Abstract

Objective

To present the profiles of spinal cord tumors that can be removed through a unilateral hemilaminectomy and to demonstrate its usefulness for benign spinal cord tumors that significantly occupy the spinal canal.

Methods

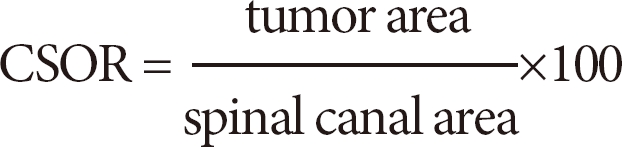

From June 2004 to October 2010, 25 spinal cord tumors were approached with unilateral hemilaminectomy. We calculated the cross-sectional occupying ratio (CSOR) of tumor to spinal canal before and after the operations.

Results

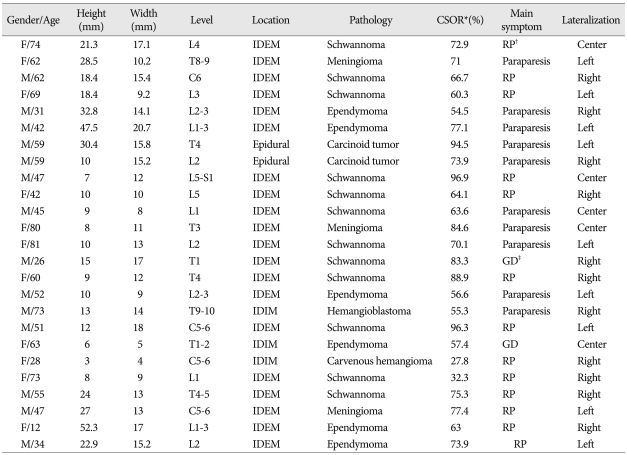

The locations of the tumors were intradural extramedullary in 20 cases, extradural in 2, and intramedullary in 3. The levels of the tumors were lumbar in 12, thoracic 9, and cervical 4. In all cases, the tumor was removed grossly and totally without damaging spinal cord or roots. The mean height and width of the lesions we195re 17.64 mm (3-47.5) and 12.62 mm (4-32.7), respectively. The mean CSOR was 69.40% (range, 27.8-96.9%). Postoperative neurological status showed improvement in all patients except one whose neurologic deficit remained unchanged. Postoperative spinal stability was preserved during the follow-up period (mean, 21.5 months) in all cases. Tumor recurrence did not develop during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

Unilateral hemilaminectomy combined with microsurgical technique provides sufficient space for the removal of diverse spinal cord tumors. The basic profiles of the spinal cord tumors which can be removed through the unilateral hemilaminectomy demonstrate its role for the surgery of the benign spinal cord tumors in various sizes.

Keywords: Laminectomy, Microsurgery, Spinal cord neoplasms, Unilateral hemilaminectomy, Spinal ligaments

INTRODUCTION

The unilateral hemilaminectomy for the surgery of cord tumors was first described in 1991 by Yasargil et al.19). Advances in microsurgical technique and modern microsurgical equipment have added its usefulness to cord tumor surgery. Sporadic results of surgery for spinal cord tumors using a unilateral hemilaminectomy have been reported by many authors2-5,7,10,11,14,17,19). Small tumors can be removed through a hemilaminectomy without difficulty. However, the majority of tumors in the spinal canal are benign and the symptoms are typically provoked by a mass effect, where the tumor already occupied most of the spinal canal when the tumor is detected using imaging techniques. It is still difficult to decide the extent of laminectomy in case of cord tumors that significantly occupy the spinal canal.

Unilateral hemilaminectomy has more benefits with regard to postoperative spinal stability comparing with a total laminectomy1,5,9). However, unilateral hemilaminectomy has not been a widely accepted surgical option for the removal of spinal cord tumors. This may be because of surgeons' concerns about incomplete removal of the tumor or inadvertent spinal cord damage with the relatively narrow surgical corridor.

