Abstract

To characterize the endothelial dysfunction associated with Type II diabetes, we surveyed transcriptional responses in the vascular endothelia of mice receiving a diabetogenic, high-fat diet. Tie2-GFP mice were fed a diet containing 60% fat calories (HFD); controls were littermates fed normal chow. Following 4, 6, and 8 wk, aortic and leg muscle tissues were enzymatically dispersed, and endothelial cells were obtained by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Relative mRNA abundance in HFD vs. control endothelia was measured with long-oligo microarrays; highly dysregulated genes were confirmed by real-time PCR and protein quantification. HFD mice were hyperglycemic by 2 wk and displayed vascular insulin resistance and decreased glucose tolerance by 5 and 6 wk, respectively. Endothelial transcripts upregulated by HFD included galectin-3 (Lgals3), 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein, and chemokine ligands 8 and 9. Increased LGALS3 protein was detected in muscle endothelium by immunohistology accompanied by elevated LGALS3 in the serum of HFD mice. Our comprehensive analysis of the endothelial transcriptional response in a model of Type II diabetes reveals novel regulation of transcripts with roles in inflammation, insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress, and atherosclerosis. Increased endothelial expression and elevated humoral levels of LGALS3 supports a role for this molecule in the vascular response to diabetes, and its potential as a direct biomarker for the inflammatory state in diabetes.

Keywords: gene expression, microarray, vascular biology, endothelial dysfunction, metabolic syndrome

type ii diabetes is associated with increased atherosclerosis, retinopathy, skin ulceration, and other vascular-related diseases, all of which may involve damaged or dysfunctional endothelium. A major consequence of diabetes is endothelial exposure to elevated glucose and fatty acids, leading to endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and subsequent generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (46) as well as the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) (45). Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia and other hormonal changes can alter endothelial signaling pathways (34). These changes may promote inflammation, impair vasoregulation, disrupt hemostasis, and inhibit reverse cholesterol transport (2, 32). By examining the transcriptional changes that occur in both the micro- and macrovascular endothelium of mice exposed to a dietary model of Type II diabetes, we expect to gain further insight into the underlying mechanisms of the endothelial dysfunction characteristic of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome.

Transcriptional analysis has been used to examine the responses of cultured endothelium exposed to high glucose and insulin (9, 44). However, an in vitro analysis may only partially reflect the complex in vivo state, where numerous hormonal, metabolic, and cellular perturbations combine to influence the endothelial cell. In vivo analysis of aortic endothelium from mice exposed to a Type I, insulin-deficient, model of diabetes revealed dysregulation of transcripts involved in inflammation and insulin sensitivity (24). Here, we study mice rendered diabetic by a high-fat diet (HFD) and comprehensively evaluate arterial as well as capillary endothelial transcriptional responses in a model of Type II, insulin resistant, diabetes. For this purpose, we utilize transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the endothelial-specific Tie2 promotor (Tie2-GFP). By selecting our endothelial cell population based on GFP expression as well as CD31 surface staining, we achieve a high degree of purity of the analyzed cells, assuring that our results represent transcriptional changes specifically in the diabetic endothelium.

METHODS

Animals and diet.

Mice homozygous for the Tie2-GFP transgene [Tg(TIE2GFP)287Sato, stock no. 003658; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME] were bred for these experiments. Beginning at 8 wk of age, male mice were allowed to feed ad libitum on an HFD containing 60% fat calories (BioServ cat. no. S3282) for a period of 4, 6, or 8 wk. Littermates fed a normal chow diet containing 12% fat calories (LabDiet cat. no. 5001) served as controls. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Hawaii.

Fasting glucose levels and glucose tolerance test.

Before the start of the respective diet regimens and after 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 wk of feeding, glucose levels were determined by glucometry of the tail blood following an overnight fast (OneTouch Ultra; LifeScan). A glucose tolerance test was performed after 6 wk on the diet regimen. Glucose (1 mg/g body wt ip) was administered following an overnight fast. Glucometry of the tail blood was performed prior to glucose injection and every 20 min afterwards for 2 h. The area under the curve was determined using the statistical software in Graphpad.

Determination of serum galectin-3 and insulin levels.

We collected 200 μl of blood from the tail vein, allowed it to clot, and centrifuged it at 5,000 rpm for 10 min to separate serum. Quantification of galectin-3 in the serum of mice after 4, 6, and 8 wk on the diet following an overnight fast was performed using the Mouse Galectin-3 Duoset ELISA Development Kit (R&D Systems cat. no. DY1197).

Following an overnight fast, serum insulin levels were measured at 3, 6, and 8 wk with a Mercodia Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (cat. no. 10-1149-01). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the fasting glucose and insulin concentrations at 3, 6, and 8 wk on the diet using the following formula: [fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) × fasting insulin (μIU/ml)] / 405 (1), where 1 mg insulin = 26 IU (0.038 mg/IU) as defined by the 1st International Standard for insulin published by the World Health Organization in 1986.

Measurement of vascular insulin resistance.

Following 5 wk on the diet, six control and six high fat-fed mice received an injection of insulin (0.06 U/g body wt in 300 μl of sterile saline ip); two or three animals of each group received vehicle (normal saline). Mice were killed 15 min after injection. The thoracic aorta was excised, dissected from adherent fat, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein was subsequently extracted from the tissue and phospho-AKT (serine 473) levels were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, cat. no. DYC887-2) and normalized to total protein concentration.

Endothelial cell isolation.

Following 4, 6, or 8 wk on the diet regimen, animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. HFD-fed animals and chow-fed controls were processed on the same day. In each experiment, pooled cells from three experimental and three control mice were collected for each tissue. Aortae from the aortic root to the iliac bifurcation were dissected. Leg muscles consisting of the plantaris, gastronemius, and biceps femoris (which are readily dissected as a single group) were excised. Tissues were placed into ice-cold PBS and freed of adherent fat. The aortic and skeletal muscle tissues from three animals were each pooled, minced into 1 mm fragments, and dispersed as previously described (24, 25). Suspensions of collagenolytically separated cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (1:500) for 5 min and then with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse CD31 (1:200) for 25 min on ice (eBiosciences cat. nos. 14-0161 and 12-0311). We isolated 10,000 endothelial cells positive for both GFP and phycoerythrin staining on a FACSAria (Becton Dickinson) directly into TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA was purified with RNeasy columns (Qiagen) to yield <80 ng, which was then amplified using an Amino Allyl MessageAmp kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol to produce ∼100 μg of amino-allyl modified cRNA.

Microarray analysis.

