Abstract

Subventricular zone neurogenesis occurs throughout life from rodents to primates, but the existence of a rostral migratory stream of neurons in postnatal human brains is controversial. A recent report in Nature (Sanai et al., 2011) identifies two neuronal migratory streams in infant human brains targeting the olfactory bulb and prefrontal cortex.

Almost all mammalian species examined exhibit continuous neurogenesis in specific brain regions and cumulative evidence supports critical roles of newborn neurons in brain functions, including learning, memory and mood regulation (Ming and Song, 2011). Two neurogenic regions in the adult brain have been firmly established in species from rodents to primates. In the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, neural stem cells produce local glutamatergic dentate granule neurons. In the subventricular zone (SVZ), astroglial-like neural stem cells give rise to neuroblasts that migrate through the rostral migratory stream (RMS) into the olfactory bulb to become mostly GABAergic interneurons of different subtypes. In humans, postnatal dentate neurogenesis has been shown to occur across the lifespan (Eriksson et al., 1998; Knoth et al., 2010). In contrast, the presence of prominent neurogenesis and an RMS in the adult human SVZ has been under debate (Curtis et al., 2007; Sanai et al., 2004). In 2004, Sanai and colleagues reported the presence of a ribbon of Ki67+ proliferative astrocytes in the adult human SVZ that function as multipotent neural stem cells in culture (Sanai et al., 2004). They found, however, only a few proliferating cells and putative migratory βIII-tubulin+ immature neurons, and no evidence of chains of migrating neuroblasts in the SVZ or RMS to the olfactory bulb. In contrast, Curtis and colleagues reported robust cell proliferation in adult human SVZ and the presence of a migratory stream of neuroblasts along a lateral ventricular extension that connects the lateral ventricle to the olfactory bulb, based on expression of PCNA, PSA-NCAM and βIII-tubulin (Curtis et al., 2007).

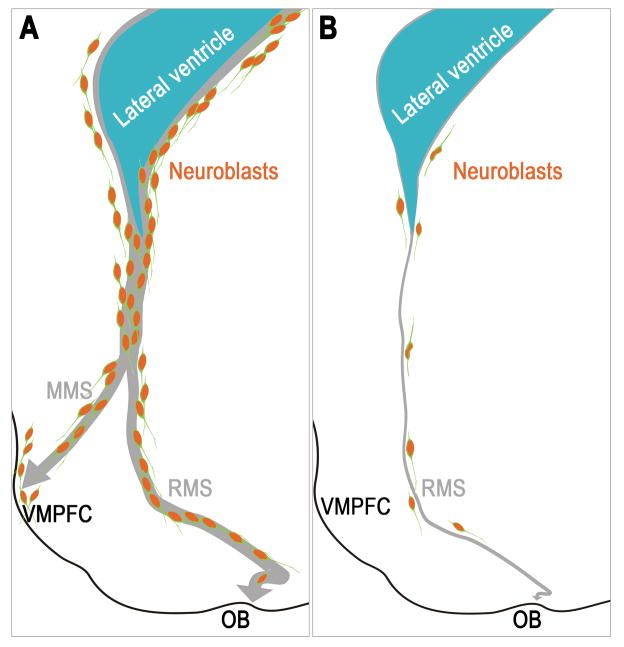

In a collaborative effort between stem cell biologists, neuropathologists and neurosurgeons, Sanai et al (2011) aimed to clarify and comprehensively characterize the landscape of neurogenesis in the human SVZ by examining neuroblast proliferation and migratory patterns in 60 postmortem human brain specimens ranging in age from birth to 84 years. First, Sanai and colleagues analyzed the distribution of putative immature migrating neurons in the SVZ of the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle and RMS in the infant human brain. They found many elongated unipolar and bipolar cells that express immature neuronal markers DCX, βIII-tubulin and PSA-NCAM in the SVZ and RMS (Figure 1A), which is consistent with recent findings from fetal human brains (Guerrero-Cazares et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). They observed many proliferating Ki67+ cells in the SVZ, some of which were also DCX+ or PSA-NCAM+. Importantly, the numbers of proliferating cells and migrating neuroblasts in the human SVZ and RMS decrease drastically from birth to 18 months of life. In adult human brains, Sanai et al. (2011) noted very few putative migrating neuroblasts in the same regions (Figure 1B), consistent with a recent report on immature neurons in the adult SVZ and RMS-like pathway (the remnant of the infant RMS) (Wang et al., 2011). Contrary to previous findings (Curtis et al., 2007), Sanai and colleagues, as well as one other recent study (Wang et al, 2011), do not report a persistent ventricular lumen connecting the adult human lateral ventricle to the olfactory bulb, although this structure appears to exist in the fetal human brain (Guerrero-Cazares et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, Sanai et al (2011) also describe the absence of this ventricular extension in the postnatal infant human brain as well. Taken together with more recent studies (Guerrero-Cazares et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011), these findings by Sanai et al (2011) rather implicate dynamic changes in human SVZ neurogenesis across lifespan, where proliferation and migration of immature SVZ and RMS neurons while robust during infancy, occur in the absence of persistent ventricular extension, and exhibit precipitous postnatal decline into adulthood.

