Abstract

Background

With more than 90 published studies of pollination mechanisms, the palm family is one of the better studied tropical families of angiosperms. Understanding palm–pollinator interactions has implications for tropical silviculture, agroforestry and horticulture, as well as for our understanding of palm evolution and diversification. We review the rich literature on pollination mechanisms in palms that has appeared since the last review of palm pollination studies was published 25 years ago.

Scope and Conclusions

Visitors to palm inflorescences are attracted by rewards such as food, shelter and oviposition sites. The interaction between the palm and its visiting fauna represents a trade-off between the services provided by the potential pollinators and the antagonistic activities of other insect visitors. Evidence suggests that beetles constitute the most important group of pollinators in palms, followed by bees and flies. Occasional pollinators include mammals (e.g. bats and marsupials) and even crabs. Comparative studies of palm–pollinator interactions in closely related palm species document transitions in floral morphology, phenology and anatomy correlated with shifts in pollination vectors. Synecological studies show that asynchronous flowering and partitioning of pollinator guilds may be important regulators of gene flow between closely related sympatric taxa and potential drivers of speciation processes. Studies of larger plant–pollinator networks point out the importance of competition for pollinators between palms and other flowering plants and document how the insect communities in tropical forest canopies probably influence the reproductive success of palms. However, published studies have a strong geographical bias towards the South American region and a taxonomic bias towards the tribe Cocoseae. Future studies should try to correct this imbalance to provide a more representative picture of pollination mechanisms and their evolutionary implications across the entire family.

Keywords: Palm-pollinator interactions, cantharophily, mellitophily, myophily, co-evolutionary relationships, Arecaceae

INTRODUCTION

The palm family comprises about 2450 species distributed throughout the tropics with a few species ranging into subtropical regions. Species richness is highest in South America and the Malesian region, whereas continental Africa has only 65 species. Most palms inhabit forested areas but a few occur in savannas or even deserts. In particular, arborescent and scandent palms form a conspicuous landscape element that may have keystone importance for the dynamics and functioning of the ecosystem.

Until 25 years ago, the prevailing view in the scientific literature was that palms were mainly wind-pollinated. A review of pollination studies conducted on palms by Henderson (1986), however, showed that mainly insects are responsible for transferring pollen from anthers to stigma. Henderson concluded that three major pollination syndromes exist in palms: beetle pollination (cantharophily), bee pollination (mellitophily) and fly pollination (myophily).

Since Henderson's review was published, a considerable amount of new information has accumulated concerning palm pollination mechanisms. The large majority of studies have been autecological, focusing on one species on one particular study site. Typically, these studies consist of plant phenological observations (onset and duration of flowering at the population level, duration of staminate and pistillate anthesis relative to each other) and insect observations (identity and numbers of visiting insects, pollen loads). Controlled pollination experiments that test the relative importance of autogamy, geitonogamy and xenogamy have rarely been conducted. In later years, a number of studies have appeared that compare phenological and morphological features across transitions in pollination mechanisms between putative closely related taxonomic entities. Other studies have dealt with floral scent as a selective attractant to pollinators and a putative isolating mechanism. Palms have also been included in synecological studies that focus on much larger antagonistic or mutualistic community networks.

Here we conduct a review of the more than 60 studies published since 1986. We include only studies with a main emphasis on palm pollination. Anecdotal or circumstantial observations reported in papers with a different main focus have been disregarded because of the unclear scientific documentation.

FRAMEWORK OF PALM–POLLINATOR INTERACTIONS

The interactions between palms and their pollination vectors are often complex and vary both in space and in time. The physico-chemical framework as set by the palm inflorescence and the constituent flowers is quite stable throughout one species and for that reason it is often ascribed high diagnostic value. Inflorescence and flower traits are important drivers of pollinator assembly in all angiosperms. In the following, we will deal with phenomena in palms that are of putative importance for pollination mechanisms.

The inflorescence

Palm inflorescences are borne laterally on the stem and exposed at various heights, from near the ground in Calamus acanthophyllus (Evans et al., 2001) to more than 50 m above the ground in Ceroxylon quindiuense (Galeano and Bernal, 2010). The overall structure and phenology of the inflorescence play an important role in protecting vital parts against herbivores and at the same time in attracting pollinators. The young inflorescences are often protected by the leaf sheath, a prophyll and usually one to several sheathing peduncular bracts and rachis bracts. The mature inflorescences are either condensed or loose with widely separated flowers. They may be partly enveloped by bracts forming a ‘pollination chamber’ or they can be expanded with widely separate branches and flowers offering free access to all parts by a wide array of flying insects.

The age of the palm at the first flowering is variable between species. Some understorey palms such as the pleonanthic (iteroparous) species of Chamaedorea initiate flowering when they are only a few years old. Hapaxanthic (semelparous) species, by contrast, store energy in the stem that will be mobilized at the end of their life cycle to sustain a large system of inflorescences. This happens after 15–20 years in Arenga westerhoutii (Pongsattayapipat and Barfod, 2009), and after 8–17 years in Metroxylon sagu (Flach, 1997; 8–12 years in mineral soils and 15–17 years in peaty soils) or 45 years and upwards in Corypha utan (Tomlinson, 1990).

The flowers within one inflorescence often open in distinct sequences and variation in this trait may be associated with the pollination mechanism. Thus, Henderson (2002) suggested a possible correlation between basipetal maturation of the flowers/triads and beetle pollination on the one hand, and between acropetal maturation and bee, fly and wasp pollination on the other hand. However, exceptions occur such as in the basipetally flowering Licuala peltata, which is pollinated by trigonid bees and not by beetles (Barfod et al., 2003). Given the relatively small number of palm species studied in this respect, caution should be taken before drawing general conclusions.

Sexual expression

Sexual expression in palms is separated at five distinct spatial levels: within flowers (in-between floral organs), within flower clusters (in-between flowers), within inflorescences (in-between partial inflorescence), within palms (in-between inflorescences) and in-between palms. The complexity of sexual expression in palms only becomes clear when the separation of male and female function is considered in both space and time. Our knowledge is still somewhat limited with respect to the importance of sexual expression for the pollination mechanism. Henderson (1986, 2002) pointed to a possible correlation between protogyny and beetle pollination but again exceptions are known such as Oenocarpus bataua, which is protandrous but beetle-pollinated (García, 1988; Küchmeister et al., 1998). To test the universality of this idea it would be particularly rewarding to study pollination mechanisms within the subtribe Arecinae, as a number of shifts between protandry and protogyny have taken place within this group during its diversification (Loo et al., 2006).

Morphological differences between staminate and pistillate flowers probably constitute an important part of the palm–pollinator framework of interaction. The degree of reduction of non-functional sexual organs is highly variable and flowers may either be morphologically identical such as in certain Australian and New Guinean representatives of Livistona (Dowe, 2009), or strongly dimorphic such as in the tribe Phytelepheae (Barfod, 1991) and the species Nypa fruticans (Dransfield et al., 2008), where vestigial organs are strongly reduced or absent. In certain species of Chamaedorea the pistillode of the staminate flower is sizeable and probably plays an important secondary role for the interaction with the pollinating insects (Askgaard et al., 2008). In the pistillate inflorescences of most species of the subtribes Salacinae and Calaminae (both in subfamily Calamoideae) the female flowers are coupled with a sterile staminate flower.

Mating systems

Mating systems control the patterns of genetic transmission within and among populations. Self-pollination restricts gene migration through pollen flow, reducing the variation within a population and increasing the variation between populations. Out-crossing, on the other hand, promotes gene flow and reduces the likelihood of micro-geographical differentiation and population sub-structuring. Unfortunately, few controlled pollination experiments have been conducted in palms and little is in general known about their mating system and compatibility. There is no record of autogamy in the strict sense, namely fertilization within hermaphroditic flowers. Fruit-set resulting from transfer of pollen grains between unisexual flowers, within the same inflorescence (geitonogamy), as revealed by bagging experiments has been reported in Geonoma irena (Borchsenius, 1997), Serenoa repens (Carrington et al., 2003) and Cocothrinax argentata (Khorsand Rosa and Koptur, 2009). The results of controlled out-breeding experiments in palms vary from 11 % fruit-set in Geonoma irena (Borchsenius, 1997) to 61 % in Acrocomia aculeata (Scariot et al., 1991). In unbagged controls even higher fruit-sets have been recorded, such as 80 % in the hermaphroditic species Cocothrinax argentata (Khorsand Rosa and Koptur, 2009). Future work is necessary to reveal whether the variation recorded is a result of differences between species and thus an inherent feature of the pollination mechanism.

