Abstract

The prevalence and type diversity of human astroviruses (HAstV) in children with symptomatic and asymptomatic infections were determined in five localities of Mexico. HAstV were detected in 4.6 (24 of 522) and 2.6% (11 of 428) of children with and without diarrhea, respectively. Genotyping of the detected strains showed that at least seven (types 1 to 4 and 6 to 8) of the eight known HAstV types circulated in Mexico between October 1994 and March 1995. HAstV types 1 and 3 were the most prevalent in children with diarrhea, although they were not found in all localities studied. HAstV type 8 was found in Mexico City, Monterrey, and Mérida; in the last it was as prevalent (40%) as type 1 viruses, indicating that this astrovirus type is more common than previously recognized. A correlation between the HAstV infecting type and the presence or absence of diarrheic symptoms was not observed. Enteric adenoviruses were also studied, and they were found to be present in 2.3 (12 of 522) and 1.4% (6 of 428) of symptomatic and asymptomatic children, respectively.

Human astroviruses (HAstV) are recognized as a common cause of infantile gastroenteritis worldwide (5, 27). The astrovirus virions are 28- to 34-nm-diameter nonenveloped particles which were first described in 1975 (1; C. R. Madeley and B. P. Cosgrove, Letter, Lancet ii:124, 1975). Epidemiological studies carried out in different locations in the world have reported astrovirus prevalence rates of 2 to 16% among children hospitalized with diarrhea and 5 to 17% among children with diarrhea in community-based studies (27).

HAstV belong to the family Astroviridae, which contains a single genus, Astrovirus (26). The HAstV genome is a polyadenylated plus-strand RNA molecule of ∼7 kb organized in three open reading frames (ORFs): ORF1a and ORF1b, at the 5′ end of the genome, code for the nonstructural viral proteins, while ORF2, at the 3′ end, encodes the capsid proteins (8). Based on the nucleotide and encoded amino acid sequences of either the amino-terminal or carboxy-terminal region of ORF2, these viruses have been grouped into eight genotypes (11, 16), which have been shown to completely correlate with the eight established HAstV serotypes (9, 10, 12, 24, 28; J. B. Kurtz and T. W. Lee, Letter, Lancet ii:1405, 1984). Typing surveys indicate that HAstV type 1 (HAstV-1) is the most prevalent, types 2 to 4 are common, and types 5 to 7 are less common, while type 8 has only recently been identified (4-6, 14, 15, 21). These studies have shown that it is not uncommon to find two or more astrovirus types circulating in one region during a given period of time, and they have also described variations in the prevalent astrovirus type with time (6, 10, 14, 15, 21, 22, 28).

The prevalence of HAstV in children with no diarrheic symptoms has also been determined, although in a more limited number of studies. The viruses have been found in ∼2.0% of the children analyzed (2, 3, 7, 25, 28); however, the astrovirus types associated with the asymptomatic infections have not been characterized.

In this study, we have determined the frequency of HAstV infection in diarrheic and nondiarrheic children in five different localities in Mexico, the genotype diversity of the HAstV strains associated with symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, and the genetic diversity (Gd) of these strains. We also evaluated the coinfection of astroviruses with adenovirus types 40 and 41 and with rotaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stool specimens.

The samples included in this work were part of a larger study designed to determine the antigenic diversity of rotavirus strains circulating in Mexico during the period from October 1994 to March 1995 (13, 18). Two groups of samples were analyzed. The first group comprised 710 rotavirus-negative specimens, 355 from diarrheic (symptomatic) and 355 from nondiarrheic (asymptomatic) children. The second group comprised 240 rotavirus-positive stools from 167 symptomatic and 73 asymptomatic children. The symptomatic samples were collected from infants admitted to hospitals or outpatient clinics for acute diarrhea, while asymptomatic children from the outpatient clinics were included when they requested medical attention for diseases other than diarrhea (13). This study was carried out in five different geographic locations: Mexico City; Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala; San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí; Monterrey, Nuevo León; and Mérida, Yucatán.

Detection of astrovirus and adenovirus types 40 and 41.

Fecal specimens were tested for the presence of astroviruses and enteric adenoviruses by using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (IDEIA-astrovirus [Dako Diagnostics] and Premiere Adenoclone, Type 40/41 [Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.]).

Immunoelectron microscopy.

