Abstract

Various studies have been done to identify antioxidants from plant sources and efforts have been taken to incorporate it in conventional therapy. In our present study, petroleum ether, ethanolic, and aqueous extracts of Rubus ellipticus fruits have been evaluated for in vitro antioxidant activity using DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power assay. BHA was used as a standard antioxidant for DPPH radical scavenging activity. The reducing power assay of extracts was carried out with ascorbic acid as a standard reducing agent. All the analysis was made with the use of UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The results of the both assay showed that all the extracts of R. ellipticus fruits possess significant free radical scavenging and reducing power properties at concentration-dependent manner. Hence, it can be concluded that the R. ellipticus fruits could be pharmaceutically exploited for antioxidant properties.

Keywords: DPPH scavenging, reducing power, Rubus ellipticus

INTRODUCTION

Free radicals are chemical species, which contain one or more unpaired electrons due to which they are highly unstable and cause damage to other molecules by extracting electrons from them in order to attain stability.[1]

Free radicals are generated as part of the body's normal metabolic process and play a dual role in our body as both deleterious and beneficial species. Excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or a decrease in antioxidant levels may lead to the tissue damage and different diseases.[2] Antioxidant plays a major role in protecting our body from disease by reducing the oxidative damage to cellular component caused by ROS.[3] Recent investigations suggest that the plant origin antioxidants with free-radical scavenging properties may have great therapeutic importance in free radical mediated diseases like diabetes, cancer, neurodegenerative disease, cardiovascular diseases, aging, gastrointestinal diseases, arthritis, and aging process. Many synthetic antioxidant compounds have shown toxic and/or mutagenic effects, while relatively plant-based medicines confer fewer side effects than the synthetic drug in some instances.[4]

The plant Rubus ellipticus (Smith) is commonly called as Indian raspberry tree and Himalayan raspberry belonging to family Rosaceae.[5,6] Different parts of the plant have been claimed to be useful in ailments like diabetes, diarrhea, gastralgia, wound healing, dysentery, antifertility, antimicrobial, analgesic, and epilepsy.[7,8]

In view of the above observation, our interest was to find out natural antioxidant from the fruits of R. ellipticus using in vitro antioxidant assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and Authentication of Plant Materials

Fruits of R. ellipticus smith were obtained from Shivam nursery and plant supplier, Etawah, UP, India, in the month of June–July 2008. The identification and authentication were done by Dr. Harish K Sharma, Ayurvedic Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka, India. A voucher specimen (No. AO-101) has been submitted in herbarium department of Sir Madanlal Institute of Pharmacy, Etawah, UP, India, for future reference.

Preparation of Plant Extracts

The fully ripe and shade dried fruits of R. ellipticus smith were grinded with the help of grinder and extracted successively with petroleum ether (60%), ethanol (80%), and distilled water (10 cycles). The extracts were concentrated for further studies at reduced pressure and temperature in a rotary evaporator. The dried extracts were then stored in an airtight container in refrigerator at a temperature below 10°C. The solutions of petroleum ether, ethanol, and aqueous extracts were prepared by dissolving the extracts in ethanol.

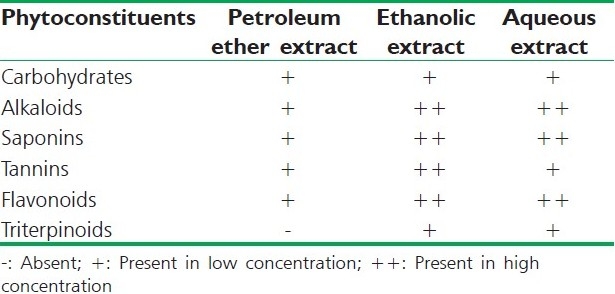

Preliminary Phytochemical Screening

The preliminary phytochemical investigation was carried out for the petroleum ether, ethanolic, and aqueous extracts of R. ellipticus fruits for the detection of phytoconstituents present. Test for the presence of common phytochemicals were carried out by standard methods [Table 1].[9]

Table 1.

Preliminary phytochemical screening of R. ellipticus fruit extracts

Chemicals and Reagents

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), BHA (butylated hydroxy anisole), ascorbic acid, potassium ferricyanide, FeCl3, tris HCl buffer, phosphate buffer, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and all other chemicals including solvents were of analytical grade and procured from Nice Chemicals Pvt. Ltd., Cochin.

