Abstract

Field accident data from NASS/CDS in the US and CCIS in the UK are compared. The UK sample is deliberately weighted to conform to the same AIS proportions (within AIS 2 – 6) as the weighted NASS data so that crash severity distributions can be compared for various selected outcomes. Age and gender have a significant effect on the deltaV distributions and median deltaV values. These differences are documented both for overall AIS 2 - 6, 3 - 6, and 4 - 6, and also for body regions of the head, neck, chest, abdomen and upper and lower extremities. Anomalies between the two samples are profound which raises doubts about the recording of belt use in NASS and the calculation of deltaV at lower crash severities.

To optimise vehicle crash performance and to introduce effective regulations it is necessary and fundamental to have real world crash injury data of sufficient detail to describe the circumstances under which those injuries occur. That includes the type and severity of collision, restraint use, body regions injured and their individual injury severity, age, gender and other factors. It is equally fundamental that such field accident studies are so structured as to be representative of given study regions which in turn are chosen to be representative of a given state or country. Only if those samples of collisions are reasonably representative of the universe of crashes being considered can the vehicle designer and regulator logically use such data to optimise vehicle crash performance.

This rationale of course is not new. It was recognised by the United States National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in the 1970s with the establishment of the Fatal Accident Reporting System (FARS) and the National Crash Severity Study (NCSS). Both programs have continued since 1976 with NCSS evolving into the National Accident Sampling System (NASS) and now currently the National Automobile Sampling System, General Estimates System (GES) and the Crashworthiness Data System (CDS).

The last data set is the one of greatest use for detailed analysis because it comes from about 5000 crashes which are investigated annually in considerable detail. In particular estimates are made of crash severity in terms of change in velocity, together with a large number of outcome variables.

On a smaller scale a similar approach was developed in Britain, originating from detailed multidisciplinary crash investigations at the Transport Research Laboratory and the University of Birmingham in the 1970s. In 1981 the Cooperative Crash Injury Study (CCIS) began and from that time between 1000 and 1500 crashes have been investigated annually. The study areas from which cases are sampled and investigated when combined give a reasonable cross section of traffic conditions in Britain.

Elsewhere in Europe individual teams such as the Hannover Medical School, INRETS, Volvo, Peugeot-Renault and Daimler Benz, have conducted in-depth crash studies, but without any coordination or any sampling structure which gives a basis for national representation.

Three factors illustrate the increasing need for better crash investigation and injury data in Europe. First, the European Union has exclusive control over vehicle design regulation; member states having ceded that aspect of safety regulation to the EU over 20 years ago. That fact alone suggests that the European Commission should at least have some passing knowledge of the circumstances of traffic crashes on a pan-European basis. No such database exists to support and justify European Directives nor to monitor their effectiveness. Secondly, the last decade has seen many safety innovations introduced into car design, such as improved seat belts, front and side airbags and advanced structural designs mostly without regulatory control. The need to assess the benefits, limitations and side effects of such advances is increasingly clear (Mackay 2000).

Thirdly, vehicle crash performance is moving towards adaptive technology, in which protection will be tailored specifically towards the person exposed in a specific collision. Smart restraints will change their characteristics to recognise biomechanical, anthropometric and geometrical variations amongst car occupants. Fundamental to such an approach is a knowledge of how important are those factors in present day crashes.

This study compares the North American data set of NASS/CDS with the UK CCIS crash file. Its purpose is to see if those data sets are at all compatible, if systematic, fundamental differences are present, and whether for a small number of outcome variables, the results obtained are at least comparable qualitatively.

DATA SOURCES

The CCIS data used in this study was collected between the years of 1992 and 1994. The CCIS database is maintained by the Transport Research Laboratory and is sponsored by a consortium of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers and the UK Department of Environment, Transport and Regions (DETR). The database only includes passenger cars, which were less than 7 years old at the time of the crash and were towed away to a garage or a vehicle dismantler (Hassan et al. 1995, Mackay et al. 1985).

