Abstract

Thermodynamic parameters were determined for complex formation between the Grb2 SH2 domain and Ac–pTyr–Xaa–Asn derived tripeptides in which the Xaa residue is an α,α-cycloaliphatic amino acid that varies in ring size from 3- to 7-membered. Although the 6- and 7-membered ring analogs are approximately equipotent, binding affinities of those having 3- to 6-membered rings increase incrementally with ring size because increasingly more favorable binding enthalpies dominate increasingly unfavorable binding entropies, a finding consistent with an enthalpy-driven hydrophobic effect. Crystallographic analysis reveals that the only significant differences in structures of the complexes are in the number of van der Waals contacts between the domain and the methylene groups in the Xaa residues. There is a positive correlation between buried nonpolar surface area and binding free energy and enthalpy, but not with ΔCp. Displacing a water molecule from a protein-ligand interface is not necessarily reflected in a favorable change in binding entropy. These findings highlight some of the fallibilities associated with commonly held views of relationships of structure and energetics in protein-ligand interactions and have significant implications for ligand design.

A major challenge in molecular recognition in biological systems is knowing how changing structural features of a small molecule will affect its affinity for a target protein.1 Predicting even relative binding affinities in protein-ligand interactions is a daunting task because there is often no direct correlation between binding free energy, ΔG, and enthalpy, ΔH, or entropy, –TΔS.2 The ability to estimate protein binding affinities for a series of structurally related ligands thus requires that both binding enthalpies and entropies can be accurately predicted. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of literature in which experimental binding enthalpies and entropies are correlated with specific and/or incremental variations in ligand structure.3 Exacerbating the difficulty in predicting affinities is the phenomenon of enthalpy/entropy compensation that may be virtually balancing.4 Moreover, some paradigms that are commonly employed to guide optimization of protein-ligand interactions have recently been found to be provisional. For example, we discovered that ligand preorganization does not necessarily lead to enhanced protein binding entropies, even when flexible and constrained ligands bind in similar conformations.5,6 Although increasing nonpolar surface area of a ligand is generally viewed as having a favorable impact on binding entropy,7 hydrophobic effects in protein-ligand interactions can also be enthalpy driven.3,8,9

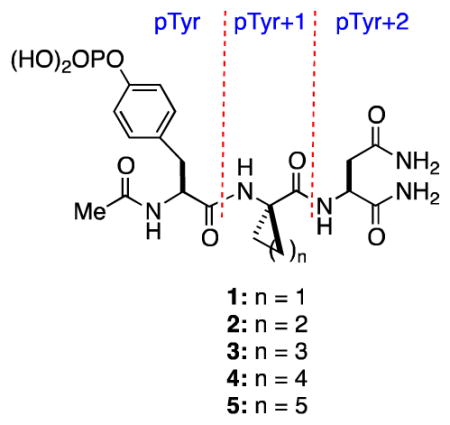

In ongoing studies directed toward correlating structure and energetics in protein-ligand interactions, we became interested in explicitly elucidating the effects of making incremental changes in the nonpolar surface area of a ligand upon protein binding enthalpies and entropies. In this context, we have found that the SH2 domain of growth receptor binding protein 2 (Grb2), a well-characterized 25 kDa cytosolic adapter protein that participates in the Ras signal transduction pathway,10 is a suitable platform for studying how small changes in the structure of Ac–pTyr–Xaa–Asn–NH2 derived peptides affect binding thermodynamics.6 We were thus attracted to studying the binding energetics of peptides 1–5, which differ only in the size of the ring of the α,α-cycloaliphatic amino acid residue at the pTyr+1 position. The inspiration for selecting these tripeptides was based upon earlier work of García-Echeverría and co-workers who found that the IC50s of 1–5 for the Grb2 SH2 domain increase with ring size, with a six-membered ring being optimal.11 Because they did not determine binding enthalpies and entropies, they were unable to identify whether the origin of the increased potency was entropic, enthalpic, or a combination of the two.]

Compounds 1–5 were thus prepared, and their binding parameters (Ka, ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS°, ΔCp) for the Grb2 SH2 domain were determined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Table 1) in accord with our previous work.6 The affinities of 1–4, which vary over a range of about 40-fold, increase incrementally with ring size with an average increase in ΔG° of 0.7 ± 0.1 kcal•mol−1 for each additional methylene group, whereas 4 and 5 are approximately equipotent. Surprisingly, the affinity enhancements for the series 1–4 are a consequence of increasingly more favorable binding enthalpies that dominate increasingly less favorable changes in binding entropies. These data thus reflect an enthalpy-driven hydrophobic effect, which has been documented in host-guest systems,12 but we are aware of only one such case involving a series of homologous ligands in protein-ligand interactions.8 Balancing enthalpy-entropy compensation is evident for the 6- and 7-membered ring analogs 4 and 5. The negative values for the change in heat capacity (ΔCp) for 1–5 (Table 1) are in accord with burial of nonpolar surfaces on binding,7,13 but there is no direct relationship between the magnitude of ΔCp and the number of methylene groups in the ring. These data suggest that dissimilarities in desolvation might contribute to differential binding energetics of 1 and 3 relative to 2, 4, and 5.13

Table 1.

