Abstract

Purpose

To determine the incidence of Herpes zoster in patients with one of 17 specific underlying diseases compared with that in patients with other underlying diseases.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective hospital-based cohort study using data from patients’ electronic medical records for the period 2001–2007 of the Kitano Hospital Research Database. These analyses included 55,492 patients with one of 17 underlying diseases, which were those reported as related to the contraction of Herpes zoster. Of these, 769 patients contracted Herpes zoster. The main outcome measure was the clinical diagnosis of Herpes zoster.

Results

The adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for Herpes zoster in patients with the 17 diseases were compared with other patients, with the following results: brain tumor [3.84 (2.51–5.88)], lung cancer [2.28 (1.61–3.22)], breast cancer [2.41 (1.52–3.82)], esophageal cancer [4.19 (2.16–8.11)], gastric cancer [1.95 (1.39–2.72)], colorectal cancer [1.85 (1.33–2.56)], gynecologic cancer [3.45 (2.08–5.70)], malignant lymphoma [8.23 (6.53–10.38)], systemic lupus erythematosus [3.90 (2.66–5.70)], rheumatoid arthritis [2.00 (1.60–2.50)], diabetes mellitus [2.44 (2.10–2.85)], hypertension [2.04 (1.75–2.38)], renal failure [2.14 (1.65–2.79)], and disk hernia [2.18 (1.52–3.13)].

Conclusions

Patients with diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and malignancies have a 1.8–8.4-fold higher risk of a Herpes zoster event than patients with other diseases. Future studies should investigate alteration of the immune system in the underlying diseases and approaches for Herpes zoster prevention.

Keywords: Herpes zoster, Underlying disease, Incidence, Risk

Introduction

Herpes zoster (HZ), which occurs at all ages, is a clinical manifestation of the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Reactivation of latent infection results from declining specific cell-mediated immunity [1], which subsequently engenders HZ [1–3]. The estimated lifetime risk of developing HZ in those exposed to varicella is 10–30%. The incidence of HZ per 1,000 person-years ranges between 1 and 5 [4, 5]. Associations between the incidence of HZ and malignancies such as lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, cancer, autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [6–8], rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [9–11], psychological disease [12], and major depression [13] have been recognized. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was recently reported as a risk factor for HZ [14]. Disseminated zoster in elderly patients with hypertension and congestive heart failure was also reported recently [15]. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether the risk of developing HZ increases in patients with common underlying diseases that might alter immune functions. Through this single hospital-based study at Kitano Hospital in Osaka, Japan, we investigated the respective contributions of various diseases to the incidence of developing HZ.

Materials and methods

Study design

A hospital-based retrospective cohort study was conducted based on the database of the Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute, Kitano Hospital.

Data sources

Data were collected from adult patients with histories of 1 of 17 specific underlying diseases, who had visited the emergency departments, outpatient clinics, and inpatient departments. This hospital, located in the center of the Kita ward in Osaka, plays a central role in community health care. In the Japanese system, patients are free to consult any provider—primary care or specialist—at any time [16]. The patients usually visit the same hospital even when they present only mild clinical symptoms and signs. The study period was September 1, 2001 to December 31, 2007.

Inpatient and outpatient records were reviewed. They included data of patient age, sex, and underlying comorbidity, date of the first outpatient visit, admission and discharge, vital status at discharge, and outpatient and inpatient diagnoses (ICD-10-CM codes). Medical records of all patients were also reviewed for patient data and clinical characteristics from the day of diagnosis of the selected diseases to the day of occurrence of HZ, the last day of follow-up, death, or end of data abstraction (December 31, 2007). The institutional ethics committee provided approval for the retrospective review of the patient data.

Cohort selection

The cohort included patients who had ICD-10-CM code diagnoses of the underlying diseases of interest. To assist in estimating associations between the underlying diseases and HZ, we selected diseases that had been reported previously to be related with HZ (i.e., eight malignant diseases of brain tumor, lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, and malignant lymphoma; three autoimmune diseases of SLE, RA, Sjögren’s syndrome; and one psychiatric disease of depression) or might plausibly be associated with VZV infection or with impaired immunological responses to VZV (one metabolic disease of DM, one cardiovascular disease of hypertension, and one renal disorder of renal failure). Patients with diseases that had no plausible association with HZ (e.g., one osteoskeletal disease; disk hernia, one ocular disease; cataract) were selected as controls.

