Abstract

Contributions of fast (femtosecond) dynamic motion to barrier crossing at enzyme catalytic sites is in dispute. Human purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) forms a ribocation-like transition state in the phosphorolysis of purine nucleosides and fast protein motions have been proposed to participate in barrier crossing. In the present study, 13C-, 15N-, 2H-labeled human PNP (heavy PNP) was expressed, purified to homogeneity, and shown to exhibit a 9.9% increase in molecular mass relative to its unlabeled counterpart (light PNP). Kinetic isotope effects and steady-state kinetic parameters were indistinguishable for both enzymes, indicating that transition-state structure, equilibrium binding steps, and the rate of product release were not affected by increased protein mass. Single-turnover rate constants were slowed for heavy PNP, demonstrating reduced probability of chemical barrier crossing from enzyme-bound substrates to enzyme-bound products. In a second, independent method to probe barrier crossing, heavy PNP exhibited decreased forward commitment factors, also revealing mass-dependent decreased probability for barrier crossing. Increased atomic mass in human PNP alters bond vibrational modes on the femtosecond time scale and reduces on-enzyme chemical barrier crossing. This study demonstrates coupling of enzymatic bond vibrations on the femtosecond time scale to barrier crossing.

Keywords: femtosecond motions, kinetic isotope effect, transition state structure, enzymatic catalysis, protein dynamics

Dynamic motions in enzyme catalysis are composed of time scales ranging from milliseconds for protein conformational changes to femtoseconds for single bond vibrations. While the overall catalytic turnover rates for enzymes are commonly in the millisecond time scale, the lifetimes of enzymatic transition-state structures exist on the femtosecond time scale (1, 2). The role of protein dynamics has been brought into question with the suggestion that electrostatic preorganization is the sole force responsible for the catalytic prowess of enzymes (3). However, the idea that dynamics is involved in enzymatic catalysis is more widely accepted and is supported by theoretical and experimental work (4–6). The temporal similarity of catalysis and slow conformational changes has led to proposals that chemistry (crossing the transition-state barrier) is linked to millisecond motions of proteins (1, 7). Conversely, theoretical analyses have pointed to femtosecond promoting vibrations leading to chemical barrier crossing (8–10). Femtosecond time scale motions are challenging to probe by experimental approaches for enzyme reactions in solution. Here we report an approach to this problem by isotopic substitution of the enzyme.

Increased atomic mass to alter bond vibration frequencies is well established in chemistry, as isotope effects have long been employed to probe mechanism and transition-state geometry of reactions (11). Replacement of 12C, 14N, and nonexchangeable 1H in amino acid residues of an enzyme by 13C, 15N, and 2H, respectively, slows the femtosecond vibrational modes of these atoms, keeping electrostatic properties unaltered, according to the Born-Oppenheimer approximation (12, 13).

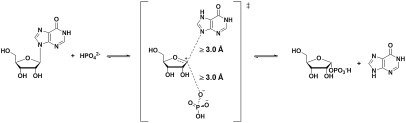

Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP)* (EC 2.4.2.1) catalyzes the reversible phosphorolysis of 6-oxypurine (2′-deoxy)-β-D-ribonucleosides to yield (2-deoxy)-α-D-ribose 1-phosphate and the purine base (14). Kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) and density functional theory calculations on the reaction catalyzed by human PNP support a fully dissociated transition-state structure, with formation of a ribocation (15) (Fig. 1). Experimental studies of this reaction have correlated protein dynamics with catalysis and computational studies support femtosecond time scale motions associated with transition-state formation (10, 16–21).

Fig. 1.

Reaction catalyzed by human PNP and the transition state as established from KIE studies (15).

In the present study, human PNP labeled with 13C, 15N, and nonexchangeable 2H (heavy PNP) was expressed and purified to homogeneity. Mass spectrometry confirmed the overall increase in mass of heavy PNP compared to natural isotope abundance enzyme (light PNP). The effect of altered femtosecond bond vibration frequencies in the enzyme on different portions of the catalytic cycle was investigated by steady-state kinetics, KIEs, forward commitment analysis, and pre-steady-state kinetics under single-turnover conditions. The results indicate that femtosecond motions are linked to chemical barrier crossing (9), a hypothesis we refer to as femtosecond dynamic coupling.

Results

Expression and Purification of Light and Heavy PNP.