Thermodynamic data and summary of polar and nonpolar contacts for complexes of 1–5 and the Grb2 SH2 domain.[a,b]

| Ligand | Ka (× 105 M−1) | ΔG° (kcal•mol−1) | ΔH° (kcal•mol−1) | −TΔS° (kcal•mol−1) | ΔCp (cal•mol−1K−1) | Total Polar Contacts[c] | pTyr +1 VDW contacts[d] | ΔCSAnp (Å2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Water-mediated | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | −7.1 ± 0.1 | −3.3 ± 0.3 | −3.8 ± 0.1 | −116 ± 12 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 176 |

| 2 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | −7.7 ± 0.1 | −5.4 ± 0.3 | −2.3 ± 0.2 | −185 ± 8 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 178 |

| 3 | 16.1 ± 1.1 | −8.5 ± 0.1 | −6.3 ± 0.4 | −2.2 ± 0.2 | −141 ± 8 | 14 | 4 | 9 | 197 |

| 4 | 69.6 ± 12.0 | −9.3 ± 0.1 | −8.5 ± 0.4 | −0.8 ± 0.4 | −181 ± 10 | 14 | 5 | 13 | 213 |

| 5 | 37.0 ± 3.3 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | −6.8 ± 0.3 | −2.1 ± 0.2 | −173 ± 8 | 14 | 5 | 14 | 202 |

ITC experiments were conducted at 25 °C in HEPES (50 mM) with NaCl (150 mM) at pH 7.45 ± 0.05 as previously reported.6b

Three or more experiments were performed for each ligand, and the averages are reported following normalization of the n values for each experiment by adjusting ligand concentration (See Supporting Information). Errors in the thermodynamic values were determined by the method of Krishnamurthy.15

Total direct and single water-mediated hydrogen bonding contacts between protein and ligand for which non-hydrogen donor-acceptor distances are within the range 2.5–3.5 Å.

A hydrophobic VDW contact exists when the interatomic distance between a methylene group in the pTyr+1 residue and a carbon, nitrogen, or oxygen atom in the domain is in the range of 3.4–4.2 Å.

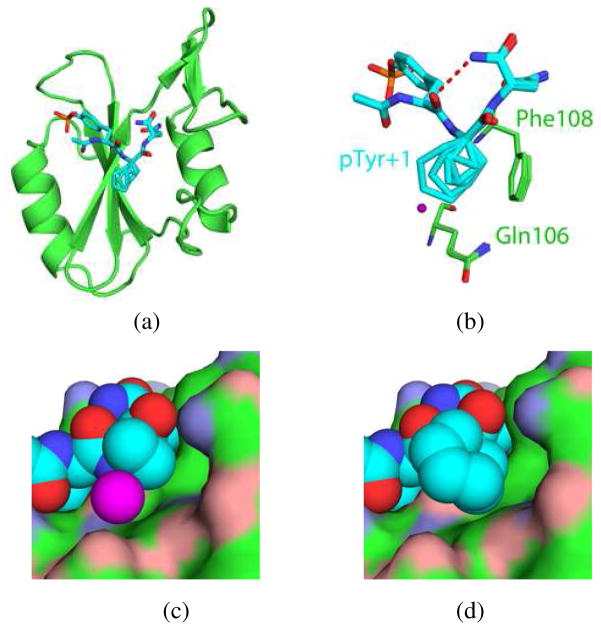

The structures of complexes of the Grb2 SH2 domain with 1–5 were determined by X-ray crystallography at resolutions of 1.6–1.8 Å.14 Alignment of the backbone atoms belonging to the domain in the complex of 1 with those in each of the other four complexes yields root mean square deviations (RMSDs) for all backbone atoms of <0.2 Å (Figure 1a). Because these RMSDs are less than the coordinate error that is associated with the molecular models,16 variations in the backbone of the domains are not considered significant. Each of the ligands 1–5 binds to the domain in a turned conformation in which there is an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen atom of the pTyr residue and the C-terminal amide functional group of the Asn residue. All atoms in the pTyr and pTyr+2 residues of 1–5 align with RMSDs of <0.2 Å, and only those carbon atoms in the cycloaliphatic rings of the pTyr+1 residue vary significantly in position. The τ bond angle (i.e., NH–Cα–C) of the pTyr+1 residue is 109.5° (±2.0°) in ligands 2–5, but it is 116° in 1 because of the cyclopropane ring. However, the structural data reveal that this difference is neither reflected in observable variations in the spatial orientations of atoms in the pTyr and pTyr+2 residues of 1 nor in its interactions with the domain relative to other ligands.