This study evaluated 17 diseases. Patients with one of those 17 diseases were enrolled at the first diagnosis recorded in the patient file. Diseases of enrolled patients were as follows (ICD-10-CM codes): cancer—brain tumor (C719, D320, 330–332, 420, 430–432), lung cancer (C330, 340–343, 348–349), breast cancer (C501–505, 509, 792, 795), esophageal cancer (C150–155, 159), gastric cancer (C161–164, 169), colorectal cancer (C180–190, 200), gynecologic cancer (C538–539, 541, 542, 549, 550, 560), and malignant lymphoma (C810–813, 819–822, 829–844, 851, 857, 859); autoimmune diseases—SLE (M320–321, 329), RA (M0530, 0590, 0600, 0690–0697), and Sjögren’s syndrome (M350); metabolic disease—DM (E100–107, 109–117, 119, 120, 130–137, 139–146, 149); cardiovascular disease—hypertension (I100, 110, 119,120, 129, 39, 141, 150-152, 159); renal disorder—renal failure (N179, 180, 189,190, 990); osteoskeletal disease—disk hernia (M502, 512); ocular disease—cataract (H250–252, 258–264, 268–269); and mood disorder—depression (F030, 063, 107, 191, 197, 204, 251, 313–315, 318–323, 328–334, 339, 341, 348, 349, 381, 412, 432, 530, 920).

Outcome

The study endpoint was the first occurrence of HZ. Incident cases were defined as the first incidence of HZ based on the record of a doctor’s diagnosis and identified from inpatient and outpatient encounters that included ICD-10-CM code B020–023, 027–029 (HZ). For all analyses, incident cases of HZ occurring after the patient’s cohort entry date were ascertained using the first HZ diagnosis recorded in the patient file in the Kitano Hospital database. Patients who had HZ at any time prior to the diagnosis of the 17 underlying diseases and those with recurrent HZ were excluded. The incidence of HZ was calculated as the number of events per 1,000 patient-years.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier estimation, defined as the base hazard function for the acquisition of HZ along with age, was used to determine the cumulative HZ-free survival rate incidence during the first 6 years of underlying disease. The Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare the rates of HZ among patients with each of the 17 diseases and to determine the risks of developing HZ. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated after adjustment for age and other comorbidities. Statistical significance was inferred for p value <0.05. All statistical tests were two-sided and were performed using a statistical software package (Stata ver. 10 for Windows; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Study population and patient characteristics

The full cohort included 55,492 patients who had one or more of the 17 diseases (with or without HZ) at Kitano Hospital: 25,998 (47%) of the patients were male and 29,494 (53%) were female. The mean age at diagnosis was 60.1 years (range 20–103 years). The characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population: of 55,492 patients with one of 17 specific diseases, 769 patients subsequently developed Herpes zoster

| Disease | All subjects | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HZ (+) | HZ (−) | ||

| All subjects | 769 | 54,723 | 55,492 |

| Mean age (SD) | 63.95 (13.75) | 60.03 (16.55) | 60.09 (16.52) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 373 | 25,625 | 25,998 |

| Mean age (SD) | 64.13 (12.59) | 59.54 (15.93) | 59.61 (15.90) |

| Female | 396 | 29,098 | 29,494 |

| Mean age (SD) | 63.79 (14.77) | 60.47 (17.06) | 60.51 (17.03) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 20–29 | 22 | 3,433 | 3,455 |

| 30–39 | 30 | 4,288 | 4,318 |

| 40–49 | 51 | 4,979 | 5,030 |

| 50–59 | 149 | 10,624 | 10,773 |

| 60–69 | 231 | 14,570 | 14,801 |

| 70–79 | 222 | 12,638 | 12,860 |

| 80–89 | 60 | 3,823 | 3,883 |

| 90–99 | 4 | 366 | 370 |

| ≥100 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

HZ outcomes

As noted, 769 (1.4%) of the 55,492 patients subsequently developed HZ during the 6-year study period, of which 373 (49%) were male and 396 (51%) were female. The annualized incidence rate of HZ was 2.2 episodes per 1,000 patient-years. The age-related changes of the incidence of HZ are shown in Table 1. Precise descriptive characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 55,492 patients with 17 underlying diseases at Kitano Hospital