Microarray analyses were performed to determine the transcriptional responses in aortic and skeletal muscle endothelium from mice exposed to HFD vs. control diet for 4, 6, and 8 wk. Amino-allyl modified cRNA was labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 CyDye Post-Labeling Reactive Dye Pack (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following purification, 200 pmoles of Cy3 and Cy5 dye-labeled cRNA, as measured by NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), were combined and fragmented with Ambion 10X fragmentation reagents at 70°C for 15 min. Yeast tRNA (4 μg), polyA RNA (4 μg), mouse cot-1 DNA (1 μg), and Slidehyb III hybridization buffer (Ambion) were added for a total sample volume of 35 μl. In general, biological replicate experiments were performed for each time point for both tissues. For each of the two biological replicate experiments, two array hybridizations were performed, each of which included a dye reversal. Samples were hybridized overnight to glass slides spotted with the Operon Murine V4 oligo set produced by the Duke University Microarray Core. Arrays were scanned using a Genepix 4000B (Molecular Devices) system and analyzed with Genepix and Acuity software.

Statistical analysis of microarray results was performed using the functions available within Acuity. Results were normalized using the ratio of medians method and filtered to exclude any exhibiting the following characteristics: a percentage of saturated pixels >3, a signal/noise ratio <3, a (regression ratio 635/532)2 <0.6, or a Genepix flag. Transcripts exhibiting upregulation [a log2(fold-change) >0.7] or downregulation [log2(fold-change) <−0.7] that were found consistently dysregulated at 4, 6, and 8 wk were tabulated for each tissue. (A log2 fold-change of 0.7 corresponds to 1.6-fold on the linear scale). The one sample t-test function within Acuity was then applied to the results to calculate P values for each experiment (nbiological = 2, nmicroarray = 4).

Real-time PCR.

Microarray results were confirmed by semiquantitative real-time (RT)-PCR performed on three or four biological replicate experiments. Complementary DNA was synthesized by the reverse transcription of 1 μg of amplified RNA from the sorted endothelial cells using qScript (Quanta Biosciences). Oligonucleotide primers were designed to generate amplicons of length 100–200 nucleotides and to span at least one intron. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1.1 cDNA representing 5 ng of total RNA was amplified by PCR performed using SYBR green fluorophore (Roche) in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time PCR system. A standard two-phase reaction (95°C 15 s, 60°C 1 min) worked for all amplifications. Dissociation curves run for each reaction verified the presence of a single amplicon peak, and a single, amplified product of the expected size was confirmed by gel electrophoresis. Amplicons were also sequenced by 3730XL DNA Analyzer (ABI), and BLAST was used to verify the alignment of the amplicon sequence with that of the target transcript (Supplemental Table S1).

The expression level for each gene was interpolated from a standard curve of serial dilutions at cycle times where CT, the threshold intensity, was exceeded. The abundance of Cyclophilin A was assessed in parallel as a loading control to which the genes of interest were normalized. Fold-changes represent the ratio of diabetic to control expression values. Statistical analyses were performed using the one sample t-test function in Analyse-It software for Microsoft Excel.

Immunofluorescence.

GFP+, CD31+ endothelial cells from the leg muscles of three mice receiving HFD and three control diet for 8 wk were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and sorted into tissue culture medium. Aliquots containing 1,000 cells were deposited onto lysine-coated slides by centrifugation at 450 rpm for 5 min with a Shandon Cytospin (Thermo Scientific). Slides were fixed overnight in 10% formalin, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X100 and incubated with rat anti-galectin-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-23938) at 1:100 followed by Alexa fluor-568 goat anti-rat (Invitrogen) at 1:800. Images were collected under controlled exposure and gain settings with an Axiophot system (Zeiss).

RESULTS

Effect of HFD on metabolic parameters.

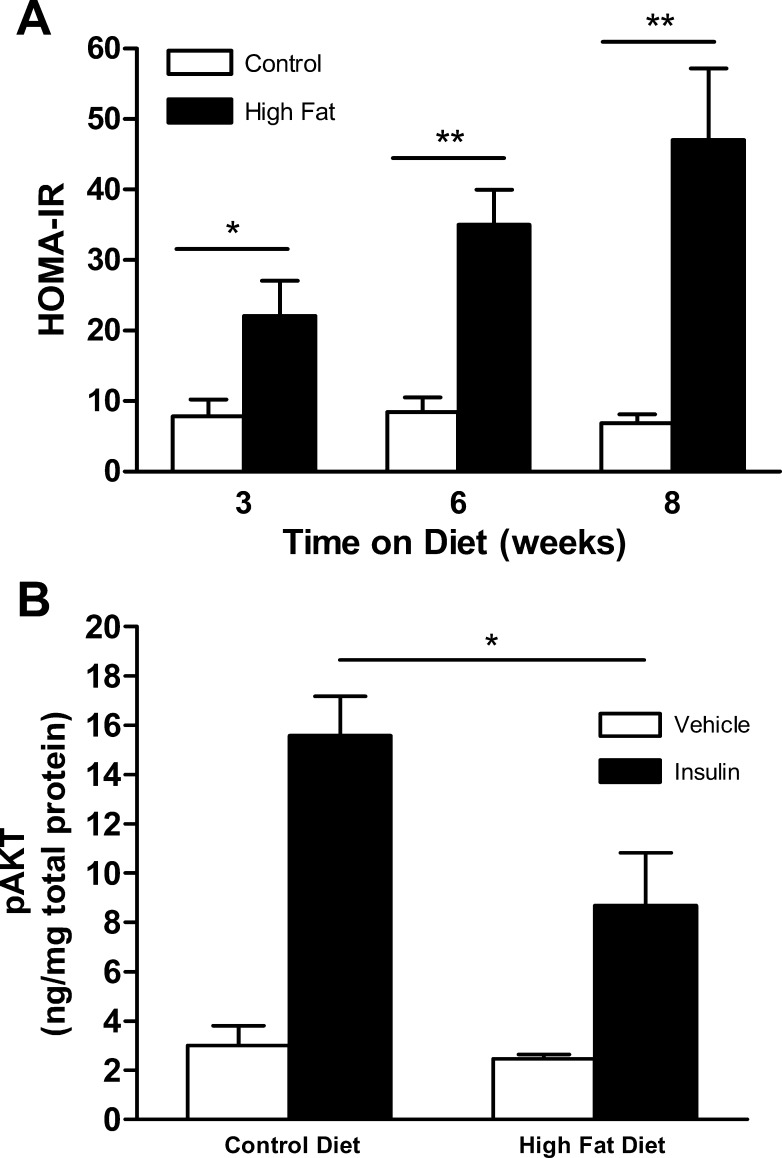

As shown in Table 1, controlled exposure of Tie2-GFP mice to HFD resulted in the expected metabolic changes associated with diabetes, including accelerated weight gain as well as hyperglycemia by 2 wk. These responses were accompanied by marked hyperinsulinemia by 3 wk (Table 1) and an increased HOMA-IR index by 3 wk (Fig. 1A). In addition, exposure to HFD for 5 wk resulted in a reduced vascular response to insulin as reflected in attenuation of aortic AKT phosphorylation following an in vivo insulin challenge (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, glucose tolerance was impaired in mice exposed to a HFD vs. control diet (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Metabolic characteristics of Tie2-GFP mice receiving high-fat diet (60% fat calories) versus chow diet (12%)

