Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of dyslipidaemia is high: in 2000, approximately 25% of adults in the USA had total cholesterol greater than 6.2 mmol/L or were taking lipid-lowering medication. Primary prevention in this context is defined as long-term management of people at increased risk but with no clinically overt evidence of CVD — such as acute MI, angina, stroke, and PVD — and who have not undergone revascularisation.

Methods and outcomes

We conducted a systematic review and aimed to answer the following clinical questions: What are the effects of pharmacological cholesterol-lowering interventions in people at low risk (less than 0.6% annual CHD risk); at medium risk (0.6–1.4% annual CHD risk); and at high risk (at least 1.5% annual CHD risk)? What are the effects of reduced or modified fat diet? We searched: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library, and other important databases up to December 2009 (Clinical Evidence reviews are updated periodically, please check our website for the most up-to-date version of this review). We included harms alerts from relevant organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Results

We found 16 systematic reviews, RCTs, or observational studies that met our inclusion criteria. We performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions.

Conclusions

In this systematic review we present information relating to the effectiveness and safety of the following interventions: ezetimibe, fibrates, niacin (nicotinic acid), reduced- or modified-fat diet, resins, and statins.

Key Points

Dyslipidaemia, defined as elevated total or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, is an important risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke.

The incidence of dyslipidaemia is high: in 2000, approximately 25% of adults in the US had total cholesterol greater than 6.2 mmol/L, or were taking lipid-lowering medication.

There is a continuous, graded relationship between the total plasma cholesterol concentration and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) morbidity and mortality. IHD is the leading single cause of death in high-income countries and the second in low- and middle-income countries.

Primary prevention in this context is defined as long-term management of people at increased risk, but with no clinically overt evidence of CVD, such as MI, angina, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, and who have not undergone revascularisation.

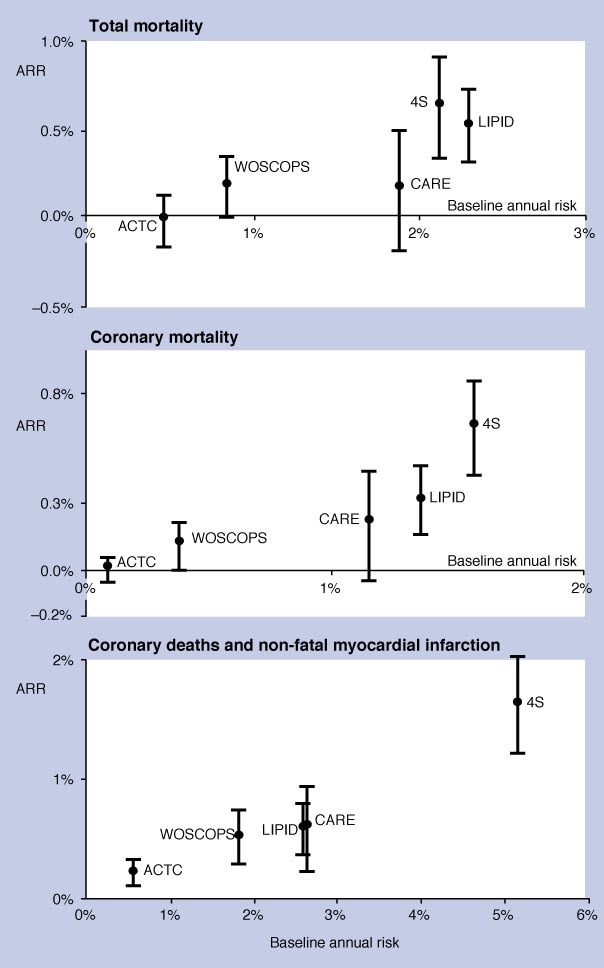

Statins have been shown to be highly effective, particularly in treating people at high risk of CHD (at least 1.5% annual risk of CHD). Although effective in people in all risk categories (low risk, medium risk), it seems that the magnitude of benefit is related to the individual's baseline risk of CHD events.