| Disease | Total | HZ (−) | HZ (+) | Age of total subjects | Age of HZ patients | Gender (number of subjects) | Gender (number of HZ patients) | Duration to HZ* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Male | Female | Male | Female | Mean | SD | ||||

| Brain tumor | 1,393 | 1,371 | 22 | 54.15 | 18.21 | 65.85 | 9.87 | 624 | 769 | 7 | 15 | 2.09 | 2.01 |

| Lung cancer | 1,410 | 1,375 | 35 | 67.71 | 11.95 | 68.00 | 10.08 | 906 | 504 | 26 | 9 | 1.08 | 1.15 |

| Breast cancer | 1,469 | 1,450 | 19 | 57.90 | 13.26 | 61.12 | 13.45 | 8 | 1,461 | 0 | 19 | 1.40 | 1.23 |

| Esophageal cancer | 307 | 298 | 9 | 65.85 | 9.37 | 64.93 | 8.80 | 240 | 67 | 7 | 2 | 1.29 | 1.51 |

| Gastric cancer | 1,777 | 1,740 | 37 | 66.35 | 11.70 | 66.32 | 9.56 | 1,186 | 591 | 24 | 13 | 1.90 | 1.66 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1,924 | 1,885 | 39 | 66.14 | 12.22 | 71.02 | 10.12 | 1,110 | 814 | 24 | 15 | 1.78 | 1.73 |

| Gynecologic cancer | 1,124 | 1,108 | 16 | 52.76 | 15.33 | 55.29 | 10.13 | 1 | 1,123 | 0 | 16 | 1.28 | 1.37 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 1,917 | 1,824 | 93 | 48.31 | 23.26 | 56.88 | 16.10 | 912 | 1,005 | 44 | 49 | 1.09 | 1.14 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1,077 | 1,039 | 38 | 48.23 | 19.29 | 51.18 | 20.88 | 252 | 825 | 10 | 28 | 1.82 | 1.76 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6,714 | 6,604 | 110 | 55.60 | 17.36 | 62.90 | 14.49 | 2,825 | 3,889 | 36 | 74 | 1.71 | 1.57 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 1,147 | 1,131 | 16 | 55.83 | 16.06 | 57.35 | 18.52 | 176 | 971 | 3 | 13 | 1.44 | 1.68 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15,790 | 15,517 | 273 | 63.06 | 13.23 | 64.79 | 12.53 | 9,248 | 6,542 | 152 | 121 | 1.69 | 1.57 |

| Hypertension | 15,975 | 15,693 | 282 | 64.88 | 13.59 | 67.04 | 12.03 | 8,546 | 7,429 | 147 | 135 | 1.70 | 1.60 |

| Renal failure | 2,577 | 2,504 | 73 | 65.98 | 14.94 | 66.88 | 12.10 | 1,543 | 1,034 | 43 | 30 | 1.52 | 1.57 |

| Disc hernia | 2,804 | 2,773 | 31 | 50.36 | 17.13 | 63.81 | 13.57 | 1,591 | 1,213 | 14 | 17 | 2.09 | 1.72 |

| Cataract | 18,247 | 18,049 | 198 | 68.45 | 10.84 | 69.03 | 8.48 | 7,908 | 10,339 | 94 | 104 | 1.65 | 1.58 |

| Depression | 6,803 | 6,761 | 42 | 52.00 | 18.86 | 64.91 | 12.89 | 2,666 | 4,137 | 15 | 27 | 1.34 | 1.44 |

* Time in years from underlying disease to HZ: period from the onset of the underlying disease to the time of the first development of HZ