The CCIS study requires a stratified sampling criterion to be applied for the crashes to be selected for further investigation. Some 80% of serious and fatal and some 10 – 15% slight injury crashes according to the UK Government’s classification are investigated. The resulting sample is biased towards more serious injuries. Some 1500 crashes were investigated annually.

The NASS data for the years 1993 through 1996 was used for this study. The NASS database is maintained by NHTSA and is also a stratified sample of tow away crashes occurring in the United States, similarly biased towards more serious injuries. The NASS crash investigation teams perform in depth investigations on a sample of 5,000 crashes per year.

The CCIS and NASS data contain some unique factors, such as deltaV and detailed injury classification (Noga and Oppenheim 1981, AAAM 1990). DeltaV, for example, permits analysis of occupant injuries by crash severity and the detailed injury classifications permit analysis of injury severity by body region.

The following criteria were used to select the data for the study:

Vehicles: The vehicle had to be a passenger car. In the UK data there are relatively few airbag cases in which the airbags were activated. For comparability therefore all airbag deployment cases were eliminated from both samples.

Frontal collisions: Data was only collected for front impact collisions with Principal Direction of Force (PDoF) of 11 - 1 o’clock in which the restrained front seat occupant was injured. Only cars for which the collision severity (deltaV) was known were included. Thus all other crash types, lateral, rear and rollovers were excluded.

Injury: Front seat occupants had to have sustained a Maximum AIS (MAIS) of a level of 2 - 6 on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS). MAIS refers to the highest AIS injury sustained by an occupant. In this study, the AIS is also used when injury severity of individual body regions are considered.

Occupant: Only occupants older than 16 years of age of known age and gender were included.

Seat belts: For the US and the UK samples, front seat occupants wearing three point restraint systems were included.

Severity: Both studies included only tow -away crashes.

These selection criteria resulted in a sample of 181 (122 male and 59 female) passenger car occupants from the CCIS data and 592 (257 male and 335 female) passenger car occupants from the NASS data. The NASS and CCIS data were then weighted to allow for the bias in the data collection sampling plans.

NASS weighting for the NASS sampling plan is structured to be typical of the US crash experience. The NASS weighting factors therefore translate the 592 occupants to 89,536 occupants, weighted up to give a predicted number for the whole country.

The NASS weighted data was disaggregated by AIS categories giving the following ratios:

| AIS6 | AIS5 | AIS4 | AIS3 | AIS2 |

| 1 | 4.6 | 12.3 | 83.9 | 242.5 |

The CCIS unweighted data meeting the selection criteria (181 occupants) had the following AIS ratios:

| AIS6 | AIS5 | AIS4 | AIS3 | AIS2 |

| 1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 17.2 |

The unweighted CCIS data were then weighted to match the NASS data by AIS categories. The rationale for this was to obtain deliberately two matched samples by injury outcome distributions, which could then be compared in terms of the crash severity distributions for a number of subsets. This procedure was used so that sampling differences would be eliminated.

An additional reason is that although the CCIS programme calculates weighting factors for its sample of collisions, when these weighting factors are applied to the unweighted raw data using the police categories of slight, serious and fatal, the proportions of these categories are different from the proportions which are reported nationally by the police.

This is illustrated by the average ratios presented below for the years 1992 – 1994.

| RAGB | CCIS unweighted | CCIS weighted |

| 1 : 11.2 : 63.9 | 1 : 6.3 : 9.8 | 1 : 7.5 : 41.2 |

The RAGB (Road Accidents – Great Britain) data is for injured car occupants, averaged for the years 1992 – 1994, being the ratios of fatal to serious to slight casualties (HMSO 1998). It is clear that the CCIS sample even when weighted diverges significantly from the national data. Hence for the purposes of this study the CCIS data were deliberately weighted to the NASS ratios as that sampling would not distort the comparisons of the two data sets.

The data below show the various elements of the NASS and CCIS data sets. The NASS and CCIS ratios were obtained by dividing the number of occupants with a particular injury severity by the number of occupants with an injury severity of MAIS 6. The CCIS weight factors were obtained by multiplying the CCIS raw data with the quotient obtained by dividing the NASS weight ratio with the CCIS raw ratio. Applying these factors to the CCIS raw data produced the CCIS matched to these NASS weighted sample.

