Adriana's Story

Meet Adriana. She's 17, lives with her parents, and, like about 1 in 6 teen girls in the U.S., she has a child. My research team got to know Adriana and 75 other teen parents through in-depth interviews in the Denver area in 2008-2009. A Latina high school student who looks and acts older than her age, Adriana has a two-year-old son, Marlon. Like the overwhelming majority of teen mothers, Adriana didn't intend to get pregnant: “I would always play with my little baby dolls and stuff, but I wasn't really thinking about, ‘Oh, when am I gonna be a mom?’ I didn't really care about that stuff. And then actually, to tell you the truth, when I got pregnant, I wasn't really thinking about being a mom yet, either. It just kind of happened.”

Similarly, Adriana's boyfriend Michael was like many other young dads: “happy,” even “over-excited,” about becoming a father. But Adriana said, “Once I found out I was pregnant, I didn't want him to be my boyfriend.” Still, he moved in with her family. Later, they lived with Michael's family. In contrast to stereotypes about uninvolved young fathers, it's very common for teen births to occur in the context of a long-term romantic relationship and for the child's father to live with the mom. However, these teen relationships frequently dissolve. Michael and Adriana were together for three years: “… after I had my son … I told him it was either my own place or I was leaving him. So he got me my own place. We lived there for about a year and a half, and then, like, we would fight all the time. … We just realized that we were unhappy together. And last year we just broke up. It's been kind of hard on the baby.” She says the breakup is “also a reason, kind of, why I feel awkward about getting pregnant so young, because I didn't really know what love was. I think it would be better if my son had his mom and his dad there together in a relationship, growing up with both parents involved daily. And I think that if I would have waited longer, I would have knew a little more, been a little wiser about who to have a baby with.” Marlon saw his father infrequently right after the breakup, but now it's just on weekends at Michael's mother's house.

Marlon now lives with Adriana, her father and stepmother, grandmother, and several siblings. Adriana's father (a fast food worker) and grandmother pay for housing and other bills. Michael provides limited help, but as is typical for teen moms who don't live with their child's father, Adriana is responsible for keeping track of her son's needs and asking Michael for support. Michael's mother helps by providing child care. Medicaid pays Adriana's medical bills, and the WIC program helped her with buying formula. This reliance on a network of extended family members for considerable support, supplemented by health care and nutritional support from the government (but not by welfare payments), is common. Despite this assistance, Adriana is still in a precarious financial situation. She doesn't often have spending money, because “as long as I don't need something really bad, I don't want to ask for it.” Adriana worries about straining her family's resources.

In America, teen parenthood is commonplace but polarized—and polarizing.

While Adriana's story is certainly personal, it is far from unique. About 1 in 3 girls in the U.S. becomes pregnant before turning 20. About a third of these pregnancies end in abortion, but the majority of the rest become parents. (American girls ages 15-19 are about 3 times as likely as their Canadian peers to have a child, 7 times as likely as Swedes, and almost 9 times as likely as Japanese teens.) Adriana's experience exemplifies many of the larger social realities shaping teen parenthood today. These include historical changes in the typical American life course, shifting attitudes about the “problem” of teen pregnancy, social inequality and the polarized experience of teen parenthood in the U.S., and the many social consequences teen parents face for being “kids having kids.”

Who Are The Kids Who Have Kids?

Parenting is not evenly distributed among American teenagers. In fact, we might say that teen parenthood is an extremely polarized experience—common in some segments of the population and rare in others.