In this study, we retrospectively investigated the profiles of spinal cord tumors that could be removed through a unilateral hemilaminectomy. We would like to illuminate the role of unilateral hemilaminectomy for benign spinal cord tumors that significantly occupy the spinal canal. Some technical tips are also discussed for overcoming the narrow surgical corridor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed data obtained about tumors in the spinal canal that were removed through a unilateral hemilaminectomy between June 2004 and October 2010. Metastatic lesions that need extensive bone removal, purely cystic lesions, or lesions that required spinal cord biopsies were excluded. The spinal level, location in the spinal canal, and size of the removed tumor were evaluated. Pathological reports of each extracted tumor were also evaluated.

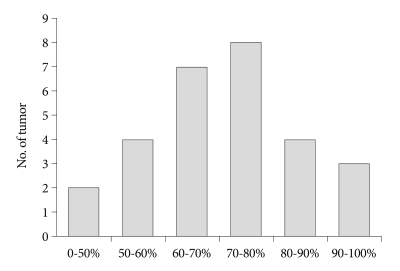

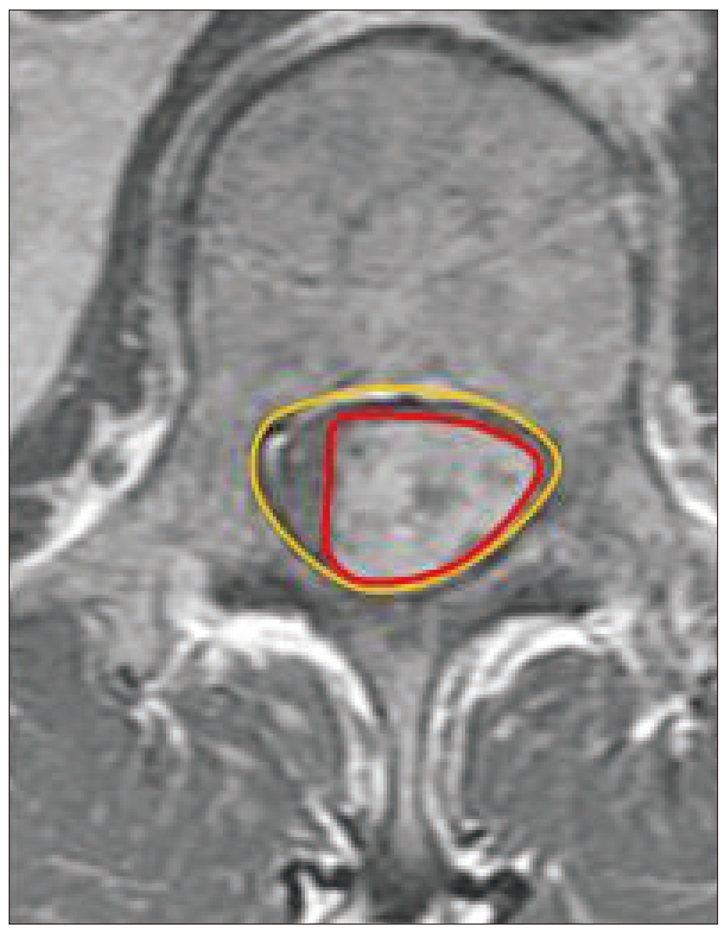

We calculated the cross-sectional occupying ratio (CSOR) of the tumor to the spinal canal at the thickest level with an area measuring tool of the picture archiving and communication system (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cross-sectional occupying ratio on MRI : Outer round circle indicates spinal canal area. Inner irregular circle indicates cord tumor area.

The descriptive tables representing the numbers of tumor and were statistically verified by Fisher's extract test.

