Abstract

The objective was to measure the presence of any interaction between the effect of mobile covert speed camera enforcement and the effect of intensive mass media road safety publicity with speed-related themes. During 1999, the Victoria Police varied the levels of speed camera activity substantially in four Melbourne police districts according to a systematic plan. Camera hours were increased or reduced by 50% or 100% in respective districts for a month at a time, during months when speed-related publicity was present and during months when it was absent. Monthly frequencies of casualty crashes, and their severe injury outcome, in each district during 1996–2000 were analysed to test the effects of the enforcement, publicity and their interaction. Reductions in crash frequency were associated monotonically with increasing levels of speed camera ticketing, and there was a statistically significant 41% reduction in fatal crash outcome associated with very high camera activity. High publicity awareness was associated with 12% reduction in crash frequency. The interaction between the enforcement and publicity was not statistically significant.

The Transport Accident Commission (TAC) and the Victoria Police work together to ensure that road safety advertising campaigns and enforcement programs are coordinated, often with enforcement and advertising programs targeting similar high-risk behaviours.

In the area of speeding, the combined effect of enforcement and publicity may be simply additive, or potentially synergistic where the combined effect may be larger than expected given the effect of either program on its own.

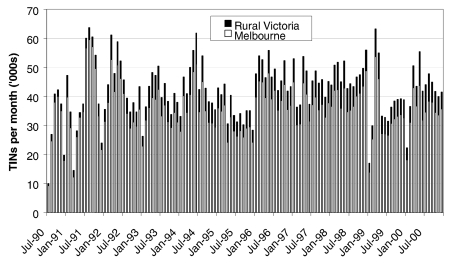

A program of covertly-operated, car-mounted speed camera enforcement has operated in Victoria since 1990. The operational hours were increased to 4000 hours per month and remained at that level during 1992–2000, covering over 4,000 sites throughout the state. The number of Traffic Infringement Notices (TINs) issued for speeding offences detected by the cameras has averaged around 42,000 per month during the period (Figure 1). Given that the state population has been around 4.5 million, this is a very high level of ticketing using an automatic surveillance method.

Fig. 1.

TINs issued from speeding offences detected by cameras

Since late 1989, the TAC has undertaken intensive road safety publicity in the mass media, principally using television advertising. The exposure of television advertising is measured by Target Audience Rating Points (TARPs), the summation of the estimated percentage of persons in the viewing area watching at the time each advertisement appeared. The recall of television advertising has been shown to decay exponentially with time. “Adstock” measures the impact of past and current levels of TARPs, based on an exponential decay function [Broadbent 1979], and has been shown to be correlated with the audience awareness of TAC advertisements [Cameron, Haworth, Oxley et al 1993].

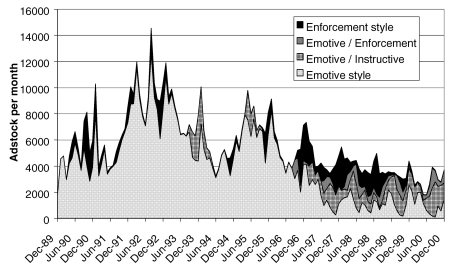

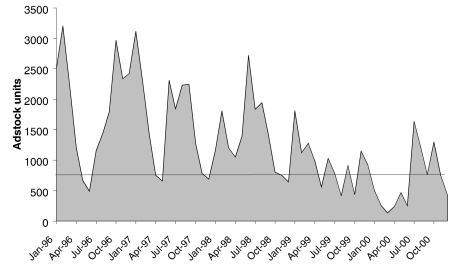

During the initial years, the TAC advertisements principally used emotive styles to convey road safety messages, but from the mid-1990s a greater proportion of the publicity used non-emotive styles to promote enforcement-related messages (Figure 2). Typical emotive-style messages aimed to instill fear of killing or seriously injuring a loved one or innocent child, whereas the enforcement messages emphasised the risk of detection for key traffic offences.

Fig. 2.