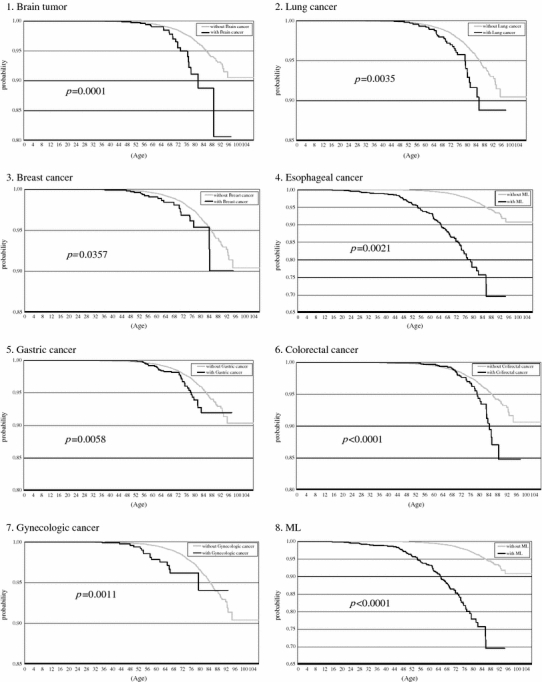

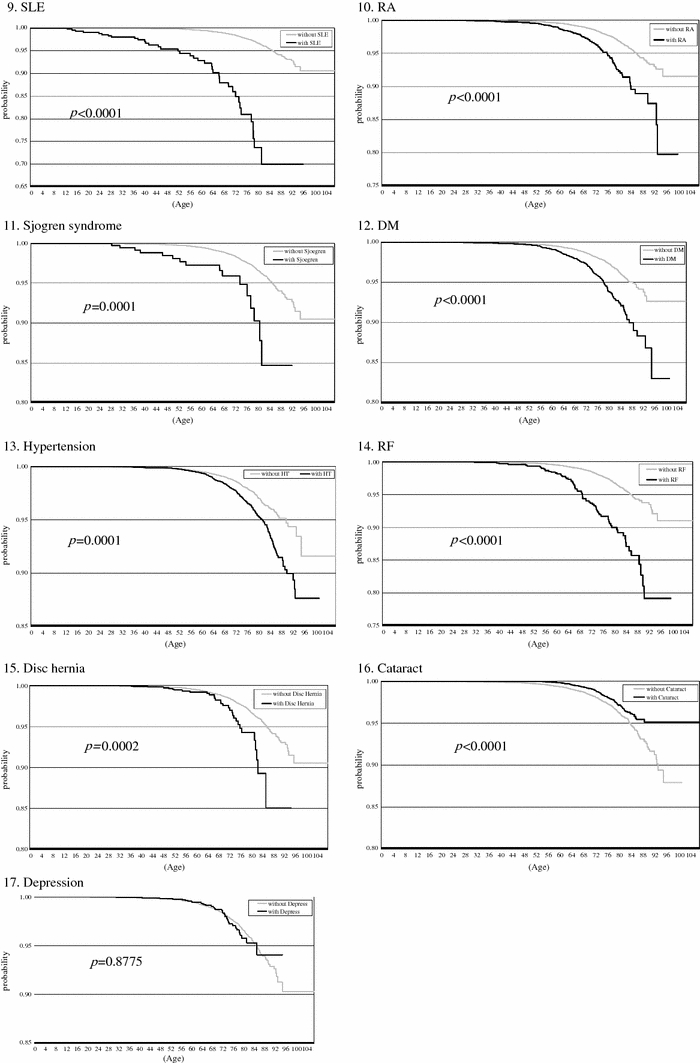

For univariate analysis, the Kaplan–Meier hazard function for the acquisition of HZ in the patients with underlying diseases is portrayed in Fig. 1. During the 6.3 years of observation, a log-rank test showed that patients with one of the following 16 diseases had significantly lower survival rates than that of the cohort without these diseases: brain tumor, lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, malignant lymphoma, SLE, RA, Sjögren’s syndrome, DM, hypertension, renal failure, disk hernia, and cataract. Patients with depression did not have significantly different survival rates from those of disease-free controls.

Fig. 1.