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed essentially as described by Lee and Kurtz (10). Briefly, a 10% extract of feces was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.3 and clarified by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. After being drained, the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of distilled water containing 100 μg of bacitracin/ml. Then, immunoelectron microscopy was carried out by mixing 4 μl of a 1:100 dilution of rabbit sera to HAstV serotypes 1 to 7 (obtained from T. W. Lee and J. B. Kurtz, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom) with 4 μl of the virus suspension on a small piece of Parafilm “M” (American National Can). This was incubated in a moist chamber at 37°C for 1 h. During this period, Formvar-carbon-coated grids were placed onto drops of protein A solution (10 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline) and left at room temperature for 20 min. They were then drained, rinsed three times in distilled water, and placed onto the virus-antiserum mixture. After 10 min of adsorption at room temperature, the grids were again washed three times in distilled water, stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid, pH 7.0, and examined in a Zeiss EM-900 electron microscope at a magnification of ×50,000.

RNA extraction and PCR amplification of the 3′-terminal region of HAstV ORF2.

Total RNA was isolated directly from fecal samples. The feces were diluted to a 10 to 20% concentration with a phosphate-buffered saline solution (pH 7.2), extracted with fluorotrichloromethane (Freon 11; Aldrich), and ultracentrifuged (55,000 rpm; TLA 100.2 rotor; OPTIMA TLX ultracentifuge; Beckman Instruments, Inc.) for 40 min at 4°C. The RNA in the pellet was extracted with trizol (Trizol reagent; GIBCO BRL) and resuspended in 10 μl of sterile water. The viral RNA was used as a template to amplify the ORF2 3′-terminal region by reverse transcriptase PCR. The first cDNA strand was synthesized at 42°C for 50 min using 1 μl of template RNA, 1 μM primer End, and 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (20) in 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 20 U of SuperScript RNase H− reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL). The primers used for PCR were End and Beg (20) for genotypes 1 to 3 and 5 to 8 and Beg-4 (5′-GGGCTTGAGGAGGATCAAAC-3′, nucleotides 1957 to 1976 in HAstV-4 [GenBank accession number Z33883] ORF2) and End for genotype 4 viruses. The PCR was performed in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μl of cDNA, 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Inc.), 2.5 μM PCR primers, and 0.32 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The amplification conditions were 1 min at 94°C, 35 amplification cycles (94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 25 s), and 15 min at 72°C. The expected PCR fragment sizes were 241 bp for genotypes 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8; 217 bp for genotype 6; and 362 bp for genotype 4. The PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels and detected by ethidium bromide staining.

Astrovirus genotyping.

The purified PCR amplicons were sequenced with an ABI Prism automatic DNA sequencer, model 377-18 (Perkin-Elmer). The nucleotide and amino acid sequences obtained in the present work, together with the sequences in data banks whose accession numbers are listed below, were aligned by ClustalX analysis (ftp://ftp-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/pub/ClustalX/). For HAstV-1, the sequences were L23513 (1-Oxf), Y08627 (1-Nor/UK), S68561 (1-New), AF395734 (1-Hun-a), AF395733 (1-Hun-b), AY094088 (1-Safr-a), AY094086 (1-Safr-b), AY094082 (1-Safr-c), AY094081 (1-Safr-d), AY094080, (1-Safr-e), AY093655 (1-Safr-f), AY093654 (1-Safr-g), AY093652 (1-Safr-h), AF257225 (1-SPM-a), and AF257222 (1-SPM-b). For HAstV-2, the sequences were L06802 (2-Oxf), Y08628 (2-Nor/UK), AY094085 (2-Safr-a), AY094084 (2-Safr-b), AY094079 (2-Safr-c), AF257229 (2-SPM-a), and AF257226 (2-SPM-b). For HAstV-3, the sequences were AF141381 (3-Ber), AF257223 (3-SPM-a), AF257227 (3-SPM-b), AF395735 (1-Hun), AY094090 (3-Safr-a), AY094087 (3-Safr-b), AY093650 (3-Safr-c), Y08629 (3-Nor/UK), and AF117209 (3-USA). For HAstV-4, the sequences were Z33883 (4-Oxf), AF395736 (4-Hun), AF257228 (4-SPM), AB025812 (4-Jap-a), AB025811 (4-Jap-b), AB025801 (4-Jap-c), AB025803 (4-Jap-d), AB025802 (4-Jap-e), AB025809 (4-Jap-f), AB025808 (4-Jap-g), AB025807 (4-Jap-h), AB025805 (4-Jap-i), AB025804 (4-Jap-j), AB025806 (4-Jap-k), AB025810 (4-Jap-l), AY094092 (4-Safr), and Y08630 (4-Nor/UK). For HAstV-5, the sequences were U15136 (5-Oxf), AB037274 (5-Chi-a), AB037273 (5-Chi-b), AF395737 (5-Hun), Y08631 (5-Nor/UK), AY094089 (5-Safr-a), AY093651 (5-Safr-b), and AF257224 (5-SPM). For HAstV-6, the sequences were Z46658 (6-Oxf), AB031031 (6-Jap-a), AB031030 (6-Jap-b), and AY093653 (6-Safr). For HAstV-7, the sequences were AF248738 (7-Oxf), Y08632 (7-Nor/UK), AY094091 (7-Safr), and AF257221 (7-SPM). For HAstV-8, the sequences were Z66541 (8-RU), AF395738 (8-Hun), AF292079 (8-Safr-a), AY094083 (8-Safr-b), AY093649 (8-Safr-c), and AF260508 (Mer-8). The nomenclature in parentheses is used in the figures to identify the virus strains (see the legend to Fig. 1 for an explanation of the abbreviations).