Elements of the NASS and CCIS data sets

| Injury Severity MAIS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database Set | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| NASS raw | 104 | 179 | 231 | 886 | 1383 |

| NASS weighted | 260 | 1204 | 3197 | 21827 | 63048 |

| NASS weight ratio* | 1 | 4.6 | 12.3 | 83.9 | 242.5 |

| CCIS raw | 6 | 13 | 13 | 46 | 103 |

| CCIS raw ratio | 1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 17.2 |

| CCIS matc hed to NASS weight | 6 | 27.2 | 72.7 | 501.2 | 1452 |

Ratio of MAIS 6 to each of the MAIS severities.

RESULTS

The analysis is only concerned with the distribution of deltaV for front seat restrained occupants receiving an injury severity of MAIS 2 - 6 when involved in a frontal impact. The analysis compares the overall distribution of injury severity of the whole body and also the overall injury severity of the individual body regions by gender and occupant age. The occupants are grouped into three categories; young (16 – 29 years), middle (30 – 59 years) and elderly (≥ 60 years).

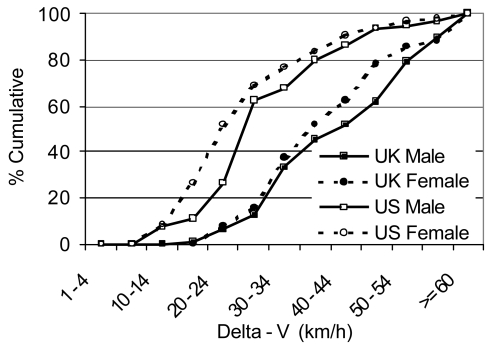

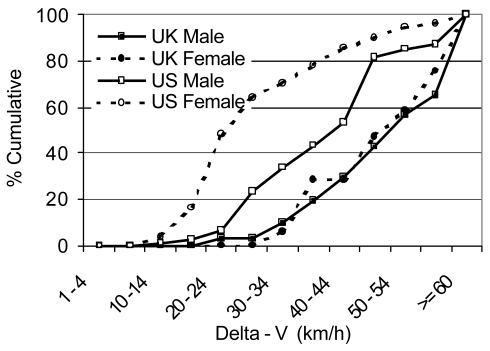

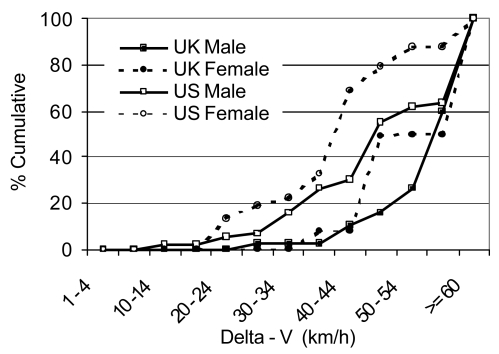

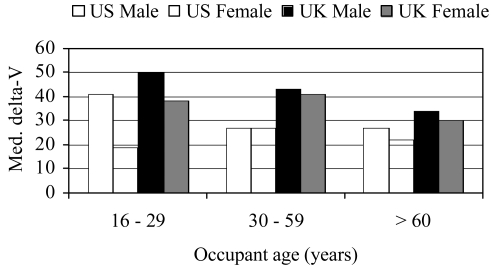

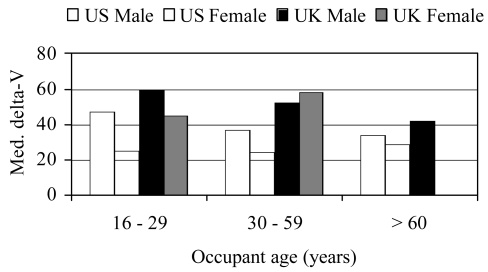

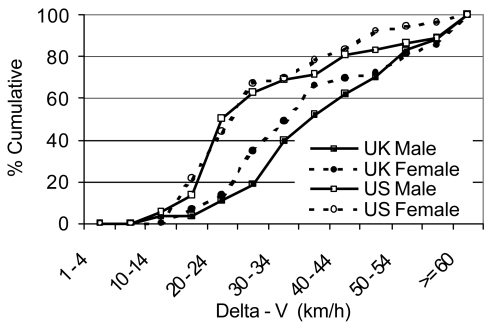

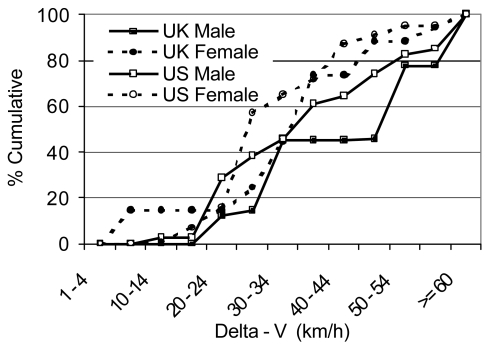

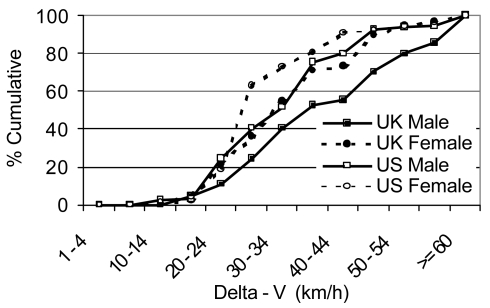