Floral protection

Although the pollinating insects are probably a strong determining factor in floral evolution and diversification, other insects may have a negative impact on reproductive success. They prey on or parasitize other pollinators or destroy vital tissues of the flower due to herbivory or oviposition. This means that the structural and chemical properties of the inflorescences and flowers serve not only to attract pollinators but also to deter herbivores. In six distantly related genera of palms, Uhl and Moore (1977) compared morphological, anatomical, chemical and other factors, which they considered important for the pollination mechanism. In species of Bactris where the outer layers of the petals of the unopened male flowers function as feeding tissues for the visiting beetle fauna, they demonstrated that vasculature may play an important role in the pollination mechanism. Anatomical sections of the flowers of Bactris major revealed how the staminate petals differ from the pistillate ones by being relatively fleshy and having a single row of bundles located near the inner surface. Uhl and Moore (1977) interpreted the function of the latter as a protection of the stamens. After pistillate anthesis, the male flowers open and quickly disperse their pollen grains. Another example of sophisticated palm–pollinator interaction is the mess-and-soil pollination mechanism of the tribe Phytelepheae. Thousands of insects, mainly beetles, visit the male and female inflorescences where they feed on the fleshy tissues and pollen grains, oviposite, predate on other insects and/or seek protection during the night (Barfod et al., 1987; Bernal and Ervik, 1996; Ervik, 1993; Ervik et al., 1999). Interestingly, the floral defences and insect rewards differ between closely related species, probably as a result of diverging selection pressures (Barfod et al., 1999). A study of staminate and pistillate flowers of 28 species of Chamaedorea revealed considerable variation within this dioecious genus regarding their floral protection (Askgaard et al., 2008). When ranked according to three putative protective, histological features, (a) sclerified tissue, (b) silica bodies and (c) raphide-containing ideoblasts, the species fell into three groups: (1) male and female flowers well protected (11 spp.), (2) female flowers well protected and male flowers less protected (12 spp.) and (3) male and female flowers both moderately protected (5 spp.). Three pollination ecological studies have been conducted on species in the first group: Chamaedorea pinnatifrons, C. radicalis and C. ernesti-augustii. The first two are primarily wind-pollinated (Listabarth, 1993a; Berry and Gorchov, 2004) whereas the third was reported to be insect-pollinated (Hodel, 1992; Morgan, 2007). Otero-Arnaiz and Oyama (2001) revealed wind as the primary pollinating agent in C. alternans, a species belonging to the second group. Thus it remains to be demonstrated whether wind-pollinated flowers in this genus are more heavily protected than insect-pollinated flowers.

Henderson and Rodrígues (1999) investigated the stamens of 250 palm species representing 145 genera and found raphide bundles in approx. half of these (75 genera). Seventeen genera comprised species either with or without raphide bundles. No apparent pattern emerged from the study. Zona (2004) examined the embryos of 148 palm taxa to reveal raphide-containing ideoblasts. They were rare or absent except in the tribes Caryoteae and Areceae where they had an occurrence rate of approx. 60 %. In Aphandra natalia, raphide-containing ideoblasts are found in epidermal layers of the pseudo-pedicels that could play a putative role in the pollination mechanism (Barfod et al., 1999). Rapid longitudinal expansion of the receptacle during late ontogeny ruptures the epidermal layers of the pseudo-pedicels, which leads to a release of raphide-containing ideoblasts, similar to pollen grains in size and shape (Barfod and Uhl, 2001). Whether this is a mechanism to deter pollen-eating insects needs to be demonstrated. Interestingly, Ervik et al. (1999) noticed that curculionid visitors belonging to the subfamily Baridinae are exceptional in being more numerous on the female inflorescences where they oviposit in the tepals. This group of weevils is strictly associated with Aphandra natalia and individuals can carry large amounts of conspecific pollen grains on their hairy legs.

Thermogenesis

Thermogenesis is found in cycads, three monocotyledonous families (Araceae, Arecaceae and Cyclanthaceae), five basal angiosperm families (Annonaceae, Aristolochiaceae, Nymphaeaceae, Magnoliaceae and Illiciaceae), and in only one eudicot family (Nelumbonaceae) (Thien et al., 2000). Ervik and Barfod (1999) reviewed the literature on thermogenesis in palms and listed 48 records of temperature elevation in flowers and inflorescences across all subfamilies but one: Calamoideae (subfamilies sensu Dransfield et al., 2008). The phenomenon appears to be particularly widespread within the tribes Cocoseae and Phytelephanteae, perhaps as a result of sampling bias. Of the palms in which thermogenesis has been reported, 32 were potentially beetle-pollinated. The pollination mechanisms of the remaining species were either unknown (15) or attributed to other vectors (one: Attalea colenda, bee- and wind-pollinated). The ecological implications of thermogenesis probably vary from palm to palm, the most important ones being: (1) promotion of pollen tube growth, (2) stimulation of pollinators to leave the inflorescence, (3) diffusion of floral scent and (4) heat as a growth-promoting factor for developing eggs and larvae.

VECTORS OF PALM POLLINATION

The visiting insect fauna of palm inflorescences varies in terms of both species richness and abundance. The Appendix gives the number of species and genera that are represented in the insect fauna observed to visit nine different palm species. The number of insects present in the inflorescence at any given time varies from fewer than ten in understorey palms such as Geonoma irena (Borchsenius, 1997) to more than 10 000 such as recorded by Barfod et al. (1987) in Phytelephas tenuicaulis. Beach (1984) estimated that 40 000–100 000 individual weevils arrived on a single inflorescence of Bactris gasipaes at the beginning of anthesis.

Table 1.

Numbers of visiting insect species and genera recorded for nine species of palms

| Palm species | Number of visiting insects (species/genera) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Phytelephas seemannii* | 26/13 | Bernal and Ervik (1996) |

| Aiphanes erinacea | 28/24 | Borchsenius (1993) |

| Geonoma irena | 7/7 | Borchsenius (1997) |

| Astrocaryum mexicanum† | 29/26 | Búrquez et al. (1987) |

| Sabal etonia | 30/29 | Zona (1987) |

| Cocothrinax argentata | 5/5 | Khorsand Rosa and Koptur (2009) |

| Hyospathe elegans | 60/approx. 30 | Listabarth (2001) |

| Licuala spinosa | 29/29 | Barfod et al. (2003) |

| Calamus rudentum | 12/3 | Bøgh (1996) |

* The staminate inflorescence in species of Phytelephas is visited by thousands of insects. Barfod et al. (1987) thus recorded 6000 stypyilinid beetles, 3500 curculionid beetles (Phyllotrox) and 100 Nitidulid beetles (Mystrops) in Phytelephas tenuicaulis.

† Not including two bird visitors.

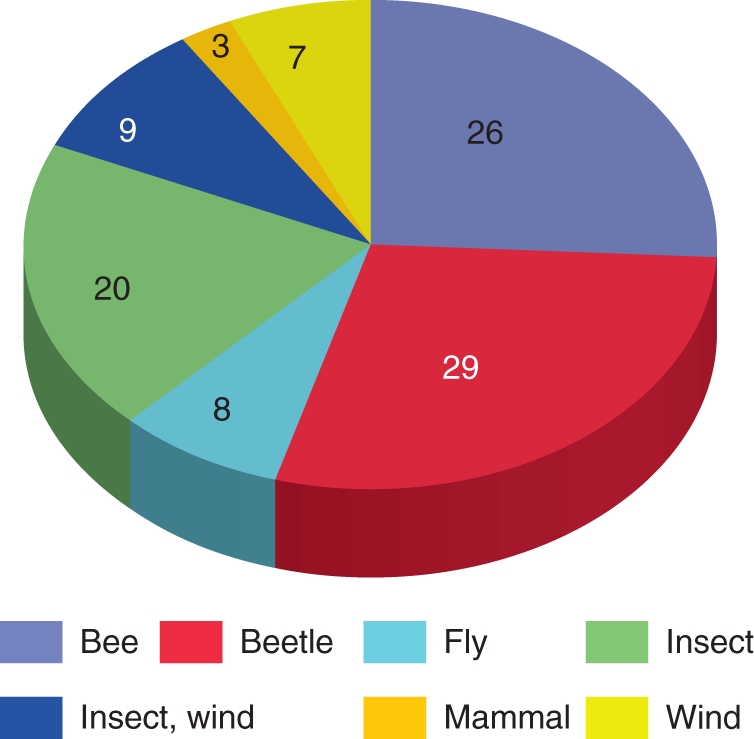

The new studies confirm the overall conclusion drawn by Henderson (1986) that palms are mainly insect-pollinated. Taking all this evidence into consideration, 29 % of all palm species studied have been referred to as beetle-pollinated, 26 % as bee-pollinated, 8 % as fly-pollinated, 7 % wind-pollinated and about 3 % as pollinated by mammals (Appendix). In 20 % of the species, several insect groups were emphasized as playing a role in pollination. Finally, in 9 % of the species both insects and wind were considered likely pollination vectors. Future studies of Asian palms will probably change this picture as large genera such as Calamus (approx. 374 spp.) and Daemonorops (approx. 101 spp.) may reveal a higher number of bee-pollinated species.

Fig. 1.

A breakdown of the 77 palm species listed in the Appendix according to inferred ‘most likely’ pollination vector (numbers in percentages). The groups ‘insect and wind’ and ‘insect’ cover species for which the conclusion on pollination mechanism was less specific.

