Abstract

Previous studies show that the MYCN and MDM2-p53 signal pathways are mutually regulated: MYCN stimulates MDM2 and p53 transcription, whereas MDM2 stabilizes MYCN mRNA and induces its translation. Herein, we report that the interaction between MDM2 and MYCN plays a critical role in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma tumor cell growth and survival. Distinct from the known role that MDM2 has in regulating tumor promotion in non-MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, in which MDM2 inhibits p53, we found that MDM2 stimulated tumor growth in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma in a p53-independent manner. In MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells, enforced expression of MDM2 further enhanced MYCN expression, yet no p53 inhibition was observed by MDM2 due to upregulation of MYCN that stimulated p53 transcription. Similarly, p53 expression remained unchanged in MDM2-silenced MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells because MDM2 inhibition resulted in a downregulation of MYCN that decreased p53 transcription, although the MDM2-mediated degradation of p53 was reduced. Also, we found that the enforced overexpression of MDM2, or conversely, the inhibition of overexpressed endogenous MDM2, led to either a remarkable increase or decrease in tumor growth, respectively, in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma (even though no p53 function was involved). These results suggest that p53 that is reciprocally regulated by MDM2 and MYCN is dispensable for suppression of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, and that the direct interaction between MDM2 and MYCN may contribute significantly to MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma growth and disease progression.

Key words: MYCN, Neuroblastoma, MDM2, p53, cell growth

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is a neural crest-derived tumor that arises from the postganglionic sympathetic tissue in either the adrenal gland or the paraspinal sympathetic chain. It is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children. This tumor type accounts for 15% of all childhood cancer deaths in the United States. The hallmark of neuroblastoma is the variability in clinical outcome: some tumors regress spontaneously; whereas others will progress relentlessly, despite the most intensive treatment.1,2

In neuroblastoma, unfavorable biologic characteristics include MYCN gene amplification, which occurs in about 25% of primary tumors.3–5 Although most neuroblastoma patients with this MYCN gene amplification have a worse prognosis, there are a few MYCN-amplified cases such as in stage 4s who experience a favorable outcome.6 In contrast, up to 50% of patients with high risk neuroblastoma lacking MYCN amplification will respond poorly to treatment and they will ultimately relapse and succumb to their disease.7 These discrepancies in outcome suggest that additional molecular mechanisms or signaling pathways besides MYCN amplification must contribute to rapid tumor progression and poor prognosis. For example, a recent study demonstrates that in relapsed neuroblastoma, there is a high frequency of p53/MDM2 pathway abnormalities.8 In particular, a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene promoter serves as a marker for an increased predisposition to develop tumors, as well as for neuroblastoma disease aggressiveness.9

The human MDM2 gene is another oncogene that is amplified in a variety of human cancers, including neuroblastoma.10 High levels of MDM2 expression can occur even in those neuroblastomas without MDM2 gene amplification: in some cases it is associated with a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene promoter.9 MDM2 gained considerable attention following its identification as the protein that negatively regulates the tumor suppressor p53. The N-terminus of the MDM2 protein binds to p53, restraining p53-mediated transcription;11 the C-terminus of MDM2 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, mediating the degradation of p53.12 MDM2 also plays p53-independent roles in oncogenesis. In addition to interacting with and regulating p53, it has been demonstrated that MDM2 interacts with other molecules, including specific proteins and RNA, which may contribute to its a p53-independent role in oncogenesis. For example, MDM2 was shown to bind to and ubiquitinateRb, resulting in Rb degradation and release of the E2F1 that promotes cell cycle progression.13 MDM2 also binds E2F1 directly, enhancing E2F1 stability.14 The C-terminal RING finger domain of MDM2 exhibits specific RNA binding ability.15 We recently reported that binding of the C-terminal RING domain of the MDM2 protein to the XIAP mRNA regulates translation of this apoptosis regulator, which is involved in the development of resistance to anticancer treatment.16

Interestingly, both MDM2 and p53 are regulated by MYCN. Like other members of the Myc family, MYCN is a transcriptional regulator. The specificity of MYCN transcription is mediated through binding to a core E-box promoter sequence, CAT/CGTG, found in the promoter region of target genes. MYCN has been shown to bind to the MDM2 promoter and to positively regulate its expression.17 MYCN is also able to bind to an E-box DNA binding motif within the p53 promoter, to induce its expression.18 Although no detailed studies have looked for the association between MYCN and MDM2 expression in neuroblastoma patient samples, it is known that MYCN amplification or high levels of MYCN expression are definitely associated with enhanced p53 expression in neuroblastoma patients.18 Furthermore, we have recently revealed that MDM2 is a translational activator of MYCN. MDM2, when translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, binds to the AU-rich elements of the MYCN 3′-UTR and regulates MYCN mRNA stabilization and its translation.19

Because MDM2 and MYCN are not only mutually regulated but also reciprocally regulate p53 in neuroblastoma, we are interested in investigating exactly how that cross talk between MYCN and the MDM2/p53 signaling pathway leads to individual expression of those molecules in neuroblastoma cells, and importantly, what is the impact of that cross talk on neuroblastoma cell growth and induction of apoptosis. In the present study, we selected neuroblastoma cell lines with or without MYCN gene amplification that either have or do not have MDM2 overexpression, and utilized gene transfection and gene knockdown by siRNA to carry out our investigation.

