Abstract

In spite of improvements in global health over the 20th century, health inequities are increasing. Mounting evidence suggests that reducing health inequities requires taking action on the social determinants of health (SDOH), which include income, education, employment, political empowerment and other factors. This paper introduces an alternative health education curriculum, developed by the US-based non-profit organization Just Health Action, which teaches critical health literacy as a step towards empowering people to achieve health equity. Critical health literacy is defined as an individual's understanding of the SDOH combined with the skills to take action at both the individual and the community level. Prior to describing our curricular framework, we connect the recommendations of the World Health Organization Commission on the SDOH with the objectives of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion by arguing that achieving them is reliant on critical health literacy. Then we describe our four-part curricular framework for teaching critical health literacy. Part 1, Knowledge, focuses on teaching the SDOH and the paradigm of health as a human right. Part 2, Compass, refers to activities that help students find their own direction as a social change agent. Part 3, Skills, refers to teaching specific advocacy tools and strategies. Part 4, Action, refers to the development and implementation of an action intended to increase health equity by addressing the SDOH. We describe activities that we use to motivate, engage and empower students to take action on the SDOH and provide examples of advocacy skills students have learned and actions they have implemented.

Keywords: social determinants of health, health equity, advocacy, health education

INTRODUCTION

Although global health has improved steadily over the 20th century, health inequities both between and within countries are increasing (Murray et al., 2006; Berkman, 2009). Health outcomes fall along a social gradient; at every step on the socioeconomic ladder, poorer people have poorer health (Wilkinson, 2005; Marmot et al., 2008). Many health inequities start as early as the womb and continue to increase throughout adulthood (Case et al., 2002; Lu and Halfon, 2003; Cheng and Jenkins, 2009). The August, 2008 release of the final report of the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) has led to a heightened sense of urgency to address health inequities. Health inequities refer to systematic gaps in health outcomes between different groups of people that are judged to be avoidable and therefore are considered unfair and unjust (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). (In this paper, we adopt the nomenclature of the WHO Commission on the SDOH by using the terms ‘health inequities’ and ‘health equity’. For helpful discussion of the conceptual issues surrounding the terms ‘health inequities’, ‘health inequalities’ and ‘health disparities’, see Carter-Pokras and Baquet, 2002; Braveman, 2006.)

The Commission outlined the evidence to propose that the unacceptable inequities in health can be substantially reduced by taking action on the SDOH (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). Social determinants include, but are not limited to, income, early life experiences, education, food security, employment, health care services, social cohesion, political empowerment and gender equity. These determinants are sometimes referred to as the ‘causes of the causes’ because they are an ‘upstream’ source of ‘downstream’ individual behaviors and biological traits (Marmot, 2005). The Commission details three calls for action: (1) improve daily living conditions; (2) tackle inequitable distribution of power and resources; and (3) measure and understand the problem. Action 3 specifies the need to raise awareness of the SDOH through training and education (including the development of SDOH curricula) among medical and health professionals, as well as the general public. In Action 3, the Commission specifically states that ‘the understanding of the SDOH among the general public needs to be improved as a new part of health literacy … The scope of health literacy should be expanded to include the ability to access, understand, evaluate, and communicate information on the social determinants of health’ (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008: 189). A similar call to action to improve health literacy as a way to reduce health inequities and alleviate social injustices has also been made on the national level in the USA (Freedman et al., 2009).

Just Health Action (JHA) is a non-profit organization based in Seattle, Washington, USA, that has developed a unique curriculum to teach critical health literacy as a means to take action on the SDOH to achieve health equity. This paper outlines JHA's critical health literacy model. First, we connect the goals of the WHO Commission on the SDOH and the goals of WHO health promotion experts by arguing that they are both reliant on achieving critical health literacy. Then we present our critical health literacy pedagogical framework, providing examples of activities and actions our course participants have conducted. We conclude with a brief discussion of our evaluation process.

