Abstract

C. elegans RDE-4 is a double-stranded RNA binding protein that has been shown to play a key role in response to foreign double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). We have used diverse tools for analysis of gene function to characterize the domain and organismal foci of RDE-4 action in C. elegans. First, we examined the focus of activity within the RDE-4 protein, by testing a series of RDE-4 deletion constructs for their ability to support dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. These assays indicated a molecular requirement for a linker region and the second dsRNA-binding domain of RDE-4, with ancillary contributions to function from the C and N terminal domains. Second, we used mosaic analysis to explore the cellular focus of action of RDE-4. These experiments indicated an ability of RDE-4 to function non-autonomously in foreign RNA responses. Third, we used growth under stressful conditions to search for evidence of an organismal focus of action for RDE-4 distinct from its role in response to foreign dsRNA. Propagation at high temperatures exposed a conditional requirement for RDE-4 for optimal growth and fertility, indicating at least under these conditions that RDE-4 can serve an essential role in C. elegans.

Key words: RDE-4, C. elegans, small RNA, RNAi, autonomy, dicer, temperature-sensitive, domain, dsRNA, silencing

Introduction

The RNA interference (RNAi) pathway uses short RNA effectors of length ∼19–30 nt to regulate gene expression in organisms as diverse as plants, fungi, worms, insects and mammals.1–6 RNAi is involved in the cellular and organismal response to foreign agents such as nucleic acids and pathogens,7 and in the regulation of endogenous gene expression for maintaining genome integrity and proper cellular functions.3,8

dsRNA is a potent trigger for RNAi. In C. elegans, naked foreign dsRNA or dsRNA generated by viral agents is recognized by a complex containing the dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 (“RDE” refers to RNAi Defective, to denote the phenotype of animals lacking the protein) and the endonuclease DICER1 (DCR-1).9–14 RDE-4 consists of two dsRNA binding domains (dsRBD1 and dsRBD2; Fig. 1) separated by a “linker” region and flanked by N and C terminal domains.13 The products of RDE-4/DCR-1 cleavage on long dsRNA templates are smaller dsRNA fragments called primary short interfering RNAs (siRNAs).12,13 rde-4 mutants are impaired in their ability to produce siRNAs from an injected dsRNA substrate and to initiate heritable silencing signals.12,15

Figure 1.

RDE-4 domains, and description of rde-4 mutations and deletion constructs. Domains of RDE-4 are represented schematically. Black arrows delineate amino acids at domain boundaries, while red arrows indicate mutations that define the ne299 and ne337 alleles. Amino acids deleted in truncated versions of RDE-4 are preceded by “Δ.”

In vitro, RDE-4 binds long dsRNA with high affinity, but has much reduced affinity for short dsRNAs and siRNAs,11 and does not appear to bind ssRNA targets.13 dsRBD2 is absolutely required for binding long dsRNA,11 and both dsRBD2 and linker regions are required for reconstituting dicer activity on long dsRNA in C. elegans extracts.11

Although rde-4 mutants show substantial decreases in their response to long dsRNA triggers,16 the requirement of RDE-4 for RNAi in vivo is not absolute. First, these mutants are sensitive to short dsRNA triggers.12 Second, an excess supply of dsRNA can bypass the requirement for RDE-4 through a pathway that includes RDE-1.17 Finally, an exogenous supply of antisense siRNAs can bypass the requirement for RDE-4.18

Analyses of RNA sequence populations in normal and rde-4 mutant animals have suggested additional roles for RDE-4 in generating specific populations of small RNAs corresponding to endogenous genes.19–21 In several such studies, RDE-4, together with members of the ERI/Dicer complex (ERI: Enhanced RNAi), has been shown to function in generating a set of 26-base 5′-pG siRNAs.19,21 Recent reports have also described an operational interplay between the RDE-4 complex and a set of additional cellular machineries (the nuclear transcriptional gene silencing response,22 ADAR-based RNA editing,23 and germline development mediated by P granules24). While many players in these pathways exhibit severe defects in development that include lethality and sterility,25–28 reported defects exhibited by RDE-4 mutants are limited to the RNAi deficiencies and a decrease in post-reproductive lifespan.29

In this paper, we use in vivo dsRNA trigger delivery assays to address questions pertaining to molecular and spatial requirements for RDE-4's role in RNAi, and an organismal temperature stress assay to probe for RDE-4's role in developmental pathways.

Results

RDE-4 domain requirements in response to injected dsRNA.

Starting in a genetic background in which the rde-4 gene carried a stop codon [rde-4(ne299)] we transformed C. elegans with a series of transgene constructs with distinct deletions and truncations of rde-4. Several independent transgenic lines from each primary deletion were obtained. The resulting transgenic lines were then each injected with a dsRNA trigger derived from the C. elegans unc-22 locus. In RNAi-competent animals, this RNAi intervention results in a distinctive Unc-22 “twitching” phenotype.16 Following dsRNA injection into adult transgenic animals, numbers of twitching individuals were assayed in each progeny brood (Table 1), both quantitatively (counting twitching animals in individual experiments) and en masse (by observing populations of animals). The combination of assays was of considerable utility, as individual injections are subject to some variability in delivery and recovery.30 unc-22 phenotypes are accentuated in the presence of the acetylcholine analog levamisole,31 and this drug was included in assays where noted (Table 1).

Table 1.