In people at medium risk of CHD (0.6–1.4% annual risk of CHD), fibrates have been shown to reduce the rate of CHD, but not of overall mortality, compared with placebo.

We don't know whether resins are beneficial in reducing non-fatal MI and CHD death in people at medium risk of CHD. We found no evidence relating to the effects of niacin (nicotinic acid) in people at medium risk of CHD.

We found no evidence that examined the efficacy of niacin, fibrates, or resins in people either at low or high risk of CHD.

We found no evidence on the effects of ezetimibe in people at low, medium, or high risk of CHD events.

A reduced- or modified-fat diet may be beneficial in reducing cardiovascular events in people at risk of CHD events.

Clinical context

About this condition

Definition

Dyslipidaemia, defined as elevated total or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, is an important risk factor for CHD and stroke (cerebrovascular disease). This review examines the evidence for treatment of dyslipidaemia for primary prevention of CHD. Primary prevention in this context is defined as long-term management of people at increased risk, but with no clinically overt evidence of CVD, such as acute MI, angina, stroke, and PVD, and who have not undergone revascularisation. Most adults at increased risk of CVD have no symptoms or obvious signs, but they may be identified by assessment of their risk factors (see aetiology/risk factors below). We have divided people with no known CVD into 3 groups: low risk (<0.6% annual CHD risk), medium risk (0.6–1.4% annual CHD risk), and high risk (1.5% or more annual CHD risk). Prevention of cerebrovascular events is discussed in detail elsewhere in Clinical Evidence (see review on stroke prevention). In the US, the preferred method to calculate CVD risk would be to use the Framingham risk equations, the best validated method from a US population.

Incidence/ Prevalence

Dyslipidaemia, defined as elevated total or LDL cholesterol, or low HDL cholesterol, is common. Data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) survey conducted in 1999–2000 found that 25% of adults had total cholesterol >6.2 mmol/L, or were taking a lipid-lowering medication. According to the World Health Report 1999, ischaemic heart disease was the leading single cause of death in the world, the leading single cause of death in high-income countries, and second only to lower respiratory tract infections in low- and middle-income countries. In 1998, it was the leading cause of death, with nearly 7.4 million estimated deaths a year in member states of the WHO, and causing the eighth highest burden of disease in the low- and middle-income countries (30.7 million disability-adjusted life years).

Aetiology/ Risk factors

Major risk factors for ischaemic vascular disease include increased age, male sex, raised LDL cholesterol, reduced HDL cholesterol, raised blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, family history of CVD, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. For many of these risk factors, including elevated LDL cholesterol, observational studies show a continuous gradient of increasing risk of CVD with increasing levels of the risk factor, with no obvious threshold level. Although, by definition, event rates are higher in high-risk people, most ischaemic vascular events that occur in the population are in people with intermediate levels of absolute risk, because there are many more of them than there are people at high risk.

Prognosis

One Scottish study found that about half of people who have an acute MI die within 28 days, and two-thirds of acute MI occur before the person reaches hospital. People with known CVD are at high risk for future ischaemic heart disease events (see review on secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiac events), as are people with diabetes (see review on diabetes: prevention of cardiovascular events). For people without known CVD, the absolute risk of ischaemic vascular events is generally lower, but varies widely. Estimates of absolute risk can be based on simple risk equations or tables. Such information may be helpful in making treatment decisions.

Aims of intervention

To reduce morbidity and mortality from CHD, with minimum adverse effects.

Outcomes

Incidence of CVD events (fatal and non-fatal ischaemic heart disease events [angina, MI, and sudden cardiac mortality], and stroke), and mortality. Where possible, we have reported cardiac mortality and CVD events as separate outcomes. Where studies report composite outcomes (e.g., morbidity and mortality), we have reported the combined data under the heading of CVD events.

