Summary

Endoscopy has undergone explosive technological growth in over recent years, and with the emergence of targeted imaging, its truly transformative power and impact in medicine lies just over the horizon. Today, our ability to see inside the digestive tract with medical endoscopy is headed toward exciting crossroads. The existing paradigm of making diagnostic decisions based on observing structural changes and identifying anatomical landmarks may soon be replaced by visualizing functional properties and imaging molecular expression. In this novel approach, the presence of intracellular and cell surface targets unique to disease are identified and used to predict the likelihood of mucosal transformation and response to therapy. This strategy can result in the development of new methods for early cancer detection, personalized therapy, and chemoprevention. This targeted approach will require further development of molecular probes and endoscopic instruments, and will need support from the FDA for streamlined regulatory oversight. Overall, this molecular imaging modality promises to significantly broaden the capabilities of the gastroenterologist by providing a new approach to visualize the mucosa of the digestive tract in a manner that has never been seen before.

Keywords: endoscopy, molecular imaging, targets, early detection

Introduction

Endoscopic detection of disease in the digestive tract is currently being performed using visualization and interpretation of white light images reflected from the mucosal surface in real time [1]. In the esophagus, tissue transforms from normal to malignant by passing through a sequence of histological stages that include squamous, metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma [2], shown in Fig. 1. The physician makes diagnostic decisions and determines where to biopsy tissue based on architectural appearance, including mass effect, texture variations, and color changes. While this strategy has resulted in widespread use of endoscopy to perform surveillance, stage disease, and apply therapy, the diagnostic information provided by this approach primarily comes from structural changes in the tissue, such as size, shape, and number. In the absence of these changes, biopsies may be performed in a random fashion, such as in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus and ulcerative colitis, where effectiveness is significantly limited by sampling error [3,4]. Unfortunately, this strategy alone does not take advantage of the significant wealth of undiscovered information contained within the molecular properties of tissue that can reveal details about mucosal function, when properly imaged. Over the past few decades, we have obtained a tremendous growth in knowledge about the molecular processes involved in cancer biology. It is now known that cancer results from a number and variety of molecular and cellular changes that arise from a gradual accumulation of genetic changes [5]. Thus, the ability to acquire real time data about the molecular expression of cells and tissues within the digestive tract can allow physicians to improve patient management strategies. For example, observing the molecular expression pattern of pre-malignant (dysplastic) mucosa can provide new methods for the early detection of cancer, and interval imaging of expressed targets can allow physicians to monitor the efficacy of therapy. In essence, changes in molecular expression occur well before that of structural features, thus greater knowledge at an earlier time may be the key to changing the course of disease progression.

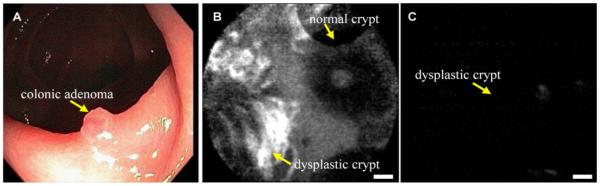

Fig 1. Cancer transformation in the digestive tract.

Progression from normal to malignant mucosa in the esophagus passes through histological stages of squamous, metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma. Molecular variations occur well in advance of morphogical changes, providing a window of opportunity to perform earlier detection and therapy.

Molecular changes in diseased cells within the mucosa can be present either inside the cell or on its surface. A significant advantage for performing targeted imaging in the mucosa of the digestive tract is the opportunity to apply exogenous probes topically. This method of administration can focus the investigation on a specific region of involvement, is much less likely to develop an immunogenic reaction, and can more easily overcome regulatory hurdles. The best studied intra-cellular targets are proteolytic enzymes and the most established cell surface targets are transmembrane proteins and glycoproteins. These structures are too small to be visualized directly, even with the highest resolution imaging instruments. Instead, exogenous probes labeled with fluorescent dyes that interact with these targets are needed to detect their presence. A number of different classes of probe technologies have been evaluated for performing targeted imaging, in both small animals and human subjects. For example, monoclonal antibodies have been investigated for tumor detection and drug delivery because of their high specificity [6,7]. However, their use in vivo has been limited by delivery challenges, immunogenicity and cost for reagent development. Recently, a number of near-infrared fluorescent imaging probes directed toward intracellular targets have been developed to detect neoplasia on fluorescence endoscopy [8]. These molecular targets include proteolytic enzymes [9], matrix metalloproteinases [10], endothelial-specific markers [11], and apoptosis reporters [12,13].

Molecular Targets

Molecular targets provide useful information about the tissue phenotype and are over expressed in transformed mucosa relative to normal. There has been great progress in unraveling the sequence of genetic changes that lead to clonal selection and growth advantages for cells in the mucosa of the digestive tract that transform into cancer [14,15]. Moreover, there is now a greater understanding of the timing of molecular changes that occur early, such as alterations in p53 and p16, versus late, such as loss of heterozygosity and cell cycle checkpoints [16,17]. This ability to acquire this information on imaging has significant implications on risk stratifying patients who have a higher likelihood for developing cancer, such as those with Barrett’s esophagus, atrophic gastritis, and ulcerative colitis. Initial efforts in developing this novel targeted endoscopic imaging strategy have focused on a number of over expressed intracellular and cell surface receptors. These targets include cathepsin B [18,19], matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [20,21], CEA [22,23], MUC1 and MUC2 [24,25], and HER2/neu (ERBB2) [26,27], and play a significant role in cancer transformation of mucosa in the digestive tract.