Unlabeled and 13C-, 15N-, 2H--labeled human PNPs were expressed and purified to homogeneity (Fig. S1). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) analyses determined subunit masses of 32,161 Da and 35,350 Da for light and heavy PNP, respectively, confirming a 9.9% increase in mass (Fig. S2). Isotopic substitution in the enzyme is limited to nonexchangeable positions because solvent-exchangeable 2H are replaced by 1H during postexpression enzyme purification and storage in buffered normal water.

Steady-State Kinetics.

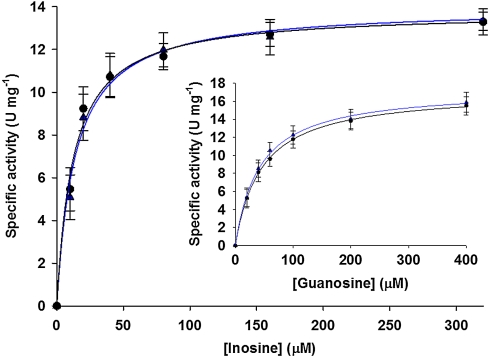

Light PNP and heavy PNP showed Henri-Michaelis-Menten kinetics with inosine (Fig. 2) or guanosine (Fig. 2, inset) as substrates in phosphorolysis reactions. Steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and KM) with inosine and guanosine were the same for light and heavy PNPs (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Steady-state saturation curves for inosine phosphorolysis catalyzed by light (blue) and heavy (black) PNPs. Inset displays steady-state saturation curves for guanosine phosphorolysis catalyzed by light (blue) and heavy (black) PNPs. Lines are data fits to Eq. 7.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for light and heavy PNPs

| Kinetic parameter | Light PNP | Heavy PNP | Difference* |

| Inosine | |||

| KM(μM)† | 13 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 | NS |

| kcat(s-1)† | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | NS |

| kchem(s-1)‡ | 69 ± 3 | 55 ± 2 | 14 ± 4 (20%) |

| Cf§ | 0.163 ± 0.010 | 0.139 ± 0.009 | 0.024 ± 0.013 (15%) |

| Guanosine | |||

| KM(μM)† | 42 ± 6 | 45 ± 8 | NS |

| kcat(s-1)† | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | NS |

| kchem(s-1)‡ | 26 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 7.0 ± 1.4 (27%) |

| Cf§ | 0.173 ± 0.013 | 0.122 ± 0.015 | 0.051 ± 0.020 (30%) |

*Percentage difference relative to light PNP is expressed in parentheses. NS: not significant, as determined by a t-test yielding p > 0.05.

†Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of duplicate measurements for phosphorolysis reactions.

‡Values represent mean ± standard error of at least twenty replicates in four independent experiments for phosphorolysis reactions.

§Dimensionless parameter. The values represent mean ± standard error of eight replicates in two independent experiments for arsenolysis reactions.

Isotope Effects and Forward Commitments.

Competitive KIEs for the arsenolysis of inosine were measured with heavy and light PNPs (Table 2). The use of arsenate instead of phosphate renders the overall reaction irreversible, decreases its kinetic complexity, and simplifies isotope effect analysis (22). Isotope effects on V/K were found to be identical, within experimental error, for light and heavy PNPs. Intrinsic isotope effects were obtained upon correction for forward commitment factors (Cf) using Eq. 1, where LV/K is the observed isotope effect on V/K and Lk is the intrinsic isotope effect (23).

| [1] |

Intrinsic isotope effects (Table 2) are also the same, within experimental error, for light and heavy PNPs. Intrinsic KIEs report on the bond vibrational status of the reactants at the transition state (24); therefore, natural abundance and mass-altered PNPs form the same transition states with bound reactants.

Table 2.