CRITICAL HEALTH LITERACY: THE NEXUS BETWEEN SDOH COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS AND HEALTH PROMOTION OUTCOMES

Health literacy is a concept with important theoretical roots in the health promotion literature. The WHO defines health literacy as ‘the personal, cognitive and social skills which determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health’ (Nutbeam, 2000: 263). Health education is considered the most obvious tool for increasing health literacy. However, prior to the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, drafted by the WHO in 1986 (World Health Organization, 1986), many health education theories focused on individual level risk factors and behavior change, such as the health belief model (Becker, 1974) or the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Since population health inequities are rooted in structural and social determinants, education that focuses exclusively on individual level risk factors is unlikely to eliminate inequities across social or economic groups because it fails to address their upstream causes. This limitation was understood by the framers of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, who defined health promotion as actions and education that sought to modify not only individual behaviors, but also address the public policies and socioeconomic conditions that have an indirect impact on health (Nutbeam, 2000).

Health literacy, then, should not only encompass health education regarding individual lifestyles, it should incorporate the empowerment of individuals and communities to take action on social, economic and political determinants. Nutbeam's three-level definition of health literacy succinctly addresses this point. Level 1, functional health literacy, refers to the communication of factual information regarding health risks. Level 2, interactive health literacy, involves the development of personal skills such as problem solving, communication and decision-making so that an individual can act independently on the knowledge received. Level 3, critical health literacy, refers to an individual's understanding of the SDOH combined with the skills to take action at both the individual and community level (Nutbeam, 2000). [In addition to Nutbeam, numerous authors have defined or operationalized health literacy in ecological terms (Kickbusch, 2001; Levin-Zamir and Peterburg, 2001; Ratzan, 2001; St Leger, 2001; Wang, 2001). Kickbusch recently emphasized the importance of considering population levels of health literacy as a means to bring health promotion into political debate (Kickbusch, 2009). Freedman et al. suggest that the concept of ‘public health literacy’ be incorporated into health literacy frameworks (Freedman et al., 2009). We utilize Nutbeam's definition of health literacy because it concisely highlights the necessity for education and action at both the individual and population level.]

The authors of the Ottawa Charter identify three primary ‘modifiable’ health promotion outcomes: (1) health literacy, (2) healthy public policy and (3) community action for health (Nutbeam, 1998). [These health promotion outcomes are defined in the WHO ‘Health promotion glossary’ (Nutbeam, 1998).] Using Nutbeam's three-level conceptualization of health literacy, we argue that Level 3, critical health literacy, is a necessary precondition for developing and implementing healthy public policy as well as for taking community action for health. Why? Because individuals and communities that both understand the SDOH and have skills to take action on them are more likely to advocate at the community and policy levels. Empowerment is an important step in this process; ‘ … an empowered community is one in which individuals and organizations apply their skills and resources in collective efforts to address health priorities and meet their respective health needs’ (Nutbeam, 1998: 354). Furthermore, since the SDOH Commission's recommended actions to improve daily living conditions (Action 1) and tackle the inequitable distribution of power and resources (Action 2) are political goals, we argue that they, too, are dependent on achieving a critically health literate citizenry. Health literacy is an educational tool that can be used to ‘inform, enlighten and empower individuals and communities so that they are aware of the political nature of health equity’ (Sparks, 2009: 201).

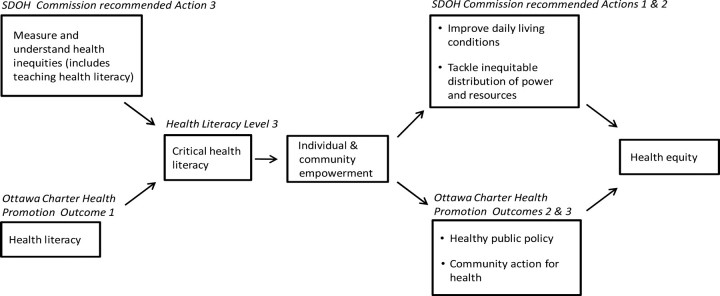

Figure 1 shows the relationship we draw between the Ottawa Charter health promotion outcomes and the recommendations of the Commission on the SDOH, linked by critical health literacy. We conceive of critical health literacy as a key step in the process of empowering individuals and communities to generate societal changes needed to achieve greater health equity. Our educational framework therefore focuses on teaching critical health literacy.

