Abstract

Although site-bound Mg2+ ions have been proposed to influence RNA structure and function, establishing the molecular properties of such sites has been challenging due largely to the unique electrostatic properties of the RNA biopolymer. We have previously determined that, in solution, the hammerhead ribozyme (a self-cleaving RNA) has a high-affinity metal ion binding site characterized by a Kd,app < 10 µM for Mn2+ in 1 M NaCl and speculated that this site has functional importance in the ribozyme cleavage reaction. Here we determine both the precise location and the hydration level of Mn2+ in this site using ESEEM (electron spin–echo envelope modulation) spectroscopy. Definitive assignment of the high-affinity site to the activity-sensitive A9/G10.1 region is achieved by site-specific labeling of G10.1 with 15N guanine. The coordinated metal ion retains four water ligands as measured by 2H ESEEM spectroscopy. The results presented here show that a functionally important, specific metal binding site is uniquely populated in the hammerhead ribozyme even in a background of high ionic strength. Although it has a relatively high thermodynamic affinity, this ion remains partially hydrated and is chelated to the RNA by just two ligands.

Introduction

RNA structure and function depend strongly on ionic conditions. As a negatively charged polyelectrolyte, RNA attracts a diffuse counterion atmosphere.1,2 In addition to this diffuse counterion atmosphere, site-bound Mg2+ and also monovalent cations have been invoked as specific cofactors that stabilize unique RNA folds and influence reactions catalyzed by ribozymes.1–6 It has remained challenging to develop a molecular basis for the influence of specific cations on RNA function, in large part because it is difficult to determine properties of the specific sites. Intuition derived from the properties of metalloproteins would suggest that metal ion cofactors that are critical to biological function would have defined binding sites. In the context of the unique electrostatic properties of folded RNA, however, the properties of specific metal sites may differ substantially from expectations based on metalloproteins.1,2,7,10 Although many monovalent and divalent cations have been modeled as bound to specific RNA ligands in X-ray crystal structures of RNA molecules,1–9 X-ray crystallographic models do not provide the direct link between site population and RNA function under solution conditions that is required to understand the influence of these ions on RNA activity.

Here we report properties of a specific metal ion site in the self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme, including identification of the RNA ligands and hydration level of the ion. This information links thermodynamic and coordination properties of a defined, functional metal ion site in this ribozyme. The methods used in this investigation include functional metal substitution by paramagnetic Mn2+, isotopic substitution of ligands, and ligand identification by electron-spin–echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) spectroscopy.

In metalloproteins, spectroscopic methods have been used extensively to explore the properties of metal coordination sites. These methods have recently been applied to metal interactions with the hammerhead ribozyme (HHRz, Figure 1), a small self-cleaving RNA whose activity in moderate ionic strength is greatly enhanced by addition of divalent ions.4,11 According to crystal structures, both Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions populate several sites in this RNA, including a position defined by a phosphate from A9 and a guanine base at G10.1.12–14 In the initial structure of this motif,14 soaking crystals with Mn2+ or Cd2+ produced additional density only at this site, whereas later X-ray structures of a different HHRz construct modeled in several metal ions.12,13 The A9/G10.1 residues in the HHRz are located in a conserved core of nucleotides that is essential for catalytic activity. This position has been of particular interest, since modifications of these specific residues have been shown to have a profound effect on activity despite the ~20 Å distance from the cleavage site that is predicted by crystallography (Figure 2).11–17

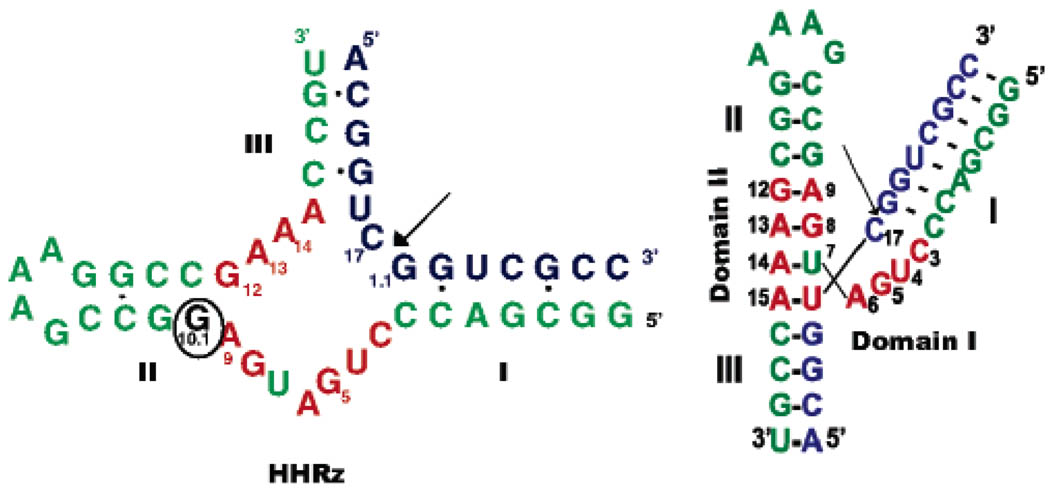

Figure 1.

Hammerhead ribozyme (HHRz) construct used in this study. Nucleotides in red form the conserved core, and the circled G10.1 nucleotide is the site of 2′-deoxyguanosine modification (dG10.1) and specific 15N labeling. Arrow indicates the cleavage site. In samples used for spectroscopy, a 2′methoxy substitution was placed at C17 in the substrate strand to prevent cleavage.