Adstock of road safety television advertising in Victoria

It was considered important to understand how the mobile covert speed camera enforcement and speed-related TAC publicity interact, specifically in relation to their effect on the risk of casualty crashes and the injury severity of the crash outcomes. The study also aimed to determine whether varying the levels and co-presentation of publicity and enforcement resulted in a change in perception of the level of speed enforcement and TAC advertising, and whether there was a change in the perceived risk of being caught when speeding.

Previous research has indicated that the speed camera program conducted by the Police and the road safety publicity program conducted by the TAC are individually linked to reductions in crashes [Cameron, Cavallo and Gilbert, 1992; Cameron et al, 1993; Cameron and Newstead, 2000]. However, little is understood about the interaction between these two programs.

METHOD

During 1999, speed camera hours were planned to increase in two Melbourne Police Districts, by either 50% or 100% for a month at a time, during two selected months when TAC speed-related publicity was present and two months when it was absent. The study design had not intended that there be enforcement reductions. However, due to resource constraints, the Police decided to reduce the speed camera operations in two other Melbourne districts during the same months, by either 50% or 100% as necessary (Table 1).

Table 1.

Schedule of changes in speed camera hours in Melbourne Police Districts compared with presence of speed-related publicity

| MONTH DURING 1999 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police District | J | F | M | April Publicity absent | M | June Publicity present | J | August Publicity absent | S | O | Nov. Publicity present | D |

| E | +100% | +50% | +50% | +100% | ||||||||

| I | +50% | +100% | +100% | +50% | ||||||||

| C | −100% | −50% | −50% | −100% | ||||||||

| H | −50% | −100% | −100% | −50% | ||||||||

| Others | no change | no change | no change | no change | ||||||||

CRASH ANALYSIS

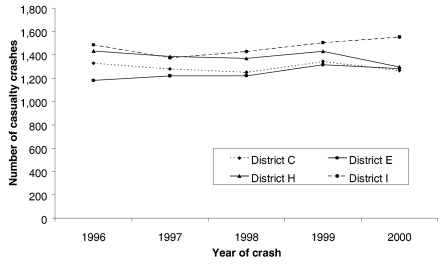

A preliminary analysis examined the direct effects of the changed levels of speed camera hours during the months in 1999 when these changes occurred. Only the four months when speed camera enforcement conditions had been changed were considered. This analysis ignored substantial crash data and will not be further described here [Cameron, Newstead, Diamantopoulou et al, 2003]. The annual number of casualty crashes in each Police District was about 1200–1600 (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Annual casualty crashes in the four Police Districts

The principal crash analysis took into account crash data from all of the months of the period 1996–2000, thus providing a more sensitive test of the presence of enforcement and publicity effects and their interaction. This analysis also included Police District, seasonality, and year-level components, thereby offering a better explanation of the crash variations and increasing the sensitivity of the tests. The aim was to develop models of monthly casualty crash frequencies, and monthly crash injury severity levels, for each Melbourne Police District as functions of the level of speed camera enforcement and the level of speed-related TAC advertising achieved per month, and the interaction between these two input factors. By doing this, the statistical significance of the interaction, and each of the main factors, was tested. The injury severity of the casualty crashes was used as a second criterion because the risk of severe injury outcome is known to increase with speed [Nilsson, 1984].

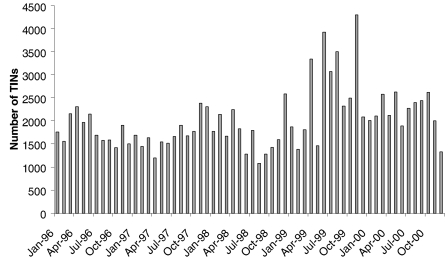

The analysis represented the enforcement impact level by the number of speeding Traffic Infringement Notices (TINs) from offences detected by speed cameras in the same district during the previous month. Previous research on the mobile covert speed cameras in Victoria had identified that their principal influence on crashes is through drivers receiving the speeding TINs from camera activity [Cameron, Newstead and Gantzer, 1995]. The TINs are typically received 7–14 days after the camera session, and the effects commence from that date for up to three weeks. Thus, substantial effects were expected in each district during the month following the changed camera hours, with the magnitude of the effect being related to the number of speeding TINs, not necessarily the number of hours. Monthly TINs were classified into five levels for analysis: very high (more than 30% greater than average for the district), high (10–30% above average), medium (within 10% of average), low (10–30% below average) and very low (more than 30% below average). There was substantial variation in monthly TINs, shown for example by the variation in District E during 1996–2000 (Figure 4).

