Abstract

Collaborating with community stakeholders is an often suggested step when integrating cultural variables into psychological treatments for members of ethnic minority groups. However, there is a dearth of literature describing how to accomplish this process within the context of substance abuse treatment studies. This paper describes a qualitative study conducted through a series of focus groups with stakeholders in the Latino community. Data from focus groups were used by researchers to guide the integration of cultural variables into an empirically-supported substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents currently being evaluated for efficacy. A model for culturally accommodating empirically-supported treatments for ethnic minority participants is also described.

In the psychological treatment literature in general (G. Bernal, Jimenez-Chafey, & Rodriguez, 2009; G. Bernal & Saez-Santiago, 2006; Hall, 2001; Lau, 2006) and the substance abuse treatment literature in particular, many advocate the need to modify existing treatments for individuals from ethnic minority groups (Castro & Garfinkle, 2003; Freeman, Lewis, & Colon, 2002). Most empirically-supported treatments1 for substance abuse were developed and tested within in the context of the European American perspective. The current literature does not provide clear of evidence that empirically-supported treatments are also efficacious with ethnic minority groups. Further, there is relatively little empirical evidence for the support or lack thereof for the cultural modification of substance abuse treatment for ethnic minority individuals. Therefore, we are left with mostly theoretical conjecture regarding the empirical effectiveness of integrating cultural variables into psychological treatments.

The lack of clear guidelines to culturally modify existing treatments presents an additional problem for substance abuse treatment researchers. Despite theoretically-based suggestions for adjustment or modification (G. Bernal et al., 2009), there is a dearth in the substance abuse treatment literature of examples of how to accomplish this. For example, one frequently stated argument is to collaborate with the “community” to understand the needs of ethnic minority clients prior to treatment implementation (see Freeman et al., 2002). Unfortunately, this suggestion is infrequently carried out in substance abuse treatment studies.

To address some of the limitations identified above this paper describes the first of a set of three studies on the cultural accommodation of an empirically-supported cognitive-behavioral substance abuse treatment being tested for efficacy with Latino adolescents2. First, this paper will describe a conceptual model for integrating cultural variables into treatment. Next, we describe how collaborating with community stakeholders, a necessary component of the model, was accomplished via a qualitative study. Finally, we will outline the identified cultural variables and how these cultural variables were implemented through accommodation practices, specifically in terms of treatment delivery and content. It is our hope that sharing the information in this paper will encourage more professional dialogue and action among researchers grappling with the issues of cultural accommodation or modification of empirically-supported substance abuse treatments.

Culturally Appropriate Terms

There are many terms used to refer to the process of culturally modifying a psychological treatment. For example, cultural adaptation, accommodation or translation as well as culturally sensitive, congruent, competent, specific or appropriate are all terms that have been used to describe this process. This list is not exhaustive but illustrates that a common term does not currently exist in the treatment literature. For this paper, the term cultural accommodation is utilized and defined as: “the process of adjusting components of an intervention to increase congruency with the cultural norms of a particular group.” Cultural accommodation aims to enhance the cultural congruency between a treatment and a specific ethnic group through the process of identifying and integrating culturally relevant variables into an empirically-supported treatment with the intent of increasing the efficacy of the treatment for that population.

In contrast, the term cultural adaptation is more commonly used to describe the process of modifying empirically-supported treatments to increase relevancy for individuals from ethnic minority groups with whom they were not developed or tested. For the purposes of this paper, cultural adaptation is defined as: “modifying the underlying structure of an intervention to increase correspondence with the cultural norms of a particular group” and a conscious decision was made not to adopt this term for many reasons. First, there is a need to test empirically-supported treatments with individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds with whom they were not originally developed in order to further the limited knowledge base in this area (Hall, 2001; Miranda et al., 2005; Whaley & Davis, 2007). Ignoring well-established treatment approaches because they were not originally developed or tested with an ethnic minority population may unnecessarily cause researchers to duplicate previous work as interventions often consist of some universal elements (Dumas, Rollock, Prinz, Hops, & Blechman, 1999; Leong, 2007). Further, some studies demonstrate that individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds experience positive outcomes without the integration of cultural variables into treatment (Whaley & Davis, 2007). Second, cultural adaptation is more analogous to developing a new treatment rather than making an established treatment more culturally congruent. Based on the limited empirical data that exist regarding outcomes for ethnic minorities with established treatments, developing new treatments is too large of a leap to make at this time (Miranda et al., 2005; Whaley & Davis, 2007). Finally, there is a need to identify which culturally-specific variables are most relevant for ethnic minority clients in improving the efficacy of empirically-supported substance abuse treatments (Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Freeman et al., 2002).

Conceptual Framework

The current study is based on the stage model approach for the development of behavioral treatments that includes the following steps: manual development/refinement, completion of a pilot study, and efficacy testing with a randomized clinical trial (RCT; Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001). This approach provides a systematic method for developing and testing behavioral treatments in general; however, suggestions are lacking for the cultural accommodation of substance abuse treatments. Some scholars argue that consultation with the local ethnic minority stakeholders in the community, who understand the most pressing community needs, is a necessary but often neglected step in the cultural accommodation of substance abuse treatment programs (Castro & Garfinkle, 2003; Freeman et al., 2002). Unfortunately, many of the studies on cultural adaptation of treatment utilize the more traditional approach of using researchers’ knowledge and the literature to develop and implement psychological treatments with ethnic minorities (see Cardemil, Kim, Pinedo, & Miller, 2005; Gil, Wagner, & Tubman, 2004; Santisteban, Mena, & Suarez-Morales, 2006) and provide limited or vague descriptions of the actual adaptations made to the interventions (Huey & Polo, 2008). In this paper, it is suggested that one of the reasons pre-treatment collaboration with ethnic minority stakeholders in the community occurs infrequently is because of the time and effort this process takes.