V/K and intrinsic KIEs for inosine arsenolysis by light and heavy PNPs

| KIE | Heavy/light inosines | KIE type | KIE for light PNP | KIE for heavy PNP | Difference |

| 1′-14C | 1′-14C vs. 4′-3H | V/K | 0.998 ± 0.004* | 0.995 ± 0.005* | 0.003 |

| Intrinsic | 0.998 ± 0.005 | 0.994 ± 0.006 | 0.004 | ||

| 9-15N | 5′-14C,9-15N vs. 4′-3H | V/K | 1.009 ± 0.004* | 1.006 ± 0.004* | 0.003 |

| intrinsic | 1.010 ± 0.005 | 1.007 ± 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| 1′-3H | 1′-3H vs. 5′-14C† | V/K | 1.167 ± 0.004 | 1.176 ± 0.002 | 0.009 |

| intrinsic | 1.194 ± 0.005 | 1.200 ± 0.003 | 0.006 | ||

| 2′-3H | 2′-3H vs. 5′-14C† | V/K | 1.056 ± 0.004 | 1.053 ± 0.002 | 0.003 |

| intrinsic | 1.065 ± 0.005 | 1.060 ± 0.003 | 0.005 | ||

|

vs. 5′-14C† vs. 5′-14C†

|

V/K | 1.054 ± 0.002 | 1.051 ± 0.004 | 0.003 |

| intrinsic | 1.063 ± 0.003 | 1.058 ± 0.005 | 0.005 | ||

| 4′-3H | 4′-3H vs. 5′-14C† | V/K | 1.007 ± 0.003 | 1.004 ± 0.004 | 0.003 |

| intrinsic | 1.008 ± 0.003 | 1.005 ± 0.004 | 0.003 |

*Experimental values corrected for remote 4′-3H KIE according to the equation KIE = KIEobs × 4′-3H KIE. KIE values represent mean ± standard error of six replicates in two independent experiments.

†The remote 5′-14C KIE is assumed to be unity.

The Cf values for inosine, estimated by the isotope-trapping method (25), are 0.163 ± 0.010 and 0.139 ± 0.009 for light and heavy PNPs, respectively, in the presence of arsenate to reduce reverse commitment. This change represents a 15% decrease in Cf for heavy PNP. Values of Cf were also estimated for the arsenolysis of guanosine, yielding 0.173 ± 0.013 and 0.122 ± 0.015 for light and heavy PNP respectively, a difference of 30% (Table 1). The Cf values represent the probability of barrier crossing relative to diffusional release of reactants, and indicate reduced barrier crossing efficiency in heavy PNP (see Discussion).

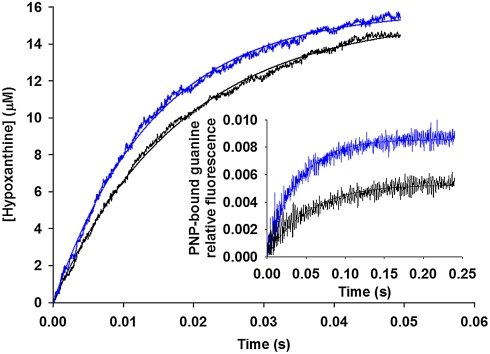

Single-Turnover Rate Constants.

Single-turnover rate constants were measured for light and heavy PNPs in phosphorolysis reactions with inosine (Fig. 3) and guanosine (Fig. 3, inset). Data fitting to a single exponential equation yielded values for observed single-turnover rate constants (kobs) with inosine of 69 ± 3 s-1 and 55 ± 2 s-1 for light and heavy PNPs, respectively, representing a 20% difference. Guanosine as substrate resulted in a kobs difference of 27%, as values of 26 ± 1 s-1 and 19 ± 1 s-1 were obtained, respectively, for light and heavy PNPs (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Representative stopped-flow average traces for single-turnover experiments for inosine phosphorolysis by light (blue) and heavy (black) PNPs. Inset shows representative stopped-flow average traces for single-turnover experiments for guanosine phosphorolysis by light (blue) and heavy (black) PNPs. Lines are data fits to a single-exponential equation.

Discussion

The increase in subunit mass of human PNP had no effect on steady-state kinetics of the enzyme, because both light and heavy PNPs followed Henri-Michaelis-Menten kinetics with superimposable saturation curves (Fig. 2). The values of KM for inosine and guanosine were unchanged with the heavy enzyme. As the KM value for PNP is dominated by substrate binding and release rates, the protein conformational changes involved in substrate binding and release are unaffected by altered protein mass. In the PNP reaction, kcat, the steady-state turnover number has been shown to be dominated by the rate of nucleobase release and not by the rate of the chemical step (21, 22, 26). Therefore, product release is unchanged by isotopic labeling of the PNP protein because kcat values are the same for both light and heavy enzymes. These observations indicate that femtosecond, mass-dependent dynamic events do not influence the steady-state kinetic parameters of the PNP reaction. Substrate binding and product release are linked to slow (nanosecond to millisecond) conformational changes (21) and these are apparently not influenced by mass-dependent femtosecond bond vibrational changes.