Fig. 4.

Speeding TINs detected by speed cameras in District E

The analysis represented the advertising impact level by the Adstock of television TARPs in previous weeks. Adstock was based on an exponential decay function using a half-life of 5 weeks, which previous research has shown to be linked with serious crashes [Cameron et al, 1993]. The influence of TAC advertising (measured by Adstock) was considered in three different ways, namely:

speed-related advertising (all styles)

speed-related enforcement-style advertising

speed-related emotive-style advertising.

Each type of Adstock was categorised as high or low level in the month, as illustrated in Figure 5 for all styles of speed-related advertising using a boundary of 750 Adstock units per month. The enforcement-style and emotive-style advertising awareness was classified as high or low level using boundaries of 300 and 500 Adstock units, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Speed-related television advertising Adstock per month

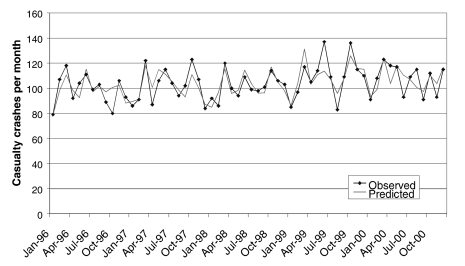

The analysis made few assumptions about the relationships between crash outcomes and the explanatory factors, especially the functional forms of the relationships. Two statistical techniques belonging to the Generalised Linear Modelling family were used to analyse the effect of the enforcement and advertising on crash outcomes during 1996–2000. The first was Poisson Regression, to determine the effect on casualty crash frequency, and the second was Logistic Regression, to determine the effect on the injury severity of the casualty crashes. Each model was fitted to the monthly crash outcome (frequency, or injury severity level) in all Melbourne Police Districts and all months of 1996–2000 together, and was shown to fit the data adequately [Cameron et al, 2003]. A comparison of the crash frequencies predicted by the Poisson Regression model and the actual crashes in District E is shown in Figure 6.

Fig. 6.

Poisson Regression fit to the casualty crashes in District E

SURVEYS OF DRIVER PERCEPTIONS

Telephone surveys of drivers’ awareness of the enforcement increases and publicity presence were conducted in each of the Police Districts in which speed camera activity had been increased in 1999, during the month of increase. A survey conducted prior to the first enforcement period acted as a baseline for comparison. The surveys were conducted at the end of each relevant month.

The survey design had assumed that the effects of the increased enforcement could be observed in surveys conducted at the end of months in which these changes occurred. The timing of the surveys was such that drivers were unlikely to have perceived the increase in speed camera activity, by either the receipt of one or more speeding TINs or knowledge of other drivers who had. The covert nature of speed camera operations would have minimised the perception through direct observation. For related reasons, the surveys were unable to provide evidence of the presence or absence of an interaction between the effects of the enforcement increase and the publicity presence. However, the survey results were able to measure the effect of the speed-related publicity on the ratings of the perceived risk of detection for speeding.

RESULTS

CRASH OUTCOMES

The results from Poisson Regression analysis of monthly casualty crash frequency are interpretable as the estimated percentage change associated with the level of the factor (enforcement, publicity or their interaction), relative to the crash frequency in the reference level. The analysis allowed 95% confidence limits to be calculated for each estimated percentage change in crashes. Medium level of enforcement, and Low level of publicity awareness, were defined as the reference levels when assessing the main effects of these factors. The estimated percentage changes associated with the interaction levels need to be interpreted in conjunction with the main effect estimates. The reference levels for the interaction were those where either the enforcement or publicity factor were at their reference level.