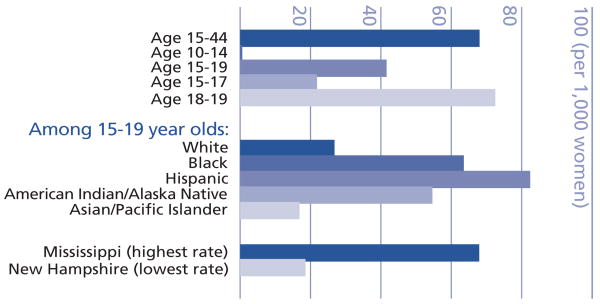

Teen mothers and fathers overwhelmingly come from lower-income families and neighborhoods, and they are often struggling in school even before the pregnancy. A national study of babies born in 2001 revealed that about half of teen mothers' children live in poverty, and more than half of all children living in poverty have a mother who was once a teenage parent. Teen parenting also varies by race and ethnicity, with Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans having the highest rates (see chart on p. 35). On the other hand, teen parenthood is relatively rare in high socioeconomic status, Asian American, and white families and neighborhoods.

There's little doubt that contraception (or lack thereof) is an important part of this package. While American teenagers start having sex at similar ages to their peers in many other Western countries, they are much more likely to get pregnant and have children, even though the vast majority of teen pregnancies are unintended. Many researchers attribute this difference to American teens' less consistent contraception patterns.

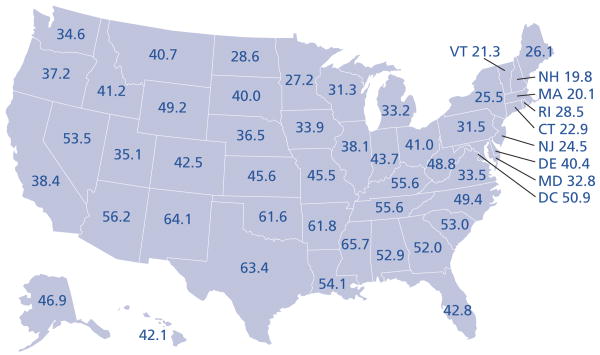

Geography is another intriguing dimension of variation in teen parenthood. White teens in parts of the Southeast are more likely to get pregnant than elsewhere, as are Latina and African American teens in this region. Perhaps counterintuitively, states with high levels of conservative religious affiliations have some of the highest teen birthrates (see map below), and many Evangelical young people are at risk of becoming teen parents.

My recent interviews with college students showed that particularly in low socioeconomic status, conservative religious communities, a negative view of teen parenting is balanced against a “pro-life” social norm that encourages teens not to have an abortion. Teens are told that having the child is the “lesser of two evils.” This echoes the Palin family's reaction to daughter Bristol's unwed teen pregnancy, and some of our participants told us it was a recent opinion shift in their communities. In most of the study's higher socioeconomic status, less religious communities, there's no cautiously positive take on teen parenting. Parents actively encourage their children to delay sex, but believe that if they do have sex, they should contracept consistently. Teens who “mess up” by getting themselves or a partner pregnant are not judged as immoral, but as “stupid.”

Problematic Perceptions

For many, teen parenthood symbolizes “what's wrong” with America today. Media outlets breathlessly report the details of celebrity pregnancies and create reality shows about teen mothers, then air call-in sessions about the irresponsibility of young people. This simultaneous attention and condemnation is shared by the general public. In a 2004 opinion poll, teen pregnancy was rated by 42 percent as a “very serious problem” in our society, and another 37 percent considered it to be an “important problem.”

Why is such a commonplace event viewed so negatively? The fact that teenage pregnancy disproportionately impacts racial minorities and low-income communities is key. Such patterns play into mainstream fears about social disorder and excessive reliance on social services and the welfare state. There is a persistent, racialized public stereotype of the black or Latina “welfare queen” (even though the vast majority of teenage mothers do not receive welfare benefits).

This interpretation is somewhat confirmed by the fact that the general public's attitudes about teen childbearing are divided along racial lines, too. In a 2005 survey of American adults, for example, I asked people how embarrassed they would be by a hypothetical unwed teen pregnancy in their household. African Americans reported less embarrassment than other racial groups, and people who had attended college reported more embarrassment than those with less education.