Results

Modulation of MDM2 differentially regulates p53 in neuroblastoma cells with and without MYCN amplification.

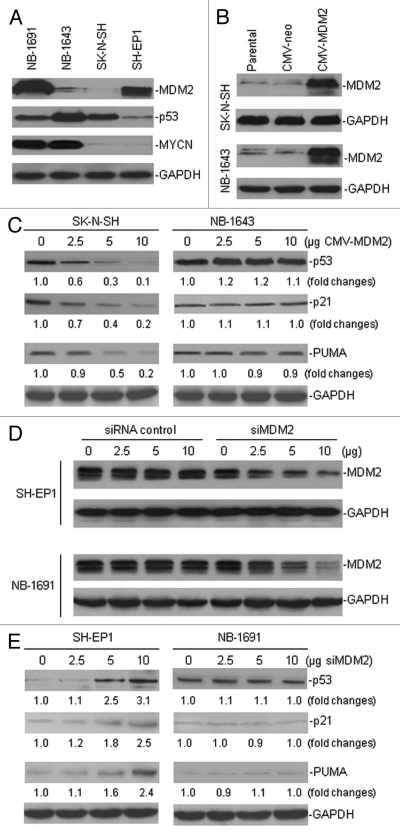

Previous studies demonstrated that MDM2 inhibits p53 and MYCN induces p53, while MDM2 and MYCN are mutually regulated. We studied how the expression and function of p53 is synthetically regulated by MDM2 and MYCN in neuroblastoma cells. We chose four neuroblastoma cell lines (NB-1691, NB-1643, SK-N-SH and SH-EP1), with or without MYCN amplification, that either have or do not have MDM2 overexpression (Fig. 1A). We performed MDM2 gene transfection in the non-MDM2-overexpressing cell lines SK-N-SH and NB-1643 (Fig. 1B). Enforced overexpression of MDM2 in the non-MYCN-amplified SK-N-SH cells resulted in inhibition of p53 expression. Thus, expression of both p53 transcription targets p21 and PUMA were also repressed in the MDM2-transfected SK-N-SH cells (Fig. 1C and left part). In contrast, overexpression of MDM2 in MYCN-amplified NB-1643 cells failed to alter the expression of p53 and its transcription targets p21 and PUMA (Fig. 1C and right part).

Figure 1.

The different effects of MDM2 on both the regulation of p53 expression and its function, in neuroblastoma cells with and without MYCN amplification. (A) Western blot assay for protein expression of MDM2, p53 and MYCN in four cultured neuroblastoma cell lines. (B) Enforced overexpression of MDM2 in SK-N-SH and NB-1691 cells by transfection of the expression plasmid CMV-MDM2, as detected by western blot analysis. (C) Expression of p53 and its down-stream target genes p21 and PUMA in MDM2-transfected cells, as detected by western blot assay. Labels under bands in the blot represent the protein levels after normalization to GAPDH, as compared with samples (0 was defined as 1 unit). (D) Inhibition of endogenous MDM2 by siRNA in SH-EP 1 and NB-1691 cells. Cells were transfected with different doses of the siMDM2 and siRNA control, as indicated. After a 24-h transfection, MDM2 expression was detected by western blot. (E) The expression of p53, p21 and PUMA in two MDM2-silenced cell lines with different MYCN expression, as detected by western blot assay.

In addition, we confirmed that the alteration of p53 expression and function after modulation of MDM2 occurs only in non-MYCN-amplified, but not in MYCN-amplified, neuroblastoma cell lines by inhibiting MDM2 in MDM2-overexpressing cells. We performed a knockdown of MDM2 in the NB-1691 and SH-EP1 cell lines by the transfection of the pSUPER/MDM2 plasmid into the cells, to produce siMDM2 (Fig. 1D). Silencing of MDM2 in the non-MYCN-amplified SH-EP1 cells resulted in an increased expression of p53, p21 and PUMA; whereas no induction of these proteins was observed in MYCN-amplified NB-1691 cells, following inhibition of endogenous MDM2 (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that the distinct regulation of p53 by MDM2 in different types of neuroblastoma cells is associated with the presence or absence of MYCN.

Interaction between MDM2 and MYCN synthetically regulates p53 in neuroblastoma cells.