New groups of visitors to palm inflorescences have also been recorded, such as Seba's short-tailed bat (Carollia perspicillata) and Commissaris' long-tongued bat (Glossophaga commissarisi) in Calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (Cunningham, 1995; Tschapka, 2003), pentailed treeshrew (Ptilocercus lowii) in Eugeissona tristis (Wiens et al., 2008), the Mexican mouse opossum (Marmosa mexicana) in Calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (Sperr et al., 2009) and even the nectar-eating grapsid crab (Armases cf. miersii) in Prestoea decurrens (Ervik and Bernal, 1996). The cited species are believed to play an important role in the pollination of the palm species on which they have been observed. Wind pollination has been demonstrated in two sympatric species of Howea, a genus endemic to the Lord Howe Islands (Savolainen et al., 2006). A novel pollination mechanism in palms was also recorded in Chamaedorea pinnatifrons by Listabarth (1993a). In this species dioecious thrips (Thysanoptera) and minute beetles of the family Ptiliidae (Coleoptera) enter the staminate flowers through small basal slits between the petals. Pollen grains released from the flowers are dispersed by the activities of the insects in small clouds. As the female flowers are rarely visited by the same insects as the male flowers, Listabarth concluded that pollen grains are transferred by wind and suggested the name ‘insect induced wind pollination’ for the mechanism. Mixed insect–wind pollination was also reported in Chamaedorea radicalis by Berry and Gorchov (2004) who found an increase in fruit-set from 3 % in bagged inflorescences to 23 % in palms in inflorescences that were treated to exclude insects, but allowing passage on wind-dispersed pollen grains from neighbouring individuals (bagging with nylon mesh, pore size approx. 1500 µm). This was little less than the 33 % fruit-set recorded in unbagged controls and reveals that this species is mainly wind-pollinated.

Beetle pollinators

The most common beetle visitors to palm flowers are the weevils (family Curculionidae), which constitute the largest family of living organisms on Earth with approx. 48 000 species. Weevils are plant eaters, usually with a narrow host range. The species visiting palm inflorescences are mostly nocturnal, they hide in the partly enveloping peduncular and rachis bracts during the day, and typically oviposit in the lightly protected parts of the inflorescence. Palm inflorescences are often visited by members of the tribe Derelomi (e.g. Phyllotrox, Derelomus). A detailed study on Elaeidobius kamerunicus, the main pollinator of the African oil palm, has revealed a large carrying capacity for pollen grains due to different types of setae (Dhileepan, 1992). Other weevils belonging to subfamilies such as Dryophthorinae (syn. Rhynchophorinae) and Baridinae use palms as hosts for their brood and are renowned as serious threats to palm health (Howard et al., 2001).

Another group of frequent visitors to palm inflorescences are the sap beetles (family Nitidulidae), which comprise about 3000 species. These beetles are typically attracted by decaying plant matter. Two genera are often recorded in palm inflorescences: Mystrops and Epurea. Both are frequent visitors to beetle-pollinated inflorescences and sometimes ascribed a major role in the pollination mechanism (e.g. Anderson et al., 1988 in Attalea phalerata; Barfod et al., 1987 in Phytelephas tenuicaulis; Kirejtshuk and Couturier, 2009 in Ceroxylon quindiuense [Karst.] H. Wendl.).

Scarabid beetles (family Scarabidae) are less frequent visitors to palm infloresences than the sap beetles. The group comprises more than 30 000 species that are renowned for their otherwise antagonistic role as borers of palms (Howard et al., 2001). The scarabid beetle Cyclocephala amazona is attracted to the inflorescences of Bactris gasipaes in cultivated populations in Costa Rica (Mora Urpí and Solis, 1980; Beach, 1984). During pistillate anthesis hundreds of scarabid beetles arrive on the inflorescences and feed on staminate flowers and specialized multicellular hairs on the peduncle and rachis. They remain on the inflorescence until a short burst of staminate anthesis the following day makes them leave in great numbers. Mora Urpí and Solis (1980) considered the scarabid beetles to be of only secondary importance for the pollination of Bactris gasipaes. Scarabid beetles in the genus Cyclocephala have also been reported to visit other cocosoid palm species in genera such as Astrocaryum and Acrocomia but their role in transferring pollen grains seems to be limited (Scariot et al., 1991; Listabarth, 1992).

The rove beetles (family Staphylinidae) is another mega-diverse beetle family found in palm inflorescences. The family comprises an estimated 46 000 species classified in 3200 genera. Most rove beetles prey on other invertebrates. Sometimes, they are found in great numbers in palm inflorescences, but their role as pollinators is usually judged as minor, due to their moderate pollen-carrying capacity. In complete contrast, Bernal and Ervik (1996) showed that staphylinid beetles belonging to the subfamily Aleocharinae were the main pollinator of Phytelephas seemanni. This is particularly interesting as members of Gyrophaenina, another subtribe of the same subfamily, breed in a similar way in the hymenium of fleshy mushrooms (Ashe, 1984, 1987).

Bee and fly pollinators

Another very important group of pollinators of palms are bees (superfamily Apoidea), with a total number of described species of about 18 000. Bees appear to attain their greatest abundance and species richnes not in the tropics, but in various warm-temperate, xeric regions (Michener, 2007). In the tropics, eusocial groups such as honey-bees (Apis spp.) and stingless bees (tribe Meliponini) are especially dominant. As bees generally feed themselves and their offspring exclusively with nectar and pollen, they are well-adapted, frequent and continuous flower visitors. Two particular familes play a major role in the pollination of palms: the sweat bees (familiy Halictidae) and the stingless bees (tribe Meliponini). Honey-bees of the genus Apis have been recorded as potential pollinators in a few cases such as Serenoa repens (Carrington et al., 2003) and in cultivated palms such as Cocos nucifera (da Conceição et al., 2004; Meléndez-Ramírez et al., 2004).

The sweat bees or halictid bees comprise about 2000 species that are mostly primitively eusocial and typically nest underground. The stingless bees are almost exclusively eusocial and their colonies can be found in decaying wood, rock crevices and in the soil (Michener, 2007). Representatives of the genus Trigona in particuler are found on palms. Both groups of bees are generalist pollen and nectar feeders that are attracted to flowers and inflorecences mainly by visual cues. They have baskets (corbiculae) on their hindlegs that enable them to collect pollen for the mass-provision of their brood. Bee-pollinated palm species in general are dependent on the presence of bee nests close by to ensure reproductive success. Their inflorescences are often located in the canopy or sub-canopy of the rain forest, such as in Calamus, Ptychosperma, Euterpe and Prestoea.

Certain groups of flies such as fruit flies are omnipresent on palm inflorescences. They are, however, generalist visitors to all kinds of flowers and probably of little consequence for pollination in palms, except perhaps in the case of Geonoma cuneata var. sodiroi in which Borchsenius (1997) suggested that drosophilid flies are the primary pollinator. Hover flies of the genus Copestylum have been reported as the main pollinator in two cases: Aiphanes erinacea (Borchsenius, 1993) and Prestoea schultzeana (Ervik and Feil, 1997). In addition, three families of flies have been reported as potential pollinators of palms (Borchsenius, 1997; Listabarth, 2001; Barfod et al., 2003): blow flies (family Caliphoridae), tachinid flies (family Tachinidae) and signal flies (family Plastytomatidae). Blow flies are attracted by strongly scented flowers and use nectar as a source of carbohydrates to fuel flight. Tachinid flies constitute a highly diverse group comprising an estimated 10 000 species. Although the adults are normally pollen and nectar feeders, the larvae of many species are parasitoids. Finally, the signal flies are often attracted to flowers and decaying fruit. In palm flowers they often probe for nectar. The larvae are phytophagous or saprofagous.

FLORAL REWARDS

Autecological studies of pollination mechanisms in palms have provided new insights into the rewards offered to the visiting insects. Rewards can be either nutritional (pollen grains, food tissues and nectar), oviposition sites or shelter. Most of the insect visitors to palm inflorescences are attracted by nutritional rewards. This applies to beetles, to some flies that feed on pollen grains and flower tissues (Uhl and Moore, 1977), and also to flies and bees that probe for nectar. Eusocial bees collect pollen grains in ‘baskets’ on their hind legs and transport them back to their hive to feed the groom. They are attracted to inflorescences by visual cues and are able to detect and remember minor morphological differences between male and female flowers. In the case of sexually dimorphic flowers, some bees will only visit the staminate flowers to collect pollen, and thus interact with the palm in an antagonistic way. In the pistillate inflorescences of species of the dioecious subtribes Salacinae and Calminae, female flowers and sterile staminate flowers are coupled such that the dimorphism between male and female inflorescences is disguised (Bøgh, 1996). Some palms such as Licuala peltata often produce copious amounts of nectar to attract bees in competition with other bee-pollinated plants (Barfod et al., 2003).

