Abstract

The development of multiple agents with potent antiretroviral activity against HIV has ushered in a new age of optimism in the management of patients infected with the virus. However, the viruses’ dynamic ability to develop resistance against these agents necessitates the investigation of novel targets for viral suppression. Raltegravir represents a first-in-class agent targeting the HIV integrase enzyme, which is responsible for integration of virally encoded DNA into the host genome. Over the last 5 years, clinical trials data has demonstrated an increasing role for raltegravir in the management of both treatment-experienced and treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected patients. This review focuses on the evidence supporting raltegravir’s efficacy in an array of clinical settings. Other HIV-1 integrase inhibitors in development are also briefly discussed.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy, raltegravir

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 33 million people are currently living with HIV worldwide.1 Fortunately 30 years into the epidemic, an entire arsenal of medications is available to combat the replication of the virus in resource-rich parts of the world. Most of these antiretrovirals have targeted inhibition of two enzymes critical for viral replication: protease and reverse transcriptase. More recently developed drugs are capable of inhibiting viral fusion with host cells (enfurvitide) and viral entry via the chemokine co-receptor-5 (CCR-5) site (maraviroc) on CD4+ cells. Raltegravir (Isentress®, Merck) represents a first-in-class antiretroviral that targets the integrase enzyme, which is primarily responsible for integrating virally encoded DNA into the host genome.2 In the 4 years since the approval of raltegravir by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it has assumed an increasing role in the treatment of antiretroviral-naïve patients, while remaining a cornerstone of salvage regimens in treatment-experienced patients.

HIV integration

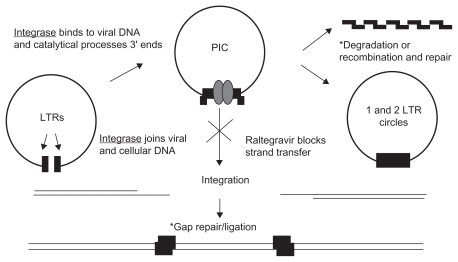

The integration of HIV-1-derived DNA into the host genome is a two-step process separated chronologically and geographically, mediated by the HIV-1 integrase (IN) enzyme. After the transcription of the viral DNA by reverse transcriptase in the cytoplasm, the integrase enzyme binds the DNA in a specific region of long-term repeats. The first step of integration involves the cleavage of 2 nucleotides at the 3′ end of the viral DNA leaving suitable 3′-OH ends for integration of the DNA into the host genome. The IN enzyme remains bound to the DNA after cleavage and, along with a number of other bound viral proteins, forms the preintegration complex (PIC). The PIC then migrates into the host nucleus for the second part of integration, strand transfer. Finally, host DNA is cleaved by the IN enzyme, and the 3′-OH ends are ligated to the host DNA3–8 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of HIV integration and the mechanism of raltegravir.

Note: *Cellular functions.

Abbreviations: LTRs, long-term repeats; PIC, preintegration complex.

Integrase inhibitors all appear to block integration via a similar mechanism. The target is the catalytic binding site of divalent cations to the IN enzyme in the catalytic core domain (CCD). Specifically, integrase inhibitors chelate Mg2+ from the DDE motif in the CCD rendering the enzyme unable to complete strand transfer.9 Although reports of compounds that inhibit HIV-1 integrase date back almost 20 years, the major breakthrough in the development of clinically effective integrase inhibitors was the identification of diketo acid derivatives as selective inhibitors of the strand transfer reaction mediated by the IN enzyme in 2000.6 A seminal report by Hazuda et al demonstrated that these compounds were able to inhibit HIV-1 without affecting reverse transcriptase activity, solely by inhibition of strand transfer by the IN enzyme.10 Diketo acid moieties have the ability to chelate magnesium from the active site of the IN enzyme thus rendering the metal-dependent phosphotransferase responsible for strand transfer inactive.9,11 Continued research revealed that the naphthyridine carboxamide derivatives are also capable of activity against HIV integrase indistinguishable from the diketo acids. A compound with a naphthyridine carboxamides moiety was the first to suppress simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) successfully in rhesus macacques via the virus’ integrase.12 Raltegravir (MK-0518), is a direct result of the optimization of compounds related to the naphthyridine carboxamide family.13

Pharmacology and drug interactions

Raltegravir has potent activity against HIV-1 with a 95% inhibitory concentration (IC95) of 31 nmol/L in human T lymphoid cell cultures incubated in 50% human serum. It also has activity against HIV-2 in vitro.2 Raltegravir’s antiviral activity is synergistic when incubated with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in vitro. Usual dosage for raltegravir is 400 mg twice daily with or without food.2 Single dose studies in HIV-uninfected persons revealed a biphasic peak in drug concentrations, with an initial peak at 1 hour. The terminal half-life was approximately 9 hours with steady state usually achieved after approximately 2 days. Raltegravir is absorbed quite rapidly with a median time to maximum concentration (Tmax) of approximately 3 hours, although this is highly variable among individuals. The drug is eliminated mostly by hepatic metabolism via the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltranferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) pathway. UGT1A1 converts raltegravir to its primary metabolite through the process of glucuronidation. Oral bioavailability is approximately 30%.14

Food intake has no clinically significant impact on raltegravir’s absorption. Age or gender does not appear to play a role in the drug’s pharmacokinetics either.2 Data on pharmacokinetics for extremely underweight (BMI < 18) or overweight (BMI > 37) individuals are not available. Findings from a single dose study evaluating the effect of moderate hepatic insufficiency on raltegravir metabolism showed that although the C12h was higher in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment (C12h ratio 1.26, 90% CI 0.41–1.77), the difference did not reach statistical significance.15 There was also no significant difference in the mean area under the curve (AUC) between the two groups of subjects. Only 9% of raltegravir is excreted unchanged through the urine. Accordingly, there was no statistically significant difference between the AUC, Cmax, or C12h of subjects with severe renal impairment (GFR < 30 mL/min) and those with normal renal function.15 Minimal clearance of raltegravir by hemodialysis is suggested in a few case reports.16,17 Raltegravir appears to be well distributed in the body, reaching concentrations that exceed the IC95 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), seminal and cervicovaginal fluid.14,18

Raltegravir has a low propensity for drug–drug interactions. In vitro studies with human hepatocyte cultures have shown that it does not inhibit or induce any of the major cytochrome P450 enzymes. It is a substrate, but not an inhibitor of p-glycoprotein. Raltegravir has no significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of methadone, lamotrigine, midazolam, or proton pump inhibitors.14,19 An important exception to this favorable drug interaction profile of raltegravir is rifampin, an important antituberculosis drug and a potent inducer of UGT1A1. Multiple studies have shown that rifampin significantly decreases the C12h, AUC, and Cmax of raltegravir in vivo. Thus, the FDA recommended dose of raltegravir when used with rifampin is 800 mg twice daily.2 However, rifabutin is the preferred rifamycin for the treatment of tuberculosis in patients taking raltegravir.20