| Weeks on Diet | Chow | High Fat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, g | 0 | 22.2 ± 0.9 | 23.8 ± 0.7 |

| 2 | 24.1 ± 0.8 | 30.0 ± 1.6† | |

| 4 | 26.8 ± 0.8 | 31.1 ± 1.3† | |

| 6 | 26.3 ± 0.8 | 33.8 ± 1.2‡ | |

| 8 | 28.0 ± 0.9 | 36.5 ± 1.0‡ | |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 0 | 130 ± 20 | 120 ± 7 |

| 2 | 148 ± 9 | 190 ± 10* | |

| 4 | 116 ± 8 | 163 ± 9‡ | |

| 6 | 139 ± 9 | 210 ± 10‡ | |

| 8 | 111 ± 4 | 182 ± 4‡ | |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| 6 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.4† | |

| 8 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.7† |

Data are means ± SE. Weight measurements and glucometry of the tail blood was performed before the start of the high-fat or chow diet regimen and after 2, 4, 6, and 8 wk of feeding (n = 6–18). Serum insulin levels were quantified by ELISA following 3, 6, and 8 wk on the diet (n = 5-9).

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 vs. chow-fed controls.

Fig. 1.

Endocrine responses of Tie2-GFP mice on high-fat diet (HFD). A: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) calculated from measured glucose and insulin levels after 3, 6, or 8 wk exposure to HFD vs. control diet (n = 5–9). B: aortic AKT phosphorylation (pAKT) in response to insulin administration (0.06 U/g) vs. vehicle (ip) in Tie2-GFP mice after 5 wk exposure to HFD vs. control diet (n = 3–6). Data shown are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Endothelial cell isolation.

FACS yielded at least 10,000 GFP+CD31+ cells from each pooled tissue sample. All GFP+ cells also exhibited phycoerythrin staining (Supplemental Fig. S2A). GFP+CD31+ cell populations represented ∼2.5 and 1.5% of the total population of cells derived from muscle and aortic tissue, respectively. The ability of the sorted cells to take up fluorescent labeled acetylated-LDL (Dil-AcLDL, Biomedical Technologies) and form tubes on Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Biosciences) further confirmed their endothelial identity (Supplemental Fig. S2B) (20, 40).

Tie2-expressing myeloid cells have been reported to account for 2–7% of human blood mononuclear cells (39). Our analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by flow cytometry has shown the percentage of CD11b+GFP+ myeloid cells after 8 wk of HFD to be 0.5 ± 0.5% vs. 0.3 ± 0.4% in controls (n = 3). Furthermore, analysis of the specific inflammatory monocyte population described to express Tie2 revealed that only 0.8% of this CD11b+CD115+ population express Tie2 in blood cell suspensions derived from both HFD- and control-fed animals (0.8 ± 0.5% vs. 0.8 ± 0.3%, n = 3). Most importantly, FACS of muscle tissue suspensions from three independent experiments following 8 wk of diet revealed that only 0.8 ± 0.4% of GFP+ cells derived from HFD animals also displayed the monocyte marker CD11b with similar low percentages observed in control animals (0.3 ± 0.5%).

Microarray results.

Microarray hybridization data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under series record GSE14898. Tables 2 (aortic) and 3 (muscle) display fold-change of transcripts with |log2(fold-change) |>0.7 at all time points in aorta or by 6 or 8 wk of feeding in the muscle in biologically replicate, dye-reversed hybridization experiments. Dysregulated transcripts common to both aortic and muscle endothelium are presented in Table 4.

Table 2.

Average log2 fold-change determined by microarray analysis of dysregulated transcripts in aortic endothelium following 4, 6, and 8 wk of high-fat diet

| RefSeq | Name | 4 wk | 6 wk | 8 wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_010705 | lectin, galactose binding, soluble 3 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| NM_010188 | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity III (Fcgr3) | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| NM_011338 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| NM_021443 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| NM_007572 | complement component 1, q subcomponent, alpha polypeptide | 3.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 |

| NM_008147 | glycoprotein 49 A | 2.7 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| NM_008176 | Cxcl1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| NM_008327 | lfi202b | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| NM_008677 | neutrophil cytosolic factor 4 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| NM_009140 | cxcl2 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| NM_009285 | stanniocalcin 1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| NM_009663 | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein | 1.8 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| NM_009777 | complement component 1, q subcomponent, beta polypeptide | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| NM_009876 | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (P57) | −0.8 | −0.9 | −0.8 |

| NM_009898 | coronin, actin binding protein 1A | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| NM_010016 | CD55 antigen | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| NM_010185 | Fc receptor, IgE, high affinity I, gamma polypeptide | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| NM_010188 | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity III | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| NM_010240 | ferritin light chain 1 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| NM_010545 | CD74 antigen (invariant polypeptide of major histocompatibility complex, class II antigen-associated) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 0.9 |

| coactosin-like 1 (Dictyostelium) | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.2 | |

| NM_010796 | macrophage galactose N-acetyl-galactosamine specific lectin 1 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| NM_011113 | plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| NM_011584 | nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| NM_013590 | lysozyme | 3.1 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| NM_013777 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C13 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| cDNA sequence BC032204, fermitin family homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | |

| NM_022431 | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 6D | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| NM_029097 | ATPase type 13A2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| NM_053214 | Myo1f | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| NM_134158 | Cd300D antigen | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| NM_134158 | Cd300D antigen | 2.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| NM_183168 | pyrimidinergic receptor P2Y, G protein-coupled, 6 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| XM_354744 | MRS2-like, magnesium homeostasis factor (S. cerevisiae) | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| NM_010766 | macrophage receptor with collagenous structure | 0.7 | 2.9 | 1.5 |