The results from the Logistic Regression of the injury severity of the monthly casualty crashes are interpretable as estimated odds ratios (or relative risk of severe injury outcome) associated with the level of the factor, relative to the risk at the reference level (set equal to 1.0). The reference levels of the two factors and their interaction were the same as those used in the Poisson Regression of casualty crash frequency. Two measures of injury severity were used in parallel analyses: (i) proportion of casualty crashes resulting in fatal outcome, and (ii) proportion resulting in fatal or serious injury (usually hospital admitted) outcome. The risk of fatal or serious injury outcome combined appeared less sensitive to the effects of the enforcement and publicity, compared with the risk of fatal outcome alone, and hence these results will not be reported here [Cameron et al, 2003].

Casualty crash frequencies

Table 2 shows the estimated percentage changes in crashes, their 95% confidence limits, and the statistical significance test of each estimate associated with the enforcement and publicity levels and their interaction. The estimates associated with the Police Districts, month, year and their interactions are not presented because they are not relevant to the tests for the presence of enforcement and publicity effects.

Table 2.

Estimated effects on casualty crashes of levels of speed camera enforcement, awareness of speed-related publicity, and their interaction

| Parameter | d.f. | Percent Change | Conf. Limits | Chi-Square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Enforcement | ||||||

| Very Low | 1 | 6.82 | −1.63 | 15.99 | 2.46 | 0.116 |

| Low | 1 | 3.62 | −2.10 | 9.67 | 1.51 | 0.220 |

| High | 1 | −2.11 | −7.21 | 3.27 | 0.61 | 0.435 |

| Very High | 1 | −3.00 | −8.23 | 2.52 | 1.17 | 0.280 |

| Medium | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| Publicity | ||||||

| High | 1 | −12.20 | −22.62 | −0.39 | 4.08 | 0.043 |

| Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Enforcement * Publicity | ||||||

| Very Low * High | 1 | −4.35 | −12.46 | 4.50 | 0.97 | 0.324 |

| Very Low * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| Low * High | 1 | −1.29 | −7.54 | 5.38 | 0.15 | 0.697 |

| Low * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| High * High | 1 | 2.01 | −4.37 | 8.83 | 0.37 | 0.546 |

| High * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| Very High * High | 1 | 3.63 | −3.35 | 11.14 | 1 | 0.316 |

| Very High * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| Average * High | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

| Average * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | ||

A global test of the statistical significance of the interaction coefficients was undertaken by examining the increase in scaled deviance when the enforcement by publicity interaction was removed from the model. The increase in deviance was 3.42 on 4 d.f., which was not statistically significant (p = 0.490). None of the four interaction coefficients were individually statistically significant (Table 2). While not significant, the signs and magnitudes of the interaction coefficients were consistent with negative synergy, i.e. when high enforcement and high publicity awareness operated together, their combined effect was less than expected from their individual effects.

A global test of the enforcement coefficients was also performed by examining the increase in scaled deviance when the enforcement factor was removed from the reduced model above. The increase was 6.53 on 4 d.f., which was not statistically significant, but marginally so (p = 0.163). None of the enforcement coefficients were individually significant. However, their monotonic pattern of estimated effects was consistent with the expected enforcement effect, decreasing from an estimated 6.8% increase in casualty crashes associated with very low levels of enforcement, to a 3.0% decrease in crashes with very high levels of enforcement.

The coefficient of the publicity factor was statistically significant (p = 0.043) and, being dichotomous, this factor did not require a global test. High levels of speed-related advertising awareness were associated with a 12.2% reduction in casualty crashes, relative to the effect at low levels of awareness.

Injury severity of casualty crashes

Table 3 shows the Logistic Regression results for crash injury severity measured by the fatality rate, i.e. the proportion of casualty crashes resulting in fatal outcome. The odds ratio approximately measures the estimated relative risk that the casualty crash outcome will be fatal under the particular enforcement or publicity condition (because the absolute fatality risk is small) relative to the risk in the reference category.

Table 3.