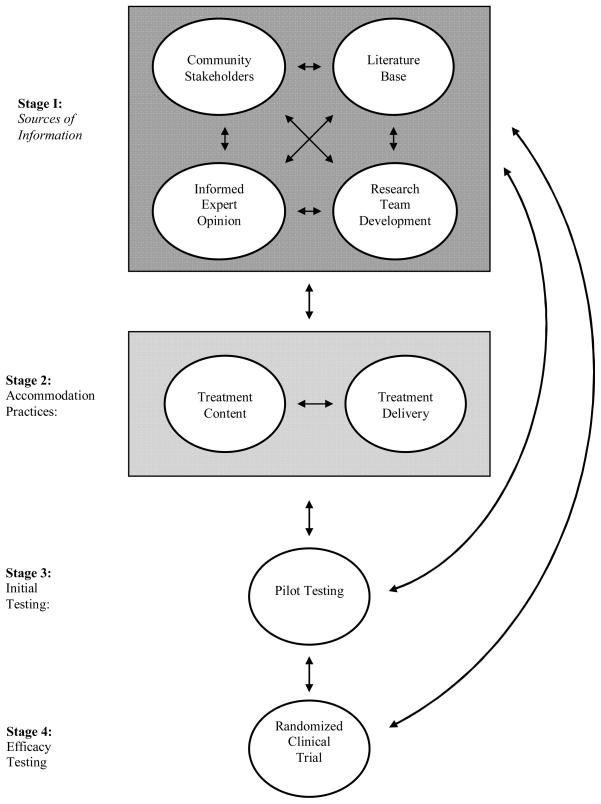

In the psychological treatment literature many have suggested general guidelines (G. Bernal & Saez-Santiago, 2006; Hall, 2001; Lau, 2006) rather than specific methodology to guide the development and testing of culturally accommodated interventions. Using some of these general guidelines found in the literature the following cultural accommodation model was developed to inform and guide the current study (see Figure 1). As can be seen from Figure 1, the cultural accommodation model consists of four interrelated stages: sources of information, accommodation practices and empirical testing (2 stages).

Figure 1.

Cultural Accommodation Model for Substance Abuse Treatment

The first stage of the model, sources of information, consists of four components: community stakeholders, literature base, informed expert opinion and research team development. The goal of this stage is to identify the most relevant cultural variables from multiple sources that will be integrated into an empirically-supported treatment. The first component, community stakeholders, involves collecting data from individuals in the community who can inform the cultural accommodation of the treatment prior to a RCT being conducted. Qualitative methods are frequently suggested as a means for collecting data from community stakeholders (Freeman et al., 2002; Lau, 2006; Wagner et al., 2008) and are the primary focus of this paper. Qualitative methods allow the stakeholders to express their concerns and suggestions directly to the researcher. The second component, literature base, consists of review of the current theoretical and empirical literature that is already common to researchers. The third component, informed expert opinion, provides opportunity for the researcher to consult with his/her colleagues outside of the research team (e.g., senior researchers in the addictions field) regarding the cultural accommodation of the intervention Finally, research team development, encourages the researcher to have on-going discussions with research team members at all levels (e.g., Co-PI’s, therapists, assessors, research assistants) to identify ways the cultural variables of interest will be integrated into the treatment. It is important that researchers talk with as many team members as possible, while maintaining appropriate methodological rigor, because in many treatment studies the “front-line” staff (e.g., assessors, research assistants) have more direct contact with participants than PI’s and can provide valuable cultural insights. The next stage of the model, accommodation practices, begins when the relevant cultural variables have been identified for investigation by completing the sources of information stage.

The primary goal of the accommodation practices stage of the model is to integrate the cultural variables indentified in the prior stage into the empirically-supported treatment. This can also be conceptualized as increasing the social validity of an intervention thru integration of cultural variables based on the assumption that ethnic minority participants are more likely to engage with treatments they find culturally relevant (Lau, 2006). The integration of cultural variables occurs via the two components of this stage, that is, treatment delivery and treatment content. Treatment delivery consists of implementing methods to successfully engage ethnic minority participants into the intervention. For example, an intervention may take place in a local community center or school rather than in a therapist’s office to increase the ease of access for participants. Modifying the treatment delivery is an important component given the difficulties associated with recruitment and retention of ethnic minorities documented in the treatment literature (Hall, 2001; Miranda, Azocar, Organista, Munoz, & Lieberman, 1996). In fact, Hall (2001) argues that low participation rates give the impression that there is something wrong with ethnic minorities compared to whites when they do not want to enroll in treatment programs. Thus, there is a need for researchers to design treatment studies that are culturally attractive and relevant to ethnic minority participants (Lau, 2006).

The treatment content component refers to the ways in which the identified cultural variables are integrated into an already existing empirically-supported treatment protocol or manual. This component is based on the suggestion that treatment content should culturally reflect the experiences, values and beliefs of the targeted ethnic minority group (G. Bernal & Saez-Santiago, 2006; Hall, 2001; Lau, 2006) while not modifying the underlying theoretical or skill-based components of the intervention. For example, the identified cultural variables in the current study were integrated into an empirically-supported cognitive-behavioral substance abuse treatment that has primarily been tested with Anglo adolescents (Dennis et al., 2004; Kaminer, Burleson, Caryn, Sussman, & Rounsaville, 1998). The intervention that incorporates the cultural variables (i.e., the accommodated treatment) is currently being compared to a standard version of the CBT treatment without cultural accommodations for Latino adolescents. The specific ways in which the cultural variables are integrated into treatment content is described below.