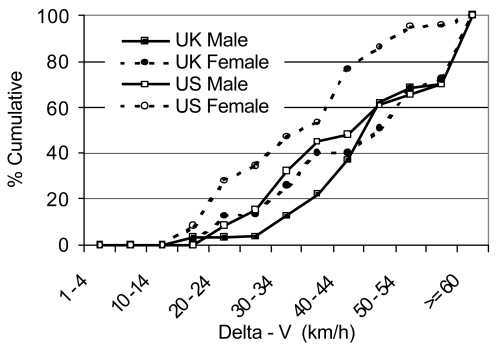

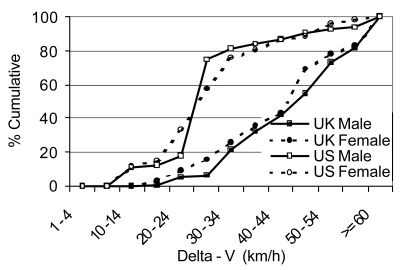

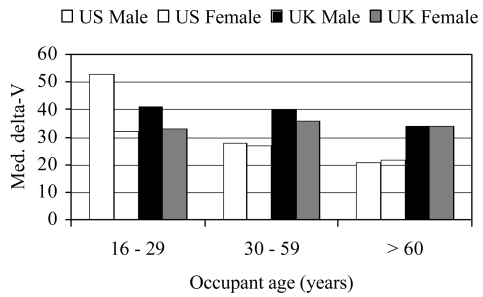

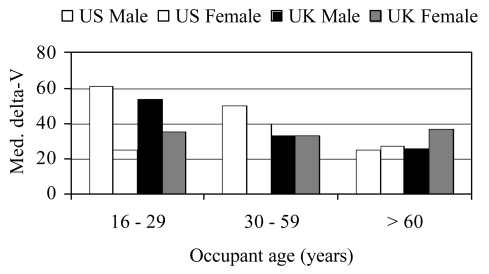

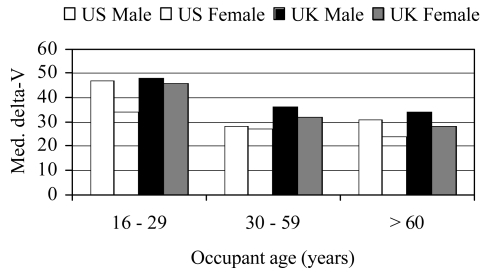

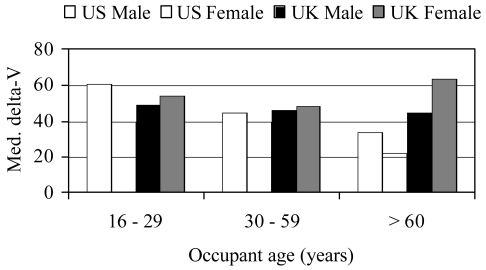

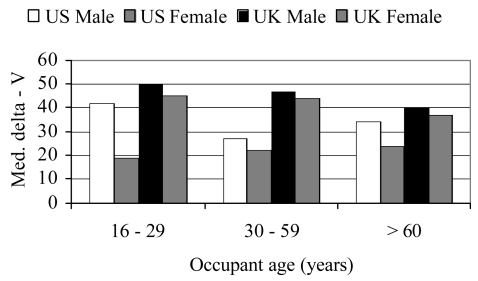

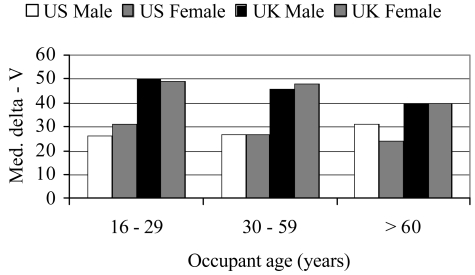

The distribution of deltaV for UK and US occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6, MAIS 3 – 6, and MAIS 4 – 6 are shown in figures 1, 3 and 5. The distributions for age, gender and median deltaV are shown in tables 2 to 4 and figures 2, 4 and 6.

Fig 1.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6.

Fig 3.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 3 – 6.

Fig 5.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 4 – 6.

Table 2.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 3 – 6.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 4324 | 47 | 2554 | 37 | 2230 | 34 | 9108 | 44 |

| UK | 2781 | 60 | 11626 | 52 | 1057 | 42 | 15490 | 52 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 5985 | 25 | 7772 | 24 | 3623 | 29 | 17380 | 25 |

| UK | 2651 | 45 | 5216 | 58 | - | - | 8870 | 51 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 4.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the head and face region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 2852 | 53 | 5220 | 28 | 4162 | 21 | 12233 | 24 |

