Abstract

Effects of Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibition were investigated in cytokinetically quiescent multiple myeloma (MM) and primary CD138+ cells. Coexposure to the Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibitors AZD7762 and selumetinib (AZD6244) robustly induced apoptosis in various MM cells and CD138+ primary samples, but spared normal CD138− and CD34+ cells. Furthermore, Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor treatment of asynchronized cells induced G0/G1 arrest and increased apoptosis in all cell-cycle phases, including G0/G1. To determine whether this regimen is active against quiescent G0/G1 MM cells, cells were cultured in low-serum medium to enrich the G0/G1 population. G0/G1–enriched cells exhibited diminished sensitivity to conventional agents (eg, Taxol and VP-16) but significantly increased susceptibility to Chk1 ± MEK1/2 inhibitors or Chk1 shRNA knock-down. These events were associated with increased γH2A.X expression/foci formation and Bim up-regulation, whereas Bim shRNA knock-down markedly attenuated lethality. Immunofluorescent analysis of G0/G1–enriched or primary MM cells demonstrated colocalization of activated caspase-3 and the quiescent (G0) marker statin, a nuclear envelope protein. Finally, Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition increased cell death in the Hoechst-positive (Hst+), low pyronin Y (PY)–staining (2N Hst+/PY−) G0 population and in sorted small side-population (SSP) MM cells. These findings provide evidence that cytokinetically quiescent MM cells are highly susceptible to simultaneous Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibition.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an accumulative disorder of mature plasma cells that is almost universally fatal. MM treatment has been revolutionized by novel agents such as immunomodulatory drugs (eg, lenalidomide) and proteasome inhibitors (eg, bortezomib). One barrier to successful MM treatment is it is a low-growth-fraction disease before the late phase supervenes and that MM cells can rest in a quiescent, nonproliferative state with < 5% of cells actively cycling.1–3 Moreover, low proliferation of tumor cells, including MM cells, may contribute to resistance to conventional or novel targeted agents.1,4,5

Cellular defenses against DNA damage are mediated by multiple checkpoints that permit cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, or, if damage is too extensive, apoptosis.6,7 Checkpoint kinases (Chk1 and Chk2) play key roles in this DNA-damage response network.8,9 In contrast to Chk2, which is inactive in the absence of DNA-damaging stimuli, Chk1 is active in unperturbed cells and is further activated by DNA damage or replicative stress.10 Chk1 activation occurs even in nonproliferating cells.11 Given its critical role in the DNA-damage response, Chk1 represents an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Previous studies have shown that pharmacologic Chk1 inhibitors abrogate cell-cycle arrest in transformed cells exposed to DNA-damaging agents, triggering inappropriate G2/M progression and death through mitotic catastrophe.12

Dysregulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK cascade in transformed cells, including MM cells,13 has prompted interest in the development of small-molecule inhibitors. Multiple agents target the dual specificity kinases MEK1/2, which sequentially phosphorylate ERK1/2, leading to activation.14 The MEK1/2 inhibitor PD184352 (CI-1040)15 has been supplanted by other MEK1/2 inhibitors with superior PK/PD profiles, such as selumetinib (AZD6244/ARRY142886).14,16 AZD6244 has shown significant in vivo activity in a MM xenograft model system,17 and trials of AZD6244 in MM are under way.

Previously, we reported that interruption of the Ras/MEK1/2 cascade by PD184352 dramatically increased the lethality of the multikinase and Chk1 inhibitor UCN-01.18–21 It is important to extend these studies to more specific Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibitors currently in clinical trials, such as AZD776222 and AZD6244. Moreover, the possibility exists that Chk1-inhibitor strategies abrogating DNA-damage checkpoints might be ineffective in cytokinetically quiescent MM cells, as is the case for more conventional therapies.1,5 The results reported herein demonstrate that regimens using AZD7762 and AZD6244 potently induce MM-cell apoptosis in all phases of the cell cycle, including G0/G1. Furthermore, this strategy selectively targets primary MM cells while sparing their normal counterparts. Our findings indicate that, in addition to cycling cells, cytokinetically quiescent (G0/G1) MM cells are highly susceptible to concomitant Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition.

Methods

Cells and reagents

The human MM cell lines NCI-H929 and U266 were purchased from ATCC. RPMI8226 cells were provided by Dr Alan Lichtenstein (University of California, Los Angeles). The IL-6–dependent MM cell lines ANBL-6 and KAS-6/1 were provided by Dr Robert Orlowski (The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). BM samples were obtained with informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki from MM patients undergoing routine diagnostic aspiration with approval from the Virginia Commonwealth University institutional review board. CD138+ and CD138− cells were isolated as described previously.19 The purity of CD138+ cells was > 90% and viability > 95%. Normal BM CD34+ cells (M-101B) were purchased from Lonza. The purity of CD34+ cells was > 95% and viability > 80% when thawed. The MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 and the selective Chk1 inhibitor AZD7762 were provided by AstraZeneca. The MEK1/2 inhibitor PD184352 and the selective Chk1 inhibitor CEP389123 were obtained from Upstate and Cephalon, respectively. In most cases, parallel studies using AZD7762 and CEP3891 (and in some cases, the prototypical Chk1 inhibitor UCN-01) in multiple MM cell lines were performed to reduce the likelihood that off-target actions of agents or cell-line–dependent responses might be responsible for the observed effects. The caspase inhibitor BOC-D-fmk was purchased from Enzyme System Products. Reagents were dissolved in sterile DMSO (final concentration < 0.1%) and stored at −80°C.

Enrichment of G0/G1 cells

MM cells enriched in the G0/G1 phase were obtained by incubating H929, 8226, and U266 in low-serum medium (0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.05% FBS, respectively)11,24 for ≥ 42 hours before cotreatment with AZD6244/AZD7762 or PD184352/CEP3891.

Assessment of apoptosis and cell death

For a discussion of our assessment of apoptosis and cell death, please see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Clonogenic assays

Colony-forming ability was evaluated using a soft agar cloning assay described previously.19

RNA interference and stable transfection

For a discussion of RNA interference and stable transfection, please see supplemental Methods.

Western blot analysis

Samples were prepared from whole-cell pellets. Proteins (20 μg) were separated on precast SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen) and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were probed with primary Abs: anti-Bim (Calbiochem); anti–phospho-p44/42 (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-MAPK (ERK1/2) and anti-p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology); anti–poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (anti-PARP; Biomol); anti–caspase-3 (BD Biosciences); anti-cleaved (activated) caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology); phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139; Upstate Biotechnology); and anti-statin Ab S-44 (provided by Dr E. Wang, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY). Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were prepared using digitonin lysis buffer as described previously.20 Anti–cytochrome c (BD Pharmingen), anti-AIF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–smac/DIABLO (Upstate Biotechnology), and anti-Bax (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Abs were used to monitor the release of mitochondrial pro-apoptotic factors and Bax redistribution. Blots were reprobed with anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) or anti-tubulin Abs (Oncogene) to ensure equal loading and protein transfer.

Comet assay

Single-cell gel electrophoresis assays were performed to assess single- and double-stranded DNA breaks using a Comet Assay Kit (Trevigen) as per the manufacturer's instructions.21 Images were captured using fluorescence microscopy at 20×/0.50.

Cell-cycle analysis

Cell-cycle analysis of DNA content after drug treatment by propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) using Modfit Version LT2.0 software as described previously.25

Distribution of apoptotic cells in cell-cycle phases

Caspase-3 activation/DNA content analysis were performed by dual-parameter flow cytometry to determine apoptotic cells within specific cell-cycle phases.26 Cells were stained with a 1:100 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488 (AF 488)–conjugated anti-cleaved (activated) caspase-3 for 1 hour at 4°C. DNA was stained with PI as described in “Cell-cycle analysis.” In these studies, subdiploid (late apoptotic) cells, which cannot be related to a specific cell-cycle compartment, were gated out and not included in this analysis.