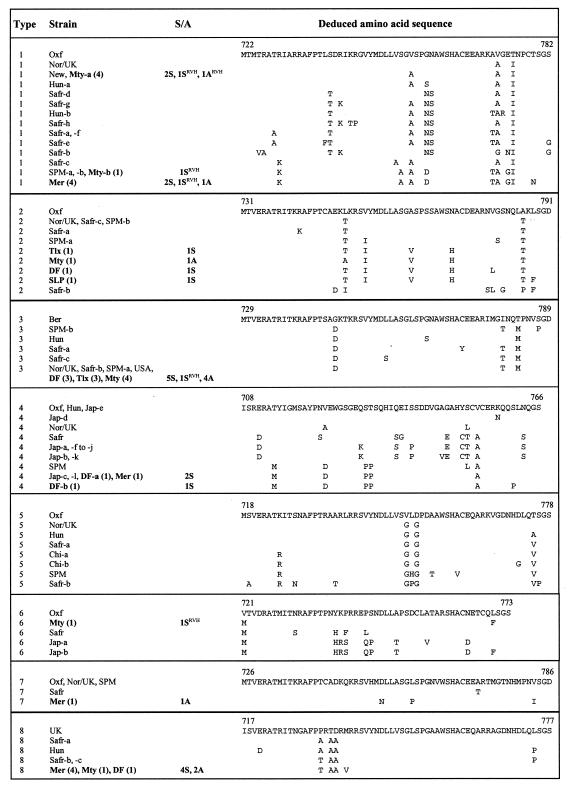

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the carboxy-terminal region of ORF2 from different HAstV types. The sequences within a given type are aligned with a reference strain of known serotype. The 34 HAstV sequences characterized in the present study, isolated from both rotavirus-negative and rotavirus-positive samples, are included in this alignment, together with all sequences reported for this region from HAstV isolated from different parts of the world. The names of the corresponding Mexican astrovirus strains are shown in boldface. Shown in parentheses are the numbers of HAstV strains found in this study having identical sequences. The column S/A indicates whether the HAstV strains were isolated from symptomatic (S) or asymptomatic (A) children. The superscript RVH indicates that the corresponding astrovirus strain was identified in a rotavirus-positive sample. The sequence numbering is according to the ORF2 polyprotein sequence of each reference strain. Empty spaces indicate amino acid identity. Ber, HAstV strains from Berlin, Germany; Chi, strains from China; DF, strains from Mexico City, Mexico; Hun, strains from Hungary; Jap, strains from Japan; Mer, strains from Mérida, Mexico; Mty, strains from Monterrey, Mexico; New, strains from Newcastle, England; Nor/UK, strains from Norway and/or the United Kingdom; Oxf, strains from Oxford, England; Safr, strains from South Africa; SLP, strains from San Luis Potosí, Mexico; SPM, strains from San Pedro Martir, Mexico; Tlx, strains from Tlaxcala, Mexico; UK, strains from the United Kingdom; USA, strains from the United States. The letters a, b, c, etc., identify more than one specimen from the same location.

All listed sequences, including those obtained in the present work, were used to determine the ORF2 3′-end intra- and intertype Gds (Table 1). They were also used to construct the phylogenetic tree with the ClustalX and TreeView (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview/) programs.

TABLE 1.

Gd of ORF2-encoded carboxy-terminal region of HAstV types

| Genotype | Gda for genotype:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| 1 | 0-0.23 | |||||||

| 2 | 0.31-0.48 | 0-0.16 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.33-0.41 | 0.2-0.28 | 0-0.07 | |||||

| 4 | 0.80-0.89 | 0.75-0.84 | 0.79-0.85 | 0-0.24 | ||||

| 5 | 0.43-0.49 | 0.39-0.48 | 0.36-0.43 | 0.77-0.82 | 0.02-0.15 | |||

| 6 | 0.57-0.64 | 0.54-0.59 | 0.56-0.61 | 0.66-0.73 | 0.57-0.61 | 0.04-0.17 | ||

| 7 | 0.36-0.46 | 0.26-0.34 | 0.11-0.18 | 0.77-0.84 | 0.39-0.44 | 0.54-0.59 | 0-0.04 | |

| 8 | 0.41-0.51 | 0.41-0.49 | 0.36-0.41 | 0.74-0.80 | 0.15-0.25 | 0.54-0.62 | 0.40-0.44 | 0-0.08 |