Sites for oviposition constitute another important reward for insect visitors to palm inflorescences. Boreholes of beetles in particular are often found in the inflorescences of palms during and after anthesis such as in Salacca (Mogea, 1978), Phytelephas (Ervik and Bernal, 1996) and Bactris (Listabarth, 1996). The beetles oviposit in fleshy tissues that are poor in sclerenchyma, tannin-rich cells and raphide-containing ideoblasts. In this way the larvae are surrounded by their food resource when they hatch. In members of the tribe Phytelepheae the short-lived male inflorescences are 10–20 °C warmer during anthesis than ambient temperature and are densely perforated by insect boreholes. Anthesis usually lasts less than 12 h and the inflorescence starts decaying soon after. Staphylinid and curculionid beetles that oviposit in the inflorescence complete their life cycle in less than a week, which is probably possible due to the elevated temperature.

The prophyll and various types of bracts that typically envelop palm inflorescences offer shelter, especially for nocturnally active beetles such as weevils and nitidulids. Hoppe (2005) observed one particular species of weevil to hide in great numbers underneath the large leathery bracts of the mangrove palm Nypa fruticans. The beetle was considered to be among the potential pollinators. Silberbauer-Gottsberger et al. (2001) suggested that the function of the enveloping bracts in palms and Cyclanthaceae is similar to that of the pollen chamber in cantharophilous members of Annonaceae formed by the thick fleshy petals and the ‘kettle’ in Araceae formed by the spathe. Whether the inflorescence bracts of palms offer shelter in combination with other rewards such as nutrition or brood site is unknown.

PALM–POLLINATOR EVOLUTIONARY RELATIONSHIPS

Ollerton et al. (2009) tested the idea that suites of phenotypic traits reflect convergent adaptations of flowers for pollination by specific pollen vectors in 482 angiosperms from Africa, North America and South America. Ordination of flowers in multivariate phenetic space showed that very few species fell within a discrete cluster and they therefore suggest caution when using ‘pollination syndromes’ to interpret floral diversification in general. No studies have been published that directly address the question of specificity of the visiting insects to palms. The role of potential pollinators in driving the co-evolutionary relationship is therefore a relatively open question. Henderson (2002) observed a high level of morphological co-variation between stem diameter and inflorescence size in beetle-pollinated palms, which he tried to explain by two operating factors: growth rate changes and pollination mechanisms. He regarded the significant correlation between stem diameter and inflorescence size, for example in Oenocarpus, as a result of selection pressures from taxonomically restricted groups of beetles that share similar and narrow feeding guilds. Conversely, he considered the lack of correlation seen in the mentioned traits in Prestoea to be a consequence of the looser framework of interaction between the palm and its diverse pollinator community of bees, flies and wasps. Henderson also observed that beetle-pollinated inflorescences tend to be condensed, unisexual and covered with bracts at anthesis, whereas bee-, fly- and wasp-pollinated palm flowers are elongate, often bisexual and free from bracts at anthesis. The fact that we can recognize such suites of co-occurring attributes in flowers and inflorescences that are referred to as ‘pollination systems’ shows that groups such as beetles, bees and flies are important drivers of co-evolutionary relationships. We recommend, however, that terms such as ‘syndrome’ and ‘pollination system’ be used cautiously as they invoke a somewhat simplified image of pollination mechanisms and bias our methodological approaches. Future studies that integrate both population genetics and phylogenetic approaches will undoubtedly reveal pollination mechanisms to be the result of complex biotic interactions through space and time.

A number of pollination mechanisms in palms have provided direct or indirect evidence for an open framework of interaction, which combines floral attributes of both beetle- and bee-pollinated species. This applies to Allagoptera arenaria and Syagrus inajai, which have both been described as being mainly beetle-pollinated (Leite, 1990; Küchmeister et al., 1997). Listabarth (2001) made observations on visitation rates to the flowers of Hyospathe elegans and suggested a mixed species feeding guild, which may be widespread in bee- and fly-pollinated palms. Apparent discrepancies in pollination mechanism reported from different studies could be a sign of open frameworks of interaction and low specialization of the potential pollinating insects. This applies to Attalea colenda (Balslev and Henderson, 1987 [beetles]; Feil, 1992 [bees]), Mauritia flexuosa (Storti, 1993 [nitidulid and curculionid beetles]; Ervik, 1993 [chrysomilid beetles]) and Iriartella setigera (Küchmeister et al., 1997 [Phyllotrox, Curculionidae]; Listabarth, 1999 [bees]). It should also be noticed that even though some pollinating agents only play a limited role in some areas, they could attain a major role especially under marginal conditions. Barfod et al. (2003) recorded large differences in the composition of the visiting fauna to inflorescences of Licuala spinosa across a local habitat gradient in Peninsular Thailand. The inflorescences of palms growing in forest subcanopies were visited by 18 insect species of which a calliphorid fly, a tachinid fly and a halictid bee carried the largest pollen loads. Palms growing in nearby, open Malaleuca cajuputi parkland were visited by five kinds of insects of which only two species of calliphorid flies carried large pollen loads.

Despite the evidence for an unspecialized pollination mechanism in the palms cited above, a few well-documented cases exist that suggest a specialized mutualistic palm–pollinator relationship. Anstett (1999) and Dufay (2010) demonstrated a nursery-deceit pollination mechanism in Chamaerops humilis in the Catalonia region of Spain. The main weevil pollinator, Derelomus chamaeropsis, depends completely on the palm to complete its life cycle. It oviposits in both male and female flowers, but larval development is suppressed in the pistillate flowers that end up producing fruits (Anstett, 1999). Another example is the transplanting of the African Oil Palm to South-East Asia, which can be viewed as a large-scale pollination experiment. Average fruit-set improved considerably from 52 to 71 % only after the introduction in the early 1980s of the ‘million dollar’ beetle Elaedobius kamarunicus from Africa (Syed, 1979; Basri, 1984). This clearly shows that some palms are highly dependent on the pollination services of just a single species of insect. Anderson et al. (1988) noted that the most likely pollinator of Attalea phalerata, the nitidulid beetle Mystrops mexicana, was observed in palm populations up to approx. 600 km apart, which indicates a widespread association. The question remaining is whether co-evolutionary relationships between the palm and its pollinators may be a driving force in diversification.

Sannier et al. (2009) tested the statistical significance of an association between pollen ornamentation and pollination mechanism in palms, taking phylogenetic relationships into account. Data on the most likely pollinators were extracted from the scientific literature. The authors did not detect any correlation between the two, nor did they find support for an ancestral pollination mechanism in the family. They showed that the results obtained were highly sensitive to the choice of character optimization algorithm used. Evidently such an analysis is susceptible to artefacts associated with limited sample size as well as geographical and taxonomic bias.

Barfod et al. (2010) optimized characters on a dated phylogeny of the tribe Phytelepheae and revealed within this topology an uneven distribution of unambiguous transformations of characters in the floral, pollination ecology and vegetative subsets. The relative number of characters from each subset that changed on a given branch deviated from a neutral prediction of a proportionate rate of character transformation. Interestingly, both of the splits in the phylogeny leading to new genera were accompanied by a disproportionately large change in floral morphological characters. This indicates that pollination mechanisms may be drivers of diversification in Phytelepheae and palms in general. Most probably, different insect visitors to the same palm display a whole range of specificities due to the open framework of interaction.

TRANSITIONS IN POLLINATION MECHANISMS

Studies that compare contrasting pollination mechanisms of closely related palm species are still few relative to the number of autecological studies. Borchsenius (1993) studied three species of Aiphanes along an elevation gradient in the Ecuadorean Andes and revealed a transition in phenology and floral morphology with increasing duration of male anthesis and decreasing P/O ratios towards higher elevation. This transition is reminiscent of the altitude-dependent increase in flower longevity found in other groups of flowering plants, such as Melastomataceae (Renner, 1989) and Monimiaceae (Feil, 1992) and it probably reflects changes in density, composition and foraging energetics of the insect fauna with increasing elevation. Changes in flower biology were accompanied by a shift in pollination mode from bee pollination in the lowland species Aiphanes eggersii, to fly pollination in the mid-altitude species A. erinacea, and pollination by gnats and midges in the montane forest species A. chiribogensis.

Barfod et al. (2003) demonstrated how a number of phenological, anatomical and morphological attributes reflect a transition in pollination mechanism from fly pollination to bee pollination in the genus Licuala. The fly-pollinated L. spinosa (subgenus Eulicuala) has relatively small, narrowly opened flowers that produce moderate amounts of nectar. In this species the opening of the flowers is scattered along the rachillae. In contrast, the two bee-pollinated species L. peltata and L. distans (subgenus Libericula) have large, widely opened flowers that produce copious amounts of nectar. In both species the flowering proceeded in short-lasting, basipetal pulses along the rachillae. The difference in nectar production amongst these species is coupled to anatomical differences in the flowers. Stauffer et al. (2009) found labyrinthine nectaries in L. peltata. Owing to undulations and convolutions of the secretory tissues, these nectaries continuously produce large amounts of nectar, making the flowers attractive to insects with high energy requirements, such as bees.