Estimated risks of fatal outcome of casualty crashes associated with levels of speed camera enforcement, awareness of speed-related publicity, and their interaction

| Parameter | d.f. | Odds Ratio | Conf. Limits | Chi-Square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Enforcement | ||||||

| Very Low | 1 | 1.44 | 0.77 | 2.70 | 1.29 | 0.255 |

| Low | 1 | 0.94 | 0.60 | 1.49 | 0.06 | 0.803 |

| High | 1 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.49 | 0.03 | 0.872 |

| Very High | 1 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 4.47 | 0.035 |

| Medium | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Publicity | ||||||

| High | 1 | 1.80 | 0.60 | 5.36 | 1.10 | 0.294 |

| Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Enforcement * Publicity | ||||||

| Very Low * High | 1 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 1.36 | 1.16 | 0.281 |

| Very Low * Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Low * High | 1 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 1.57 | 0.08 | 0.775 |

| Low * Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| High * High | 1 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 1.56 | 0.09 | 0.768 |

| High * Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Very High * High | 1 | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.83 | 1.88 | 0.171 |

| Very High * Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Average * High | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Average * Low | 0 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

Neither the enforcement by publicity interaction, nor the publicity awareness level, had a statistically significant effect on the fatality rate. Hence, while there are some apparently quite substantial departures in relative risk from 1.0 for these two factors, there is no reliable evidence that these effects are real and not due to chance.

In contrast, the level of speed camera enforcement was statistically significantly associated with the fatality rate. The relative risk of 0.59 associated with very high level of enforcement was individually statistically significantly different from 1.0 (p = 0.035), suggesting that the risk of fatal casualty crash outcome associated with speed camera offence detections at this level is 41% less than expected compared with medium levels of enforcement. The relative risk appears to range from 1.44 associated with very low levels of enforcement to 0.59 associated with very high levels.

Style of speed-related advertising

During 1996–2000, the style of TAC’s speed-related advertising was generally either emotive, or non-emotive with enforcement-related messages. The analysis of casualty crash frequencies was repeated with only the emotive-style publicity and then the enforcement-style publicity considered in the analysis. Table 4 shows the Poisson Regression results when the emotive-style publicity awareness was considered.

Table 4.

Estimated effects on casualty crashes of levels of speed camera enforcement, awareness of emotive-style speed-related publicity, and their interaction

| Parameter | d.f. | Percent Change | Conf. Limits | Chi-Square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Enforcement | ||||||

| Very Low | 1 | 5.92 | −0.89 | 13.20 | 2.88 | 0.090 |

| Low | 1 | 2.46 | −2.57 | 7.75 | 0.9 | 0.344 |

| High | 1 | −2.16 | −7.08 | 3.04 | 0.68 | 0.409 |

| Very High | 1 | −3.48 | −8.66 | 2.00 | 1.58 | 0.209 |

| Medium | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Publicity | ||||||

| High | 1 | −12.62 | −22.97 | −0.88 | 4.4 | 0.036 |

| Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Enforcement * Publicity | ||||||

| Very Low * High | 1 | −3.62 | −10.60 | 3.88 | 0.93 | 0.335 |

| Very Low * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Low * High | 1 | 0.16 | −5.76 | 6.44 | 0 | 0.960 |

| Low * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| High * High | 1 | 2.03 | −4.42 | 8.92 | 0.36 | 0.547 |

| High * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Very High * High | 1 | 4.28 | −2.81 | 11.88 | 1.36 | 0.243 |

| Very High * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Average * High | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| Average * Low | 0 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

The results were similar to those in Table 2 where all styles of speed-related publicity were considered. The global tests of the statistical significance of the enforcement by publicity interaction and of the enforcement factor were not statistically significant. However, the monotonic pattern of estimated enforcement effects was retained, as in Table 2. The coefficient of the publicity factor was statistically significant (p = 0.036), suggesting that high levels emotive-style advertising were associated with a 12.6% reduction in casualty crashes, relative to effects at low levels of awareness of this type of speed-related publicity.

The Poisson Regression analysis of casualty crashes when the enforcement-style publicity was considered was not satisfactory, producing inconsistent and apparently artifactual results [Cameron et al, 2003]. However the results for enforcement-style publicity and those in Table 4 suggested that the apparent effect of the speed-related publicity estimated in Table 2 was predominantly due to the advertising with emotive styles.