Fig. 1:

Nexus between SDOH Commission recommendations and Ottawa Charter health promotion outcomes to achieve health equity.

JHA CRITICAL HEALTH LITERACY FRAMEWORK

Just Health Action (JHA) has been working since 2004 to develop and teach a critical health literacy curriculum. We have taught in diverse educational settings throughout the Pacific Northwest, USA, including in graduate and undergraduate university courses (global health, public health, world population issues, environmental health and urban planning), secondary school settings, at community health centers, and at an afterschool program for low income, Latina youth. The executive director of JHA works as a consultant, collaborating with schools, universities, government agencies and non-profit organizations. Two JHA advisory board members are faculty at universities, and a third advisory board member has developed and taught JHA curriculum in various secondary school settings. The length of our SDOH programs has ranged from one 2-h class, where we introduced the SDOH and established the foundation for future educational collaboration, to a 12-week, 100-h course, which included both classroom and experiential field activities. Specific SDOH topics we have covered include obesity, housing, environmental justice, racism, income inequality, globalization and others.

Our pedagogy is interactive and encourages critical analysis and reflection, similar to education for ‘critical consciousness’ advocated by Freire (Freire, 1970). Past health researchers have applied Freire's empowerment philosophy to health education as a means to increase health literacy (Rudd and Comings, 1994) and to conduct community action (Wallerstein and Bernstein, 1988; Wallerstein, 1992; Wallerstein and Sanchez-Merki, 1994; Minkler, 2004). JHA's approach links these empowerment concepts with critical health literacy. We hypothesize that if we teach students to understand the SDOH and teach them skills to take action on these root causes, their increased empowerment to act will lead to improved health equity.

We conceptualize our critical health literacy framework in four parts. Part 1, Knowledge, focuses on teaching the SDOH and the paradigm of health as a human right. Part 2, Compass, refers to activities that help students find their own direction as a social change agent. Part 3, Skills, refers to teaching specific advocacy tools and strategies. Part 4, Action, refers to the development and implementation of an action intended to increase health equity by addressing the SDOH.

Although we always teach content from each of the four parts of our critical health literacy framework, the particular knowledge topics and the number of compass and action skills we teach vary from group to group, as do the students' final actions. Factors that determine the content are the learners' age and skill level, the learning objectives identified by the group, and the length of time of our course or workshop. Our curriculum is intentionally adaptable and we add new content and action skills as we work with new audiences and within different contexts. The next sections describe each component in greater detail.

Knowledge

Knowledge of the SDOH is the foundation from which individuals become critically health literate. The knowledge segment of our curriculum introduces students to SDOH research and literature on health as a human right. With regard to SDOH research, we begin with three topics: ‘what is health’; ‘health inequities’ and ‘causes-of-the-causes’. In ‘what is health’, students conduct a health mapping/diagramming activity in which they draw the factors they consider to be fundamental to their health. The resulting health diagrams invariably lead students to the realization that health is not merely health care and the determinants of health are broader than individual behaviors. We then analyze theoretical models of the SDOH (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991; Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; Thomas and Prentice, 2008) and introduce metrics to measure health at the population level, such as mortality rates and other indices (homicide rates, teen births etc.). By the end of this segment, students clearly differentiate between ‘individual health medicine’ (such as exercise, eat well and take your blood pressure medication) and ‘population health medicine’ (such as pass ‘no smoking’ legislation or organize a rally for universal health care).

We then introduce students to the topic of health inequities. Through readings and discussion, we explore students' personal values and beliefs concerning equality vs. equity; examine the scientific evidence of health inequities on a local, regional, national or global level; and discuss the effects of a particular inequity (such as obesity) on different population groups. We introduce students to a list of questions they might consider when analyzing any health outcome, including whether one group of people is disproportionately affected by the problem. The exercises teach students to identify population level health outcomes and realize that health problems are distributed in socially, economically and politically patterned ways.