Raltegravir and other antiretrovirals do not affect the pharmacokinetics of one another in most instances (Table 1). However, 3 studies show that raltegravir plasma levels are significantly increased when it is administered with atazanavir. The aggregate C12h, AUC, and Cmax ratios (raltegravir + atazanavir/raltegravir) were 1.95 (90% CI 1.30–2.92), 1.72 (90% CI 1.47–2.02), and 1.53 (90% CI 1.11–2.22), respectively.14,21 Conversely, raltegravir has been shown to modestly decrease the levels of atazanavir in HIV-uninfected individuals.14 Given differences in the gastric pH of HIV-infected persons, plasma concentrations are expected to be even lower in these patients. Of note, the above pharmacokinetic studies on atazanavir were conducted without ritonavir boosting. In a recent clinical trial, there was a high incidence of hyperbilirubinemia in patients taking the two medications concurrently.22 Tenofovir modestly increases plasma concentrations of raltegravir in HIV-uninfected individuals, but in HIV-1 infected individuals, the effect is attenuated. Conversely, raltegravir modestly decreases tenofovir plasma levels. None of these findings appear to be clinically significant.23 Ritonavir also does not appear to affect the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir.24 Raltegravir AUCs in coadministration studies with efavirenz, fosamprenavir, and maraviroc showed decreases of 36%, 37%, and 36% respectively compared with control subjects.14,24,25 One recent study also showed that the AUC of darunavir was decreased by up to 44% when co-administered with raltegravir.26 In all these studies, changes in the antiviral activity of both medications were not clinically significant. Dose adjustment of raltegravir with these antivirals is not warranted.

Table 1.

Summary of raltegravir interactions with selected antiretrovirals and adverse reactions with co-administration (if any)

| Antiretroviral agent | Effect on RAL levels | RAL effect on ARV levels | Adverse effects of RAL + ARV | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease inhibitors | ||||

| Atazanavir | ↑Cmin 95%, AUC 72%, Cmax 53% | ↑Cmin 29%, AUC 17%, Cmax 11% | n/a | 21 |

| Atazanavir/r | ↑Cmin 77%, AUC 41%, Cmax 24% | n/a | Hyperbilirubinemia | 21,22 |

| Fosamprenavir | ↓Cmin 38%, AUC 37%, Cmax 28% | ↓Cmin 43%, AUC 36%, Cmax 27% | None reported | 14 |

| Lopinavir/r | ↓Cmin 30%, ↑AUC 3%, Cmax 64% | ↑Cmin 4%, ↓AUC 1%, ↓Cmax 3% | None reported | 14 |

| Tipranavir/r | ↓Cmin 55%, AUC 24%, Cmax 18% | n/a | None reported | 78 |

| Darunavir/r | ↑Cmin 38%, ↓AUC 29% ↓Cmax 33% | ↓Cmin 39% | Rash | 79 |

| NRTI/NNRTI | ||||

| Abacavir | n/a | ↓Cmin 17%,↑AUC 3%, ↓Cmax 6% | None reported | 14 |

| Tenofovir | ↑Cmin 3%, AUC 49%, Cmax 64% | ↓Cmin 13%, AUC 10% Cmax 23% | None reported | 23 |

| Etravirine | ↓Cmin 34%, AUC 10%, Cmax 11% | ↑Cmin 17%, AUC 10% Cmax 4% | None reported | 80 |

| Efavirenz | ↓Cmin 21%, AUC 36%, Cmax 36% | n/a | None reported | 24 |

| CCR-5 inhibitors | ||||

| Maraviroc | ↓Cmin 28%, AUC 37%, Cmax 33% | ↓Cmin 10%, AUC 14% Cmax 20% | None reported | 14 |

Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral agents; AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; Cmin, minimum concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration; CCR-5, chemokine co-receptor 5; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; RAL, raltegravir.

Clinical trials

Treatment-naïve patients

The first published data demonstrating efficacy of raltegravir in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-1 infected humans was the first portion of the Protocol 004 study. Four groups of 6 to 8 patients were assigned to receive 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg, or 600 mg of raltegravir twice daily for 10 days as monotherapy vs placebo (n = 7). The aim of the study was to quantify the anti-retroviral activity of raltegravir, but also to assess its safety and tolerability in the short term. On day 10, the mean decrease in HIV-1 RNA was 1.9log10 copies/mL in the 100 mg group, 2.0log10 copies/mL in the 200 mg group, 1.7log10 copies/mL in the 400 mg group, and 2.2log10 copies/mL in the 600 mg group. The mean decrease in the placebo group was 0.2log10 copies/mL (P ≤ 0.001 vs raltegravir). Impressively, about 50% of the subjects in the study had achieved an HIV-1 RNA level of <400 copies/mL in the 10-day study period. The clinical significance of such a rapid decline in HIV-1 RNA in the serum is still unclear.27

Given the above results, Protocol 004 was expanded to include more treatment-naïve patients over an intended 96-week study period; 160 treatment-naïve patients (including the 26 patients from Part I) were divided into 4 groups to take 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg or 600 mg of raltegravir twice daily with an NRTI backbone of lamivudine and tenofovir. The control group was 38 patients (4 from Part I) who took 600 mg of efavirenz once daily with the same NRTI back-bone. Key patient characteristics for the 198 patients treated include a mean baseline CD4 count of 300 cells/mm3 and a baseline viral load of 4.6 to 4.8log10 HIV RNA copies/mL. The primary endpoint was the proportion in each group with HIV-1 RNA < 400 copies/mL with a secondary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA of <50 copies/mL, now the widely accepted standard for viral suppression. At 48 weeks, 85% of patients in the 100 mg twice daily group, 83% in the 200 mg group, 88% in 400 mg group, and 88% in the 600 mg group achieved HIV-1 RNA levels of <50 copies/mL. In the efavirenz group, 87% attained the same level of suppression. After 48 weeks, all raltegravir patients were switched to the subsequently FDA-approved dose of 400 mg twice daily.28 Data from 96 weeks confirmed sustained viral suppression with 83% in the raltegravir group maintaining HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL vs 84% in the efavirenz group (Table 2). CD4 count increases were also similar in both groups over the study period (221 cells/uL in raltegravir group vs 232 cells/uL in efavirenz group). Adverse event profiles were similar in both groups.29

Table 2.