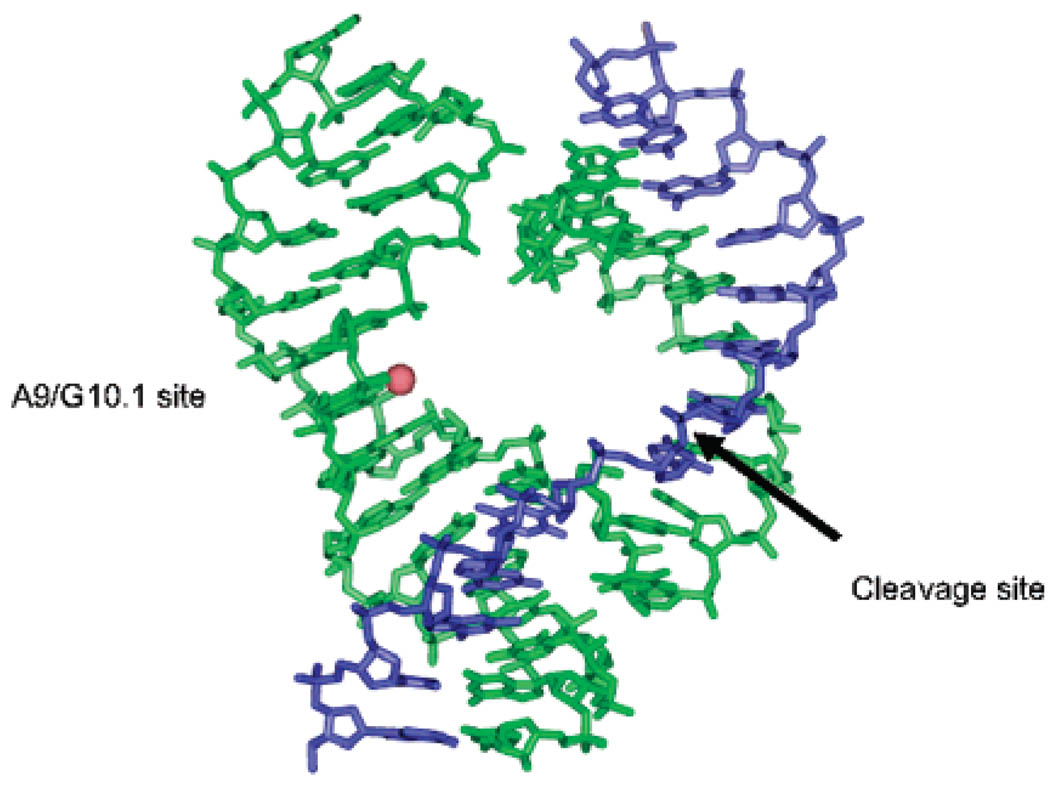

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of Hammerhead ribozyme (PDB 1HMH, ref 14) with a Mn2+ ion (red sphere) placed at the A9/G10.1 site.

Mn2+ is a functional substitute for Mg2+ in the HHRz, providing a useful paramagnetic probe for structural studies utilizing EPR (Electron Paramagnetic Resonance) spectroscopy. 19–25 Occupation of a single high-affinity Mn2+ site in the HHRz in a background of 1 M NaCl was suggested by Mn2+ binding isotherms.20 Low-temperature EPR, ENDOR (electron nuclear double resonance), and ESEEM studies, also performed in high salt concentration, indicate phosphate and nitrogen coordination to the Mn2+ ion, with the nitrogen derived from a guanine ligand in the enzyme strand.21,22,25

Although these studies are consistent with a proposal that the highest affinity HHRz metal ion site is also the functionally important A9/G10.1 site, direct site identification has been lacking. Since purine N7 positions and phosphate are common ligands to metals in nucleic acids, it has remained possible that the high affinity site identified under solution conditions may be any of several possibilities suggested by X-ray crystallography. It is even possible that these spectroscopic signals arise from a distribution of Mn2+ ions over several sites having similar apparent affinities. In this work, site-specific 15N labeling is used to unambiguously identify the high-affinity Mn2+ site in the hammerhead ribozyme as the A9/G10.1 site. ESEEM H2O counting experiments24 are also performed in order to determine the hydration level of Mn2+ in this RNA site. We show that this site is uniquely populated by Mn2+ even in a background of high monovalent ion concentration. Although it has a relatively high thermodynamic affinity, the divalent ion remains partially hydrated and is chelated to the RNA by just two ligands. This work provides a concrete example for an emerging view that the occupation of metal sites in RNA is driven by negative electrostatic potentials that are created by complex folded structures1,2 but that the sites also are influenced by the arrangement of specific ligating residues.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of RNA Strands

RNA oligonucleotides, including 34nt HHRz enzyme (wild type and 2′-deoxyguanosine substituted (dG10.1)) and 13nt substrate (unmodified and 2′-methoxy C17 (OMe)) strands, were purchased from Dharmacon Inc. (Lafayette, CO). All RNA strands were deprotected and gel purified on 20% polyacrylamide gels. The oligonucleotides were then electroeluted and dialyzed at 4 °C against a buffer of 5 mM TEA (triethanolamine), 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8 for at least 48 h with five buffer changes. Samples were concentrated, ethanol-precipitated, and dried. The oligonucleotide pellets were then resuspended in a 5 mM TEA, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.8 buffer. Concentrations were determined by UV/vis absorbance at 260 nm on a Cary 300 Bio UV/vis spectrophotometer (Varian).

The HHRz enzyme strand labeled with a single 15N at dG10.1 was synthesized by Xeragon (Qiagen) using 15N labeled 2′-deoxyguanosine phosphoroamidites (Spectra Stable Isotopes) and purified as described above.

Ribozyme Activity of dG10.1 Modified HHRz

Activity studies were performed as described by Horton et al.20 in 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM TEA, and pH 7.8 under single turnover conditions with an enzyme concentration of 3.2 µM and a substrate concentration of 3 µM. The reaction was quenched by addition of 50 mM EDTA and 8 M urea. The dG10.1 HHRz has a kobs of approximately 4/min at a concentration of 300 µM Mn2+, which is the same as the value reported for the WT HHRz,20 as expected based on previous studies of this modification. 15

EPR Sample Preparation

Equal concentrations of 34nt enzyme strand and 13nt OMe substrate strand were combined, annealed for 90 s at 90 °C, and then cooled on ice for 30 min. MnCl2 was added from a stock solution freshly prepared from a 1 M MnCl2 source (Sigma). Typical sample volumes were 90 or 100 µL and included 20% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol acting as a cryoprotectant. The samples were transferred to quartz EPR tubes (Wilmad) and frozen in liquid N2. The dG10.1 14N sample contained 360 µM Mn2+ and 360 µM HHRz. The wild-type HHRz natural abundance 14N sample contained 400 µM Mn2+ and 400 µM RNA HHRz. The dG10.1 15N sample was prepared with 195 µM Mn2+ and 244 µM RNA HHRz.

Preparation of Deuterated Samples

The ESEEM H2O counting experiments require two samples, one prepared in H2O and the other prepared in 2H2O. For these samples, following ethanol precipitation, both the enzyme and substrate RNA strands were dried by speed vacuum, resuspended in 2H2O or H2O, and lyophilized. The pellet was redissolved in 2H2O or H2O and lyophilized again. This procedure was repeated 3 times. The final RNA pellets were then brought up in a buffer of 1 M NaCl, 5 mM TEA, pH = 7.53 (pD = 7.93) in 2H2O. The EPR samples were prepared as described above, with 350 µM HHRz and 250 µM of Mn2+, with 0.4 M sucrose as the cryoprotectant in either H2O or 2H2O. Samples were then transferred to quartz EPR tubes and frozen in liquid N2.