Figure 1.

(a) Overlay of complexes of the Grb2 SH2 domain with 1–5. Oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorous atoms are colored red, blue, and orange, respectively. Carbon atoms belonging to the ligands (sticks) are colored cyan while those belonging to the domain (cartoon) are colored green. (b) Overlay of 1–5 (sticks) showing side chains of domain residues Glu106 and Phe108 (sticks) involved in VDW contacts. Water molecule (purple sphere) is present only in complex of 1. (c) and (d) Compounds 1 and 5, respectively, which are represented as discreet spheres corresponding to atomic VDW radii, bound to the Grb2 SH2 domain, which is represented by a continuous VDW surface to depict the extent to which methylene groups at the pTyr+1 position interact with residues of the domain. Oxygen and nitrogen atoms are colored red and blue, respectively, with those belonging to the ligand a darker hue than those belonging to the domain. Carbon atoms belonging to the ligand are colored cyan while those belonging to the domain are colored green. Water molecule (purple sphere) in (c) is present only in the complex of 1.

An analysis of nonbonded, polar contacts within the range of 2.5–3.5 Å between non-hydrogen donor and acceptor atoms in the complexes of 1–5 shows that the number of direct contacts between the ligands and the domain is the same (Table 1). The number of single water mediated contacts for 1, 4, and 5 are also identical, but because the complexes of 2 and 3 have two and one fewer interfacial water molecules in the vicinity of the pTyr+2 residue, respectively, there are correspondingly fewer single water mediated contacts in these complexes. Fixing a water molecule at the protein-ligand interface should have an unfavorable entropic consequence,17 so one might anticipate forming complexes with fewer interfacial water molecules would enjoy an entropic benefit. However, any such advantage is not apparent upon comparing the relative –TΔS° terms for the complexes. The other notable difference in water structure is the presence of an ordered water molecule ca. 3.6 Å removed from the Cβ atoms of the cyclopropyl ring in the complex of 1 that is absent in other complexes (Figure 1b,c). Although this water molecule does not mediate any protein-ligand interaction, its presence might be expected to incur an entropic penalty, but again this is not reflected in the relative binding entropy of 1, which is the most favorable of all ligands. There is thus no obvious correlation between the relative number of interfacial water molecules and binding entropies. However, because disordered water molecules may not be visible by crystallography, correlating the number of interfacial water molecules with variations in thermodynamic parameters is problematic. A more detailed water analysis is precluded by lack of a structure of the apo Grb2 SH2 domain, which invariably forms a domain-swapped dimer upon crystallization.18

We inventoried van der Waals (VDW) contacts using the distance criteria of 3.4–4.2 Å for nonbonded atoms.19 The number of VDW contacts between the domain and the pTyr and pTyr+2 residues for each ligand is identical, whereas the number of VDW contacts between Gln106, His107, and Phe108 of the domain and the ring at the pTyr+1 site increases with ring size (cf. Figures 1b–d; see also Supporting Information). For example, the Cγ atom in the cycloaliphatic ring at the pTyr+1 subsites of 3–5 makes VDW contacts with the aromatic ring of Phe108 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of His107; these interactions are not possible for 1 and 2. The Cδ atom in the rings at the pTyr+1 subsites of 4 and 5 make two and four VDW contacts, respectively, with the side chain of Gln106.

Having thermodynamic and structural data for the series of complexes of 1–5 with the Grb2 SH2 domain provides an opportunity to correlate structural features such as buried nonpolar and polar Connolly surface area (CSA)20 with changes in the energetic parameters that are associated with complexation. In the present instance, however, such correlations are subject to some uncertainties because the calculated ΔCSAnp and ΔCSAp values are based upon structures of the complexes; there is no structure of the apo form of the monomeric Grb2 SH2 domain (vide supra). Accordingly, ΔCSAnp values were calculated using the X-ray structures of the complexes with ligands 1–5 removed as a proxy for the apo protein. The bound conformations of the ligands were then taken as being representative of the ensemble of their preferred solution structures. Although there is no correlation of ΔCp with either ΔCSAnp or ΔCSAp, there are correlations between ΔCSAnp and ΔG° (R2 = 0.96) and ΔH° (R2 = 0.87). The dependence of ΔG° on ΔCSAnp for 1–5 corresponds to a contribution of –56 ± 7 cal•mol−1Å−2, a value significantly larger than the –12 cal•mol−1Å−2 that is obtained from the analysis of a large number of different protein-ligand complexes.3 The dependence of ΔH° on ΔCSAnp in these enthalpy-driven associations is –114 ± 25 cal•mol−1Å−2. There is no correlation of any energetic parameter with ΔCSAp.