RNAi sensitivity of rde-4 deficient worms rescued with full-length and truncated rde-4 constructs (trigger: injected dsRNA)

| Name of construct | Domains retained in construct | Qualitative results | Quantitative results | ||||||||

| N-term | dsRBD1 | Spacer | dsRBD2 | C-term | n | (Line) +Lev | (Line) −Lev | +Lev (Line) Twitchers: Non-Twitchers | −Lev (Line) Twitchers: Non-Twitchers | ||

| N2* | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | ++ | ++ | (NA) 1607:145 | ND | |

| pha-1** | − | − | − | − | − | 1 | N/D | N/D | (DI292c) 1:31 (DI292e) 11:359 (DI292f) 4:307 (DI292g) 2:112 |

ND | |

| rde-4 full-length | + | + | + | + | + | 3 | (DI41a)++ (DI41c)++ |

(DI41a)++ (DI41c)++ |

(DI41a) 91:19 (DI41a) 234:22 (DI41d) 33:5 |

ND | |

| ΔNterm | − | + | + | + | + | 2 | (DI42b)+ | (DI42b)− | (DI42a) 12:176 (DI42c) 11:224 (DI42d) 6:199 |

ND | |

| Δ(Nterm, dsRBD1) | − | − | + | + | + | 1 | ND | ND | (DI90a) 64:66 (DI90c) 67:79 |

ND | |

| ΔdsRBD1 | + | − | + | + | + | 3 | (DI38a)++ (DI38b)++ |

(DI38a)+ (DI38b)++ |

(DI38b) 96:36 | (DI38b) 28:74 | |

| ΔSpacer | + | + | − | + | + | 2 | (DI39b)− | (DI39b)− | (DI39a) 2:71 | (DI39a) 0:112 | |

| ΔdsRBD2 | + | + | + | − | + | 3 | (DI40b)− (DI40c)− |

(DI40b)− (DI40c)− |

(DI40a) 2:72 | (DI40a) 0:74 | |

| ΔCterm^ | + | + | + | + | − | 2 | N/D | N/D | (DI89a) 56:49 (DI294a) 43:170 (DI294d) 8:108 |

(DI89a) 14:94 (DI41a) 106:15 |

|

| Δ(Nterm, Cterm) | − | + | + | + | − | 1 | (DI67a)− | (DI67a)− | ND | ND | |

| +(dsRBD2) | − | − | − | + | − | 1 | (DI68a)− (DI68b)− |

(DI68a)− (DI68b)− |

ND | ND | |

| +(Spacer, dsRBD2) | − | − | + | + | − | 1 | (DI69a)+ (DI69b)+ |

(DI69a)− (DI69b)− |

ND | ND | |

rde-4(ne299)pha-1(e2123ts) mutant animals were transformed with a mixture containing one of various myo3::rde-4 constructs, and pha-1(+) as a marker for selecting transgenic worms. Independently derived lines of transgenic worms (denoted by “DIxy,” where x is a number that identifies the strain, and y is a lower case letter that identifies individual lines derived from the same strain) were subsequently injected with dsRNA against unc-22 to measure twitching behavior both in the absence and presence of levamisole (a drug that enhances twitching behavior), with strong twitching being an indicator of functional RNAi. Twitching behavior was classified as per the following criteria: ++Strong, clear twitching in a majority of animals. These animals are unable to maintain a muscular contraction and undergo visible spasms when attempting to move. +Clear twitching in greater than 50% of animals. −+Moderate-to-mild twitching in greater than 40% of animals. −No, or very little twitching in less than 10% of animals. n, Number of experiments. *Injections performed in N2 worms. **Injected construct: rde-4(ne299); pha-1. ^Construct encodes for RDE-4 fused to an N-terminal GFP.

Under these conditions, we observed a twitching phenotype in 92% of progeny following injection of unc-22 dsRNA into a control group of RNAi-competent (Bristol N2) animals, while only 2% of progeny from injection of rde-4(ne299) mutants showed the phenotype. This is consistent with the requirement for rde-4 in mediating a robust RNAi response,13 and with the persistence of residual RNAi in the mutants.12,17 Supply of a full-length rde-4 transgene to rde-4(ne299) animals restored the response to unc-22 dsRNA (87% of the resulting progeny twitched).

We then tested various truncated versions of RDE-4 (Fig. 1) for their ability to restore RNAi in the rde-4(ne299) null mutant. The N terminal domains were not absolutely required for RNAi activity, as the Δ(Nterm,dsRBD1) construct lacking both the N-terminus and the dsRBD1 domains rescued RNAi to the point where 48% of progeny twitched in levamisole. Individual ΔNterm and ΔdsRBD1 constructs also appeared to rescue, with the ΔNterm construct apparently rescuing somewhat weaker in the quantitative assays.

The ΔLinker and ΔdsRBD2 constructs failed to rescue the RNAi sensitivity of the rde-4(ne299) mutation in any of the assays. To confirm the ability of these deletions to produce a protein product, GFP tags were added to the N-terminus and the resulting derivatized versions confirmed to express by the appearance of GFP fluorescence (data not shown).

Assays with the ΔCterm (ΔC-Terminus) construct yielded partial, though variable rescue. Twitching above background levels was evident in all lines, but with considerable variability in incidence, suggesting a potential (albeit not absolute) requirement of the C terminus for robust RDE-4 function.

To test if the linker and dsRBD2 domains are sufficient for RDE-4 function in RNAi triggered by exogenous dsRNA, we engineered constructs that contained only the dsRBD2 domain (construct: +dsRBD2), or only the linker and the dsRBD2 domains (construct: +(Linker,dsRBD2)). No activity was observed with the +dsRBD2 construct, while significant rescue was observed with +(Linker,dsRBD2).

RDE-4 domain requirements in the response to transgene-encoded trigger RNA.

