Abstract

The hormones auxin and cytokinin are key regulators of plant growth and development. As they are active at minute concentrations and regulate dynamic processes, cell and tissue levels of the hormones are finely controlled developmentally, diurnally, and in response to environmental variables. This fine control, along with a regulation of the capacity to respond ensures that the appropriate type, duration and intensity of responses are elicited. We have recently discovered that cytokinin and auxin regulate the synthesis of each other, demonstrating a mechanism for mutual feed back and feed forward control of auxin and cytokinin levels. This regulatory loop could be important for many developmental processes in plants, i.e., in fine-tuning plant hormone levels in the developing meristems of the root and shoot apex. These findings could also give a molecular explanation for earlier observations of auxin and cytokinin effects on cell cultures,1 where specific auxin and cytokinin ratios have been used to trigger different morphological events.

Key words: auxin, cytokinin, biosynthesis, metabolism, signaling, root development, interactions

Regulation of Auxin and Cytokinin Biosynthesis and Degradation—Where, When and How?

The plant hormones auxin and cytokinin are important for almost all aspects of plant growth and development. They can act synergistically or antagonistically, depending on the context and their respective levels. Mechanisms that regulate the synthesis and breakdown of both classes of compounds are likely to be very important for different developmental processes.2

Auxin biosynthesis and degradation.

Compared to other classic plant hormones, comparatively little is known about the molecular basis of auxin biosynthesis. In part, this is because of difficulties arising from the existence of multiple auxin biosynthesis pathways and the high level of redundancy between these pathways.3,4 The most well characterized IAA biosynthesis pathways have the amino acid tryptophan as a common precursor, with indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx), tryptamine (TRM) and indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPA) as intermediates.4 The last biosynthetic step has been suggested to be the conversion of either indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) or indole-3-acetaldehyde (IAAld) to IAA. The biosynthesis of tryptophan is believed to be plastid localized,3,5 while most data suggests that Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis takes place in the cytoplasm3 (Fig. 1). The large redundancy in the IAA biosynthesis pathways has been a puzzle, but recent data suggests that the different pathways might be involved in specific developmental processes, such as shade avoidance (IPA pathway), embryogenesis (IPA/TRM pathways), flower and fruit development (TRM pathway) and root development (Trp, IPA and IAOx pathways).2,4

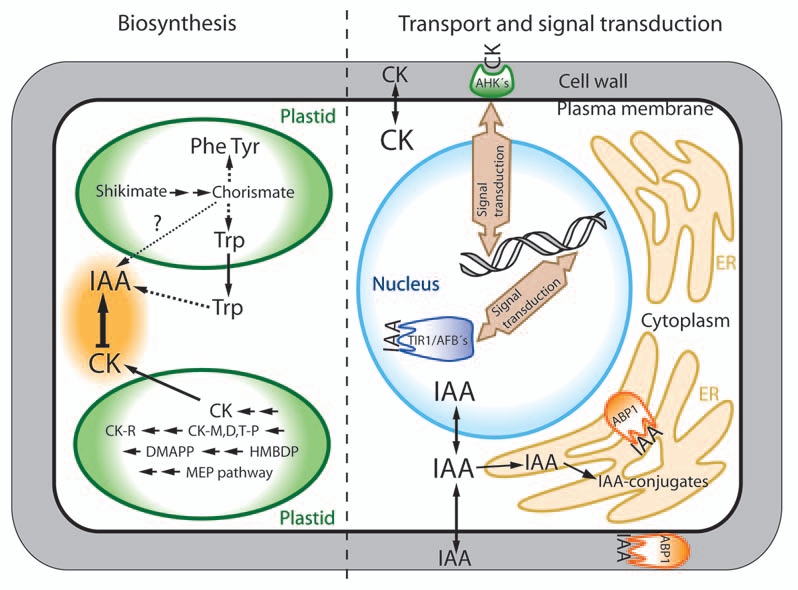

Figure 1.

Subcellular localization of auxin (IAA) and cytokinin (CK) metabolism, transport and signaling in Arabidopsis. IAA and CK biosynthesis. Biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids, including tryptophan, is located to plastids, while the final steps in IAA biosynthesis is believed to take place in the cytoplasm. CKs are biosynthesized in plastids and then transported to the cytoplasm. IAA downregulates CK biosynthesis,12 while CK on the other hand induces IAA biosynthesis.13 IAA and CK transport and signaling. IAA binds to the nuclear IAA receptors (TIR1/AFB's) and to Aux/IAA proteins that are subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome complex. The AuxIAA proteins interact with ARF transcription factors to regulate gene transcription.19 The other putative IAA receptor (ABP1) is located both to the plasma membrane and to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where a part of the intracellular IAA pool is located as IAA amino acid conjugates.7 The CK receptors (AHKs) are also located to the plasma membrane, while AHP and ARR proteins transmit the CK signal to the nucleus.20 Both IAA and CK are actively transported across the plasma membrane. ABP1, auxin-binding protein 1; AFB, auxin F box; AHK, Arabidopsis histidine kinase; AHP, Arabidopsis histidine phosphotransfer proteins; ARF, auxin response factor; ARR, Arabidopsis response regulators; Aux/IAA, auxin/indole-3-acetic acid; CK-M,D,T-P, cytokinin-mono,di,tri-phosphates; CK-R, cytokinin ribosides; DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate; HMBDP, hydroxymethylbutenyl diphosphate; MEP, methylerythritolphosphate; Phe, phenylalanine; TIR1, transport inhibitor resistant 1; Trp, tryptophan; Tyr, tyrosine.