Núñez-Avellaneda et al. (2005) studied the relationship between floral phenology, pollinator behaviour and rainfall patterns in two palm species, Attalea allenii and Wettinia quinaria, in the Choco region of Colombia. They concluded that the diurnal anthesis in these species and the corresponding diurnal activity of their nitidulid pollinators (Mystrops spp.) have co-evolved as a response to predominantly high nocturnal rainfalls. Other Mystrops-pollinated palm species that are distributed in areas with less precipitation and diurnal rainfall patterns are characterized by being mainly pollinated at night.

Borchsenius (1997) studied the pollination mechanism in two sympatric understorey species of Geonoma in a seasonal lowland rainforest in western Ecuador. One species, G. irena, is pollinated mainly by meliponid and halictid bees. The other species, G. cuneata var. sodiroi, is most likely pollinated by drosophilid and sphaerocerid flies. Structural and phenological differences in the floral parts of the two species match the specific behaviour of the pollinators in a way similar to the fly-to-bee pollination transition described above in Licuala. In G. irena, flowering occurs in three overlapping pulses lasting 11–14 weeks in total. The male flowers have straight stamens through anthesis and emit a faint, somewhat metallic scent. In G. cuneata var. sodiroi, the flowering of a single inflorescence lasted for less than 1 week and the opening of the flowers did not follow any evident pattern. The male flowers have recurved stamens throughout anthesis, suitable for depositing pollen on small insects moving around between the flowers, and emit a pungent smell reminiscent of decaying plant matter. The main visitors to these flowers were drosophilid flies. The abscission of male flowers after 1–2 h of anthesis in the early morning was hypothesized to promote movement of these flies between inflorescences in male and female phases.

Morgan (2007) compared the pollination mechanisms of four sympatric species of Chamaedorea growing in seasonal to semi-evergreen forests in Belize (C. ernestii-augustii, C. oblongata, C. neurochlamys and C. tepejilote). Phenology was ruled out as an isolating mechanism as the four palms flowered relatively synchronously. All four species were apparently pollinated by the same species of thrips, Brooksothrips chamaedoreae. Wind was only considered of secondary importance as a pollen vector. It is therefore assumed that an unknown mechanism, such as a sterility barrier or incompatibility system, is responsible for maintaining reproductive isolation.

The results yielded by the numerous comparative studies cited above have provided further insights into the highly complex and dynamic co-evolutionary relationship between the palms and their pollinating agents. It will be particularly interesting to interpret the results obtained from comparative studies of closely related species assemblages within a phylogenetic framework.

FLORAL SCENT

A group of comparative studies in palms have dealt with floral scent as a selective attractant to pollinators and as the basis of a putative isolating mechanism. Based on a study of 14 Neotropical palm species, Knudsen et al. (2001) concluded that the scent of cantharophilous species was characterized by large amounts of one or a few dominant compounds, which probably reflects the fact that beetles rely heavily on scent cues in their search for food. Conversely, the scent of myophilous and melittophilous palms was found to contain a mixture of numerous compounds in smaller total amounts, indicating that scent is probably less important than visual cues. Azuma et al. (2002) included Nypa fruticans in a general study of floral scents emitted by mangrove plant species and revealed a high content of four different carotenoid derivaties that are known to attract insects. Among these were a beta-ionone which is highly attractive to certain beetles (Donaldson et al., 1990). Meekijjaroenroj et al. (2007) analysed the flower scent composition of four Licuala species. Although the chemical composition of flower scents was characteristic for each species, a principal components analysis ordination of species in scent component space failed to recover the currently accepted subgeneric classification. Studies of Geonoma macrostachys var. macrostachys at two spatial scales suggest that local differentiation in flower scent composition may constitute an isolating mechanism that could lead to sympatric speciation (Knudsen, 2002). Ervik et al. (1999) conducted a comparative study of floral scent chemistry and pollination ecology within the tribe Phytelepheae. They showed that not only do the active compounds attracting the pollinators differ between the three genera, but also that they are synthesized along separate pathways. Thus, the flower scent of Aphandra was dominated by a pyrazine (2-methoxy-sec-3-butylpyrazine), Ammandra emitted a range of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, whereas the main scent component in Phytelephas was p-methyl anisol (1-methoxy-4-methyl benzene) in extremely large amounts. Pyrazines similar to the one emitted by Aphandra natalia have been considered a defensive odour in other plants (Moore et al., 1990). At the peak of flowering, the estimated release from one inflorescence was 7 mg h−1, which is an order of magnitude higher than in other heavily scented plants such as in the moth-pollinated Brugmansia suaveolens, which releases up to 37 µg h−1 (Knudsen and Tollsten, 1993). Volatile compounds produced by the entire leaf in Chamaerops humilis attract pollinators only during flowering according to Dufay et al. (2004) and Caissard et al. (2004).

STAGGERED FLOWERING

A number of studies have looked into the role of staggered flowering in maintaining reproductive barriers or dividing pollinator resources among sympatric palm species. De Steven (1987) conducted observations on reproductive phenology over a 4-year period in a palm assemblage in Panama and discovered substantial variation. In most species 50 % or more of the individuals flowered each year whereas in clonal species of Bactris 30 % or fewer individual stems (ramets) flowered. In several species she detected highly asynchronous flowering within populations. Interestingly, fruiting was more synchronous than flowering, which was partly explained as a failure of the inflorescences flowering at certain times to produce mature fruits. The data also showed how strongly annual climatic variations can influence the reproductive behaviour of palms. Bøgh (1996) studied the reproductive phenology and pollination mechanisms of four sympatric species of Calamus in Peninsular Thailand (C. rudentum, C. longisetus, C. bousigonii and C. perigrinus). Flowering of the four species peaked in different months: C. rudentum in July, C. longisetus in December, C. bousigonii in November–December and C. perigrinus in February.

Listabarth (1996) also demonstrated staggered flowering in an assemblage of four cantharophilous species of palms in Amazonian Peru comprising two species of Bactris (B. bifida and B. monticola) and two species of Desmoncus (D. polyacanthos and D. mitis). In all four species, weevils (Phyllotrox spp.) and sap beetles (Epurea spp.) that oviposit in the inflorescences were demonstrated to be the most likely pollinators. Spatial distribution at the population level and phenological patterns revealed differing life strategies among the species, with the aforementioned factors showing some degree of inter-dependency. Henderson et al. (2000a, b) surveyed the phenological patterns and pollination mechanisms of ten sympatric species of Bactris in fragments of lowland Amazonian forest near Manaus, Brazil. The most common visitors were weevils (Phyllotrox spp.) and sap beetles (Colopterus spp.), but many other insects were also present such as rove beetles (Staphylinidae), scarab beetles (Scarabaeidae) and bees. The flowering phenologies of eight species were followed over more than three years. Anthesis occurred during the rainy season and early dry season and while temporal separation was evident, there were noticeable overlaps in the timing of flowering. Henderson et al. (2000a, b) noticed that the framework of palm–pollinator interaction as well as the fauna of visiting insects was quite different for each taxon. They concluded that the extended flowering of species of Bactris over at least 10 months had implications for the continuous supply of palm inflorescences available to the principal pollinators such as Phyllotrox.

Borchsenius (2002) compared the flowering of four sympatric varieties of the understorey palm Geonoma cuneata in Ecuador. The phenological histograms for each variety clearly revealed asynchronous flowering, which suggests that staggered flowering is probably an important mechanisms for limiting gene flow between closely related sympatric taxa and a potential driver of speciation processes. Besides the temporal separation of flowering, no major differences in the flowering biology of the four varieties were detected. Listabarth (1993b) similarly found differences in flowering season, flowering time and insect visitors of sympatric populations of Geonoma macrostachys var. macrostachys and G. macrostachys var. acaulis in Amazonian Peru.

PALM POLLINATION AND COMMUNITY NETWORK STUDIES

The interactions between plants and their pollinators form part of much larger antagonistic or mutualistic community networks (Bascompte and Jordano, 2007), characterized by great complexity and spatio-temporal variation, particularly in species-rich tropical ecosystems. Community-wide approaches are fundamental tools to describe the structure of communities, interactions of species complexes (Memmott, 1999), resilience against invasive species, environmental fluctuations or climate change (Aizen et al., 2008; Hegland et al., 2009; Padron et al., 2009) and the evolution of mutualisms (Memmott, 1999). Plant–pollinator networks are characterized by being heterogeneous (most species have a few interactions, while a few species are much more connected than expected by chance), nested (specialists interact with subsets of the species with which generalists interact) and built on weak and asymmetrical links among species. Only a handful of papers have been published that deal with the role of palms in a community network context.