Transcripts shown are dysregulated >0.7 log2 fold at all time points in biologically replicate experiments. Boldfaced fold-changes indicate P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Average log2 fold-change of dysregulated transcripts determined by microarray analysis in leg muscle endothelium following 4, 6, and 8 wk of high-fat diet

| RefSeq | Name | 4 wk | 6 wk | 8 wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_009140 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 (Cxcl2) | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| NM_011338 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| NM_013590 | lysozyme | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| NM_017372 | lysozyme | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| NM_010188 | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity III | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| NM_021443 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| NM_010240 | ferritin light chain 1 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.4 |

| NM_010705 | lectin, galactose binding, soluble 3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| NM_010185 | Fc receptor, IgE, high affinity I, gamma polypeptide | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| NM_008327 | interferon activated gene 202B (lfi202b), transcript variant 1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| NM_145509 | RIKEN cDNA 5430435G22 gene | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| NM_009663 | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| NM_024225 | sorting nexin 5 | −0.6 | −0.2 | 1.1 |

| NM_130904 | CD209d antigen | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| NM_011175 | legumain | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| NM_013602 | metallothionein 1 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| NM_008035 | folate receptor 2 (fetal) | −0.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| G protein-coupled receptor 137B | −0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |

| NM_008495 | lectin, galactose binding, soluble 1 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 1.0 |

| NM_133977 | Transferring | 2.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 |

| NM_023142 | actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 1B (Arpc1b) | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| NM_009984 | cathepsin L | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| NM_133792 | lysophospholipase 3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| NM_007621 | carbonyl reductase 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| mannosidase 2, alpha B1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |

| NM_013706 | CD52 antigen | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| NM_010188 | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity III | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| biliverdin reductase B (flavin reductase (NADPH)) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |

| NM_007657 | CD9 antigen | 1.0 | −0.1 | 1.4 |

| NM_007599 | capping protein (actin filament), gelsolin-like | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| RIKEN cDNA 1810019J16 gene | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | |

| NM_007408 | adipose differentiation related protein | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| NM_144904 | ROD1 regulator of differentiation 1 (S. pombe) | −0.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| NM_178772 | arylacetamide deacetylase-like 1 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.7 |

| NM_025468 | SEC11 homolog C (S. cerevisiae) | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.9 |

| NM_153795 | cDNA sequence BC032204 | n.d. | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| NM_028351 | R-spondin 3 homolog (Xenopus laevis) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.7 |

| NM_029295 | chemokine-like factor | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| NM_008704 | expressed in nonmetastatic cells 1, protein | n.d. | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| NM_009930 | Mus musculus collagen, type III, alpha 1 (Col3a1) | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| NM_053082 | tetraspanin 4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| NM_007913 | early growth response 1 | −1.5 | −0.8 | −0.6 |

| NM_009777 | complement component 1, q subcomponent, beta polypeptide | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| NM_010422 | hexosaminidase B | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| NM_026678 | biliverdin reductase A | −0.2 | −0.1 | 1.0 |

| esterase D/formylglutathione hydrolase | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | |

| XM_486478 | ferritin light chain 2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

Transcripts with both >0.70 log2 fold-change and P < 0.1 in biologically replicate experiments after 6 or 8 wk of the diet are shown. Boldfaced fold changes indicate P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Transcripts commonly dysregulated in aortic and skeletal muscle endothelium in response to a high-fat diet

| 4 wk |

6 wk |

8 wk |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RefSeq | Name | M | A | M | A | M | A |

| NM_009777 | C1qb | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| NM_009140 | Cxcl2 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 1.8 |

| NM_009303 | Syngr1 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| NM_009663 | Alox5ap | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| NM_010185 | Fcer1g | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| NM_144797 | Metrnl | 0.8 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| NM_009898 | Coro1a | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| NM_010545 | Cd74 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| NM_011338 | Ccl9 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| NM_013590 | Lyz1 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| NM_010240 | Ftl1 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.8 |

| NM_010188 | Fcgr3 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| NM_010658 | Mafb | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| NM_134158 | Cd300 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.9 |

Transcripts shown demonstrate >0.5 log2 fold dysregulation in aortic endothelium after 4 wk of feeding and in skeletal muscle endothelium after 6 wk. A, aortic endothelium; M, muscle endothelium. Boldfaced fold-changes indicate P < 0.05.

Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (12, 13) was used to identify overrepresented molecular functions based on gene ontology terms derived from the lists of differentially regulated transcripts in aortic and muscle endothelia (Supplemental Table S2). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Ingenuity Systems, accessible at http://www.ingenuity.com) was also used to identify overrepresented biological functions and canonical pathways based on weighted gene coexpression. Biological functions overrepresented during the time course of the feeding and canonical pathways upregulated by 8 wk of feeding in the aortic and muscle endothelium are shown in Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4, respectively. These analyses further reveal the pathways and biology that are shared among the macro vs. microvasculature as well as those which are specific to each vascular bed.

Real-time PCR.