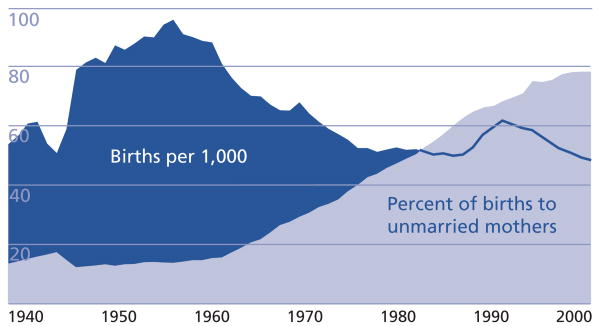

Some historical perspective is important here as well. The U.S. has a long history of teen childbearing. Looking at the teen birthrate since the start of the Second World War (see above), the high point for teen births was in the mid-1950s. Yet teen parenthood did not fully emerge as an important “social problem” until the 1970s. The explanation probably lies in the marital context of teen births.

Back in the 1950s, it was common and socially acceptable for people to get married and immediately become parents in their late teens or early twenties. Technically, this made lots of young people teen parents, but it wasn't considered a problem because they were engaging in a “normal” life course. In contrast, nonmarital births were rare and stigmatized.

Since then, the experience of early adulthood has changed. Many young people now enjoy a longer period of independence before settling into to adult roles, and most Americans delay marriage until at least their mid-twenties. At the same time, most have sex before their twentieth birthday, putting them at risk for unintended pregnancy. As it has for all births (4 in 10 births in the U.S. are now nonmarital, compared to 4 in 100 in 1950), the proportion of teen births that are nonmarital has risen dramatically over time: 87 percent of teen births were nonmarital in 2008. Sociologist Frank Furstenberg has pointed out that, as nonmarital teen births increased, so did the visibility of teen parenting as a social problem.

These social attitudes and community norms clearly impact young people. In my analysis of a national survey of teenagers in 1995, most teens said they would feel embarrassed if they got (or for boys, got a girl) pregnant. This contradicts the popular idea that teens today think pregnancy is “cool.”

Adriana's story illustrates how family and community reactions can shape teen parents' lives. Some of her family members reacted fairly well to her pregnancy, but others did not. Adriana's intelligence and morality were questioned. “My mom was just like, she didn't get mad. She just kind of said that my boyfriend has to take responsibility, ‘cause he's the one who got me pregnant. So she kind of was like, ‘Oh, well, I guess you're moving in tomorrow and you're gonna pay this bill and this bill and this bill… You're not taking my daughter out of the house.’ ” Adriana's brother called her “stupid” and wanted “to beat my boyfriend up.” But “the only one who really made me feel bad was my grandma,” who told her that it was “wrong” for her to get pregnant so young. Adriana said, “I was really close to her. So I took it kind of hard. …We really don't talk any more. She talks to my son more than to me.”

Media outlets' simultaneous attention to and condemnation of teen pregnancies are shared by the public.

Adriana also feels socially ostracized. She says, “I really don't have lots of friends.” This social isolation is typical and differs sharply from the common stereotype of teen girls encouraging their friends to get pregnant or forming “pregnancy pacts.” Out in public, she attracts negative attention: “Sometimes I would be on the bus and people would just stare at me… [At] prenatal appointments, people were like, ‘How old are you? What are you gonna do with a kid this young?’ Stuff like that… It looks kind of bad to see a really young girl pregnant, but also, they don't know me, what I do.” She's learning to cope, she says. “Now when I look at people, I'm like, ‘Whatever. You don't even know me.’ …I'm like, ‘I still go to school.’ I can throw that in their face… I have something that would possibly hold me back, and I still do it.” Like many other teen moms, Adriana has been forced to learn coping skills to negotiate public stigma. Proving skeptical people wrong is one reason why many teen parents told us they wanted to succeed in school.

Consequences

The consequences of teen parenthood, for young parents and their children alike, are complicated. For decades, researchers have documented negative outcomes for teen mothers in terms of education, income, mental health, marriage, and more. Teen fathers have lower levels of education and employment than their peers, and, compared to other kids, children of teen parents have compromised development and health starting in early childhood and continuing into adolescence.