Colocalization of statin and activated caspase-3

Dual statin and activated caspase-3 expression was quantified by flow cytometry to determine apoptotic cells within statin-positive populations (G0/G1 phase).27 After being fixed in 70% cold ethanol, blocked with 5% normal goat serum, and permeabilized with 0.5% Tween 20, cells were incubated with an anti-statin mAb (S-44) or control IgG, followed by secondary AF 599–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Cells were then stained with anti-cleaved (activated) caspase-3 Ab and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescent staining

In situ coexpression of statin and activated caspase-3 or γH2A.X foci formation was performed by immunofluorescent staining.23,27 Cells fixed on slides were rehydrated, blocked with 5% normal goat serum, and permeabilized with 0.5% Tween 20. Cells were incubated with an anti-statin mAb or control IgG, followed by secondary AF 599–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG. After washing, slides were stained with either AF 488–conjugated anti-cleaved (activated) caspase-3 Ab or AF 488–conjugated anti-γH2A.X Ab (Cell Signaling Technology), respectively. Images were captured with an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope and analyzed with RS Image Version 1.7.3 software (Roper Scientific Photometrics).

Multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of G0 phase cells

Dual-parametric flow cytometry to monitor DNA and RNA content was used to identify quiescent (G0) cells using the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst; Molecular Probes) and the RNA-specific dye pyronin Y (PY; Sigma-Aldrich), respectively.28,29 To exclude G1 phase and G0 to G1 transition cells accumulating RNA,29 G0 populations displaying Hst+ and low PY uptake (Hst+/PY−) were gated as R17. To identify cells undergoing apoptosis in the Hst+/PY− (G0) population, 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) staining (0.5 μg/mL at 37°C for 30 minutes) was adapted for triparametric analysis. Hst+/PY−/7-AAD+ cells were gated as R16. Flow cytometry parameter settings were as reported previously.29 Controls for Hst/PY or 7-AAD staining alone and negative controls (without dye) were used as compensation. Fluorescence data were obtained from 30 000 cells per sample. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using Summit Version 4.0 software (Dako Cytomation).

Analysis of SSP cells

Small side-population (SSP) MM cells were isolated as described previously.30,31 In addition, gates were set for both the side population (SP) and low FSC (small size) population (designated SSP) after gating out PI-stained (dead) cells on a flow cytometer (FACSAria II; BD Biosciences), as described in supplemental Methods. The sorted SSP cells were then exposed to agents as indicated, after which apoptosis was determined by monitoring activated caspase-3 by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

For flow cytometric analyses, values represent the means ± SD for at least 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. Significance of differences between experimental variables was determined using the Student t test. Median Dose Effect analysis was performed as described previously.21

Results

Novel Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibitors synergistically promote apoptosis in IL-6–dependent and –independent MM cells

To determine whether the specific, clinically relevant Chk1 inhibitor AZD7762 and the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 interacted in MM cells, IL-6–independent H929 cells were pretreated with various AZD6244 concentrations for 24 hours, followed by exposure to AZD7762 (200 or 300nM) for another 48 hours, after which time survival was monitored using the MTT assay. Significant reductions in survival occurred with coadministration of 500nM AZD6244 and became more pronounced at higher concentrations (Figure 1A). Parallel results were obtained with annexin V staining (Figure 1B). Pretreatment with minimally toxic concentrations of AZD6244 for 24 hours significantly increased annexin V positivity induced by 48 hours of 100-600nM AZD7762 treatment (Figure 1C). Combined treatment markedly increased cell death, which was first discernible at 24 hours and the most pronounced 36-48 hours after AZD7762 addition (Figure 1D). Median dose effect analysis yielded combination index values < 1.0, indicating synergistic interactions (Figure 1E). TUNEL analysis confirmed the striking increase in apoptosis after combined treatment (Figure 1F). Moreover, coadministration of minimally toxic AZD7762 and AZD6244 concentrations sharply reduced clonogenicity (Figure 1G). Finally, AZD6244 pretreatment effectively blocked AZD7762-induced ERK1/2 activation and increased caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 1H).

Figure 1.

The MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 blocks ERK1/2 activation induced by the novel Chk1 inhibitor AZD7762 in human MM cells, leading to synergistic induction of apoptosis and diminished clonogenicity. (A) H929 cells were pretreated (24 hours) with the indicated concentrations of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244, followed by 200nM or 300nM AZD7762 for another 48 hours, after which time cell survival was monitored with the MTT assay. **P < .01 and ***P < .002 versus values for cells treated with AZD7762 alone. (B-C) H929 cells were sequentially treated as described in panel A with AZD6244 in either the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of AZD7762 (B), or with the indicated concentrations of AZD7762 in either the presence or absence of 2.5μM AZD6244 (C). After drug treatment, the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V+) cells were determined by flow cytometry. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 versus values for cells treated with AZD6244 or AZD7762 alone. (D) H929 cells were incubated for the indicated intervals with 300nM AZD7762 after preadministration (24 hours) of 2.5μM AZD6244. Cell death was then monitored by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry. *P < .01 and **P < .001 versus values for cells treated with AZD7762 alone. (E) H929 cells were treated with a range of AZD6244 concentrations for 24 hours and a range of AZD7762 concentrations for another 48 hours, alone or in combination at a fixed ratio (50:1). At the end of this period, 7-AAD+ cells were determined by flow cytometry. Median-dose effect analysis was used to characterize the nature of the interaction. Two additional studies yielded equivalent results. (F) H929 cells were treated with 2.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours ± 300nM AZD7762 for another 48 hours, and then stained on Cytospin slides by TUNEL. (G) Alternatively, after being treated with the indicated concentrations of AZD6244 for 24 hours and AZD7762 for another 48 hours, cells were washed free of drug and plated in soft agar. After incubation for 14 days, colonies, consisting of groups of > 50 cells, were scored, and colony formation for each condition was expressed relative to untreated controls. Results represent the means ± SD for 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. **P < .005 versus single-drug treatment. (H) In parallel, H929 cells were pretreated for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of AZD6244 and with 300nM AZD7762 for another 48 hours, after which time Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate ERK1/2 phosphorylation and caspase-3 cleavage. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-tubulin Ab to ensure equal loading and transfer. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

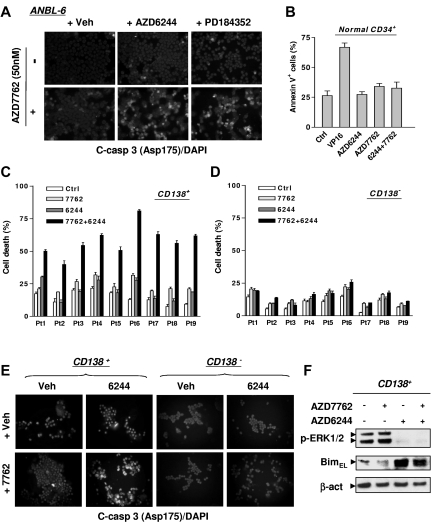

To determine whether these effects could be generalized, parallel studies were performed in multiple MM cell lines. As shown in Figure 2A, pretreatment for 24 hours with AZD6244 or another MEK1/2 inhibitor, PD184352, markedly increased caspase-3 activation induced by 48 hours of 50nM AZD7762 treatment in IL-6–dependent ANBL-6 cells. Western blot analysis revealed that MEK1/2 inhibitors blocked AZD7762-induced ERK1/2 activation, while increasing PARP and caspase-3 cleavage (supplemental Figure 1A). Similar interactions occurred in multiple other MM cell lines, including IL-6–dependent KAS-6/1 cells (supplemental Figure 1B) and IL-6–independent RPMI8226 and U266 cells (supplemental Figure 1C-D).

Figure 2.