Proteases

Proteases are proteolytic enzymes that play an important role in cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis, and form important targets for detection and diagnosis of cancer in the digestive tract. In particular, they have been shown to be over expressed in the development of colon cancer. For example, cathepsin B has been shown to be upregulated in areas of inflammation, necrosis, angiogenesis, dysplasia, and carcinoma. In addition, metalloproteinases are believed to be targets of the Wnt signaling pathway [28]. The ability of protease-sensitive probes to improve detection of adenomas where cathepsin B is over expressed has been demonstrated in the small bowel of ApcMin/+ mice [29]. In this ex vivo study, the smallest lesion detectable was found to be 50 μm in diameter. Furthermore, the use of protease-sensitive probes to detect colonic neoplasia in vivo on wide area endoscopy has been shown using colonic tumor cells implanted into the small bowel of an animal model [30]. This combination of white light reflectance and near-infrared fluorescence images of colonic mucosa demonstrates the integration of structural and functional data using protease-activated interactions to illustrate this imaging strategy. This study showed that increased near-infrared fluorescence intensity could be used to detect over expression of cathepsin B and its related activity in neoplastic compared to normal mucosa.

Antibody Targets

The first attempts to detect cell surface targets that are over expressed in neoplastic compared to normal mucosa used monoclonal antibodies as affinity probes. Most of these targets are membrane-associated glycoproteins, and the synthesis and secretion of these high molecular weight biomolecules are common features of all glandular epithelial tissues. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a glycoprotein that is involved in cell adhesion, and is found to be increased in the serum of individuals with colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, lung and breast carcinomas [31]. The serum level of CEA typically normalizes after tumor resection, thus any subsequent elevation suggests cancer recurrence. CEA levels may also be increase in some non-neoplastic conditions, such as ulcerative colitis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Moreover, mucins, such as MUC1, are also membrane glycoproteins commonly found on epithelial cells and are anchored to the apical surface by a transmembrane domain [24]. This protein provides a protective function to the cells by binding to pathogens and also performs cell signaling. Over expression, aberrant intracellular localization, and changes in glycosylation of this protein have been associated with adenocarcinoma. MUC2 produces a secreted mucin protein that forms an insoluble mucous barrier to protect the gut lumen [25]. In patients with gastric cancer, the expression of MUC1 is associated with invasive proliferation and a poor outcome, while that of MUC2 is related with non-invasive growth and a favorable prognosis. Moreover, colorectal carcinomas show a high level of expression of fully glycosylated MUC1 in advanced stages or in metastatic lesions. In addition, the expression of sialylated MUC1 mucin is strongly correlated with poor outcome of the patients with intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma.

Peptide Targets

HER2/neu (ERBB2) is a plasma membrane receptor in the epidermal growth factor family that is normally associated with cell signaling involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and is believed to activate PI3K/Akt signaling as well [26]. This protooncogene plays an important role in promoting neoplastic progession in the esophagus by gene amplification and is associated with inhibition of apoptosis and enhanced cell proliferation [32,33]. Also, HER-2/neu signaling increases MMP activity, enhances tumorigenic and metastatic potential, and is a potent inducer of VEGF and tumor vascularity [34]. Gene amplification of HER2/neu is a common mechanism for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, and the associated gene is found to be amplified in 15 to 25% of esophageal cancers [35]. HER2/neu is also amplified in ~25 to 30% of human breast cancers, and results in the over expression of the associated receptor that is a well established target for Trastuzumab (Herceptin), a humanized monoclonal antibody [36]. In addition, small molecules, such as Lapatinib, are being developed as a novel therapy for inhibiting tyrosine kinase activity by blocking the ATP-binding site [37]. Clinical studies for treating patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma that are HER2/neu positive with Trastuzumab and Lapatinib are under way.

Molecular Probes

Intracellular and cell surface targets are typically too small in size to be visualized directly, and require the use of exogenous probes that become optically active after interacting with specific biomolecules that are over expressed in neoplastic compared to normal tissues. Probe characteristics that are promising for use in the digestive tract include 1) high diversity, 2) affinity binding, 3) rapid kinetics (time scale of minutes), 4) deep tissue penetration, 5) low immunogenicity, 6) capacity for large scale synthesis, 7) easy to label, and 8) low cost. The choice of the fluorescence label depends on the type of molecular interactions to be measured, and the wavelength of the instrument being used for excitation and emission. Visible agents, such as fluorescein derivatives, provide the best image resolution and are easy to conjugate, while near-infrared probes, provide the deepest tissue penetration and least autofluorescence background.

Proteases

Proteases are intracellular targets whose enzymatic activity creates a biochemical interaction that stimulates the molecular probe to emit light. These probes have been designed to produce near-infrared fluorescence after proteolytic cleavage, and exist in several forms, including auto-quenched, self-quenched, dual-labeled, and cell-penetrating [38]. One of the advantages of activatable probes is that a single enzyme can cleave multiple fluorophores to provide signal amplification and achieve very high target-to-background ratios. This property of activatable probes results in use of lower doses than that of non-activatable imaging probes, such as antibodies and peptides. A robust signal is critical for observing intracellular processes because the target concentration in this environment is typically quite low. Additional probe properties that require consideration include clearance, binding kinetics, degradation susceptability, and extent of non-specific accumulation. Prosense (VisEn Medical, Inc, Bedford, MA) is an intravenously injected activatable probe that consists of a synthetic graft poly-L-lysine copolymer that is sterically protected by multiple methoxypolyethylene glycol side chains and has multiple near-infrared fluorochromes [39]. A variety of proteases, in particular cathepsin B, can cleave the lysine-lysine bonds, and amplify the fluorescence signal by a factor of 15 to 30. Prosense 680 and 750 have a maximum absorption at 680 and 750 nm, respectively, and a peak emission at 700 and 780 nm, respectively. The performance of these probes has been demonstrated endoscopically in genetically engineered mice.