Patients with depression showed no significantly lower event-free survival rate than the cohort without the disease (17). Patients with one of the other 16 underlying diseases showed significantly lower event-free survival rate than the cohort without the index disease (1–16). Kaplan–Meier plots of Herpes zoster event-free survival over 6 years of follow-up after the time of the first diagnosis of underlying disease in 2001–2007 at the Kitano Hospital Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute. The x-axis shows age. The y-axis shows probability. p-values are derived using the log-rank test

Potential risk factors for HZ

The associations between the underlying diseases and subsequent HZ events were determined using Cox proportional hazards models. For univariate analysis, 15 diseases were independently associated with increased risk for subsequent HZ events (Table 3). For multivariate analysis, the Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for age showed that the following 14 diseases significantly increased the risk of developing HZ: brain tumor, lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, malignant lymphoma, SLE, RA, DM, hypertension, renal failure, and disk hernia. The remaining three diseases—Sjögren’s syndrome, cataract, and depression—were not associated with the risk of HZ (Table 3). Female gender had a significant inverse association with HZ in the univariate analysis, but it was not associated with subsequent HZ events in the multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Risk of Herpes zoster in the comparison cohort, 2001–2007 (n = 55,492)

| Disease or status | 1,000 person-years | Disease | Comparison patients | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZ (+) | HZ (−) | HZ (+) | HZ (−) | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | ||

| Brain tumor | 17.3 | 22 | 1,371 | 747 | 53,352 | 2.31 (1.51–3.52) | 0.000 | 3.69 (2.41–5.66) | 0.000 |

| Lung cancer | 51.9 | 35 | 1,375 | 734 | 53,348 | 1.88 (1.34–2.63) | 0.000 | 2.17 (1.53–3.08) | 0.000 |

| Breast cancer | 17.3 | 19 | 1,450 | 750 | 53,273 | 1.62 (1.03–2.56) | 0.038 | 2.34 (1.48–3.72) | 0.000 |

| Esophageal cancer | 74.1 | 9 | 298 | 760 | 54,425 | 2.70 (1.40–5.20) | 0.003 | 4.05 (2.09–7.84) | 0.000 |

| Gastric cancer | 26.9 | 37 | 1,740 | 732 | 52,983 | 1.59 (1.14–2.21) | 0.006 | 1.92 (1.37–2.67) | 0.000 |

| Colorectal cancer | 29.6 | 39 | 1,885 | 730 | 52,838 | 1.61 (1.17–2.22) | 0.004 | 1.82 (1.31–2.52) | 0.000 |

| Gynecologic cancer | 28.3 | 16 | 1,108 | 753 | 53,615 | 2.24 (1.36–3.67) | 0.001 | 3.34 (2.02–5.52) | 0.000 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 95.2 | 93 | 1,824 | 676 | 52,899 | 9.34 (7.52–11.60) | 0.000 | 8.39 (6.67–10.55) | 0.000 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 53.7 | 38 | 1,039 | 731 | 53,684 | 10.45 (7.54–14.48) | 0.000 | 4.11 (2.80–6.02) | 0.000 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 30.0 | 110 | 6,604 | 659 | 48,119 | 2.38 (1.94–2.91) | 0.000 | 2.03 (1.63–2.53) | 0.000 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 44.7 | 16 | 1,131 | 753 | 53,592 | 3.45 (2.10–5.66) | 0.000 | 1.30 (0.75–2.25) | 0.350 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24.9 | 273 | 15,517 | 496 | 39,206 | 2.14 (1.84–2.48) | 0.000 | 2.38 (2.04–2.78) | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 27.4 | 282 | 15,693 | 487 | 39,030 | 1.64 (1.41–1.90) | 0.000 | 1.93 (1.66–2.26) | 0.000 |

| Renal failure | 56.3 | 73 | 2,504 | 696 | 52,219 | 3.30 (2.59–4.20) | 0.000 | 2.21 (1.70–2.87) | 0.000 |

| Disc hernia | 24.4 | 31 | 2,773 | 738 | 51,950 | 1.94 (1.35–2.78) | 0.000 | 2.27 (1.58–3.26) | 0.000 |

| Cataract | 23.0 | 198 | 18,049 | 571 | 36,674 | 0.64 (0.54–0.75) | <0.0001 | 1.31 (0.91–1.27) | 0.399 |

| Depression | 27.4 | 42 | 6,761 | 727 | 47,962 | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.875 | 1.31 (0.95–1.80) | 0.102 |

| Female | 29,494 | 396 | 29,098 | 373 | 25,625 | 0.81 (0.71–0.94) | 0.004 | 0.90 (0.78–1.05) | 0.184 |