The Gd was calculated as the quotient of the number of amino acid changes divided by the total number of amino acid residues analyzed (61 for types 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8; 59 for type 4; and 53 for type 6). The range of values shown is the result of the intra- and intertype pairwise comparisons of all available sequences.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

HAstV prevalence in symptomatic and asymptomatic children.

During the period from October 1994 to March 1995, stool samples were collected from children <5 years old with and without diarrhea in five locations in Mexico (Mexico City, San Luis Potosí, Tlaxcala, Mérida, and Monterrey). In a previous study, these samples were screened for rotaviruses, which were found to be present in 54 (18) and 7% (unpublished results) of the symptomatic and asymptomatic children, respectively. In this study, the presence of HAstV was investigated by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) in rotavirus-positive and rotavirus-negative samples collected from both symptomatic and asymptomatic children,

A total of 710 samples (355 diarrheic and 355 nondiarrheic) from rotavirus-negative children were screened for astroviruses. The prevalence of HAstV in rotavirus-negative symptomatic children was 5.4% (19 of 355), while 2.5% (9 of 355) of the asymptomatic children were positive for these viruses; the presence of astrovirus particles was confirmed by immunoelectron microscopy in 24 of the 28 EIA-positive samples. To assess the frequency of HAstV in rotavirus-positive children, 240 samples (167 diarrheic and 73 nondiarrheic) were tested. Astroviruses were found in 3% (5 of 167) of the diarrheic samples and in 2.7% (2 of 73) of the nondiarrheic samples. Overall, considering both rotavirus-negative and -positive samples, the frequency of HAstV was 4.6% (24 of 522) in symptomatic children versus 2.6% (11 of 428) in asymptomatic children. In general, a tendency toward association between the presence of HAstV and diarrheic symptoms was observed (χ2 = 2.725; P = 0.099), but it did not reach statistical significance. It is important to mention that we tested a larger percentage of rotavirus-negative (42%) than rotavirus-positive (35%) stools from the original collection of samples (1,091 diarrheic and 1,305 nondiarrheic). Thus, since the rotavirus-negative stools have a higher rate of astrovirus positivity, the extrapolated rates for the original sample set would be 4.1% (45 of 1,091) for diarrheic children and 2.5% (33 of 1,305) for nondiarrheic children.

The prevalence of HAstV in symptomatic children found in this work is similar to the frequency reported from other regions of the world, which has been described as fluctuating between 2 and 16% (2, 4, 14, 19, 22, 23, 25). Likewise, the HAstV prevalence found among the asymptomatic children is also similar to the prevalence of ∼2.0% observed in asymptomatic astrovirus infections in Bangladesh (25), France (2), Guatemala (3), and Thailand (7).

HAstV were found in the five locations studied, indicating that these viruses are widely distributed throughout the country. The prevalence of HAstV varied from 2.6 (San Luis Potosí) to 7% (Mexico City) among the symptomatic patients and from 0 (San Luis Potosí) to 4.1% (Mérida) among the asymptomatic children (data not shown).

Genotype diversity of HAstV strains.

To determine the genomic types (genotypes) of the detected HAstV strains, the 3′-end region of the genome, encoding the 66 carboxy-terminal amino acids encoded by ORF2, was amplified by reverse transcriptase PCR and sequenced. The virus genotype was determined based on this amino acid region but excluding from the analysis the 5 amino acids at the carboxy terminus of the polyprotein, which are conserved among different virus types. This analyzed region has been shown to be variable between strains belonging to different serotypes (11), and phylogenetic analysis of a region somewhat larger than this showed that eight genogroups can be differentiated, with different isolates of the same serotype clustering together, indicating that typing antibodies differentiate among phylogenetically distinct groups defined by the 3′-end sequence of HAstV ORF2 (12, 28).