| UK | 34616 | 41 | 34465 | 40 | 13375 | 34 | 84580 | 38 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 4819 | 32 | 5968 | 27 | 4561 | 22 | 15348 | 27 |

| UK | 21212 | 33 | 20077 | 36 | 8916 | 34 | 58046 | 35 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Fig 2.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 3 – 6.

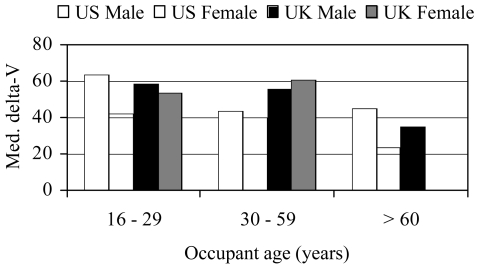

Fig 6.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 4 – 6.

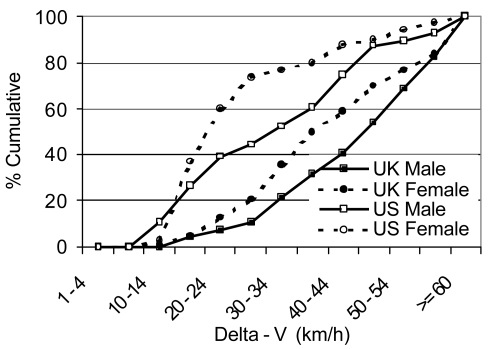

Figures 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17 show the distributions of deltaV experienced at each body region with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 to 6 for occupants experiencing an overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6. The distributions for age, gender and median delta – V for these occupants are shown in tables 5 to 10 and figures 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18. For example, Figure 7 shows the deltaV experienced by occupants with an overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6 who received an injury to the head/face region with highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6. The distributions of age, gender and median deltaV for these occupants who received a highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to head/face region is shown in table 5 and figure 8, and for other body regions in subsequent figures and tables.