Antibody Targets

Antibody probes are gamma globulins that affinity bind to antigenic targets expressed on the cell surface. Light chains are basic structural units of the antibody whose tips express a wide variety of amino acid sequences that can form highly specific ionic and covalent bonds with the molecular targets. The number of different combinations of amino acid sequences defines the variability (diversity), and allows for antibodies to bind to a large number of different targets. A monoclonal mouse anti-CEA antibody has been developed to perform targeted endoscopic imaging of colonic neoplasia. The fluorescence label consists of 5(6) carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS), and has a maximum excitation and emission wavelength of 494 and 518 nm, respectively [40]. The anti-CEA antibody was labeled with FLUOS using a 1:10 molar reaction for a period of 2 hours and then was purified by gel filtration on a sephadex column to achieve a final concentration of approximately 1 mg/mL. The probe was also mixed with mucilago tylose, a gel containing methylhydroxyethylcellulose and carboxymethylcellulose, in a 4% solution to increase the viscosity of the solution prior to in vivo application. In addition, quinoline yellow was added to this mixture to form a 1% solution.

Antibodies have also been labeled with an indocyanine green (ICG) derivatives for targeting the detection of cancer in the digestive tract. ICG is a near-infrared dye that has a maximum absorption at 805 nm and a peak emission at 835 nm. It is FDA approved for intravenous use to measure cardiac output, assess hepatic function, and visualize ocular vessels. ICG derivatives including ICG-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide ester (ICG-sulfo-OSu) and 3-ICG-acyl-1,3-thiazolidine-2-thione (ICG-ATT) have been developed for labeling monoclonal antibodies [41]. Antibody probes that have been developed in this manner include anti-CEA and anti-MUC1. These compounds incur small shifts in the excitation and emission wavelengths relative to pure ICG, and have been used to demonstrate proof of principle for targeted endoscopic imaging.

Peptide Targets

Peptides have a number of advantages for performing targeted detection in the digestive tract because of their high diversity, rapid binding kinetics, and potential for deep diffusion in diseased mucosa [42]. In addition, peptides can be labeled easily, are generally non-toxic and non-immunogenic. Peptides have been selected using techniques of phage display, a powerful combinatorial method that uses recombinant DNA technology to generate a library of clones that bind preferentially to the cell surface. The protein coat of bacteriophage, such as the filamentous M13 or T7, is genetically engineered to express a high diversity (>109) of unique peptides sequences. Selection of peptides that affinity bind to over expressed cell surface targets is then performed by biopanning the library against normal and diseased cells and tissues. The DNA sequences are then recovered and used to synthesize and fluorescence label the candidate peptides. Techniques of phage display have been successfully used to identify peptides that bind preferentially to dysplastic rather than to normal mucosa in the colon and esophagus. The peptides with the highest target-to-background ratio relative to controls cells are selected for clinical use. Using this selection strategy for dysplastic esophageal mucosa, the phage with peptide sequence “ASYNYDA” was identified and found via a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search to have binding homology to protocadherin gamma [43]. Similarly, the peptide with sequence “VRPMPLQ” was selected for affinity binding to dysplastic colonic mucosa, and was found on BLAST to have binding homology to the laminin-G domain of contactin-associated protein (Caspr-1) [44].

Molecular Imaging Instruments

Wide area endoscopy

Wide area endoscopy provides high resolution images on the macroscopic scale (millimeters to centimeters) to rapidly survey large surface areas of mucosa in the digestive tract to localize regions suspicious for disease. The instrument design will depend on the fluorescence excitation and emission wavelengths of the labeled probe, and involves a tradeoff between image resolution and autofluorescence background. Visible probes, such as fluorescein derivatives require excitation and provide emission at approximately 488 nm and 510 nm, respectively. This regime provides the best image resolution but generates the most autofluorescence background. Near-infrared probes, such as ICG derivatives, provide less image resolution but generate virtually no autofluorescence background.

Proteases

For imaging of proteases using activatable probes, techniques of wide area endoscopy have been developed to collect near-infrared fluorescence images in small animal models. This microcatheter instrument consists of 10,000 collection fibers surrounded by 14 illumination fibers and is contained within a 0.8 mm diameter sheath with a working length of 100 cm [30]. The tip of the catheter is fused to an objective lens that is 0.4 mm diameter and has a 0.35 mm focal length. Fluorescence excitation is provided by a mercury vapor lamp via a 670 nm short pass filter. The light is first collimated with an aspheric lens, and delivered through a 5 mm diameter liquid light guide with numeric aperture of 0.55. The light collected by the image guide is separated by a 670 nm dichroic mirror into a white light component between 400 and 650 nm and a fluorescence emission at wavelengths longer than 670 nm which is then band pass filtered between 690 to 800 nm. Two separate collecting lens systems then relay the white light and fluorescence images onto a standard video camera and a near infrared fluorescence camera, respectively.