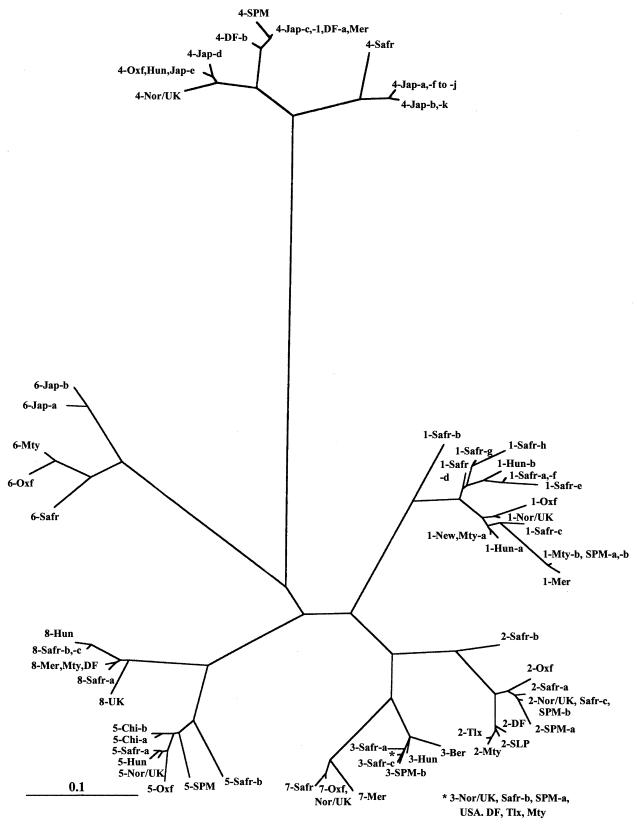

The sequences of 34 (24 from symptomatic children and 10 from asymptomatic children) out of 35 detected HAstV strains were determined. Only one strain could not be sequenced due to the small amount of sample available, but this strain was identified as genotype 4, since the carboxy-terminal ORF2 region was amplified by PCR using serotype-specific primers. Each of the amino acid sequences of the astrovirus strains characterized in this study was related to the sequence of one of the eight known HAstV serotypes (Fig. 1), and phylogenetic analysis of the carboxy-terminal regions of the astrovirus ORF2 polyproteins from all available sequences showed that each of the Mexican isolates clustered with one of the eight described genogroups (Fig. 2). Seven (29%) of the strains from symptomatic children clustered with genotype 1 HAstV strains, six (25%) clustered with genotype 3 strains, four (17%) clustered with genotype 8, three (13%) clustered with genotype 2, and three (13%) clustered with genotype 4 astroviruses. The 11 isolates detected in the samples from asymptomatic children were found to belong to types 1 (2 isolates; 18%), 2 (1 isolate; 9%), 3 (4 isolates; 36%), 4 (1 isolate; 9%), 7 (1 isolate; 9%), and 8 (2 isolates; 18%). Of particular interest was the finding of six genotype 8 strains (four in Mérida, one in Monterrey, and one Mexico City), since this astrovirus type has been detected only sporadically in Australia (14), Egypt (15), South Africa (24), and Spain (6).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the carboxy-terminal region of the polyprotein encoded by ORF2 for the HAstV isolates shown in Fig. 1. Mexican isolates obtained from rotavirus-negative, as well as rotavirus-positive, samples are included. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.1 amino acid residue per position in the sequence. The sequences were obtained from the GenBank database with the accession numbers listed in Materials and Methods.

The genotype diversity of HAstV found in this study, together with the previous detection of HAstV-1 to -5 and -7 in Mexico City (28), indicates that the eight known astrovirus types circulate in Mexico. The high diversity of astrovirus types is not uncommon and has also been reported in countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, Spain, and England (6, 10, 15, 25).

The six HAstV genotypes detected in the asymptomatic controls, with the exception of types 6 and 7, were also found among the symptomatic children. These results suggest that there is not an association between the infecting HAstV type and the presence or absence of diarrheic symptoms, although a larger number of astrovirus strains isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic infants need to be characterized to address this question.

Gd of HAstV.

In order to determine the Gd of the analyzed ORF2 region of HAstV, we calculated the intra- and intertype virus diversity using the deduced amino acid sequences obtained in this work together with those previously reported (Table 1). The Gd was calculated as the quotient of the number of amino acid changes divided by the total number of amino acid residues analyzed (61 for types 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8; 59 for type 4; and 53 for type 6). This analysis showed that the intratype Gd is always lower than that found between different types (Table 1). Despite the fact that in some cases there is a low Gd between viruses that are classified as different types (for instance, types 3 and 7 [Gd, 0.11 to 0.18]), the intratype Gds for type 3 (0 to 0.07) and type 7 (0 to 0.04) viruses are low enough to correctly classify the HAstV strains belonging to these types.