In research explaining these consequences, two surprising findings have emerged. First, by comparing teen mothers to natural comparison groups such as their childless twins and sisters and pregnant teens who miscarried, scholars like public health researcher Arline Geronimus and economist V. Joseph Hotz have shown that most of the negative “consequences” of teen childbearing are actually due to experiences in teens' lives from before they got pregnant, such as socioeconomic background and educational achievement. In other words, the experience of teen childbearing itself only moderately worsens these teens' life outcomes.

Second, the negative consequences of teen parenthood are more severe in the short term. In the long term, many teen parents end up with better outcomes than it looked like they would have when they were teens. For example, developmental psychologist Julie Lounds Taylor found in a predominantly white, socioeconomically advantaged sample of 1957 Wisconsin high school graduates that at midlife, former teenage mothers and fathers lagged behind peers with similar characteristics in terms of education, occupational status, marital stability, and physical health. On the other hand, their work involvement, income levels, satisfaction with work and marriage, mental health, and social support were similar. Using more recent data from a national longitudinal study of eighth graders from 1988, I found that 75 percent of teen mothers and 62 percent of fathers finished a high school degree or GED by age 26. However, compared to the typical American, their outcomes were still problematic: both teen moms and dads ended up with two years less education than average by age 26.

Adriana's story is again illustrative. She wasn't on a traditional path to academic success before she got pregnant. As a Latina from a family with low socioeconomic status, she already belonged to a high-risk group, and her academic experiences reflected it. Adriana says, “Before I was a mom, I didn't really go to school. I didn't like school.” But once she got pregnant, she thought, “ ‘What am I gonna give my son?’ …He's gonna have the same life that I had, and then he can follow in my footsteps, and I don't want that. I want him to do some things…” She started attending a school for pregnant teen girls. “Ever since then… I've passed all my classes, and now I graduate in December.” There are supportive teachers and understanding fellow students. Infant care and other forms of support are available. Adriana now plans to enroll in postsecondary education.

The support context of teen parenthood varies widely. For example, there are racial and ethnic differences in the key people helping teen mothers. My analysis of a national sample of babies born in 2001 found that about 60 percent of Latina and white teen moms were living with their child's father nine months after the birth, compared to just 16 percent of black teen moms. Instead, nearly 60 percent of black teen moms were living with other adults, such as a parent. It's not clear which of these situations is most beneficial for teen moms and their children: although as a society we often wish for fathers to be more involved, teen relationships often break up, and instability in mothers' relationships can compromise children's development.

Effective Social Supports

American teen parenthood is commonplace but polarizing. As our societal safety net shrinks, low-income families' prospects worsen, and education becomes increasingly important for financial success, teen parents face increasingly long odds. Adriana's story helps show how many teen parents are motivated to work hard and make a better life for themselves and their children. Our country has made an important commitment to reducing levels of teen pregnancy, but we also need to find better ways to support teens who are already parents so their families can have a better future.

The federal government has now committed substantial funding for both prevention of teen pregnancies and support for teens who are already parents. Supporting parenting teens is a smart societal investment. First, because most mothers of children living in poverty today were teen moms, targeting these families for intervention would be an effective way to help some of the most marginalized members of our society. This is true regardless of whether the negative outcomes were caused by teen parenthood itself or by factors related to the teen's situation before the pregnancy.

Second, with less financial support available from the government, especially since welfare reform was passed in 1996, teen parents and their children are more dependent on their families for survival. Many low-income families have less money and time than they did in the past, making it harder for them to support teen parents and their children. Research finds that families still provide substantial support, but it often severely strains their budgets and their relationships with the young parents, and many teens' and children's basic needs such as for food and warm clothing are not being met. The current economic crisis has exacerbated this situation.