Antibody Targets

The endoscopic instrument for imaging cell surface targets with monoclonal antibodies uses visible fluorescence excitation that is provided by a halogen source where the light passes through a 490 nm narrow band filter [45]. The emission from the fluorescence labeled anti-CEA antibody is collected by a conventional fiber optic endoscope. This fluorescence light passes through a 520 nm narrow band filter, and the images are captured by a single reflex 35 mm camera attached to the proximal end of the endoscope. Conventional white light endoscopy is performed first, and the illumination is turned off when the fluorescein-labeled anti-CEA antibody is topically applied to the mucosal surface for an incubation time of approximately 10 min followed by rinsing of the unbound antibodies with 0.9 % saline solution.

For imaging with near-infrared fluorescence-labeled antibodies, a prototype endoscope has been developed that uses a 300 W xenon lamp as a light source [46]. The excitation band is determined by a 710 to 790 nm barrier filter placed between the lamp and the endoscope. In addition, there is an additional filter in front of the lamp to block infrared light from reaching the white light camera. Fluorescence is collected in the 810 to 920 nm band with a barrier filter placed in front of an intensified CCD camera. This detection unit, along with the white light camera, is attached to the proximal end of the endoscope with an adapter. The captured white light and fluorescence images are relayed via a control unit to an image capturing device and magneto-optical disk drive subsystem for recording and storing the images.

Peptide Targets

For imaging of peptide targets, a prototype wide area endoscope has been developed that collects fluorescence from peptides labeled with fluorescein derivatives. This instrument can image in three different modes, including white light (WL), narrow-band imaging (NBI), and fluorescence imaging [47]. In the WL mode, the full visible spectrum from 400 to 700 nm is collected, while in the NBI mode, a set of spectral bands in the red, green, and blue regimes is detected. In the fluorescence mode, a filter wheel enters the illumination path, and provides fluorescence excitation in the 395 to 475 nm band. In addition, illumination from 525 to 575 nm provides reflected light in the green spectral regime centered at 550 nm. The fluorescence image is collected by the peripherally located CCD detector that has a 490 to 625 nm band pass filter for blocking the excitation light. Normal mucosa emits bright autofluorescence, thus the composite color appears as bright green. Because the increased vasculature in neoplastic mucosa absorbs autofluorescence, it appears with decreased intensity. The WL and NBI images are collected by the center objective lens, and the fluorescence image is collected by a second objective lens located near the periphery. A xenon light source provides the illumination for all three modes, which is determined by the filter wheel located in the image processor. Illumination for all three modes of imaging is delivered through the two fiber optic light guides. Furthermore, there is 2.8 mm diameter instrument channel that can be used to deliver either a confocal microendoscope or biopsy forceps. The objectives are forward viewing and have a field of view (FOV), defined by a maximum angle of illumination of 140 deg.

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopy uses the core of an optical fiber as a pinhole, placed in between the objective lens and the detector, to allow only the light that originates from within a tiny volume below the mucosal surface to be collected [48]. All other sources of scattered light do not have the correct path to be detected, and thus become ‘spatially filtered.’ This process creates a high resolution image from a thin section within otherwise optically thick tissue, and is known as optical sectioning. Because of the sub-cellular resolution that can be achieved with this technique, it is particularly useful for validating probe binding to cells in the mucosa rather than accumulating non-specifically in mucus and debris. Moreover, the images can be collected at sufficiently fast frame rates to observe biological behavior with minimal disturbance from motion artifacts caused by peristalsis using high speed scanning mechanisms. Recent advancements in miniaturization of optics, availability of fiber-optics, and emergence of micro-scanners have allowed for the technique of confocal microscopy to be performed in vivo through medical endoscopes to perform rapid, real-time optical assessment of tissue pathology [49]. This approach represents a significant advance in endoscopic screening for the early detection of cancer by providing a new method that can increase the yield of physical biopsy, reduce the risks of screening (i.e. bleeding, infection, and perforation), and lower the cost of processing tissue pathology.

The Cellvizio (Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France) is an endoscope compatible confocal microscope that has an imaging bundle with ~30,000 optical fibers and uses a gradient index (GRIN) microlens to focus the beam [50]. There are two versions of the miniprobe, called S and HD, that have 0 or 50 μm working distance and a transverse resolution of either 5 or 2.5 μm and an axial resolution of either 15 or 20 μm, respectively. Images are collected in a horizontal plane (en face) at 12 frames per second with a field of view of either 600×500 or 240×200 μm2. Fluorescence is collected by the same optical fibers and transmitted back to the detector. A long pass filter rejects the excitation light, and fluorescence is detected with an avalanche photodiode. Image processing performed includes subtraction of fiber autofluorescence and calibration of individual fiber transmission efficiencies. The fibered confocal miniprobe has the size and flexibility to pass through the instrument channel, and to be accurately placed onto the mucosa using guidance from the white light image. The frame rate is adequate to achieve consistent images with little interference from motion artifact.

