Abstract

Data from two recent studies of whole-exome sequencing of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) suggests spliceosome mutations have clinical relevance. Identifying the impact of these mutations on pre-mRNA splicing and MDS pathogenesis holds promise for targeted modulation of mRNA splicing in MDS.

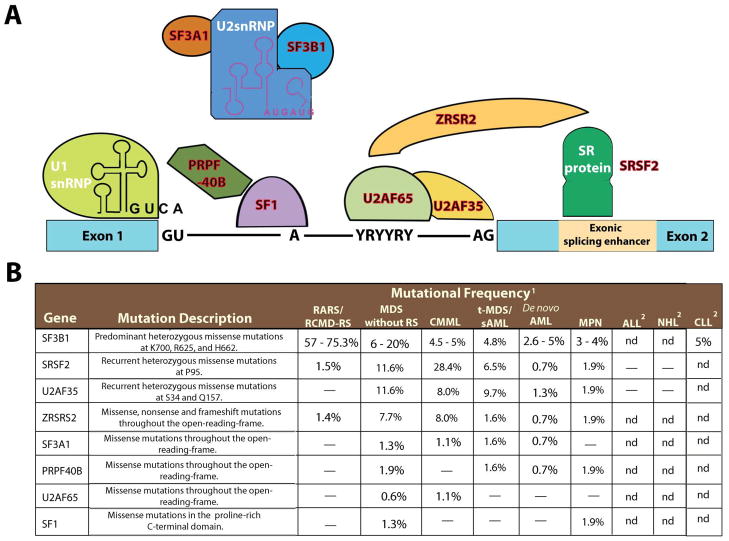

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogenous group of myeloid malignancies characterized by clonal hematopoiesis, impaired differentiation, peripheral-blood cytopenias, and increased risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Although recent studies have identified recurrent somatic mutations in most patients with MDS, approximately 20% of patients with MDS had no known somatic genetic or cytogenetic abnormalities in the largest studies to date. Two recent studies report the results of whole exome sequencing in patients with MDS (Papaemmanuil, 2011; Yoshida et al., 2011). Notably, the most frequent novel recurrent mutations found occurred in genes encoding members of the RNA splicing machinery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The spliceosome and mutations in multiple members of genes encoding spliceosomal proteins.

Five small ribonuclear protein particles (snRNPs) and over 50 accessory proteins are assembled at the exon/intron junction of pre-mRNA to form the spliceosome. The U1 snRNP binds to the 5′ splice site through base pairing between the splice site and the U1 snRNA. The branchpoint, required for the lariat intermediate, is bound by SF1 while the polypyrimidine tract is bound by the large subunit of U2AF (U2AF65). The small subunit of U2AF (U2AF35) binds to the AG at the 3′ splice site. The WW domain protein PRPF40B is thought to bind SF1 and serve in early spliceosome assembly but its functions are not well understood. Following U1 snRNP and U2AF assembly, the U2 snRNP, the U4-6 tri-snRNP and other splicing factors are assembled sequentially to form the spliceosome. SF3B1 and SF3A1 are components of U2 snRNP and it is thought that they bind pre-mRNA upstream of the intro branch site in a sequence-independent manner to anchor the U2 snRNP to pre-mRNA. Members of the serine/arginine-rich (SR) protein family bind to a nearby exonic splicing enhancer region to directly recruit splicing machinery through physical interactions with U2AF35 and ZRSR2 (a homologue of U2AF35). This interaction is critical in defining exon/intron boundaries. Members of the spliceosomal complex found to be mutated in myeloid malignancies are indicated in red in (A) and described in (B). Abbreviations: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); chronic lymphocytic luekemia (CLL); chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML); myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN); Non-hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); refaractory anemia with ring-sideroblasts (RARS); refractory-cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ring sideroblasts (RCMD-RS); ring-sideroblasts (RS); secondary AML (sAML); therapy-related MDS (t-MDS).

1“–“ indicates no mutations found and nd indicates sequencing not done.

2Only regions of recurrent mutations were sequenced in these lymphoid malignancies.