How IAA levels are actively reduced in cells is less well defined. It is known, however, that IAA is actively degraded by oxidation to oxIAA (the major catabolite in Arabidopsis) and conjugated to amino acids or sugars.3,4,6 Recent data suggests that a part of the pool of cytosolic IAA can be transported to the endoplasmic reticulum, where it can be conjugated to amino acids for storage and/or degradation.7 The subcellular localization of oxIAA formation is still unknown, and none of the enzymes involved in the oxIAA pathway have been identified.

Cytokinin biosynthesis and degradation.

The early steps in cytokinin biosynthesis (formation of the isoprenoid side chain and biosynthesis of iP-type cytokinins by adenosine phosphate-isopentenyl-transferases, IPTs) appear to be located in plastids, but the location of biosynthesis of active cytokinins and cytokinin conjugates is largely unknown.8 The last steps in the biosynthesis of active cytokinins involve CYP735A conversion of iP to tZ cytokinins and the conversion of cytokinin ribotides and ribosides to the active cytokinins via the LOG genes.9 Gene expression data from the CYP735A, IPT and LOG genes indicate that cytokinin biosynthesis is highly cell and tissue specific.2,8,10

Like auxin, steady-state levels of cytokinin are regulated by their inactivation through conjugation and degradation. Cytokinins can be inactivated by glucosylation of the purine moiety (N-glucosides) or the side chain hydroxyl group (O-glucosides or O-xylosides).8 β-glucosidase readily catalyzes the removal of the O-glucosyl group, suggesting that O-glucosylation produces a reversible storage form of the hormone. In contrast, N-glucosides are not readily cleaved, indicating that N-glucosylation leads to terminal inactivation of the hormone. Cytokinin is also degraded by side chain cleavage through the action of the cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX) family of enzymes.11

Mechanisms Behind Auxin Cytokinin Interactions at the Metabolic Level

Recent insights into the mechanisms behind auxin and cytokinin metabolism have led to the conclusions that (1) one can assume that both auxin and cytokinin biosynthesis often take place in the same cells/tissues in the plant (2) there are multiple points for interactions at the metabolic level and (3) metabolic, as well as receptor and signal transduction gene redundancy is likely to be involved in cell and tissue specificity of responses.

Previous work from our group demonstrated that auxin can induce a rapid downregulation of cytokinin biosynthesis.12 We were then able to show that in root tips and young, developing shoot tissues, where both auxin and cytokinin play critical regulatory roles, ectopic cytokinin rapidly initiates an increase in auxin biosynthesis.13 Others have shown that cytokinin can alter auxin responses by regulating the expression of genes involved in auxin signaling and transport.14,15 The discovery that both hormones play a role in the metabolic control in each other's biosynthesis further illustrates the complexity and depth of the interrelationship between the two hormones. In our most recent work, in addition to finding that an ectopic increase in cytokinin leads to an increase in the rate of auxin biosynthesis, we found that decreasing endogenous cytokinin levels reduces the rate of auxin biosynthesis. Together these data provide strong evidence for the role of cytokinin in maintaining appropriate levels of auxin biosynthesis. They also indicate the critical importance of the homeostatic control of appropriate auxin and cytokinin ratios to plant function.

Through both microarrays and Q RT-PCR we have been able to identify many auxin metabolic genes that are regulated by cytokinin in root tips.13 These include those encoding the tryptophan biosynthesis enzymes, ASA1/WE12, PAT/TRP1 and IGPS; the IAOx biosynthetic enzymes, CYP79B2, CYP79B3, YUCCA5, YUCCA6 and YUCCA5-like; the IPA biosynthetic enzyme TAA1; and the NIT1 and NIT3 enzymes that catalyze the final step in auxin biosynthesis, conversion of indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) to IAA. Transcript levels for the IAA conjugating enzymes GH3.17 and GH3.9 were also found to be affected by cytokinin.

These data show that in root tips, cytokinin regulates several different auxin biosynthetic pathways at multiple points in the pathways. An examination of the extensive microarray data on the Genevestigator website16 indicated that in addition to the genes that we have identified in the root apex, there is evidence that a number of other genes throughout the plant are involved in the feedback metabolic control that regulates relative levels of auxin and cytokinin (Figs. 2 and 3). Considerable evidence has accumulated that active transport is a necessary regulator of hormone levels in important tissues such as the apical meristems.17 Our data highlight two other mechanisms, in situ de novo biosynthesis18 and the cross-regulation of auxin and cytokinin hormone levels13 that work alongside transport to establish and maintain appropriate levels of these key hormones during growth and development.