The AZD7762/AZD6244 regimen induces apoptosis in IL-6–dependent MM cells and selectively targets primary CD138+ MM cells while sparing their normal hematopoietic counterparts. (A) IL-6–dependent ANBL-6 cells were exposed to 2.5μM AZD6244 or 2.5μM PD184352 for 24 hours, followed by 50nM AZD7762 for another 48 hours, after which time cells were immunofluorescently stained with AF 488–conjugated Ab directed against cleaved (activated) caspase-3 to monitor caspase-3 activation. Images were captured microscopically at 40×/0.65. (B) Normal cord blood CD34+ cells were exposed to 5μM AZD6244 ± 300nM AZD7762 or 4μM VP-16 for 24 hours, after which time the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V+) cells was determined by flow cytometry. (C-D) Primary CD138+ MM cells (C) and their CD138− counterparts (D) were isolated from the BM samples of 9 patients with MM. Cell death responses of cells exposed for 24 hours to 250nM AZD7762 ± 5μM AZD6244 were examined by trypan blue exclusion. (E) Once the number of CD138+ cells was suitable, followed by drug treatment as described in panels C and D, primary cells were immunofluorescently stained with AF 488–conjugated cleaved (activated) caspase-3 Ab to confirm apoptosis. The representative images shown were captured microscopically at 40×/0.65. (F) Primary CD138+ MM cells from a MM patient were treated as described in panel C, and then subjected to Western blot analysis to monitor ERK1/2 phosphorylation and Bim expression. Lanes were loaded with 10 μg of protein; blots were reprobed with Abs to β-actin to ensure equivalent loading and transfer.

AZD6244 selectively increases AZD7762 lethality in primary CD138+ MM cells

Selectivity of the AZD7762/AZD6244 regimen was examined. AZD7762 ± AZD6244 exerted minimal toxicity toward normal CD34+ cells (Figure 2B). Primary CD138+ MM cells isolated from BM samples of 9 unselected MM patients were exposed for 24 hours to AZD7762 ± AZD6244, after which time cell death was monitored. For each sample, individual drug treatment induced minimal to modest lethality, whereas combined treatment substantially increased cell death (Figure 2C). Combined treatment induced minimal lethality in CD138− BM cells (Figure 2D). A representative sample stained for fluorescently labeled activated caspase-3 highlights the pronounced killing of primary CD138+ MM cells while sparing their CD138− counterparts (Figure 2E). Western blot analysis revealed that AZD7762 induced ERK1/2 activation in primary CD138+ MM cells, an effect abrogated by AZD6244 and accompanied by BimEL up-regulation (Figure 2F), as observed in cultured MM cell lines.20 Similar phenomena were also observed with another specific Chk1 inhibitor, CEP389123 (data not shown).

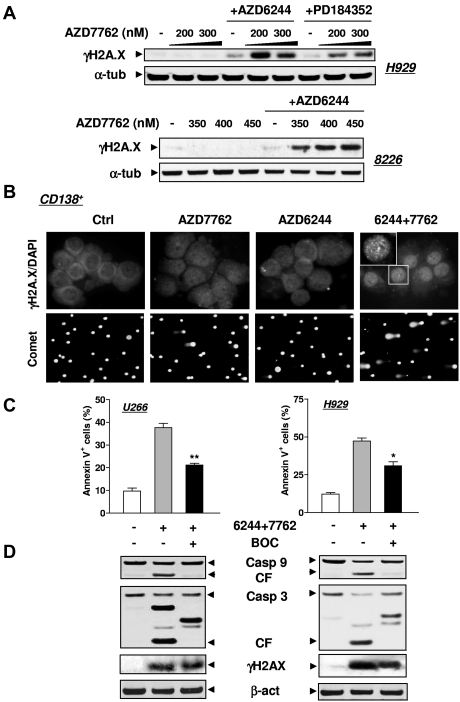

MEK1/2 inhibitors promote DNA damage induced by Chk1 inhibitors in both MM cell lines and primary CD138+ MM cells

Whereas exposure of MM cell lines (eg, H929 or RPMI8226) to AZD7762 or AZD6244 individually had minimal effects, combined treatment robustly increased the expression of γH2A.X (Figure 3A), a double-strand DNA damage marker.23 Coexposure of primary CD138+ MM cells to AZD7762/AZD6244 clearly increased DNA damage, manifested by increased γH2A.X nuclear foci (Figure 3B top panels) and a comet assay (Figure 3B bottom panels). Similar results were obtained in primary CD138+ cells exposed to CEP3891 and PD184352 (data not shown). The pan-caspase inhibitor BOC-fmk attenuated MM cell apoptosis but not γH2A.X expression (Figure 3C-D), arguing against the possibility that DNA damage resulted from apoptosis.

Figure 3.

MEK1/2 inhibitors enhance DNA damage induced by AZD7762 in MM cell lines and primary CD138+ MM cells. (A) H929 and RPMI8226 cells were exposed to either AZD6244 (H929, 2.5μM; 8226, 5μM) or PD184352 (5μM for both lines) for 24 hours followed by the indicated concentrations of AZD7762 (H929, 24 hours; 8226, 32 hours). Cells were then lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis to assess γH2A.X (phosphorylated H2A.X at Ser139) expression. (B) Primary CD138+ MM cells isolated from the BM sample of a patient with MM were incubated with 250nM AZD7762 in the presence or absence of 5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours, and then immunofluorescently stained with AF 488–conjugated phospho-H2A.X (Ser139) Ab. Images were captured microscopically at 60×/1.40 under oil (top panels). In parallel, a comet assay was performed to assess DNA breaks (bottom panels), as described in “Methods.” (C) U266 and H929 cells were sequentially treated with 2.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by AZD7762 (U266, 100nM; H929, 300nM) for 28 hours in the presence or absence of 20μM BOC-D-fmk. After treatment, the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V+) cells was determined by flow cytometry and was significantly lower (*P < .05 and **P < .02) than the values for cells treated with AZD6244/AZD7762 in the absence of BOC-D-fmk. (D) Alternatively, cells treated as described in panel C were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated primary Abs. For panels A and D, each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-tubulin or anti-actin Ab to ensure equal loading and transfer. Two additional studies yielded equivalent results.

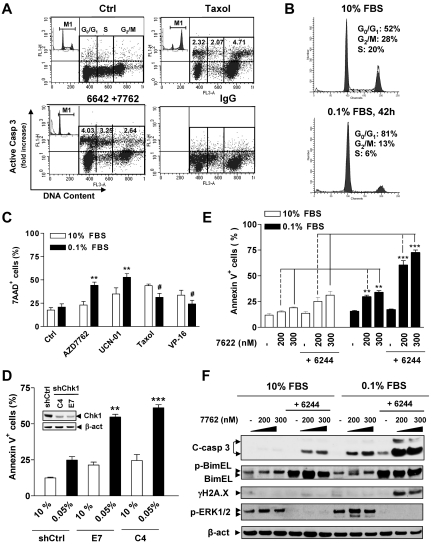

Cotargeting Chk1 and MEK1/2 results in G0/G1 arrest of MM cells and increased apoptosis in all phases of the cell cycle, including G0/G1

To elucidate effects of this regimen on the cell cycle, flow cytometry was performed in H929 cells exposed to AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by AZD7762 for an additional 24 hours, before the induction of extensive apoptosis (Figure 1D). AZD6244 or AZD7762 alone modestly increased the G0/G1 population (Table 1). However, combined treatment significantly increased the G0/G1 population by > 80% (P < .01). Similar results were obtained in other MM cell lines such as 8226 (Table 1) and U266 (data not shown), indicating that Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition arrests MM cells in G0/G1.

Table 1.