Fig 7.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 - 6 to the head and face region.

Fig 9.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the neck and cervical spine region.

Fig 11.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the chest and thoracic spine region.

Fig 13.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the abdomen and lumbar spine region.

Fig 15.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the upper extremity region.

Fig 17.

Distribution of delta – V for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the lower extremity region.

Table 5.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the neck and cervical spine region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 429 | 61 | 274 | 50 | 1131 | 25 | 1834 | 35 |

| UK | 2126 | 54 | 2035 | 33 | 27 | 26 | 4689 | 54 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 1978 | 25 | 844 | 40 | 936 | 27 | 3758 | 27 |

| UK | 4913 | 35 | 4082 | 33 | 1057 | 37 | 10052 | 35 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the head and face region.

Fig 10.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the neck and cervical spine region.

Fig. 12.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the chest and thoracic spine region.

Fig. 14.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the abdomen and lumbar spine region.

Fig. 16.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the upper extremity region.

Fig. 18.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the lower extremity region.

This approach is taken so that the reader can assess directly the size of the data cells and the quality of the data sets directly.

INTERPRETATION AND DISCUSSION

Change in velocity (deltaV) has been taken as the basic parameter on which to compare the two data sets. As a measure of the crash severity it has become the preferred parameter, which can be calculated from the measurements taken from a retrospective investigation of a damaged car. Both data sets have approximately the same protocols for measuring vehicle crush and both data sets use the same CRASH algorithms. What is immediately apparent throughout all of the data in Figures 1 to 9 is a systematic difference between the US and UK results.

Given that the CCIS data have been deliberately weighted to conform to the same weighting of injury severity categories in CDS, this is a surprising result. Possible explanations are;

some undiscovered systematic difference in the calculation process for deltaV

some systematic difference in injury coding conventions.

a specific difference in calculating low values of deltaV.

Figure 1 shows for CDS that 20% of MAIS 2 plus injuries are occurring at less than 20 km/h (12 mph) whereas in the UK data that number is very close to zero. Given that this analysis is restricted to restrained front seat adult occupants, with an injury of AIS 2 or greater, it raises doubts about the reliability of the correct assessment of seat belt use in CDS. It seems intrinsically unlikely that one in five occupants, restrained in frontal crashes with an injury of AIS 2 or greater, is in a crash of less than 20 km/h (12 mph).

This fundamental difference between the two data sets limits specific comparisons. It can only be resolved by detailed case by case analysis beyond the scope of this paper. Its importance however, needs to be recognised and resolved, as these data sets are used separately in Europe and the United States as the basis for future rule-making and design decisions. It is highly unlikely that there are such gross real differences between the two countries, with for example, a mean deltaV for MAIS 2 - 6 in the US of 26 km/h against a value of 44 km/h in the UK.

It is still of interest, however, to explore within each data set separately some of the variations which arise from differences in gender, age, and different body regions and injury severity.

Figure 1 shows that for MAIS 2 plus, gender differences do not have a great effect. When age is considered something odd appears in the US data in that young females (16 - 29 years) with MAIS 2 plus are in extremely low speed collisions. A priori one expects mean deltaV to decrease with increasing age and that indeed occurs in the UK data and with US males. Given that even in the unweighted data the numbers of cases in each cell represented in Table 2 are relatively large, it suggests a particular problem either with reporting of belt use in the US or with calculation of low speed deltaV or both. This issue is illustrated clearly in Figure 3, which gives delta V histograms for MAIS 3 - 6. These data show an enormous divergence between the sexes in the US data with almost 50% of restrained females with MAIS 3 plus injuries in collisions with a deltaV less than 24 km/h (15 mph). This is highly unlikely.

One can conclude from the UK data that broadly speaking age is a more important variable than sex, particularly for the age group of 60 years and older.

Figures 5 and 6 and table 4 examine AIS 4 – 6 but here the cell sizes become so small that the results are inconclusive. One remark that can be made is that over 60% of US restrained females with AIS 4 – 6 injuries are in crashes at less than 44 km/h, (27 mph), compared to 10% in the UK. This again is unlikely.