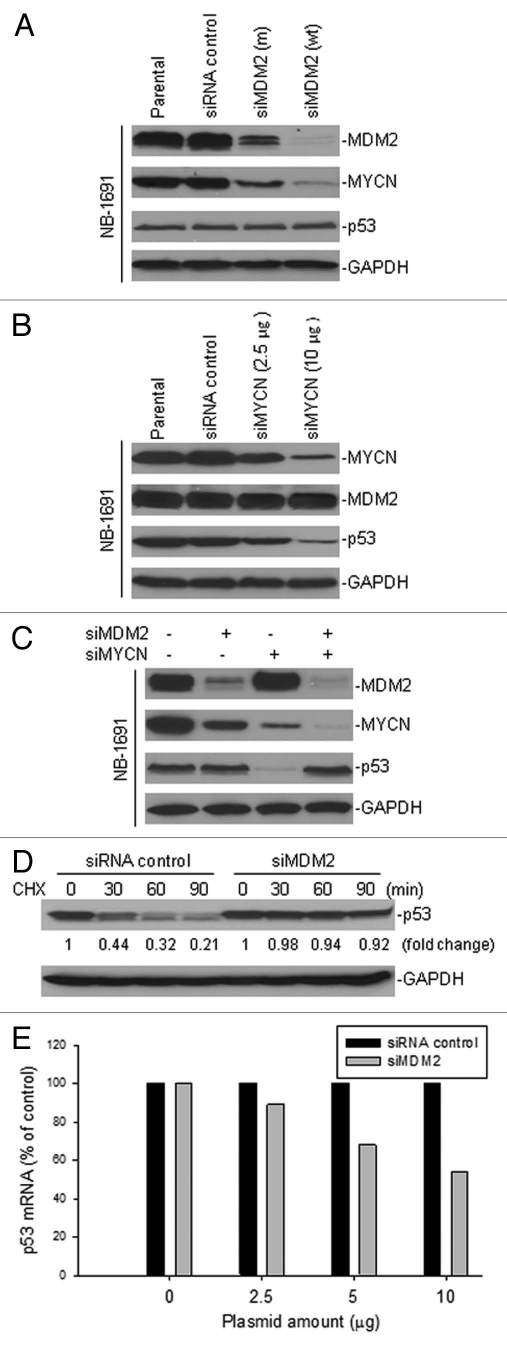

To investigate further the involvement of MYCN in the regulation of p53 by MDM2, we tested for the expression of MYCN and its association with p53 in MDM2-silenced cells. Consistent with our previously reported results in reference 19, the expression of MYCN in MDM2-overexpressing NB-1691 cells was downregulated by silencing of MDM2 with siRNA. As shown in Figure 2A, significant inhibition of MDM2 by transfection of wt siMDM2 was followed by a remarkable inhibition of MYCN, and even transfection of a mutant siMDM2 partially inhibited the expression levels of MDM2 and MYCN. We found that the expression of p53 remained unchanged in NB-1691 cells after transfection of either the wt or mutant siMDM2, when compared with both the parental NB-1691 and NB-1691 transfected with the control siRNA. We also tested the effects of silenced expression of MYCN on the expression of MDM2 and p53. In our cell model, the expression of p53, but not MDM2, was remarkably inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by silencing of MYCN in the MYCN-overexpressing NB-1691 cells (Fig. 2B). In addition, we performed a combination assay by simultaneously transfecting siMDM2 and siMYCN in NB-1691 cells to investigate their effects on p53 expression. Our results show that inhibition of MYCN, but not MDM2, significantly downregulated p53; yet inhibition of both MYCN and MDM2 did not change the expression of p53 (Fig. 2C). To evaluate whether the increased p53 by knockdown of MDM2 may be inhibited by the silencing of MYCN in NB-1691 cells, we performed a pulse-chase assay to measure the p53 protein turnover and RT-PCR to test p53 mRNA expression. Our results showed that silencing of MDM2 indeed stabilized p53 protein (Fig. 2D), while the p53 mRNA expression was downregulated in NB-1691 cells (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

The effect of inhibition of MDM2 and MYCN on the regulation of p53 in MYCN-amplified/MDM2-overexpressed neuroblastoma cells. (A) NB-1691 cells were transfected with either siMDM2 (wt), siMDM2 (m) or siRNA control, and the expression of MDM2, MYCN and p53 was detected by western blot assay. (B) NB-1691 cells were transfected with different amount of siMYCN and expression levels of MYCN, MDM2 and p53 were detected by western blot. (C) Expression of indicated proteins as detected by western blot, in NB-1691 cells that were transfected with siMDM2, in the presence or absence of co-transfection with siMYCN. (D) p53 protein turnover in NB-1691 cells transfected with siMDM2 and control siRNA. siRNA-transfected cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide (CHX). At selected times indicated after CHX, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blot assay. (E) p53 mRNA expression in NB-1691 transfected with siMDM2 and siRNA control was detected by quantitative RT-PCR.

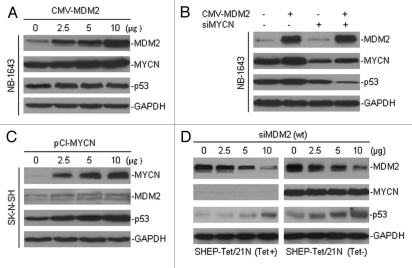

We also tested for the expression of MYCN and its association with p53 in MDM2-transfected cells. The results showed that the enforced overexpression of MDM2 further increased MYCN expression in NB-1643 cells, even though these cells already expressed a high level of MYCN, while the expression of p53 remained unchanged (Fig. 3A). Using a combination of MDM2 transfection and the silencing of MYCN by siRNA in NB-1643 cells, we found that the expression of p53 became significantly reduced by enforced overexpression of MDM2 in the presence of MYCN siRNA, as compared with cells that were only transfected with MYCN siRNA, without MDM2 overexpression (Fig. 3B). In addition, we tested the effects of enforced MYCN on the expression of MDM2 and p53. In our cell model, transfection of MYCN into the non-MYCN-amplified SK-N-SH cells slightly increased the expression of MDM2, but the expression of p53 was significantly upregulated by the transfected MYCN (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