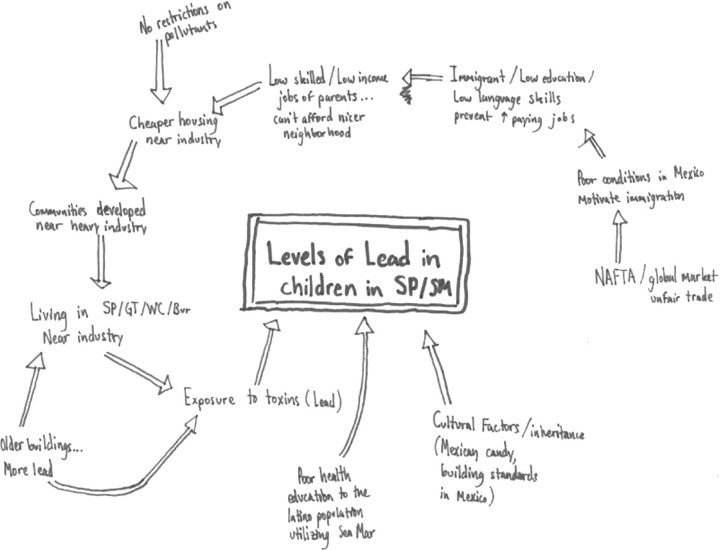

Next, we teach students to identify the upstream causes of a health problem by conducting a ‘causes-of-the-causes’ analysis, in which health determinants are positioned based on their level of influence on a particular health issue. Using smoking as an example, ‘causes-of-the-causes’ enables a student to understand that the reasons an individual might initiate smoking are not simply a result of downstream factors such as individual will power, but also a result of upstream factors such as poverty; lack of education; peer, societal and media pressures—i.e. factors that often lie beyond individual control.

Figure 2 provides a sample ‘causes-of-the-causes’ analysis, drawn by a HealthCorps volunteer [HealthCorps (www.communityhealthcorps.org) is a community-based volunteer program that promotes health care for underserved populations while training a future health care workforce.] serving at Sea Mar Community Health Centers (www.seamar.org), which specializes in providing health and human services to Latinos. The student analyzed levels of lead in children. Starting from the proximate cause of exposure to toxins from living near industrial sites, he ultimately linked childhood lead exposure to the global market and international trade agreements. Examples of additional problems that our students have diagrammed include homelessness, malaria, child malnutrition, depression, hate crimes and others.

Fig. 2:

Sample causes-of-the-causes analysis using lead poisoning as health outcome, drawn by HealthCorps volunteer Martin Escandon in 2008. Note: ‘SP/SM’ and ‘SP/GT/WC/Bur’ refer to specific neighborhoods in Seattle.

Depending on the timeframe we have for a course or workshop, we then discuss the paradigm of health as a human right (World Health Organization, 2007; Backman et al., 2008; Pillay, 2008; Chapman, 2009; Fox and Meier, 2009). We begin by asking students to conduct a personal reflection in which they name three human rights they consider to be the most valuable to them and then recall (and share if they feel comfortable) whether they have experienced any of their rights being violated. This process personalizes the potentially abstract notion of human rights and sets the stage for a rich discussion. Then we give each student a copy of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations, 1948). Analyzing all 30 articles, first we ask them to find their three most valued personal rights among the articles (it usually comes as a surprise to students that everyone's rights can be found in the comprehensive document), and second, to notate every reference to health or the SDOH that they can find throughout the articles. We form a list of all the articles that they believe relate to health. Oftentimes, students find that they can link every article to health, since they are now considering social and structural determinants. For example, the right to healthy work conditions, education, freedom from discrimination and adequate clothing and housing relate to the SDOH (Chapman, 2009). After analyzing the UDHR, we discuss additional United Nations human rights instruments and have students map the links between health and human rights. Readings include the Declaration of Alma Ata and a discussion of the history of the movement for ‘health for all’ (Werner and Sanders, 1997; Lawn et al., 2008). [To date, we have taught our human rights module in undergraduate university classes and to HealthCorps volunteers. Although we have yet to teach this portion of the curriculum to audiences with low literacy, we believe that it is adaptable to any group. The fact that we begin the human rights lesson with a discussion of personal rights and rights violations brings the topic directly into participants' experiences. Indeed, this exercise might particularly resonate with low literacy audiences, who are likely to have been disproportionately affected by inequities. A low literacy audience could work through the UDHR articles using pictures, story-telling or other non-text-based activities. We have been inspired by works such as ‘Helping Health Workers Learn’ (Werner and Bower, 1982) and the use of photo-novels (Rudd and Comings, 1994), and plan to have future students (at all literacy levels) design picture-based materials on human rights issues.]