In Vivo Molecular Imaging

Proteases

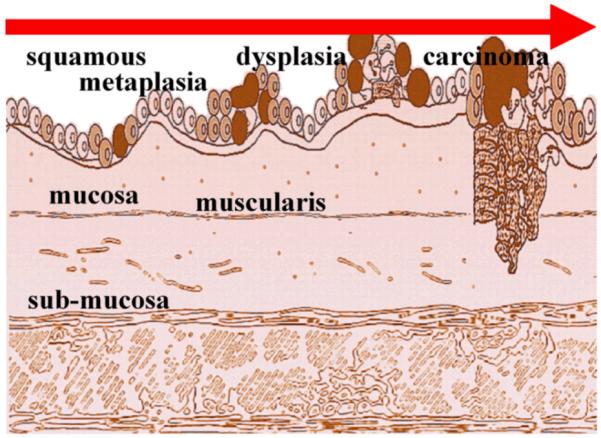

In vivo imaging of protease activity has been demonstrated in an orthotopic colon cancer model. The mucosa of the descending colon in C57BL6/J mice was injected with 1×106 CT26 murine colon cancer cells via a midline incision [30]. After 13 days to allow for tumor growth, Prosense 680, a protease-activated probe sensitive to cathepsin B, was injected intravenously at a concentration of 2 nmol in a volume of 150 μL, and small animal endoscopy was performed the next day. An increase in near-infrared fluorescence was detected at the site of the tumor, as shown in Fig. 2. Fig 2A and 2D show the in vivo white light endoscopic images of normal and cancerous murine colonic mucosa, respectively. Fig. 2B shows no fluorescence from normal mucosa, while Fig. 2E reveals a region of increased near-infrared fluorescence provided by cathepsin B activity at the site of the tumor. Fig. 2F shows a false color overlay of white light and fluorescence images to register the site of the tumor with that of the fluorescence. Combining the white light and fluorescence images integrates anatomic features from structural changes in the mucosa with functional data provided by protease activity, allowing for identification of smaller, flat lesions that may not be detected on white light endoscopy alone.

Fig 2. Near-infrared endoscopic imaging of protease activity in small animal model.

Increase in near-infrared fluorescence intensity reveals protease activity from a colonic adenocarcinoma (bottom row) in comparison to normal colonic mucosa (top row) in an orthotopically implanted mouse model. (A,D) In vivo white light endoscopic images of normal and cancerous murine colonic mucosa, respectively. (B,E) Near-infrared fluorescence images following intravenous injection of Prosense 680, a protease activated probe sensitive to cathepsin B shows increased intensity at the site of the tumor but not in normal mucosa. (C,F) False color overlay of white light with fluorescence images show integration of structural and functional data. Used with permission [30].

Antibody Targets

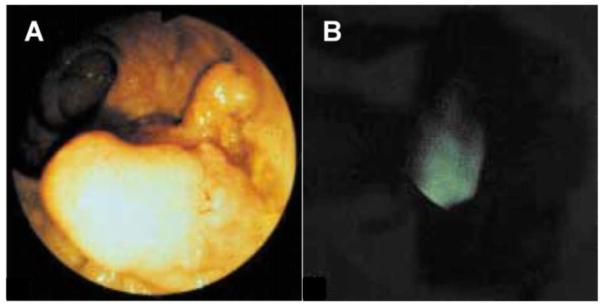

The use of topically applied fluorescence-labeled anti-CEA antibody to target the detection of dysplasia on wide area endoscopy has been demonstrated in vivo in the colon [40]. When a lesion was found on white light endoscopy, approximately 2 to 6 ml of the fluorescein-labeled anti-CEA antibody mixed with mucilago tylose was topically applied to the surrounding mucosa. An increased fluorescence signal was detected in 19 of the 25 carcinomas and in 3 of 8 adenomas. A white light endoscopic image of a colonic adenoma is shown in Fig. 3A, and reveals the presence of a mass lesion. The corresponding fluorescence image collected after topical incubation with the labeled anti-CEA antibody shown in Fig. 3B reveals increased intensity at the site of the lesion. Only 1 out of 6 adenocarcinomas that did not reveal increased fluorescence showed over expression of CEA on immunohistochemistry. The other fluorescence-negative carcinomas showed either ulceration or spontaneous bleeding without CEA reactivity in areas of tumor on immunohistochemistry. Four of the fluorescence-negative adenomas were classified histologically as low grade dysplasia. The normal appearing colonic mucosa immediately surrounding the 33 colorectal lesions did not show any significantly increased fluorescence intensity. The experimental portion of the study extended the duration of colonoscopy by approximately 15 to 30 minutes. An evaluation using the fluorescence endoscope was performed on the same specimens ex vivo immediately after resection and confirmed the in vivo results. Finally, the fluorescence intensity measured endoscopically had good correlation with CEA expression by the luminal epithelial cells on immunohistochemistry.

Fig 3. In vivo localization of anti-CEA antibody binding to colonic adenoma on fluorescence endoscopy.

(A) A conventional white light endoscopic image of a colonic adenoma reveals the presence of a mass lesion. (B) The corresponding fluorescence image collected in vivo after topical administration and incubation with the labeled anti-CEA antibody shows increased intensity at the site of the lesion. Used with permission [45].

Monoclonal ICG-sulfo-OSu-labeled mouse anti-CEA antibody has also been used to target gastric cancer on biopsy specimens and imaged with near-infrared endoscopy [41]. Immunohistochemical analysis was first performed on the excised tissues to determine which gastric specimens over express CEA. These specimens positive for CEA were rinsed with warm water containing 2000 U of Pronase, 1 gm of bicarbonate, and 4 mg of dimethylpolysiloxane for 15 minutes at room temperature. In addition, normal horse serum was administered to the specimens for 15 minutes to provide a non-specific blocking agent. The mucosal surface were then incubated with monoclonal ICG-sulfo-OSu-labeled mouse anti-CEA antibody for 60 minutes. A conventional white light endoscopic image was collected first from freshly resected gastric mucosa, and then a near-infrared fluorescence image of the same specimen stained with ICG-sulfo-OSu-labeled anti-CEA antibody was acquired, revealing foci of cancer. In addition, specimens of normal gastric mucosa did not reveal antibody binding, and was used as a control.