Figure 1. Neurogenesis in the postnatal human SVZ.

(A) In the infant human brain, a large number of neuroblasts derived from the subventricular zone (SVZ) migrate not only into the olfactory bulb (OB) through the rostral migratory stream (RMS), but also into the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) through the medial migratory stream (MMS). (B) In the adult human brain, only few migrating neuroblasts in isolation are present in the SVZ and the remnant RMS. Postnatal migration of neuroblasts occurs in the absence of olfactory ventricular extension.

One exciting novel finding from Sanai et al (2011) is the identification of a second route, the medial migratory stream (MMS; Figure 1A) of neuroblasts targeting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) in human specimens aged 4–6 months, but not 8–18 months. The MMS contains large number of migrating neuroblasts, some of which express interneuron markers calretinin and tyrosine hydroxylase. These immature interneurons were also found in a restricted subregion of the VMPFC, but largely absent in adjacent prefrontal areas. In contrast, Sanai et al. (2011) did not observe a robust MMS in postnatal mice, but only individual DCX+ cells migrating ventrally and laterally that might target analogous regions. A previous study employing transgenic mice expressing EGFP in 5-HT3aR+ neurons revealed a much more widespread migration of different GABAergic immature neurons from juvenile postnatal SVZ into numerous forebrain structures, including prefrontal cortex, although a distinct migratory stream was not evident (Inta et al., 2008).

These exciting new findings confirm the significant regenerative capacity of human brains, especially during infancy, and reveal critical properties of SVZ neurogenesis, including diverse neuronal subtypes, contribution to different brain regions and the time-course of decline. The substantial contribution of SVZ neurogenesis to prefrontal cortical circuitry raises the possibility that aberrant postnatal development of these new neurons may be involved in pathogenesis of mental disorders, such as schizophrenia. These findings may also provide insight into other neonatal brain diseases, especially those arising from pathology in periventricular structures. In addition, the lack of significant proliferation and limited number of neural stem cells and progenitors in adult human SVZ may set the limit for their contribution to brain tumors.

These fascinating findings also raise new questions. First, what are the properties and function of SVZ-derived neurons in human prefrontal cortex? More detailed study in rodents and primates is warranted, given the observation of robust migrating SVZ-derived new neurons to cortical areas in early postnatal mice (Inta et al., 2008) and available tools for detailed lineage-tracing, histological characterization, electrophysiological analysis and, potentially, genetic elimination for behavioral analysis. Second, is there a common precursor for newborn neurons targeting to the olfactory bulb and prefrontal cortex, or is early postnatal human SVZ pre-patterned with restricted potential precursors as in rodents (Merkle et al., 2007)? Third, what is the mechanism underlying the rapid decline of neurogenesis in postnatal human SVZ? As exemplified by these recent studies, it is very fruitful and rewarding to study human systems directly. With the development of better tools and a collaborative spirit, the best chapters for postnatal human neurogenesis research are yet to come.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, Holtas S, van Roon-Mom WM, Bjork-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, et al. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science. 2007;315:1243–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1136281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Cazares H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Soriano-Navarro M, Zamora-Berridi G, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Cytoarchitecture of the lateral ganglionic eminence and rostral extension of the lateral ventricle in the human fetal brain. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:1165–1180. doi: 10.1002/cne.22566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inta D, Alfonso J, von Engelhardt J, Kreuzberg MM, Meyer AH, van Hooft JA, Monyer H. Neurogenesis and widespread forebrain migration of distinct GABAergic neurons from the postnatal subventricular zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20994–20999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807059105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoth R, Singec I, Ditter M, Pantazis G, Capetian P, Meyer RP, Horvat V, Volk B, Kempermann G. Murine features of neurogenesis in the human hippocampus across the lifespan from 0 to 100 years. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Nguyen T, Ihrie RA, Mirzadeh Z, Tsai HH, Wong M, Gupta N, Berger MS, Huang E, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, Lawton MT, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Manuel-Garcia Verdugo J, et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Liu F, Liu YY, Zhao CH, You Y, Wang L, Zhang J, Wei B, Ma T, Zhang Q, et al. Identification and characterization of neuroblasts in the subventricular zone and rostral migratory stream of the adult human brain. Cell Res. 2011 doi: 10.1038/cr201183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]