Antioxidant Assay

The antioxidant activity of plant extracts was determined by different in vitro methods such as the DPPH free radical scavenging assay and reducing power methods. The different extracts were dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 50–200 mg/ml. All the assays were carried out in triplicate, and average values were considered.

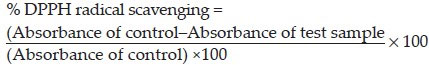

Dpph Radical Scavenging Activity

DPPH scavenging activity of the plant extracts was carried out according to the method of Koleva et al. and Mathiesen et al.[10,11] Ethanol solution of plant extracts (0.2 ml) at different concentrations (50–200 μg/ml) was mixed with 0.8 ml of tris HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4). One milliliter DPPH (500 mM in 1.0 ml ethanol) solution was added to the above mixture. The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated for 30 min in room temperature. Absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 517 nm UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Systronics 117, Japan). All the assays were carried out in triplicates. Ethyl alcoholic solution of R. ellipticus fruits (0.2 ml) were used as blank and DPPH ethanolic solution was (500 mM, 1.0 ml) served as control. The BHA was used (butylated hydroxy anisole) as a standard antioxidant in this method. Percentage of DPPH scavenging activity was determined as follows:

Decreased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates stronger DPPH radical scavenging activity. In this study, petroleum ether, ethanolic, and aqueous extracts of R. ellipticus fruits were used.

Reducing Power Assay

This was carried out as per the method of Yildrim et al. and Lu and Foo.[12,13] One milliliter of ethyl alcoholic solution of plant extracts (final concentration 100–200 mg/l) was mixed with 2.5 ml phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 2.5 ml potassium ferricyanide [K3Fe (CN)6] (10 g/l); mixture was incubated at 50°C for 20 min; 2.5 ml of trichloro acetic acid (100 g/l) was added to the mixture, which was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Finally, 2.5 ml of the supernatant solution was mixed with 2.5 ml of distilled water and 0.5 ml FeCl3 (1 g/l). Absorbance was measured at 700 nm in UV-Visible Spectrophotometer; 2.5 ml solution of ascorbic acid (concentration 5–10 mg/ml) and phosphate buffer were used as standard and control group, respectively. Ethyl alcoholic solution of plant extracts (1.0 ml) was employed as blank. Increased absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates stronger reducing power.[14]

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean±SEM of three determinants. Comparison among the groups was tested by one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preliminary phytochemical studies revealed the presence of carbohydrates, glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, and tannins in all the fruit extracts of R. ellipticus as exhibited in Table 1. In vitro antioxidant activity of the plant extracts was observed by DPPH radical scavenging assay and reducing power methods.

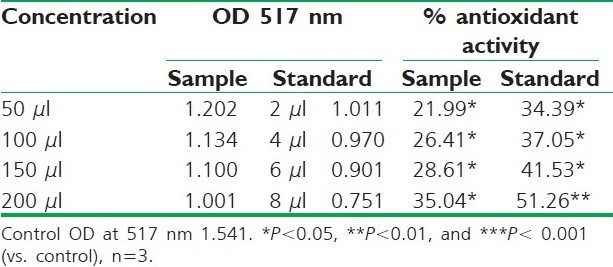

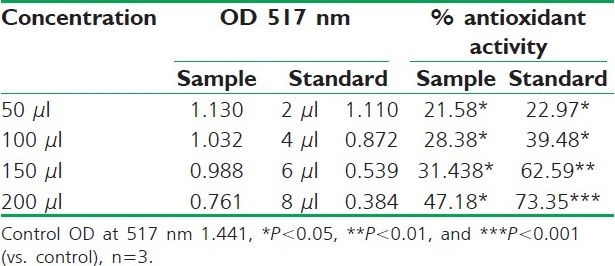

DPPH radical scavenging activity of different fruit extracts of R. ellipticus and BHA is presented in Tables 2–4. Reducing powers of different fruit extracts of R. ellipticus and ascorbic acid are presented in Tables 5–7.