Operative methods and technical tips

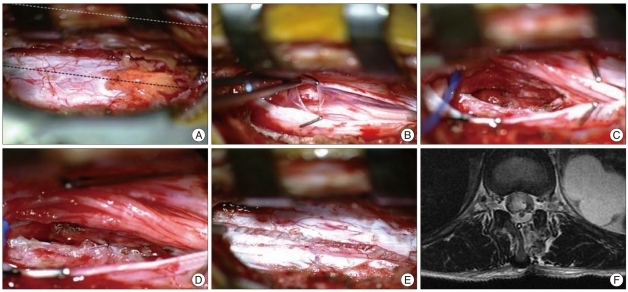

Patients were placed in the prone position under general anesthesia and the surgeries were performed by one spinal neurosurgeon. Unilateral subperiosteal muscle dissection was performed and the lamina was exposed in a way similar to the techniques used for unilateral hemilaminectomy and discectomy. The dural sac was exposed by drilling the lamina, including the base of the spinous process, while preserving the facet joint. To overcome the narrow field of the unilateral hemilaminectomy, we employed several operative technical tips. Combining undercutting of the base of the spinous processes and oblique tilting of the operating table to the controlateral side provided an adequate view for the extradural and intradural procedures. Internal debulking of a solid tumor or piecemeal resection helps the dissection. After debulking of the tumor to at least some degree, delivery of the remaining tumor mass out from the spinal canal accelerated the following procedures. If the tumor has a cystic component, draining cystic fluid by puncture or aspiration can also make the dissection easier. Another technical tip is the lateral dural tacking method, which is tacking the ipsilateral dural margin and suture with the base of the muscle or fascia near the facet joint, instead of lifting it up or suspending it (Fig. 2). Applying cottonoid to the upper and lower pole helps to prevent the excessive spread of blood clots into the spinal canal. An intraoperative ultrasonic aspirator provided no benefit because of its narrow window but it is not usually necessary for a benign spinal cord tumor. Finally, the dural sac can be approximated with noninterrupted sutures using 7.0 or 8.0 Prolene. Mobilizing the dural sac to the ipsilateral side by pulling the sutured string near the knot with a nerve hook helps with the manipulation of each stitch.

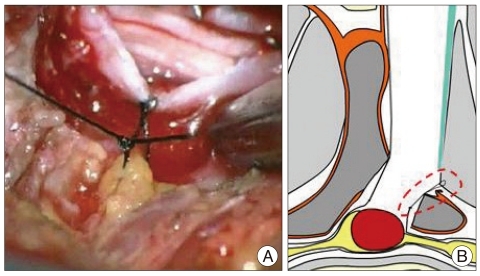

Fig. 2.

Lateral dural tacking method : take up the opened ipsilateral dural margin with the base of the muscle or fascia near the facet joint. The operative scene (A) and schematic drawing (B) are shown.

RESULTS

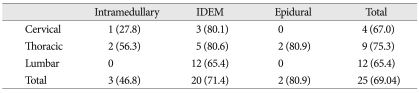

Twenty-five tumorous lesions of 24 enrolled patients were removed through unilateral hemilaminectomy (one patient had two separate lesions). The characteristics of the lesions and its basic profiles are summarized (Table 1). The patients consisted of 14 males and 10 females with a mean age of 51 years (12-81). The location of tumors were 2 extradural, 20 intradural extramedullary, and 3 intramedullary locations (Table 2). The relationship between tumor location and mean CSOR was depicted. The levels of the tumors were cervical in 4, thoracic 9, and lumbar 12 (Table 1, 2, 3).

Table 1.

The summarized characteristics of the lesions and its basic profiles

*Cross sectional occupying ratio, †Radiating pain, ‡Gait disturbance. CSOR : cross-sectional occupying ratio, IDEM : intradural extramedullary

Table 2.

Numbers of tumor and mean CSOR (in parenthesis) according to tumor location and spinal level

IDEM : intradural extramedullary, CSOR : cross-sectional occupying ratio

Table 3.