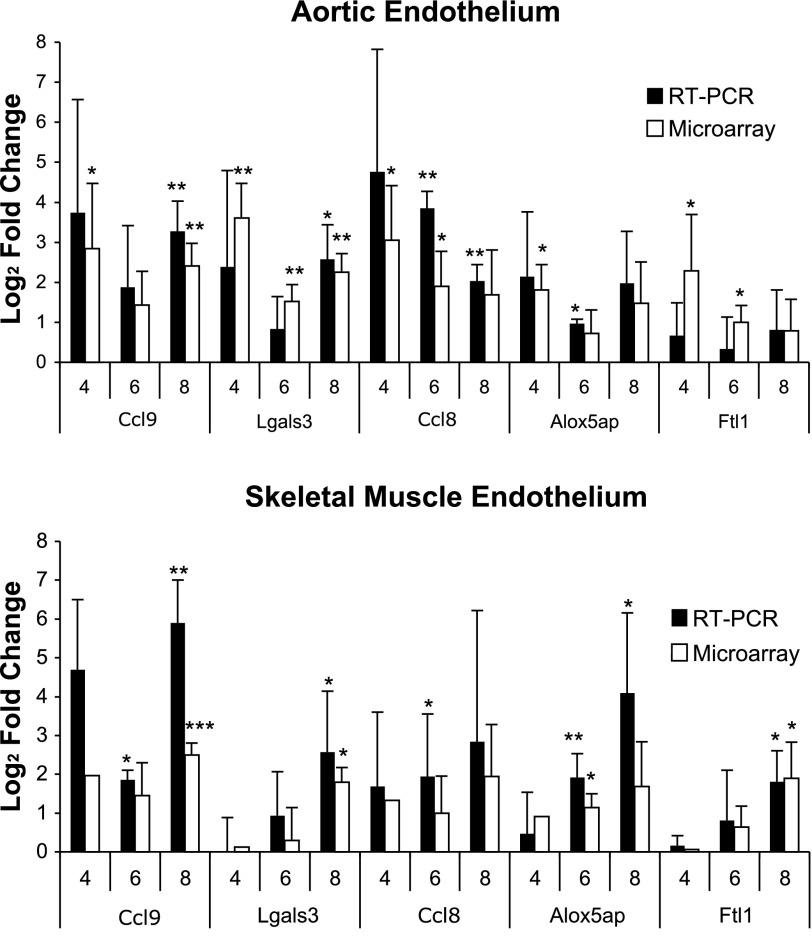

The expression levels of highly dysregulated transcripts were confirmed by real-time PCR. These genes include galectin-3 (Lgals3), C-C chemokines 8 and 9 (Ccl8, Ccl9), 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (Alox5ap), and ferritin light chain 1 (Ftl1). The real-time PCR expression levels of the cDNA transcribed from the cRNA were found to be consistent among biological replicates and in concordance with the microarray data (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Log2 fold-change of endothelial transcripts upregulated by HFD vs. chow diet in Tie2-GFP mice after 4, 6, or 8 wk of feeding as determined by RT-PCR (n = 3–4) and microarray analysis. Data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Increased levels of galectin-3 protein detected in endothelia and sera upon HFD.

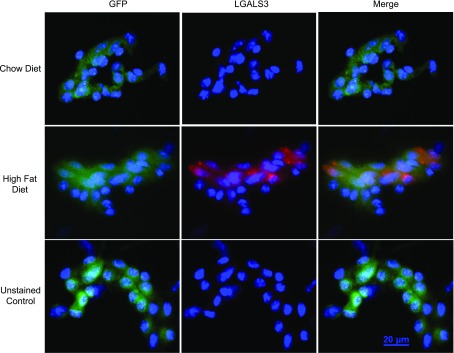

To determine if the increase in galectin-3 mRNA levels in response to HFD led to elevated galectin-3 protein, immunofluorescent staining for LGALS3 was performed on endothelial cells isolated from skeletal muscle. After 8 wk of HFD, the fluorescent signal for intracellular LGALS3 protein in the muscle endothelium increased in response to HFD vs. controls. Representative images of LGALS3 staining are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence staining for galectin-3 protein in FACS-sorted endothelial cells from muscle after 8 wk of HFD or chow diet. Representative images of GFP+ endothelial cells isolated from mice fed either chow (top) or HFD (middle) and stained for LGALS3 or unstained control (bottom).