The effect of MDM2 and MYCN modification on the regulation of p53 in neuroblastoma cells. (A) The MYCN-amplified NB-1643 cells were transfected with different amounts of MDM2 expression plasmid, as indicated. The expression levels of transfected MDM2, endogenous MYCN and p53 were tested by western blot assay. (B) Expression of MDM2, MYCN and p53 in NB-1643 cells transfected with MDM2, in the presence or absence of MYCN knockdown by transfection of siMYCN. (C) The SK-N-SH cells without MYCN amplification were transfected with a MYCN expression plasmid. Expression levels of the transfected MYCN, endogenous MDM2 and p53 were detected by western blot. (D) Effect of MDM2 inhibition by siRNA on regulation of p53 and ectopic MYCN in SHEP-Tet/21N cells in the presence and absence of tetracycline (Tet). Cells were cultured in medium with or without 1 µg/ml Tet and transfected with different amounts of siMDM2 for 24 h. The expression of proteins as indicated was detected by western blot.

Furthermore, to confirm that MDM2 and MYCN reciprocally regulate p53, we tested the effect of siMDM2 on p53 expression in SHEP-Tet/21N line with overexpression of MDM2 and with conditional expression of ectopic MYCN that was not regulated by MDM2 due to lack of original 3′UTR.19,20 We found that the expression of p53 was induced by siMDM2 in both SHEP-Tet/21N in the presence of tetracycline (without MYCN expression) and SHEP-Tet/21N in the absence of tetracycline (with MYCN expression), with higher levels of basic expression and induction of p53 in the latter than in the former (Fig. 3D). This suggests that inhibition of MDM2 and expression of ectopic MYCN additively induce p53 expression.

Taken together, these results indicate that MDM2 and MYCN reciprocally regulated p53, such that the expression and function of p53 remained unchanged in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma in response to MDM2 modification.

Differing cellular responses to silencing of MDM2 in MYCN-amplified and non-MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma.

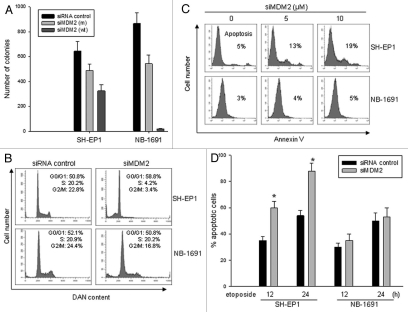

We evaluated the effect that MDM2 modulation, via inhibition by siRNA, has on cell growth, cell cycle progression and the induction of apoptosis in MDM2-overexpressing neuroblastoma cells either with or without MYCN amplification. We compared the colony formation abilities of both SH-EP1 (without MYCN amplification) and NB-1691 (with MYCN amplification) cell lines that were transfected with siMDM2 (wt), siMDM2 (m) and control siRNA. In proportion with the inhibition of MDM2 by siRNA, transfection of siMDM2 (wt) inhibited colony formation of SH-EP1 cells, while transfection of siMDM2 (m) partially inhibited colony formation, as compared with the control cells (Fig. 4A). As also is shown in Figure 4A, transfection of siMDM2 (wt) into the NB-1691 cells completely inhibited colony formation. Colonies were formed by NB-1691 cells transfected with siMDM2 (m), but the numbers of colonies formed were reduced when compared with cells transfected with the control siRNA.

Figure 4.

Different effects of MDM2 inhibition on the regulation of cell growth and apoptosis in MYCN-amplified and non-MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. (A) Clonogenic assay of SH-EP 1 and NB-1691 cells transfected with siMDM2 (wt), siMDM2 (m) and siRNA control. Cells (1 × 104) were seeded in soft agarose and cultured for 2–3 weeks. Colonies were counted under phase contrast microscopy. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments; bars ± SD (B) A cell cycle analysis in SH-EP 1 and NB-1691 cells, performed 24 h after transfection with siMDM2 and siRNA control. (C) Representative histograph of flow cytometry for detection of apoptosis in SH-EP 1 and NB-1691 cells after 24 h siMDM2 transfection with different amounts of plasmid, as indicated. Apoptotic cells were detected by annexin-V staining followed by flow cytometry. (D) The effects of MDM2 inhibition by siRNA on the sensitivity of SH-EP -1 and NB-1691 neuroblastoma cell lines to etoposide-induced apoptosis. The siMDM2 and siRNA control cells were treated with 10 µM etoposide for the indicated time, and then apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometry, *p < 0.01.