Numbers of tumor and mean CSOR (in parenthesis) according to pathologic report and spinal level

*Carcinoid tumor, hemangioblastoma, carvenous hemangioma. CSOR : cross-sectional occupying ratio

All tumors were successfully removed without damaging the cord or the major osteoligamentous complexes in the midline of the spine. The mean height and width of the lesions were 17.04 mm (3-47.5) and 12.62 mm (4-32.7), respectively. The mean occupying ratio was 69.04% (Fig. 3). The levels of laminectomies were varying from one to 2.5. The postoperative neurological status was improved in all patients except one, whose neurological deficit remained unchanged.

Fig. 3.

The number of tumors according to CSOR. CSOR : cross-sectional occupying ratio

The pathological reports were schwannoma in 12, ependymomma in 6, meningioma 3, carcinoid tumor 2, hemangioblastoma 1 and carvenous hemangioma 1.

The relationship between pathologic report and mean CSOR was depicted in Table 3.

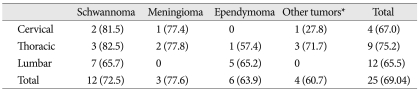

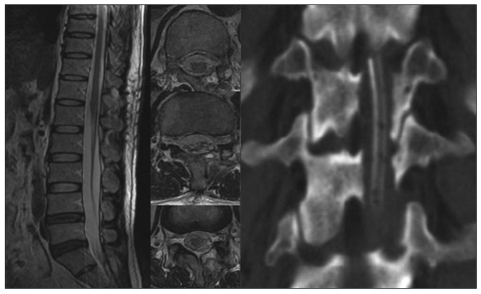

Postoperative spinal stability remained intact during the follow-up period (mean, 21.5 months) in all three cases. Complications, such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage, postoperative instability, and aggravation of neurological status, did not occur. Temporary dysesthesia developed postoperatively in one patient. The patient was observed without any surgical intervention, and the symptom was completely resolved during the hospital stay. All tumors were grossly removed and tumor recurrence did not develop during the follow-up period. Intraoperative conversion to total laminectomy during the operation was not necessary any case. Three cases of the intramedullary tumor were approached with similar technique. To describe the accessibility for the controlateral aspect of spinal canal, serial step of the intraoperative scene for an intramedullary tumor was captured (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Serial intraoperative scene for the surgery of the intramedullary cord tumor. A : Surgical window showing sufficient view for the controlateral aspect of spinal canal. The black and white dotted line indicates the midline of spinal dural sac and osteoligamentous structure at the midline, respectively. B : Tacking up the arachnoid to the dura. C : Tumor cavity in the cord. D and E : Suturing the pia and dura. F : postoperative MRI axial finding.

Illustrative case

A 42-year-old man presented with paraparesis and voiding difficulty. The MRI revealed a 47 mm high by 19 mm wide lesion at the T12-L2 level (Fig. 5). The CSOR was 77.5%. The lesion was removed through a two-level unilateral hemilaminectomy. Postoperative MRI findings showed complete removal of the tumor with no cord damage (Fig. 6). The pathological diagnosis was myxopapillary ependymoma. Full neurological recovery was attained postoperatively.

Fig. 5.

Preoperative MRI T2 image : heterogeneous mass displacing the conus medullaris with mixed enhancement pattern on T12, L1, and L2.

Fig. 6.

Postoperative 15 days later MRI and immediate postoperative coronal CT : Removal of tumor can be indentified through the unilateral hemilaminectomy at T12 and L1.

DISCUSSION

The conventional total laminectomy has been employed for surgical removal of spinal cord tumors. It offers some convenience to spinal surgeons, such as familiar exposure and wide views of the surgical fields. However, total laminectomy also has disadvantages that can complicate postoperative outcomes. It produces overt spinal instability, leading to spinal deformity, epidural fibrosis, the absence of osseous protection for the spinal cord and postoperative axial pain. Well-recognized postlaminectomy kyphosis, especially in children, is commonly associated with instability and results in an anterior compression of the spinal cord that can cause progressive myelopathy1,2,4,10,12).