The analysis of the ORF2 amino acid sequences from the astrovirus strains identified in this study showed that in some cases multiple specimens from the same location had identical sequences (Fig. 1). For instance, all HAstV strains belonging to type 1 from Mérida had identical sequences, as was also the case for the type 8 viruses detected in that locality, regardless of whether they were isolated from a symptomatic or asymptomatic patient or obtained from a rotavirus-negative or rotavirus-positive sample; this was also the case for four of the five type 1 astrovirus strains from Monterrey (Mty-a) (Fig. 1). In addition, despite the fact that the type 4 strains have the highest intratype Gd (0 to 0.24) (Table 1), the type 4 viruses detected in this study were all very closely related (Gd, 0.02). Similarly, the sequences of the four identified type 2 strains (Fig. 1, DF, Mty, SLP, and Tlx) differed among themselves at only one or two amino acid positions (Gd, 0.02 to 0.03). HAstV-3 and -8 were the most conserved, as the 10 and 6 strains, respectively, identified for each serotype all had identical sequences intratype, regardless of the city from which they were isolated.

In general, the Mexican HAstV strains belonging to a given type were more similar to each other than to strains of the same type isolated from other parts of the world, with some exceptions. In HAstV-1, almost all Mexican strains that were detected, including those previously reported (28), were very closely related (Gd, 0.02). However, four viruses from Monterrey (Mty-a) had sequences identical to that of a strain from Newcastle, England (New), and had only one amino acid change (Gd, 0.02) compared to strains from Norway-United Kingdom and Hungary (Fig. 1). The type 3 Mexican strains characterized in this study had sequences identical to those of strains from Norway-United Kingdom, the United States, and South Africa, indicating that viruses within this type are highly conserved. The type 4 Mexican strains clustered together with one of the Japanese strains previously characterized (Jap-c; Gd, 0 to 0.02) but clearly differed from other Japanese strains (Gd, 0.08 to 0.17) (Fig. 1 and 2). The single type 6 (Mty) HAstV strain detected was different from other type 6 strains reported from Japan and Hungary and was more closely related to a United Kingdom isolate. The sequence from the type 7 (Mer) astrovirus strain was very similar (Gd, 0.004) to those previously reported from Europe and Africa. Finally, all type 8 strains detected were similar to a South African isolate (Safr-a; Gd, 0.03) and were more distant from the United Kingdom strain (Gd, 0.08).

The low intratype RNA sequence diversity observed in this and a previous work (17) is reflected in the conserved intratype amino acid sequence of the ORF2 region analyzed. This observation, together with the distinct differences among types, suggests that the different astrovirus types diverged a long time ago and supports the idea that serotypes, determined by the reactivities of antibodies, represent phylogenetically distinct groups (12, 17). The low intratype Gd observed might also be useful to trace the origin and movement of HAstV strains around the world.

Geographical distribution of the HAstV types.

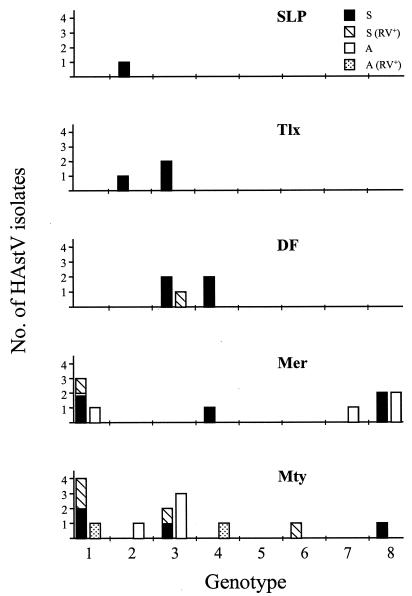

The distribution of the HAstV genotypes varied from one region to another (Fig. 3). The most widely distributed were type 2 astroviruses, which were present in four of the five locations studied. At least two different types were found to cocirculate in each location, with the exception of San Luis Potosí, where only one sample was found to be positive for astrovirus. In symptomatic children, astrovirus types 1 and 3 were the most frequently detected (29 and 25%, respectively). However, they were not present in all locations studied: type 1 viruses were found only in Mérida and Monterrey, while type 3 viruses were detected only in Mexico City, Tlaxcala, and Monterrey. In the case of the asymptomatic strains, the type 3 viruses were the most frequently found (36%), but their distribution was also limited to Monterrey and Mexico City. This sort of heterogeneous distribution of astrovirus types has also been observed in other studies; for instance, in a survey carried out in five regions of Japan, type 1 viruses were present in all locations studied, while the circulation of types 2 and 3, the other two HAstV types identified, was limited to particular locations (21).

FIG. 3.

Geographical distribution of HAstV types identified in Mexican children with symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in five locations in Mexico: DF, Mexico City; SLP, San Luis Potosí; Tlx, Tlaxcala; Mer, Mérida; and Mty, Monterrey. S and A indicate the HAstV strains isolated from symptomatic (S) and asymptomatic (A) children. Astrovirus isolates obtained from both rotavirus-negative and rotavirus-positive samples are included.