X-Band EPR Spectroscopy

EPR spectra were obtained at a temperature of 10 K on a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer operating at 9.4 GHz. Typical EPR parameters were 100 kHz modulation frequency, 15 G modulation amplitude, and a microwave power of 0.2 mW. EPR spectra were manipulated using the WinEPR program software suite from Bruker.

ESEEM Spectroscopy

Pulsed EPR spectroscopy was performed on a laboratory built 8–18 GHz spectrometer described previously. 26 Three-pulse ESEEM experiments27,28 measure the T dependence of the stimulated echo amplitude from the π/2−τ −π/2−T−π/2−τ-echo pulse sequence and were analyzed as previously described.22–24 Data were obtained at 4.2 K with a microwave frequency of 9.361 GHz, a repetition rate of 8 ms, and with tau values provided in the figure legends.

To determine the number of water ligands bound to Mn2+ in the HHRz high-affinity metal site, a previously reported “water-counting” procedure was employed.24,29 ESEEM spectra were obtained for samples in both natural-abundance H2O and in 2H2O-exchanged media. The ESE (electron spin–echo) modulation pattern can be approximated as a product of the magnetic interactions from each set of relevant nuclei, where each interaction is related to the number and distance of the nuclei from the paramagnetic center. Thus, ratios of signals from HHRz samples in 2H2O and H2O provide the ESEEM contribution solely from exchangeable deuterium, removing contributions from other nuclei such as 14N and nonexchangeable protons.29 The three-pulse ESEEM experiment allows selection of tau values that diminish background modulation from protons and so has been used extensively for these types of deuterium-quantitation studies.29 Although the product rule applies formally only to two-pulse ESEEM, it is a good approximation for three-pulse ESEEM in the case of small hyperfine and dipolar contributions as expected for deuterium couplings measured in this experiment.29c To remove contributions from solvent molecules not directly coordinated to Mn2+, the ratioed 2H2O/H2O data are subsequently divided by the ESE modulation for Mn2+–diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) in 2H2O, which has no inner-sphere aqua ligands. The resulting HHRz ESEEM data consist solely of 2H modulation from inner-sphere 2H2O ligands. The depth of the deuterium modulation is then compared to data sets that are predicted for N (=1–6) aqua ligands. The predicted data for N = 1–6 aqua ligands are created by raising the 2H ESE data from Mn(2H2O)62+ (divided by the 2H Mn-DTPA ESE signal) to the N/6 power.24 To further control for possible effects of background modulation, ESEEM experiments were repeated with the magnetic field set to three different maxima of the Mn2+ ESE-EPR line shape, typically 3110, 3350, and 3551 G.

Molecular Modeling of the A9/G10.1 Site

A simple molecular mechanics approach was used to model the Mn2+ ion bound at the A9/G10.1 site in the hammerhead. The model was constructed from the HHRz crystal structure PDB 1HMH14 by deleting all bases except G8, A9, and G10.1. The Mn2+ ion was modeled coordinated to the pro-Rp oxygen of the A9 phosphate as predicted by functional,15 X-ray structure,12,13 and spectroscopic21 studies, and the N7 position of G10.1 with four water molecules filling out the coordination sphere as determined from this work. The energy of the truncated model was minimized using the program Cerius2.

Results

Previous activity studies on the HHRz predict a functional Mg2+ site involving A9/G10.1, and spectroscopic studies provide evidence for a high-affinity Mg2+/Mn2+ site in the ribozyme. To definitively link these two observations and describe the properties of this cofactor, HHRz samples were examined by Mn2+ EPR and ESEEM spectroscopies in high salt (1M NaCl) to satisfy nonspecific cation interactions. 15N isotopic substitution of the proposed guanine ligand required the incorporation of 2′-deoxyguanosine at position G10.1, which has minimal effect on activity (see Materials and Methods).

EPR Spectra

The low-temperature EPR spectrum of Mn2+ in the wild-type HHRz sample shows the typical six-line spectrum, centered at g= 2, that results from hyperfine coupling between the unpaired electron spins and the I = 5/2 55Mn nucleus (Figure 3). Compared to Mn2+ in a buffer sample, the WT HHRz sample has a distinct line shape, due to the slightly distorted metal environment, that is most noticeable on the sixth line of the EPR signal. This feature has been previously observed for Mn2+ bound to the WT HHRz and attributed to population of the high affinity metal ion binding site.21 The EPR spectrum for the dG10.1 HHRz shows a feature that is similar, although weaker in amplitude, to that observed for the WT HHRz sample (Figure 3 inset). The change in line shape observed in both Mn2+ HHRz samples relative to the buffer sample can be modeled as being due to a small difference in the zero field splitting (zfs) of the Ms sublevels, which alters the positions of the forbidden transitions and results in more pronounced allowed lines.30