In addition to dsRNA injection, silencing can be triggered by the presence of sense-driving and/or antisense-driving segments of a target mRNA in the genome of an organism.32–34 Injection of unc-22 sense and antisense constructs (under control of the myo-3 promoter) has been shown to effectively silence the endogenous unc-22 gene in RNAi competent individuals and provides an assay for response to genome encoded trigger RNA.16 As noted in Table 2, some domain requirements for RDE-4 response to genome-encoded trigger RNA were similar to those for injected dsRNA. In particular, RDE-4 appeared to retain function in the absence of the N terminal and dsRBD1 segments, while no activity was observed in the absence of dsRBD2 or the linker. However, we also observed consistent quantitative and/or qualitative differences between the two RNAi trigger delivery methods, suggesting that the variation may be reflective of qualitative differences between assays, or of a biological trait of the RDE-4 protein. For instance, the ΔNterm construct rescued RNAi to a far greater extent in response to the transgene-encoded trigger than to injected dsRNA (Tables 1 and 2). On the other hand, we failed to observe RDE-4 function from the ΔCterm construct in these assays, likewise observing no activity with the +(Linker,dsRBD2) construct alone (Tables 1 and 2), suggesting the possibility of a more significant role for the C-terminal domain in responding to the genome-encoded trigger RNA population.

Table 2.

RNAi sensitivity of rde-4 worms rescued with full-length and truncated versions of rde-4 (trigger: transgene-encoded dsRNA)

| Name of construct | Domains retained in construct | Qualitative result | Quantitative results | |||||||

| N-term | dsRBD1 | Spacer | dsRBD2 | C-term | n | +Lev | −Lev | +Lev (Line) Twitchers: Non-Twitchers | −Lev (Line) Twitchers: Non-Twitchers | |

| pha-1* | − | − | − | − | − | 2 | (DI291a)- | (DI291a)- | (DI291c) 0:153 (DI291d) 0:799 |

|

| rde-4 full-length | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | (DI65a)++ | (DI65a)++ | (DI291e) 415:2 | |

| ΔNterm | − | + | + | + | + | 2 | (DI66a)++ | (DI66a)−+ | (DI285b) 65:15 (DI285c) 507:68 (DI285e) 192:9 |

|

| Δ(Nterm, dsRBD1) | − | − | + | + | + | 2 | ND | ND | (DI92a) 38:51 (DI290b) 12:756 (DI290c) 11:297 |

(DI92a) 10:74 |

| ΔdsRBD1 | + | − | + | + | + | 2 | (DI62a)+ | (DI62a)−+ | (DI286b) 231:140 (DI286c) 205:56 (DI286d) 239:158 |

|

| ΔSpacer | + | + | − | + | + | 2 | (DI63a)−+ | (DI63a)− | (DI287b) 0:162 (DI287i) 0:646 (DI287j) 0:634 |

|

| ΔdsRBD2 | + | + | + | − | + | 2 | (DI40b)− (DI40c)− |

(DI40b)− (DI40c)− |

(DI288b) 1:651 (DI288c) 1:446 (DI288d) 0:530 |

|

| ΔCterm^ | + | + | + | + | − | 2 | (DI91a)− | (DI91a)− | (DI289a) 0:811 (DI289c) 2:660 (DI289g) 0:624 |

|

| Δ(Nterm, Cterm) | − | + | + | + | − | 1 | (DI53a)+ (DI53b)+ |

(DI53a)−+ (DI53b)−+ |

ND | |

| +(dsRBD2) | − | − | − | + | − | 3 | (DI54a)− | (DI54a)− | ND | |

| +(Spacer, dsRBD2) | − | − | + | + | − | 1 | (DI55a)− | (DI55a)− | ND | |

rde-4(ne299)pha-1(e2123ts) mutant animals were transformed with a mixture containing one of various myo3::rde-4 constructs and pha-1(+). These worms were subsequently injected with two plasmids encoding for unc-22 sense and antisense RNA, expressed under control of the myo-3 promoter. Twitching behavior was assayed in the presence or absence of levamisole, and was classified as per criteria detailed in the legend for Table 1. n: Number of experiments. *Injected construct: rde-4(ne299); pha-1. ^Construct encodes for RDE-4 fused to an N-terminal GFP.

In addition to these differences between the two trigger delivery methods, we observed a degree of intrinsic variability in RNAi sensitivity between independent transgenic lines that carry the same rescuing construct with either RNAi trigger delivery method (Tables 1 and 2). This variability is likely to arise from a combination of non-uniformity in the expression of the rescuing rde-4 construct, and non-uniformity in the delivery of dsRNA that triggers RNAi in transgenic lines. For this reason, we examined several transgenic lines for each construct (Tables 1 and 2). While this provides independent measures for each assay, we stress that some variability between lines is unavoidable.

RDE-4 domains required for interactions with Dicer.

C. elegans has a single dicer homolog (DCR-1) that functions in diverse small RNA biogenesis pathways. Several independent studies have demonstrated that DCR-1 interacts with RDE-4.9,11,13,35 We tested the ability of DCR-1 to interact with our truncated versions of RDE-4, to study the relationship between interaction and RDE-4 activity (as previously assessed by restoration of RNAi proficiency). We employed a recently developed Differential CytoLocalization Assay (DCLA), wherein a membrane-tethered version of a protein (in this case, DCR-1) is used to determine re-localization of a GFP-fused interacting partner9 (here, various truncated versions of RDE-4). The presence and relative abundance of GFP-RDE-4, and interaction between membrane-tethered DCR-1 and GFP-RDE-4 was assessed in transgenic animals using a fluorescent compound microscope.