The remaining tables present the data for AIS 2 – 6 for the main body regions, the head, neck, chest, abdomen, upper extremities and lower extremities. For the neck and upper extremities the cell sizes become so small that no conclusions should be drawn.

For the head, the thorax and the lower extremities, the UK results show consistent differences between the sexes with females having a less severe deltaV distribution than males for the same level of injury.

The age effect is important and shows lower average deltaV values for the ≥ 60 years age group, although small numbers limit the validity of that conclusion for some body regions.

The US data shows large and random variations, which suggest that low cell sizes and the question of verified seat belt use are confounding the results.

Overall however, field accident data such as is analysed here reflects experimental biomechanical studies in emphasizing age and gender differences across the population with females and the elderly being the vulnerable segments.

This study then is a cautionary tale in attempting to make international comparisons between two different data sets. The confusion in the results is itself of interest however because the data sets are used extensively to justify design decisions and rule – making. Further comparisons are needed to explore the anomalies outlined in this paper.

(Presenter: Murray Mackay)

Leonard Evans: I have published extensively, using the NASS database, on age and gender relative to fatality risk. I was focusing on fatalities from the same impact and I published relationships. I recently revisited that and find great consistency and I do have quantitative relationships which actually appear on pages 491-492 of the current Proceedings in the graphs of subdued symbols and I’ll be saying a little bit more tomorrow in the 4 minutes that has been allotted to me. And that greater risk was shown in your slides but without the quantitative thrust to them. For age I find that for each additional year we live after age 20, males are 2.5% more likely to die than they were the year before and females are 2.2% more likely to die then they were the year before. I do this by looking at a wide variety of different crash experiences including belted occupants of cars and trucks. There’s great consistency; I interpret it to be an effect at the physiological levels so I am not at all surprised that this effect is apparent in the UK and the US even if there are these other differences in determining delta V.

M. Mackay: Yes (audience laughter).

Alfred Bowles: In the United States as compared to the UK there is pressure to recover reimbursement based on diagnosis and level of treatment that is provided at the time of initial visit and such. Have you looked at whether or not the way physicians in the United States code may influence upgrading certain types of diagnoses, or perhaps overrate the size or nature of injury?

M. Mackay: It may be a factor and it would be nice to get into the actual operational detail of how the NASS cases are coded and whether there is some systematic difference. There may well be, particularly for some body regions.

Jim Pywell: You indicated that there were no airbag related investigations. Did you try to examine the effects of passive belts in the US as compared to mostly active belts in Europe in this timeframe?

M. Mackay: No, we wanted specifically to have 3 point belts because in Europe we only have 3 point belts.

J. Pywell: What about 3 point passive systems? Was any further investigation taken to understand the effect of the passive system in that timeframe?

M. Mackay: We did check in terms of 3 point passive versus 3 point active and we found no differences showing up.

Ted Miller: A very useful paper. I was wondering – in the US in this time period, belt use was probably about 65-70% in the general driving population. I wonder what the comparable number was for Britain.

M. Mackay: Higher. Ali Hassan [in the audience] can answer this directly. He in fact did most of the work on this paper.

Ali Hassan: The belt use rate in the CCIS database which is what we used for this analysis is about 90%. In the NASS database, it’s about 54%.

T. Miller: So I wonder when you do your weighting, whether you might try next time differentially weighting the belted and the unbelted so that you bring it up to comparable counts of belted and unbelted occupants.

M. Mackay: We looked at restraint use first and then weighted it up.

T. Miller: I understand. Thank you.

Ken Digges: Along those lines about five years ago, Dr. Mallieris looked at the overreporting of belt use in NASS and published a paper in the SAE recommending a reduction of about 20% of the low severity crashes. And in all of the analysis he’s done for NHTSA over the last 5 years, he rejected randomly every fifth case to develop the sample and I think NHTSA has accepted that procedure. It also truncates the weighting factors to 2500.