To reduce postlaminectomy complications, various operative techniques were developed. Some authors presented advantages of laminoplasty in maintaining postoperative stability and preventing epidural scar formation3,11,16). However, the advantage of laminoplasty in maintaining postoperative stability is not considered because laminoplasty can still disrupt the posterior ligamentous structures on the dorsal spine. The integrity of ligament flavum, supraspinous, and interspinous ligaments is known to be crucial for the dynamic stability of the spine. Takashi et al. stated that expansive laminoplasty may deform the spinal curvature postoperatively, so surgeons must pay careful attention to the possibility of postoperative spinal deformity2). Unilateral hemilaminectomy avoids damage to the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, and the paravertebral muscle of the opposite side. For this reason, unilateral hemilaminectomy results in less injury to the dynamic dorsal structures of the vertebral column compared with total laminectomy or even laminoplasy11,18). Unilateral hemilaminectomy is thought to be able to surpass laminoplasty in the aspect of the dynamic stability of the spine.

The advantages of unilateral hemilaminectomy include reduced postoperative pain, earlier mobilization, and shorter hospital stays1,8,9,13,15).

One possible disadvantage of unilateral hemilaminectomy is a narrow surgical corridor formed by the spinous process and ipsilateral facet joint. This is the main reason that this procedure is still not widely accepted, even though the introduction of this procedure is not recent and its benefits are evident5-7,11,12). To overcome this, we have adopted several operation techniques. The novel lateral dural tacking method, which mobilizes the dural sac slightly lateral, makes the visualization better and provides more working space. This surgical tip may also help to prevent postoperative epidural hematomas on the ventral aspect of the dural sac, which can lead to a rare but potentially disastrous complication.

Our experience indicates that unilateral hemilaminectomy is useful for the removal of various kinds of tumors in the spinal canal. All but one patient showed marked neurological improvement. The one patient who showed slight worsening of neurological symptom was an intramedullary ependymoma at the upper thoracic level and extensive syringomyelia at the below of the tumor level. The immediate postoperative symptoms of paraparesis and hyperesthesia were worsened, but gradually recovered to the preoperative state. The procedures were uneventful and the surgical view was sufficient, so we think the worsening of the patient's symptoms was not directly related to the surgical approach, but rather may have been based on the tumor pathology itself. This idea is also consistent with other reports5).

Most of the patients presented radiating pain or myelopathic symptoms. Analyses of data from the 25 cases revealed that the remaining spinal canal area was decreased to 20-30% of the normal spinal canal. The mean CSOR was 69.04%. An impressive case of schwannoma showed the maximal CSOR to be 96.9% at the L5/S1 level. Six cases (25%) showed maximal CSOR of more than 80%.

In the early period of this series, we planned to convert to conventional total laminectomy if the removal of the tumor was not feasible through the unilateral hemilaminectomy. However, there was ultimately no case of conversion to a total laminectomy. Since we adopted the unilateral hemilaminectomy for the removal of spinal cord tumors, all consecutive cases of spinal cord tumor have been removed with a unilateral hemilaminectomy. Although some authors favored unilateral hemilaminectomy for intradural extramedullary tumor, they used conventional total laminectomy for intramedullary tumors5,9,12). However, in our series, three intramedullary tumors were grossly removed with unilateral hemilaminectomy. The surgical approach cannot be difference between intradural extramedullary and intramedullar tumor because the controlateral space of spinal canal can be secured in both tumor entities. The distribution of the spinal cord tumors was variable. Because the thoracic spine has the least canal diameter, removal of the tumors in the thoracic region with unilateral hemilaminectomy was considered more difficult than in the cervical or lumbar region. The thoracic spine has a shallower surgical corridor from the skin surface to the spinal canal compared with cervical and lumbar regions. It may be advantageous to tilt the operating microscope or operating table to view the controlateral side of the spinal canal. We did not encounter any difficulties during the surgery of the nine thoracic cord tumors.