We found that ΔdsRBD2 and ΔLinker each failed to interact with DCR-1 in this assay (Table 3). Notably the resulting GFP fusions are expressed uniformly in the cytosol (data not shown), suggesting inability to join the now-tethered dicer-associated complex. Each of the remaining constructs tested displayed some degree of interaction with tethered DCR-1. This was particularly evident with the C terminal deletion (ΔCterm), and was weakest with the N terminal deletion (ΔNterm) (Table 3). The strong interaction of the ΔCterm construct, despite its mediocre activity in the RNAi rescue assay, suggests that dsRNA binding domains and DCR-1 interaction together may be insufficient for full RDE-4 activity in RNAi.

Table 3.

Interactions between RDE-4 truncations and Dicer-GFP by DCLA

| Name of construct | Domains retained in construct | # Lines | Interaction level | ||||

| N-term | dsRBD1 | Spacer | dsRBD2 | C-term | |||

| rde-4 full length | + | + | + | + | + | 2 | +++ |

| ΔNterm | − | + | + | + | + | 2 | −+ |

| ΔdsRBD1 | + | − | + | + | + | 2 | ++ |

| ΔSpacer | + | + | − | + | + | 2 | − |

| ΔdsRBD2 | + | + | + | − | + | 2 | − |

| ΔCterm | + | + | + | + | − | 2 | +++ |

RDE-4 domain requirements for interactions with the Dicer complex. rde-4 deletions were expressed as tethered derivatives on the cytosolic surfaces of intracellular membranes as described.9 The capacity of bound RDE-4 to re-localize Dicer was estimated by subsequent monitoring of the intracellular localization of a cytosolic Dicer-GFP fusion protein in two independent transgenic lines for each construct. Key for interpreting magnitude of interactions: [+++] Strong interaction. Complete or near-complete re-localization or Dicer-GFP to intracellular membranes. [++] Moderate interaction. Clear re-localization of some (but not all) Dicer-GFP to intracellular membranes. [+] Possible weak interaction. Slight strengthening of membrane Dicer-GFP signal above background levels. [− +] Borderline interaction. Very slight strengthening of membrane Dicer-GFP signal close to background levels. [−] No interaction detected. Dicer-GFP remains fully cytosolic.

RDE-4 mutants display defects in developmental and reproductive pathways at elevated temperatures.

dsRNA binding proteins (e.g., RDE-4), nucleases (such as DCR-1 and ERI-1) and RNA-directed RNA Polymerases (such as EGO-1 and RRF-3) cooperate in a complex network of RNA silencing pathways to produce tiers of small RNA effectors that regulate endogenous gene expression. Many of these central players in RNAi25–28 and indeed, even certain key small RNA effectors (reviewed in ref. 36), are required for viability and/or intact reproductive pathways, particularly at elevated temperatures.25,27,37,38 We chose to temperature-stress rde-4 mutants, to test whether lack of RDE-4 differentially impacts viability and reproductive capacity at low and elevated temperatures.

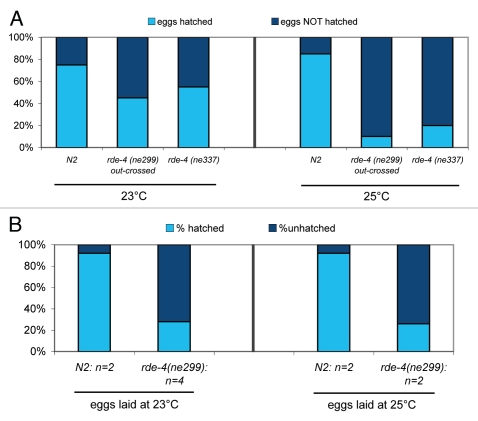

We observed lower hatch rates in rde-4(ne299) and rde-4(ne337) strains than in the Bristol N2 strain (Fig. 2A). All rde-4 mutants exhibited mild embryogenesis defects even at 23°C, and this was exacerbated at 25°C, suggesting reduced embryo viability at elevated temperatures. Moreover, this defect was evident both in embryos fertilized and reared at 25°C, and in embryos fertilized at 23°C and shifted up to 25°C (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Reduced hatching rates at elevated temperatures in rde-4 deficient worms. (A) N2, rde-4 (ne299; 6X outcrossed), and rde-4 (ne337) worms were allowed to lay eggs at 23°C or at 25°C for 30 hours. 20 eggs were picked, and number of hatched eggs at either temperature was inferred 48 hours later, by subtracting the larvae count from the initial egg count. (B) Reduced hatching rates are observed for rde-4 (ne299) worms compared to N2 worms, when fifty eggs laid at 23°C are shifted to 25°C, or when eggs laid at 25°C are maintained at 25°C. n represents number of experiments.

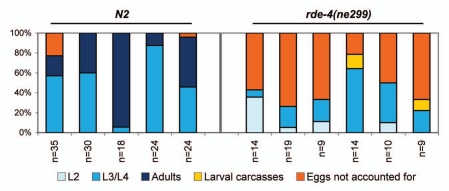

rde-4(ne299) animals also display delayed development at elevated temperatures. Five days post-egg lay at 25°C, no adult worms were visible in the rde-4(ne299) mutant populations (all viable progeny were in the L2–L4 larval stages), while 10–90% (n = 5) of progeny had progressed to the adult stage in the N2 animal populations (Fig. 3). In contrast, rde-4(ne299) and N2 animal populations displayed equivalent developmental profiles at 16°C (Sup. Fig. 1). For a more specific developmental profile, we followed the development of individual N2 and rde-4(ne299) L2s when shifted to 25°C (Fig. 4). This experiment provided us with the temporal resolution to determine whether the observed defect in larval development was a consequence of a delay in egg hatching or a delay in larval development. Indeed, as assessed by time to egg-bearing, rde-4(ne299) mutants appeared to lag by nearly a day compared to N2 animals (Fig. 4), suggesting that larval development is retarded in rde-4 mutants at elevated temperatures.