The ribocation-like transition state formed by human PNP (15) (Fig. 1) is reported to possess a lifetime of 10 femtoseconds (9, 10), a time scale similar to the bond vibrations that are altered by isotopic labeling of atomic nuclei (11). Intrinsic KIEs for labeled inosines as substrates for PNP reflect differences in bond vibrational environment between substrates in solution and at the transition state (24). Accordingly, KIE analysis has been used to probe transition-state structures of PNP as well as several related enzyme-catalyzed reactions (6, 27–30). The intrinsic KIEs of heavy and light PNP are indistinguishable within experimental error (Table 1), indicating that altered femtosecond protein dynamic motions do not change the geometry of the PNP transition state.

Even though substrate binding and product release is unchanged in heavy PNP, the probability of chemical barrier crossing for the Michaelis complexes is decreased in both forward commitment and single-turnover experiments. Forward commitment, Cf, is the probability of a substrate in the Michaelis complex to pass the chemical barrier relative to its probability of dissociation to free substrate (31). The lowered Cf for inosine and guanosine with heavy PNP reflects a decrease in the probability of on-enzyme barrier crossing. This analysis is also supported by the 20% and 27% decreases in single-turnover rate constants, kchem, for inosine and guanosine, respectively, with heavy PNP. These decreases correlate well with the respective 15% and 30% reductions in Cf for these substrates with heavy PNP. The kchem values with guanosine were measured under subsaturating conditions and thus may contain a contribution from substrate binding (32); however, because guanosine KM is the same for both enzymes, binding contributions should be unaltered, and the difference in kobs reflects differences on steps after formation of the respective Michaelis complexes.

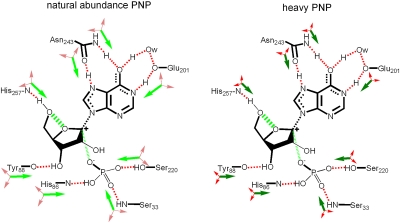

We attribute the heavy PNP effects to altered bond excursions in the enzyme-reactants complex (Michaelis complex) leading to altered probability of chemical transition-state barrier crossing (PNP: Pi: nucleoside↔PNP: R1P: nucleobase). The probability of barrier crossing is decreased with the heavy enzyme as indicated by the mass-altered vibrational modes of the amino acids contributing to chemistry (Fig. 4). The probability of the sum of the femtosecond dynamic motions in finding paths over the transition-state barrier is related to the probability with which all favorable enzyme-reactant interactions (green arrows in Fig. 4) are simultaneously optimized. Because of increased protein mass, the frequency of finding these barrier-crossing paths is decreased, slowing the rate as a function of mass.

Fig. 4.

Scheme indicating mass-altered bond vibrational modes in the catalytic site of heavy PNP. Increased protein atomic mass reduces the frequency of bond vibrations by extension of the relationship  where ν, k and μ are frequency, force constant and reduced mass, respectively. Likewise, the vibrational energy levels,

where ν, k and μ are frequency, force constant and reduced mass, respectively. Likewise, the vibrational energy levels,  , where E, n and h are energy, quantum number and Planck’s constant, respectively, are lowered by increased protein mass. The shorter arrows shown for heavy PNP illustrate the altered vibrational property. Green arrows promote barrier crossing and red arrows are orthogonal to the reaction coordinate. Heavy PNP has a reduced probability of reaching (and crossing) the transition state. The change is manifested in the experimentally observed decrease in rate of on-enzyme chemistry for heavy PNP. The diagram is modified from (45) and the amino acid contacts are from (46).

, where E, n and h are energy, quantum number and Planck’s constant, respectively, are lowered by increased protein mass. The shorter arrows shown for heavy PNP illustrate the altered vibrational property. Green arrows promote barrier crossing and red arrows are orthogonal to the reaction coordinate. Heavy PNP has a reduced probability of reaching (and crossing) the transition state. The change is manifested in the experimentally observed decrease in rate of on-enzyme chemistry for heavy PNP. The diagram is modified from (45) and the amino acid contacts are from (46).