Cell-cycle distribution of MM cells after being exposed to AZD7762 ± AZD6244 for 24 hours

| G0G1 | S | G2M | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H929 | |||

| Ctrl | 56.6 ± 2.6 | 18.6 ± 1.4 | 21.2 ± 1.9 |

| AZD7762 (200nM) | 65.0 ± 2.0 | 13.3 ± 0.6* | 18.0 ± 1.4 |

| AZD7762 (300nM) | 66.8 ± 1.7 | 13.0 ± 0.4* | 21.2 ± 1.7 |

| AZD6244 (1.5μM) | 63.4 ± 1.5 | 19.3 ± 0.7 | 19.0 ± 0.8 |

| 6244 + 7762 (200nM) | 81.3 ± 1.3† | 9.1 ± 0.5† | 10.1 ± 1.0† |

| 6244 + 7762 (300nM) | 80.5 ± 1.3† | 9.5 ± 0.5† | 10.9 ± 1.2† |

| 8226 | |||

| Ctrl | 58.5 ± 2.0 | 29.1 ± 2.2 | 12.6 ± 1.0 |

| AZD6244 (3μM) | 71.0 ± 2.7* | 17.5 ± 2.0 | 10.5 ± 1.7 |

| AZD7762 (300nM) | 61.4 ± 0.7 | 26.7 ± 1.2 | 12.0 ± 0.5 |

| 6244 + 7762 | 79.6 ± 1.2† | 11.7 ± 1.02* | 7.7 ± 0.8 |

Values represent the means ± SD of triplicate determinations.

*P < .05 and †P < .01 = significantly greater or less than values for untreated cells.

To examine effects of cell-cycle distribution on responses to Chk1/MEK1 inhibition, dual-parameter flow cytometric analysis of cleaved (activated) caspase-3 and cell cycle (PI staining for DNA content) in 8226 cells was performed to monitor caspase-3 activation specifically in each cell-cycle phase after gating out subdiploid cells.26 As shown in Figure 4A, treatment with the microtubule-stabilizing agent Taxol resulted in a 4.7-fold increase over values for untreated cells in caspase 3 activation in G2/M cells, clearly greater than that observed in G0/G1-phase (2.3-fold) and S-phase (2.0-fold) cells (Figure 4A), documenting the reliability of this approach. AZD7762/AZD6244 increased caspase-3 activation within all phases of the cell cycle (eg, 4.0-, 3.3-, and 2.6-fold increases in G0/G1, S, and G2M phase, respectively; Figure 4A). These findings argue that the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimen targets MM cells in each phase of the cell cycle, including G0/G1.

Figure 4.

The Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor strategy kills MM cells in G0/G1 phase. (A) RPMI8226 cells cultured in 10% FBS were sequentially exposed to 1.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by 400nM AD7762 for another 24 hours or 5nM Taxol as a control. The distribution of apoptotic cells in various cell-cycle phases was then determined by flow cytometry combining staining for cleaved (activated) caspase-3 (y-axis) and DNA content (PI; x-axis). The representative results are shown to indicate caspase-3 activation in specific populations of cell-cycle phases, including G0/G1, S, and G2M. Values indicate the -fold increases (treated vs untreated control) of cells displaying caspase-3 activation within each phase of the cell cycle after gating out the subdiploid population. Inset shows the corresponding results of cell-cycle analysis. Taxol-treated cells were incubated with IgG instead of anti-cleaved caspase-3 Ab to demonstrate the specificity of the immunostaining. (B) H929 cells were cultured in low- or high-serum–containing medium (0.1% vs 10% FBS) for 42 hours, and cell-cycle profiles were analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) After being cultured in 0.1% or 10% FBS medium for 42 hours, H929 cells were exposed to various agents, including the Chk1 inhibitors AZD7762 (300nM) and UCN-01 (150nM), the microtubulin-stabilizing agent Taxol (5nM), and the topoisomerase inhibitor VP-16 (4μM) for 24 hours. Cell death was then assessed by 7-AAD staining and flow cytometry and was significantly greater than (**P < .01) or less than (#P < .02) values for cells cultured in 10% FBS. (D) U226 cells were stably transfected with constructs encoding shRNA against human Chk1 (shChk1) or scramble control shRNA (shCtrl) and clones selected with G418. Western blot analysis demonstrates down-regulation of Chk1 expression in 2 shChk1 clones (C4 and E7) compared with shCtrl cells (inset). Cells were then cultured in medium containing 0.05% or 10% FBS for 48 hours, after which time the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V+) cells was determined by flow cytometry and was significantly greater (**P < .02 and ***P < .01) than values for cells cultured in 10% FBS. (E) H929 cells were cultured in 0.1% FBS for 26 hours, and then treated with 1.5μM AZD6244 for 18 hours, followed by the indicated concentrations of AZD7762 for another 24 hours. The extent of apoptosis was analyzed by annexin V staining and flow cytometry and was significantly greater (**P < .005 and ***P < .001) than values for cells cultured in 10% FBS. (F) Alternatively, cells were subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated primary Abs.

G0/G1–enriched MM cells display increased susceptibility to the AZD7762/AZD6244 regimen

The preceding findings indicated that the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimen arrested cultured MM cells in G0/G1, induced apoptosis in the G0/G1 population, and was active toward primary CD138+ MM cells. To validate whether, in addition to cycling MM cells, this regimen might also be active against their cytokinetically quiescent counterparts, H929 cells were cultured in the presence of 10% versus 0.1% FBS, the latter to halt cell proliferation and to enrich the G0/G1 population.11,24,32 Cells maintained in 0.1% FBS medium exhibited essentially no growth compared with those cultured in 10% FBS medium (supplemental Figure 2A), with > 80% of cells accumulating in G0/G1 (Figure 4B), but there were modest differences in cell viability (Figure 4C; P > .05). Interestingly, G0/G1–enriched cells were significantly more sensitive to Chk1 inhibitors (eg, AZD7762 or UCN-01) compared with controls cultured in 10% FBS medium (Figure 4C; P < .01). However, these cells were relatively more resistant to Taxol or VP-16 (Figure 4C; P < .02 in each case), arguing against the possibility that serum-deprived cells were generically more sensitive to cytotoxic agents. Effects on caspase-3 and PARP cleavage were concordant (supplemental Figure 2B). Flow cytometric analysis also demonstrated a clear increase in the subdiploid (sub-G1) fraction in G0/G1–enriched cells after treatment with the Chk1 inhibitors compared with 10% FBS controls (supplemental Figure 2C). Moreover, G0/G1 enrichment also significantly sensitized cells to Chk1 shRNA knock-down (Figure 4D and supplemental Figure 2D), which was accompanied by increased γH2A.X expression (supplemental Figure 2E), arguing for a specific role for Chk1 inhibition in Chk1 inhibitor lethality in quiescent MM cells. G0/G1–enriched cells displayed greater susceptibility to AZD6244/AZD7762 even when these agents were administered for shorter intervals (ie, 24 hours after AZD7762 addition) than those cultured under full-serum conditions (Figure 4E; P < .005 vs 10% FBS controls). AZD6244 exposure resulted in BimEL up-regulation under both conditions, which was associated with inhibition of basal and AZD7762-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. However, G0/G1–enriched cells exposed to AZD7762/AZD6244 displayed more pronounced γH2A.X expression and caspase-3 cleavage compared with 10% FBS controls (Figure 4F). Similar results were obtained in other MM cell lines (eg, U266 cells) and in cells exposed to an alternative Chk1/MEK inhibitor regimen (eg, CEP3891/PD184352; data not shown).