Because we found that inhibition of MDM2 resulted in distinct regulation of p53 in neuroblastoma cells with and without MYCN amplification (Fig. 1D and E), we tested for changes in cell cycle progression in the SH-EP1 and NB-1691 cells after siMDM2 transfection. As shown in Figure 4B, silencing of MDM2 in SH-EP1 cells led to an obvious G1 cell cycle arrest with G2/M depletion. In contrast, no G1 cell cycle arrest was observed in the NB-1691 cells that were transfected with MDM2 siRNA, although a mild G2 depletion occurred. These results implied that p53 functionality is possibly induced by inhibition of MDM2 in SH-EP1 cells, but not in NB-1691 cells. To further test for whether p53 is likely activated by knockdown of MDM2 in SH-EP1, but not in NB-1691, we examined apoptosis in these MDM2-silenced cells by annexin V staining and flow cytometry. Results showed that annexin V-positive cells were increased in the siMDM2-transfected SH-EP-1 cells, but not in siMDM2-transfected NB-1691 (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, we found that inhibition of MDM2 significantly sensitized SH-EP1 cells to etoposide-induced apoptosis. In contrast, the etoposide-induced apoptosis in NB-1691 was not obviously enhanced by silencing of MDM2 (Fig. 4D). Together with the results in Figure 1D and E, these data indicated that silencing of MDM2 in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma appears to inhibit cells growth in a p53-independent manner, whereas silencing of MDM2 in non-MYCN-amplified cells triggers p53-dependent apoptosis.

MDM2-induced MYCN expression is critical for cell growth in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma.

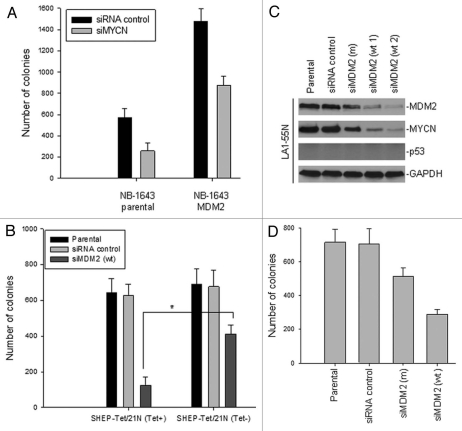

To further evaluate the role of MDM2-regulated MYCN in cell growth of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, we tested colony formation of MDM2-transfected cells in the presence or absence of siMYCN. As shown in Figure 5A, transfection of MDM2 in NB-1643 cells without siMYCN increased colony formation. Inhibition of MYCN with siMYCN significantly suppressed colony formation of NB-1643 cells transfected with MDM2. The growth of parental NB-1643 cells was also inhibited by siMYCN, suggesting that the amplified MYCN indeed plays a role in neuroblastoma growth. In addition, we tested the effect of siMDM2 on growth of SHEP-Tet/21N cells in the presence and absence of tetracycline. Clonogenic assay results showed that siMDM2-mediated inhibition of colony formation was significantly reduced in MYCN expressed SHEP-Tet/21N (Tet−) as compared in non-MYCN expressed SHEP-Tet/21N (Tet+) (Fig. 5B), although the levels of basic p53 expression and induction by siMDM2 in the former was even higher than in the latter. This suggests that the ectopic MYCN, which is not inhibited by siMDM2, reverse the siMDM2-mediated growth inhibition. Furthermore, we performed a knockdown of MDM2 in a p53-null/MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell line, LA1-55N, and found that MYCN expression was concomitantly downregulated by the inhibition of MDM2 (Fig. 5C). Inhibition of MDM2 and thus MYCN resulted in reduced colony formation by LA1-55N cells (Fig. 5D). These results further suggest that the regulation by MDM2 of MYCN was indeed p53-independent and likely plays a critical role in neuroblastoma cell growth and progression.

Figure 5.

Effects of MDM2 modulation on the cell growth of MYCN-overexpressed neuroblastoma. (A) Clonogenic assay of NB-1643 cells that were stably transfected with MDM2, as compared with parental cells in the presence (siMYCN) or absence (siRNA control) of MYCN siRNA. (B) Comparison of the effect of MDM2 inhibition on growth of cells with and without conditional MYCN expression. SHEP -Tet/21N cells in cultures with or without tetracycline (Tet) were similarly transfected with siMDM2 and control siRNA, and clonogenic assays were performed as in (A), *p < 0.01. (C) Stable suppression of MDM2 in p53-null LA1-55N cells by transfection of siMDM2. MDM2 and MYCN expression in parental LA1-55N cells and LA1-55N that were transfected with the siRNA control, siMDM2 (m), and siMDM2 (wt), as detected by western blot. (D) Clonogenic assay of LA1-55N cells transfected with siRNA control, siMDM2 (clone wt 2), and siMDM2 (m), or the untransfected parental cell line. Cell culture and colony counts were performed as in (A).