By isotopic substitution, we increased the mass of PNP by 9.9% and altered the bond vibrational frequency without affecting electrostatic properties, according to the Born-Oppenheimer approximation (12). Isotopic substitution with 13C, 15N, and nonexchangeable 2H reduces the probability of chemical barrier crossing. Steady-state kinetic parameters related to binding and dissociation of substrates and release of the last product, and KIE values related to transition-state structure and geometry are unaffected. As isotopic labeling of PNP decreases the femtosecond vibrational frequencies of bonds involving atoms with increased mass, an interpretation of the data is that femtosecond motions of the enzyme are probabilistically linked to Michaelis complex excursions leading to barrier crossing, here dubbed femtosecond dynamic coupling. Enzyme motions on the femtosecond time scale are responsible for a probabilistic sampling of the Michaelis complex in search of the conformations that will lead to barrier crossing (8–10). Millisecond protein motions are not coupled to barrier crossing (33). The increase in PNP mass lowers the number of local dynamic conformations the enzyme can sample in a given time, consequently reducing the chance of finding the collective sum of optimized enzyme-reactant contacts to promote barrier crossing. Fast dynamic motions in proteins are an inevitable consequence of bond vibrational modes, and these motions have been experimentally observed in stable complexes of formate dehydrogenase with azide as a transition-state analogue (34, 35). However, a literature search revealed no other reports of mass-altered chemical efficiency in enzyme-catalyzed reactions.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

D-[1-3H]Ribose, D-[1-14C]ribose,  , D-[6-14C]glucose, and D-[5-3H]glucose were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. Deuterium oxide (99.9%),

, D-[6-14C]glucose, and D-[5-3H]glucose were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. Deuterium oxide (99.9%),  , and [15N] ammonium chloride were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Pyruvate kinase, myokinase, hexokinase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, glutamic acid dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconic acid dehydrogenase, adenosine deaminase, and phosphoriboisomerase were from Sigma-Aldrich. Alkaline phosphatase was from Roche. Ribokinase and phosphoribosyl-α-1-pyrophosphate synthetase were prepared as previously described (36, 37). Hypoxanthine-guanine phophoribosyltransferase was a kind gift from Keith Hazleton of this laboratory. All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercially available sources and were used without further purification.

, and [15N] ammonium chloride were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Pyruvate kinase, myokinase, hexokinase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, glutamic acid dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconic acid dehydrogenase, adenosine deaminase, and phosphoriboisomerase were from Sigma-Aldrich. Alkaline phosphatase was from Roche. Ribokinase and phosphoribosyl-α-1-pyrophosphate synthetase were prepared as previously described (36, 37). Hypoxanthine-guanine phophoribosyltransferase was a kind gift from Keith Hazleton of this laboratory. All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercially available sources and were used without further purification.

Expression and Purification of Human PNP.

Light PNP was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring a pCR-T7/CT-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) containing the codifying sequence for human PNP, as previously described (38). Heavy PNP was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS (Invitrogen) cells, containing the same construct. Cells were grown in M63 minimum medium supplemented with  and [15N]ammonium chloride, containing 100 mg mL-1 ampicillin, at 37 °C. All solutions for M63 preparation and supplementation were prepared in D2O. After an OD600 = 1.0 was reached, protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside. Cells were allowed to grow for additional 24 h and harvested by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 30 min. Both light and heavy PNPs were purified as previously published (39) using an AKTA FPLC system (GE) at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometricaly at 280 nm using the theoretical extinction coefficient of 30,160 M-1 cm-1 (http://expasy.org). Subunit molecular mass was determined by MALDI-TOF-MS.

and [15N]ammonium chloride, containing 100 mg mL-1 ampicillin, at 37 °C. All solutions for M63 preparation and supplementation were prepared in D2O. After an OD600 = 1.0 was reached, protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside. Cells were allowed to grow for additional 24 h and harvested by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 30 min. Both light and heavy PNPs were purified as previously published (39) using an AKTA FPLC system (GE) at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometricaly at 280 nm using the theoretical extinction coefficient of 30,160 M-1 cm-1 (http://expasy.org). Subunit molecular mass was determined by MALDI-TOF-MS.

Synthesis and Purification of Radiolabeled Inosines.

, [4′-3H]-, [5′-14C]-, [1′-3H]-, [5′-14C,9-15N]-, and [1′-14C]inosine were prepared as reported (40). [2′-3H] Inosine was prepared as described (41).