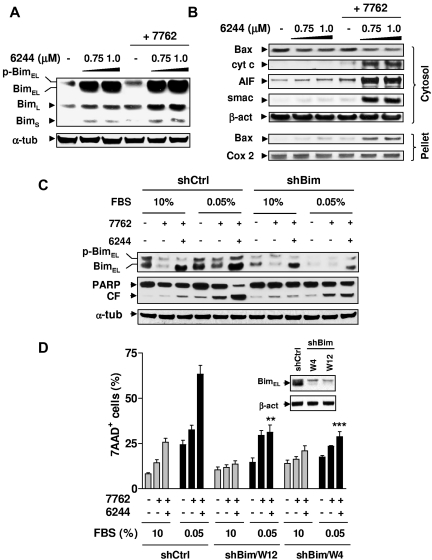

Bim plays a functional role in the pronounced susceptibility of G0/G1–enriched MM cells to Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition

As shown in Figure 5, the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 prevented Bim phosphorylation (particularly the BimEL isoform) in H929 cells exposed to AZD7762, leading to Bim accumulation (Figure 5A), Bax translocation, and the release of mitochondrial apoptotic proteins (ie, cytochrome c, smac/DIABLO, and AIF; Figure 5B). Similar results were observed in other MM cell lines (eg, RPMI8226 and U266; data not shown). To determine whether Bim up-regulation also contributed to the susceptibility of cytokinetically quiescent MM cells to the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimen, U266 cells stably transfected with Bim shRNA were used. As shown in Figure 5C, coadministration of AZD6244 with AZD7762 markedly increased BimEL expression in G0/G1–enriched U266 cells transfected with negative control shRNA (shCtrl), whereas this event was clearly attenuated in G0/G1–enriched Bim shRNA cells. shRNA knock-down of Bim (2 clones, W12 and W4) significantly diminished the ability of AZD6244 to potentiate AZD7762 lethality compared with shCtrl cells (P < .002 in each case; Figure 5C-D). Similar results were obtained in other MM cell lines (eg, RPMI8226) transfected with Bim shRNA (data not shown). These results indicate that Bim up-regulation plays an important functional role in the susceptibility of G0/G1–enriched MM cells to the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimen.

Figure 5.

Bim plays a functional role in the lethality of Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition toward G0/G1–enriched MM cells. (A) H929 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by 300nM AZD7762 for an additional 24 hours, after which time Western blot analysis was performed to monitor the expression of Bim, including phosphorylated (slow migrating) and unphosphorylated (fast migrating) BimEL, as well as BimL and BimS isoforms. (B) Alternatively, cytosolic and mitochondria-enriched (pellet) extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis to monitor the release of mitochondrial proapoptotic proteins (ie, cytochrome c, AIF, and Smac) and translocation of Bax. Parallel blots probed for Cox-2 (cytochrome oxidase subunit 2, a protein of mitochondrial inner membrane) and β-actin are shown to ensure equal loading and transfer for mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively. (C) Bim shRNA (shBim, clone W12) and scramble control shRNA (shCtrl) U266 cells were cultured in medium containing 0.05% or 10% FBS for 48 hours, followed by coadministration of 1.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours ± 300nM AZD7762 for an additional 48 hours. Western blot analysis was performed to monitor BimEL expression and PARP degradation. CF indicates the cleavage fragment. (D) shBim (clones W12 and W4) and shCtrl U226 cells were treated as described in panel C, after which time the percentage of dead (7-AAD+) cells was determined by flow cytometry and was significantly less (**P < .01 and ***P < .002) than values for shCtrl cells treated identically in 0.05% FBS medium. Inset shows Western blots demonstrating knock-down of Bim in shBim cell, compared with shCtrl cells. For panels A through D (inset), each lane was loaded with 20 μg of protein; blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-actin Ab to ensure equal loading and transfer. Two additional studies yielded equivalent results.

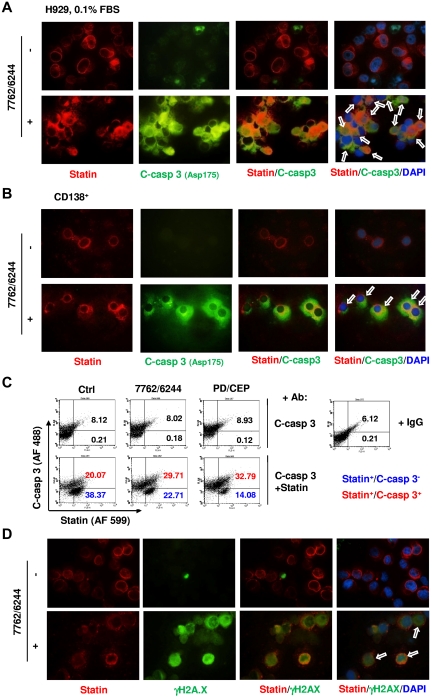

Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition induces apoptosis in MM cell lines and primary CD138+ cells expressing the G0 marker statin

Statin is a 57-kDa nuclear envelope protein primarily expressed in cytokinetically quiescent G0 cells and rapidly down-regulated during progression to the G1 phase.27,33 Western blot analysis revealed that G0/G1–enriched H929 cells exhibited a marked increase in statin expression (supplemental Figure 3A), and immunofluorescent staining demonstrated a marked increase in statin-positive cells after G0/G1 enrichment by culturing in 0.1% FBS (supplemental Figure 3B). Primary CD138+ MM cells clearly expressed statin (supplemental Figure 3C), which is consistent with their quiescent status.1–3

Untreated G0/G1–enriched H929 cells displayed robust red fluorescence (statin) but little green fluorescence (activated caspase-3; Figure 6A). AZD7762/AZD6244-treated cells displayed clear colocalization of statin and activated caspase-3. Parallel studies in primary CD138+ MM cells revealed that AZD7762/AZD6244 exposure resulted in pronounced caspase-3 activation in statin-positive cells compared with untreated cells (Figure 6B). These findings were supported by parallel studies involving alternative Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitors (eg, CEP3891 and PD184352; supplemental Figure 3D-E). Colocalization of statin/activated caspase-3 in G0/G1–enriched H929 cells was further confirmed by dual-parameter flow cytometric analysis, which indicated increased caspase-3 activation in statin-positive cells after brief exposure (12 hours after addition of Chk1 inhibitors) to AZD6244/AZAD7762 and to CEP3891/PD184352 (Figure 6C). Finally, dual-immunofluorescent staining revealed that γH2A.X expression (green fluorescence) colocalized with statin expression (red fluorescence) in AZD6244/AZD7762–treated G0/G1–enriched H929 cells at an early interval (6 hours after AZD7762) (Figure 6D). Parallel results were also obtained with CEP3891/PD184352 (supplemental Figure 4). These findings support the notion that cytokinetically quiescent MM cells are sensitive to DNA damage and apoptosis induced by this regimen.

Figure 6.

Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition induces caspase-3 activation and γH2A.X expression in statin-positive (G0/G1) MM cells. (A) H929 cells were incubated in 0.1% FBS medium for 64 hours, and then exposed to 1.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by 300nM AZD7762 for an additional 18 hours. (B) Primary CD138+ MM cells isolated from the BM sample of a patient with MM were exposed to 5μM AZD6244 and 250nM AZD7762 for 24 hours. For panels A and B, cells were immunofluorescently stained with Abs against statin (red fluorescence) and cleaved (activated) caspase-3 (green fluorescence) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) after treatment. Images were captured microscopically at 60×/1.40 under oil and then merged as indicated. Arrows indicate cells exhibiting colocalization of statin and activated caspase-3 expression. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments. (C) H929 cells enriched for G0/G1 as described in panel A were exposed to MEK1/2 inhibitors (1.5μM AZD6244 or 1.5μM PD184352) for 24 hours, followed by Chk1 inhibitors (300nM AZD7762 or 300nM CEP3891 for an additional 12 hours. Flow cytometric analysis was used to quantify the percentage of cells coexpressing statin and activated caspase-3 (upper right quadrant). In parallel, untreated cells were incubated with IgG instead of statin or cleaved caspase-3 Abs as a negative control to demonstrate the specificity of the immunostaining. Numbers indicate the percentage of activated caspase-3–negative (blue) or –positive (red) in the statin+ population. Two additional studies yielded equivalent results. (D) Alternatively, G0/G1–enriched H929 cells were treated 1.5μM AZD6244 for 24 hours, followed by 300nM AZD7762 for an additional 6 hours, immunofluorescently stained with Abs against statin (red fluorescence) and γH2A.X (green fluorescence), and then counterstained with DAPI (blue). Images were captured microscopically at 60×/1.40 under oil and then merged as indicated. Arrows indicate cells coexhibiting statin and γH2A.X expression/foci formation.