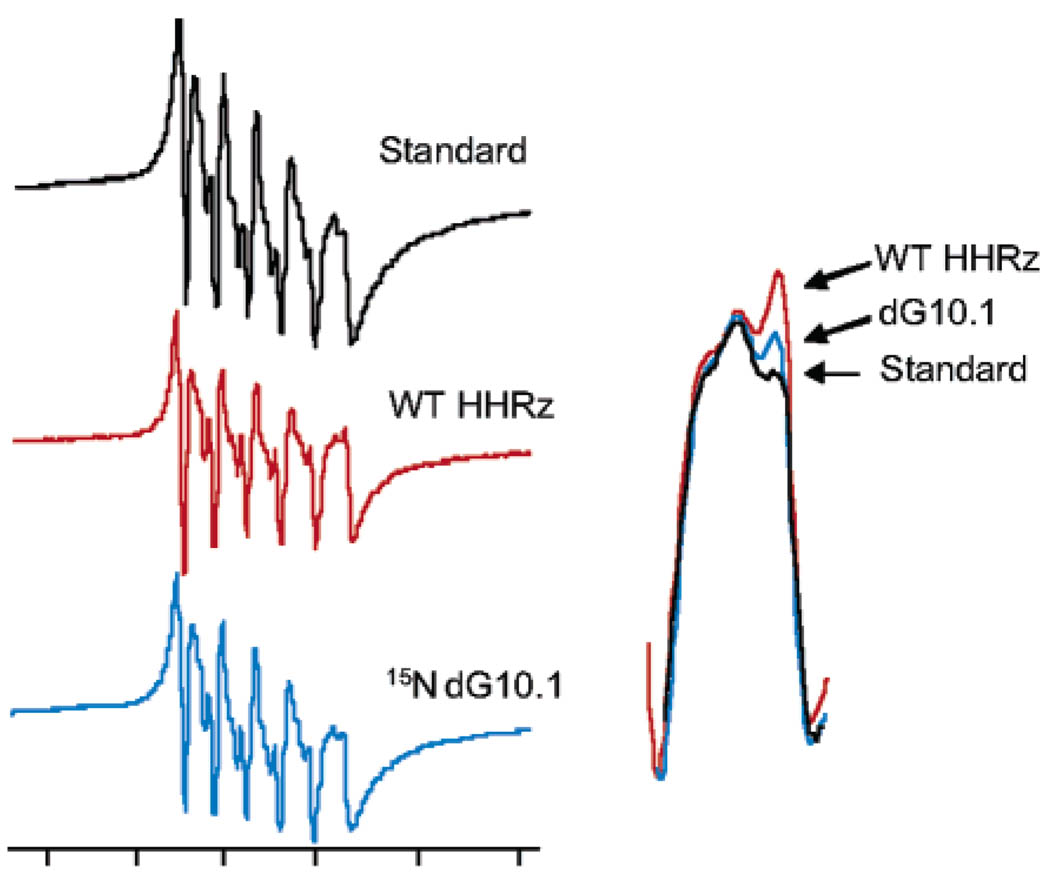

Figure 3.

X-band EPR spectra of Mn2+ bound to hammerhead ribozymes. Inset shows an overlay of the sixth (highest-field) line of the EPR spectra of Mn2+ bound to WT HHRz, HHRz with a dG10.1 substitution, and Mn2+ in a buffer solution (Standard). Spectra were obtained at 10 K, with 250–350 µM HHRz samples in 1 M NaCl, 5 mM TEA, pH = 7.8, and 20% ethylene glycol. EPR instrument conditions were X-band (9.4 GHz), 0.2 mW microwave power, 100 kHz magnetic field modulation at an amplitude of 15 G.

Nucleobase Ligand Identification by 14N/15N ESEEM Spectroscopy

ESEEM spectroscopy is useful in observing weak hyperfine couplings that are not detected in conventional EPR spectra and has been previously used to detect 14N,22,23,25 15N,22,23 and 2H24 coupled to Mn2+ ions bound to RNA or model nucleotides. The three-pulse ESEEM spectrum of Mn2+ in the WT HHRz shown in Figure 4 displays a pattern that has been previously observed for Mn2+ coordinated to the 14N (I = 1) of a guanine ligand.22,23 The set of frequencies observed in these spectra result from the hyperfine and quadrupolar couplings of the 14N I = 1 nucleus.31 This pattern has been observed previously for Mn–GMP complexes, for which Mn coordination is expected through the guanine N7 imino nitrogen. Isotopic substitution in Mn–15N–GMP results in replacement of this pattern with one consistent with the change to an 15N nucleus, with I = ½ and no nuclear quadrupole moment.22,23 Nearly identical spectral changes are observed in the HHRz when the enzyme strand is transcribed using 15N-GTP, resulting in globally labeled 15N-labeled guanines (Figure 4, third trace).22 Thus, for the HHRz these ESEEM data represent coordination of Mn2+ to one or more guanine ligands. Identification of the exact ligand was achieved with site-specific 15N substitution at G10.1.

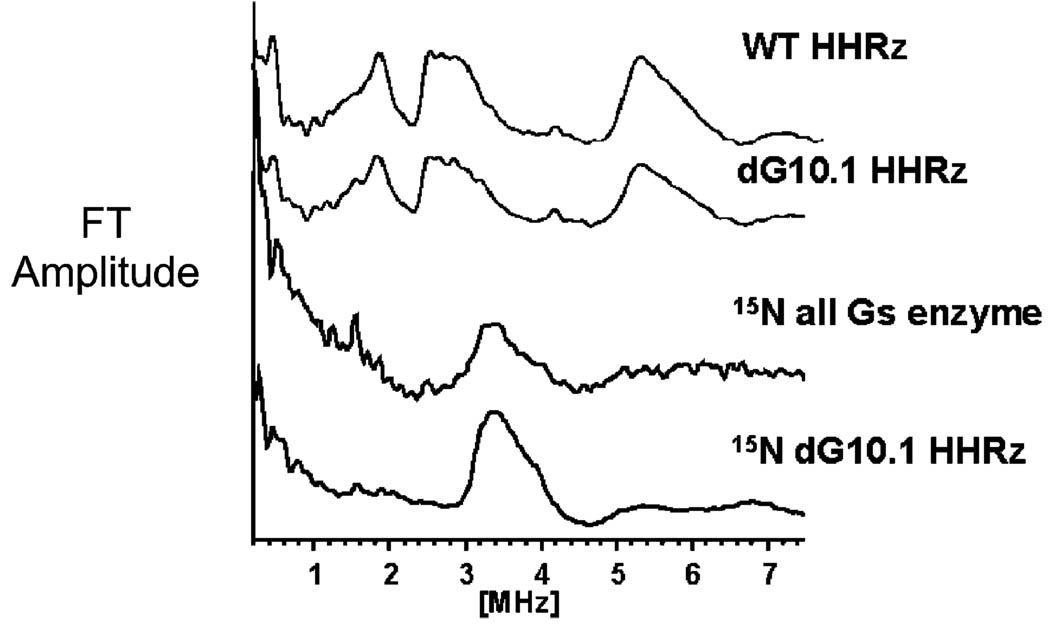

Figure 4.

14/15N three-pulse ESEEM spectra of Mn2+ bound to the hammerhead ribozyme. Wild type and dG10.1 HHRz show similar 14N (I = 1) ESEEM Fourier transform traces, consistent with Mn–guanine coordination. The “15N all G’s enzyme” HHRz, in which all guanines on the enzyme strand are labeled with 15N, shows an ESEEM pattern consistent with Mn–15N (I = ½) coordination.22 A nearly identical spectrum is observed with specific 15N labeling of G10.1, identifying G10.1 as the Mn2+ ligand. Experiment conditions: magnetic field strength 3600 G, tau = 192 ns, η/2 pulse length 15 ns, microwave power 3.2 W.