Summary of major clinical studies of raltegravir

| Study | Phase | No. of participants | Study regimen | VL < 50 | CD4 countΔ | Comment/ref # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 004 | ||||||

| Part 1 | II | 35 treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients | RAL (100, 200, 400, 600 mg), or placebo twice daily for 10 days | N/A | N/A | VL ↓1.9log10 (RAL 100 mg) 2.0log10 (RAL 200 mg) 1.7log10 (RAL 400 mg) 2.2log10 (RAL 600 mg)27 |

| Part 2 | II | 198 treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients | TDF + 3TC and RAL 100, 200, 400, or 600 mg twice daily or EFV for 48 weeks | 85% (RAL 100 mg) 83% (RAL 200 mg) 88% (RAL 400 mg) 88% (RAL 600 mg) 87% (EFV) |

↑221 (100 mg) ↑146 (200 mg) ↑144 (400 mg) ↑187 (600 mg) ↑170 (EFV) |

28 |

| Extension | II | 198 treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients | TDF + 3TC and RAL 400 mg twice daily or EFV for 96 weeks | 83% (RAL) 84% (EFV) |

↑221 (RAL) ↑232 (EFV) |

29 |

| STARTMRK | ||||||

| 48 weeks | III | 563-treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients | TDF + FTC and RAL 400 mg twice daily of EFV | 86% (RAL) 82% (EFV) |

↑189 (RAL) ↑163 (EFV) |

30 |

| 96 weeks | III | 477 treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients | Same as above | 81% (RAL) 79% (EFV) |

↑240 (RAL) ↑225 (EFV) |

31 |

| Protocol 005 | ||||||

| 24 weeks | II | 178 treatment-experienced, HIV-1-infected patients | OBT plus RAL (200, 400, or 600 mg) twice daily or placebo | 65% (RAL 200 mg) 56% (RAL 400 mg) 67% (RAL 600 mg) 13% (placebo) |

↑63 (200 mg) ↑113 (400 mg) ↑94 (600 mg) ↑5.4 (placebo) |

32 |

| 96 weeks | same as above | OBT plus RAL 400 mg twice daily or placebo | 55% (RAL) | ↑104 (RAL) | 33 | |

| BENCHMRK | ||||||

| 48 weeks Trial 1 |

III | 350 treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected patients | OBT and RAL 400 mg twice daily or placebo | 65% (RAL) 31% (placebo) |

↑109 (RAL) ↑45 (placebo) (Trial 1 and 2) |

34 |

| Trial 2 | 349 treatmentexperienced HIV-1-infected patients | Same as above | 60% (RAL) 35% (placebo) |

See above | ||

| 96 weeks (Trial 1 and 2) | III | 699 treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected patients | Same as above | 57% (RAL) 26% (placebo) |

↑123 (RAL) ↑49 (placebo) |

35 |

| SWTCHMRK | III | 702 HIV-1-infected patients with viral suppression on LPV/r-based regimen | OBT + LPV/r or switch to OBT + RAL for 24 weeks | 84% (RAL) 91% (control) |

↑5–17 (both groups) | 58 |

| SPIRAL | III | 273 HIV-1-infected patients with viral suppression on PI-based regimen | OBT + PI/r or switch to RAL for 48 weeks | 89% (RAL) 87% (control) |

↑46 (RAL) ↑44 (placebo) |

59 |

| SHIELD | II | 35 treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected patients | Single arm of ABC/3TC + RAL for 48 weeks | 91% | ↑247 | First study looking at RAL with alternative NRTI background62 |

| SPARTAN | II | 93 treatment-naïve HIV-1 infected-patients | ATV/RAL or ATV/r + TDF/FTC for 24 wks | 75% (ATV/RAL) 63% (ATV/r + TDF FTC) |

Not reported | Terminated early due to resistance in ATV/RAL group, hyperbilirubinemia22 |

Abbreviations: ATV, atazanavir; ABC, abacavir; 3TC, lamivudine; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; OBT, optimized background therapy; PI, protease inhibitor; RAL, raltegravir; TDF, tenofovir; VL, viral load.

Given the success of the Phase II studies, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial (STARTMRK) was initiated to establish noninferiority of a raltegravir-based regimen vs the established treatment standard efavirenz-based regimen. A total of 563 patients was randomized to receive either raltegravir 400 mg twice daily or efavirenz 600 mg once daily. Both groups also received a fixed dose combination emtricitabine/tenofovir NRTI backbone as part of the regimen. Key patient characteristics included a mean baseline viral load of 5.0log10 HIV RNA copies/mL, with 53% of the patients having a baseline viral load > 100,000 copies per/mL. The mean age of the study population was 37.3 years. Of the study participants, 18% were women and 42% were white; 48% had a CD4 count of <200 cells/uL. The primary endpoint was viral suppression < 50 copies/mL HIV RNA. After 48 weeks, 86.1% of the raltegravir group achieved the primary endpoint compared with 81.9% of the efavirenz group. As in prior trials, time to viral suppression was much shorter in the raltegravir group.30 Of patients from the initial trial period, 84% remained in the study for 96-weeks follow up. In the intention-to-treat analysis, all noncompleters were treated as failures. At 96 weeks, 81% of the patients in the raltegravir group and 79% of the patients in the efavirenz group maintained HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/uL. Although there was a significantly higher increase in CD4 count in the raltegravir group at 48 weeks, the difference between the groups did not meet statistical significance at 96 weeks (240 cells/μL vs 225 cells/μL in the raltegravir and efavirenz groups respectively, Δ 15 cells, 95% CI −13 to 42) (Table 2). Patients in the efavirenz group had significantly more drug-related adverse events as well. This disparity was mostly accounted for by the well-documented central nervous system side effect profile of efavirenz.31 In light of the above results, raltegravir was approved by the FDA to treat antiretroviral-naïve HIV- 1-infected patients on July 9, 2009.

Treatment experienced patients

The Protocol 005 study was a phase II, double-blind clinical trial, which investigated the safety and efficacy of raltegravir in combination with optimized background regimens (OBT) in HIV-infected patients with multidrug-resistant virus. Patients enrolled in the study were required to be infected with HIV documented to be resistant to at least one NNRTI, one NRTI, and one protease inhibitor (PI). Patients also had to be on a stable antiretroviral regimen for at least 3 consecutive months before enrollment. The screening entry viral load threshold was 5000 copies/mL with a CD4 count of at least 50 cells/μL. A total of 179 patients were enrolled in the study including 44 who received raltegravir 200 mg twice daily + OBT, 45 assigned to 400 mg twice daily + OBT, and 45 who received 600 mg twice daily + OBT. Another 45 patients were randomized to receive placebo + optimized background therapy. The quality of the selected OBT was stratified by genotypic and phenotypic sensitivity, with a score of “1” representing one drug to which the virus was fully sensitive. From this a summative genotypic and phenotypic sensitivity score (GSS and PSS) was derived (Table 3). The primary endpoint was change in viral load from baseline at 24 weeks. At the primary endpoint (24 weeks), the mean decrease from baseline viral load in the raltegravir groups was −1.80log10 in the 200 mg group, −1.87log10 for the 400 mg group and −1.84log10 for the 600 mg group. The baseline viral load decrease in the placebo group was 0.35log10. The proportion of patients who achieved a viral load < 50 copies at week 24 was 65% in the 200 mg raltegravir arm, 56% in the 400 mg arm, and 67% in the 600 mg arm. Only 16% of those assigned to the placebo group reached this level of viral suppression at 24 weeks. Adverse event profiles were similar in all groups.32 Subsequently, Protocol 005 was extended to an open label phase for a follow-up period of 96 weeks. All patients from the double-blind phase were offered the opportunity to continue raltegravir at 400 mg twice daily. Eighty-six patients from the raltegravir group and 6 patients from the placebo group completed 96 weeks of raltegravir 400 mg twice daily, 48% of whom achieved HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/μL at 96 weeks. The mean increase in CD4 count in the group was 104 cells/μL at 96 weeks.33

Table 3.