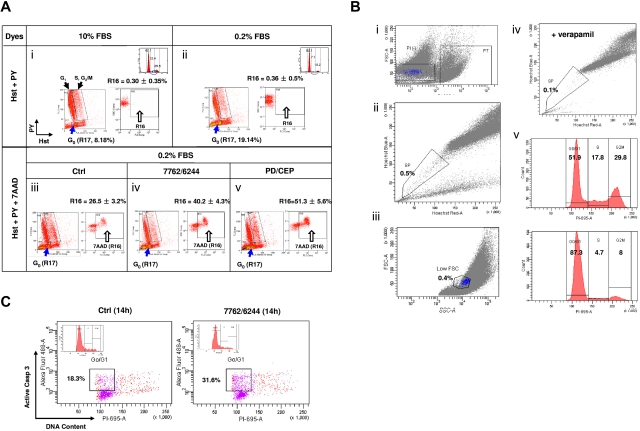

Hst +/PY− G0 MM cells are susceptible to the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimen

To confirm that Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition kills cytokinetically quiescent (G0) MM cells, a multiparameter flow cytometric analysis was used. This method is specifically designed to identify G0 cells displaying Hoechst positivity (Hst+, corresponding to 2N diploid cells) but low pyronin Y uptake (PY−, because of lack of RNA synthesis) from other populations, particularly G1 (Hst+/PY+).28,29 As shown in Figure 7A panels i and ii, RPMI8226 cells cultured in 0.2% FBS medium displayed an enriched Hst+/PY− (G0) population (gate R17), compared with 10% FBS controls (19.14% vs 8.18% of the bulk population). 7-AAD staining was then incorporated to monitor cell death (R16) in the Hst+/PY− (R17 gated-in) population. After 12 hours of treatment with AZD7762/AZD6244, the Hst+/PY− population exhibited a clear increase in 7-AAD uptake over untreated controls (Figure 7A panels iii and iv; R16, 40.2% vs 26.5%; P < .01). Significant increases in cell death of Hst+/PY− cells (51.3%) also occurred after CEP3891/PD184352 coexposure (Figure 7A panel v; P < .005 vs. untreated controls), providing further evidence that quiescent (G0), noncycling MM cells are susceptible to Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor–mediated lethality.

Figure 7.

Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimens induce cell death in G0 MM cells characterized by the Hst+/PY− phenotype. (A) RPMI8226 cells were incubated in 0.2% or 10% FBS medium for 72 hours, after which time flow cytometry was performed to assess G0 populations by double staining DNA with Hst and RNA with PY. The G0 population (2N DNA/low levels of RNA, Hst+/PY−) was discriminated from the G1 population (2N DNA/high levels of RNA, Hst+/PY+), whereas the S and G2/M populations displayed > 2N DNA. G0 cells (R17) were gated-in for further analysis. Compared with those cultured in 10% FBS (i), flow cytometric profiles indicate enrichment of G0 population in cells cultured in 0.2% FBS (ii). In parallel, PI staining and flow cytometry were performed to monitor cell-cycle distribution (inset). Values indicate the percentage of cells in each phase. G0/G1–enriched 8226 cells were then exposed to MEK1/2 inhibitors (1.5μM AZD6244 or 1.5μM PD184352) for 24 hours, followed by Chk1 inhibitors (400nM AZD7762 or 500nM CEP3891) for an additional 12 hours. Flow cytometric analysis was performed to assess cell death (7-AAD positivity, R16) in the G0 (Hst+/PY−, R17 gate-in) population (iii-v). To ensure specificity of this assay, control experiments were performed in parallel, including negative controls (without fluorescent dye), individual staining with each dye, and double staining with each pair of dyes. Results are representative of 3 separate sets of experiments. (B) H929 cells cultured in 10% FBS medium reached a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL, after which time viable SSP cells were sorted by exclusion of Hst staining of MM cells, as described in supplemental Methods. In brief, cells were incubated with Hst and then stained with PI. For flow cytometric analysis, after gating out PI+ dead cells (i), gates were set for both the SP (ii) and low FSC (small size) population (iii). In parallel, cells were coincubated with 50μM verapamil (iv), which blocks Hst efflux, as a control. The cell-cycle profile was determined by PI staining immediately after sorting (v top, unsorted cells; v bottom, sorted SSP cells). (C) Sorted SSP cells in 5% FBS medium were then treated with the AZD6244/AZD7762 regimen for 14 hours and stained with activated caspase-3 plus PI to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells within the G0/G1 population. Two additional experiments yield roughly identical results.

Quiescent SSP MM cells are sensitive to Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor lethality

Finally, the effects of Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition were investigated prospectively in SSP MM cells, representing quiescent cells in which the presumed stem cell compartment resides.30,31 SP cells were sorted from H929 cells cultured in 10% serum (Figure 7B), as described previously.30 SP cells represented a small fraction of cells (0.5% of PI− living cells) excluding Hst (Figure 7B panels i and ii), which was further sorted for SSP cells (Figure 7B panel iii), which have been shown to represent a quiescent population.34 As a control, coincubation of verapamil substantially reduced the SP population (Figure 7B panel iv).31 Approximately 90% of sorted SSP cells resided in G0/G1 (Figure 7B panel v). Fourteen hours of treatment with AZD7762/AZD6244 resulted in a marked increase in caspase-3 activation in the G0/G1 population of the sorted SSP cells compared with untreated controls (Figure 7C). Equivalent results were obtained with the sorted SSP population of RPMI8226 cells (data not shown). These findings provide further evidence that Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition is active against quiescent MM cells.

Discussion

The preceding findings demonstrate that cytokinetically quiescent (G0/G1) MM cell lines, as well as primary CD138+ myeloma cells expressing quiescent (G0/G1) markers, are fully susceptible to strategies simultaneously targeting Chk1 and MEK1/2. It should be emphasized that G0/G1 MM cells are not selectively killed by Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition, because cells in other phases of the cell cycle are also vulnerable. However, cytokinetically quiescent cells are generally resistant to standard cytotoxic agents, particularly those targeting specific phases (eg, S and M phases) of the cell cycle.1,4,5 The finding that Chk1/MEK1/2–inhibitory regimens (eg, AZD7762/AZD6244 and CEP3891/PD184352) are active against quiescent cells may have particular significance for MM, generally a low-proliferative neoplasm.