Mn2+ bound to the natural-abundance HHRz dG10.1 sample gives rise to an 14N ESEEM pattern that is nearly identical to that of the unsubstituted WT HHRz (Figure 4, second trace), indicating that the 2′-deoxyguanosine modification has little effect on the metal binding site. The intensity of the dG10.1 sample ESEEM signal is ~70% that of the WT sample indicating a lowered concentration of bound Mn2+ ions, which is consistent with the slightly lower population of bound Mn2+ suggested by the EPR signal for this sample. With 15N substitution, the ESEEM spectrum from the 15N dG10.1 HHRz sample exhibits a single broad feature at 3.5 MHz (Figure 4, bottom trace), as observed for the globally 15N-labeled HHRz and for Mn–15N–GMP.22 The ESEEM spectrum of the 15N dG10.1 HHRz sample does not show any additional features from 14N coordination, ruling out multiple high-affinity Mn2+ binding sites. The ESEEM spectrum for the HHRz sample in which the enzyme strand contains 15N in all guanine sites shows an additional peak at 1.5 MHz that arises from coupling to distant 15N nuclei and which is absent in the dG10.1 labeled spectrum. Taken together, these data provide conclusive evidence that Mn2+ binds tightly, and homogeneously, to the hammerhead G10.1 site.

Hydration Level of the High-Affinity Mn2+ Ion

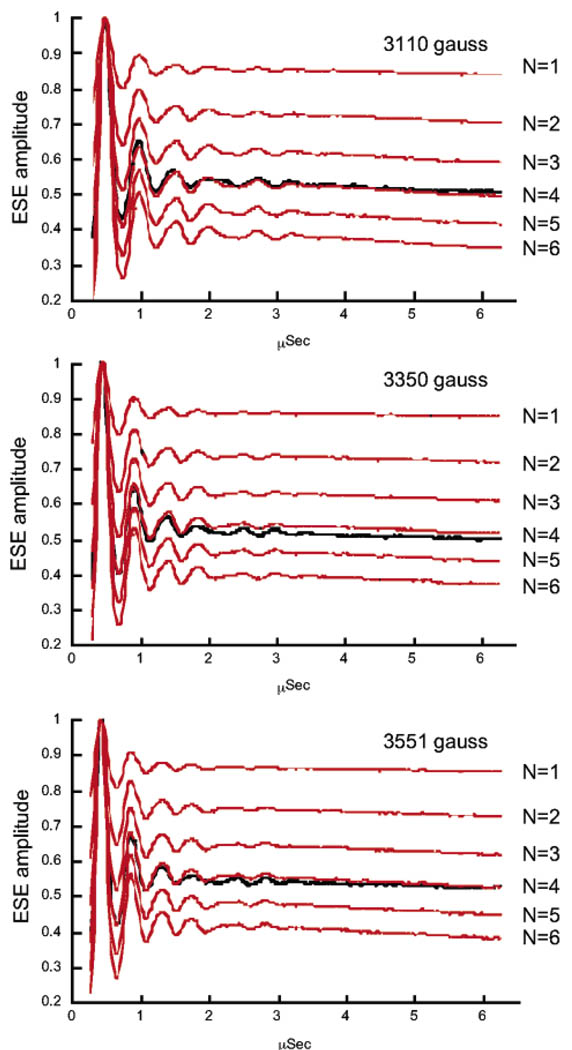

Previous ENDOR studies of Mn2+–HHRz samples demonstrated the presence of coordinated H2O molecules.21 However, such CW ENDOR methods lack the ability to quantify the precise number of aqua ligands bound to the Mn ion. To determine the exact number of H2O molecules coordinated to Mn2+ in the high affinity ribozyme site, Mn2+–HHRz samples were prepared in 2H2O, and 2H ESEEM, which is sensitive to the number of coupled nuclei, was used to determine the number of 2H2O ligands. As described under Materials and Methods, this technique isolates modulation from solvent molecules that are directly coordinated to the Mn2+ ion by a ratio method, using samples prepared in either H2O or 2H2O.24,29 Figure 5 shows 2H ESEEM time-domain traces obtained from Mn2+ bound to 2H2O-exchanged HHRz, appropriately ratioed (black), in comparison with data calculated for different hydration levels that are based on amplitudes obtained using a known standard (red). Data obtained at three different magnetic fields show excellent agreement in deuterium modulation depth. The average of fits to the three data sets results in a value of 4.08 ± 0.12 2H2O ligands, indicating that four aqua ligands are coordinated to the high affinity Mn2+ ion in HHRz.

Figure 5.

Hydration level of the high-affinity Mn2+ site in the hammerhead ribozyme determined by 2H ESEEM spectroscopy. 2H three-pulse ESE time-domain traces from deuterium-exchanged HHRz samples, ratioed by data obtained on natural-abundance HHRz samples (see Materials and Methods), are compared with data calculated for hydration levels of N = 1–6 2H2O Mn2+ ligands. Data are plotted as a function of T (µs) (see Materials and Methods) and were obtained at three different magnetic field values with η values (in parentheses) selected for suppression of proton modulation: 3110 G (228 ns); 3350 G (210 ns); 3551 G (198 ns). The average fit to these data gives a value of 4.08 ± 0.12 H2O molecules coordinated to the HHRz-bound Mn2+ ion.