Response to raltegravir based on Genotypic (GSS) and Phenotypic Sensitivity Score (PSS) in BENCHMRK Trials

| HIV RNA level < 50 copies/mL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raltegravir group | Placebo group | |

| Genotypic sensitivity score | ||

| 48 weeks | ||

| 0 | 45% | 3% |

| 1 | 67% | 37% |

| 2 | 77% | 62% |

| 3 or more | 71% | 52% |

| 96 weeks | ||

| 0 | 41% | 5% |

| 1 | 72% | 28% |

| 2 | 70% | 61% |

| ≥3 | 53% | 38% |

| Phenotypic sensitivity score | ||

| 48 weeks | ||

| 0 | 51% | 2% |

| 1 | 61% | 29% |

| 2 | 71% | 39% |

| 3 | 71% | 61% |

| 96 weeks | ||

| 0 | 48% | 5% |

| 1 | 65% | 24% |

| 2 | 69% | 35% |

| 3 | 54% | 48% |

Note: Genotypic (GSS) and Phenotypic Sensitivity score is a measure of how many drugs are active against the subject’s virus. For example, a GSS of ‘1’ denotes that the patient has one drug determined to be active based on serum HIV-1 genotype assay against the subject’s virus.

Given the favorable results of the phase II trial, the BENCHMRK trials were initiated with the purpose of validating the antiretroviral efficacy of raltegravir as part of an optimized treatment regimen for HIV-infected patients with multi-drug resistant virus. BENCHMRK-1 and 2 were identical trials organized simultaneously in two different geographical regions. BENCHMRK-1 was conducted in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Peru, while BENCHMRK-2 was organized mainly in North and South America. A total of 699 patients participated in these studies, 462 randomized to raltegravir 400 mg twice daily + OBT and 237 randomized to placebo + OBT. As in Protocol 005, all enrollees had to be infected with HIV-1 virus resistant to at least one PI, one NNRTI, and one NRTI. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved viral load of <400 copies/ mL at weeks 16 and 48. At any point in the study after week 16, patients in the placebo arm had the opportunity to enter an open-label phase to receive raltegravir as part of their ARV regimen. At week 16, 77.5% of patients in the raltegravir group and 41.9% of patients in the placebo group achieved viral loads of <400 copies/uL; 61.8% of the raltegravir group and 34.7% of the placebo group reached a viral load of <50 copies/mL. At 48 weeks, 62.1% of the raltegravir group maintained viral loads <50 copies/mL compared with 32.9% of the placebo group (P < 0.001).34 Both studies were extended to 96 weeks. Of the raltegravir recipients, 57% achieved a viral load of <50 copies/mL at 96 weeks compared with 26% of remaining on placebo. The mean increase in the CD4 count was 123 cells/uL in the raltegravir group and 49 cells/uL in the placebo group. Interestingly, 41% of patients with a genotypic sensitivity score (GSS) of ‘0’ maintained viral loads <50 copies/mL at week 96, suggesting that this subset of patients achieved viral suppression essentially on raltegravir monotherapy (Table 3). Although an interesting finding, raltegravir monotherapy is still not recommended in patients with multi-resistant virus as some of the other agents had partial antiretroviral activity even in the presence of extensive in vitro resistance.35 Given the results of the BENCHMRK studies, raltegravir was granted accelerated approval for use in the treatment of patients with multiresistant HIV virus by the FDA on October 12, 2007.

Safety and tolerability

A trial of 35 HIV-infected patients who received raltegravir for 10 days showed that the adverse effect profile of raltegravir was similar to placebo. The only drug-related laboratory abnormality was an elevation in alanine aminotransminase in one patient. This abnormality resolved without interruption in therapy.27 In the 96-week follow-up period of Protocol 004, 51% of patients taking raltegravir reported adverse events that were judged by the investigators to be drug-related. Most of these events were mild, including headaches, nausea, and diarrhea. In the raltegravir group, 10 patients (6.3%) experienced significant elevations in creatine phosphokinase (CPK), greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN). This was only reported in 3% of patients in the efavirenz group. Only four of the 10 cases were judged to be drug-related and there were no reports of rhabdomyolysis. Raltegravir was stopped temporarily in one patient. Overall, 51% of the patients in the raltegravir group vs 74% of the patients in the efavirenz group had any drug-related adverse events. In contrast to the lipid elevations seen in the efavirenz arm, lipid profiles in the raltegravir group were virtually unchanged from baseline after 96 weeks.29

The Phase III STARTMRK study validated most of the findings in Protocol 004. 47% of patients in the raltegravir group experienced adverse events judged to be drug-related at 96 weeks. This was significantly lower than in the efavirenz group in which 78% of the patients reported a drug-related adverse event. There was one reported case of severe myopathy in a patient receiving raltegravir during the study period. The patient recovered without discontinuation of raltegravir. The most common drug-related adverse event in the raltegravir groups was headache (3.9% of patients). As in Protocol 004, there were no significant changes in lipid profile from baseline in the raltegravir group after 96 weeks. Changes in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were smaller in the raltegravir group than in the efavirenz group (P < 0.001).34,36

In the Phase II Protocol 005 study of HIV-1 infected patients with multi-resistant virus, the adverse event profile of the raltegravir + OBT group was similar to that of placebo + OBT, a finding validated by the safety data from the larger Phase III BENCHMRK studies. Again, Grade 4 CPK elevations (>20 × ULN), were more common in the raltegravir group than in the placebo group (3% vs 0.8% in placebo), but none of these cases were associated with rhabdomyolysis or clinically apparent myopathy.33