The last two stages of the model, initial testing and efficacy testing, are concerned with conducting social and efficacy testing of the accommodated treatment versus the standard treatment. The goal of the initial or pilot testing stage is to evaluate things such as recruitment, retention/engagement, participant satisfaction and initial efficacy of the intervention (Rounsaville et al., 2001). This has also been referred to as testing the social validity of the intervention (Lau, 2006). Results from a pilot study can then be used to inform the researcher when conducting a subsequent randomized clinical trial to establish treatment efficacy (Rounsaville et al., 2001). Details regarding the on-going pilot and efficacy studies, based on the culturally accommodated treatment described here, will be the focus of future papers.

The cultural accommodation model presented above provides a context for the present study. More specifically, a qualitative study was conducted to obtain information from community stakeholders on relevant cultural variables that were subsequently integrated into an empirically-supported substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents. As mentioned above, obtaining information from the local community is often suggested but rarely practiced in substance abuse treatment research. This study sought to fill this gap in the literature by collaborating with Latino community stakeholders prior to the initiation of the intervention phase of the treatment study.

Method

Collaborating with Community Stakeholders

The present study was designed to engage community stakeholders in order to gain information necessary for the integration of cultural variables into an empirically-supported substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents. A qualitative method was employed to accomplish this goal and focus groups were chosen as the format for eliciting this information. Three major community groups were identified as partners with unique cultural knowledge to contribute. These were (a), the local Latino community itself consisting of community leaders, parents and adolescents, (b) the juvenile justice system, consisting of administrators, judges and probation officers, and (c) local substance abuse treatment providers who offer services to Latino adolescents and their families.

Developing relationships

It took approximately five months to initiate and foster relationships with community stakeholders prior to the first focus group being conducted. The initial recruitment process included the researchers utilizing personal connections in the community, making phone calls, e-mailing, mailing study information and attending community meetings to provide information about the project. During each interaction with community stakeholders, researchers shared the purpose of the study, brainstormed ways that the study could benefit Latino adolescents and how the study personnel and community stakeholders could work together in a mutually beneficial relationship. Very little “selling” of the project was needed because most stakeholders voiced a need to address the issue of substance abuse treatment services for Latino adolescents and expressed appreciation of the efforts made by the researchers to listen and learn from them.

Recruiting

To assist with the recruitment process, each participant was offered $30 for participation in the focus groups. The adolescent and parent participants were recruited from a juvenile justice early intervention program for Latino families parenting adolescents at-risk for problem behavior, including substance abuse. The adolescent (N = 13) and parent (N = 18) focus groups were conducted concurrently but separately during one of the early intervention program’s weekly meetings. In the parent focus group, 75% reported that their adolescent was involved in the juvenile court system. Only one adolescent indicated prior experience with substance abuse treatment on the self-report demographic forms that were administered immediately prior to the focus group. However, based on the qualitative responses given during the focus group, this number was likely much higher. This type of inconsistency is not unsurprising given the research that suggests adolescents initially underreport substance use (Stinchfield, 1997; Winters, 2001).

To recruit Latino community leaders, researchers compiled a list of potential participants based on their knowledge of the community and from searching community web pages. The initial list was pared down to generate a more refined list of leaders with specific knowledge of the issues that Latino adolescents face related to drug use. Community leaders were then contacted with an introductory letter followed by a phone call. This process generated a total of eight participants; the final focus group consisted of seven participants and one participant was interviewed individually due to scheduling conflicts. The community leaders represented a variety of professional backgrounds including business, government, community activism, social services, education and the arts.

Probation officers and court administrators were recruited through researchers’ networking and outreach. First, researchers worked with upper level administrators to gain support for the study. Next, researchers developed relationships with frontline probation officers, specifically targeting officers who worked regularly with Latino adolescents. From this pool, two focus groups were conducted (N=5 and N=3) with probation officers due to participant scheduling conflicts. Each session was held at a juvenile court building, easily accessible to probation officers.

Substance abuse treatment providers were recruited through researchers’ networking during a monthly meeting providers regularly attended at the county division of substance abuse. This monthly meeting provided an opportunity for providers to collaborate, share resources and problem-solve about needs in the community. Researchers were invited to attend this meeting, by upper administration, in order to describe the study and recruit participants. Contact information from potential participants was obtained at this meeting and a focus group was scheduled for the following month immediately following the treatment provider meeting. In the interim, potential participants were contacted by researchers and provided more information about the study. From this pool, a focus group was conducted (N = 8) in the county government building immediately after the next monthly treatment provider meeting.