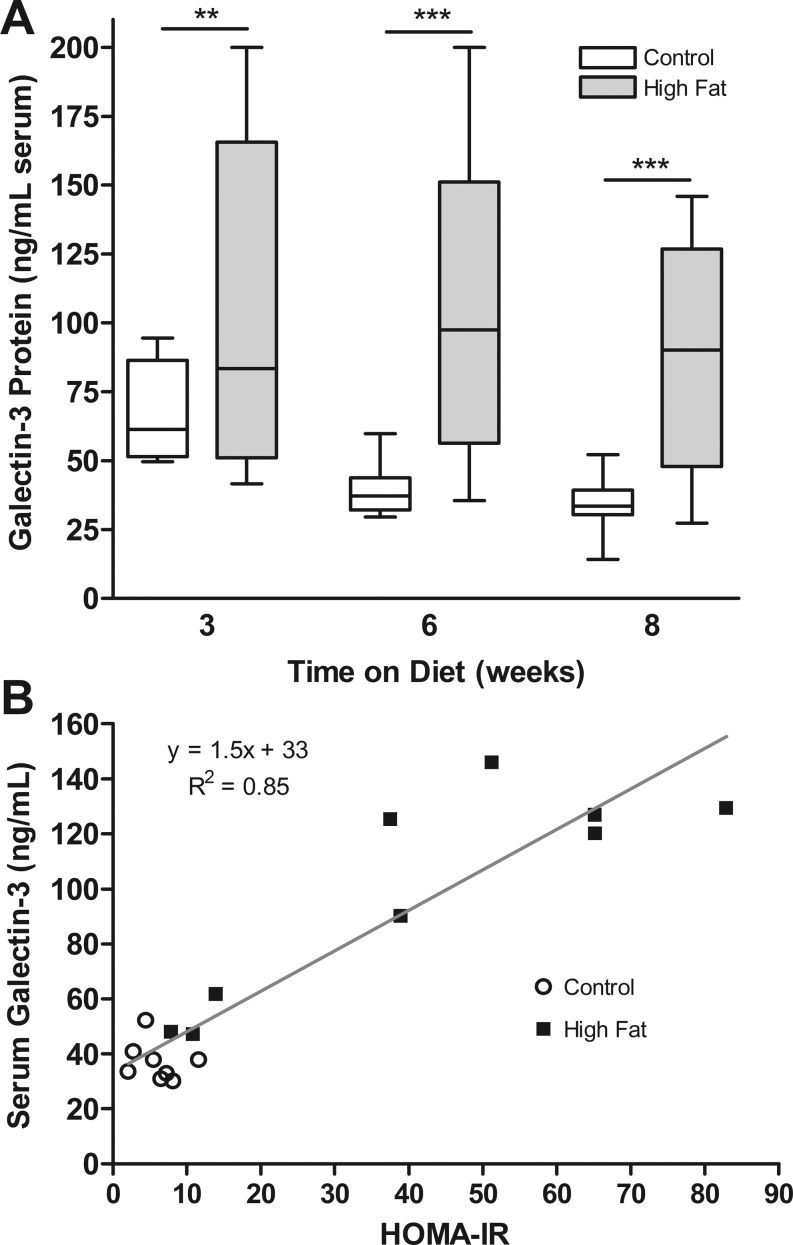

Galectin-3 is a secreted protein normally present in the serum; we therefore evaluated levels of circulating galectin-3. On average, mice receiving the HFD had more galectin-3 in their serum than mice on the control diet (Fig. 4A). Although there was a broad range of galectin-3 levels among high fat-fed mice, average levels were two- to threefold higher in the HFD mice after 6 wk (104.7 ± 17.1 vs. 38.9 ± 2.9 ng/ml, P < 0.005) and 8 wk (90.7 ± 12.3 vs. 34.4 ± 3.4 ng/ml, P < 0.001) on the diet (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, serum galectin-3 levels correlated well with HOMA-IR after 8 wk of feeding, exhibiting a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.92 (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A: galectin-3 soluble protein levels measured by ELISA in serum from mice receiving HFD vs. control for 3, 6, or 8 wk. B: correlation of soluble LGALS3 with HOMA-IR. Data shown as means ± SE (n = 5–11). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we performed a controlled, comprehensive survey of the transcriptional responses of the endothelium in vivo to a model of Type II diabetes induced by a HFD in Tie2-GFP mice. Our mouse model recapitulates clinical diabetes, which is characterized by weight gain, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulemia, and insulin resistance. It is likely that the endothelial dysfunction observed in diabetic patients is a result of the combinatorial effect of these metabolic and hormonal derangements. Our study was not designed to distinguish endothelial responses to any single diabetic change; rather, our analysis integrates all of the diabetic influences on the endothelium, perhaps allowing our assessment to be more physiologically relevant than in vitro studies looking at isolated components of the diabetic milieu.

Our assessment of the endothelial response in both aorta and skeletal muscle addressed the diversity of endothelial cell populations (10) and may thus reflect distinct endothelial contributions to microvascular and macrovascular disease (3). In the present study, we observed a greater response to diet-induced diabetes in the aortic endothelium compared with that of skeletal muscle, as evidenced by both the amount and onset of dysregulation: we identified 36 transcripts with >1.5 log2 fold-change in the large vessel endothelium by 4 wk, whereas the capillary endothelium of the muscle had only 16 transcripts dysregulated to this degree, and in general, only after 8 wk of HFD (Table 3). This difference in susceptibility to transcriptional regulation may represent the foundation for the physiological findings of Kim et al. (19), who observed an earlier onset of vascular vs. peripheral insulin resistance in response to an HFD.

Exploration of the enhanced biological pathways by DAVID and IPA emphasizes the commonalities and differences between the macrovascular and microvascular transcriptional response. Highly upregulated pathways in the aortic endothelium include those related to signaling, including chemokines, PLC signaling, and signaling events that precede atherosclerosis (Supplemental Fig. S4). Interestingly, by 8 wk of HFD, the liver X receptor/retinoic X receptor (LXR/RXR) activation pathway was significantly upregulated in the aortic endothelium (Supplemental Fig. S4). These receptors have been shown to modulate the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in human endothelial cells in vitro (30). Our findings implicate this pathway in the endothelial transcriptional response to an in vivo model of Type II diabetes, and suggests that LXR/RXR agonists may serve a role in modulating lipid metabolism in the macrovasculature. In the microvasculature of the muscle, we observed upregulation of pathways involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements as well as glycolysis and lipid biosynthesis (Supplemental Fig. S4). Biological functions such as molecular transport and “cellular compromise” are overrepresented, including molecules with roles in oxidative stress and cell damage (Supplemental Fig. S3). Other pathways, such as glycerolipid metabolism, and biological functions such as cell-to-cell signaling and interaction and “small molecule biochemistry”, are shared by the two vascular beds (Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4).

Our comprehensive analysis of the transcriptional response of the endothelium to diet-induced diabetes has identified the dysregulation of genes with recognized roles in atherosclerosis, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and inflammation, as well as novel transcripts with previously unknown associations with diabetes. Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 and 8 (Ccl9, Ccl8/Mcp-2) were both found to be dysregulated in aortic and skeletal muscle endothelium. The chemokine CCL9 has recently been suggested as a biomarker of atherosclerosis, and serum protein levels of CCL9 have been closely correlated with gene expression (38). The substantial upregulation of CCL8 may be related to activation of TLR4 by circulating free fatty acids (37) but in any event suggests CCL8 as another potential biomarker of inflammation in diabetes. A catalyst of leukotriene biosynthesis (7), arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (Alox5ap/FLAP), has been implicated in both coronary restenosis and the development of atherosclerosis (9, 17). Endothelial upregulation of Alox5ap upon HFD suggests roles for this protein in vascular inflammation and insulin insensitivity similar to those of 12/15-lipoxygenase (35).

The upregulation of metallothionein 1 (Mt1), a zinc-binding molecule important in maintaining redox homeostasis (4), is consistent with our observed downregulation of early growth response 1 (Egr-1) in the skeletal muscle endothelium; transcription of Egr-1 is regulated by the levels of intracellular zinc (4). Also, ferritin light chain 1 (Ftl1) was upregulated in both muscle and aortae, possibly reflecting the presence of oxidized low-density lipoproteins in diabetic endothelium (16). One other transcript dysregulated in both aortic and skeletal muscle endothelium, lysozyme 1 (Lyz1), is involved in the modulation of AGEs (43) and is a vasodilator (27).

The transcriptional upregulation of another AGE-binding protein, galectin-3/AGE-R3, was also observed in the endothelium of the aorta and the skeletal muscle as shown by microarray and RT-PCR (Table 2, Fig. 2). Galectin-3 is a component of the AGE-receptor complex expressed on the surface of renal cells, including endothelial cells, and is important in the binding and removal of AGEs from the circulation (36). Previous in vitro studies using cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells have demonstrated increased galectin-3 mRNA and protein levels following exposure to AGEs (36). Galectin-3-deficient mice have been shown to display increased glomerular accumulation of AGEs in a model of Type I diabetes and increased ox-LDL and lipoprotein products when fed an atherogenic diet (14, 33). Therefore, the observed marked upregulation of galectin-3 in the aortic endothelia likely reflects elevated AGEs and modified lipids in the diabetic milieu, and suggests a role for galectin-3 in their binding and uptake by the endothelium.

Galectin-3 has been implicated in the progression of cancer due to its antiapoptotic properties, and recent studies suggest that it may contribute to heart failure, possibly due to activation of inflammation and fibrosis (5, 6, 8, 15, 18). A role for galectin-3 in Type I diabetes has been suggested by studies on the Lgals3−/− mouse, which was found to be more resistant to diabetogenesis following STZ treatment and displayed a lower expression of inflammatory cytokines and macrophages with a reduced ability to produce TNF-α and nitric oxide (26). Expression of galectin-3 was shown to be upregulated in whole aortic lysates from both db/db mice and mice exposed to an HFD (28), and elevated galectin-3 mRNA and protein have been demonstrated in the atherosclerotic lesions of ApoE−/− mice (31). In our present study, we observed upregulation of galectin-3 expression specifically in the diabetic endothelium, which places it at the appropriate site to recruit monocytes, in concert with the other inflammatory mediators demonstrated. In vitro studies have shown that exogenous galectin-3 acts as a chemoattractant for monocytes and macrophages through a G protein-coupled pathway, and it can also induce the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (31). Our studies suggest that the increased galectin-3 observed in diabetes and cardiovascular pathologies is at least partially originating from endothelial cells and potentially contributing to vascular inflammation.