In the first 3 years after FDA approval, four cases of rhabdomyolysis suspected to be caused by raltegravir were reported in the literature. There was considerable variability in the duration of exposure to raltegravir before the onset of rhabdomyolysis in these cases, ranging from 10 days to 23 months. Most importantly, all four of the reported patients had significant risk factors predisposing them to myopathies of any cause at the time of raltegravir initiation. The first patient had chronic renal insufficiency (SCr of 2.3) and was receiving concomitant intravitreal foscarnet injections for cytomegalovirus retinitis.37 The second patient was taking pravastatin and tenofovir at baseline.38 The other two patients were co-infected with hepatitis C virus, one of whom had documented elevations in creatine kinase on a previously received nonraltegravir-based regimen.39,40 Given these conditions, causation could not be definitively established in any of the cases. Nevertheless, raltegravir should be used with caution or not at all in individuals at increased risk of myopathies, as recommended by the FDA and the drug manufacturer.2

Resistance to raltegravir

As with other classes of antiretrovirals, integrase inhibitors are subject to the dynamic adaptablility of the HIV-1 viral genome.11,41 All the major mutations responsible for decreased susceptibility to raltegravir appear to localize around the active site of the IN enzyme.42 In vitro data suggest that an accumulation of mutations in the IN enzyme is necessary before phenotypic resistance to raltegravir is conferred.43,44 Distinct subsets of mutations in the IN enzyme have been characterized in the viral sequences of patients who have failed raltegravir. The primary mutations have been identified as Q148H, N155H, and Y143R/C, with the major secondary mutations being E92Q and G140S. All these amino acid residues correspond to the active site of the IN enzyme.45–47 Genotypic sequencing studies in serum samples of 67 BENCHMRK patients who failed raltegravir revealed that the Q148H and N155H integrase mutations were mutually exclusive. Furthermore, the secondary mutation E92Q invariably clustered with the N155H mutation while the G140S tended to be found in the Q148H mutants.36

Further investigations showed that the secondary integrase mutations enabled a selection advantage (Table 4).48–51 All the aforementioned mutations confer decreased phenotypic susceptibility to raltegravir alone; however, viruses with these mutations have substantial decreases in their replicative capacity in the absence of raltegravir compared with wildtype virus. The secondary mutations appear to amplify the resistance of the virus to raltegravir while also restoring the replicative capacity of Q148H mutant virus essentially to wild-type virus levels.50,51

Table 4.

| HIV integrase mutation | Fold change from WT RAL IC50 |

|---|---|

| N155H | 16 |

| Q148H | 18 |

| Q148R | 34 |

| Y143R | ~30 |

| N155H + E92Q | >150 |

| Q148H + G140S | 521 |

| Q148H + E138K | 20 |

| Q148H + G140A | >150 |

| Q148R + G140S | 405 |

| Q148R + E138K | >150 |

| Q148R + G140A | >150 |

Abbreviations: IC50, concentration of raltegravir at which 50% of integrase strand transfer activity is inhibited in vitro; RAL, raltegravir; WT, wild-type.

The prominence of these distinct mutations has been corroborated by clinical data. Genotypic sequencing was conducted on 94 of 105 raltegravir recipients who failed raltegravir by week 48 in the BENCHMRK trials; 67% of these patients had mutations at either amino acid 148, 155, or 143. Among this subset of patients, 30% had the Q148H mutation and 43% had a mutation at residue 155.36 As previously noted, the N155H single mutant has a slightly enhanced viral fitness in the absence of raltegravir than Q148H. However, addition of G140S to Q148H gives it a substantial fitness advantage over N155H. More importantly, the G140S mutation gives the Q148H mutant an IC50 that is five times greater than the E92Q/N155H double mutant, 20 times greater than the Q148H single mutant, and 245 times greater than wild-type.50 Longitudinal clonal analysis of virus isolated from HIV-1 patients who failed raltegravir has shown that in early virologic failure, the N155H mutant is prominent.52 However, selection pressure of subsequent exposure to raltegravir favors the predominance of the Q148H/ G140S mutant over time.53,54 Q148H, N155H, or Y143C were almost never identified in the integrase sequence of raltegravir-naïve patients.55,56 The above mutations have also been shown to confer some degree of resistance to all the current integrase inhibitors in development, including elvitegravir, and second generation integrase inhibitors MK-2048 and GSK-572. These mutations have not been shown to affect the efficacy of antiretrovirals of any other class to date.57

Current considerations in the clinical use of raltegravir

Given the substantial clinical evidence that raltegravir has minimal effect on lipid profiles compared with other classes of antiretrovirals, a series of studies was conducted to investigate whether switching from a PI-based to a raltegravir-based regimen maintained viral suppression. The largest studies were the SWITCHMRK trials. The goal of these trials was to determine whether patients who achieved viral suppression on lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) could maintain viral suppression at acceptable levels after switching to raltegravir while at the same time achieving improvements in lipid profiles (the primary endpoint of the SWITCHMRK study). Seven hundred and two patients were evenly randomized to receive raltegravir or maintain their current lopinavir/r based regimen. All participants were required to have achieved viral suppression on a LPV/r based regimen for at least 3 months prior to randomization. In the combined trials (SWITCHMRK 1 and 2), 84.4% of the patients who switched to raltegravir maintained viral loads < 50 copies/mL at 24 weeks, compared with 90.6% of patients who stayed on LPV/r. The lower limits of the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the raltegravir group and the LPV/r group in SWITCHMRK 1 and 2 studies were −14.4% and −12.2%, respectively. Both these values exceeded the predetermined study threshold of noninferiority which was −12%, thus establishing inferiority of the switch strategy.58 The SPIRAL study, conducted primarily in Spain, looked into the same question: 273 patients were randomized either to remain on their protease inhibitor-based regimen or switch to raltegravir. In contrast to the SWITCHMRK study population, the median time of viral suppression before randomization in the SPIRAL study was 73 months. In this study, 89% of the raltegravir group and 87% of the PI group maintained viral suppression < 50 copies/mL after 48 weeks, confirming the noninferiority of raltegravir in this study. The authors of the SPIRAL study speculate that longer periods of viral suppression in their cohort at the time of study enrollment may be the primary reason why their raltegravir group had better outcomes than in SWITCHMRK. In SWITCHMRK, the average duration of time on antiretroviral therapy for patients who switched to raltegravir was 3.4 years.58,59 Clinical data assessing the potential for successful switch of virologically suppressed patients from enfurvitide to raltegravir have been more definitively shown to be safe and effective.60,61