Thus, although the eight HAstV types circulate in Mexico, their prevalences vary from one location to another, and they also seems to depend on the period of time evaluated, since in a previous study carried out in a small periurban community in Mexico City it was observed that the HAstV type distribution changed throughout the year (28). Thus, for instance, in a given year type 3 was detected from January to March while type 2 viruses were found from April to August (28). The reasons for the variation in the prevalent HAstV types with time and location are, however, unknown.

Coinfection by astroviruses, rotaviruses, and adenoviruses.

As described above, astroviruses were found in 3% (5 of 167) of the diarrheic samples and in 2.7% (2 of 73) of the nondiarrheic samples from rotavirus-positive children (Fig. 3). Despite the fact that dual infections by human astroviruses and rotaviruses in children with diarrhea are common (2, 4), it is not clear whether infection with one of these viruses favors infection by the second. The observation in this study that astroviruses are found at similar frequencies in both rotavirus-positive and rotavirus-negative diarrheic stools suggests that there is not a synergy between infections by these two viruses.

The presence of enteric adenoviruses was determined by EIA in the same fecal samples that were used for astrovirus detection. Adenoviruses were present in 14 out of the 710 rotavirus-negative samples analyzed. In symptomatic children, 2.8% (10 of 355) of the samples were positive for these viruses, while in asymptomatic children their prevalence was 1.1% (4 of 355). No coinfections between adenoviruses and HAstV were detected. In the rotavirus-positive samples, dual infections by rotaviruses and adenoviruses were found in 1.2 (2 of 167) and 2.7% (2 of 73) of the samples from symptomatic and asymptomatic children, respectively. Overall, adenoviruses were found in 2.3 (12 of 522) and 1.4% (6 of 428) of diarrheic and nondiarrheic samples, respectively.

The astrovirus prevalence rate found in this study was twice as high as that of enteric adenoviruses but much lower than that reported for rotaviruses in the same collection of samples. However, to establish the relative epidemiological importance of these and other gastrointestinal viruses in symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in Mexico, it is important to carry out additional studies that span at least two consecutive years and several different locations in the country.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Eugenio López, Paul Gaytán, and René Hernández for the synthesis of oligonucleotides and DNA sequencing.