DRIVER PERCEPTIONS

The survey results were able to provide information on the effects of the speed-related publicity during 1999 on drivers’ perceptions of the risk of detection if speeding 15 km/h over the speed limit. The perceived risk of detection was measured on an 11-point rating scale ranging from 0 (“would never happen”) to 10 (“certain to happen”).

Surveys carried out in months with speed-related advertising, in comparison with surveys in months without, were intended to measure the effects of the publicity presence on driver perceptions. In practice, one of the two months without publicity was contaminated by a high level of awareness, measured by Adstock, of speed-related advertising in earlier months. Thus the ratings of driver perceptions during these months were considered to measure the average of perceptions under conditions of high and low publicity awareness (or medium level of awareness). The surveys during the months with speed-related advertising present reflected high levels of awareness.

Table 5 shows the differences in driver perceptions, under the two levels of awareness of speed-related publicity, of eight different risks of detection related to themselves, other drivers, different speed limit zones, and times of day. In six of the eight contrasts, there was a statistically significant (p < 0.03) increase in the perceived risk associated with the publicity awareness being at high levels. A nonstandard significance level (p = 0.03) was used because of concern about the multiple number of comparisons made in Table 5.

Table 5.

Average ratings of the perceived risk of detection if speeding 15 km/h over the speed limit

| Level of awareness of speed-related advertising | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medium (N = 435) | High (N = 443) | |

| Risk of detection for self, 60km/h, daytime | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for self, 100km/h, daytime | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for self, 60km/h, nighttime | 3.6 | 4.1 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for self, 100km/h, nighttime | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for others, 60km/h, daytime | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for others, 100km/h, daytime | 3.6 | 4.1 |

| Significance | p<.03 | |

| Risk of detection for others, 60km/h, nighttime | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| Significance | n.s. | |

| Risk of detection for others, 100km/h, nighttime | 3.3 | 3.5 |

| Significance | n.s. | |

DISCUSSION

To a large extent the principal objective of this study was achieved, namely to examine the interaction of the effects of levels of speed camera enforcement and the effect of speed-related mass media publicity. The study was unable to find evidence of an interaction effect on casualty crash frequency. This finding applied when all styles of TAC speed-related publicity were considered and when only the emotive-style speed-related publicity was considered. The analysis could not be considered definitive in the case of enforcement-style speed-related publicity because of the unsatisfactory nature of the statistical modeling. There was also an absence of evidence of an interaction effect on the injury severity outcome of the casualty crashes when the speed-related publicity generally and the emotive-style publicity were considered.

There was weak, but not statistically significant, evidence that the level of the number of speeding tickets (TINs) detected by speed cameras in the previous month was associated with casualty crash reductions in the same Police District. The evidence is strengthened by the monotonic pattern of increased crash reductions associated with increased TIN levels, and crash increases associated with reduced TIN levels. The monotonic pattern of enforcement effects is consistent with the smooth relationship identified by Elvik (2001). This consistency of findings suggests a real effect of the speed camera enforcement on casualty crash frequency.

There was statistically significant evidence that very high levels of TINs in the previous month were associated with a reduction in the risk of fatal outcome of the casualty crashes, adding further support to the effect of the enforcement on road trauma.

There was statistically significant evidence that high levels of awareness of speed-related TAC publicity were associated with reductions in casualty crashes. This finding appeared to derive from the effect of the emotive-style speed-related publicity. There was no evidence of an effect of the emotive-style publicity, nor speed-related publicity in total, on the severity outcome of the casualty crashes. The study was generally inconclusive regarding the effects of the enforcement-style speed-related publicity. However, the results suggested that the enforcement-style publicity contributed very little to the casualty crash reductions.

The surveys of drivers’ perceptions of the risk of detection when speeding provided evidence that the perceived risk was associated with the level of awareness of the speed-related publicity in general (the separate effects of emotive- and enforcement-style could not be examined).

This finding provides some explanation for the finding that high levels of awareness of the speed-related publicity were associated with casualty crash reductions. An attitudinal shift with regard to the likelihood of being detected when speeding would seem to be a viable mechanism to explain the reduction in casualty crash risk, perhaps through a reduction in speed behaviour. The surprising finding is that the crash risk reduction was associated with the awareness of speed-related publicity with emotive style, and was apparently unrelated to the publicity with enforcement style.