Kitching et al. (2007) studied visitor assemblages at flowers in a tropical rain forest canopy in north Queensland. Three basic research questions were addressed relating to the composition of the visiting arthropod fauna, (1) between flowering and non-flowering canopy plants, (2) between tree species and (3) between different times of the year. Among the 79 plant species compared there were three palms: Calamus radicalis, Licuala ramsayi and Normanbya normanbyi. Significant seasonal differences in visitation were detected in N. normanbyi and C. radicalis. An association with thrips, flies and weevils existed in the former species and with mainly flies in the latter species. In N. normanbyi the differences between abundance levels at different sampling times were significant, indicating a more open framework of interaction. The authors suggested that the resource offered by the two palm species was sufficiently general to attract a wide range of visitors even when the background frequencies of particular insect taxa had changed.

Kimmel et al. (2010) conducted a study of pollination and seed dispersal modes in a 12-year-old secondary forest attached to the Atlantic forest of north-eastern Brazil. Among the 61 woody species encountered were three palms: Acrocomia intumescens, Desmoncus sp. and Elaeis guineensis (cultivated African oil palm). All are beetle-pollinated and considered as pioneers in this specific habitat. The prevalence of cantharophilous species in the subcanopy has been explained by the uneven vertical distribution of species associated with secondary forest vegetation (Begon et al., 1996).

van Dulmen (2001) compared pollination mechanisms and floral phenology in the canopies of a seasonally inundated forest and an upland rainforest in Amazonian Colombia. Four species of palms were included in the study: Astrocaryum aculeatum, Desmoncus polyacanthos, Euterpe precatoria and Iriartea deltoidea. They found that bees were among the most common pollinators in both forest types whereas other pollinators such as hummingbirds, bats, moths and beetles were much less common. Although differences in species composition between the two forest types did not influence phenological patterns, pollination systems and breeding systems overall, associations were observed between pollination mechanisms and certain plant taxa.

A few case studies have documented the effect of habitat fragmentation on pollination mechanisms. Anderson et al. (1988) studied the variation in pollination ecology of Attalea phalerata in Maranhão (Brazil) and showed that wind pollination played a more important role in open sites such as pastures. In Astrocaryum mexicanum Aguirre and Dirzo (2008) found that pollinator abundance was negatively affected by forest fragmentation with a 4·2-fold average difference between small and large fragments. Fruit-set, however, was not affected, which they explained by the relatively high number of pollinators and high abundance of palms in the small fragments.

Studies of plant–pollinator networks are still in their infancy, especially in the wet tropics where the complexity is often overwhelming. Further investigations of the role of palms within these networks will undoubtedly contribute new and exciting insights into the selective forces that drive the palm–pollinator co-evolutionary relationships.

CONCLUSIONS

More than 60 studies of pollination mechanisms in palms have been published since Henderson's (1986) review on palm pollination. They have provided new insights into autecological, comparative and synecological aspects of palm–pollinator interactions. Still only about 3 % of all palm species have been studied in detail with respect to their pollination mechanism. Therefore, caution should be exercised when making generalizations across the family.

The wealth of new studies has shown that the visiting fauna to palm inflorescences is even more diverse than that described by Henderson (1986). Spectacular new groups have been added to the list of visitors to palm inflorescences such as mammals (bats, pentailed treeshrew and Mexican mouse oppossum) and even a decapod crustacean species (grapsid crab). The bulk of palm species are, however, pollinated by insects and in particular beetles, bees and flies. The number of insect visitors per species varies from a few to tens of thousands. A few palms have been confirmed to be wind-pollinated. Insect-mediated wind pollination has been proposed for one species whereby minute thrips and beetles mobilize pollen that is subsequently carried to the female flowers by wind.

The interaction between palms and their visiting fauna represents a trade-off between the services provided by the potential pollinators and the antagonistic acitivities of non-pollinating insect visitors. The specificity of the insect pollinators varies. Some groups such as the bees are opportunists whereas some weevils depend completely on one palm species to complete their life cycle. It has also been shown that the composition of the insect fauna visiting palm inflorescences varies through space and time. The broad pollination syndromes outlined by Henderson (1986), which provided extrememely useful concepts in the initial stages of exploration of pollination mechanisms in palms, are probably too simplistic to realistically reflect the rich variation in reproductive traits and biological interactions found in palm pollination systems.

Comparative studies of palm–pollinator interactions in closely related palm species with contrasting pollination mechanisms have revealed transitions in floral morphology, phenology and anatomy that can be associated with shifts in pollination vectors. Data scarcity, sample bias and the complexity of palm–pollinator interactions render the interpretation of these results within a broader phylogenetic framework difficult. Nevertheless, such studies show promise for gaining further insights into the evolutionary aspects of palm pollination. In addition, a number of synecological studies of palms as a component of larger anatagonistic and mutualistic networks have recently appeared. They have shown that asynchronous flowering and partitioning of pollinator guilds could be important mechanisms for limiting gene flow between closely related sympatric taxa and therefore potential drivers of speciation processes. They also provide valuable insight into the ability of palms to attract pollinators in competion with other flowering plants and show how assemblies of insects in tropical forests may influence the reproductive success of palms.

An important priority should be to remedy the geographical and taxonomic bias found in existing palm pollination studies towards South America and the tribes Cocoseae and Phytelepheae. The acquisition of data on phylogenetic structure, population genetics and the synecology of palm communities should also be prioritized so as to gain a better insight into the complex role of pollination mechanisms in the evolution and diversification of palms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research (272-06-0476) and the Carlsberg Foundation (2010-01-0345). We are grateful to our colleagues for fruitful discussions on subjects relevant to this paper, particularly Andrew Henderson, Henrik Balslev, Rodrigo Bernal, Bill Baker, John Dransfield, Sophie Nadot and Fred Stauffer. We thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments to the manuscript.

Pollination studies conducted on palms broken down into subfamilies and tribes.

| Calamoideae (21) | |

| Eugeisonneae (1) | Eugeissona tristis Griff. (Wiens et al., 2008). |

| Lepidocaryeae (7) | Mauritia flexuosa L. f. (Ervik, 1993; Storti, 1993). |

| Calameae (13) | Calamus bousigonii Becc., C. longisetus Griff., C. perigrinus Furtado, C. radicalis H. Wendl. and Drude (Kitching et al., 2007); C. rudentum Lour. (Bøgh, 1996); Salacca zalacca (Gaertn.) Voss (Mogea, 1978 [as S. edulis Reinw.]). |

| Nypoideae (1) | |

| Nypa fruticans Wurmb (Essig, 1973; Fong, 1987; Hoppe, 2005). | |

| Coryphoideae (46) | |

| Sabaleae (1) | Sabal etonia Swingle ex Nash (Zona, 1987); S. palmetto (Walter) Lodd. ex Schult. and Schult. f. (Brown, 1976). |

| Cryosophileae (10) | Cocothrinax argentata (Jacq.) L.H. Bailey (Khorsand Rosa and Koptur, 2009); Cryosophila williamsii P. H. Allen (Henderson, 1984 [as C. albida Bartlett]); Thrinax parviflora Sw. (Read, 1975). |

| Phoeniceae (1) | Phoenix canariensis Chabaud (Meekijjaroenroj and Anstett, 2003); P. dactylifera L. (Dowson, 1962). |

| Trachycarpeae (18) | Chamaerops humilis L. (Herrera, 1989; Anstett, 1999; Caissard et al., 2004; Dufay et al., 2004; Dufay, 2010); Licuala distans Ridl., L. spinosa Wurmb (Barfod et al., 2003); L. peltata Roxb. ex Buch.-Ham. (Barfod et al., 2003; Stauffer et al., 2009); L. ramsayi (F. Muell.) Domin (Kitching et al., 2007); Rhapidophyllum hystrix (Frazer ex Thouin) H. Wendl. and Drude (Shuey and Wunderlin, 1977); Serenoa repens (W. Bartram) Small (Carrington et al., 2003). |

| Chuniophoniceae (4) | no studies. |

| Caryoteae (3) | Arenga obtusifolia Mart.; A westerhoutii Griff. (Zakaria et al., 2000). |

| Corypheae (1) | no studies. |

| Borasseae (8) | Borassus aethiopum Mart. (Thione, 2000). |

| Ceroxyloideae (8) | |

| Cyclospatheae (1) | no studies. |

| Ceroxyleae (4) | Ceroxylon quindiuense (Karst.) H. Wendl. (Kirejtshuk and Couturier, 2009). |

| Phytelepheae (3) | Aphandra natalia (Balslev and A. Hend.) Barfod (Ervik, 1993; Ervik et al., 1999); Phytelephas aequatorialis (Ervik et al., 1999); P. seemannii O.F. Cook (Bernal and Ervik, 1996); P. tenuicaulis (Barfod) A. Hend. (Barfod et al., 1987 [as P. microcarpa Ruiz and Pav. subsp. tenuicaulis Barfod]) |

| Arecoideae (107) | |

| Iriarteae (5) | Iriartea deltoidea Ruiz and Pav. (Henderson, 1985 [as I. ventricosa Mart.]; Bullock, 1981 [as I. gigantea H. Wendl.], van Dulmen, 2001); Socratea durissima (Bullock, 1981); S. exorrhiza (Mart.) H. Wendl. (Henderson, 1985); Wettinia quinaria (O.F. Cook and Doyle) Burret (Núñez-Avellaneda et al., 2005). |