Figure 3.

rde-4 deficient worms demonstrate delayed embryonic/larval development at elevated temperatures. N2 and rde-4(ne299) adults reared at 25°C were allowed to lay eggs for 4 h at 25°C (day 1). Plates were maintained at 25°C, and animals were counted on day 3. Unaccounted eggs (inferred by initial egg count minus larvae count) and viable progeny were counted on day 5. The fraction of all animals at each stage on day 3 is shown. n represents the total number of animals counted.

Figure 4.

Temporal decrease in brood sizes at 25°C in rde-4 deficient worms, compared to N2. Four L2's from N2 and rde-4(ne299) worms reared at 20°C were transferred to individual plates and shifted to 25°C. The number of new F1 progeny per animal per day post-egg lay is shown as a stacked plot for two separate experiments (Exp1 and Exp2). The total number of F1 progeny per animal on any given day is the sum of new F1 progeny from that day and all days prior. Note the logarithmic scaling used for the Y-axis.

In addition to displaying developmental defects, temperature-shifted L2 populations appeared to produce fewer progeny up to day 4 post-temperature shift (Fig. 4), and continued to do so over an extended observation window of five to ten days (data not shown). We observed similar restriction of brood size when animals were temperature-shifted at the egg or L4 stages (data not shown). Thus, regardless of the stage at which the temperature shift occurred, rde-4 mutants possess a fraction of the egg-laying capacity of N2 animals, indicating that in addition to embryonic lethality, low egg numbers restrict population sizes in rde-4 mutants.

One concern in interpreting results from these experiments is that the observed temperature sensitive defects in rde-4 mutants may be a consequence of one or more secondary mutations that could have arisen in the strain before, during or after mutagenesis and outcrossing. Although we are not aware of any such mutations, it is important to consider their possible existence. Two observations make a second-hit model rather unlikely. First, we observed temperature-sensitive growth defects in an additional rde-4 mutant strain (rde-4(ne337)) strain. Second, the temperature sensitivity is shared between growth defects (this work) and RNAi defects12 that result from the rde-4(ne299) mutation. Despite these consistencies, it was conceivable that secondary mutations in both rde-4 strains might account for the observed high-temperature growth defects. To independently assay the genetic location of the temperature-sensitive growth character in rde-4(ne299), we carried out a set of mapping crosses using flanking markers dpy-18 and unc-32 that are separated by approximately eight map units. Segregation analysis showed that the RNAi deficiency and temperature-sensitive growth defects both mapped to this interval (data not shown). Furthermore, RNAi deficiency and temperature-sensitive growth defects co-segregated in nine out of nine identified crossovers in this interval (data not shown), narrowing the temperature-sensitive growth defect to a rather short segment including rde-4 and certainly consistent with a single mutation producing both phenotypes.

A non-autonomous role for RDE-4 in RNAi.

RNAi is known to involve cell-autonomous processes (wherein gene regulation is restricted spatially to the site of initial trigger delivery) and non-autonomous processes (wherein gene regulation spreads to tissues distal to the site of initial trigger delivery).39,40 We investigated the nature of autonomy in the requirement for RDE-4 in RNAi pathways that respond to foreign dsRNA. We note that determining the autonomy of RDE-4's roles in developmental pathways is complicated due to considerable challenges in transgene rescue of phenotypes associated with germline defects; thus we used somatic expression (in the body musculature) for these assays.

We assessed RNAi proficiency in rde-4(ne299) mutants rescued with functional copies of rde-4 provided by a transgene driving expression with the bodywall muscle-specific myo-3 promoter.45 A GFP reporter (myo-3::gfp) was included in each of the DNA mixes used for rescue, allowing definitive tracking of animals carrying the rescuing array. This strategy takes advantage of two features of injection-based transformation of C. elegans.41,42 First, transgenics obtained following DNA injection into the animal most often have the DNA assembled into extrachromosomal arrays that are relatively stable mitotically but lost at relatively high (and somewhat variable) frequencies during meiosis. Second, mixtures of DNA injected into C. elegans yield mixed extrachromosomal arrays with co-segregation of DNAs in the large (and mixed) extrachromosomal arrays that subsequently form. Transformed lines from injections of myo-3::rde and myo-3::gfp thus confer RDE and GFP expression, with the relevant expression lost in progeny that lose the arrays. To confirm loss of both markers in gfp-lacking animals we examined non-green animals and confirmed that they had also lost RNAi response activity (data not shown).

RDE-1 was used as a benchmark for autonomous function in the RNAi pathway.40 Two independent lines for rde-1 ex[myo3::rde-1; myo3::gfp] (herein referred to as rescued rde-1) and three independent lines for rde-4 ex[myo3::rde-1; myo3::gfp] (rescued rde-4) were generated and injected with unc-22 dsRNA (experimental outcomes are explained in Fig. 5A and B). All parent animals from the transgene rescued rde-4 and rde-1 backgrounds exhibited strong twitching when injected with the RNAi trigger (data not shown). However, their progeny exhibited marked differences in RNAi sensitivity. As would expected from the cell autonomy of RDE-1,43 progeny of rescued rde-1 animals displayed differential twitching, with twitching observed in progeny with functional RDE-1, and absent in progeny lacking RDE-1 (Fig. 5C). In contrast, both RDE4−/GFP− and RDE4+/GFP+ progeny from rescued rde-4 animals twitched (albeit, to varying degrees), with twitching exacerbated in the presence of levamisole (Fig. 5C). We note that animals that appear to have lost the transgenic array (i.e., are GFP−) fail to segregate any GFP+ animals in later generations (data not shown), and are resistant to RNAi, suggesting that the observed RNAi proficiency is not attributable merely to low levels of RDE-4 due to silencing and/or low transgene copy number, but rather points towards persistence of RNAi proficiency even in the event of true transgene loss. These data suggest that unlike RDE-1, RDE-4 functions in a non-autonomous manner to facilitate RNAi in the presence of a trigger.