Table 1.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 2 – 6.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 10097 | 41 | 22270 | 27 | 9791 | 27 | 42158 | 27 |

| UK | 26016 | 50 | 71166 | 43 | 21388 | 34 | 118596 | 43 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 17277 | 19 | 19283 | 27 | 10817 | 22 | 47377 | 24 |

| UK | 15721 | 38 | 31355 | 41 | 4357 | 30 | 55340 | 39 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 3.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with overall injury severity of MAIS 4 – 6.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 1077 | 64 | 217 | 44 | 1133 | 45 | 2428 | 45 |

| UK | 275 | 59 | 599 | 56 | 54 | 35 | 956 | 56 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 785 | 42 | 890 | 40 | 558 | 24 | 2233 | 40 |

| UK | 145 | 54 | 204 | 61 | - | - | 349 | 61 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 6.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the chest and thoracic spine region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 3336 | 47 | 3854 | 28 | 8171 | 31 | 15361 | 34 |

| UK | 11986 | 48 | 35829 | 36 | 29297 | 34 | 79740 | 37 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 3517 | 34 | 8106 | 27 | 4042 | 24 | 15664 | 27 |

| UK | 4756 | 46 | 29297 | 32 | 18213 | 28 | 54748 | 32 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 7.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the abdomen and lumbar spine region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 1177 | 61 | 571 | 45 | 625 | 34 | 2373 | 45 |

| UK | 5721 | 49 | 7178 | 46 | 154 | 45 | 16960 | 46 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 1384 | 40 | 1491 | 40 | 1271 | 22 | 4146 | 38 |

| UK | 2830 | 54 | 5482 | 48 | 2008 | 64 | 11772 | 48 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 8.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the upper extremity region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 2157 | 42 | 3869 | 27 | 2212 | 34 | 8238 | 34 |

| UK | 25375 | 50 | 38156 | 47 | 4085 | 40 | 72548 | 49 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 7631 | 19 | 8905 | 22 | 2758 | 24 | 19295 | 22 |

| UK | 17228 | 45 | 15374 | 44 | 12249 | 37 | 50237 | 41 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

Table 9.

Distribution of median delta V (km/h) for restrained front seat occupants with the highest injury severity of AIS 2 – 6 to the lower extremity region.

| Data base | Age of Occupant (years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 – 29 | 30 – 59 | ≥ 60 | All* | |||||

| N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | N | dv | |

| Male | ||||||||

| US | 9806 | 26 | 15782 | 27 | 2176 | 31 | 27764 | 27 |

| UK | 34240 | 50 | 58493 | 46 | 8615 | 40 | 107307 | 47 |

| Female | ||||||||

| US | 8923 | 31 | 20136 | 27 | 4229 | 24 | 33289 | 27 |

| UK | 13532 | 49 | 21893 | 48 | 20434 | 40 | 63699 | 46 |

Includes all occupants older than 16 years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Co-operative Crash Injury Study is funded by the Department of Environment, Regions and Transport, Ford Motor Company Limited, Nissan Motor Company, Rover Group, Toyota Motor Company, Honda Motor Company and Volvo AB. The project is managed by the Transport Research Laboratory.

Grateful thanks are extended to everyone involved with the CCIS data collection process.

REFERENCES

- Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) 1990 Revision. Des Plaines, Il: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AM, Hill JR, Parkin S, Mackay M. Secondary Safety Developments : Some Applications of Field Data. Autotech’95, IMechE; London. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- H.M.S.O. The Casualty Report. HMSO; London: 1998, Road Accidents Great Britain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay M. Safer Transport in Europe : Tools for Decision Making. The European Transport Safety Lecture; E.T.S.C., Brussels, Belgium. January, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay M, Galer GD, Ashton SJ, Thomas P. The Methodology of In-Depth Studies of Car Crashes in Britain. SAE Tehcnical Paper Number 850556, Society of Automotive Engineers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Noga T, Oppenheim T. CRASH3 User’s Guide and Technical Manual. USDOT; 1981. [Google Scholar]