Methods

Clinical Evidence search December 2009. The following databases were used to identify studies for this systematic review: Medline 1966 to December 2009, Embase 1980 to December 2009, and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4 (1966 to date of issue). An additional search within the Cochrane Library was carried out for the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA). We also searched for retractions of studies included in the review. Abstracts of the studies retrieved from the initial search were assessed by an information specialist. Selected studies were then sent to the contributor for additional assessment, using predetermined criteria to identify relevant studies. Study design criteria for inclusion in this review were: published systematic reviews of RCTs and RCTs in any language, at least single blinded (unless on dietary comparisons), and containing at least 20 individuals of whom >80% were followed up. There was no minimum length of follow-up required to include studies. We excluded all drug comparison studies described as "open", "open label", or not blinded unless blinding was impossible, but included "open" or non-blinded comparison studies on dietary interventions. We included systematic reviews of RCTs and RCTs where harms of an included intervention were studied applying the same study design criteria for inclusion as we did for benefits. In addition, we use a regular surveillance protocol to capture harms alerts from organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which are added to the reviews as required. To aid readability of the numerical data in our reviews, we round many percentages to the nearest whole number. Readers should be aware of this when relating percentages to summary statistics such as relative risks (RRs) and odds ratios (ORs). We have performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions included in this review (see table ). The categorisation of the quality of the evidence (into high, moderate, low, or very low) reflects the quality of evidence available for our chosen outcomes in our defined populations of interest. These categorisations are not necessarily a reflection of the overall methodological quality of any individual study, because the Clinical Evidence population and outcome of choice may represent only a small subset of the total outcomes reported, and population included, in any individual trial. For further details of how we perform the GRADE evaluation and the scoring system we use, please see our website (www.clinicalevidence.com).

Table 1.

GRADE evaluation of interventions for primary prevention of CVD: treating dyslipidaemia

| Important outcomes | CVD events, mortality, adverse effects | ||||||||

| Number of studies (participants) | Outcome | Comparison | Type of evidence | Quality | Consistency | Directness | Effect size | GRADE | Comment |

| What are the effects of pharmacological cholesterol-lowering interventions in people at low risk (<0.6% annual CHD risk)? | |||||||||

| 1 (7832) | CVD events | Statin plus cholesterol-lowering diet v cholesterol-lowering diet alone (low risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | –1 | 0 | Moderate | Directness point deducted for use of an active co-intervention (cholesterol-lowering diet) |

| What are the effects of pharmacological cholesterol-lowering interventions in people at medium risk (0.6–1.4% annual CHD risk)? | |||||||||

| 1 (4081) | Mortality | Fibrates v placebo (medium risk) | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for incomplete reporting of results |

| 1 (4081) | CVD events | Fibrates v placebo (medium risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 1 (3806) | CVD events | Resins v placebo (medium risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | –2 | 0 | Low | Directness points deducted for uncertainty of benefit of treatment and narrow population (only men) |

| 2 (16,960) | Mortality | Statins v placebo/usual care (medium risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | –2 | 0 | Low | Directness points deducted for one RCT not being powered to detect a difference between groups, uncertainty of benefit in one RCT (due to high rate of conversion from placebo to statin), and inclusion of some people with history of CVD in one RCT |

| 2 (16,960) | CVD events | Statins v placebo/usual care (medium risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | –2 | 0 | Low | Directness points deducted for uncertainty of benefit in one RCT (due to high rate of conversion from placebo to statin) and inclusion of some people with history of CVD in one RCT |

| What are the effects of pharmacological cholesterol-lowering interventions in people at high risk (1.5% or more annual CHD risk)? | |||||||||

| 1 (6595) | Mortality | Statins v placebo (in people at high risk) | 4 | 0 | 0 | –1 | 0 | Moderate | Directness point deducted for narrow population (only men) |

| 3 (13,263) | CVD events | Statins v placebo (in people at high risk) | 4 | –1 | 0 | –1 | 0 | Low | Quality point deducted for methodological limitations (subgroup analysis in one RCT and incomplete reporting of results in one RCT). Directness point deducted for narrow populations (only men in one RCT, and only older people in one RCT) |

| What are the effects of reduced- or modified-fat diet in people at low, medium, or high risk of CHD? | |||||||||

| At least 27 RCTs (at least 48,939) | Mortality | Reduced- or modified-fat diet v no dietary modification | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 28 RCTs (at least 48, 835) | CVD events | Reduced- or modified-fat diet v no dietary modification | 4 | 0 | –1 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Consistency point deducted for conflicting results |