Discussion

We recently identified MYCN as a translational target of MDM2. When MDM2 is expressed in the cytoplasm, it can bind to the 3′-UTR of MYCN mRNA and this stabilizes the MYCN mRNA, resulting in enhanced MYCN protein synthesis.19 In the present study, we further investigated the impact of MDM2-regulated MYCN on critical functions such as cell growth and induction of apoptosis in neuroblastoma. Because MDM2 is a well-known inhibitor of the tumor suppressor p53, and both MDM2 and p53, in turn, are direct transcriptional targets of MYCN,17,18 we particularly wished to evaluate how the cross talk between MYCN and MDM2/p53 signaling might play a role in the regulation of neuroblastoma cell growth and apoptosis, to be able to eventually apply this knowledge to better eliminate or control this pediatric cancer. We focused our study on MDM2 modulation, either increasing it by gene transfection or decreasing it by a siRNA strategy, to test for the effect of MDM2 on the regulation of p53 and MYCN, and on the growth of neuroblastomas with or without MYCN gene amplification.

Herein, we demonstrated that in neuroblastoma cells without MYCN gene amplification, overexpression of MDM2 stimulates cell growth and survival, through inhibition of p53. In contrast, in neuroblastoma cells that have MYCN amplification, the oncogenic function of MDM2 with regard to cell growth and tumor progression is the induction of MYCN protein expression. Although the p53 gene is normal (or wild-type) in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, its expression and function is reciprocally regulated by both MDM2 and MYCN. MDM2 inhibits the tumor suppressor p53, whereas MYCN induces p53.

MYCN, like other members of the MYC family, plays a paradoxical role, as it regulates both cell proliferation20 and induction of apoptosis.21 Although the mechanism used by MYCN to regulate cell proliferation has not yet been completely defined, the MYCN-regulated induction of apoptosis is known to be associated with the activation of p53, because the p53 gene promoter contains a MYC E-Box response element and MYCN does induce p53 transcription.18 Furthermore, the MYCN-regulated p53 transcription is activated in neuroblastoma, as the study demonstrated a clear association between high p53 expression and increased MYCN expression and amplification. The mechanism by which MYCN induces p53-dependent apoptosis could partially explain why some MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cases are initially chemosensitive and why the expression of MYCN in non-MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas is not a predictor for outcome of treatment.22

Our studies showed that MDM2 plays a critical role in determining both cell growth and induction of apoptosis in neuroblastomas that are regulated by MYCN and p53. In agreement with a prior study by Chen et al.18 our results clearly showed that MYCN significantly induces p53 expression. In contrast, MYCN did not induce MDM2 expression in our neuroblastoma cell model, even though previous studies indicated that MDM2 is a transcriptional target of MYCN.17 Consistent with our own previous study,19 we found that in neuroblastoma, MYCN is induced by MDM2, no matter whether the cells express p53 or not. We discovered that in the absence of MDM2 expression, cell growth is slow and induction of cell death could occur by MYCN-induced p53-dependent apoptosis in neuroblastoma patients having high levels of MYCN expression or even amplification; thus, this subgroup of patients could have a favorable outcome. Yet in the presence of MDM2, the MYCN-induced p53 is abrogated, so the MDM2-induced MYCN plays a predominant role for cell proliferation. Therefore, those neuroblastoma patients with tumor cells expressing high levels of MDM2, no matter whether they originally had or did not have MYCN overexpression and amplification, could experience an unfavorable treatment outcome. This could explain why a number of neuroblastoma patients who are lacking MYCN amplification and overexpression still have a poor prognosis, and why overexpression of MDM2 may contribute to a worse outcome. Further detailed studies in a large group of neuroblastoma patients, to fully characterize the clinical association between a high level of MDM2 expression and treatment outcome, are definitely worthwhile. We note that a previous study has shown that a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene promoter, which results in enhanced MDM2 expression, can be a marker for increased predisposition to tumor development and disease aggressiveness in neuroblastoma.10

MDM2 has been well studied as an inhibitor of p53. Similar to studies in many other normal, wild-type p53 cancers, we found that inhibition of MDM2 expression resulted in activation of p53 and thus increased apoptosis in neuroblastomas having a normal p53, but without the presence of MYCN amplification or expression. However, we discovered that in neuroblastoma cells with both normal p53 and MYCN amplification, the silencing of MDM2 was not productive, as it led to no obvious induction of apoptosis. This lack of apoptosis induction was apparently associated with the absence of p53 activation. Although inhibition of MDM2 may be reducing p53 degradation, the downregulation of MYCN by MDM2 inhibition could be decreasing the production of the tumor suppressor p53. Thus, the total expression and function of p53 appeared to remain unchanged, so no p53-dependent induction of apoptosis occurs. However, we found that knockdown of MDM2 significantly suppressed the growth of the MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines, regardless of whether the cells had or did not have normal p53 expression. In accordance with this observation, the enforced overexpression of MDM2 increased MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma growth. These results suggested that MDM2-induced MYCN expression plays a critical role for tumor progression in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma and that this tumor-promoting role is p53-independent.