Figure 2.

Genes involved in auxin metabolism differentially expressed in response to altered cytokinin levels and/or responsiveness in Arabidopsis. The Genevestigator Microarray Database16 was used to identify auxin metabolic genes that were affected by experimental conditions where cytokinin levels and/or responsiveness were manipulated. AT5G43890 (YUCCA5) and AT1G04180 (YUCCA9) Flavin monooxygenases;2 AT1G23320 (TAR1) Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent aminotransferase;21 AT1G23160, (GH3-7), AT1G48670 (GH3-18), AT1G48690 (GH3-20), AT2G23170 (GH3-3) and AT5G51470 (GH3-8) IAA amino acid conjugation GH3 family proteins.22 GV Exp. Key, Genevestigator experiment identification number.

Figure 3.

Genes involved in cytokinin metabolism differentially expressed in response to altered auxin levels and/or responsiveness in Arabidopsis. The Genevestigator Microarray Database16 was used to identify cytokinin metabolic genes that were affected by experimental conditions where auxin levels and/or responsiveness were manipulated. At5g26140 (LOG9) Cytokinin nucleoside 5′-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase;10 At2g41510 (CKX1) and At3g63440 (CKX6) Cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenases;11 At2g36750 (UGT73C1) Zeatin-O-glucosyltransferase.8 GV Exp. Key, Genevestigator experiment identification number.

References

- 1.Skoog F, Miller CO. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;11:118–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y. The role of local biosynthesis of auxin and cytokinin in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: Regulation, action and interaction. Annals Bot. 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Normanly J. Approaching cellular and molecular resolution of auxin biosynthesis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:1594. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzin V, Galili G. New insights into the shikimate and aromatic amino acids biosynthesis pathways in plants. Mol Plant. 2010;3:956–972. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowalczyk M, Sandberg G. Quantitative analysis of indole-3-acetic acid metabolites in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1845–1853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mravec J, Skupa P, Bailly A, Hoyerová K, Krecek P, Bielach A, et al. Subcellular homeostasis of phytohormone auxin is mediated by the ER-localized PIN5 transporter. Nature. 2009;459:1136–1140. doi: 10.1038/nature08066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakakibara H. Cytokinins: Activity, biosynthesis and translocation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamada-Nobusada T, Sakakibara H. Molecular basis for cytokinin biosynthesis. Phytochem. 2009;70:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroha T, Tokunaga H, Kojima M, Ueda N, Ishida T, Nagawa S, et al. Functional analysis of LONELY GUY cytokinin-activating enzymes reveal the importance of the direct activation pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3152–3169. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmülling T, Werner T, Riefler M, Krupková E, Bartrina y Manns I. Structure and function of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase genes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis and other species. J Plant Res. 2003;116:241–252. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordström A, Tarkowski P, Tarkowska D, Norbaek R, Åstot C, Dolezal K, et al. Auxin regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana: A factor of potential importance for auxin-cytokinin-regulated development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8039–8044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402504101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones B, Andersson Gunnerås S, Petersson SV, Tarkowski P, Graham N, May S, et al. Cytokinin regulation of auxin synthesis in Arabidopsis involves a homeostatic feedback loop regulated via auxin and cytokinin signal transduction. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2956–2969. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dello Ioio R, Nakamura K, Moubayidin L, Perilli S, Taniguchi M, Morita MT, et al. A genetic framework for the control of cell division and differentiation in the root meristem. Science. 2008;322:1380–1384. doi: 10.1126/science.1164147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruzicka K, Simásková M, Duclercq J, Petrásek J, Zazímalová E, Simon S, et al. Cytokinin regulates root meristem activity via modulation of the polar auxin transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4284–4289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, et al. Genevestigator V3: A reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Advances in Bioinformatics. 2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisniewska J, Xu J, Seifertová D, Brewer P, Ruzicka K, Blilou I, et al. Polar PIN localization directs auxin flow in plants. Science. 2006;312:883. doi: 10.1126/science.1121356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersson SV, Johansson AI, Kowalczyk M, Makoveychuk A, Wang JY, Moritz T, et al. An auxin gradient and maximum in the Arabidopsis root apex shown by high-resolution cell-specific analysis of IAA distribution and synthesis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1659–1668. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman EJ, Estelle M. Mechanism of auxin-regulated gene expression in plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:265–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To JP, Kieber JJ. Cytokinin signaling: two-components and more. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stepanova AN, Robertson-Hoyt J, Yun J, Benavente LM, Xie DY, Doležal K, et al. TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell. 2008;133:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takase T, Nakazawa M, Ishikawa A, Manabe K, Matsui M. DFL2, a new member of the Arabidopsis GH3 gene family, is involved in red light-specific hypocotyl elongation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]