Peptide Targets

The use of topically applied fluorescence-labeled peptides to target the detection of high-grade dysplasia on wide area endoscopy has been demonstrated in vivo in Barrett’s esophagus [43]. With IRB approval and informed consent, patients with a history of Barrett’s esophagus and biopsy proven high-grade dysplasia scheduled for endoscopic mucosal resection were recruited into the study. Each subject that enrolled in the study obtained pre- and post-procedure complete blood count (CBC), platelets, and chemistries (Panel-7), including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), glucose (Glu), and liver function tests (LFTs), prior to and ~24 h after the procedure to monitor for potential peptide toxicity. After esophageal intubation, a 10 second video was collected in the white light mode. Then, ~3 ml of peptide with sequence “ASYNYDA” at a concentration of 10 μM was administered topically to the distal esophagus using a mist spray catheter. After 10 minutes for incubation, the unbound peptide was gently rinsed off with water, and another 10 second video was collected of the fluorescence image that localized peptide binding. Fig. 4A shows a conventional white light image of Barrett’s in the distal esophagus in vivo, where no distinct architectural lesions can be appreciated. Fig. 4B shows the corresponding NBI image of the same region of the esophagus, and highlights the presence of intestinal metaplasia, as distinguished by the brown color, but this image is not sensitive to the presence of dysplasia. In Fig. 4C, the fluorescence image collected following topical administration and incubation of the peptide reveals a region of high grade dysplasia. Targeted biopsies were then collected, and dysplasia was confirmed by two gastrointestinal pathologists.

Fig 4. In vivo localization of peptide binding to high grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus on wide area endoscopy.

(A) A conventional white light endoscopic image of Barrett’s esophagus shows no evidence of pre-malignant lesions. (B) Narrow band image (NBI) of same region shows improved contrast highlighting intestinal metaplasia but not dysplasia. (C) In vivo fluorescence image following topical administration and incubation with affinity peptide having sequence “ASYNYDA” reveals foci of high grade dysplasia.

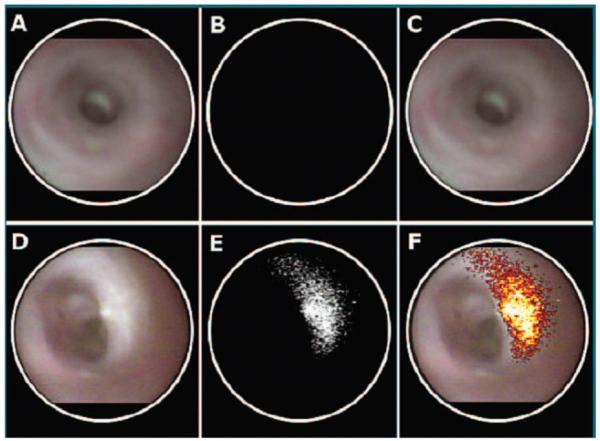

In addition, the use of confocal microscopy to validate binding of topically applied fluorescence-labeled peptides to dysplastic crypts has been demonstrated in vivo with sporadic colonic adenomas [44]. After IRB approval and informed consent, adult patients already scheduled for screening colonoscopy were recruited into the study. The same blood tests described above were performed to monitor for peptide toxicity. When an adenoma was seen on white light colonoscopy, ~3 ml of the fluorescence-labeled peptide with sequence “VRPMPLQ” at a concentration of 100 μM was administered topically to the adenoma and surrounding normal mucosa. After 10 minutes for incubation, the unbound peptide was gently rinsed off with water, and the fibered confocal miniprobe was passed through the instrument channel, and placed into contact with the mucosa for collection of fluorescence images. Fig. 5A shows a white light endoscopic image of a colonic adenoma, used as a model for dysplasia. Fig. 5B shows an in vivo confocal image following staining with the fluorescence-labeled peptide that demonstrates binding to dysplastic (left half) and no binding to normal (right half) crypts, scale bar 20 μm. Fig. 5C shows a confocal image with control peptide (scrambled) with sequence “QLMRPPV” shows no binding.

Fig 5. In vivo validation of peptide binding to colonic adenoma on confocal microscopy.

(A) Conventional white light endoscopic image of colonic adenoma. (B) In vivo confocal image following topical application and incubation of fluorescence-labeled affinity peptide with sequence “VRPMPLQ” shows binding to dysplastic (left half) and no binding to normal (right half) crypts. (C) Confocal image with control peptide (scrambled) with sequence “QLMRPPV” shows no binding to adenoma, scale bar 20 μm. Used with permission [44].