, [4′-3H]-, [5′-14C]-, [1′-3H]-, [5′-14C,9-15N]-, and [1′-14C]inosine were prepared as reported (40). [2′-3H] Inosine was prepared as described (41).

Measurement of Competitive Isotope Effects.

KIEs on V/K were measured for inosine arsenolysis by the competitive radiolabel method (37) at 25 °C. A typical reaction mixture contained in a 1-mL final volume 50 mM NaH2AsO4 (pH 7.5), 16 nM heavy or light HsPNP, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 250 μM inosine (3H-labeled, 14C-labeled, and cold carrier). Reactions were allowed to proceed to 25–35% completion as determined for a nonradioactive replicate reaction by hypoxanthine:inosine ratios measured by reversed-phase HPLC. From each reaction mixture, 300 μL were loaded onto each of three charcoal columns (150 mg Carbograph Extract-Clean columns, W. R. Grace & Co.). The remainder of each reaction mixture was completely converted to products by addition of 10 μM of light HsPNP. After complete reaction, 40 μL were loaded onto each of two charcoal columns. Ribose was eluted into scintillation vials by washing with 3 mL of 10 mM ribose in 10% ethanol. After removal of solvent by vacuum centrifugation, samples were dissolved in 200 μL of H2O, mixed with 10 mL of scintillation fluid (PerkinElmer), and counted for radioactivity in a Tricarb 2910 TR scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). A sample with only [14C]inosine was also counted as a standard.

Samples were counted in dual-channel fashion, with the 3H signal appearing only in channel 1, and the 14C signal, in both channels. The total 3H signal was assessed by Eq. 2, and the total 14C signal, by Eq. 3, in which 3H is the total number of cpm for this isotope, 14C is the total number of cpm for this isotope, channel 1 and channel 2 are the number of cpm in each channel, and r is the channel 1 to channel 2 ratio of 14C standard (37).

| [2] |

| [3] |

Experimental KIEs were calculated and extrapolated to 0% reaction using Eq. 4, where Rf and R0 are the ratios of heavy to light isotopes at partial and complete conversions, respectively, and f is the fraction of substrate conversion.

| [4] |

Determination of Forward Commitment Factor.

The forward commitments (Cf) for inosine and guanosine in the arsenolysis catalyzed by light and heavy PNPs were measured by the isotope-trapping method (25). Pulse incubation mixtures with inosine (20 μL) containing 20 μM light or heavy PNPs, 40 μM [1′-14C]inosine, and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, at 25 °C, were chased with a solution (480 μL) consisting of 2 mM inosine, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 50 mM NaH2AsO4. Pulse incubation mixtures with guanosine (20 μL) containing 25 μM light or heavy PNPs, 60 μM [1′-14C]guanosine, and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, at 25 °C, were chased with a solution (480 μL) consisting of 2 mM guanosine, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 50 mM NaH2AsO4. After 5 s, the reactions were quenched with 50 μL of 1 N HCl, and chromatographed in charcoal columns (1 g Carbograph Extract-Clean columns, W. R. Grace & Co.) and prepared for scintillation counting as described above for KIE measurements. Values obtained in the absence of arsenate were used as controls to correct the others. Cf was calculated according to Eq. 5, where Y is the ratio of moles of ribose to moles of enzyme-substrate complex. The concentration of enzyme-substrate complex was calculated with Eq. 6, in which ES is the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex, E is the total concentration of enzyme in the pulse, S is the total concentration of either inosine or guanosine in the pulse, and KM is the Michaelis constant for either inosine or guanosine.

| [5] |

| [6] |

Saturation Curves Under Steady-State Conditions.

Apparent steady-state parameters were determined by measuring initial rates as a function of either guanosine or inosine concentration at 25 °C. The decrease in absorbance at 258 nm upon conversion of guanosine to guanine (Δϵ = -5,500 M-1 cm-1) (42) was monitored in a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Varian). Guanosine phosphorolysis reactions contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM inorganic phosphate (Pi) pH 7.5, varying guanosine concentrations (20–400 μM), and 20 nM of either light or heavy HsPNP. The decrease in absorbance at 280 nm upon conversion of inosine to hypoxanthine (Δϵ = -1,000 M-1 cm-1) (43) was monitored in the same reaction conditions, except for varying inosine concentrations (10–320 μM). . Kinetic parameters were obtained upon data fitting to Eq. 7, where v is the initial velocity, V is the maximal velocity, S is the concentration of variable substrate, and KM is the Michaelis constant for the variable substrate.

| [7] |

Single-Turnover Rate Constants.