The paradigm that alterations in splicing contributes to the pathogenesis of human disease and promoting tumorigenesis is well described. However, the majority of disease-associated splicing abnormalities discovered previously were in cis-acting elements that disrupt splice-site selection at specific loci. By contrast, the Papaemmanuil et al. and Yoshida et al. reports identified mutations in the trans-acting members of the spliceosome necessary for processing pre-mRNA to mature mRNA. The genetic data supporting these mutations as disease alleles is compelling; the majority of the mutations in SF3B1 and all of the mutations in U2AF35 and SRSF2 are recurrent, heterozygous point mutations, suggesting a gain-of-function conferred by these recurrent mutations (Figure 1). In contrast, rarer mutations in ZRSR2 and PRPF40B occurred as missense or nonsense mutations, suggesting these mutations might result in loss-of-function. In addition, Yoshida et al. found that spliceosomal gene mutations are largely mutually exclusive of one another, consistent with a general role of spliceosome mutations in MDS pathogenesis.

In order to understand the spectrum of spliceosomal gene mutations, both groups also sequenced a spectrum of myeloid malignancies in addition to MDS. This data led both groups to note a striking association between SF3B1 mutations and MDS characterized by the presence of ring sideroblasts (RS). Although rare SF3B1 mutations have been reported previously in epithelial cancers derived from pancreas (Pleasance et al., 2010), breast (Wood et al., 2007), and ovary (Wood et al., 2007), SF3B1 mutations occur in the majority of patients with MDS with RS and much less commonly in other hematologic malignancies. Although mutations in the other spliceosomal components were more common in other subtypes of MDS, the mutations appear to be most enriched in myeloid malignancies with some component of dysplasia including MDS of all subtypes and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Papaemmanuil et al. noted that mutations in SF3B1 in MDS are associated with longer overall- and leukemia-free patient survival (Papaemmanuil, 2011). Given the already known favorable prognosis of MDS with RS, studies to identify whether the prognostic effect of these mutations is independent of MDS histopathologic findings are needed. Moreover, previous reports noting splicing alterations in hematologic malignancies, such as the report of frequent missplicing of GSK3β in CML (Abrahamsson et al., 2009), will need re-evaluation to determine if these cancer-specific splicing alterations result from somatic mutations in the spliceosome.

To understand the biological consequences of spliceosomal mutations in hematopoiesis, the authors overexpressed wildtype and mutant forms of U2AF35 in Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+ hematopoietic cells from wildtype mice. Competitive transplantation with similarly transduced control cells revealed a competitive disadvantage with U2AF35 mutant overexpression. Further work to characterize the effects of these mutations on other aspects of hematopoietic stem cell function including self-renewal, differentiation, and leukemogenesis are needed. Moreover, comparison of the biological effects of expression of recurrent point mutations with downregulation of expression may be very helpful in understanding the biological consequences of spliceosomal component alterations in neoplastic transformation.

The mutations in the spliceosomal complex in different myeloid malignancies suggest that these proteins may have distinct functions at different stages of hematopoietic differentiation. Very little is known about the expression of the various Serine/Arginine rich (SR) proteins in normal and malignant hematopoiesis or about the function of the spliceosome in normal hematopoietic development. Numerous splicing factors have been targeted for constitutional knockout in mice but these resulted in largely embryonic or perinatally lethality. Conditional gene-targeting in a tissue-speciifc manner has only been carried out for Srsf1 (Xu et al., 2005) and Srsf2 (Ding et al., 2004) so far. Mice with cardiac-specific deletion of Srsf1 develop severe dilated cardiomyopathy leading to death by 6–8 weeks of life while cardiac-specific Srsf2 knockout mice develop a milder cardiomyopathy and have a relatively normal life-span. These results suggest that the SR proteins fulfill specialized, non-redundant functions.

Data arguing for a role of spliceosomal components outside of pre-mRNA processing has also come from in vivo modeling. For instance, in vivo analysis of Sf3b1 knockout mice identified genetic intersection with Polycomb Group protein loss leading to the identification of multiple physical interactions between SF3B1 and members of the PRC1 complex and the BCL6 co-repressive complex (Isono et al., 2005). Further work to analyze the role of disordered PRC1 activity and BCL6 activity in MDS-RS pathogenesis are now warranted.