Normally, cells respond to genotoxic insults through the coordinated actions of various cell-cycle checkpoints and DNA-repair pathways. The former include biochemical signaling pathways that monitor DNA damage and trigger cell-cycle arrest and DNA repair if the damage is repairable, or induce apoptosis or senescence if it is not.6,7 Transformed cells in general are susceptible to DNA damage and oncogene-mediated DNA-replication stress.35,36 Because checkpoints are characteristically defective in neoplastic cells,12,22,36 checkpoint abrogators have become the focus of intense interest. Chk1 is a distal signal transducer that is activated by ATM/ATR after DNA damage8 and that has been implicated in the G2/M, intra-S, and mitotic spindle checkpoints.37 More recently, Chk1 has been shown to play a more direct role in cell survival- and DNA repair–related processes.10,38,39 In this context, it has been reported that exposure to Chk1 inhibitors (eg, UCN-01 and CEP3891) or Chk1 shRNA knock-down is sufficient to induce DNA damage, even in the absence of exogenous genotoxic insults.23 The initial development of Chk1 inhibitors focused on the multikinase inhibitor UCN-01, but because of its unfavorable pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles,40 interest has shifted to more specific second-generation Chk1 inhibitors such as AZD7762, CEP3891, XL-844, and PF-477736, among many others.37 Chk1 inhibitors dramatically enhance genotoxic agent lethality by disrupting the G2/M checkpoint (in the case of DNA-damaging agents such as camptothecin and SN-38) or the intra-S phase checkpoints (in the case of DNA synthesis inhibitors such as gemcitabine).12,39,41 In these settings, cells with DNA damage progress inappropriately through the G2/M or S phase, triggering cell death. Implicit in these mechanistic models is the presumption that cell-cycle progression must occur for such disruptions to be lethal. Consequently, few attempts have been made to apply this approach to disorders involving low-proliferative malignancies, such as MM, or to cytokinetically quiescent (G0/G1) tumor cells, a characteristic of cancer stem (initiating) cells. Studies by our group have shown that interruption of the MEK1/2/ERK1/2 pathway strikingly increases UCN-01 lethality in MM cells.19–21 However, the cell-cycle relatedness of this interaction, in contrast to strategies combining Chk1 inhibitors with DNA-damaging agents, has not yet been defined nor have these findings been extended to include newer-generation, more specific Chk1 and MEK1/2 inhibitors currently under clinical evaluation. To minimize—although not completely exclude—the possible contribution of off-target effects, parallel studies were performed using 2 unrelated specific Chk1 inhibitors (AZD7762 and CEP3891) in combination with 2 MEK1/2 inhibitors (AZD6244 and PD184352).

The bulk of evidence indicates that lethality stemming from simultaneous interruption of Chk1 and MEK1/2 occurs independently of cell-cycle progression in MM cells, which, at least at early stages of the disease, display low proliferative indices and largely reside (> 95%) in G0/G1.1 This evidence includes the findings that: (1) Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimens (eg, AZD7762/AZD6244 and CEP3891/PD184352) were highly active against primary CD138+ MM cells, which have a low proliferative capacity1–3; (2) in contrast to regimens incorporating Chk1 inhibitors and genotoxic agents, which lead to inappropriate progression through G2/M,12 Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition arrested asynchronized MM cells cultured in 10% FBS medium in G0/G1 (notably, the G0/G1 population was as or more sensitive to these regimens than their cycling S or G2/M counterparts); (3) Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition induced pronounced cell death in G0/G1–enriched MM cells, whereas these cells were relatively less sensitive to VP-16 or Taxol; (4) the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimens induced cell death in cultured and primary MM cells characterized by quiescent G0 phase phenotypes (eg, statin+, Hst+/PYlow)29,33; and (5) these regimens were active against the sorted quiescent SSP population of MM cells. These observations suggest that the mechanisms through which combined Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibition induces cell death differ from those responsible for the potentiation of genotoxic agent lethality by Chk1 inhibitors, and that the former are operative in both cycling and quiescent tumor cells. In this context, very recent studies have shown that targeting the SP population of MM cells represents an important mechanism contributing to the anti-MM activity of lenalidomide.31 It will be interesting to determine whether Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimens act against this population through similar or different mechanisms.

The Ras/Raf/MEK1/2/ERK1/2 pathway plays an important role in cell-cycle progression. For example, ERK1/2 activation is required for progression from the G1 to S phase or through G2/M.42 Moreover, recent findings suggest a functional role for MEK1/2/ERK1/2 in cell-cycle checkpoints.43,44 However, the MEK1/2/ERK1/2 pathway also mediates multiple survival functions, including down-regulation of proapoptotic proteins such as Bad and Bim.45 The latter protein, implicated in potentiation of Chk1 inhibitor lethality by inhibitors of the Ras/MEK1/2/ERK1/2 pathway in the bulk population of MM cells,20 also plays a functional role in the lethality of these regimens toward quiescent (G0/G1) MM cells. In this context, the Ras pathway has been linked to checkpoint activation in quiescent cells.32 Therefore, whereas the lethal consequences of combined exposure to DNA-damaging agents and Chk1 inhibitors have been attributed to inappropriate cell-cycle progression, coadministration of MEK1/2 inhibitors may act coordinately with Chk1 inhibitors to promote genotoxicity in both cycling and quiescent cells. The ability of Chk1 inhibitors (eg, UCN-01 and CEP3891) and Chk1 knockdown by shRNA to induce DNA damage has been well documented.23 Interestingly, results of one study suggest that nonproliferating ovarian cancer cells are particularly sensitive to the lethal consequences of Chk1 inhibition.4 These findings raise the possibility that intact Chk1 function is required even in quiescent cells to circumvent the lethal consequences of spontaneously occurring DNA damage. In this context, emerging evidence indicates that, in addition to its classic checkpoint function, Chk1 plays diverse roles, including those related to survival and DNA repair.10,11,39 For example, Chk1 has been implicated in the latter through interactions with the DNA-repair machinery.39,46 Conversely, ERK1/2 activation is also involved in DNA repair through regulation of DNA-repair proteins.47 Interestingly, the type of DNA repair is cell-cycle phase dependent; that is, in quiescent (G0/G1) cells, it primarily proceeds via nonhomologous end-joining, whereas in cycling cells (S and G2/M), homologous recombination predominates.48 Therefore, it is possible that disruption of Chk1 function, particularly in conjunction with disruption of MEK1/2/ERK1/2–related DNA-repair events,47,49 may increase the susceptibility of quiescent (G0/G1) cells to DNA damage. The pronounced induction of DNA damage (eg, γH2A.X expression/foci formation) by the Chk1/MEK1/2 inhibitor regimens in G0/G1–enriched cells and in the G0/G1–labeled population supports this notion. Although a more direct role for Chk1 in homologous recombination has been recognized recently,50 evidence specifically relating Chk1 to nonhomologous end-joining or other processes characteristic of G0/G1 cells is not yet available. Further studies will be required to define the mechanism(s), such as disruption of DNA repair, that renders quiescent (G0/G1) cells vulnerable to this strategy.

In summary, the present findings provide evidence that the Chk1/MEK1/2–inhibitory strategy, in addition to killing cycling cells, is also active against cytokinetically quiescent (G0/G1) MM cells while exerting relatively minimal toxicity toward normal cells. Our findings also indicate that the mechanism(s) responsible for inducing cell death in cytokinetically quiescent (noncycling) transformed cells by this regimen may differ fundamentally from those involved in the potentiation of genotoxic agent lethality in cycling cells by DNA-damage checkpoint abrogation. For example, the present results suggest that cytokinetically quiescent transformed cells, which characteristically exhibit resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic agents,3–5 may be particularly susceptible to intrinsic DNA damage, possibly reflecting the essential function of Chk1 in the maintenance of genomic stability.39 In this setting, Bim could serve as a death trigger to promote the elimination of cells containing damaged DNA. Dysregulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, which is one of the most common aberrations in cancer, including MM,13,14 might therefore act to down-regulate Bim, allowing such cells to survive. Conversely, by up-regulating Bim, interruption of MEK/ERK signaling could lower the threshold for apoptosis in transformed cells, including those in a nonproliferative, quiescent state. The finding that Bim up-regulation is required for Chk1/MEK1/2–inhibitor lethality in G0/G1–arrested cells supports this notion. Based on in vitro and in vivo evidence of activity of AZD6244 in MM models,17 a phase 2 trial of AZD6244 in refractory MM has been initiated. Such a study could provide a foundation for successor trials combining AZD6244 and Chk1 inhibitors such as AZD7762 in MM, which would determine the in vivo relevance of the present findings more definitively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Eugenia Wang (University of Louisville, Louisville, KY) for her generous gift of the anti-statin mAb; AstraZeneca for supplying AZD7762 and AZD6244; Cephalon for supplying CEP3891; and Dr Daniel H. Conrad and Ms Julie Farnsworth (Flow Cytometry Share Resource of Virginia Commonwealth University/Massey Cancer Center, Richmond, VA) for their technical assistance in flow cytometry, which was supported in part by Massey Cancer Center core National Institutes of Health grant P30 CA16059.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA93738, CA100866, P50 CA130805-01, P50 CA142509-01, and RC2 CA148431-01), the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of America (grant R6181-10), the V Foundation, and by the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: X-Y.P. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; L.E.Y., S.C., W.W.B., Y.T., J.F., J.A.A., and L.B.K. performed the research; P.D. helped design the research; and Y.D. and S.G. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Steven Grant, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Virginia Commonwealth University Health Sciences Center, Rm 234 Goodwin Research Bldg, 401 College St, Richmond, VA 23298; e-mail: stgrant@vcu.edu.