Type of evidence: 4 = RCT; 2 = Observational; 1 = Non-analytical/expert opinion. Consistency: similarity of results across studies Directness: generalisability of population or outcomes Effect size: based on relative risk or odds ratio

Glossary

- High-quality evidence

Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

- Low-quality evidence

Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

- Moderate-quality evidence

Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this publication is intended for medical professionals. Categories presented in Clinical Evidence indicate a judgement about the strength of the evidence available to our contributors prior to publication and the relevant importance of benefit and harms. We rely on our contributors to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to adhere to describe accepted practices. Readers should be aware that professionals in the field may have different opinions. Because of this and regular advances in medical research we strongly recommend that readers' independently verify specified treatments and drugs including manufacturers' guidance. Also, the categories do not indicate whether a particular treatment is generally appropriate or whether it is suitable for a particular individual. Ultimately it is the readers' responsibility to make their own professional judgements, so to appropriately advise and treat their patients. To the fullest extent permitted by law, BMJ Publishing Group Limited and its editors are not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, products liability or otherwise) whether they be direct or indirect, special, incidental or consequential, resulting from the application of the information in this publication.

References

- 1.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998;97:1837–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Giles WH, et al. Serum total cholesterol concentrations and awareness, treatment, and control of hypercholesterolemia among US adults: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2000. Circulation 2003;107:2185–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The world health report 1999: making a difference. The World Health Organization. Geneva. 2000. http://www.who.int/whr2001/2001/archives/1999/en/index.htm (last accessed 28 October 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heller RF, Chinn S, Pedoe HD, et al. How well can we predict coronary heart disease? Findings of the United Kingdom heart disease prevention project. BMJ 1984;288:1409–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Morrison C, Woodward M, et al. Sex differences in myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the Scottish MONICA population of Glasgow 1985 to 1991: presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and 28-day case fatality of 3991 events in men and 1551 events in women. Circulation 1996;93:1981–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson KV, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J 1991;121:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Committee. Guidelines for the management of mildly raised blood pressure in New Zealand. Wellington Ministry of Health, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Brookhart MA, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases with statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2307–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;368:1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuno K, Nakaya N, Ohashi Y, et al. Usefulness of pravastatin in primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: analysis of the Management of Elevated Cholesterol in the Primary Prevention Group of Adult Japanese (MEGA study). Circulation 2008;117:494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Haq IU, et al. Statins for primary prevention: at what coronary risk is safety assured? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:439–446. Search date not reported. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1237–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenkanen L, Manttari M, Kovanen PT, et al. Gemfibrozil in the treatment of dyslipidemia: an 18-year mortality follow-up of the Helsinki Heart Study. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I. Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1984;251:351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998;279:1615–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT–LLT). JAMA 2002;288:2998–3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1623–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford I, Murray H, Packard CJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1477–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asselbergs FW, Diercks GF, Hillege HL, et al. Effects of fosinopril and pravastatin on cardiovascular events in subjects with microalbuminuria. Circulation 2004;110:2809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geluk CA, Asselbergs FW, Hillege HL, et al. Impact of statins in microalbuminuric subjects with metabolic syndrome; a substudy of the PREVEND Intervention Trial. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooper L, Summerbell CD, Higgins JPT, et al. Dietary fat intake and prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review. BMJ 2001;322:757–763. Search date 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hjerkinn EM, Sandvik L, Hjermann I, et al. Effect of diet intervention on long term mortality in healthy middle aged men with combined hyperlipidaemia. J Intern Med 2004;255:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, et al. Low fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease. The Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. JAMA 2006;6:655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]