| Chamaedoreae (5) | Chamaedorea alternans H. Wendl. in E. Von Regel (Otero-Arnaiz and Oyama, 2001); C. ernestii-augustii H. Wendl. (Morgan, 2007); C. neurochlamys Burret (Morgan, 2007); C. oblongata Mart. (Morgan, 2007); C. pinnatifrons (Jacq.) Oerst. (Listabarth, 1992); C. radicalis Mart. (Berry and Gorchov, 2004); C. tepejilote Lieb. in Mart. (Oyama and Mendoza, 1990; Morgan, 2007); Wendlandiella gracilis Dammer (Listabarth, 1992 [as W. sp.]) |

| Podococceae (1) | no studies |

| Oranieae (1) | no studies |

| Sclerospermeae (1) | no studies |

| Roystoneae (1) | no studies |

| Reinhardtieae (1) | no studies |

| Cocoseae (18) | Acrocomia aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. (Scariot et al., 1991; Listabarth, 1992); Aiphanes chiribogensis Borchs. and Balslev; A. eggersii Burret (Borchsenius, 1993); A. erinacea (H. Karst.) H. Wendl. in O.C.E. Kerchove de Denterghem; Astrocaryum aculeatum G. Mey. (van Dulmen, 2001); A. alatum Loomis (Bullock, 1981); A. acaule Mart., A. gynacanthum Mart. (Silberbauer-Gottsberger et al., 2001); A. gratum F. Kahn and B. Millan (Listabarth, 1992); A. mexicanum Liebm. ex Mart. (Búrquez et al., 1987; Aguirre and Dirzo, 2008); A. vulgare (Consiglio and Bourne, 2001; Oliveira et al., 2003; Padilha et al., 2003); Attalea allenii H.E. Moore (Núñez-Avellaneda et al., 2005); A. attaleoides (Barb. Rodr.) Wess. Boer; A. funifera (Voeks, 1988, 2002); A. microcarpa Mart. (Silberbauer-Gottsberger et al., 2001); A. maripa (Aubl.) Mart. (Storti and Filho, 1993); A. phalerata Mart. ex Spreng. (Anderson et al., 1988 [as Orbignya phalerata]; Marques et al., 2009); A. speciosa Mart. (Anderson, 1983 [as Orbignya martiana Barb. Rodr.]); Bactris coloradonis L.H. Bailey (Beach, 1984 [as B. porschiana Burret]); B. gasipaes C.S. Kunth in F.W.H.A. von Humboldt, A.J.A Bonpland and C.S. Kunth (Mora Urpí and Solis, 1980; Beach, 1984); B. guineensis (L.) H.E. Moore; B. major Jacq. (Essig, 1971); B. hirta Mart. (Silberbauer-Gottsberger et al., 2001); B. hondurensis Standl. (Bullock, 1981 [as B. wendlandiana Burret]); B. longiseta H. Wendl. ex Burret (Bullock, 1981); B. cf. simplicifrons Mart. (Listabarth, 1992 [as B. cf. mitis]); Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. (Silberbauer-Gottsberger, 1973 [as Butia leiospatha (Barb. Rodr.) Becc.]); Cocos nucifera L. (Lepesme, 1947; Scholdt and Mitchell, 1967; Ohler, 1984; Cock, 1985; da Conceiçao et al., 2004, 2009; Fernández-Barrera and Zizumbo-Villareal, 2004; Meléndez-Ramírez et al., 2004); Desmoncus polyacanthos Mart. (Listabarth, 1994; van Dulmen, 2001); D. sp. (Listabarth, 1992); Elaeis guineensis Jacq. (Syed, 1979; Greathead, 1983; Dhileepan, 1992, and others). |

| Manicarieae (1) | no studies |

| Euterpeae (5) – | Euterpe precatoria Mart. in A.D. d'Orbigny (Küchmeister et al., 1997; van Dulmen, 2001; Velarde and Moraes, 2008); Hyospathe elegans Mart. (Listabarth, 2001). Oenocarpus bacaba Mart. (Silberbauer-Gottsberger et al., 2001); O. bataua (Nuñez-Avellanda and Rojas-Robles, 2008); P. acuminata var. acuminata (Bannister, 1970 [as Euterpe globosa Gaertn.]; P. decurrens (H. Wendl. ex Burret) H.E. Moore (Bullock, 1981; Ervik and Bernal, 1996); P. schultzeana (Ervik and Feil, 1997) |

| Geonomateae (6) | Asterogyne martiana (H. Wendl.) H. Wendl. ex Drude (Schmid, 1970a, b); Calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (Linden and H. Wendl.) H. Wendl. (Cunningham, 2000; Tschapka, 2003; Tschapka and Cunningham, 2004; Sperr et al., 2009); Geonoma cuneata H. Wendl. ex Spruce var. sodiroi (Dammer ex Burret) Skov; G. irena Borchs (Borchsenius, 1997); G. epetiolata (Martén and Quesada, 2001); G. macrostachys Mart. (Olesen and Balslev, 1990; Knudsen, 2002); Welfia regia H. Wendl. (Bullock, 1981 [as Welfia georgii H. Wendl.]) |

| Leopoldinieae (1) | no studies |

| Pelagodoxeae (2) | no studies |

| Areceae (59) | Archontophoenix cunninghamiana (H. Wendl.) H. Wendl. and Drude (Skutch, 1932); Howea belmoreana (C. Moore and F. Muell.) Becc. H. forsteriana (C. Moore and F. Muell.) Becc. (Savolainen et al., 2006); Ptychosperma macarthurii (H. Wendl. ex H.J. Veitch) H. Wendl. ex Hook. f. (Essig, 1973); Normanbya normanbyi (F. Muell.) L.H. Bailey (Kitching et al., 2007); Hydriastele microspadix (Warb. ex K. Schum. and Lauterb.) Burret (Essig, 1973). |

The number of genera according to Dransfield et al. (2008) is given in parentheses. Species are listed alphabetically. Author names are according to Govaerts and Dransfield (2005) (only studies with a main focus on pollination mechanisms are included).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aguirre A, Dirzo R. Effects of fragmentation on pollinator abundance and fruit set of an abundant understory palm in a Mexican tropical forest. Biological Conservation. 2008;141:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Aizen M, Morales CL, Morales J.M. Invasive mutualists erode native pollination webs. PLoS Biology. 2008;6:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060031. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AB. The biology of Orbignya martiana (Palmae), a tropical dry forest dominant in Brasil. PhD Thesis: University of Florida; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AB, Overal B, Henderson A. Pollination ecology of a forest-dominant palm (Orbignya phalerata Mart.) in Northern Brazil. Biotropica. 1988;20:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Anstett MC. An experimental study of the interaction between the dwarf palm (Chamaerops humilis) and its floral visitor Derelomus chamaeropsis throughout the life cycle of the weevil. Acta Oecologica. 1999;20:551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ashe JS. Major features in the evolution of relationships between gyrophaenine staphylinid beetles (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae: Aleocharinae) and fresh mushrooms. In: Wheeler Q, Blackwell M, editors. Fungus insect relationships; perspectives in ecology and evolution. New York: Columbia University Press; 1984. pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ashe JS. Egg chamber production, egg protection and clutch size among fungivorous beetles of the genus Eumicrota (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) and their evolutionary implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1987;90:255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Askgaard A, Stauffer F, Hodel DR, Barfod AS. Floral structure in the Neotropical palm genus Chamaedorea (Arecoideae, Arecaceae) Anales del Jardin Botanico de Madrid. 2008;65:197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma H, Toyota M, Asakawa Y, Takaso T, Tobe H. Floral scent chemistry of mangrove plants. Journal of Plant Resources. 2002;115:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s102650200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balslev H, Henderson A. The identity of Ynesa colenda (Palmae) Brittonia. 1987;39:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister BA. Ecological life cycle of Euterpe globosa Gaertn. In: Odum HT, Pigeon RF, editors. A tropical rain forest: a study of irradiation and ecology. Oak Ridge, TN: Atomic Energy Commission; 1970. pp. B299–B314. [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS. A monographic study of the subfamily Phytelephantoideae (Arecaceae) Opera Botanica. 1991;105:5–73. [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS, Uhl NW. Floral development in Aphandra natalia (Balslev and Henderson) Barfod (Arecaceae, subfam. Phytelephantoideae) American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS, Henderson A, Balslev H. A note on the pollination of Phytelephas microcarpa (Palmae) Biotropica. 1987;19:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS, Ervik F, Bernal R. Recent evidence on the evolution of phytelephantoid palms (Palmae) Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden. 1999;83:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS, Burholt T, Borchsenius F. Contrasting pollination modes in three species of Licuala (Arecaceae: Coryphoideae) Telopea. 2003;10:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Barfod AS, Trénel P, Borchsenius F. Diversification, timing and character evolution of the vegetable ivory palms (Phytelepheae) In: Seberg O, Barfod AS, Petersen G, Davis J, editors. Proceedings of the fourth International Conference on Comparative Biology of the Monocotyledons. Aarhus: University Press; 2010. pp. 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bascompte J, Jordano P. Plant–animal mutualistic networks: the architecture of biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 2007;38:567–593. [Google Scholar]