Nearly all governments have health-related rights enshrined in their constitutions or have signed at least one United Nations document highlighting the right to health (Birn, 2009; Chapman, 2009). Thus, the human rights approach converts addressing the SDOH from being a purely ethical imperative into a legal imperative. ‘Reinforced by law, human rights are equity and ethics with teeth’ (Hunt, 2009: 38). Through analysis of human rights documents, students are familiarized with legally binding, internationally recognized instruments that can be used for policy advocacy by holding governments and agencies accountable to measure, monitor and set standards for healthy outcomes.

Additional examples of didactic techniques that we have used to teach SDOH concepts are described in the other literature (Bezruchka, 2009) and additional examples of student work can be viewed on the JHA website (www.justhealthaction.org). Once students learn the evidence, their interest is fueled.

Compass

Rooted in knowledge of the SDOH, our students then conduct a variety of activities to find their individual sense of direction as change agents. The goal of this section is to motivate students to advocate for health equity in a manner that suits their individual lifestyle and skill set. The ‘compass’ activities are divided into four parts: ‘unpacking advocacy’; ‘find your passion’; ‘vision and goals’ and ‘fuel your fire’.

Since people engage in civic society in different ways, we begin ‘unpacking advocacy’ by introducing JHA's ‘advocacy continuum’, which is adapted from Bickford and Reynolds (Bickford and Reynolds, 2002). The following example uses homelessness to illustrate JHA's ‘advocacy continuum’ (Gould et al., 2010). At one end of the continuum, a person can advocate for change through an individual act. For example, someone may donate money or time to a homeless shelter. In the middle of the continuum, an individual can advocate for change through community service, for example, by serving food in a shelter. On the other end of the continuum is activism, defined as acts intended to address the upstream, structural causes of a social problem. For homelessness, someone might advocate for fair housing policies, improved access to mental health services or alleviation of poverty. An activist response to homelessness critically questions why homelessness exists in one's community and develops strategies that can be taken to reduce or eliminate the problem on a structural level. While it is natural that individuals will advocate at different positions along this continuum, JHA's critical health literacy model is designed to teach students to take action at the activist level.

After discussing advocacy, students draw a personal ‘advocacy life map’ which assists them in articulating the ‘find your passion’ and ‘vision and goals’ portions of the ‘compass’. Studying their own drawing, they identify themes and consider what health-related issues they are passionate about. Next, they create an advocacy work plan in which they articulate a vision, goals and write an advocacy mission statement. Then they develop an action proposal for their JHA class/workshop project. When time allows, we guide students through a personal SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) [The personal SWOT analysis is adapted from MindTools: http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTMC_05_1.htm.] analysis for their advocacy.

The final segment of the compass portion, ‘fuel your fire’, consists of activities that aid students in the development of strategies to stay inspired and motivated in their advocacy efforts. The goal is to combat the cult of powerlessness, or the sense that the world's problems are so enormous that individual efforts are futile. Students interview their heroes and translate their stories into advice. At the end of the compass section, students have learned several techniques they can refer to as they hone their personal value system, their advocacy plans and consider how to maintain inspiration.