We also found that serum galectin-3 levels were substantially increased in our HFD model. A recent study has similarly reported an elevation of systemic galectin-3 in obese and Type II diabetic patients compared with normal weight individuals (42). Thus, our murine model is accurately recapitulating the response of diabetic patients and should be useful to study the role of galectin-3 in the vascular complications of Type II diabetes. Future studies stimulated by our findings could include examining the effects of galectin-3 inhibitors, such as modified citrus pectin, and the effects of diabetic treatments on galectin-3 levels and vascular pathology (21, 29). However, it remains a possibility that some element of circulating galectin-3 is contributed by other cell types such as monocytes and macrophages, which have also been shown to secrete LGALS3 (31, 41).

Another transcript belonging to the galectin family, galectin-1 (Lgals1), was observed to have increased expression in the diabetic skeletal muscle endothelium. LGALS1 may play a role in the adhesion of various cell types to the vascular wall. LGALS1 is expressed on the extracellular surface of endothelial cells and can mediate the adhesion of lymphoma cells to endothelial cells of the liver microvasculature (23). Recently, mass spectroscopic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the plasma of Type II diabetic patients revealed a 4.8-fold increase in galectin-1 protein (22). Galectin-1 also binds the neuropilin-1 receptor on the surface of endothelial cells leading to the increased phosphorylation of the VEGFR-2 co-receptor, which activates the stress-activated protein kinase-1/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase signaling pathway (11) and could influence angiogenesis in diabetic tissues.