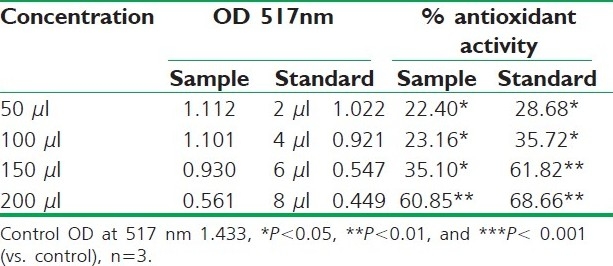

Table 2.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of petroleum ether extract of R. ellipticus fruits

Table 4.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of aqueous extract of R. ellipticus fruits

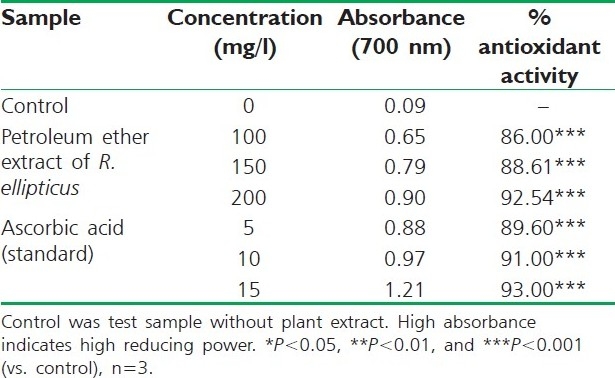

Table 5.

Reducing power of petroleum ether extract of R. ellipticus fruits

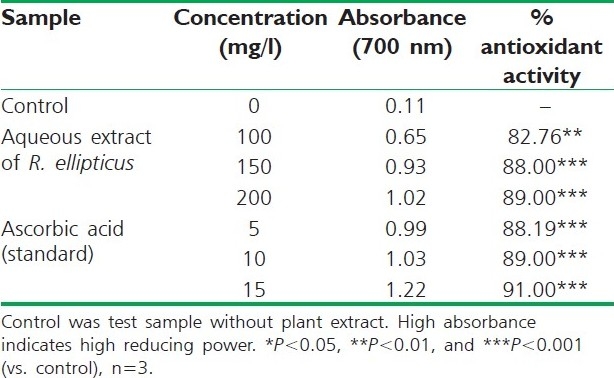

Table 7.

Reducing power of aqueous extract of R. ellipticus fruits

Table 3.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of ethanolic extract of R. ellipticus fruits

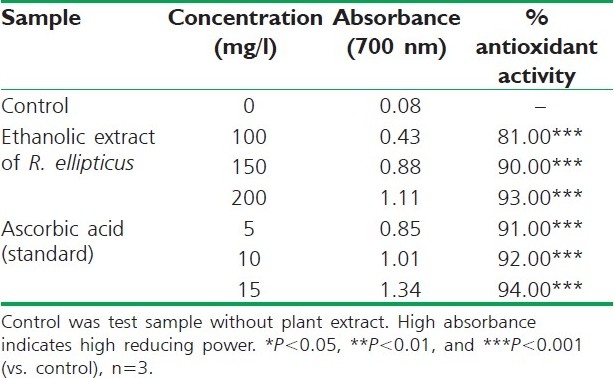

Table 6.

Reducing power of ethanolic extract of R. ellipticus fruits

Fruit extracts of R. ellipticus have got profound antioxidant activity. Both methods have proven the effectiveness of the petroleum ether, ethanolic, and aqueous extracts compared to the reference standard antioxidant BHA and ascorbic acid. The DPPH antioxidant assay is based on the ability of DPPH, a stable free radical, to decolorize in the presence of antioxidants. The DPPH radical contains an odd electron, which is responsible for the absorbance at 517 nm and also for visible deep purple color. When DPPH accepts an electron donated by an antioxidant compound, the DPPH is decolorized which can be quantitatively measured from the changes in absorbance. All the fruit extracts of R. ellipticus exhibited a significant dose-dependent inhibition of DPPH activity.