Regulatory Oversight

The potential knowledge to be gained by imaging the pattern of expression of molecular targets in the digestive tract is tremendous. However, caution must be exercised when pursuing investigation in human subjects to validate in vivo probe activity. The use of exogenous probes, such as protease-activated, antibodies, and peptides, as targeting agents require additional regulatory oversight beyond that provided by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB). While topical application of the molecular probes in the digestive tract is much safer than intravenous, there remains some risk for a local reaction. Furthermore, the possibility of systemic toxicity will depend on the absorption and internalization properties of the specific probe. An investigational new drug (IND) application should be submitted to the FDA prior to the beginning of the study [51]. The contents of this application include an introductory statement, general investigational plan, study protocol, chemistry manufacturing and control (CMC) data, pharmacology and toxicology information, and any previous human experience. The introductory statement and general investigational plan provides a brief discussion of the study aims with sufficient background so that the FDA can understand the scope of the developmental plan and to anticipate the future needs of the sponsor. The study protocol provides details about how clinical validation is to be performed, and includes the number of subjects, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing, monitoring (blood tests and survey), and stopping rules. The protocol for a Phase 1 study, whose goal is primarily to demonstrate safety, has flexibility to allow the sponsor to learn about probe function in vivo so that refinements can be made. The CMC provides details about the proper identification, quality, purity, stability, and concentration of the investigational probe, and the pharmacology section describes the probe’s mechanism of action and provides information about its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. In addition, an animal toxicology study, typically performed in rats, is needed to support the safety of the molecular probe prior to introduction in human subjects. Finally, data from previous human experience can be provided if it exists.

Summary and Future Directions

In summary, a number of promising intracellular and cell surface targets expressed by the mucosa of the digestive tract have been identified that can reveal evidence of neoplastic transformation on endoscopic imaging. Exogenous probes are needed to interact with these targets, and novel fluorescence instruments, including wide area endoscopy and confocal micrsocopy, are required for detection. Several classes of probes discussed in this text include protease-activated, antibody, and peptides. In addition, probes based on nanoparticle, aptamer, and small molecule platforms are also under development for this purpose. This novel, integrated imaging strategy promises to play an increasingly more important role in the future management of patients who have an increased likelihood of developing cancer, including risk stratification, early detection, therapeutic monitoring, and evaluation of recurrence. The use of targeted imaging reveals functional information about the mucosa based on patterns of molecular expression, and in combination with the architectural features provided by conventional reflected white light images, physicians will soon have a powerful new tool for diagnosing and treating patients with diseases of the digestive tract, including Barrett’s esophagus, atrophic gastritis, and ulcerative colitis, in manner that has up until now been inadequate. In order to achieve these aims, more progress is needed in the development of molecular probes with high specificity, including improvement in target-to-background ratio, enhancement in delivery efficiency, and characterization of toxicity profiles. Also, a greater understanding is needed of the significance and timing of the over expressed targets. In addition, improved endoscopic instruments that have multi-spectral detection capabilities and deeper tissue penetration imaging will be required. Finally, issues of inter-observer variability, clinical efficacy, and cost effectiveness should be addressed with randomized, multi-center, controlled trials to validate and standardize the imaging methods. These promising techniques have great potential to improve the detection sensitivity, increase surveillance efficiency, and ultimately achieve better patient outcomes for management of cancer in the digestive tract.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. K08 DK067618 and R03 CA096752 from the National Institutes of Health and the Clinical Scientist Translational Research Award from Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