Finally, as many service providers have long known, the time after a teen birth is a magic moment when societal investments can help nudge young families onto a successful trajectory. Unlike many older parents who can take time out from the labor force and still have attractive options when they re-enter, teens are in a life stage when it is critical for them to invest in education and work. And almost all the teen parents we interviewed were willing to sacrifice to meet their goals. A strong motivation to achieve for their children's sake was common.

Without support from social programs, though, this motivation may not be enough. For example, though Adriana is fully committed to her education and has her family behind her, she has to surmount massive obstacles like transportation and childcare to stay in school. Talking to teen parents like her, it's easy to see how much some short-term support would pay off for her, her son, and our society in the long term.

Supporting parenting teens is a smart societal investment.

Teen birth rates (per 1,000 ages 15-19) by state, 2008.

For many Americans, Bristol Palin is the “face” of teen pregnancy, but her background is not representative of most teen parents.

Births and marital context, women ages 15-19.

Source: Stephanie Ventura (2001). “Births to Teenagers in the United States.” Nonmarital birth data before 1951 not available every year; interpolated by author.

U.S. birth rates by age, race, and location, 2006.

Source: National Vital Statistics Report Vol. 57, No. 7 (2009).

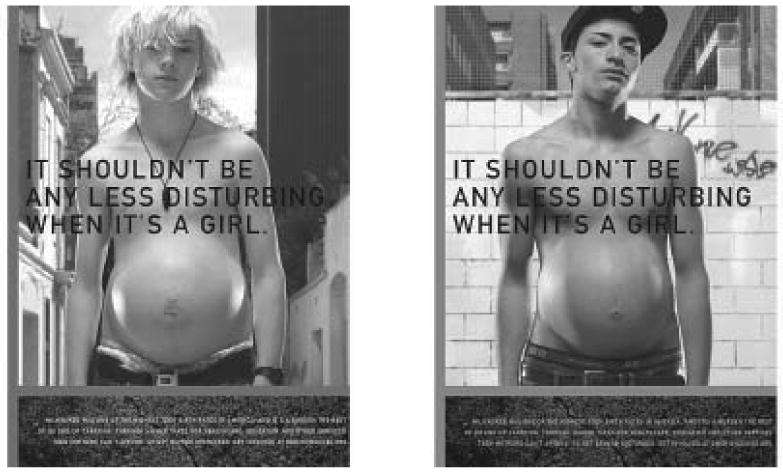

An attention-grabbing public service campaign co-sponsored by the United Way and OneMilwaukee framed teen pregnancy as “disturbing” and a “burden” on taxpayers.

Biography

Stefanie Mollborn is in the sociology department and the Institute of Behavioral Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She studies teen parenting and early childhood.

Footnotes

Names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect anonymity.

Recommended Readings

- Burton Linda M. Teenage Childbearing as an Alternative Life-Course Strategy in Multigeneration Black Families. Human Nature. 1990;1:123–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02692149. Argues, provocatively, that teen motherhood is a rational strategy for girls in very disadvantaged contexts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. University of California Press; 2005. An influential ethnographic exploration of why a majority of women in some low-income communities have children outside marriage. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F., Jr Teenage Childbearing as a Public Issue and Private Concern. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:23–29. An authoritative overview of teen parenthood in the past several decades. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan Elaine Bell. Not Our Kind of Girl: Unraveling the Myths of Black Teenage Motherhood. University of California Press; 1997. Shows the complex and often negative reactions to teen parenting through interviews with African American teen mothers and their families. [Google Scholar]

- Luker Kristin. Dubious Conceptions: The Politics of Teenage Pregnancy. Harvard University Press; 1996. Tackles the “social problem” of teen pregnancy and makes the case that it is often a consequence, rather than a cause, of poverty and social disadvantage. [Google Scholar]

- Turley Ruth N López. Are Children of Young Mothers Disadvantaged because of their Mother's Age or Family Background? Child Development. 2003;74(2):465–474. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402010. An exemplary article showing how teen mothers' family backgrounds matter more for understanding their life outcomes (and those of their children) than the fact that they gave birth as teens. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]