Yoshida et al. assessed the effects of expressing U2AF35 in wildtype and mutant forms on gene expression and showed overexpression of U2AF35 mutants led to a greater frequency of transcripts with unspliced introns and increased expression of members of the nonsense-mediated decay pathway. They concluded that U2AF35 mutations, and possibly other spliceosomal pathway mutations, function in a dominant-negative manner to inhibit normal splicing, a hypothesis requiring further evaluation. Previous studies have noted overexpression of SR family proteins in epithelial cancers, and overexpression of SR proteins (including SRSF1 and SRSF2) leads to cellular transformation ability in other cellular contexts; as such, future studies will need to dissect differences between the role of mutant and wild-type spliceosome proteins in oncogenic transformation.

Identification of splicing factor mutations in MDS may also provide a possibility for therapeutic intervention. An excellent example comes from investigational therapies for the hereditary disorder Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). DMD most commonly results from mutations in a repetitive domain of Dystrophin. Mutations in this domain can be overcome by “skipping” the mutated exon to generate truncated functional dystrophin protein. Amazingly, a strategy of delivering an antisense oligonucleotide to block an enhancer of exon splicing of the mutated exon and result in a stable mRNA transcript and dystrophin gene product has been utilized successfully in early clinical trials (van Deutekom et al., 2007). In addition, compounds that specifically target the SF3A/B subunits of U2 snRNP to result in nuclear export of intron-bearing precursors exist and should be studied further to determine if they interfere with the aberrant splicing due to recurrent mutations in these subunits (Kaida et al., 2007). These data suggest that these two studies have uncovered a novel pathway of importance to myeloid malignancies which may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for MDS patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahamsson AE, Geron I, Gotlib J, Dao KH, Barroga CF, Newton IG, Giles FJ, Durocher J, Creusot RS, Karimi M, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta missplicing contributes to leukemia stem cell generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3925–3929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900189106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JH, Xu X, Yang D, Chu PH, Dalton ND, Ye Z, Yeakley JM, Cheng H, Xiao RP, Ross J, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy caused by tissue-specific ablation of SC35 in the heart. EMBO J. 2004;23:885–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono K, Mizutani-Koseki Y, Komori T, Schmidt-Zachmann MS, Koseki H. Mammalian polycomb-mediated repression of Hox genes requires the essential spliceosomal protein Sf3b1. Genes Dev. 2005;19:536–541. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida D, Motoyoshi H, Tashiro E, Nojima T, Hagiwara M, Ishigami K, Watanabe H, Kitahara T, Yoshida T, Nakajima H, et al. Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:576–583. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, Malcovati L, Vyas P, Bowen D, Pellagatti A, Wainscoat JS, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Godfrey AL, Rapado I, Cvejic A, Rance R, McGee C, Ellis P, Mudie LJ, Stephens PJ, McLaren S, Massie CE, Tarpey PS, Varela I, Nik-Zainal S, Davies HR, Shlien A, Jones D, Raine K, Hinton J, Butler AP, Teague JW, Baxter EJ, Score J, Galli A, Della Porta MG, Travaglino E, Groves M, Tauro S, Munshi NC, Anderson KC, El-Naggar A, Fischer A, Mustonen V, Warren AJ, Cross NCP, Green AR, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Campbell PJ. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasance ED, Cheetham RK, Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Humphray SJ, Greenman CD, Varela I, Lin ML, Ordonez GR, Bignell GR, et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature08658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deutekom JC, Janson AA, Ginjaar IB, Frankhuizen WS, Aartsma-Rus A, Bremmer-Bout M, den Dunnen JT, Koop K, van der Kooi AJ, Goemans NM, et al. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2677–2686. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Yang D, Ding JH, Wang W, Chu PH, Dalton ND, Wang HY, Bermingham JR, Jr, Ye Z, Liu F, et al. ASF/SF2-regulated CaMKIIdelta alternative splicing temporally reprograms excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Cell. 2005;120:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, Nowak D, Nagata Y, Yamamoto R, Sato Y, Sato-Otsubo A, Kon A, Nagasaki M, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]