evans RM. Expression and function of orphan nuclear receptor TLX in adult neural stem cells. Nature 427: 78–83, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simeone A, Acampora D, Mallamaci A, Stornaiuolo A, D'Apice MR, Nigro V, Boncinelli E. A vertebrate gene related to orthodenticle contains a homeodomain of the bicoid class and demarcates anterior neuroectoderm in the gastrulating mouse embryo. EMBO J 12: 2735–2747, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3: Article 3, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sornson MW, Wu W, Dasen JS, Flynn SE, Norman DJ, O'Connell SM, Gukovsky I, Carriere C, Ryan AK, Miller AP, Zuo L, Gleiberman AS, Andersen B, Beamer WG, Rosenfeld MG. Pituitary lineage determination by the Prophet of Pit-1 homeodomain factor defective in Ames dwarfism. Nature 384: 327–333, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sugawara A, Yen PM, Qi Y, Lechan RM, Chin WW. Isoform-specific retinoid-X receptor (RXR) antibodies detect differential expression of RXR proteins in the pituitary gland. Endocrinology 136: 1766–1774, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suh H, Gage PJ, Drouin J, Camper SA. Pitx2 is required at multiple stages of pituitary organogenesis: pituitary primordium formation and cell specification. Development 129: 329–337, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Szabo K. Origin of the adenohypophyseal vessels in the rat. J Anat 154: 229–235, 1987 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tang K, Bartke A, Gardiner CS, Wagner TE, Yun JS. Gonadotropin secretion, synthesis, and gene expression in human growth hormone transgenic mice and in Ames dwarf mice. Endocrinology 132: 2518–2524, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tapscott SJ, Weintraub H. MyoD and the regulation of myogenesis by helix-loop-helix proteins. J Clin Invest 87: 1133–1138, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Treier M, Gleiberman AS, O'Connell SM, Szeto DP, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Rosenfeld MG. Multistep signaling requirements for pituitary organogenesis in vivo. Genes Dev 12: 1691–1704, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev 2: 285–293, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vesper AH, Raetzman LT, Camper SA. Role of prophet of Pit1 (PROP1) in gonadotrope differentiation and puberty. Endocrinology 147: 1654–1663, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ward RD, Raetzman LT, Suh H, Stone BM, Nasonkin IO, Camper SA. Role of PROP1 in pituitary gland growth. Mol Endocrinol 19: 698–710, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ward RD, Stone BM, Raetzman LT, Camper SA. Cell proliferation and vascularization in mouse models of pituitary hormone deficiency. Mol Endocrinol 20: 1378–1390, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watkins-Chow DE, Douglas KR, Buckwalter MS, Probst FJ, Camper SA. Construction of a 3-Mb contig and partial transcript map of the central region of mouse chromosome 11. Genomics 45: 147–157, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshida S, Kato T, Susa T, Cai LY, Nakayama M, Kato Y. PROP1 coexists with SOX2 and induces PIT1-commitment cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385: 11–15, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yuen T, Wurmbach E, Pfeffer RL, Ebersole BJ, Sealfon SC. Accuracy and calibration of commercial oligonucleotide and custom cDNA microarrays. Nucl Acids Res 30: e48, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zazopoulos E, Lalli E, Stocco DM, Sassone-Corsi P. DNA binding and transcriptional repression by DAX-1 blocks steroidogenesis. Nature 390: 311–315, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhao D, Yang J, Jones KE, Gerald C, Suzuki Y, Hogan PG, Chin WW, Tashjian AH., Jr Molecular cloning of a complementary deoxyribonucleic acid encoding the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor and regulation of its messenger ribonucleic acid in rat GH cells. Endocrinology 130: 3529–3536, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu X, Zhang J, Tollkuhn J, Ohsawa R, Bresnick EH, Guillemot F, Kageyama R, Rosenfeld MG. Sustained Notch signaling in progenitors is required for sequential emergence of distinct cell lineages during organogenesis. Genes Dev 20: 2739–2753, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]