The success of raltegravir in these various situations has prompted other studies looking at other less commonly used strategies. Raltegravir has recently shown efficacy when administered with alternate NRTI backgrounds. Data from the SHIELD study (RAL+lamivudine/abacavir) showed that 31 of 35 HIV-1 treatment-naïve patients achieved viral suppression of <50 copies/mL at 48 weeks.62 Recent studies investigating the efficacy of raltegravir-based NRTI sparing regimens have produced varying results. The SPARTAN study randomized treatment-naïve HIV-infected subjects to receive either unboosted atazanavir and raltegravir or ritonavir boosted atazanavir + emtricitabine/tenofovir, one of the four “preferred” regimens in the 2011 DHHS guidelines. The trial was terminated prematurely due to higher rates of antiretroviral resistance among those with virologic failure and unacceptably high levels of hyperbilirubinemia in the atazanavir/ raltegravir group.22 The ongoing PROGRESS study is a 96-week trial comparing the combination of LPV/r and raltegravir to a regimen of LPV/r and tenofovir plus emtricitabine in treatment-naïve patients. According to 48-week data from this trial, 83% of patients in the RAL arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV RNA < 40 copies/ml vs 85% in the TDF/FTC group, thus suggesting noninferiority.63 ACTG A5262 was a single-arm clinical trial that looked into the use of a novel combination of raltegravir and ritonavir-boosted darunavir in treatment-naïve patients. Surprisingly, in the 48 week intention-to-treat analysis, only 62% of the 112 patients achieved viral load of <50 copies/mL (28 virologic failures, 15 discontinued trial prematurely). Although this was a single-arm study, the proportion of noncompleters during the study period raises concern.64 Investigations in a humanized mouse model have shown successful prophylaxis from HIV-1 when the animals were administered species-equivalent doses of raltegravir. However, this was a proof-of-concept study and its clinical applicability is likely far in the future.65 Recent attempts at using raltegravir dose intensification to eradicate latent HIV reservoirs have proven to be unsuccessful.66–68 Raltegravir has been shown to have activity against xenotropic murine leukemia-related retrovirus, a virus that may be associated with prostate cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome.69

A significant disadvantage to the clinical use of raltegravir is the requirement for twice-daily dosing to achieve maximal efficacy.2 Recent studies have shown that raltegravir is less efficacious in achieving and maintaining viral suppression when dosed once daily.70 The most important such study was the QDMRK study which demonstrated the drug’s loss of antiviral activity with once daily dosing. In this study, 770 treatment-naïve patients were randomized to receive either raltegravir 400 mg twice daily or raltegravir 800 mg once daily. Both groups received tenofovir/emtricitabine as NRTI backbone. At 48 weeks, 88.9% of twice daily group achieved viral load < 50 copies/mL compared with 83.2% of the patients in the once daily group. The treatment difference was −5.7% (95% CI, −10.7% to −0.8%), thus establishing inferiority of once daily dosing over the approved twice daily regimen. In patients with a baseline viral load of >100,000 copies/mL, 84.2% of patients achieved viral load < 50 copies/ mL with twice daily dosing compared with 74.3% in the once daily group. There was no statistically significant difference between the dosage groups in patients with baseline viral load of < 100,000 copies/uL.71

Elvitegravir (GS-9137), is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase activity developed by Gilead Sciences. When boosted by ritonavir, elvitegravir’s systemic exposure is increased by 20-fold, thus allowing persistent plasma levels suitable for once daily dosing.61 Phase II clinical trials showed that elvitegravir achieved viral suppression rates comparable to that of a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor at 24 weeks. Phase III studies on this drug are ongoing.72 Interestingly, elvitegravir appears to exhibit decreased activity against when the integrase gene has the Q148H/G140S as well as the N155H/E92Q mutations.53,57 The investigational integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (formerly known as S/GSK1349572, Shionogi/Glaxo Smith Kline) has been shown in phase I/II trials to have excellent activity in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-infected patients. It also appears to have significant antiviral activity against HIV viruses with some patterns of resistance after viral failure of raltegravir. Early data from the VIKING trial show potent antiviral activity in many patients who had previously failed raltegravir. The primary short-term endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved a viral load < 400 copies/mL or 0.7log10 change of viral load below their baseline value after 10 days of therapy. In VIKING I, patients were given dolutegravir 50 mg once daily + OBT; 78% of these patients achieved the primary endpoint on Day 11. Interestingly, all of the six patients who failed to reach the endpoint harbored the Q148H mutation. When dolutegravir was given at 50 mg twice daily in VIKING II, 96% of these patients achieved the primary endpoint, including all of the patients with Q148H.73,74 Data at 24-weeks for the VIKING trials are pending. Nevertheless, potent antiviral activity against raltegravir-resistant virus as well as its long half-life without the need for pharmacologic boosting makes it a promising prospect as part of a new generation of integrase inhibitors.75

Role in therapy

Extensive clinical data have shown the efficacy of raltegravir in the management of HIV-infection in both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients. Accordingly, raltegravir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir has been named as one of the “preferred” regimens for initial therapy of HIV-infected patients, in the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines as updated in January 2011.76 As stated above, ongoing studies are being conducted to confirm its safety and efficacy with other NRTI combinations.61 It’s favorable side effect profile in comparison to all other antiretrovirals as well as its minimal impact in lipid homeostasis has made it a strong option for the treatment of an array of HIV-1 infected patients. Raltegravir’s efficacy in highly treatment-experienced patients highlight the drug’s versatility. Given the availability of other potent and safe antiretroviral regimens for treatment-naïve patients, some clinicians prefer to reserve raltegravir for patients with multiply drug-resistant HIV infection. Others believe the advantages of raltegravir should be exploited early in the treatment sequence. Reports of the long-term success of etravirine, raltegravir, and boosted darunavir salvage regimens in patients with highly resistant HIV are intriguing.77 Enthusiasm for more widespread use of raltegravir is tempered by cost considerations in some settings. Nevertheless, raltegravir’s generally favorable safety profile and its superior potency in suppression of HIV-1 replication will likely ensure its place in the range of successful HIV-1 antiretroviral treatment options for years to come.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr Hicks has received grant/research support and/or served as a consultant for the following commercial entities: Argos, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Registrat MAPI, Tibotec, ViiV.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Global summary of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. 2009. [Accessed December 10, 2010]. http://www.who.int/hiv/data/en.