Single-turnover rate constants were determined by monitoring the increase in fluorescence upon formation of enzyme-bound guanine (44), or the decrease in absorption upon conversion of inosine to hypoxanthine in an SX-20 stopped-flow spectrofluorometer (Applied Photophysics) (dead time ≤ 1.25 ms) at 25 °C. For experiments with guanosine, the excitation wavelength was 280 nm with slit width of 0.5 mm, and fluorescence signal above 305 nm (with slit width of 2 mm) was selected using a WG305 Scott filter positioned between the photomultiplier and the sample cell. Fluorescence change was monitored for 240 ms, and 1,000 points were collected for each individual curve. Syringe 1 contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM Pi, pH 7.5, and either light or heavy HsPNP at 30 μM (15 μM chamber concentration), while syringe 2 contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM Pi, pH 7.5, and 10 μM guanosine (5 μM chamber concentration). Fluorescence change was normalized for background fluorescence. For experiments with inosine, the wavelength was 280 nm and both slit widths were 0.5 mm. Absorbance change was monitored for 49 ms, and 500 points were collected for each individual curve. Syringe 1 contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM Pi pH 7.5, and either light or heavy HsPNP at 100 μM (50 μM chamber concentration), while syringe 2 contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM Pi pH 7.5, and 50 μM inosine (25 μM chamber concentration). The concentration of hypoxanthine formed was calculated using Δϵ = 1,000 M-1 cm-1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Dr. Keith Hazleton for his assistance in expressing heavy PNP. We thank Professor Richard L. Schowen for helpful suggestions in preparing this work. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Program Project GM068036 and Research Grant GM41916 to V.L.S.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1114900108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hammes-Schiffer S, Benkovic SJ. Relating protein motion to catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:519–541. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagel ZD, Klinman JP. Update 1 of: tunneling and dynamics in enzymatic hydride transfer. Chem Rev. 2010;110:41–67. doi: 10.1021/cr1001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamerlin SC, Warshel A. At the dawn of the 21st century: Is dynamics the missing link for understanding enzyme catalysis? Proteins. 2010;78:1339–1375. doi: 10.1002/prot.22654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. A perspective on enzyme catalysis. Science. 2003;301:1196–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1085515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klinman JP. Enzyme dynamics: control of active-site compression. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;2:907–909. doi: 10.1038/nchem.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states, transition-state analogs, dynamics, thermodynamics, and lifetimes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:703–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammes-Schiffer S. Hydrogen tunneling and protein motion in enzyme reactions. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:93–100. doi: 10.1021/ar040199a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caratzoulas S, Mincer JS, Schwartz SD. Identification of a protein-promoting vibration in the reaction catalyzed by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3270–3276. doi: 10.1021/ja017146y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz SD, Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states and dynamic motion in barrier crossing. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:551–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saen-Oon S, Quaytman-Machleder S, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Atomic detail of chemical transformation at the transition state of an enzymatic reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16543–16548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigeleisen J, Mayer MG. Theoretical and experimental aspects of isotope effects in chemical kinetics. Adv Chem Phys. 1958;1:15–76. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Born M, Oppenheimer JR. On the quantum theory of molecules. Ann Phys-Berlin. 1927;389:457–484. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckhart C. The kinetic energy of polyatomic molecules. Phys Rev. 1935;46:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalckar HM. Differential spectrophotometry of purine compounds by means of specific enzymes; determination of hydroxypurine compounds. J Biol Chem. 1947;167:429–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL. Transition state analysis for human and Plasmodium falciparum purine nucleoside phosphorylases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1458–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi0359123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghanem M, Li L, Wing C, Schramm VL. Altered thermodynamics from remote mutations altering human toward bovine purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2559–2564. doi: 10.1021/bi702132e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo M, Li L, Schramm VL. Remote mutations alter transition-state structure of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2565–2576. doi: 10.1021/bi702133x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saen-Oon S, Ghanem M, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Remote mutations and active site dynamics correlate with catalytic properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biophys J. 2008;94:4078–4088. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saen-Oon S, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Transition path sampling study of the reaction catalyzed by purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Z Phys Chem Neue Fol. 2008;222:1359–1374. doi: 10.1524/zpch.2008.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschi JS, Arora K, Brooks CL, 3rd, Schramm VL. Conformational dynamics in human purine nucleoside phosphorylase with reactants and transition-state analogues. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:16263–16272. doi: 10.1021/jp108056s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghanem M, Zhadin N, Callender R, Schramm VL. Loop-tryptophan human purine nucleoside phosphorylase reveals submillisecond protein dynamics. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3658–3668. doi: 10.1021/bi802339c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Catalytic mechanism and transition-state analysis of the arsenolysis reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13212–13219. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northrop DB. Steady-state analysis of kinetic isotope effects in enzymic reactions. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2644–2651. doi: 10.1021/bi00683a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleland WW. The use of isotope effects to determine transition-state structure for enzymic reactions. Methods Enzymol. 1982;87:625–641. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose IA. The isotope trapping method: desorption rates of productive E.S complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1980;64:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)64004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Inosine hydrolysis, tight binding of the hypoxanthine intermediate, and third-the-sites reactivity. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5964–5973. doi: 10.1021/bi00141a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCann JA, Berti PJ. Transition-state analysis of the DNA repair enzyme MutY. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5789–5797. doi: 10.1021/ja711363s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cen Y, Sauve AA. Transition state of ADP-ribosylation of acetyllysine catalyzed by Archaeoglobus fulgidus Sir2 determined by kinetic isotope effects and computational approaches. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12286–12298. doi: 10.1021/ja910342d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roston D, Kohen A. Elusive transition state of alcohol dehydrogenase unveiled. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9572–9577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel MP, et al. Kinetic and chemical mechanisms of the fabG-encoded Streptococcus pneumoniae beta-ketoacyl-ACP reductase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16753–16765. doi: 10.1021/bi050947j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Northrop DB. The expression of isotope effects on enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:103–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson KA. Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. The Enzymes. 1992;20:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisilakov AV, Cao J, Kamerlin SC, Warshel S. Enzyme millisecond conformational dynamics do not catalyze the chemical step. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2009;106:17359–17364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909150106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandaria JN, Dutta S, Hill SE, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Fast enzyme dynamics at the active site of formate dehydrogenase. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:22–23. doi: 10.1021/ja077599o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandaria JN, et al. Characterizing the dynamics of functionally relevant complexes of formate dehydrogenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17974–17979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912190107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh V, Lee JE, Nunez S, Howell PL, Schramm VL. Transition state structure of 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase from Escherichia coli and its similarity to transition state analogues. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11647–11659. doi: 10.1021/bi050863a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parkin DW, Leung HB, Schramm VL. Synthesis of nucleotides with specific radiolabels in ribose. Primary 14C and secondary 3H kinetic isotope effects on acid-catalyzed glycosidic bond hydrolysis of AMP, dAMP, and inosine. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9411–9417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murkin AS, et al. Neighboring group participation in the transition state of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5038–5049. doi: 10.1021/bi700147b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva RG, et al. Cloning, overexpression, and purification of functional human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Protein Expres Purif. 2003;27:158–164. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva RG, Hirschi JS, Ghanem M, Murkin AS, Schramm VL. Arsenate and phosphate as nucleophiles at the transition states of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2701–2709. doi: 10.1021/bi200279s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L, Luo M, Ghanem M, Taylor EA, Schramm VL. Second-sphere amino acids contribute to transition-state structure in bovine purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2577–2583. doi: 10.1021/bi7021365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bzowska A, Kulikowska E, Shugar D. Properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) of mammalian and bacterial origin. Z Naturforsch C. 1990;45:59–70. doi: 10.1515/znc-1990-1-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parkin DW, Schramm VL. Binding modes for substrate and a proposed transition-state analogue of protozoan nucleoside hydrolase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13961–13966. doi: 10.1021/bi00042a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghanem M, et al. Tryptophan-free human PNP reveals catalytic site interactions. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3202–3215. doi: 10.1021/bi702491d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states: thermodynamics, dynamics and analogue design. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;443:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho M-C, et al. Four generations of transition-state analogues for human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4805–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913439107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.