References

- 1.Sivak MV. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Past and Future. Gut. 2006;55(8):1061–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed W. B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine DS, Haggitt RC, Blount PL, et al. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jess T, Loftus EV, Jr, Velayos FS, et al. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from olmsted county, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4):1039–46. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):789–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serafini AN, Klein JL, Wolff, et al. Radioimmunoscintigraphy of recurrent, metastatic, or occult colorectal cancer with technetium 99m-labeled totally human monoclonal antibody 88BV59: results of pivotal, phase III multicenter studies. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1777–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willkomm P, Bender H, Bangard M, et al. FDG PET and immunoscintigraphy with 99mTc-labeled antibody fragments for detection of the recurrence of colorectal carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(10):1657–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A. In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(4):375–8. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bredow S, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of proteolytic enzyme activity using a novel molecular reporter. Cancer Res. 2000;60(17):4953–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bremer C, Bredow S, Mahmood U, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Optical imaging of matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity in tumors: feasibility study in a mouse model. Radiology. 2001;221(2):523–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2212010368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang HW, Torres D, Wald L, Weissleder R, Bogdanov AA. Targeted imaging of human endothelial-specific marker in a model of adoptive cell transfer. Lab Invest. 2006;86(6):599–609. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laxman B, Hall DE, Bhojani MS, Hamstra DA, Chenevert TL, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. Noninvasive real-time imaging of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16551–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messerli SM, Prabhakar S, Tang Y, Shah K, Cortes ML, Murthy V, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Tung CH. A novel method for imaging apoptosis using a caspase-1 near-infrared fluorescent probe. Neoplasia. 2004;6(2):95–105. doi: 10.1593/neo.03214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maley CC, Galipeau PC, Finley JC, et al. Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2006;38(4):468–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacomini CP, Leung SY, Chen X, et al. A gene expression signature of genetic instability in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9200–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald RC. Molecular basis of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2006;55(12):1810–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syngal S, Clarke G, Bandipalliam P. Potential roles of genetic biomarkers in colorectal cancer chemoprevention. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2000;34:28–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(2000)77:34+<28::aid-jcb7>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruszewski WJ, Rzepko R, Wojtacki J, Skokowski J, Kopacz A, Jaśkiewicz K, Drucis K. Overexpression of cathepsin B correlates with angiogenesis in colon adenocarcinoma. Neoplasma. 2004;51(1):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKerrow JH, Bhargava V, Hansell E, Huling S, Kuwahara T, Matley M, Coussens L, Warren R. A functional proteomics screen of proteases in colorectal carcinoma. Mol Med. 2000;6(5):450–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kioi M, Yamamoto K, Higashi S, Koshikawa N, Fujita K, Miyazaki K. Matrilysin (MMP-7) induces homotypic adhesion of human colon cancer cells and enhances their metastatic potential in nude mouse model. Oncogene. 2003;22(54):8662–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanioka Y, Yoshida T, Yagawa T, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 are associated with unfavourable prognosis in superficial oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(11):2116–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folli S, Wagnières G, Pèlegrin A, et al. Immunophotodiagnosis of colon carcinomas in patients injected with fluoresceinated chimeric antibodies against carcinoembryonic antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(17):7973–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito S, Muguruma N, Kusaka Y, et al. Detection of human gastric cancer in resected specimens using a novel infrared fluorescent anti-human carcinoembryonic antigen antibody with an infrared fluorescence endoscope in vitro. Endoscopy. 2001;33(10):849–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sagara M, Yonezawa S, Nagata K, et al. Expression of mucin 1 (MUC1) in esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma: its relationship with prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1999;84(3):251–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990621)84:3<251::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utsunomiya T, Yonezawa S, Sakamoto H, et al. Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 mucins in gastric carcinomas: its relationship with the prognosis of the patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(11):2605–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schechter AL, Hung MC, Vaidyanathan L, Weinberg RA, Yang-Feng TL, Francke U, Ullrich A, Coussens L. The neu gene: an erbB-homologous gene distinct from and unlinked to the gene encoding the EGF receptor. Science. 1985;229(4717):976–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2992090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu D, Hung MC. Overexpression of ErbB2 in cancer and ErbB2-targeting strategies. Oncogene. 2000;19(53):6115–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortega P, Morán A, de Juan C, et al. Differential Wnt pathway gene expression and E-cadherin truncation in sporadic colorectal cancers with and without microsatellite instability. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):995–1001. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marten K, Bremer C, Khazaie K, Sameni M, Sloane B, Tung CH, Weissleder R. Detection of dysplastic intestinal adenomas using enzyme-sensing molecular beacons in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(2):406–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alencar H, Funovics MA, Figueiredo J, et al. Colonic adenocarcinomas: near-infrared microcatheter imaging of smart probes for early detection--study in mice. Radiology. 2007;244(1):232–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441052114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuusela P, Jalanko H, Roberts P, et al. Comparison of CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in the serum of patients with colorectal diseases. Br J Cancer. 1984;49(2):135–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichelt U, Duesedau P, Tsourlakis MCh, et al. Frequent homogeneous HER-2 amplification in primary and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(1):120–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pegram MD, Reese DM. Combined biological therapy of breast cancer using monoclonal antibodies directed against HER2/neu protein and vascular endothelial growth factor. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(3 Suppl 11):29–37. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.34053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emlet DR, Brown KA, Kociban DL, et al. Response to trastuzumab, erlotinib, and bevacizumab, alone and in combination, is correlated with the level of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(10):2664–74. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0079. 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauser S, Weis R, Braselmann H, et al. Significance of HER2 low-level copy gain in Barrett’s cancer: implications for fluorescence in situ hybridization testing in tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5115–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arteaga CL, O’Neill A, Moulder SL, et al. A Phase I-II Study of Combined Blockade of the ErbB Receptor Network with Trastuzumab and Gefitinib in Patients with HER2 (ErbB2)-Overexpressing Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(19):6277–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medina PJ, Goodin S. Lapatinib: a dual inhibitor of human epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. Clin Ther. 2008;30(8):1426–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funovics M, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Protease sensors for bioimaging. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377(6):956–63. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. http://www.visenmedical.com.

- 40.Keller R, Winde G, Terpe HJ, Foerster EC, Domschke W. Fluorescence endoscopy using a fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibody against carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with colorectal carcinoma and adenoma. Endoscopy. 2002;34(10):801–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bando T, Muguruma N, Ito S, et al. Basic studies on a labeled anti-mucin antibody detectable by infrared-fluorescence endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(4):260–9. doi: 10.1007/s005350200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly K, Alencar H, Funovics M, Mahmood U, et al. Detection of invasive colon cancer using a novel, targeted, library-derived fluorescent peptide. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6247–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu S, Wang TD. In Vivo Cancer Biomarkers of Esophageal Neoplasia. Cancer Biomarkers. 2008 doi: 10.3233/cbm-2008-4606. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsiung PL, Hardy J, Friedland S, Soetikno R, Du CB, Wu AP, Sahbaie P, Crawford JM, Lowe AW, Contag CH, Wang TD. Detection of colonic dysplasia in vivo using a targeted heptapeptide and confocal microendoscopy. Nat Med. 2008;14(4):454–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller R, Winde G, Terpe HJ, Foerster EC, Domschke W. Fluorescence endoscopy using a fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibody against carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with colorectal carcinoma and adenoma. Endoscopy. 2002;34(10):801–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito S, Muguruma N, Kimura T, et al. Principle and clinical usefulness of the infrared fluorescence endoscopy. J Med Invest. 2006;53(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.2152/jmi.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uedo N, Higashino K, Ishihara R, et al. Diagnosis of Colonic Adenomas by New Autofluorescence Imaging System: a Pilot Study. Digestive Endoscopy. 07;19(S1):S134–8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pawley J, editor. Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy. 3rd ed Plenum; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiesslich R, Burg J, Vieth M, et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(3):706–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang TD, Friedland S, Sahbaie P, Soetikno R, Hsiung PL, Liu JT, Crawford JM, Contag CH. Functional imaging of colonic mucosa with a fibered confocal microscope for real-time in vivo pathology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1300–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. http://www.fda.gov/CDER.