Introducing methylene groups at the pTyr+1 position of the phosphotyrosine-derived peptide 1 gave compounds having increased potency for the Grb2 SH2 domain, but this enhancement was a consequence of more favorable binding enthalpies, not the more favorable entropies that would be expected based upon the “classical” hydrophobic effect. These experiments thus underscore the complexities associated with correlating structural changes in a ligand with protein binding thermodynamics. One problem is that little is known about how altering a ligand affects its structure, dynamics, and energetics in solution. For example, the α, α-cycloaliphatic amino acids at the pTyr+1 position of 1–5 should favor turned conformations in solution,21 but the consequent contributions to binding entropy associated with this preorganization cannot be easily estimated.6 The strain energies associated with the unbound and bound forms of 1–5 will also vary, but correlating the effects of such differences upon relative binding energetics is difficult.22 Although there are no notable variations in protein structure in the complexes in the solid state, there may be differences in backbone conformations and dynamics in solution, as has been observed for selected complexes of HIV-1 protease23 and major urinary protein (MUP).24 Dissimilarities in protein flexibility in complexes of a protein with different ligands will be accompanied by changes in nonbonded interactions and order that should be reflected in relative binding enthalpies and entropies.25 However, whether differential variations in protein dynamics are energetically consequential is unknown.6a,b Finally, the energetic effects of solvent reorganization in protein-ligand interactions are poorly understood.

In summary, the binding affinities of 1–5, which incorporate α, α-cycloaliphatic amino acids at the pTyr+1 site, for the Grb2 SH2 domain increase incrementally with ring size up to a maximal affinity for the six-membered ring analog 4, which is approximately equipotent to the seven-membered ring analog 5. This increase in affinity correlates with the burial of nonpolar surface area with a dependence of ΔG° on ΔCSAnp of –56 ± 7 cal•mol−1Å−2. In contrast to what is commonly assumed for protein-ligand interactions, the enhanced potency that accompanies adding methylene groups for 1–4 is a consequence of increasingly more favorable binding enthalpies that dominate increasingly unfavorable binding entropies. Although there are differences in the number of interfacial water molecules in the complexes of 1–5, these variations are not evident in the relative binding entropies. These studies also show that there is no obligatory correlation of ΔCp with buried nonpolar surface area. These findings highlight the fallibilities of some prevailing views of structure and energetics in protein-ligand interactions. In particular they reveal the challenges presently inherent in correlating specific changes in ligand structure with observable contributions to protein binding enthalpies and entropies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM 84965), the National Science Foundation (CHE 0750329), the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-652), and the Norman Hackerman Advanced Research Program for their generous support of this research. J.E.D. thanks the ACS Division of Medicinal Chemistry and Pfizer, Inc., as well as the Dorothy B. Banks Foundation for predoctoral fellowships. We also thank Ms. Andrea Beckham and Ms. Abby Coldren for experimental and technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Methods and materials for ITC and X-ray crystallographic experiments, X-ray diffraction statistics, electron density difference maps, contact diagrams and VDW surface representations, surface area calculations, and plots of crystallographic and thermodynamic data are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For some reviews and lead references, see: Gohlke H, Klebe G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2644–2676. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020802)41:15<2644::AID-ANIE2644>3.0.CO;2-O.Hunter CA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5310–5324. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301739.Warren GL, Andrews CW, Capelli AM, Clarke B, LaLonde J, Lambert MH, Lindvall M, Nevins N, Semus SF, Senger S, Tedesco G, Wall ID, Woolven JM, Peishoff CE, Head MS. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5912–5931. doi: 10.1021/jm050362n.Mobley DL, Dill KA. Structure. 2009;17:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.02.010.Freire EA. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00880.x.Ladbury JE, Klebe G, Freire E. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:23–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd3054.

- 2.Reynolds CH, Holloway MK. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:433–437. doi: 10.1021/ml200010k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For lead references to thermodynamic data in protein-ligand interactions, see: Olsson TSG, Williams MA, Pitt WR, Ladbury JE. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:1002–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.073.