Conducting the Focus Groups

The objective of conducting the focus groups was to obtain data to assist the researchers in culturally accommodating an empirically-supported substance abuse treatment prior to testing it with Latino adolescents. In each 1 ½ hour session, it was quickly observed that the focus groups served a more immediate function of relationship building and establishing collaboration with community partners. Demographic information for focus group participants is presented in Table 1. The first author or another trained researcher facilitated the groups while a second researcher took written notes and audio-taped the discussion. All the focus groups except one were conducted at sites in the community in order to make participation convenient for community stakeholders and maximize attendance. Consent and assent were obtained from participants prior to the start of the sessions and the study was conducted in compliance with the first author’s university Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in Focus Groups

| Adolescents | Parents | Community Leaders | Probation Officers | Treatment Providers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Male | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Female | 5 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| Mean Age | 14.2 | 41.0 | 47.1 | 34.5 | 40.9 |

| Latino | 11 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Multi-Racial | 2 | -- | 1 | -- | -- |

| White | -- | -- | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Language used in focus group | Primarily English; some Spanish | Spanish | Primarily English; some Spanish | English | English |

Focus Group Scripts

Focus group scripts were developed through a combination of a literature review, brainstorming sessions with research team members and obtaining feedback from experts (Krueger & Casey, 2009; Morgan, 1997). Family, acculturation and ethnic identity have been identified as three of the more salient cultural variables with respect to substance treatment for Latinos (Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Gil, Tubman, & Wagner, 2001; Wagner et al., 2008) and questions about these variables were built into the scripts. The structure and questions of scripts across focus groups were similar except for minor wording changes to make them relevant for specific participant groups (e.g., adolescents, parents). Each script began with a brief introductory question tailored to the particular group, followed by two questions that guided participants toward the topic of interest. These questions were designed to gather general perceptions of the current generation of Latino adolescents and substance abuse treatment services available in the community. The next three questions addressed family, acculturation and ethnic identity as they related to substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents. A final question provided participants the opportunity to add any information not previously discussed.

Analytical Strategy

Morgan (1997) suggests that qualitative data analysis should be linked to the purpose of collecting the data and how it will be used. Therefore, a theme-based approach and related level of analysis was deemed appropriate as the data was used to guide the cultural accommodation of a treatment manual. Analyst triangulation was used so that the data was examined by three people in order to decrease the potential for bias from any one person (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Audio recordings were transcribed and compared to the written notes to produce an abridged transcript for each focus group. The principal investigator, project coordinator and a research assistant independently reviewed the transcripts for the purposes of familiarizing themselves with how they would combine the content into themes. Next, these reviewers collectively coded the transcripts into themes using a consensus approach. If the placement of content into a particular theme did not achieve consensus agreement then a majority vote decided. The theme-based results of this analysis were independently examined by the principal investigator and program coordinator who refined the general themes into sub-themes. These two people discussed the resulting themes and sub-themes to resolve any disagreements prior to the final results.

Results

Data analysis revealed five major themes, the three anticipated themes of family, acculturation and ethnic identity and two additional themes of perceptions of substance abuse treatment and barriers to treatment. Data from the focus groups were used to complete the sources of information stage of the cultural accommodation model which subsequently led to completion of the accommodation practices stage. The focus group themes and corresponding accommodation practices are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Focus Group Themes and Corresponding Accommodation Practices

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Accommodation Practice | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family |

|

Treatment Content and Delivery | C*: Infused role-plays that included relevant family situations D: Increased contact with parents/adolescents via phone calls, mailings and an initial parent meeting. |

| Acculturation |

|

Treatment Content | Infused role-plays more relevant to Latino adolescents (e.g., hearing racist comments) and discussion of stressors related to issues of acculturation (e.g., language bartering) |

| Ethnic Identity |

|

Treatment Content | Development of new module addressing issues of ethnic identity and ways to develop strengths and be aware of perceived negativities (e.g., racism, discrimination); therapist weaves issues of racism and discrimination throughout treatment |

| Substance Abuse Treatment |

|

Treatment Content and Delivery | C: Drug refusal skills module was revised to include drug education information; development of ethnic identity module D: Language preference asked at time of referral; all materials in English/Spanish |

| Barriers to Services |

|

Treatment Delivery | D: Bilingual staff interacting with parents/adolescents, scheduling based on needs of family (e.g., night, weekends); bus tokens provided for transportation; treatment conducted at community center |

Note. C = Treatment Content and D = Treatment Delivery

Family Theme

Participants described ways the family influences the experiences of Latino adolescents in substance abuse treatment and the following sub-themes emerged: parental involvement and support, family dynamics and values and family risk factors. Participants across groups commented about the importance of parental involvement and parental support in treatment. Parents commented on the high value they place on their children and how much they care for them and want them to make good choices.

The probation officers, and some participants from the other adult focus groups, commented that they perceived Latino families as collectivistic in nature and that parenting roles are flexible within extended Latino families. For example, one probation officer said:

“The American society is very mom, dad, kids and I think from what I have seen from the Hispanic families here is that they very much rely on other family members or close family friends who they grew up with and are taken in as family.”

In addition to the comments above, a few treatment providers and community leaders indicated that some Latino families may deny the existence of problems or may provide negative role-models such as a parent who also uses drugs; however, they agreed that this issue was not limited to Latino families. Data from the family theme was used to enhance treatment content and delivery by increasing the emphasis placed on family-related content in the treatment manual and building in more frequent contact (including phone calls, mailings and a parent meeting prior to treatment) between treatment staff and parents to bolster engagement, communication and support.