Figure 5.

A non-autonomous role for the RDE-4 protein in RNAi. (A) Possible genotypes and associated phenotypes of progeny from a parent worm carrying the rde+; gfp+ extrachromosomal array. (B) Experimental setup and possible outcomes for distinguishing autonomous versus non-autonomous roles for RDE genes. dsRNA is injected into RDE-mutant worms (rde-1 or rde-4) that have been rescued with extra-chromosomal copies of the corresponding rde gene and gfp. GFP is used as a marker to track worms with wild-type RDE function. A non-autonomous role for the RDE gene product may be inferred if progeny remain RNAi-competent despite losing the extra-chromosomal array (i.e., are RDE-deficient and GFP-negative). (C) rde-1- and rde-4-deficient worms were injected with a mixture of myo3::rde-1 and myo3::gfp, and a mixture of myo3::rde-4 and myo3::gfp respectively. Independent transgenic lines (Lines 1–3) were established for each RDE background, and were injected with dsRNA against unc-22 (‘a’ and ‘b’ refer to separate experiments with the same line). Worms were stratified by RNAi sensitivity (as assayed by twitching capability), and by presence of rescuing RDE construct (as assayed by GFP expression). Number of progeny assayed in the rde-1 background: Line1a (23); Line1b (22); Line 2a (13); Line2b (41). Number of progeny assayed in the rde-4 background: Line1a (66); Line2a (11); Line3a (8).

Discussion

We have utilized a series of in vivo assays to establish the contribution of various domains of C. elegans RDE-4 to its role in RNA interference (RNAi). The minimal domain requirements for RDE-4's ability to bind DCR-1 extend this analysis and provide an initial functional map of RDE-4. Furthermore, we have classified the cellular need for RDE-4 in RNAi as non-autonomous, and have described a previously uncharacterized organismal requirement for RDE-4 in reproduction and development.

Domain requirements of RDE-4 for Dicer interaction and RNAi.

Data from our reconstitution assays indicate that the N terminal domains of RDE-4 comprising the N terminus and dsRBD1 may be non-essential for RNAi mediated by some trigger populations (Tables 1 and 2). Both domains can be removed without significantly affecting RDE-4's interaction with DCR-1, although removal of the N-terminus compromises this interaction to some extent. The sequence of dsRBD1 also appears to be less conserved than dsRBD2,13 further supporting the view that dsRBD1 may have lost the ability to bind dsRNA. These observations do not exclude the possibility that either the N terminus or dsRBD1 may interact with proteins other than DCR-1 either in the RDE-4/DCR-1 exogenous RNAi complex or in endogenous RNAi complexes.

Domains absolutely required for both DCR-1 interaction and RNAi reside in the linker and dsRBD2 domains (Tables 1 and 2). In fact, these two domains also appear to be sufficient for reconstituting RNAi (Table 1). Parker GS, et al. have proposed that RDE-4 might function as a dimer.11 Although our in vivo analysis does not directly bear on this question, the retention of function by RDE-4 constructs lacking the C terminal dimerization domain identified in vitro suggest that C terminus-mediated homodimerization and reconstitution of DCR-1 activity observed in vitro11 may not be essential to facilitate RNAi in vivo. Alternatively, the ΔCterm constructs may still undergo a low level of homodimerization and siRNA production that may not be detected within the sensitivity of the in vitro assays, but may be sufficient for borderline rescue of RNAi in our in vivo assays. Despite these observations, we do not rule out the possibility that the C terminus may be required for initiating alternative RNAi cascades such as endogenous RNAi, where C terminus-mediated homodimerization may facilitate endogenous siRNA formation.

Cell non-autonomous role for RDE-4 in RNAi.

Analysis of silencing under conditions where RDE-4 is provided maternally indicated a sufficiency of maternal expression in subsequent enforcement of RNA interference,15 which we have also confirmed (data not shown). Left open were the possibilities that (1) maternal expression provided sufficient protein for silencing in the next generation, or (2) there exists a diffusible signal generated in the presence of dsRNA and RDE-4 activity. We addressed the nature of the RDE-4 requirement by generating animals in which RDE-4 activity was absent in the germline and thus in the subsequent generation.

We demonstrated that RDE-4 functions in a cell non-autonomous manner to facilitate somatic RNAi in the rde-4-/- progeny of heterozygous animals exposed to an RNAi trigger (Fig. 5). Our results argue for the generation of a mobile signal in RNAi in a process that requires RDE-4 expression in an initial “generation” step, but which does not require RDE-4 expression in the target tissue in which gene silencing occurs. By contrast, RDE-1 appears to be required autonomously (i.e., in the target tissue) for a silencing response (Fig. 5 and reviewed in ref. 43). We do not know the nature of non-autonomy in RDE-4 function. Conceivably, this could involve export of RDE-4 protein by RDE-4(+) cells, or import of dsRNA and subsequent release of processed and/or protein-complexed derivatives that then promote systemic activity.