This study was limited in its ability to generalise to all circumstances of speed camera operations in conjunction with speed-related publicity because of the short (one-month) period during which speed camera hours were increased (and decreased) in selected Police Districts during 1999. It is possible that, with longer periods of change in speed camera levels, drivers may have developed stronger perceptions of the increased enforcement through personal experience of receiving TINs, knowledge of other drivers who had, and perhaps even direct observation of camera operations. A longer period of change may have led to stronger effects of the presence (or absence) of the enforcement on speed behaviour and hence on crashes. The interaction of these enforcement changes with speed-related publicity may also have been different, and the interaction may have been related to the style of publicity in different ways.

CONCLUSIONS

This study of the interaction of the effects of mobile covert speed camera enforcement and intensive speed-related mass media publicity in Victoria reached the following conclusions:

There was no evidence of an interaction in the effects of the enforcement and the publicity on casualty crash frequency.

The number of speeding tickets detected by speed cameras in Melbourne Police Districts influenced the casualty crash frequency in the same district during the following month. Casualty crashes were reduced by 3.0% following months with very high levels of speeding tickets (more than 30% greater than average) and increased by 6.8% following months with very low levels of speeding tickets (more than 30% lower than average).

The risk of fatal outcome of the casualty crashes was also related to the number of speeding tickets detected in the District during the previous month. The risk of fatal outcome was reduced by 41% following months with very high levels of speeding tickets and increased by 44% following months with very low levels of speeding tickets.

High levels of awareness of TAC speed-related publicity with emotive styles produced casualty crash reductions in Melbourne during the months in which it occurred. Casualty crashes were reduced by 12–13% when awareness, measured by the Adstock of television advertising levels, of emotive-style speed-related publicity exceeded 500 Adstock units, compared with effects during lower levels of awareness of the publicity.

There was no evidence of an effect of the emotive-style speed-related publicity on the injury severity outcome of the crashes.

There was no evidence that awareness of the speed-related publicity with enforcement styles contributed to casualty crash reductions during 1996–2000.

Drivers’ perceptions of the risk of detection when speeding was increased by high levels of awareness of the speed-related publicity, compared with the perception when the awareness was at medium levels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The survey of driver perceptions was carried out and analysed by Warren Harrison and Emma Fitzgerald while members of staff of the Monash University Accident Research Centre. The interpretation of the survey results is that of the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- Broadbent S. One way TV advertisements work. Journal of the Market Research Society. 1979;21(3):139–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, Cavallo A, Gilbert A. Crash-based evaluation of the speed camera program in Victoria 1990–1991. Phase 1: General effects. Phase 2: Effects of program mechanisms (Report No. 42) Melbourne: Monash University Accident Research Centre; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, Haworth N, Oxley J, Newstead S, Le T. Evaluation of Transport Accident Commission road safety television advertising (Report No. 52) Melbourne: Monash University Accident Research Centre; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, Newstead S. Response by Monash University Accident Research Centre to “Re-investigation of the effectiveness of the Victorian Transport Accident Commission’s road safety advertising campaigns” (White, Walker, Glonek and Burns, 2000) (Report No. 177) Melbourne: Monash University Accident Research Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, Newstead S, Diamantopoulou K, Oxley P. The interaction between speed camera enforcement and speed-related mass media publicity in Victoria. Melbourne: Monash University Accident Research Centre; 2003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, Newstead S, Gantzer S. Effects of enforcement and supporting publicity programs in Victoria, Australia. Proceedings of the Conference: Road Safety in Europe and Strategic Highway Research Program; Prague, The Czech Republic. Sweden: National Road and Transport Research Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik R. Cost-benefit analysis of Police enforcement. Working paper 1, ESCAPE (Enhanced Safety Coming from Appropriate Police Enforcement) Project; European Union. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson G. Speeds, accident rates and personal injury consequences for different road types. Rapport 277, Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute (VTI); Sweden. 1984. [Google Scholar]