Acculturation Theme

Participants noted how acculturation or amount of time in the U.S. influences the experiences of Latino adolescents in substance abuse treatment and the following sub-themes emerged: differences in laws and social rules, clash between family and children and generational language differences. Many probation officers, some parents and some treatment providers noted the differences in laws and social norms in the U.S. compared to countries of origin. For example, participants explained that in Mexico it was okay for adolescents to drink alcohol or buy tobacco whereas adolescents could not do so in the U.S. Parents also spoke about being unfamiliar with the laws and social norms regarding children in the U.S. such as disciplinary practices. For example, one probation officer said

“It’s not like there aren’t any laws [outside of the U.S.] but a lot of the kids do a lot of different things. Like, I went down [to Mexico] to visit when I was 18, my grandpa sent my cousin, who was seven, down [to the store] to buy cigars for him and that’s okay. They [youth] can go down and do that and then they get here and they feel like they are being held back because they are not being treated as adults.”

Probation officers, treatment providers, and community leaders also highlighted the problems that Latino families experience due to differential rates of language acquisition. In particular, probation officers observed that parents often speak only Spanish whereas the adolescents speak English and Spanish which creates language and cultural divisions between the parent and adolescent. This often results in the adolescent being responsible for navigating English speaking environments with limited support from parents due to the language barrier. One community leader described it this way:

“By that I mean, you find, when a 4th grader has to interpret for his dad and the dad has always been the patriarch and always made the decisions or even the mother, that throws a different color on it and it causes some problems within which I am not totally sure what they are.”

Interestingly, when asked about acculturation both parents and adolescents commented that they did not perceive this issue to impact how adolescents experienced treatment because drug problems are the same for everyone. Data from the acculturation theme was used to enhance treatment content. Specifically, material and skill-based role-plays that have cultural relevance for Latino adolescents and address issues of acculturative stress were infused in the treatment content (e.g., norms in other countries vs. U.S., hearing racist comments; translating for a parent).

Ethnic Identity Theme

Participants described ways that identification with an ethnic group influences the experiences of Latino adolescents in treatment and the following sub-themes emerged: identification of self, a lack or loss or identity and values and the importance of ethnic identity. Some disagreement arose across groups regarding the ways in which Latino adolescents identified themselves although many descriptions shared recognition of the country of origin as important for identification. Treatment providers and probation officers indicated that they perceived many Latino adolescents to have a lack or a loss of identity which they believed to be related to being part of two different cultures. They further commented that this bi-cultural experience creates problems for Latino adolescents in developing an identity because they receive messages, sometimes contradictory, from each culture. There was also recognition that some youth find an identity in gang membership that can serve as a surrogate family. One probation officer described the identity struggles Latino adolescents experienced this way:

“They are trying to find themselves as adolescents and then you throw in the cultural aspects as well. Am I Mexican or Dominican or am I American? Which culture am I?”

A community leader commented on the negative messages Latino adolescents receive about themselves:

“[They] are being told they are not good enough…either they are not smart enough at school, they’re not good enough because they don’t wear particular clothes, either they are not good enough because they may or may not have an accent, or don’t read well.”

Some parents indicated that it is important for adolescents to be proud of their heritage and that parent’s fear that this part of their identity will be lost as they become more disconnected from their Latino background. One parent described the way she integrated cultural elements of Mexico with her family:

“…we play games from Mexico, la loteria, my kids love it. Things that you instill in your children [are important]. They are excited to learn about our culture. Besides spending time together as a family, we are teaching them about our country’s culture.”

About half of the adolescent participants stated that people from the same cultural background understand each other better and would benefit from treatment designed for Latino adolescents. In contrast, half of the adolescents indicated everyone should receive the same type of treatment regardless of cultural background. Data from the ethnic identity theme was used to enhance treatment content through increasing awareness of risk factors that Latino adolescents face (e.g., racism, discrimination) and development of a new module, Ethnic Identity and Adjustment. This module addresses issues of identity development from a Latino adolescent perspective and includes content and skills to bolster personal strengths and challenge negative stereotypic messages.

Substance Abuse Treatment Theme

Participants described their perceptions of substance abuse treatment services and two sub-themes emerged: content and delivery. Regarding content, adolescent participants and some parents indicated that programs should include information about the effects that drugs have on the brain and body. One adolescent commented that learning this type of information made him stop using drugs. Adolescents also suggested that treatment programs provide “real-life” examples of the negative consequences of drug use. One example included exposing youth in treatment to persons who suffered from the negative physical consequences of drug use (e.g., meth teeth). Most adolescents and some parents agreed that statements such as “just say no” are not effective. In particular, one adolescent described his frustration with the messages he has received about drugs:

“Everyone that’s involved says drugs are bad. Well, you already know drugs are bad they don’t have to tell you again and again…it just gets annoying. It’s like it goes in one ear and out the other. Like I heard it and I don’t care.”

Another adolescent said this:

“Show us the effects of it, don’t just sit there and say ‘Oh, it will mess up your brain and your lungs, but actually show it.”

A female adolescent stated that drug testing, such as urine analysis, was important for teens with drug problems to experience and was the only thing that made her stop using. Both adolescents and parents stated that treatment programs should provide information on the positive benefits of engaging in non-drug use activities rather than just providing messages that drugs are bad.

Regarding substance abuse treatment delivery, probation officers, community leaders and parents commented on the need for service providers to have high quality training to effectively work with adolescents. There was further agreement that therapists who provide services to Latino clients need to be culturally competent which includes being bilingual (English/Spanish) and incorporating culture in the treatment. However, many commented that therapist bilingualism was not indicative of cultural competency and there had been experiences of observing Anglo therapists who spoke “beautiful Spanish” but did not know many of the cultural nuances (e.g., importance of interpersonal connectedness) when working with Latino families. For example, one probation officer offered this comment regarding the level of cultural competence provided by some treatment agencies:

“It’s a little disappointing that we say that [cultural competency] is a need to [treatment] providers and then the best they can do is say, ‘Well, we’ll try to hire someone who speaks Spanish,’ as if that is cultural adaptation.”