- 2.Isentress (raltegravir) [package insert] Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pommier Y, Johnson AA, Marchand C. Integrase inhibitors to treat HIV/ AIDS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:236–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoder KE, Bushman FD. Repair of gaps in retroviral DNA integration intermediates. J Virol. 2000;74:11191–11200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11191-11200.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazuda DJ, Felock PJ, Hastings JC, et al. Differential divalent cation requirements uncouple the assembly and catalytic reactions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1997;71:7005–7011. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7005-7011.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fesen M, Kohn K, Leteurtre F, Pommier Y. Inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2399–2403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey K, Grandgenett D. HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors: novel insights into their mechanism of action. Retrovirology. 2008;2:11–16. doi: 10.4137/rrt.s1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McColl DJ, Chen X. Strand transfer inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase: bringing IN a new era of antiretroviral therapy. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:101–118. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobler JA, Stillmock K, Hu B, et al. Diketo acid inhibitor mechanism and HIV-1 integrase: implications for metal binding in the active site of phosphotransferase enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6661–6666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092056199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazuda DJ, Felock P, Witmer M, et al. Inhibitors that prevent integration and inhibit HIV-1 replication in cells. Science. 2000;287:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu K, Dobard C, Chow SA. Requirement for integrase during reverse transcription of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 and the effect of cysteine mutations of integrase on its interactions with reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 2004;78:5045–5055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5045-5055.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazuda DJ, Anthony NJ, Gomes RP, et al. A naphthyridine carboxamide provides evidence for discordant resistance between mechanistically identical inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11233–11238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402357101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Summa V, Petrocchi A, Bonelli F, et al. Discovery of raltegravir, a potent selective orally bioavailable HIV-integrase inhibitor for the treatment of HIV-AIDS infection. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5843–5855. doi: 10.1021/jm800245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brainard DM, Wenning LA, Stone JA, Stone, et al. Clinical pharmacology profile of raltegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 Jan 1–26; doi: 10.1177/0091270010387428. Epub 2011 Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwamoto M, Hanley WD, Petry AS, et al. Lack of a clinically important effect of moderate hepatic insufficiency and severe renal insufficiency on raltegravir pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1747–1752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01194-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francisci D, Martinelli L, Weimer LE, et al. HIV-2 infection, end stage renal disease and protease inhibitor intolerance: which salvage regimen? Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:345–349. doi: 10.1007/BF03256933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molto J, Sanz-Moreno J, Valle M, et al. Minimal removal of raltegravir by hemodialysis in HIV-infected patients with end stage renal disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3047–3048. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00363-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yilmaz A, Gisslen M, Spudich S, et al. Raltegravir cerebrospinal fluid concentrartions in HIV-1 1 infection. PloS One. 2009;4:e6877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto M, Kassahan K, Matthew D, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic effect of raltegravir on midazolam: in vitro/in vivo correlation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:209–214. doi: 10.1177/0091270007310382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenning LA, Hanley WD, Brainard DM, et al. Effect of rifampin, a potent inducer of drug metabolizing enzymes, on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2852–2856. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01468-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamoto M, Wenning L, Mistry GC, et al. Atazanavir modestly increases plasma levels of raltegravir in healthy adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:137–140. doi: 10.1086/588794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozal MJ, Lupo S, DeJesus E, et al. The SPARTAN study: a pilot study to assess the safety and efficacy of an investigational NRTI and RTV-sparing regimen of atazanavir experimental dose of 300 mg bid plus raltegravir 400 mg bid in treatment naïve HIV-infected patients. [Abstract No. THLBB204]. programs and abstracts of the 18th International AIDS Conference (Vienna); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenning L, Friedman E, Kost J, et al. Lack of significant drug interaction between raltegravir and tenofovir. Antomicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3253–3258. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00005-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwamoto M, Wenning L, Petry A, et al. Minimal effects of ritonavir and efavirenz on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4338–4343. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrail-Tran A, Yazdanpanah Y, Goldwirt L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of etravirine, raltegravir and darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experience patients. AIDS. 2010;24:2581–2593. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32833d89fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, Ragazzoni E, et al. Darunavir/ritonavir and raltegravir coadministered in routine clinical practice: potential role for an unexpected drug interaction. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markowitz M, Morales-Ramirez JO, Nguyen BY, et al. Antiretroviral activity, pharmacokinetics, and tolerability of MK-0518, a novel inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase, dosed as monotherapy for 10 days in treatment-naïve HIV-1 individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:509–515. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802b4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markowitz M, Nguyen BY, Gotuzzo E, et al. Rapid and durable antiretroviral effect of HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir as part of combination therapy in treatment-naïve patients with HIV-1 infection: results of a 48-week controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:125–133. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318157131c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowitz M, Nguyen BY, Gotuzzo E, et al. Sustained antiretroviral effect of raltegravir after 96 weeks of combination therapy in treatment-naïve patients with HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:350–356. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b064b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lennox JL, Dejesus E, Lazzarin A, et al. Safety and efficacy of raltegravir-based versus efavirenz-based combination therapy in treatment naïve patients with HIV-1 infection: a multicentre, double-blind randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:796–806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Berger DS, et al. Raltegravir versus efafirenz regimens in treatment-naïve HIV-1 infected patients: 96-week efficacy, durability, subgroup, safety and metabolic analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:39–47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181da1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grinstejn B, Nguyen BY, Katlama C, et al. Safety and efficacy of the HIV-1 integrase inhibitor raltegravir (MK-0518) in treatment-experienced patients with multdrug-resistant virus : a phase II randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gatell JM, Katlama C, Grinzstejn B, et al. Long term efficacy and safety of the HIV integrase inhibitor raltegravir in patients with limited treatment options in a phase II study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:456–463. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181c9c967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steigbigel R, Cooper D, Kumar P, et al. Raltegravir with optimized background therapy for resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:339–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steigbigel R, Cooper DA, Teppler H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of raltegravir combined with optimized background therapy in treatment-experienced patients with drug-resistant HIV infection: week 96 results of the BENCHMRK 1 and 2 Phase III trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:605–612. doi: 10.1086/650002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper DA, Steigbigel R, Gatell JM, et al. Subgroup and resistance analyses of raltegravir for resistant HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:355–365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zembower TR, Gerzenshtein L, Coleman K, et al. Severe rhabdomyolysis associated with raltegravir use. AIDS. 2008;22:1382–1383. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328303be40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dori L, Buonomoni AR, Viscione M, et al. A case of rhabdomyolysis associated with raltegravir use. AIDS. 2010;24:473–474. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328334cc4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croce F, Vitello P, Pria D, et al. Severe raltegravir-associated rhabdomyolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Intl J STD AIDS. 2010;21:783–785. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masia M. Severe acute renal failure associated with rhabdomyolysis during treatment with raltegravir: a call for caution. J Infect. 2010;61:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerton J, Ohgi S, Olsen M, et al. Effects of mutations in residues near the active site of human immunodeficiency virus type I integrase on specific enzyme-substrate interactions. J Virol. 1998;72:5046–5055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5046-5055.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazuda DJ. Resistance to inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. Brazil J Infect Dis. 2010;14:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fikkert V, Van Maele B, Vercammen J, et al. Development of resistance against diketo derivatives of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by progressive accumulation of integrase mutations. J Virol. 