- 4.(a) Dunitz JD. Chem Biol. 1995;2:709–712. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lafont V, Armstrong AA, Ohtaka H, Kiso Y, Amzel LM, Freire E. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;69:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson JP, Lubman O, Rose T, Waksman G, Martin SF. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:205–215. doi: 10.1021/ja011746f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Benfield AP, Teresk MG, Plake HR, DeLorbe JE, Millspaugh LE, Martin SF. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6830–6835. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DeLorbe JE, Clements JH, Teresk MG, Benfield AP, Plake HR, Millspaugh LE, Martin SF. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16758–16770. doi: 10.1021/ja904698q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) DeLorbe JE, Clements JH, Whiddon BB, Martin SF. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:448–452. doi: 10.1021/ml100142y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Kyte J. Biophys Chem. 2003;100:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dill KA, Truskett TM, Vlachy V, Hribar-Lee B. Ann Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:173–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chandler D. Nature. 2005;437:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malham R, Johnstone S, Bingham RJ, Barratt E, Phillips SEV, Laughton CA, Homans SW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17061–17067. doi: 10.1021/ja055454g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey C, Cheng YK, Rossky P. Chem Phys. 2000;258:415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For a review of SH2 domains, see: Bradshaw JM, Waksman G. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;61:161–210. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)61005-8.

- 11.García-Echeverría C, Gay B, Rahuel J, Furet P. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2915–2920. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For a review, see: Meyer EA, Castellano RK, Diederich F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;43:1210–1250. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390319.

- 13.(a) Sturtevant JM. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2236–2240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Privalov PL, Gill SJ. Adv Protein Chem. 1988;39:191–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Connelly PR, Thomson JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4781–4785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Loladze VV, Ermolenko DN, Makhatadze GI. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1343–1352. doi: 10.1110/ps.370101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coordinates and structure factors for the complexes of 1–5 have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank as entries 3OV1, 3S8L, 3S8N, 3S8O, and 3OVE, respectively.

- 15.Krishnamurthy VM, Bohal BR, Semetey V, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5802–5812. doi: 10.1021/ja060070r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luzzati V. Acta Cryst. 1952;5:802–810. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunitz JD. Science. 1994;264:670. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5159.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benfield AP, Whiddon BB, Clements JH, Martin SF. Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li AJ, Nussinov R. Proteins. 1998;32:111–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The molecular or Connolly surface area (CSA) has been shown to be a better model for estimating hydrophobic effects than the accessible molecular or solvent accessible surface (ASA). See: Tuñón I, Silla E, Pascual-Ahjuir JL. Protein Eng. 1992;5:715–716. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.8.715.

- 21.Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers. 2001;60:396–419. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perola E, Charifson PS. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2499–2510. doi: 10.1021/jm030563w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackburn ME, Veloro AM, Fanucci GE. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8765–8767. doi: 10.1021/bi901201q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For x-ray and NMR structural data of MUP, see: Zidek L, Novotny MV, Stone MJ. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1118–1121. doi: 10.1038/70057.Timm DE, Baker LJ, Mueller H, Zidek L, Novotny MV. Protein Sci. 2001;10:997–1004. doi: 10.1110/ps.52201.Bingham RJ, Findlay JHBC, Hsieh SY, Kalverda AP, Kjellberg A, Perazzolo C, Phillips SEV, Seshadri K, Trinh CH, Turnbull WB, Bodenhausen G, Homans SW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1675–1681. doi: 10.1021/ja038461i.Barratt E, Bingham RJ, Warner DJ, Laughton CA, Phillips SEV, Homans SW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11827–11834. doi: 10.1021/ja0527525.Pertinhez TA, Ferari E, Casali E, Patel JA, Spisni A, Smith LJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1266–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.133.

- 25.For some leading references, see: Kay LE, Muhandiram DR, Wolf G, Shoelson SE, Forman-Kay JD. Nature Struct Biol. 1998;5:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-156.Engen JR, Gmeiner WH, Smithgall TE, Smith DL. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8926–8935. doi: 10.1021/bi982611y.Stone MJ. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:379–388. doi: 10.1021/ar000079c.Ferreon JC, Hilser VJ. Protein Sci. 2003;12:982–996. doi: 10.1110/ps.0238003.Williams DH, Stephens E, O’Brien DP, Zhou M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6596–6616. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300644. and references therein.de Mol NJ, Catalina MI, Fischer MJE, Broutin I, Maier CS, Heck AJR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1700:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.03.016.MacRaild C, Daranas H, Bronowska A, Homans SW. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.055.Marlow MS, Dogan J, Frederick KK, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. Nature Chem Biol. 2010;6:352–358. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.347.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.