CONCLUSION

Unilateral hemilaminectomy combined with several microsurgical technique provides sufficient room for the removal of spinal cord tumors. We recommend unilateral hemilaminectomy as a suitable surgical option for the removal of diverse tumors in the spinal canal. The profiles of spinal cord tumors which can be removed through the unilateral hemilaminectomy demonstrate its role for the surgery of the benign spinal cord tumors which is significantly occupying the spinal canal.

References

- 1.Agrawal A, Cincu R, Wani B. [Modified posterior unilateral laminectomy for a complex dumbbell schwannoma of the thoracolumbar junction] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009;43:535–539. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2009.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asazuma T, Nakamura M, Matsumoto M, Chibo K, Toyama Y. Postoperative changes of spinal curvature and range of motion in adult patients with cervical spinal cord tumors : analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:178–182. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balak N. Unilateral partial hemilaminectomy in the removal of a large spinal ependymoma. Spine J. 2008;8:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertalanffy H, Mitani S, Otani M, Ichikizaki K, Toya S. Usefulness of hemilaminectomy for microsurgical management of intraspinal lesions. Keio J Med. 1992;41:76–79. doi: 10.2302/kjm.41.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiou SM, Eggert HR, Laborde G, Seeger W. Microsurgical unilateral approaches for spinal tumour surgery : eight years' experience in 256 primary operated patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1989;100:127–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01403599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi WR, Shin WH, Byun BJ. Clinical Analysis of Spinal Cord Tumor. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2001;30:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue A, Ikata T, Katoh S. Spinal deformity following surgery for spinal cord tumors and tumorous lesions : analysis based on an assessment of the spinal functional curve. Spinal Cord. 1996;34:536–542. doi: 10.1038/sc.1996.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch-Wiewrodt D, Wagner W, Perneczky A. Unilateral multilevel interlaminar fenestration instead of laminectomy or hemilaminectomy : an alternative surgical approach to intraspinal space-occupying lesions. Technical note. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:485–492. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannion RJ, Nowitzke AM, Efendy J, Wood MJ. Safety and efficacy of intradural extramedullary spinal tumor removal using a minimally invasive approach. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:208–216. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207b3c7. discussion 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura H, Komagata M, Nishiyama M, Taguchi M, Kawasaki N. Resection of a dumbbell-shaped thoracic neurinoma by hemilaminectomy : a case report. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;13:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oktem IS, Akdemir H, Kurtsoy A, Koç RK, Menkü A, Tucer B. Hemilaminectomy for the removal of the spinal lesions. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:92–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa H, Kokubun S, Aizawa T, Hoshikawa T, Kawahara C. Spinal dumbbell tumors : an analysis of a series of 118 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:587–593. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/12/587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pompili A, Caroli F, Cattani F, Crecco M, Giovannetti M, Raus L, et al. Unilateral limited laminectomy as the approach of choice for the removal of thoracolumbar neurofibromas. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1698–1702. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000132311.89236.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sario-glu AC, Hanci M, Bozkuş H, Kaynar MY, Kafadar A. Unilateral hemilaminectomy for the removal of the spinal space-occupying lesions. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1997;40:74–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sim JE, Noh SJ, Song YJ, Kim HD. Removal of intradural-extramedullary spinal cord tumors with unilateral limited laminectomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;43:232–236. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.43.5.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song YK, Jahng TA. The Usefulness of Laminoplasty in Cervical Spinal Cord Tumor Surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004;35:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takamura Y, Uede T, Igarashi K, Tatewaki K, Morimoto S. Thoracic dumbbell-shaped neurinoma treated by unilateral hemilaminectomy with partial costotransversectomy--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1997;37:354–357. doi: 10.2176/nmc.37.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tredway TL, Santiago P, Hrubes MR, Song JK, Christie SD, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive resection of intradural-extramedullary spinal neoplasms. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:ONS52–ONS58. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000192661.08192.1c. discussion ONS52-ONS58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasargil MG, Tranmer BI, Adamson TE, Roth P. Unilateral partial hemi-laminectomy for the removal of extra- and intramedullary tumours and AVMs. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1991;18:113–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6697-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]