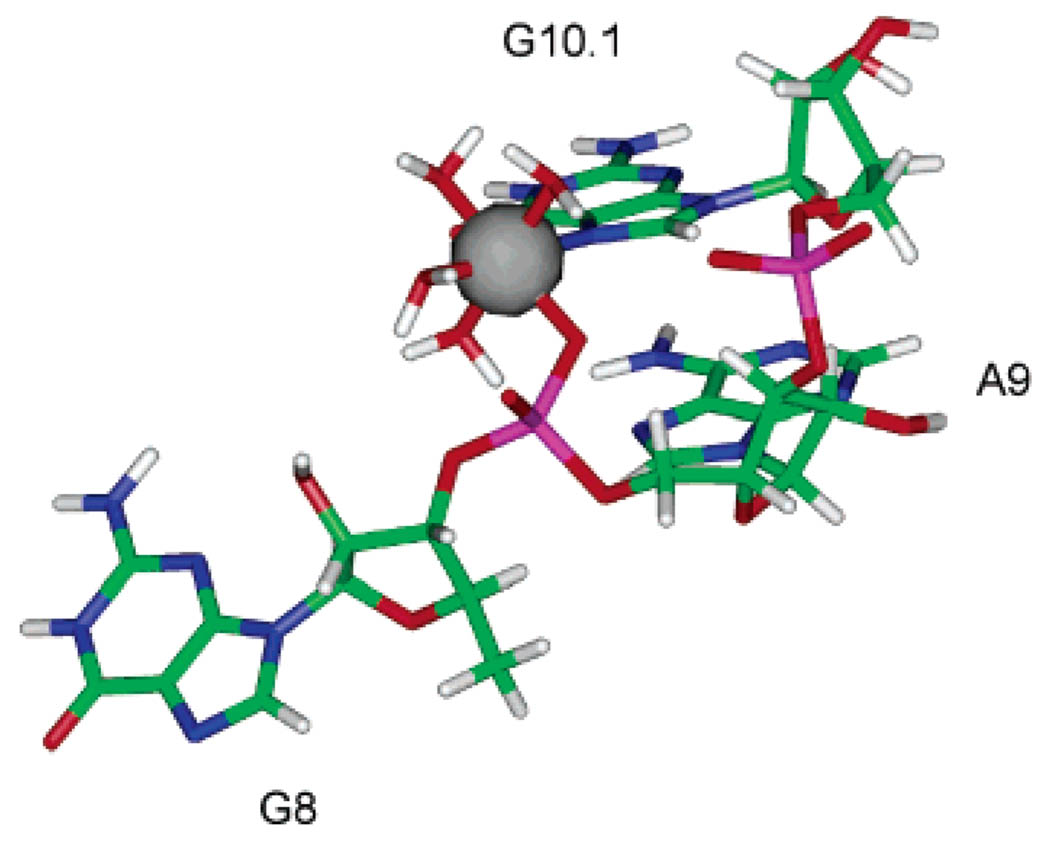

Model of Mn2+ Coordination in the High-Affinity Metal Site

Figure 6 shows a model of the high affinity Mn2+ site in the hammerhead ribozyme that is based on the existing X-ray crystal structure of this construct and the results from EPR/ ESEEM spectroscopy.

Figure 6.

Model of the high affinity A9/G10.1 Mn2+ site in the hammerhead ribozyme, based on energy minimization of Mn2+ complexed to G8, A9, and G10.1 excised from the HHRz X-ray structure 1HMH.14 Specific 15N labeling of the G10.1 site and ESEEM spectroscopy identify the guanine ligand (Figure 4). Previous ENDOR studies predict phosphate coordination.21 This site is proposed to be six-coordinate based on the ESEEM water-counting experiments (Figure 5).

The ligands coordinated to the Mn2+ ion are the pro-Rp oxygen from the phosphate of A9, the N7 from G10.1, and four H2O molecules as determined by the ESEEM H2O counting experiments. In the initial model, Mn2+ was placed into the coordinates of the A9/G10.1 site as excised from the crystal structure of metal-free HHRz (1HMH, ref 14). When Mn2+ is placed coordinated to G10.1 with a reasonable Mn–N distance of 2.2 Å, the starting distance between the Mn2+ ion and the phosphorus atom is approximately 3.9 Å. After energy minimization of the model, the Mn–P distance reduced to 3.2 Å, which is consistent with the 3.3 Å value observed in the crystal structure of Mn–ATP. 33 The remaining RNA structure rearranged only slightly following energy minimization, which suggests that this site has a geometry that favors chelation. The symmetry around the Mn2+ ion in this model deviates from pure octahedral symmetry, which is consistent with the unique line shape of the EPR spectrum observed for Mn–HHRz.

Discussion

A major factor in determining if a metal ion binds to RNA in a diffuse or chelated manner is a balance between energetic terms that are unique to nucleic acids. Draper and co-workers have argued that electrostatic interactions dominate the energetics of RNA–cation association.1,2 They point out that a “site-bound” ion pays an energetic cost by displacing other associated cations and also must be dehydrated in order to bind directly to the RNA. These energetic costs of ion displacement and dehydration must be balanced with large favorable energetic terms from electrostatic attraction to the RNA site and, presumably, formation of cation–RNA ligand interactions.1 They have also shown that, for thermodynamic measurements (and therefore other techniques that measure the stability of folded RNA structures) of tRNA, properties attributed to localized, specific ion interactions may in fact arise from a class of ions that are weakly and nonspecifically bound.1,2 This situation complicates the prospect of linking the occupation of cation sites to RNA function and even provokes the question as to whether such well-defined sites exist in solution.

The structural studies presented here confirm that the HHRz A9/G10.1 metal ion site is indeed a well-defined site that is occupied under solution conditions even in a competing background of high Na+ concentration. To compensate for energetic penalties, sites in RNA that favor chelated metal ions might be expected to have a high local negative electrostatic potential as well as well-placed ligands. Both properties are present in this HHRz metal site. These results suggest that the N7 of G10.1 and the pro-R phosphate oxygen of A9 are positioned in a specific orientation to form a binding pocket for a metal ion to coordinate at this site. An electrostatic surface plot based on the hammerhead crystal structure also shows an area of high negative potential at the A9/G10.1 site.34 The ESEEM “water-counting” experiments confirm that the high-affinity Mn2+ ion remains quite hydrated, having four water molecules while coordinated in this pocket. The fact that the Mn2+ ion retains a high level of hydration yet has a fairly high affinity (Ka > 105 M in 1 M NaCl)20,21,25 is consistent with the general picture of a special energetic balance for ions localized in structured RNAs.

The role of the metal ion at the A9/G10.1 site of the hammerhead ribozyme on the catalytic activity is remarkable considering the nearly 20 Å distance to the cleavage site predicted by X-ray crystal structures. Modifications of this metal ion-binding site at either the guanine base or the phosphate ligand can have large effects on activity.11,15–17 A linkage between these two ligands was in fact observed in functional studies performed by Herschlag and co-workers, who found that removal of the N7 at G10.1 severely weakens the observed binding affinity for the metal ion that rescues activity with a phosphorothioate modification at A9, results that are consistent with the proposed metal binding site.15