The reason why MYCN amplification or overexpression is associated with rapid cell growth and a more aggressive phenotype in neuroblastoma is still uncertain. The oncogenic property of MYCN that allows it to induce aberrant cell proliferation is most likely related to its transactivation activity. It is known that MYCN is a transcription factor that induces expression of MCM7,23 a mini-chromosome maintenance protein possessing the vital function of “licensing” DNA synthesis during the transition from G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle.24 Thus, MYCN-induced MCM7 expression may play a role in the observed cell proliferation and in tumor progression of neuroblastoma. A recent study also identified MYCN as an inducer of expression of Bmi1, the polycomb group protein that has been shown to directly induce cell proliferation and colony formation in neuroblastoma cells.25 Additionally, because MDM2 is a transcriptional target of MYCN and MYCN, in turn, is a translational target of MDM2, these MDM2-MYCN interactions may form a positive feedback loop allowing tumor promotion, specifically in MYCN-amplified/MDM2-overexpressed neuroblastomas. Because p53 is not involved in the tumor growth and progression regulated by the interaction between MDM2 and MYCN, it is reasonable to consider that targeting the interaction between MDM2 and MYCN, rather than targeting the interaction between MDM2 and p53, would likely be a novel concept for the development of a more effective anticancer treatment against MYCN-amplified refractory neuroblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines.

Six human neuroblastoma cell lines (NB-1691, NB-1643, SK-N-SH, SH-EP1, SHEP/Tet/21N and LA1-55N) were used in this study. Except for LA1-55N, which is p53 null, all the cell lines express wild-type p53. NB1691, NB-1643 and LA1-55N have MYCN amplification; while SH-EP1 and SK-N-SH express no MYCN amplification.19 The SHEP-Tet/21N expresses ectopic MYCN in the absence of tetracycline. All cell lines were obtained from Dr. H. Findley (Emory University), except for the SHEP-Tet/21N that was kindly provided by Dr. M. Schwab (dkfz, Germany). All cell lines were grown in standard culture medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 2 mmol/L of L-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 ug/ml streptomycin) at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Plasmids and gene transfection.

The MDM2 expression plasmid pCMV-MDM2 was provided by Dr. B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). The MYCN expression plasmid pCI-MYCN was a gift of Dr. NaoIkegaki (University of Illinois at Chicago). The pSUPER MDM2 siRNA plasmids were constructed by inserting a specific 19-nucleotide (nt) MDM2 sequence (GAA GTT ATT AAA GTC TGT T) into an expression plasmid, pSUPER-neo, purchased from OligoEngine (Seattle, WA), to generate the pSUPER/MDM2 plasmid. During the generation of pSUPER/MDM2 plasmid, a clone that contains the same 19-nt MDM2 sequence having a single nucleotide mutation at site 12 (A to C) was selected and served as control. A specific 19-nt MYCN sequence (AGA TGA CTT CTA CTT CGG C) was inserted into pSUPER-neo, to generate pSUPER/ MYCN siRNA plasmid. In addition, a 19 scrambled sequence (GAG GCT ATT ATA CTG TGA T) was also inserted into pSUPER to generate an additional control siRNA.

To enforce MDM2 and MYCN expression in those cells with naturally low levels of expression of these proteins, the pCMV-MDM2, pCI-MYCN and control plasmids were either stably or transiently transfected into cells by electroporation at 300 V, 950 µF, using a Gene Pulser II System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For the stable gene transfection, the cells were seeded 48 h posttransfection into culture dishes for the selection of G418-resistant colonies, then growing them in medium containing G-418 (300 µg/ml) for 2–3 weeks. The resulting clones were picked and grown in RPMI medium with or without G-418. For stable or transient transfection of siMDM2 and siMYCN plasmids, the cells with high levels of MDM2 expression and/or MYCN amplification in an exponential growth stage were transfected with pSUPER/MDM2 (wt), pSUPER/MDM2 (m) and pSUPER/MYCN plasmids, either alone or in combination, using the electroporation method described above.

Western blot analyses.

Whole cell protein samples were prepared by lysing cells for 30 min at 4°C in a lysis buffer composed of 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Nonidet p-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 20 µg/ml aprotinin and 25 µg/ml leupeptin. Equal amounts of the protein extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose filter. After blocking with buffer containing 5% non-fat milk, 20 mM TRISHCl (pH 7.5), and 500 mM NaCl for 1 h at room temperature; the filter was incubated with specific antibody probes against the proteins of interest for 1 h at room temperature; washed; incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody; and then developed using a chemiluminescent detection system (ECL, Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, England). After stripping, the same filters were re-probed with an anti-GAPDH antibody, to control for equal protein loading and protein integrity.

Pulse-chase assay.

The p53 protein turnover was tested for by a standard protein-synthesis-inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) assay. Briefly, cells were treated with 50 µg/ml CHX for different times before lysis in the presence or absence of transfection with either siMDM2 or siRNA control, and then p53 expression was detected by western blot analysis.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

The total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to examine the expression of p53 mRNA in MDM2-silenced NB-1691 cells. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with a mixture of random nonamers and oligo-dT as primers (Qiagen). Amplification of p53 was performed with a 7500 Real-Time RT-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using a QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers for p53 and the house-keeper gene GAPDH were purchased from Qiagen.

Clonogenic assay.

The soft agarose method was used to measure colony formation. Briefly, a bottom layer of a low-melting-point agarose solution, containing 0.5% agarose in a final concentration of 1x RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, was poured into gridded 35 mm dishes and allowed to gel. A top layer was added, containing the prepared cells (trypsinized, gene or siRNA-transfected, counted), 0.35% agarose, and 1x medium as the diluent. These cells in soft agarose were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 2 to 3 weeks, at which point they were fixed with formalin. The colonies that were formed were scored using phase microscopy (cutoff value: 50 viable cells).