References

- 1.Drewinko B, Alexanian R, Boyer H, Barlogie B, Rubinow SI. The growth fraction of human myeloma cells. Blood. 1981;57(2):333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar SV, Fonseca R, Dewald GW, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities correlate with the plasma cell labeling index and extent of bone marrow involvement in myeloma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;113(1):73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):175–187. doi: 10.1038/nrc746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondoh E, Mori S, Yamaguchi K, et al. Targeting slow-proliferating ovarian cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(10):2448–2456. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimanche-Boitrel MT, Pelletier H, Genne P, et al. Confluence-dependent resistance in human colon cancer cells: role of reduced drug accumulation and low intrinsic chemosensitivity of resting cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;50(5):677–682. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartek J, Lukas J. DNA damage checkpoints: from initiation to recovery or adaptation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(2):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432(7015):316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niida H, Nakanishi M. DNA damage checkpoints in mammals. Mutagenesis. 2006;21(1):3–9. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gei063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulsen RD, Cimprich KA. The ATR pathway: fine-tuning the fork. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(7):953–966. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(5):421–429. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marini F, Nardo T, Giannattasio M, et al. DNA nucleotide excision repair-dependent signaling to checkpoint activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(46):17325–17330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605446103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel C, Hager C, Bastians H. Mechanisms of mitotic cell death induced by chemotherapy-mediated G2 checkpoint abrogation. Cancer Res. 2007;67(1):339–345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(22):3291–3310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen LF, Sebolt-Leopold J, Meyer MB. CI-1040 (PD184352), a targeted signal transduction inhibitor of MEK (MAPKK). Semin Oncol. 2003;30(5 suppl 16):105–116. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA, et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1576–1583. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai YT, Fulciniti M, Hideshima T, et al. Targeting MEK induces myeloma cell cytotoxicity and inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Blood. 2007;110(5):1656–1663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Dai Y, Yu C, Singh V, et al. Pharmacological inhibitors of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase/MAPK cascade interact synergistically with UCN-01 to induce mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5106–5115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai Y, Landowski TH, Rosen ST, Dent P, Grant S. Combined treatment with the checkpoint abrogator UCN-01 and MEK1/2 inhibitors potently induces apoptosis in drug-sensitive and -resistant myeloma cells through an IL-6-independent mechanism. Blood. 2002;100(9):3333–3343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pei XY, Dai Y, Tenorio S, et al. MEK1/2 inhibitors potentiate UCN-01 lethality in human multiple myeloma cells through a Bim-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2007;110(6):2092–2101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y, Chen S, Pei XY, et al. Interruption of the Ras/MEK/ERK signaling cascade enhances Chk1 inhibitor-induced DNA damage in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2008;112(6):2439–2449. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zabludoff SD, Deng C, Grondine MR, et al. AZD7762, a novel checkpoint kinase inhibitor, drives checkpoint abrogation and potentiates DNA-targeted therapies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(9):2955–2966. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syljuåsen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, et al. Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(9):3553–3562. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3553-3562.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318(5858):1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai Y, Chen S, Venditti CA, et al. Vorinostat synergistically potentiates MK-0457 lethality in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells sensitive and resistant to imatinib mesylate. Blood. 2008;112(3):793–804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham NA, Jacobberger JW, Schimmer AD, et al. The dietary isothiocyanate sulforaphane targets pathways of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and oxidative stress in human pancreatic cancer cells and inhibits tumor growth in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(10):1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellicciari C, Mangiarotti R, Bottone MG, Danova M, Wang E. Identification of resting cells by dual-parameter flow cytometry of statin expression and DNA content. Cytometry. 1995;21(4):329–337. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990210404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen H, Boyer M, Cheng T. Flow cytometry-based cell cycle measurement of mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;430(II):77–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-182-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladd AC, Pyatt R, Gothot A, et al. Orderly process of sequential cytokine stimulation is required for activation and maximal proliferation of primitive human bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells residing in G0. Blood. 1997;90(2):658–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodell MA, McKinney-Freeman S, Camargo FD. Isolation and characterization of side population cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:343–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakubikova J, Adamia S, Kost-Alimova M, et al. Lenalidomide targets clonogenic side population in multiple myeloma: pathophysiologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2011;117(17):4409–4419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-267344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fikaris AJ, Lewis AE, Abulaiti A, Tsygankova OM, Meinkoth JL. Ras triggers ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated and Rad-3-related activation and apoptosis through sustained mitogenic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(46):34759–34767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang E. Rapid disappearance of statin, a nonproliferating and senescent cell-specific protein, upon reentering the process of cell cycling. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(5 Pt 1):1695–1701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusuf I, Kharas MG, Chen J, et al. KLF4 is a FOXO target gene that suppresses B cell proliferation. Int Immunol. 2008;20(5):671–681. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136(5):823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray AW. Creative blocks: cell-cycle checkpoints and feedback controls. Nature. 1992;359(6396):599–604. doi: 10.1038/359599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai Y, Grant S. New insights into checkpoint kinase 1 in the DNA damage response signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):376–383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niida H, Katsuno Y, Banerjee B, Hande MP, Nakanishi M. Specific role of Chk1 phosphorylations in cell survival and checkpoint activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(7):2572–2581. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01611-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enders GH. Expanded roles for Chk1 in genome maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17749–17752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuse E, Tanii H, Takai K, et al. Altered pharmacokinetics of a novel anticancer drug, UCN-01, caused by specific high affinity binding to alpha1-acid glycoprotein in humans. Cancer Res. 1999;59(5):1054–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews DJ, Yakes FM, Chen J, et al. Pharmacological abrogation of S-phase checkpoint enhances the anti-tumor activity of gemcitabine in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(1):104–110. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Yan S, Zhou T, Terada Y, Erikson RL. The MAP kinase pathway is required for entry into mitosis and cell survival. Oncogene. 2004;23(3):763–776. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung EJ, Brown AP, Asano H, et al. In vitro and in vivo radiosensitization with AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(9):3050–3057. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mogila V, Xia F, Li WX. An intrinsic cell cycle checkpoint pathway mediated by MEK and ERK in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2006;11(4):575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewings KE, Hadfield-Moorhouse K, Wiggins CM, et al. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of BimEL promotes its rapid dissociation from Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL. EMBO J. 2007;26(12):2856–2867. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goudelock DM, Jiang K, Pereira E, Russell B, Sanchez Y. Regulatory interactions between the checkpoint kinase Chk1 and the proteins of the DNA-dependent protein kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(32):29940–29947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yacoub A, Park JS, Qiao L, Dent P, Hagan MP. MAPK dependence of DNA damage repair: ionizing radiation and the induction of expression of the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 in DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells in a MEK1/2 dependent fashion. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77(10):1067–1078. doi: 10.1080/09553000110069317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golding SE, Rosenberg E, Neill S, et al. Extracellular signal-related kinase positively regulates ataxia telangiectasia mutated, homologous recombination repair, and the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1046–1053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sørensen CS, Hansen LT, Dziegielewski J, et al. The cell-cycle checkpoint kinase Chk1 is required for mammalian homologous recombination repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(2):195–201. doi: 10.1038/ncb1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.