2003;77:11459–11470. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11459-11470.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fikkert V, Hombrouck A, Van Remoortel B, et al. Multiple mutations in human immunodeficiency virus-1 integrase confer resistance to the clinical trial drug S-1360. AIDS. 2004;18:2019–2028. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fransen S, Gupta S, Danovich R. Loss of raltegravir susceptibility by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is conferred via multiple nonoverlapping genetic pathways. J Virol. 2009;83:11440–114446. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01168-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reigadas S, Anies G, Maquelier B, et al. The HIV-1 integrase mutations Y143C/R are an alternative pathway for resistance to raltegravir and impact the enzyme functions. PloS One. 2010;5:e10311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delelis O, Thierry S, Subra F, et al. Impact of Y143 HIV-1 integrase mutations on resistance to raltegravir in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:491–501. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01075-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malet I, Delelis O, Soulie C, et al. Quasispecies variant dynamics during emergence of resistance to raltegravir in HIV-1 infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:795–804. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quercia R, Dam E, Perez-Bercoff D, et al. Selective advantage profile of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants explains in vivo evolution of raltegravir resistance genotypes. J Virol. 2009;83:10245–10249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00894-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Z, Kuritzkes D. Effect of raltegravir resistance mutations in HIV-1 integrase on viral fitness. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:148–155. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9a87a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hatano H, Lampiris H, Fransen S, et al. Evolution of integrase resistance during failure of integrase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:389–393. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c42ea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fransen S, Karmochkine M, Huang W, et al. Longitudinal analysis of raltegravir susceptibility and integrase replication capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during virologic failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4522–4524. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garrido C, Geretti A, Zahonero N, et al. Integrase variability and susceptibility to HIV integrase inhibitors: impact of subtypes, anti-retroviral experience and duration of HIV infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:320–326. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Codoner F, Pou C, Thielen A, et al. Dynamic escape of pre-existing raltegravir-resistant HIV-1 from raltegravir selection pressure. Antiviral Res. 2010;88:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Low A, Prada N, Topper M, et al. Natural polymorphisms of human immunodeficiency virus type I integrase and inherent susceptibilities to a panel of integrase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4275–4282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00397-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sliberstein-Ceccherini F, Malet I, Fabeni L, et al. Specific HIV-1 integrase polymorphism change their prevalence in untreated versus antiretroviral-treated HIV-1 infected patients, all naïve to integrase inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2305–2318. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goethals O, Clayton R, Van Ginderen M, et al. Resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selected with elvitegavir confer reduced susceptibility to a wide range of integrase inhibitors. J Virol. 2008;82:10366–10374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00470-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eron JJ, Young B, Cooper DA, et al. Switch to a raltegravir-based regimen versus continuation of a lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen in stable HIV-infected patients with suppressed viremia (SWITCHMRK 1 and 2): two multicentre, double-blind, randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;375:396–407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martinez E, Larrousse M, Llibre JM, et al. Substitution of raltegravir for ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors in HIV-infected patients: the SPIRAL study group. AIDS. 2010;24:1697–1707. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a608a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Towner W, Klein D, Kerrigan HL, et al. Virologic outcomes of changing enfurvitide to raltgravir in HIV-1 patients well controlled on an enfurvitide based regimen: 24 week results of the CHEER study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:367–373. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ae35de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powderly WG. Integrase inhibitors in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2485–2488. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young B, Vanig T, DeJesus E, et al. A pilot study of abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC) and raltegravir in antiretroviral naïve HIV-1 infected subjects: 48 week results. [Abstract THPE0112]. program and abstracts of the 18th International AIDS Conference (Vienna); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynes J, Lawal A, Pulido F, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir combined with raltegravir demonstrated similar antiviral efficacy and safety as lopinavir/ ritonavir combined with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/ emtricitabine in treatment-naïve HIV-1 infected subjects. Program and abstracts of the XVIII International AIDS Conference; July 18–23, 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract MOAB0101. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taiwo B, Zheng S, Gallien S, et al. Results of a single-arm study of DRV/r + RAL in treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected patients (ACTG A5262). Program and abstracts of the 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Feb 2011; Boston, USA. Paper 551. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neff CP, Ndolo T, Tandon A, et al. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis by anti-retrovirals raltegravir and maraviroc protects against HIV-1 vaginal transmission in a humanized mouse model. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gandhi R, Zheng Lu, Bosch R, et al. The effect of raltegravir intensification on low-level residual viremia in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. PloS One. 2010;7:e1000321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMahon D, Jones J, Wiegand A, et al. Short-course raltegravir intensification does not reduce persistent low-level viremia in patients with HIV-1 suppression during receipt of combination antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:912–919. doi: 10.1086/650749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buzon MJ, Massanella M, Llibre J, et al. HIV-1 replication and immune dynamics are affected by raltegravir intensification of HAART-suppressed subjects. Nat Med. 2010;16:460–466. doi: 10.1038/nm.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh IR, Gorzynski JE, Drobysheva D, et al. Raltegravir is a potent inhibitor of XMRV, a virus implicated in prostate cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome. PloS One. 2010;5:e9948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vispo R, Barreiro, Maida I, et al. Simplification from protease inhibitors to once or twice daily raltegravir: the ODIS trial [Abstract No. MOAB0102]. program and abstracts of the 18th International AIDS Conference (Vienna); 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eron J, Rockstroh J, Reynes J, et al. QDMRK, a Phase III study of the safety and efficacy of once daily vs twice daily RAL in combination cherapy for treatment-naïve HIV-infected patients. Program and abstracts of the 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Feb 2011; Boston, USA. Abstract 150LB. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zolopa AR, Berger DS, Lampiris H, et al. Activity of elvitegravir, a once-daily integrase inhibitor, against resistant HIV type 1: results of a phase 2, randomized, controlled, dose-ranging clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:814–822. doi: 10.1086/650698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eron J, Durant J, Poizot-Martin I, et al. Activity of a next generation integrase inhibitor (INI), S/GSK1349572, in subjects with HIV exhibiting raltegravir resistance: initial results of VIKING study (ING112961). Program and abstracts of the XVIII International AIDS Conference; July 18–23, 2010; Vienna, Austria. Abstract MOAB0105. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eron J, Kumar P, Lazzarin A, et al. DTG in subjects with HIV exhibiting RAL resistance: functional monotherapy results of VIKING study cohort II. Program and abstracts of 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Feb 2011; Boston, USA. Paper 151LB. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kobayashi M, Yoshinaga T, Seki T, et al. In vitro antiretroviral properties of S/GSK1349572 a next generation HIV integrase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:813–821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01209-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DHHS Panel-Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council. US Department of Health and Human Services 2009. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. [Accessed December 28, 2010]. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdoslescentGL.pdf.

- 77.Nakamura H, Miyazaki N, Hosoya N, et al. Long-term successful control of super-multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by a novel combination therapy of raltegravir, etravirine and boosted darunavir. J Infect Chemother. 2011;17:105–110. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanley WD, Wenning LA, Moreau, et al. Effect of tipranavir-ritonavir on pharmacokinetics of raltegravir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2752–2755. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01486-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson MS, Sekar V, Tomaka F, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r) and raltegravir (RAL) in healthy subjects. Program and abstracts of the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Oct 2008; Washington DC, USA. Abstract A-962. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson MS, Kakuda TN, Hanley W, et al. Minimal pharmacokinetic interaction between the human immunodeficiency virus nonnucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor etravirine and the integrase inhibitor raltegravir in healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4228–4232. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00487-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]