This study was partially supported by grants 55003662 and 55000613 from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, IN227602 from DGAPA/UNAM, and MENSE31739 and G37621N from Conacyt-Mexico.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleton, H., and P. G. Higgins. 1975. Viruses and gastroenteritis in infants. Lancet i:1297. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bon, F., P. Fascia, M. Dauvergne, D. Tenenbaum, H. Planson, A. M. Petion, P. Pothier, and E. Kohli. 1999. Prevalence of group A rotavirus, human calicivirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus type 40 and 41 infections among children with acute gastroenteritis in Dijon, France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3055-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz, J. R., A. V. Bartlett, J. E. Herrmann, P. Caceres, N. R. Blacklow, and F. Cano. 1992. Astrovirus-associated diarrhea among Guatemalan ambulatory rural children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1140-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaggero, A., M. O'Ryan, J. S. Noel, R. I. Glass, S. S. Monroe, N. Mamani, V. Prado, and L. F. Avendano. 1998. Prevalence of astrovirus infection among Chilean children with acute gastroenteritis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3691-3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass, R. I., J. Noel, D. Mitchell, J. E. Herrmann, N. R. Blacklow, L. K. Pickering, P. Dennehy, G. Ruiz-Palacios, M. L. de Guerrero, and S. S. Monroe. 1996. The changing epidemiology of astrovirus-associated gastroenteritis: a review. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 12:287-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guix, S., S. Caballero, C. Villena, R. Bartolomé, C. Latorre, N. Rabella, M. Simó, A. Bosch, and R. M. Pinto. 2002. Molecular epidemiology of astrovirus infection in Barcelona, Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrmann, J. E., D. N. Taylor, P. Echeverria, and N. R. Blacklow. 1991. Astroviruses as a cause of gastroenteritis in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 324:1757-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang, B., S. S. Monroe, E. V. Koonin, S. E. Stine, and R. I. Glass. 1993. RNA sequence of astrovirus: distinctive genomic organization and a putative retrovirus-like ribosomal frameshifting signal that directs the viral replicase synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:10539-10543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopmans, M. P., M. H. Bijen, S. S. Monroe, and J. Vinje. 1998. Age-stratified seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies to astrovirus types 1 to 7 in humans in The Netherlands. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:33-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, T. W., and J. B. Kurtz. 1994. Prevalence of human astrovirus serotypes in the Oxford region 1976-92, with evidence for two new serotypes. Epidemiol. Infect. 112:187-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Méndez-Toss, M., P. Romero-Guido, M. E. Munguía, E. Méndez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. Molecular analysis of a serotype 8 human astrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2891-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monceyron, C., B. Grinde, and T. O. Jonassen. 1997. Molecular characterisation of the 3′-end of the astrovirus genome. Arch. Virol. 142:699-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mota-Hernández, F., J. J. Calva, C. Gutiérrez-Camacho, S. Villa-Contreras, C. F. Arias, L. Padilla-Noriega, H. Guiscafré-Gallardo, M. de Lourdes Guerrero, S. López, O. Muñoz, J. F. Contreras, R. Cedillo, I. Herrera, and F. I. Puerto. 2003. Rotavirus diarrhea severity is related to the VP4 type in Mexican children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3158-3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustafa, H., E. A. Palombo, and R. F. Bishop. 2000. Epidemiology of astrovirus infection in young children hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in Melbourne, Australia, over a period of four consecutive years, 1995 to 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1058-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naficy, A. B., M. R. Rao, J. L. Holmes, R. Abu-Elyazeed, S. J. Savarino, T. F. Wierzba, R. W. Frenck, S. S. Monroe, R. I. Glass, and J. D. Clemens. 2000. Astrovirus diarrhea in Egyptian children. J. Infect. Dis. 182:685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noel, J. S., T. W. Lee, J. B. Kurtz, R. I. Glass, and S. S. Monroe. 1995. Typing of human astroviruses from clinical isolates by enzyme immunoassay and nucleotide sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:797-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh, D., and E. Schreier. 2001. Molecular characterization of human astroviruses in Germany. Arch. Virol. 146:443-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padilla-Noriega, L., M. Méndez-Toss, G. Menchaca, J. Contreras, P. Romero-Guido, F. Puerto, H. Guiscafré, F. Mota, I. Herrera, R. Cedillo, O. Muñoz, J. Calva, M. L. Guerrero, B. S. Coulson, H. B. Greenberg, S. López, and C. F. Arias. 1998. Antigenic and genomic diversity of human rotavirus in two consecutive epidemic seasons in Mexico. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1688-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiao, H., M. Nilsson, E. R. Abreu, K. O. Hedlund, K. Johansen, G. Zaori, and L. Svensson. 1999. Viral diarrhea in children in Beijing, China. J. Med. Virol. 57:390-396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito, K., H. Ushijima, O. Nishio, M. Oseto, H. Motohiro, Y. Ueda, M. Takagi, S. Nakaya, T. Ando, R. Glass, et al. 1995. Detection of astroviruses from stool samples in Japan using reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction amplification. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:825-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto, T., H. Negishi, Q. H. Wang, S. Akihara, B. Kim, S. Nishimura, K. Kaneshi, S. Nakaya, Y. Ueda, K. Sugita, T. Motohiro, T. Nishimura, and H. Ushijima. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of astroviruses in Japan from 1995 to 1998 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction with serotype-specific primers (1 to 8). J. Med. Virol. 61:326-331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shastri, S., A. M. Doane, J. Gonzales, U. Upadhyayula, and D. M. Bass. 1998. Prevalence of astroviruses in a children's hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2571-2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shetty, M., T. A. Brown, M. Kotian, and P. G. Shivananda. 1995. Viral diarrhoea in a rural coastal region of Karnataka India. J. Trop. Pediatr. 41:301-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor, M. B., J. Walter, T. Berke, W. D. Cubitt, D. K. Mitchell, and D. O. Matson. 2001. Characterisation of a South African human astrovirus as type 8 by antigenic and genetic analyses. J. Med. Virol. 64:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unicomb, L. E., N. N. Banu, T. Azim, A. Islam, P. K. Bardhan, A. S. Faruque, A. Hall, C. L. Moe, J. S. Noel, S. S. Monroe, M. J. Albert, and R. I. Glass. 1998. Astrovirus infection in association with acute, persistent and nosocomial diarrhea in Bangladesh. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 17:611-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Regenmortel, M. H., C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner. 2000. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, p. 741-746. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 27.Walter, J. E., and D. K. Mitchell. 2000. Role of astroviruses in childhood diarrhea. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 12:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter, J. E., D. K. Mitchell, M. L. Guerrero, T. Berke, D. O. Matson, S. S. Monroe, L. K. Pickering, and G. Ruiz-Palacios. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of human astrovirus diarrhea among children from a periurban community of Mexico City. J. Infect. Dis. 183:681-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]