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was performed to analyze the cell cycle position and quantity of apoptosis. For cell cycle analysis, 5 × 105 cells were collected, rinsed twice with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol for 1 h at 4°C. Next, they were washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 30 µl of phosphate citrate buffer (0.1 M Na citrate/0.2 M Na2HPO4) for 30 min, at room temperature. After re-washing with PBS, they were suspended in 0.5 ml PBS containing 20 µg/ml of propidium iodide (PI) and 20 µg/ml of RNase A and incubated at 4°C for at least 0.5 h. Samples were analyzed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) and WinList software (Verity Software House, Inc.). To quantitate apoptotic cells by annexin-V staining, cells with or without gene transfection and treatment were washed once with PBS, and then stained with FITC-annexin V and PI, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Stained cells were analyzed by FACScan.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA123490, R01 CA143107 to M.Z.) and CURE (M.Z. and L.G.).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

References

- 1.Bowen KA, Chung DH. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:350–356. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832b1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller S, Matthay KK. Neuroblastoma: biology and staging. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11:431–438. doi: 10.1007/s11912-009-0059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maris JM, Matthay KK. Molecular biology of neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2264–2279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE, Bishop JM. Amplification of N-myc in untreated human neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science. 1984;224:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.6719137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeger RC, Brodeur GM, Sather H, Dalton A, Siegel SE, Wong KY, et al. Association of multiple copies of the N-myc oncogene with rapid progression of neuroblastomas. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1111–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510313131802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonini GP, Boni L, Pession A, Rogers D, Iolascon A, Basso G, et al. MYCN oncogene amplification in neuroblastoma is associated with worse prognosis, except in stage 4s: the Italian experience with 295 children. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:85–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, Stram DO, Harris RE, Ramsay NK, et al. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation and 13-Cis-retinoic acid. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr-Wilkinson J, O'Toole K, Wood KM, Challen CC, Baker AG, Board JR, et al. High frequency of p53/MDM2/p14ARF pathway abnormalities in relapsed neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1108–1118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattelani S, Defferrari R, Marsilio S, Bussolari R, Candini O, Corradini F, et al. Impact of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene on neuroblastoma development and aggressiveness: results of a pilot study on 239 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3248–3253. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corvi R, Savelyeva L, Breit S, Wenzel A, Handgretinger R, Barak J, et al. Non-syntenic amplification of MDM2 and MYCN in human neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 1995;10:1081–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson D, George D, Levine AJ. The MDM-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. MDM2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao ZX, Chen J, Levine AJ, Modjtahedi N, Xing J, Sellers WR, et al. Interaction between the retinoblastoma protein and the oncoprotein MDM2. Nature. 1995;375:694–698. doi: 10.1038/375694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Wang H, Li M, Rayburn ER, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Stabilization of E2F1 protein by MDM2 through the E2F1 ubiquitination pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24:7238–7247. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elenbaas B, Dobbelstein M, Roth J, Shenk T, Levine AJ. The MDM2 oncoprotein binds specifically to RNA through its RING finger domain. Mol Med. 1996;2:439–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu L, Zhu N, Zhang H, Durden DL, Feng Y, Zhou M. Regulation of XIAP translation and induction by MDM2 following irradiation. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slack A, Chen Z, Tonelli R, Pule M, Hunt L, Pession A, et al. The p53 regulatory gene MDM2 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. ProcNatlAcadSci USA. 2005;102:731–736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405495102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Iraci N, Gherardi S, Gamble LD, Wood KM, Perini G, et al. p53 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1377–1388. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu L, Zhang H, He J, Li J, Zhou M. MDM2 regulates MYCN mRNA stabilization and translation in human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.343. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutz W, Stöhr M, Schürmann J, Wenzel A, Löhr A, Schwab M. Conditional expression of N-myc in human neuroblastoma cells increases expression of alpha-prothymosin and ornithine decarboxylase and accelerates progression into S-phase early after mitogenic stimulation of quiescent cells. Oncogene. 1996;13:803–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulda S, Lutz W, Schwab M, Debatin KM. MycN sensitizes neuroblastoma cells for drug-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:1479–1486. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn SL, London WB, Huang D, Katzenstein HM, Salwen HR, Reinhart T, et al. MYCN expression is not prognostic of adverse outcome in advanced-stage neuroblastoma with nonamplified MYCN. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3604–3613. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.21.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shohet JM, Hicks MJ, Plon SE, Burlingame SM, Stuart S, Chen SY, et al. Minichromosome maintenance protein MCM7 is a direct target of the MYCN transcription factor in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1123–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takisawa H, Mimura S, Kubota Y. Eukaryotic DNA replication: from pre-replication complex to initiation complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:690–696. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochiai H, Takenobu H, Nakagawa A, Yamaguchi Y, Kimura M, Ohira M, et al. Bmi1 is a MYCN target gene that regulates tumorigenesis through repression of KIF1Bbeta and TSLC1 in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:2681–2690. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]