Skills

The skills portion of the curriculum focuses on diverse skills and strategies that students can use to take action on the SDOH. We have developed three course standards: an action letter workshop on persuasive writing; an introduction to the ORID facilitation technique; and dissemination. In the action letter workshop, we teach students journalistic techniques for persuasive writing. They then write an action letter, which is a position statement reflecting the writer's evidence-based position on a health issue, that is mailed to a key decision-maker or a newspaper. The activity gives students the opportunity to express their opinion in a purposeful and active way. We also teach students to lead health equity discussions on various SDOH topics using the ORID (Objective, Reflective, Interpretative and Decisional) facilitation technique. ORID represents different types of questions that are used to guide a group in a participatory conversation that identifies problems and brainstorms solutions. [We adapted ORID from the Institute for Cultural Affairs, (http://www.ica-usa.org/index.php). Further information about ORID and sample facilitation questions can be found at www.justhealthaction.org.] Finally, we teach different methods to disseminate knowledge, such as curriculum development and teaching, street theater and art activism. These tools require students to develop their research, analysis and presentation skills, as they produce content to disseminate in a creative, interactive manner.

Some courses culminate in a community-action project. In these cases, we teach students skills to work with community groups to conduct a project that is activist in nature. First, students conduct a ‘SDOH street-walk’ to map local population health issues. Then they communicate with community members to clarify needs and identify collaborating partners. We teach students a consensus-based facilitation method (also adapted from the Institute for Cultural Affairs) that they use to come to consensus on a specific SDOH action project. Finally, students conduct the action, which involves working with community members to implement the project in a culturally competent manner and to ensure its sustainability when students have moved on. There are also instances in which our students are themselves members of the community where the action is conducted. This is an ideal situation for building community empowerment.

Because we do not want lack of skills to be the obstacle to taking action, JHA is prepared to work with students to identify and/or learn whatever skills they need to complete their project, so skills are continually being added to the advocacy toolkit. When we lack the expertise to teach a particular skill, we collaborate with an expert who can co-teach or provide advice.

Action

The final step in our curriculum is for students to develop and implement a SDOH action. Because the timeframe we have to teach our curriculum varies greatly, the scope of the action project also varies. Table 1 displays example actions that our students have conducted, linked with the advocacy skill utilized.

Table 1:

Example advocacy skills linked to specific actions taken by our students

| Advocacy skill | Example actions by our students/workshop participants |

|---|---|

| Action letter | Letters to policy leaders, organizations, newspapers etc. regarding a health issue |

| Facilitation | 1. Teaching ORID technique using unnatural causes documentary series (www.unnaturalcauses.org) |

| 2. Lead workshop on advocacy writing | |

| Research, analysis and presentation | 1. Research and presentations on health inequity issues |

| 2. Presentations on global and local action projects | |

| 3. Researching comparative health system policies | |

| 4. Using human rights framework as evaluation instrument to assess current health policies | |

| 5. Interviewing local policy leaders about their knowledge of and attitudes towards health oriented public policy | |

| Curriculum design and teaching (dissemination) | 1. Health system policies in other countries compared to US |

| 2. Teach SDOH curriculum in secondary schools | |

| 3. How racism is embodied | |

| Art activism (dissemination) | Posters about SDOH subjects (income inequality, HIV/AIDS, gender inequality etc.) |

| Street theater (dissemination) | Performances at regional transit centers about teenage pregnancy and youth violence |

| Community project | 1. Helping a low income, minority community start a farmer's market |

| 2. As part of an obesity campaign, raising money for a community center to buy scholarships for low income, minority youth to join sports teams | |

| 3. Graffiti cover-up and litter cleanup campaign and advice to youth about relationship between graffiti and gangs |

CURRICULUM EVALUATION

JHA uses both process and outcome evaluations in most of its teaching venues. Our process evaluation has played an essential role in the development of the critical health literacy framework presented here. By necessity, we revise and augment our curriculum with each new group according to their particular objectives and skill levels. For example, in a series of modules we lead at a secondary school where we have been working since 2004, we collaborate with the instructors to plan the curriculum, send them the lesson plans in advance for input and engage in post-lesson debriefs to change the upcoming sessions based on student reactions and journal reflections (Gould et al., 2010).