Role for RDE-4 in temperature-sensitive developmental and reproductive pathways.

rde-4 mutants display defects in embryonic development and fertility when temperature-stressed (Fig. 2–4). Mutations in several key players in the RNAi pathway, such as rrf-3, dcr-1 and ego-1 also cause defects ranging from embryonic/larval lethality to sterility.25–28 All these genes are also required for the biogenesis of small RNAs that target endogenous genes (endo-siRNAs) for downregulation.19,21,44 Additionally, the endo-siRNA pathway has been demonstrated to regulate developmental and fertility pathways.45 We postulate that the temperature-sensitive defects observed in rde-4 mutants may be a consequence of mRNA misregulation in the absence of a proficient endo-siRNA pathway in these mutants. Alternatively, RDE-4 may function in complexes distinct from RNAi (through binding partners that may be non-siRNA-like RNAs or proteins) that function to directly regulate development and fertility.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

Full-length and truncated versions (see Fig. 1 for descriptions of deletions) of rde-4 were driven by the myo-3 promoter in body muscle cells.46

Strains.

Hatching rates at elevated temperatures were determined using two strains generated by out-crossing the parental rde-4(ne299) strain13,16 6X (WM48), and one strain carrying the rde-4(ne337),13 allele out-crossed 1X (WM51). Temporal development, brood sizes and autonomy were assessed using one of the out-crossed rde-4(ne299) strains. Cell autonomy studies were performed in rde-4(ne299) and rde-1(ne300) (WM45),16 strains transformed with a mixture of myo3::rde-4 & myo3::gfp, and myo3::rde-1 & myo3::gfp, respectively. For assessing rescue of RNAi sensitivity with various rde-4 constructs, we first constructed a pha-1(e2123ts); rde-4(ne299) double mutant (PD5880), and co-injected the strain with constructs encoding for pha-1 and rde-4. Rescue of the temperature-sensitive phenotype of the pha-1(e2123ts) mutation with the pha-1 construct was used as a marker for successful transformation.47 Transgenic lines were passaged for several generations before they were assayed for RNA sensitivity. For the Differential CytoLocalization Assays (DCLA), constructs encoding for GFP-tagged DCR-1 and various N-terminal Membrane Tether Localization Signal (MTLS)-tagged versions of RDE-4 were co-injected into the N2 Bristol background, and animals expressing GFP were observed and documented as described in Blanchard et al.9 The C. elegans Bristol N2 strain, and/or the pha-1(e2123ts); rde-4(ne299) rescued with both the pha-1 and the full-length rde-4 constructs were used as RNAi proficient controls, as noted.

RNAi assays.

In experiments where RNAi sensitivity was assayed transiently, dsRNA corresponding to unc-22 was generated as described,48 and was injected at a concentration of ∼100 ng/µl into pha-1(e2123ts); rde-4(ne299) animals expressing myo-3::rde-4 and pha-1 constructs. In experiments where dsRNA was expressed from a transgene, myo-3-driven sense and antisense strands spanning a 0.5 Kb segment of unc-22,16 were co-injected with the pha-1 and myo3::rde-4 constructs into the pha-1(e2123ts); rde-4(ne299) background. In animals rescued for rde-4 function, both injected and transgene-generated unc-22 dsRNA trigger the RNAi-induced twitching phenotype. Animals were scored for twitching with and without the acetylcholine analogue levamisole,31 which enhances the twitching phenotype in animals with reduced or abrogated unc-22 function.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chaya Krishna, SiQun Xu, Karen Artiles, Rosa Alcazar, Jay Maniar, Julia Pak, Fred Tan, Hiroaki Tabara, Craig Mello, Rui Lu and Shou Wei Ding for their help and suggestions during the course of this work. This work was supported by grants R01GM37706 (to A.F.), T32GM07321 (D.B.) and T32-HG00044 (J.G.).