Two main proposals have been made regarding the influence of this site on catalysis.4,15,35 The most general proposal is that metal population of this site stabilizes the correct HHRz tertiary structure. HHRz crystal structures obtained under several different ionic conditions, including solely monovalent ions, all show the ribozyme folded into a compact gamma shape. Analyses of crystals soaked in Mg2+, Mn2+, and Cd2+ ions predict several populated metal ion-binding sites including positions at A9/G10.1, at G5, and near the scissile phosphate.12,13 Although in the crystal structures the hammerhead is fully folded, regardless of the presence of divalent ions, in solution the tertiary form of the ribozyme depends on the ionic conditions. Pardi and co-workers, using analysis of residual dipolar couplings, have demonstrated that, in a solution containing 0.1 M Na+, the hammerhead is in an extended conformation with the stems fully separated.36 Lilley and co-workers, based on FRET and 19F NMR experiments, also predict that in the absence of Mg2+ the hammerhead ribozyme is in an extended conformation and that it undergoes a two-step folding transition to a more compact structure upon the addition of Mg2+ ions.37–39 The first folding transition occurs within domain II upon the addition of ≤500 µM Mg2+, reflecting the influence of an apparently high-affinity Mg2+ interaction, whereas the second folding transition of domain I occurs with the addition of 1–25 mM Mg2+ ions.38

The metal interaction responsible for the first stage of HHRz folding might be associated with the A9/G10.1 site based on this and other spectroscopic work. Pardi and co-workers observed a large Mg2+-dependent 31P chemical shift change that predicted a high affinity Mg2+ site with an apparent Kd of ~100 µM. Using specific 17O labeling, they were able to identify the shifted residue as the G13 phosphate.40 Since G13 is in domain II, this Mg2+ site is consistent with the one predicted by FRET and 19F NMR spectroscopy.37–39 Here, the highest affinity site for Mn2+ is definitively shown to include coordination to G10.1, with a Kd of ~<10 µM. A 10-fold higher affinity for Mn2+ over Mg2+ is consistent with measurements on nucleotide model compounds41 and also follows a trend observed in hammerhead activity studies.42 Thus, it is possible that the site identified here is the same as the Mg2+ site identified by 31P NMR. The coordinated A9 phosphate resonance was not observed in those studies, but the large upfield 31P chemical shift at the G13 phosphate upon metal ion population of A9/G10.1 may be consistent with stabilization of a locally rearranged structure, as also detected by 19F NMR studies.39

In addition to an apparent link to folding, it has also been hypothesized that the A9/G10.1 metal ion is directly involved in catalyzing the cleavage of the phosphodiester bond at the ribozyme active site. Herschlag and co-workers have proposed that only a single Cd2+ ion is needed to rescue catalytic activity in HHRz samples containing simultaneous Rp phosphorothioate substitutions of the A9 and the cleavage site phosphates.15 In their model, this metal ion bridges both sulfur atoms, which would be distant according to X-ray crystallography of the native ribozyme. To accommodate their proposal, an “active state” conformer is proposed to be transiently formed, in which Stems I and II effectively dock, bringing the A9/G10.1 metal ion near enough to the cleavage site to directly coordinate to the scissile phosphate group. This bridged form of the ribozyme is proposed to be an infrequently populated, active state, and the gamma shape of the HHRz observed in the crystal structures is proposed to be a “ground state” conformation of the HHRz.

In the context of this model, the coordination of the A9/G10.1 metal ion as determined here is consistent with the ion coordinated in the “ground state” conformation of the HHRz.13,18 The Mn2+ ion at this site remains highly hydrated with four water molecules and two ligands from the RNA. In order for the Mn2+ ion at the A9/G10.1 site to directly interact with a ligand from the cleavage site, the following would have to occur: the rearrangement of the hammerhead core to bring the A9 and C17 phosphates into close proximity,18 including the displacement of metal ions in the core and near the cleavage site from electrostatic repulsion,1 and the dehydration of the metal ion to open a coordination site for the scissile phosphate. The final coordination environment of the A9/G10.1 metal ion would have a more distorted geometry than that observed for the ion in the ground state, with three RNA ligands and three water molecules. Thus, adopting the “docked” conformation would have significant energetic penalties, consistent with an energetic barrier and with a lower population of the conformer in solution, as predicted by Herschlag and co-workers. Recent cross-linking studies also predict that the HHRz visits a conformation with a highly rearranged core structure.43

In line with this picture, it has recently been shown that extension of the HHRz to include interacting loops on Stems I and II results in a ribozyme that is active in much lower concentrations of Mg2+.44–47 The interacting loops may promote docking of Stems I and II, stabilizing an HHRz conformation that is closer to its active form. Thiophosphate interference studies47 indicate that, even in this context, the A9/G10.1 site is still populated and important for activity. Consistent with this, it has recently been shown that a high-affinity Mn2+ binding site with similar 14N ESEEM spectra is present in an extended HHRz sequence.48 A very recent X-ray crystal structure of an extended HHRz sequence has been reported that indeed shows the predicted docked conformation and a much closer approach of ~5 Å between the A9- and cleavage-site phosphodiester groups. No divalent cations were localized in that structure.52

The A9/G10.1 metal ion tunes activity but is not the only metal ion that influences catalysis in the truncated HHRz. In 1 M NaCl, the HHRz requires millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ or Mn2+ for activity. Since the A9/G10.1 site is occupied in very low Mg2+ concentrations, this means that other Mg2+–RNA interactions are critical in addition to this very high affinity one.4,46,49–51 The nature of these other interactions, and whether they include “site-bound” ions, is not yet known. The spectroscopic studies presented here demonstrate that the A9/G10.1 metal ion site is discretely populated with a defined geometry, even in 1 M NaCl. By analogy with protein-based metalloenzymes, these data support the tuning of HHRz catalysis by a coordinated metal ion cofactor.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for support from the NIH (GM58096 to V.J.D. and BM61211 to R.D.B.) and the NSF Chemistry Division (CHE0111696 to V.J.D. and CHE0092010 for support of TAMU EPR facilities).

References

- 1.Draper DE. RNA. 2004;10:335–343. doi: 10.1261/rna.5205404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Misra VK, Shiman R, Draper DE. Biopolymers. 2003;69:118–136. doi: 10.1002/bip.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Draper DE, Grilley D, Soto AM. Annu. ReV. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodson SA. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeRose VJ. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pyle AM. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:679–690. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedor MJ, Williamson JR. Nat. ReV. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeRose VJ, Burns S, Kim N-K, Vogt M. In: Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II. McCleverty J, Meyer TJ, editors. Oxford: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 787–813. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefan LR, Zhang R, Levitan AG, Hendrix DK, Brenner SE, Holbrook SR. Nuc. Acids Res. 2006;34:D131–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj058. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein DJ, Moore PB, Steitz TA. RNA. 2004;10:1366–1379. doi: 10.1261/rna.7390804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das R, Travers KJ, Bai Y, Herschlag D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8272–8273. doi: 10.1021/ja051422h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blount KF, Uhlenbeck OC. Annu. ReV. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:415–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.122004.184428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reviewed in Wedekind JE, McKay DB. Ann. ReV. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1998;27:475–502. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.475.