Probation officers also commented on the overall lack of specialized substance abuse treatment services available to adolescents in their geographical region as compared to other specialized treatments (e.g., sex offender treatment).

The issue of language emerged again when discussing the delivery of substance abuse treatment services. For instance, probation officers, parents and some treatment providers commented on the need for treatment program staff and therapists to speak English and Spanish to ensure clear communication with parents, who often only speak Spanish. They explained that communication difficulties often resulted in a lack of understanding between families and providers which often made the development of trust difficult. Many participants described a general feeling of mistrust of systems and providers. One community leader described this lack of trust that can develop between the court, treatment providers and Latino adolescents:

“I think we [Latino’s] are criminalized at a very young age and so if you are in a situation where you are being told by a judge or the state that you need to do a treatment program and you are being put there by the system that you have already learned that you can’t trust these people, there is not a lot of reason for you to invest in that to start with whether or not it is a great [treatment] program.”

Many community leaders stressed that treatment programs should foster more positive interaction and communication with parents of the Latino adolescents in treatment. Some argued that this connection was needed because many treatment approaches are focused only on the adolescent while parents are essentially “kept in the dark”, especially for Latino families when language barriers are so often an issue. The need for a connection between treatment providers and Latino parents was based on the premise that parents want to know specific ways they can support their children during and after treatment completion. Data from the substance abuse treatment theme was used to enhance treatment content and delivery. For example, the drug refusal skills module was revised to include information on the effects drugs have on the brain and body and titled Drug Education and Refusal. In addition, frequent contact between parents and therapists were built into the treatment protocol and parent/adolescent language preference was determined at the point of referral and honored thereafter.

Barriers to Treatment Theme

Participants described the barriers that limit access to substance abuse treatment and the following sub-themes emerged: cost, work and family obligations, language issues and a general lack of services. Parents and probation officers indicated high cost as a major barrier in seeking treatment. Some parents and probation officers indicated that it was less expensive to seek treatment after becoming involved with the court system because the justice system covered much of the cost. One parent described her experience of obtaining treatment for her adolescent thru the courts:

“If you send them [to treatment], it cost[s] much more for you to send them than if the court sends them, a lot more.”

Another parent shared this example:

“I have asked her [my sister-in-law] why she doesn’t do anything for her children [send to substance abuse treatment], and she says, ‘It’s because I don’t have enough money, and that it is very expensive.”

In addition, some parents and probation officers indicated that working multiple jobs and lack of child-care were common barriers limiting parents’ participation in their adolescent’s treatment. One probation officer indicated that money and time were two common barriers that many Latino parents faced:

“They [Latino parents] don’t have a lot of money so a lot of them are caught where mom and dad are working multiple jobs just to make ends meet, so [treatment providers should] be considerate of their time.”

Another probation officer described barriers related to transportation:

“We have our cars, so simple things like transportation [are easier] where they [Latino parents] rely heavily on cars that aren’t registered, buses, everything that you can imagine to get places. So a meeting out here in [name of city] which for us might be [a] five minute drive, for them might be an hour, two hour bus ride depending on if they have to wait because a lot of them don’t have those means to get around.”

Probation officers reported that minimal Spanish language services were available at all levels of the court system; some indicated that even when court interpreters were available their skill and ability varied greatly. For example, one probation officer said that she observed a few court interpreters translating only the “bare minimum” and this only served to limit a parent’s understanding of the court’s sentencing guidelines or his/her role in the legal process. One broader repercussion of this communication barrier was that Latino parents’ were often perceived as “not caring” by court officials when, in fact, many parents simply did not understand what was expected of them. In particular, one probation officer explained that the term “temporary custody” is frequently used in juvenile court cases; however, the term can be mistakenly understood by Latino parents to mean that they have “lost custody” of their children and thus, their involvement should be limited in legal proceedings and treatment services. However, the intent of the court is exactly the opposite and there is an expectation that parents be involved in the legal proceedings of their children as well as treatment.

Bilingual probation officers said that they often translate for Spanish speaking families in court or at community appointments but, unfortunately, do not have the capacity to serve all the families with such translation needs. They further explained that when translation services are not available the adolescent (or another child) is often asked to translate for his/her parents. One probation officer stated that asking an adolescent to translate is particularly problematic when he/she has to convey information regarding his/her drug use or court imposed sanctions. In these instances, probation officers found that adolescents often did not accurately convey negative information to their parents.

Many probation officers, some community leaders and a few parents commented that the substance abuse treatment services available for adolescents were not especially accommodating of Latino families. Some of these examples included penalizing families for being late or bringing younger siblings to scheduled appointments with little recognition from the service providers that many Latino families may not have adequate transportation or child-care. Some participants noted that certain agencies did not make even minimal efforts to make Latino families feel more welcomed such as having a Spanish-speaking receptionist. Overall, there was consensus that treatment providers did not recognize the efforts made by many Latino parents to be involved in their youth’s treatment. One parent indicated a basic way that treatment providers could improve services:

“They [treatment providers] should speak Spanish with us, the parents. The children speak more English than Spanish.”

One of the community leaders took a broader view of treatment services for Latino adolescents:

“The system, programs for Latino youth, drug programs are very sparse, very poorly run and do not use the best methodology in existence.”

A probation officer observed:

“The services have not grown with the demographic either.”