- Basri MW. Developments of the oil palm pollinator Elaeidobious kamerunicus in Malaysia. Palm Oil Developments. 1984;2:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Beach JH. The reproductive biology of the peach or ‘Pejibayé’ palm (Bactris gasipaes) and a wild congener (B. porschiana) in the Atlantic lowlands of Costa Rica. Principes. 1984;28:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Begon M, Harper JL, Townsend CR. Ecology. 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal R, Ervik F. Floral biology and pollination of the dioecious palm Phytelephas seemannii in Colombia: an adaptation to staphylinid beetles. Biotropica. 1996;28:682–696. [Google Scholar]

- Berry EJ, Gorchov DI. Reproductive biology of the dioecious understorey palm Chamaedorea radicalis in a Mexican cloud forest. Pollination vector, flowering phenology and female fecundity. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2004;20:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Bøgh A. The reproductive phenology and pollination ecology of four Calamus (Arecaceae) species in Thailand. Principes. 1996;40:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius F. Flowering biology and insect visitation of three Ecuadorean Aiphanes species. Principes. 1993;37:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius F. Flowering biology of Geonoma irena and G. cuneata var. sodiroi (Arecaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1997;208:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius F. Staggered flowering in four sympatric varieties of Geonoma cuneata (Palmae) Biotropica. 2002;34:603–606. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KE. Ecological studies of the cabbage palm, Sabal palmetto. Principes. 1976;20:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SH. Notes on the phenology of inflorescences and pollination of some rain forest palms in Costa Rica. Principes. 1981;25:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Búrquez A, Jose Sarukhán K, Pedroza AL. Floral biology of a primary rain forest palm, Astrocaryum mexicanum Liebm. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1987;94:407–419. [Google Scholar]

- Caissard JC, Meekijjironenroj A, Baudino S, Anstett MC. Localization of production and emission of pollinator attractant on whole leaves of Chamaerops humilis (Arecaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2004;91:1190–1199. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.8.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington ME, Gottfried TD, Mullahey JJ. Pollination biology of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) in Southwestern Florida. Palms. 2003;47:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cock MJ. Does a weevil pollinate coconut palm? Curculio. 1985;18:8. [Google Scholar]

- da Conceição ES, Delabie JHC, Costa Neto AO. The entomophily of the coconut tree in question: the evaluation of pollen transportation by ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) in inflorescence. Neotropical Entomology. 2004;33:679–683. [Google Scholar]

- da Conceição ES, Delabie JHC, Costa Neto AO, et al. Actividad de formigas nas inflorescências do coqueiro no sudeste baiano, com enfoque sobre o período entre antese e a formação do fruta. Agrotrópica. 2009;21:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio TK, Bourne GR. Pollination and breeding system of a Neotropical palm Astrocaryum vulgare in Guyana: a test of the predictability of syndromes. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2001;17:577–592. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham SA. Ecological constraints on fruit initiation by Calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (Arecaceae): floral herbivory, pollen availability and visitation by pollinating bats. American Journal of Botany. 1995;82:1527–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham SA. What determines the number of seeds produced in a flowering event? A case study of Calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (Arecaceae) Australian Journal of Botany. 2000;48:659–665. [Google Scholar]

- De Steven D. Vegetative and reprodutive phenologies of a palm assemblage in Panama. Biotropica. 1987;19:342–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dhileepan K. Pollen carrying capacity, pollen load and pollen transferring ability of the oil palm pollinating weevil Elaeidobius kamerunicus Faust in India. Oléagineux. 1992;47:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JMI, McGovern TP, Ladd TL. Floral attractants for Cetoniinae and Rutelinae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Journal of Economic Entomology. 1990;83:1298–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Dowe JL. A taxonomic account of Livistona R. Br. (Arecaceae) The Garden's Bulletin Singapore. 2009;60:185–344. [Google Scholar]

- Dowson VHW. A note on the pollination of date palms. Principes. 1962;6:139. [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield J, Uhl NW, Asmussen CB, Baker WJ, Harley MM, Lewis CE. Genera Palmarum, the evolution and classification of palms. Kew: Kew Publishing, Royal Botanic Gardens; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dufay M. Impact of plant flowering phenology on the cost/benefit balance in a nursery pollination mutualism, with honest males and cheating females. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2010;23:977–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufay M, Hossaert-McKey M, Anstett MC. Temporal and sexual variation of leaf-produced pollinator-attracting odours in the dwarf palm. Oecologia. 2004;139:392–398. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen A. Pollination and phenology of flowers in the canopy of two contrasting rain forest types in Amazonia, Colombia. Plant Ecology. 2001;153:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik F. Pollination of the dioecious palms Mauritia flexuosa, Aphandra natalia, Phytelephas aequatorialis and Phytelephas macrocarpa in Ecuador. MSc Thesis, University of Aarhus: Denmark; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik F, Bernal R. Floral biology and insect visitation of the monoecious palm Prestoea decurrens on the Pacific coast of Colombia. Principes. 1996;40:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik F, Barfod AS. Thermogenesis in palm inflorescences and its ecological significance. Acta Botanica Venezuelica. 1999;22:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik F, Feil P. Reproductive biology of the monoecious understory palm Prestoea schultzeana in Amazonian Ecuador. Biotropica. 1997;29:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Ervik F, Tollsten L, Knudsen JT. Floral scent chemistry and pollination ecology in phytelephantoid palms. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1999;217:279–297. [Google Scholar]

- Essig FB. Observations on pollination in Bactris. Principes. 1971;15:20–24. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Essig FB. Pollination of some New Guinea palms. Principes. 1973;17:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Evans TD, Sengdala K, Viengkham OV, Thammavong B. A field guide to the Rattans of Lao PDR. Kew: The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Feil JP. Reproductive ecology of dioecious Siparuna (Monimiaceae) in Ecuador – a case of gall midge pollination. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1992;110:171–203. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Barrera M, Zizumbo-Villareal D. Mixed mating strategies and pollination by insects and wind in coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L. (Arecaceae)): importance in production and selection. Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 2004;6:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Flach M. Sago palm Metroxylon sagu Rottb. Rome: International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI); 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fong FW. Insect visitors to the Nipa inflorescence in Kuala Selangor. Natura Malaysiana. 1987;12:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano G, Bernal R. Palmas de Colombia, guía de campo. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- García SM. Observaciones de polinización en Jessenia bataua (Arecaceae). 1988 MSc Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Ecuador. [Google Scholar]

- Govaerts R, Dransfield J. World checklist of palms. Kew: The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greathead DJ. The multi-million dollar weevil that pollinates oil palms. Antenna. 1983;7:105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hegland SJ, Nielsen A, Lazaro A, Bjerknes AL, Totland O. How does climate warming affect plant–pollinator interactions? Ecology Letters. 2009;12:184–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. Observations on pollination of Cryosophila albida. Principes. 1984;28:120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. Pollination of Socratea exorrhiza and Iriartea ventricosa (Palmae) Principes. 1985;29:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. A review of pollination studies in the Palmae. The Botanical Review. 1986;52:221–259. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. Evolution and ecology of palms. New York: New York Botanical Garden Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A, Rodrígues D. Raphides in palm anthers. Acta Botanica Venezuelica. 1999;22:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A, Fischer B, Scariot A, Pacheco MAW, Pardini R. Flowering phenology of a palm community in a central Amazon forest. Brittonia. 2000a;52:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A, Pardini R, Rebello JFD, Vanin S, Almeida D. Pollination of Bactris (Palmae) in an Amazon forest. Brittonia. 2000b;52:160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera J. On the reproductive biology of the dwarf Palm, Chamaerops humilis in southern Spain. Principes. 1989;33:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel DR. Chamaedorea palms: the species and their cultivation. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe LE. The pollination biology and biogeography of the mangrove palm Nypa fruticans Wurmb (Arecaceae) MSc Thesis, wAarhus University: Denmark; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Howard FW, Moore D, Giblin-Davis RM, Abad RG. Insects on palms. Wallingford: CABI; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Khorsand Rosa R, Koptur S. Preliminary observations and analyses of pollination in Coccothrinax argentata: Do insects play a role? Palms. 2009;53:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel TM, do Nascimento LM, Piechowski D, Sampaio EVSB, Nogueira Rodal MJ, Gottsberger G. Pollination and seed dispersal modes of woody species of 12-year-old secondary forest in the Atlantic Forest region of Pernambuco, NE Brazil. Flora. 2010;205:540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Kirejtshuk GA, Couturier G. Species of Mystropini (Coleoptera, Nitidulidae) associated with inflorescences of palm Ceroxylon quindiuense (Karst.) H. Wendl. (Arecaceae) from Peru. Japanese Journal of Systematic Entomology. 2009;15:57–77. [Google Scholar]