- 13.a Scott WG, Murray JB, Arnold JRP, Stoddard BL, Klug A. Science. 1996;274:2065–2069. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murray JB, Terwey DB, Maloney L, Karpeisky A, Usman N, Beigelman L, Scott WB. Cell. 1998;92:665–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pley HW, Flaherty KM, McKay DB. Nature (London) 1994;372:68–74. doi: 10.1038/372068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Karbstein K, Peracchi A, Beigelman L, Herschlag D. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14363–14378. doi: 10.1021/bi9913202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peracchi A, Beigelman L, Scott EC, Uhlenbech OC, Herschlag D. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26822–26826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peracchi A, Beigelman L, Usman N, Herschlag D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:11522–11527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray JB, Scott WG. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:33–41. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danchin A, Guéron M. Eur. J. Biochem. 1970;16:532–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horton TE, Clardy DR, DeRose V. J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:18094–18101. doi: 10.1021/bi981425p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrissey SR, Horton TE, DeRose VJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3473–3481. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrissey SR, Horton TE, Grant CV, Hoogstraten CG, Britt RD, DeRose VJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9215–9218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoogstraten CG, Grant CV, Horton TE, DeRose VJ, Britt RD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:834–842. doi: 10.1021/ja0112238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoogstraten CG, Britt RD. RNA. 2002;8:252–260. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202014826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiemann O, Fritscher J, Kisseleva N, Sigurdsson ST, Prisner TF. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:1057–1065. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturgeon BE, Britt RD. ReV. Sci. Instrum. 1992;63:2189–2192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kevan L. In: Time Domain Electron Spin Resonance. Kevan L, Schwartz RN, editors. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1979. pp. 279–341. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mims WB, Peisach J. Biol. Magn. Reson. 1981;3:213–263. [Google Scholar]

- 29.a McCracken J, Peisach J, Dooley DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:4064–4072. [Google Scholar]; b Peisach J, Davis JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:2704–2706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mims WB, Davis JL, Peisach J. J. Magn. Reson. 1990;86:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogt M. Ph.D. Dissertation. Texas A&M University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Although the assignment of these data to a directly coordinated Mn–guanine ligand is based solidly on comparison with model compounds and isotopic substitution, the interpretation of the 14N ESEEM data is complicated by the high-spin nature of the Mn(II) spin system. Previous publications (refs 22, 23) have described this 14N ESEEM pattern, observed for a purine ligand coordinated to Mn2+, as being near to the “exact cancellation” limit for 14N. In this limit, |A(14N)| ≈ 2νN(14N) and the lowest three FT peaks in the three-pulse ESEEM experiment represent quadrupolar frequencies ν0,+,−, with the property that ν0 + ν− = ν+. A higher frequency “double quantum” peak occurring at νdq = 2[(νN + A/2)2 + K2(3 + η2)]½ is also expected, where K is related to the quadrupolar coupling constant e2qQ as K= e2qQ/4. At the observing magnetic field of 3600 G, νN(14N) = 1.1 MHz. As previously described, assuming exact cancellation conditions and that the signal arises from the Ms = +½, −½ sublevels of the Mn2+ S = 5/2 spin manifold, and assigning features at 0.6, 1.9, and 2.5 MHz to ν0, ν−, and ν+, respectively, and the feature at 5.2 MHz to νdq, gives estimated values of Aiso(14N)~ 2.3 MHz and e2qQ~2.9 MHz. Hoogstraten and co-workers used ESE-ENDOR spectroscopy to directly measure A(15N) in a Mn2+–GMP model complex, obtaining predicted 14N values of Aiso(14N) = 3.0 MHz (Adip = 0.6 MHz). Attempts at simulating the 14N sample three-pulse ESEEM data using these values, however, did not fully reproduce features observed in the 14N ESEEM data (ref 23). Recently, Astashkin (ref 32a) and Dismukes (ref 32b) and co-workers have proposed that zero-field splitting may influence ESEEM frequencies, which would apply to the case of high-spin S = 5/2 Mn(II). Since the features of the EPR spectrum of Mn2+ site-bound to the HHRz show effects of increased zero-field splitting, this may indeed influence the predicted ESEEM frequencies.

- 32.a Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:6121–6132. [Google Scholar]; b Dasgupta J, Tyryshkin AM, Kozlov YN, Klimov VV, Dismukes GC. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5099–5111. doi: 10.1021/jp055213v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabat M, Cini R, Haromy T, Sundaralingam M. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7827–7833. doi: 10.1021/bi00347a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maderia M, Hunsicker LM, DeRose VJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12113–12120. doi: 10.1021/bi001249w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butcher SE. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bondensgaard K, Mollava ET, Pardi A. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11532–11542. doi: 10.1021/bi012167q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bassi GS, Murchie AIH, Lilley DMJ. RNA. 1996;2:756–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bassi GS, Murchie AIH, Walter F, Clegg RM, Lilley DMJ. EMBO J. 1997;16:7481–7489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammann C, Norman DG, Lilley DMJ. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:5503–5508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091097498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen MR, Simorre J-P, Hanson P, Mokler V, Bellon L, Beigelman L, Pardi A. RNA. 1999;5:1099–1104. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sigel H, Massoud SS, Corfu NA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:2958–2971. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunsicker LM, DeRose VJ. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;80:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heckman JE, Lambert D, Burke JM. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4148–4156. doi: 10.1021/bi047858b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khvorova A, Lescoute A, Westhof E, Jayasena SD. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:708–712. doi: 10.1038/nsb959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penedo JC, Wilson TJ, Jayasena SD, Khvorova A, Lilley DM. RNA. 2004;10:880–888. doi: 10.1261/rna.5268404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canny MD, Jucker FM, Kellogg E, Khvorova A, Jayasena SD, Pardi A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10848–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja046848v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne EM, Schaak JE, DeRose VJ. RNA. 2005;11:187–196. doi: 10.1261/rna.7950605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kisseleva N, Khvorova A, Westhof E, Schiemann O. RNA. 2005;11:1–6. doi: 10.1261/rna.7127105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rueda D, Wick K, McDowell SE, Walter NG. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9924–9936. doi: 10.1021/bi0347757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim NK, Murali A, DeRose VJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14134–14135. doi: 10.1021/ja0541027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hampel KJ, Burke JM. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4421–4429. doi: 10.1021/bi020659c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martick M, Scott WG. Cell. 2006;36:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]