Significant associations were found between HZ and patients with one of 14 underlying diseases––brain tumor, lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, malignant lymphoma, SLE, RA, DM, hypertension, renal failure, and disk hernia––compared to patients with none of these diseases in this cohort. Three underlying diseases (Sjögren’s syndrome, cataract, depression) and female subjects showed no significantly higher risk of HZ

Discussion

The results showed that patients who had one of the 14 underlying diseases, i.e., brain tumor, lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, gynecologic cancer, malignant lymphoma, SLE, RA, DM, hypertension, renal failure, and disk hernia, displayed a 1.8–8.4-fold increased risk of HZ events compared to patients with none of these diseases in this cohort. No significantly higher risk of HZ was found for female patients than for male patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, patients with underlying diseases were not compared with healthy individuals. A prospective cohort study to compare patients with these underlying diseases to healthy controls would require an expensive large-scale research project, necessitating several years and a larger patient cohort. The second limitation was the observational period. Patients did not necessarily visit the same hospital after the development of HZ. We examined patients who had contracted HZ and visited the outpatient department as outpatients. Patients who had been treated in a hospital for other diseases would usually return to the outpatient department of the same hospital in the Japanese health service system. This restriction might improve the accuracy of the diagnosis and follow-up data.

It is known that VZV can be reactivated after many years and that it can induce HZ [17, 18]. People with suppressed cell-mediated immunity caused by immunosuppressive disorders or therapies are well described as having a higher risk of developing zoster. In fact, advanced age [17, 18], trauma [18], stress [18], and immune suppression are important risk factors of reactivation. Patients with medical conditions indicating compromised immunity have increased risk of developing HZ. Prior studies have identified immunosuppressive therapy (including corticosteroids), organ transplantation, malignancy [19–22], HIV disease [22–25], autoimmune disease, SLE [8, 21], and RA [9, 10, 19, 21] as HZ risk factors. Previous studies have yielded controversial results: some studies have shown DM to be a risk factor for HZ [14, 26], whereas others have not [27]. Adults with major depression have lower VZV-specific cellular immunity than controls, but they were not examined for the consequent risk of HZ [13]. A slight but insignificant association was found between HZ and depression.

Certain comorbidities were also independent risk factors for HZ in patients treated with immunosuppressive agents. Lupus nephritis was a risk factor for HZ in patients with SLE [21]. Renal dysfunction was a risk factor for HZ patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis [28]. Several medical conditions (malignancy, chronic lung disease, renal failure, and liver disease) were independent risk factors for HZ in patients with RA [11]. The results show that patients with one of 14 underlying diseases, including malignancy, autoimmune diseases, metabolic disease, hypertension, renal failure, and disk hernia, had a higher risk for HZ than patients with any other diagnosis. The results of this study showed that patients with underlying diseases have a higher risk of developing HZ, which might be attributable to the progressive decline in the VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity that occurs in conditions that compromise immune function. We have recently reported that cell-mediated immunity to VZV in DM patients was significantly lower than in healthy individuals [29]. Other comorbidities might affect VZV-specific immunity. Major depression is associated with a marked decline in VZV-specific cellular immunity in patients older than 60 years [13]. A recent population-based study demonstrated that affective psychoses increased the risk of developing HZ by 1.34-fold in patients younger than 60 years of age [12]. Depression was not associated with subsequent HZ events in this study, probably because no investigation was conducted according to age. Disk hernia patients showed a higher risk for HZ than we expected as a control, probably because most were treated surgically.

The live attenuated vaccine to prevent HZ in adults aged ≥60 years was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was recommended by the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP). It might reduce the burden of HZ and its complications greatly, including postherpetic neuralgia, in this age group. The use of a live attenuated varicella vaccine to prevent HZ would be contraindicated in persons who have impaired cellular immunity: they might develop symptomatic, progressive infection with vaccine virus [30]. An inactivated varicella vaccine might be useful for the early reconstitution of adaptive immunity to VZV after hematopoietic cell transplantation. The results of this study suggest that patients with underlying diseases should be targeted for vaccination under the monitoring of both the safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine.