Our analysis of the transcriptional response of the endothelium of both aortic and skeletal muscle tissues to an in vivo model of Type II diabetes revealed novel regulation of several transcripts with roles in inflammation, vasoregulation, redox homeostasis, and modulation of responses to AGEs. While a greater number of differentially regulated transcripts were observed in the macrovasculature compared with the microvasculature, commonly dysregulated transcripts were shared by the two vascular beds, suggesting robust and consistent endothelial markers of diabetes. The dysregulated transcripts identified in this study reflect the various metabolic and hormonal derangements that impinge upon the diabetic endothelium and lead to its damage and dysfunction. These findings suggest potential diagnostic biomarkers of the disease and also implicate gene products and pathways that may be targets for the treatment of vascular pathology in Type II diabetes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5P20RR-016453 and 5UH1HL-073449 (to R. V. Shohet), Hawaii Community Foundation Grant 20061485 (to J. G. Maresh), and American Heart Association Predoctoral Award 11PRE7720065 (to A. L. Darrow).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest (financial or otherwise) are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yvonne Baumer for generous assistance with Matrigel and Dil-AcLDL assays and Svenja Meiler for help with flow cytometry data analysis. We also thank Alexandra Gurary of the Molecular and Cellular Immunology Core Facility supported by RCMI (5 G12 RR003061-25) and COBRE (P20RR018727) grants for help with FACS and Steffen Oeser of the Genomics Core for performing real-time PCR and sequencing.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akagiri S, Naito Y, Ichikawa H, Mizushima K, Takagi T, Handa O, Kokura S, Yoshikawa T. A mouse model of metabolic syndrome; increase in visceral adipose tissue precedes the development of fatty liver and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed male KK/Ta mice. J Clin Biochem Nutr 42: 150–157, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker W, Eringa EC, Sipkema P, van Hinsbergh VW. Endothelial dysfunction and diabetes: roles of hyperglycemia, impaired insulin signaling and obesity. Cell Tissue Res 335: 165–189, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cade W. Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys Ther 88: 1322–1335, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colgan SM, Austin RC. Homocysteinylation of metallothionein impairs intracellular redox homeostasis: the enemy within! Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 8–11, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Boer RA, Lok DJ, Jaarsma T, van der Meer P, Voors AA, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ. Predictive value of plasma galectin-3 levels in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Ann Med 43: 60–68, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Boer RA, Yu L, van Veldhuisen DJ. Galectin-3 in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 7: 1–8, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans JF, Ferguson AD, Mosley RT, Hutchinson JH. What's all the FLAP about?: 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein inhibitors for inflammatory diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29: 72–78, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glinsky VV, Kiriakova G, Glinskii OV, Mossine VV, Mawhinney TP, Turk JR, Glinskii AB, Huxley VH, Price JE, Glinsky GV. Synthetic galectin-3 inhibitor increases metastatic cancer cell sensitivity to taxol-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasia 11: 901–909, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiden U, Maier A, Bilban M, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Wadsack C, Lang I, Dohr G, Desoye G. Insulin control of placental gene expression shifts from mother to foetus over the course of pregnancy. Diabetologia 49: 123–131, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho M, Yang E, Matcuk G, Deng D, Sampas N, Tsalenko A, Tabibiazar R, Zhang Y, Chen M, Talbi S, Ho YD, Wang J, Tsao PS, Ben-Dor A, Yakhini Z, Bruhn L, Quertermous T. Identification of endothelial cell genes by combined database mining and microarray analysis. Physiol Genomics 13: 249–262, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh SH, Ying NW, Wu MH, Chiang WF, Hsu CL, Wong TY, Jin YT, Hong TM, Chen YL. Galectin-1, a novel ligand of neuropilin-1, activates VEGFR-2 signaling and modulates the migration of vascular endothelial cells. Oncogene 27: 3746–3753, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 1–13, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iacobini C, Menini S, Ricci C, Scipioni A, Sansoni V, Cordone S, Taurino M, Serino M, Marano G, Federici M, Pricci F, Pugliese G. Accelerated lipid-induced atherogenesis in galectin-3-deficient mice: role of lipoxidation via receptor-mediated mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 831–836, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iurisci I, Tinari N, Natoli C, Angelucci D, Cianchetti E, Iacobelli S. Concentrations of galectin-3 in the sera of normal controls and cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 6: 1389–1393, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang MK, Choi MS, Park YB. Regulation of ferritin light chain gene expression by oxidized low-density lipoproteins in human monocytic THP-1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 265: 577–583, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jawien J, Gajda M, Rudling M, Mateuszuk L, Olszanecki R, Guzik TJ, Cichocki T, Chlopicki S, Korbut R. Inhibition of five lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP) by MK-886 decreases atherosclerosis in apoE/LDLR-double knockout mice. Eur J Clin Invest 36: 141–146, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson KD, Glinskii OV, Mossine VV, Turk JR, Mawhinney TP, Anthony DC, Henry CJ, Huxley VH, Glinsky GV, Pienta KJ, Raz A, Glinsky VV. Galectin-3 as a potential therapeutic target in tumors arising from malignant endothelia. Neoplasia 9: 662–670, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim F, Pham M, Maloney E, Rizzo NO, Morton GJ, Wisse BE, Kirk EA, Chait A, Schwartz MW. Vascular inflammation, insulin resistance, and reduced nitric oxide production precede the onset of peripheral insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1982–1988, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota Y, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, Lawley TJ. Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures. J Cell Biol 107: 1589–1598, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu HY, Huang ZL, Yang GH, Lu WQ, Yu NR. Inhibitory effect of modified citrus pectin on liver metastases in a mouse colon cancer model. World J Gastroenterol 14: 7386–7391, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Feng Q, Chen Y, Zuo J, Gupta N, Chang Y, Fang F. Proteomics-based identification of differentially-expressed proteins including galectin-1 in the blood plasma of type 2 diabetic patients. J Proteome Res 8: 1255–1262, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lotan R, Belloni PN, Tressler RJ, Lotan D, Xu XC, Nicolson GL. Expression of galectins on microvessel endothelial cells and their involvement in tumour cell adhesion. Glycoconj J 11: 462–468, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maresh JG, Shohet RV. In vivo endothelial gene regulation in diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 7: 8, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maresh JG, Xu H, Jiang N, Shohet RV. In vivo transcriptional response of cardiac endothelium to lipopolysaccharide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1836–1841, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mensah-Brown EP, Al Rabesi Z, Shahin A, Al Shamsi M, Arsenijevic N, Hsu DK, Liu FT, Lukic ML. Targeted disruption of the galectin-3 gene results in decreased susceptibility to multiple low dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice. Clin Immunol 130: 83–88, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mink SN, Kasian K, Santos Martinez LE, Jacobs H, Bose R, Cheng ZQ, Light RB. Lysozyme, a mediator of sepsis that produces vasodilation by hydrogen peroxide signaling in an arterial preparation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1724–H1735, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mzhavia N, Yu S, Ikeda S, Chu TT, Goldberg I, Dansky HM. Neuronatin: a new inflammation gene expressed on the aortic endothelium of diabetic mice. Diabetes 57: 2774–2783, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nangia-Makker P, Hogan V, Honjo Y, Baccarini S, Tait L, Bresalier R, Raz A. Inhibition of human cancer cell growth and metastasis in nude mice by oral intake of modified citrus pectin. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 1854–1862, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norata GD, Ongari M, Uboldi P, Pellegatta F, Catapano AL. Liver X receptor and retinoic X receptor agonists modulate the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in human endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med 16: 717–722, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Papaspyridonos M, McNeill E, de Bono JP, Smith A, Burnand KG, Channon KM, Greaves DR. Galectin-3 is an amplifier of inflammation in atherosclerotic plaque progression through macrophage activation and monocyte chemoattraction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 433–440, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potenza MA, Gagliardi S, Nacci C, Carratu MR, Montagnani M. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem 16: 94–112, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugliese G, Pricci F, Iacobini C, Leto G, Amadio L, Barsotti P, Frigeri L, Hsu DK, Vlassara H, Liu FT, Di Mario U. Accelerated diabetic glomerulopathy in galectin-3/AGE receptor 3 knockout mice. FASEB J 15: 2471–2479, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritchie SA, Ewart MA, Perry CG, Connell JM, Salt IP. The role of insulin and the adipocytokines in regulation of vascular endothelial function. Clin Sci (Lond) 107: 519–532, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sears DD, Miles PD, Chapman J, Ofrecio JM, Almazan F, Thapar D, Miller YI. 12/15-lipoxygenase is required for the early onset of high fat diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in mice. PLoS One 4: e7250, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stitt AW, He C, Vlassara H. Characterization of the advanced glycation end-product receptor complex in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 256: 549–556, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Struyf S, Proost P, Vandercappellen J, Dempe S, Noyens B, Nelissen S, Gouwy M, Locati M, Opdenakker G, Dinsart C, Van Damme J. Synergistic up-regulation of MCP-2/CCL8 activity is counteracted by chemokine cleavage, limiting its inflammatory and anti-tumoral effects. Eur J Immunol 39: 843–857, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabibiazar R, Wagner RA, Deng A, Tsao PS, Quertermous T. Proteomic profiles of serum inflammatory markers accurately predict atherosclerosis in mice. Physiol Genomics 25: 194–202, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venneri MA, De Palma M, Ponzoni M, Pucci F, Scielzo C, Zonari E, Mazzieri R, Doglioni C, Naldini L. Identification of proangiogenic TIE2-expressing monocytes (TEMs) in human peripheral blood and cancer. Blood 109: 5276–5285, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber KB, Shroyer KR, Heinz DE, Nawaz S, Said MS, Haugen BR. The use of a combination of galectin-3 and thyroid peroxidase for the diagnosis and prognosis of thyroid cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 122: 524–531, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber M, Sporrer D, Weigert J, Wanninger J, Neumeier M, Wurm S, Stogbauer F, Kopp A, Bala M, Schaffler A, Buechler C. Adiponectin downregulates galectin-3 whose cellular form is elevated whereas its soluble form is reduced in type 2 diabetic monocytes. FEBS Lett 583: 3718–3724, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weigert J, Neumeier M, Wanninger J, Bauer S, Farkas S, Scherer MN, Schnitzbauer A, Schäffler A, Aslanidis C, Schölmerich J, Buechler C. Serum galectin-3 is elevated in obesity and negatively correlates with glycosylated hemoglobin in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 1404–1411, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng F, Cai W, Mitsuhashi T, Vlassara H. Lysozyme enhances renal excretion of advanced glycation endproducts in vivo and suppresses adverse age-mediated cellular effects in vitro: a potential AGE sequestration therapy for diabetic nephropathy? Mol Med 7: 737–747, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou J, Deo BK, Hosoya K, Terasaki T, Obrosova IG, Brosius FC, 3rd, Kumagai AK. Increased JNK phosphorylation and oxidative stress in response to increased glucose flux through increased GLUT1 expression in rat retinal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 3403–3410, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zieman SJ, Kass DA. Advanced glycation endproduct crosslinking in the cardiovascular system: potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Drugs 64: 459–470, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou MH, Cohen R, Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite and vascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Endothelium 11: 89–97, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.