In another example, we have an annual agreement with the Sea Mar Community Health Centers Health Corps volunteer program (described above) to teach a five-part population health workshop series with each new cohort of volunteers. We work closely with the program manager to revise the curriculum after each workshop and at the end of each annual series, often resulting in the development of new curriculum. For instance, one cohort of volunteers consistently questioned how they can operationalize the SDOH in the medical care settings where they work. Consequently, we are developing new curriculum where volunteers work with clinicians and other health professionals to integrate the SDOH into the medical care paradigm. One of the results has been to design a SDOH-oriented patient intake questionnaire in collaboration with a Sea Mar clinic obstetrician. We hope to develop SDOH intake questionnaires for multiple clinical settings (i.e. physical therapists, alternative care etc.).

Finally, we also conduct an outcome evaluation that measures individual level critical health literacy. Although there are many tools to measure health literacy, to our knowledge, there is no well-established tool specifically to measure critical health literacy (Nutbeam, 2008). [Fortunately, as we write, there is a multinational effort underway to measure health literacy across Europe. The European Health Literacy Survey (www.health-literacy.eu) is the first international health literacy survey and will result in data sets for in-depth analysis of health literacy concepts.] Hence, we have developed a pre- and post-test evaluation survey that we use at most of our teaching venues. Operationalizing Nutbeam's definition of critical health literacy—an individual's understanding of the SDOH combined with the skills to take action at both the individual and community level (Nutbeam, 2000)—we measure individuals' change along four dimensions: (1) knowledge of the SDOH, health inequities and health as a human right; 2) attitudes regarding SDOH, human rights and activism; (3) feelings of empowerment to use new skills to take action on the SDOH (includes measuring new skills acquired) and (4) future intentions to take action on the SDOH. An increase in post-test levels along these four dimensions indicates that the curriculum, consisting of knowledge, compass, skills and action segments, has resulted in increased individual level critical health literacy. Our preliminary evaluation results have been positive, and we plan to publish detailed results of the implementation and evaluation of our curriculum in future papers.

Critical health literacy may be operationalized and measured at various levels of analysis: individual, organizational and community. So far, our evaluations have focused on individual level changes in critical health literacy. We are currently developing measures to assess organizational level critical health literacy as well. A long-term goal is to collect longitudinal data from individuals, organizations and communities we work with to assess their engagement in health advocacy and to explore whether and how the curriculum may have contributed to actions that result in greater health equity. Such actions include the SDOH Commission recommendations and health promotion goals modeled in Figure 1, such as enacting healthy public policy and improving daily living conditions. Another measurable element of our critical health literacy educational process, also modeled in Figure 1, is increased empowerment to act on the SDOH, which can be operationalized and measured at the individual, community and organizational levels.

CONCLUSION

At a time of increasing health inequities both between and within countries, achieving health equity is a pressing concern. Both the Commission on the SDOH and the authors of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion recognize this goal and recommend health literacy as necessary step in the process. Using Nutbeam's three-level definition of health literacy, we believe that successfully teaching Level 3, critical health literacy, will produce empowered health advocates who can effectively engage in individual and community actions to reduce health inequities. This JHA critical health literacy framework has been designed to educate individuals and communities about the SDOH, help them become inspired advocates and teach the requisite skills to take action on upstream determinants.

FUNDING

Funding received for developing and teaching this critical health literacy curriculum comes from contracts received by Just Health Action including Sea Mar Community Health Centers, Seattle, Washington; Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition, Seattle, Washington; Puget Sound Early College, Highline, Washington; Poverty Race & Research Action Institute, Washington DC. Honoraria are received from multiple teaching venues around Washington State but most often from University of Washington, Seattle, Washington and Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Backman G., Hunt P., Khosla R., Jaramillo-Strouss C., Fikre B., Rumble D., et al. Health systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet. 2008;372:2047–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61781-X. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61781-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. H. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–473. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F. Social epidemiology: social determinants of health in the United States: are we losing ground? Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:27–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100310. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezruchka S. Promoting public understanding of population health. In: Babones S. J., editor. Social Inequality and Public Health. Bristol, UK: Bristol Policy Press; 2009. pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bickford D., Reynolds N. Activism and service-learning: reframing volunteerism as acts of dissent. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture. 2002;2:229–252. doi:10.1215/15314200-2-2-229. [Google Scholar]