Conclusions

Our study showed that patients with certain underlying diseases have a 1.8–8.4-fold heightened risk of developing Herpes zoster (HZ) compared to other patients. Although the risk of HZ in those patients was not compared to that in healthy individuals, the results revealed a significantly heightened risk among patients with metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, and renal failure, as well as those with malignant diseases and autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant for Research Promotion of Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (H18-Shinko-Ippan-013) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Arvin AM. Cell-mediated immunity to varicella-zoster virus. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:S35–S41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.Supplement_1.S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger R, Florent G, Just M. Decrease of the lymphoproliferative response to varicella-zoster virus antigen in the aged. Infect Immun. 1981;32:24–27. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.1.24-27.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke BL, Steele RW, Beard OW, Wood JS, Cain TD, Marmer DJ. Immune responses to varicella-zoster in the aged. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:291–293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.142.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605–1609. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.15.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1341–1349. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginzler E, Diamond H, Kaplan D, Weiner M, Schlesinger M, Seleznick M. Computer analysis of factors influencing frequency of infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:37–44. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moutsopoulos HM, Gallagher JD, Decker JL, Steinberg AD. Herpes zoster in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:798–802. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahl LE. Herpes zoster infections in systemic lupus erythematosus: risk factors and outcome. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Chakravarty EF. Rates and predictors of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and non-inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1370–1375. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smitten AL, Choi HK, Hochberg MC, Suissa S, Simon TA, Testa MA, et al. The risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the United States and the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1431–1438. doi: 10.1002/art.23112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald JR, Zeringue AL, Caplan L, Ranganathan P, Xian H, Burroughs TE, et al. Herpes zoster risk factors in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1364–1371. doi: 10.1086/598331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang YW, Chen YH, Lin HW. Risk of herpes zoster among patients with psychiatric diseases: a population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin M, Costlow C, Williams H, Artin KH, Chan CY, Stinson DL, et al. Cellular immunity to varicella-zoster virus in patients with major depression. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:S104–S108. doi: 10.1086/514272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heymann AD, Chodick G, Karpati T, Kamer L, Kremer E, Green MS, et al. Diabetes as a risk factor for herpes zoster infection: results of a population-based study in Israel. Infection. 2008;36:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capron J, Steichen O. Disseminated zoster in an elderly patient. Infection. 2009;37:179–180. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai Y. Health care reform in Japan. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Economics Department Working Papers. 2002.

- 17.Arvin A. Aging, immunity, and the varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2266–2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas SL, Hall AJ. What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster? Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:26–33. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schimpff S, Serpick A, Stoler B, Rumack B, Mellin H, Joseph JM, et al. Varicella-Zoster infection in patients with cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1972;76:241–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-2-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masci G, Magagnoli M, Gullo G, Morenghi E, Garassino I, Simonelli M, et al. Herpes infections in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncology. 2006;71:164–171. doi: 10.1159/000106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzi S, Kuller LH, Kutzer J, Pazin GJ, Sinacore J, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Herpes zoster in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1254–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opstelten W, Van Essen GA, Schellevis F, Verheij TJ, Moons KG. Gender as an independent risk factor for herpes zoster: a population-based prospective study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:692–695. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, Liu JY, O’Malley PM, Underwood R, et al. Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1153–1156. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan D, Mahe C, Malamba S, Okongo M, Mayanja B, Whitworth J. Herpes zoster and HIV-1 infection in a rural Ugandan cohort. AIDS. 2001;15:223–229. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101260-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veenstra J, Krol A, van Praag RM, Frissen PH, Schellekens PT, Lange JM, et al. Herpes zoster, immunological deterioration and disease progression in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1995;9:1153–1158. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown GR. Herpes zoster: correlation of age, sex, distribution, neuralgia, and associated disorders. South Med J. 1976;69:576–578. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197605000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ, Kurland LT. Herpes zoster and diabetes mellitus: an epidemiological investigation. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36:501–505. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wung PK, Holbrook JT, Hoffman GS, Tibbs AK, Specks U, Min YI, et al. Herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients: incidence, timing, and risk factors. Am J Med. 2005;118:1416. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okamoto S, Hata A, Sadaoka K, Yamanishi K, Mori Y. Comparison of varicella-zoster virus-specific immunity of patients with diabetes mellitus and healthy individuals. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1606–1610. doi: 10.1086/644646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]