The reducing ability of a compound generally depends on the presence of reductants, which have been exhibited antioxidative potential by breaking the free radical chain, donating a hydrogen atom. The presence of reductants (i.e., antioxidants) in R. ellipticus fruit extracts causes the reduction of the Fe3+/ferricyanide complex to the ferrous form. Therefore, the Fe2+ can be monitored by measuring the formation of Perl's Prussian blue at 700 nm.[15]

The reducing power of R. ellipticus fruits extracts was significant and the power of the extract was increased with quantity of sample. This study has the similarity with previous investigation.[16] Finally all the extracts of R. ellipticus fruits exhibited significant antioxidant activities against DPPH radical scavenging activity and reducing power assay; however, activity shown by ethanolic extracts was maximum. The reported antioxidant activity may be due to the presence of phytochemicals in titled plant.[17]

CONCLUSION

On the basis of the results obtained in the present study, it is concluded that an ethanolic extract of R. ellipticus fruits, which contains large amounts of phytoconstituents (flavanoids, tannins, etc.), exhibits high scavenging and reducing power activities compared to petroleum ether and aqueous extracts. These in vitro assays indicate that this plant extract is a significant source of natural antioxidant, which might be helpful in preventing the progress of various oxidative stresses.

However, the components responsible for the antioxidative activity are currently unclear. Therefore, further investigations need to be carried out to isolate and identify the antioxidant compounds present in the plant extract. Furthermore, the in vivo antioxidant activity of this extract needs to be assessed prior to clinical use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors are highly thankful to Mr. Vivek Yadav, Chairman and Dr. Umesh Kumar Sharma, Director, Sir Madanlal Group of Institution, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh, India for providing kind support and facilities to conduct titled activity In PG Department of Pharmacology, Sir Madanlal Institute of Pharmacy, Etawah, UP, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leong CN, Tako M, Hanashiro I, Tamaki H. Antioxidant flavonoids glycosides from the leaves of Ficus pumila L. Food Chem. 2008;109:415–20. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huda AW, Munira MA, Fitrya SD, Salmah M. Antioxidant activity of Aquilaria malaccensis (Thymelaeaceae) leaves. Pharm Res. 2009;1:270–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagulendran KR, Velavan S, Mahesh R, Begum VH. In vitro antioxidant activity and total polyphenolic content of Cyperus rotundus rhizomes. E J Chem. 2007;4:440–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Wealth of India: A Dictionary of Indian Raw Material and Industrial Products. Vol. 5. New Delhi, India: Publication and Information Directrate: CSIR; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan IA, Khanum A. Ethanomedicine and Human Welfare. Vol. 3. Hyderabad, India: Ukaaz Publication; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarong T, Sewang J. Tibetan Medicinal Plants Tibetan. Vol. 5. New Delhi, India: Medical Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vadivelan R, Bhadra S, Ravi AV, Singh K, Shanish K, Elango Evaluation of anti inflammatory and membrane stabilizing property of ethanol root extract of Rubus ellipticus smith and albino rats. J Nat Remed. 2009;9(1):74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokate CK. Practical Pharmacognosy. 4th ed. New Delhi, India: Vallabh Prakashan; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koleva II, van Beek TA, Linssen JP, de Groot A, Evstatieva LN. Screening of plant extracts for antioxidant activity: A comparative study on three testing methods. Phytochem Anal. 2002;13:8–17. doi: 10.1002/pca.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathiesen L, Malterud KE, Sund RB. Antioxidant activity of fruit exudate and methylated dihydrochalcones from Myrica gale. Planta Med. 1995;61:515–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yildirim A, Mavi A, Kara AA. Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L. extracts. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:4083–9. doi: 10.1021/jf0103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Foo Y. Antioxidant activities of polyphenols from sage (Salvia officinalis) Food Chem. 2000;75:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siju EN, Rajalakshmi GR, Kavitha VP, Anju J. In Vitro antioxidant activity of Mussaenda Frondos. Int J Pharm Tech Res. 2010;2:1236–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naznin A, Hasan N. In Vitro antioxidant activity of methanolic leaves and flowers extracts of Lippia Alba. Res J Med Med Sci. 2009;4:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vadivelan P, Rajesh KR, Bhadra S, Shanish A, Elango K, Suresh B. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of root extracts of Rubus ellipticus (Smith) Hygeia. 2009;1:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganesh T, Saikat S, Chakraborty R. In vitro antioxidant activity of Meyna laxiflora seeds. Int J Chem Pharm Sci. 2010;1:5–8. [Google Scholar]