- Birn A. Making it politic(al): closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Social Medicine. 2009;4:166–182. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annual Review Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras O., Baquet C. What is a ‘health disparity’? Public Health Reports. 2002;117:426–434. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.5.426. doi:10.1093/phr/117.5.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A., Lubotsky D., Paxon C. Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient. American Economic Review. 2002;92:1308–1334. doi: 10.1257/000282802762024520. doi:10.1257/000282802762024520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. Globalization, human rights, and the social determinants of health. Bioethics. 2009;23:97–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00716.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T., Jenkins R. Health disparities across the lifespan: where are the children? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2491–2492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.848. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on social determinants of health. www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html. (last accessed 23 December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren G., Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm: Institute of Futures Studies; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fox A., Meier B. Health as freedom: addressing social determinants of global health inequities through the human right to development. Bioethics. 2009;23:112–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00718.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D. A., Bess K. D., Tucker H. A., Boyd D. L., Tuckman A. M., Wallston K. A. Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36:446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum/Seabody; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gould L., Mogford L., DeVoght A. Challenges and successes of teaching the social determinants of health to adolescents: case examples in Seattle, Washington. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11(Suppl. 1):26S–33S. doi: 10.1177/1524839909360172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P. Missed opportunities: human rights and the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Global Health Promotion. 2009;16:36–41. doi: 10.1177/1757975909103747. doi:10.1177/1757975909103747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. Health literacy: addressing the health and education divide. Health Promotion International. 2001;16:289–297. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.3.289. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. Health literacy: engaging in a political debate. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54:131–132. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-7073-1. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-7073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn J., Rohde J., Rifkin S., Were M., Paul V., Chopra M. Alma-Ata 30 years on: revolutionary, relevant, and time to revitalize. Lancet. 2008;372:917–927. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61402-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin-Zamir D., Peterburg Y. Health literacy in health systems: perspectives on patient self-management in Israel. Health Promotion International. 2001;16:87–94. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.1.87. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. C., Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a lifecourse perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2003;7:13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. doi:10.1023/A:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M., Friel S., Bell R., Houweling T. A. J., Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2nd edition. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. J. L., Kulkarni S. C., Michaud C., Tomijima N., Bulzacchelli M. T., Iandiorio T. J., et al. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3:1513–1524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promotion International. 1998;13:349–364. doi:10.1093/heapro/13.4.349. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15:259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay N. Right to health and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Lancet. 2008;372:2005–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61783-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan S. Health literacy: communication for the public good. Health Promotion International. 2001;16:207–214. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.2.207. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd R., Comings J. Learner developed materials: an empowering product. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21:313–327. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks M. Acting on the social determinants of health: health promotion needs to get more political. Health Promotion International. 2009;24:199–202. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap027. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Leger L. Schools, health literacy and public health: possibilities and challenges. Health Promotion International. 2001;16:197–205. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.2.197. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N., Prentice B. Exploring the intersection of public health and social justice: the bay area regional health inequities initiative. NACCHO Exchange. 2008;7:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1992;6:197–205. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Sanchez-Merki V. Freirian praxis in health education: research results from an adolescent prevention program. Health Education Research. 1994;9:105–118. doi: 10.1093/her/9.1.105. doi:10.1093/her/9.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. Critical health literacy: a case study from China in schistosomiasis control. Health Promotion International. 2001;15:269–274. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.269. [Google Scholar]

- Werner D., Bower B. Helping Health Workers Learn. Palo Alto, CA: The Hesperian Foundation; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Werner D., Sanders D. Questioning the Solution: The Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival. Humanities Press International, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. G. The Impact of Inequality: How to make Sick Societies Healthier. New York: New Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf. (last accessed 23 December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO/OHCHR/323; 2007. The right to health joint fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs323_en.pdf. (last accessed 23 December 2009). [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948 http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/ (last accessed 23 December 2009) [Google Scholar]