Data from the barriers to services theme was used to enhance treatment delivery. For example, the research and treatment staff members interacting with Latino participants are bilingual and have prior experience working with Latino families. Scheduling for intakes, assessments and treatment group times are based on the needs of the families (e.g., evenings, weekends) in order to minimize disruption to work and other obligations. Transportation issues are addressed by providing bus tokens for adolescents attending group sessions and treatment is delivered in a community center in an area of the city where most of the participating families reside. Due to the central location of the treatment site adolescent participants have utilized the following modes of transportation to attend group sessions: transport by parent, riding the bus and riding a bike. Similar to other clinical research studies funded by a federal grant, there is no monetary cost to participants enrolled in the treatment program.

Discussion

The overall goal of the current study was to collect data from community stakeholders in order to inform the integration of cultural variables into an empirically-supported substance abuse treatment. The five themes that most clearly emerged from the focus groups were family, acculturation, ethnic identity as well as perceptions of substance abuse treatment and barriers to treatment. These themes were consistent with previous research or commentary from Latinos (Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Freeman et al., 2002; Wagner et al., 2008). This study was conducted within the context of a larger cultural accommodation model that asserts the importance of collaborating with the local ethnic minority community prior to initiating the intervention phase of a clinical research program.

The family theme highlighted the importance of connecting Latino families to their adolescent’s substance abuse treatment program. This theme supports the notion that Latino families exhibit the value of familismo which is described as the strong and loyal attachment to family members and a strong sense of caring for the health of the family (Freeman et al., 2002; Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Marin, 1987). Treatment programs that do not effectively engage families may be problematic because they do not allow Latino parents to fully support their children in treatment or in maintaining gains after treatment is completed. Further, familismo may conflict with the emphasis that many treatment models place on working primarily with the adolescent; however, Latino families may perceive their son or daughter’s substance abuse problem in relation to its effect on the entire family (Griffith, Joe, Chatham, & Simpson, 1998). Findings from the current study suggest that some level of parent education and socialization is necessary to promote collaboration between families and treatment providers. One of the ways clinical research programs can overcome these issues is to increase contact with parents by engaging in more face-to-face meetings, phone calls and mailings. These types of efforts can go a long way in increasing the social validity of the program from the perspective of ethnic minority participants (Freeman et al., 2002; Lau, 2006).

It is well known that the process of acculturation is a major influence on the development of Latino adolescents (De La Rosa, Vega, & Radisch, 2000; Vega & Gil, 1998). One consistently identified challenge related to acculturation was the differential English language proficiency experienced between adolescents and their parents. In many situations, this difference in language proficiency can lead to the adolescent translating for a parent (also known as language brokering) and may place increased stress on the adolescent (Martinez, McClure, & Eddy, 2009; Morales & Hanson, 2005; Weisskirch, 2007). In particular, Latino parents who reside in the U.S. and do not speak English face many challenges supporting their children in the juvenile justice, treatment and educational systems and this often serves to increase the stress and responsibility and stress for the adolescent (Martinez et al., 2009). The stress associated with the process of acculturation, termed acculturative stress, can have deleterious effects on adolescents such as a negative self-concept and low perceived self-efficacy for coping which places them at higher risk for substance abuse (Vega & Gil, 1999). One way this cultural issue can be addressed by clinical research programs is to infuse content into manuals that normalizes the experiences of acculturative stress for Latino adolescents while simultaneously teaching functional skills to effectively cope with it.

Ethnic identity is generally defined as how an individual identifies with his/her own cultural group (Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Phinney, 1990). The process of identity development occurs in large part during adolescence with certain aspects likely occurring universally across all racial and ethnic groups (Erikson, 1997; Phinney, 1990). However, identity development for Latino adolescents is further complicated by the process of acculturation and the related perceptions of themselves in relation to larger society. Individuals from ethnic minority groups can experience marginalization due to factors such as discrimination and oppression from the dominant culture (M. Bernal & Knight, 1994; Phinney, 1990). In the present study, participants voiced concerns about the perceived lack of identity and confusion experienced by Latino adolescents and a desire to infuse ethnic pride. For adolescents, there is evidence to suggest a link between a positive ethnic identity, connection to a cultural community and decreased risk for substance use (Brook, Whiteman, Balka, Win, & Gursen, 1998; Castro & Alarcon, 2002; Felix-Ortiz & Newcomb, 1995). Enhancement of ethnic identity for Latino adolescents is an important topic that should receive more attention by the developers of clinical research programs. Some suggestions for addressing this issue with Latino adolescents involve designing interventions that assist them in becoming aware of personal strengths as well as teaching skills to challenge negative internalized messages based on experiences of racism and discrimination.

Participants in this study also provided important insights regarding their perceptions of treatment as well as barriers to accessing it. First, Latino adolescents and their parents wanted more factual information and less rhetoric about drugs of abuse and their effects on the brain and body. Second, participants perceived that many substance abuse treatment programs lacked culturally sensitive programs or culturally competent staff. Finally, the major barriers identified in accessing treatment were cost, convenience of scheduling and a general lack of accommodations made for Latino families. Language barriers were a consistent thread across focus groups that pose a significant obstacle to many Latino families seeking substance abuse treatment for their children. Many of the barriers to treatment identified in this study are not inconsistent with barriers identified in prior research with ethnic minority participants in general (Miranda et al., 1996) and Latinos in particular (Freeman et al., 2002). These types of barriers most likely contribute to the underutilization of mental health treatment by ethnic minorities (Sue, 1977; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991) and limited representation compared to Whites in the clinical research literature (Hall, 2001; Huey & Polo, 2008; Miranda et al., 2005). Developers of clinical research programs should address potential barriers to participation when trying to recruit ethnic minority participants. Some of the suggestions for mitigating barriers to treatment for Latino families include employing bilingual staff with prior experience working with Latino families, scheduling at the convenience of the families, trouble-shooting transportation issues and conducting treatment in a central community location that is accessible and welcoming to adolescents and their families.