Abbreviations

- RDE-4

RNAi defective-4

- RRF-3

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase family-3

- EGO-1

enhancer of Glp-one

- ERI-1

enhancer of RNAi-1

- DCR

DICER

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- dsRBD

double-stranded RNA binding domain

- unc

uncoordinated

- endo

endogenous

- DCLA

differential cytolocalization assay

- MTLS

membrane tether localization signal

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Fischer SE. Small RNA-mediated gene silencing pathways in C. elegans. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 42:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Chang SS, Liu Y. RNA interference pathways in filamentous fungi. Cell Mol Life Sci. 67:3849–3863. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rij RP, Berezikov E. Small RNAs and the control of transposons and viruses in Drosophila. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazquez F, Legrand S, Windels D. The biosynthetic pathways and biological scopes of plant small RNAs. Trends Plant Sci. 15:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pederson T. Regulatory RNAs derived from transfer RNA? RNA. 2010;16:1865–1869. doi: 10.1261/rna.2266510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding SW. RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 10:632–644. doi: 10.1038/nri2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, Peter ME. MicroRNAs: key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:5959–5974. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard D, Hutter H, Fleenor J, Fire A. A differential cytolocalization assay for analysis of macromolecular assemblies in the eukaryotic cytoplasm. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2175–2184. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600025-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu R, Yigit E, Li WX, Ding SW. An RIG-I-Like RNA helicase mediates antiviral RNAi downstream of viral siRNA biogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:1000286. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker GS, Eckert DM, Bass BL. RDE-4 preferentially binds long dsRNA and its dimerization is necessary for cleavage of dsRNA to siRNA. RNA. 2006;12:807–818. doi: 10.1261/rna.2338706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrish S, Fire A. Distinct roles for RDE-1 and RDE-4 during RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA. 2001;7:1397–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabara H, Yigit E, Siomi H, Mello CC. The dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 interacts with RDE-1, DCR-1 and a DExH-box helicase to direct RNAi in C. elegans. Cell. 2002;109:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkins C, Dishongh R, Moore SC, Whitt MA, Chow M, Machaca K. RNA interference is an antiviral defence mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;436:1044–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature03957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grishok A, Tabara H, Mello CC. Genetic requirements for inheritance of RNAi in C. elegans. Science. 2000;287:2494–2497. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabara H, Sarkissian M, Kelly WG, Fleenor J, Grishok A, Timmons L, et al. The rde-1 gene, RNA interfer-ence and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell. 1999;99:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habig JW, Aruscavage PJ, Bass BL. In C. elegans, high levels of dsRNA allow RNAi in the absence of RDE-4. PLoS One. 2008;3:4052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tijsterman M, Ketting RF, Okihara KL, Sijen T, Plasterk RH. RNA helicase MUT-14-dependent gene silencing triggered in C. elegans by short antisense RNAs. Science. 2002;295:694–697. doi: 10.1126/science.1067534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gent JI, Lamm AT, Pavelec DM, Maniar JM, Parameswaran P, Tao L, et al. Distinct phases of siRNA synthesis in an endogenous RNAi pathway in C. elegans soma. Mol Cell. 2010;37:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee RC, Hammell CM, Ambros V. Interacting endogenous and exogenous RNAi pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA. 2006;12:589–597. doi: 10.1261/rna.2231506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasale JJ, Gu W, Thivierge C, Batista PJ, Claycomb JM, Youngman EM, et al. Sequential rounds of RNA-dependent RNA transcription drive endogenous small-RNA biogenesis in the ERGO-1/Argonaute pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3582–3587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911908107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grishok A, Sinskey JL, Sharp PA. Transcriptional silencing of a transgene by RNAi in the soma of C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2005;19:683–696. doi: 10.1101/gad.1247705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonkin LA, Bass BL. Mutations in RNAi rescue aberrant chemotaxis of ADAR mutants. Science. 2003;302:1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1091340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spike CA, Bader J, Reinke V, Strome S. DEPS-1 promotes P-granule assembly and RNA interference in C. elegans germ cells. Development. 2008;135:983–993. doi: 10.1242/dev.015552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gent JI, Schvarzstein M, Villeneuve AM, Gu SG, Jantsch V, Fire AZ, et al. A Caenorhabditis elegans RNA-directed RNA polymerase in sperm development and endogenous RNA interference. Genetics. 2009;183:1297–1314. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, et al. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmer F, Tijsterman M, Parrish S, Koushika SP, Nonet ML, Fire A, et al. Loss of the putative RNA-directed RNA polymerase RRF-3 makes C. elegans hypersensitive to RNAi. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smardon A, Spoerke JM, Stacey SC, Klein ME, Mackin N, Maine EM. EGO-1 is related to RNA-directed RNA polymerase and functions in germ-line development and RNA interference in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2000;10:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welker NC, Habig JW, Bass BL. Genes misregulated in C. elegans deficient in Dicer, RDE-4 or RDE-1 are enriched for innate immunity genes. RNA. 2007;13:1090–1102. doi: 10.1261/rna.542107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parrish S, Fleenor J, Xu S, Mello C, Fire A. Functional anatomy of a dsRNA trigger: differential requirement for the two trigger strands in RNA interference. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1077–1087. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R. Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell. 1990;2:279–289. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Krol AR, Mur LA, de Lange P, Mol JN, Stuitje AR. Inhibition of flower pigmentation by antisense CHS genes: promoter and minimal sequence requirements for the antisense effect. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:457–466. doi: 10.1007/BF00027492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fire A, Albertson D, Harrison SW, Moerman DG. Production of antisense RNA leads to effective and specific inhibition of gene expression in C. elegans muscle. Development. 1991;113:503–514. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duchaine TF, Wohlschlegel JA, Kennedy S, Bei Y, Conte D, Jr, Pang K, et al. Functional proteomics reveals the biochemical niche of C. elegans DCR-1 in multiple small-RNA-mediated pathways. Cell. 2006;124:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy S, Wang D, Ruvkun G. A conserved siRNA-degrading Nase negatively regulates RNA interference in C. elegans. Nature. 2004;427:645–649. doi: 10.1038/nature02302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maine EM, Hauth J, Ratliff T, Vought VE, She X, Kelly WG. EGO-1, a putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, is required for heterochromatin assembly on unpaired dna during C. elegans meiosis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1972–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2002;295:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1068836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han W, Sundaram P, Kenjale H, Grantham J, Timmons L. The Caenorhabditis elegans rsd-2 and rsd-6 genes are required for chromosome functions during exposure to unfavorable environments. Genetics. 2008;178:1875–1893. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stinchcomb DT, Shaw JE, Carr SH, Hirsh D. Extrachromosomal DNA transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3484–3496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qadota H, Inoue M, Hikita T, Koppen M, Hardin JD, Amano M, et al. Establishment of a tissue-specific RNAi system in C. elegans. Gene. 2007;400:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu W, Shirayama M, Conte D, Jr, Vasale J, Batista PJ, Claycomb JM, et al. Distinct argonaute-mediated 22G-RNA pathways direct genome surveillance in the C. elegans germline. Mol Cell. 2009;36:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han T, Manoharan AP, Harkins TT, Bouffard P, Fitzpatrick C, Chu DS, et al. 26G endo-siRNAs regulate spermatogenic and zygotic gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18674–18679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906378106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okkema PG, Harrison SW, Plunger V, Aryana A, Fire A. Sequence requirements for myosin gene expression and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;135:385–404. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Granato M, Schnabel H, Schnabel R. pha-1, a selectable marker for gene transfer in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1762–1763. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.9.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.