One of the key issues that researchers struggle with is how to integrate culturally relevant variables, like those presented in this paper, into empirically-supported treatments. For the present study, the cultural accommodation model described above was developed to address issues related to the lack of available models in the substance abuse treatment literature. This model was illustrated within the context of working with Latino adolescents and their families; however, this model could also be useful when working with other ethnic minority groups. Further refinement and model testing will be the focus of future papers.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations for the current study included a relatively small sample size within participant group categories and sampling from only one geographical region with the majority of Latinos being of Mexican descent. Larger samples from other geographical regions in the U.S. may produce different results due to regional and cultural differences and should be a focus of future research. It was also unclear how many adolescents in the present study had direct experience with substance abuse treatment although underreporting was present. Future research should include focus groups of adolescent participants at different points on the substance abuse intervention continuum such as prior to treatment, during treatment and post-treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number K23DA019914 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to thank Drs. James Alexander (University of Utah), Glen Hanson (University of Utah) and Stephen Tiffany (SUNY-Buffalo) for their assistance with this research as well as all members of the VIDA Research Team at the University of Utah.

Footnotes

The term “empirically-supported treatment” has been adopted for this paper instead of other frequently used terms (e.g., evidence-based treatments) based on the definitions provided in Whaley & Davis, 2007.

This program of research is the focus of a K23 research and career development grant awarded to the first author from the National Institute on Drug Abuse that is being carried out with the mentorship of five senior scientists in the addictions field.

References

- Bernal G, Jimenez-Chafey M, Rodriguez M. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(4):361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Saez-Santiago E. Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(2):121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M, Knight G. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Balka EB, Win PT, Gursen MD. Drug use among Puerto Ricans: Ethnic identity as a protective factor. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Kim S, Pinedo TM, Miller IW. Developing a culturally appropriate depression prevention program: The Family Coping Skills Program. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11(2):99–112. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Alarcon EH. Integrating cultural variables into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. Journal of Drug Issues. 2002;32:783–810. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Garfinkle J. Critical issues in the development of culturally relevant substance abuse treatments for specific minority groups. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1381–1388. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080207.99057.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Vega R, Radisch MA. The role of acculturation in the substance abuse behavior of African-American and Latino adolescents: Advances, issues, and recommendations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(1):33–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Rollock D, Prinz RJ, Hops H, Blechman EA. Cultural sensitivity: Problems and solutions in applied and preventive intervention. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1999;8:175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. The Life Cycle Completed. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz M, Newcomb MD. Cultural identity and drug use among Latino and Latina adolescents. In: Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Orlandi MA, editors. Drug abuse prevention with multiethnic youth. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RC, Lewis YP, Colon HM. Handbook for Conducting Drug Abuse Research with Hispanic Populations. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Tubman JG, Wagner EF. Substance abuse interventions with Latino adolescents: A cultural framework. Innovations in Adolescent Substance Abuse Interventions. 2001:353–378. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: Empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) Project. Addiction. 2004;99(2):140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Joe GW, Chatham LR, Simpson DD. The development and validation of a simpatia scale for Hispanics entering drug treatment. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:468–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GC. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Polo AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):262–301. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Caryn B, Sussman J, Rounsaville BJ. Psychotherapies for adolescent substance abusers: A pilot study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186(11):684–690. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Pyschology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL. Cultural accommodation as method and metaphor. American Psychologist. 2007:916–927. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C, McClure H, Eddy J. Language brokering contexts and behavioral and emotional adjustment among Latino parents and adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):71–98. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, Munoz RF, Lieberman A. Recruiting and retaining low-income Latinos in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:868–874. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang WC, LaFromboise T. State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales A, Hanson W. Language brokering: An integrative review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27(4):471–503. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescence and adulthood: A review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage 1. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;18(2):133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin BV. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Mena MP, Suarez-Morales L. Using treatment development methods to enhance the family-based treatment of Hispanic adolescents. In: Liddle HA, Rowe CL, editors. Adolescent Substance Abuse: Research and Clinical Advances. Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 449–470. [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R. Reliability of adolescent self-reported pretreatment alcohol and other drug use. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(4):425–434. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Community mental health services to minority groups: Some optimism, some pessimision. American Psychologist. 1977;32:616–624. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.32.8.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu LT, Takeuchi DT, Zane NWS. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. Drug Use and Ethnicity in Early Adolescence. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. A model for explaining drug use behavior among Hispanic adolescents. In: Rosa MDL, Segal B, Lopez R, editors. Conducting Drug Abuse Research with Minority Populations: Advances and Issues. The Haworth Press, Inc; 1999. pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Rodriguez YL, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. The role of acculturation, parenting, and family in Hispanic/Latino adolescent substance use: Findings from a qualitative analysis. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7(3):304–327. doi: 10.1080/15332640802313320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskirch R. Feelings about language brokering and family relations among Mexican American early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27(4):545–561. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL, Davis KE. Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health services. American Psychologist. 2007;62(6):563–574. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Assessing adolescent substance use problems and other areas of functioning: State of the art. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 80–108. [Google Scholar]